Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Review of From Heaven He Came and Sought Her (Michael J. Lynch)

Încărcat de

Michael Lynch0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

193 vizualizări3 paginiThis review summarizes a book titled "From Heaven He Came and Sought Her: Definite Atonement in Historical, Biblical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspective." The reviewer notes that while the book contains many instructive essays on the doctrine of definite atonement, it lacks precision in defining what definite atonement actually means. Specifically, the book ambiguously defines definite atonement in a way that could also include hypothetical universalism. The reviewer argues the book would have benefited from a clearer understanding that definite atonement is specifically about Christ accomplishing redemption only for the elect, not just applying it to the elect. Overall, the reviewer finds the book a welcome contribution but not as precise or cog

Descriere originală:

Published in the Calvin Theological Journal

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis review summarizes a book titled "From Heaven He Came and Sought Her: Definite Atonement in Historical, Biblical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspective." The reviewer notes that while the book contains many instructive essays on the doctrine of definite atonement, it lacks precision in defining what definite atonement actually means. Specifically, the book ambiguously defines definite atonement in a way that could also include hypothetical universalism. The reviewer argues the book would have benefited from a clearer understanding that definite atonement is specifically about Christ accomplishing redemption only for the elect, not just applying it to the elect. Overall, the reviewer finds the book a welcome contribution but not as precise or cog

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

193 vizualizări3 paginiReview of From Heaven He Came and Sought Her (Michael J. Lynch)

Încărcat de

Michael LynchThis review summarizes a book titled "From Heaven He Came and Sought Her: Definite Atonement in Historical, Biblical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspective." The reviewer notes that while the book contains many instructive essays on the doctrine of definite atonement, it lacks precision in defining what definite atonement actually means. Specifically, the book ambiguously defines definite atonement in a way that could also include hypothetical universalism. The reviewer argues the book would have benefited from a clearer understanding that definite atonement is specifically about Christ accomplishing redemption only for the elect, not just applying it to the elect. Overall, the reviewer finds the book a welcome contribution but not as precise or cog

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 3

[Published

in the Calvin Theological Journal 49 (2014): 352-354]

From Heaven He Came and Sought Her: Definite Atonement in Historical, Biblical,

Theological, and Pastoral Perspective edited by David Gibson and Jonathan Gibson.

Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2013. Pp.703. $50.00.

The doctrine of definite or limited atonement that Christ made a satisfaction for

the sins of the elect only has been a provocative doctrine eliciting a variety of strong

opinions. This compendium of twenty-three essays on the doctrine of definite atonement

is the first of its kind with respect to both the breadth of essays and level of scholarship.

The volume is divided into four large sections which create a map or web of the

doctrine: (1) Church History; (2) The Bible; (3) Systematic Theology; and (4) Pastoral

Theology. The book offers much to learned ministers.

From Heaven He Came and Sought Her is the most up-to-date defense of definite

atonement taking into account all the recent historical research into the diversity of

Reformed theology in the early modern period. Following the lead of historical

theologians like Richard Muller and Lee Gatiss (who authors a chapter in the book), the

book rightly acknowledges the diversity of Reformed positions vis--vis the extent of

Christs satisfaction. For example, it extends the Reformed label to positions once

regarded as non-confessional, the awkward cousins in the [Reformed] family (43), such

as hypothetical universalism (popularly, albeit inappropriately, called four-point

Calvinism), which teaches that Christ made a satisfaction for each and every persons

sins. Refreshingly, the essay by Donald Macleod exposits the prolific seventeenthcentury Reformed hypothetical universalists John Davenant and Richard Baxter at a

depth not typically found in volumes arguing for definite atonement.

Many essays are instructive and well argued. Carl Truemans essay accurately

delineates the differences between Baxter and Owen on the nature of the atonement as

well as its extent. Similarly, Lee Gatiss brings to light the history surrounding the second

article produced at the Synod of Dort. (However, he wishes to define definite atonement

by means of that article, implying that English hypothetical universalism is a definite

atonement position or at least agreeable with it.) Thomas Schreiners essay displays

careful exegesis and cautious conclusions with respect to various New Testament texts

touching on the atonement. Garry Williamss two essays are groundbreaking insofar as

he is the first one (to my knowledge) to interact with the various Reformed critiques of

the double-payment argument. Finally, the essay by Sinclair Ferguson, while found in

the pastoral section of the book, deals extensively and penetratingly with the rather

atypical arguments against definite atonement offered by John Mcleod Campbell in the

nineteenth century.

Even so, the book contains confusing claims that call into question whether this

book can be recommended as a consistent and accurate defense of definite atonement.

From Heaven He Came and Sought Her lacks sufficient precision over how definite

atonement relates to redemption accomplished in distinction from redemption applied.

The most glaring deficiency of the book is its ambiguity over the definition of

definite atonement. The editors introductory essay begins with a definition which

affirms that Christ achiev[ed] the redemption of the elect alone (33), which I take to

mean that Christ in no way accomplished redemption on behalf of the non-elect. This

definition is consistent with definite atonement as found in Reformed theology since the

sixteenth century. However, this is quickly eclipsed by the use of a definition that is not

[Published in the Calvin Theological Journal 49 (2014): 352-354]

distinct to definite atonement. Generally speaking, the books de facto definition often

amounts to little more than this: God intended or designed to savingly apply the benefits

of the death of Christ to the elect alone. That God designed the death of Christ to be

savingly applied only to the elect is hardly controversial among any confessional

Reformed theologian, whether he or she affirms hypothetical universalism or not.

Instead, the book only obfuscates the real issue that advocates of definite atonement

should be arguing, namely, that Christ made a satisfaction only for the sins of the elect.

Other assertions also undermine the uniqueness of definite atonement over against

competing theological claims like hypothetical universalism. For example, the editors

claim that the Synod of Dort is the classic statement of definite atonement (35). They

then assert that hypothetical universalism is confessionally orthodox. This begs the

question, how can Dort be the classic statement of definite atonement while also

allowing for a hypothetical universalist position? This confusion over what is and is not

definite atonement unfortunately persists not merely in the introductory essay but

throughout the whole.

Further evidence that the book appears to miss the real defining mark of definite

atonement, at least as it is historically understood, can be gleaned from the books use

(46; 402) of Louis Berkhofs status quaestionis in his Systematic Theology. Berkhof

asks: Did the Father in sending Christ, and did Christ coming into the world, to make

atonement for sin, do this with the design or for the purpose of saving only the elect or all

men? That is the question, and that only is the question. Berkhof may be confident in

his assertion, but Richard Baxter (a hypothetical universalist) was equally confident in

affirming that Christs death was designed to save the elect alone (Baxter, Universal

Redemption, 481ff.). Instead, the defining issue wholly, and only, concerns Gods will

with regard to Christs satisfactionwas Christ punished for the sins of the elect only or

all human beings? Definite atonement limits redemption accomplished to the elect alone.

Definite atonement should not be used as shorthand for an intention to apply redemption

to the elect alone, but rather for an intention to accomplish redemption for the elect alone.

Only after clearly grasping the correct status quaestionis, which could and should have

been acquired from people like Francis Turretin or Herman Bavinck, can a reader

appropriately judge whether a particular theologian or biblical text teaches or assumes a

definite atonement.

The essays by David Hogg and Michael Haykin illustrate this need for clarity.

Haykins essay on the ancient church and definite atonement draws many specious

conclusions from various quotations of the Patristics. For instance, Haykin argues on the

basis of Jeromes use of the phrase ransom for many, that the words at least hint that

Jerome saw Christs death to be for a particular group of people (70). Yet, it seems

reasonable, even likely, that the word ransom there does not denote redemption

accomplished, but redemption applied. The confusion over redemption accomplished

and applied is equally probable in the case of Haykins exposition of Clement, Hilary,

Ambrose, and Prosper. Hoggs essay dealing with Peter Lombards sufficient/efficient

formula not only displays the same sorts of problems mentioned above, but also

demonstrates a lack of appreciation for the true original purpose of the Lombardian

formula. Hogg spends an exorbitant amount of time (81-88) discussing the predestined

in Lombards theology, based on a misreading of Raymond Blacketer and Jonathan

Rainbow, without discussing the real heart of the matterthe relationship between the

[Published in the Calvin Theological Journal 49 (2014): 352-354]

sufficiency and efficacy of the satisfaction. Moreover, beginning in the latter sixteenth

and early seventeenth centuries, the Lombardian formula was actually revised or rejected

in order to preclude the idea of an unlimited satisfaction. That significantly calls into

doubt whether Peter Lombards formula clearly admits to a definite atonement reading as

Hogg suggests.

All told, the book does not surpass John Owens classic work The Death of Death

in the Death of Christ in terms of precision or cogency of argument. However, it is a

welcome contribution to current conversations regarding the extent of Christs

satisfaction in atonement theology.

Michael J. Lynch

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Themelios, Volume 34 Issue 1Document155 paginiThemelios, Volume 34 Issue 1thegospelcoalition100% (4)

- The UCC and The IRSDocument14 paginiThe UCC and The IRSjsands51100% (2)

- Scope of Inspection For Ammonia TankDocument3 paginiScope of Inspection For Ammonia TankHamid MansouriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting Jesus Wrong: Giving Up Spiritual Vitamins and Checklist ChristianityDe la EverandGetting Jesus Wrong: Giving Up Spiritual Vitamins and Checklist ChristianityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Murray J Christian BaptismDocument100 paginiMurray J Christian BaptismDaniel Rodrigo CezarÎncă nu există evaluări

- God’s Unfolding Story of Salvation: The Christ-Centered Biblical StorylineDe la EverandGod’s Unfolding Story of Salvation: The Christ-Centered Biblical StorylineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defining The Triune God - ATS 2016Document29 paginiDefining The Triune God - ATS 2016javierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law A Serious Call To A Devout and Holy LifeDocument219 paginiLaw A Serious Call To A Devout and Holy LifeMFD JrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engaging Ecclesiology: Papers from the Edinburgh Dogmatics Conference 2021De la EverandEngaging Ecclesiology: Papers from the Edinburgh Dogmatics Conference 2021Încă nu există evaluări

- 2 KURUVILLA Christocentric Interpretation PDFDocument17 pagini2 KURUVILLA Christocentric Interpretation PDFRonald Cabrera100% (1)

- CORPORATION An Artificial Being Created by Operation of Law Having The Right of SuccessionDocument26 paginiCORPORATION An Artificial Being Created by Operation of Law Having The Right of SuccessionZiad DnetÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Skeptic’s Guide to Arts in the Church: Ruminations on Twenty ReservationsDe la EverandA Skeptic’s Guide to Arts in the Church: Ruminations on Twenty ReservationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- They Looked Up and Saw Jesus Only: Searching Together: Fall/Winter 2018De la EverandThey Looked Up and Saw Jesus Only: Searching Together: Fall/Winter 2018Încă nu există evaluări

- Out of the Depths: A Songwriter's Journey Through The PsalmsDe la EverandOut of the Depths: A Songwriter's Journey Through The PsalmsÎncă nu există evaluări

- All that the Prophets Have Declared: The Appropriation of Scripture in the Emergence of ChristianityDe la EverandAll that the Prophets Have Declared: The Appropriation of Scripture in the Emergence of ChristianityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spirit Empowered Speech-Toward A Pentecostal Apologetical MethodDocument165 paginiSpirit Empowered Speech-Toward A Pentecostal Apologetical MethodKevin B Snider100% (1)

- Themelios40 3Document196 paginiThemelios40 3mateiflorin07Încă nu există evaluări

- Apologetics Research PaperDocument12 paginiApologetics Research PaperJessica ComstockÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACE Consultancy AgreementDocument0 paginiACE Consultancy AgreementjonchkÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Covenant Theology and Futuristic PremillennialismDocument12 paginiNew Covenant Theology and Futuristic Premillennialismsizquier66Încă nu există evaluări

- DRRM School Memo and Letter of InvitationDocument7 paginiDRRM School Memo and Letter of InvitationRames Ely GJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Alexander, T. Desmond, Rosner, Brian (HRSG.) New Dictionary of Biblical TheologyDocument4 paginiReview Alexander, T. Desmond, Rosner, Brian (HRSG.) New Dictionary of Biblical Theologygersand6852Încă nu există evaluări

- Necrowarcasters Cards PDFDocument157 paginiNecrowarcasters Cards PDFFrancisco Dolhabaratz100% (2)

- A Kingdom Called Desire: Confronted by the Love of a Risen KingDe la EverandA Kingdom Called Desire: Confronted by the Love of a Risen KingEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (2)

- Repairing Education Through TruthDocument9 paginiRepairing Education Through Truthapi-259381516Încă nu există evaluări

- Copyreading and Headline Writing Exercise 2 KeyDocument2 paginiCopyreading and Headline Writing Exercise 2 KeyPaul Marcine C. DayogÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30/30 Hindsight: 30 Reflections on a 30-Year Headache: 30 Reflections on a 30-Year HeadacheDe la Everand30/30 Hindsight: 30 Reflections on a 30-Year Headache: 30 Reflections on a 30-Year HeadacheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cumenical Rends: Koinonia and PhiloxeniaDocument5 paginiCumenical Rends: Koinonia and PhiloxeniaMassoviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Bombshell in the Baptistery: An Examination of the Influence of George Beasley-Murray on the Baptismal Writings of Select Southern Baptist and Baptist Union of Great Britain ScholarsDe la EverandA Bombshell in the Baptistery: An Examination of the Influence of George Beasley-Murray on the Baptismal Writings of Select Southern Baptist and Baptist Union of Great Britain ScholarsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dickson Study GuideDocument43 paginiDickson Study Guidexal22950100% (1)

- Calvin's Institutes: Abridged EditionDe la EverandCalvin's Institutes: Abridged EditionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (393)

- Presbyterian Questions, Presbyterian Answers, Revised editionDe la EverandPresbyterian Questions, Presbyterian Answers, Revised editionÎncă nu există evaluări

- The God Who Kneels: A Forty-Day Meditation on John 13De la EverandThe God Who Kneels: A Forty-Day Meditation on John 13Încă nu există evaluări

- Where Did The Church Begin (D.A. Carson)Document8 paginiWhere Did The Church Begin (D.A. Carson)spaghettipaulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joseph-h-hellerman - Morφh Θeoy as a Signifier of Social Status in Philippians 2,6 - Jets-52-779-797Document19 paginiJoseph-h-hellerman - Morφh Θeoy as a Signifier of Social Status in Philippians 2,6 - Jets-52-779-797Vetusta MaiestasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oasis of Imagination: Engaging our World through a Better CreativityDe la EverandOasis of Imagination: Engaging our World through a Better CreativityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of A Little Book For New TheologiansDocument3 paginiReview of A Little Book For New Theologianscreative2009Încă nu există evaluări

- The Problem of PietismDocument4 paginiThe Problem of PietismSteve BornÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sermons from Mind and Heart: Struggling to Preach TheologicallyDe la EverandSermons from Mind and Heart: Struggling to Preach TheologicallyÎncă nu există evaluări

- iPod, YouTube, Wii Play: Theological Engagements with EntertainmentDe la EverandiPod, YouTube, Wii Play: Theological Engagements with EntertainmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tampering With The Trinity: Does The Son Submit To His Father?Document9 paginiTampering With The Trinity: Does The Son Submit To His Father?kaging malabago100% (1)

- The Divine Sabotage: An Expositional Journey through EcclesiastesDe la EverandThe Divine Sabotage: An Expositional Journey through EcclesiastesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Evangelical Presbyterian - Autumn 2016Document24 paginiThe Evangelical Presbyterian - Autumn 2016EPCIrelandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Matt Weymeyers Critique of Infant BaptismDocument2 paginiReview of Matt Weymeyers Critique of Infant Baptismauthorchcobb100% (1)

- Sing Psalms or Hymns, Jeff StivasonDocument5 paginiSing Psalms or Hymns, Jeff StivasonMarcelo SánchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part 11 - Worship - God TransformsDocument10 paginiPart 11 - Worship - God TransformsBradley Sheldon LaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The God Who Comforts: A Forty-Day Meditation on John 14:1—16:15De la EverandThe God Who Comforts: A Forty-Day Meditation on John 14:1—16:15Încă nu există evaluări

- Sutan To 2015Document27 paginiSutan To 2015Robin GuiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hope'S Reason: A Journal of Apologetics 49Document19 paginiHope'S Reason: A Journal of Apologetics 49Ash FoxxÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Primer On Reformed Theology: Part of The Introduction To Spiritual Leadership ConferenceDocument93 paginiA Primer On Reformed Theology: Part of The Introduction To Spiritual Leadership ConferenceChrist Presbyterian Church, New HavenÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Examination of The Songs of Ascents A PDFDocument31 paginiAn Examination of The Songs of Ascents A PDFXavier CasamadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 5 Verbal InspirationDocument8 paginiChapter 5 Verbal InspirationSHD053Încă nu există evaluări

- Faith Seeking UnderstandingDocument37 paginiFaith Seeking UnderstandingEddy EbenezerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Against Karl Rahner S Rule HTTPWWW - Midamerica.eduresourcesjournal15jowersDocument10 paginiAgainst Karl Rahner S Rule HTTPWWW - Midamerica.eduresourcesjournal15jowersdinoydavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ministry Magazine March 2001Document32 paginiMinistry Magazine March 2001Martinez YanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mirrors and Microscopes: Historical Perceptions of BaptistsDe la EverandMirrors and Microscopes: Historical Perceptions of BaptistsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9MarksWeekenderNotebook PDFDocument159 pagini9MarksWeekenderNotebook PDFjohannesjanzen6527Încă nu există evaluări

- 25 3 2020 Explaining PDFDocument15 pagini25 3 2020 Explaining PDFJose Gabriel Pineda MolanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lord's PrayerDocument3 paginiThe Lord's PrayerAlexandru NadabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seven TrumpetsDocument32 paginiSeven TrumpetsLeonardo FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Martin Luther's "Freedom of Christian": Comments by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Document7 paginiMartin Luther's "Freedom of Christian": Comments by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Monika-Maria Grace100% (2)

- DM03-FINAL PAPER-Nouthetic Counseling in The Mediatorial Reign of ChristDocument47 paginiDM03-FINAL PAPER-Nouthetic Counseling in The Mediatorial Reign of ChristJoel Enoch Wood100% (1)

- Van Til: CorneliusDocument20 paginiVan Til: CorneliusLalpu HangsingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is 14394 1996 PDFDocument10 paginiIs 14394 1996 PDFSantosh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEG SchemeDocument13 paginiPEG Schemed-fbuser-120619586Încă nu există evaluări

- Internship Report On Dhaka BankDocument78 paginiInternship Report On Dhaka Bankparvin akhter evaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tab 82Document1 paginăTab 82Harshal GavaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sony SBS Flyer 03Document2 paginiSony SBS Flyer 03rehman0084Încă nu există evaluări

- HLF1036 HousingLoanApplicationCoBorrower V01Document2 paginiHLF1036 HousingLoanApplicationCoBorrower V01Andrei Notario Manila100% (1)

- Vocabulary Quiz 5 Group ADocument1 paginăVocabulary Quiz 5 Group Aanna barchukÎncă nu există evaluări

- About General Aung SanDocument18 paginiAbout General Aung SanThoon Yadanar ShanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idx Monthly August 2021Document139 paginiIdx Monthly August 2021ElinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vasquez Vs CADocument8 paginiVasquez Vs CABerÎncă nu există evaluări

- REQUIREMENTS FOR Bfad Medical Device DistrutorDocument3 paginiREQUIREMENTS FOR Bfad Medical Device DistrutorEvanz Denielle A. OrbonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waf Rosary Group Leaflet - June 2018Document2 paginiWaf Rosary Group Leaflet - June 2018Johnarie CardinalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Accounting Module 2Document85 paginiFinancial Accounting Module 2paul ndhlovuÎncă nu există evaluări

- hp6 Final DraftDocument12 paginihp6 Final Draftapi-389022882Încă nu există evaluări

- SEC Cryptocurrency Enforcement Q3 2013 Q4 2020Document30 paginiSEC Cryptocurrency Enforcement Q3 2013 Q4 2020ForkLogÎncă nu există evaluări

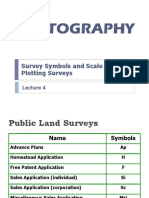

- GE 103 Lecture 4Document13 paginiGE 103 Lecture 4aljonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Contemporary Global GovernanceDocument12 paginiThe Contemporary Global GovernanceSherilyn Picarra100% (1)

- Aetna V WolfDocument2 paginiAetna V WolfJakob EmersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Friday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleDocument11 paginiFriday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleTom TuttleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tyrone Wilson StatementDocument2 paginiTyrone Wilson StatementDaily FreemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument25 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Credit Operations and Risk Management in Commercial BanksDocument4 paginiCredit Operations and Risk Management in Commercial Bankssn nÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics and Truths in Indian Advertising PDFDocument2 paginiEthics and Truths in Indian Advertising PDFTrevorÎncă nu există evaluări