Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Bench Press Syndrome

Încărcat de

Abdallah Maroun NajemDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Bench Press Syndrome

Încărcat de

Abdallah Maroun NajemDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1 of 4

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The bench-pressers shoulder: an overuse insertional

tendinopathy of the pectoralis minor muscle

Deepak N Bhatia, Joe F de Beer, Karin S van Rooyen, Francis Lam, Donald F du Toit

...................................................................................................................................

Br J Sports Med 2007;41:e11 (http://www.bjsportmed.com/cgi/content/full/41/8/e11). doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.032383

See end of article for

authors affiliations

........................

Correspondence to:

Dr D N Bhatia, Cape

Shoulder Institute, Suite no 4,

Medgroup Anlin House, 43

Bloulelie Crescent,

Plattekloof, Cape Town,

South Africa;

thebonesmith@gmail.com

Accepted 29 October 2006

Published Online First

29 November 2006

........................

Background: Tendinopathies of the rotator cuff muscles, biceps tendon and pectoralis major muscle are

common causes of shoulder pain in athletes. Overuse insertional tendinopathy of pectoralis minor is a

previously undescribed cause of shoulder pain in weightlifters/sportsmen.

Objectives: To describe the clinical features, diagnostic tests and results of an overuse insertional tendinopathy of

the pectoralis minor muscle. To also present a new technique of ultrasonographic evaluation and injection of the

pectoralis minor muscle/tendon based on use of standard anatomical landmarks (subscapularis, coracoid process

and axillary artery) as stepwise reference points for ultrasonographic orientation.

Methods: Between 2005 and 2006, seven sportsmen presenting with this condition were diagnosed and

treated at the Cape Shoulder Institute, Cape Town, South Africa.

Results: In five patients, the initiating and aggravating factor was performance of the bench-press exercise

(hence the term bench-pressers shoulder). Medial juxta-coracoid tenderness, a painful active-contraction

test and bench-press manoeuvre, and decrease in pain after ultrasound-guided injection of a local

anaesthetic agent into the enthesis, in the absence of any other clinically/radiologically apparent pathology,

were diagnostic of pectoralis minor insertional tendinopathy. All seven patients were successfully treated with

a single ultrasound-guided injection of a corticosteroid into the enthesis of pectoralis minor followed by a

period of rest and stretching exercises.

Conclusions: This study describes the clinical features and management of pectoralis minor insertional

tendinopathy, secondary to the bench-press type of weightlifting. A new pain site-based classification of

shoulder pathology in weightlifters is suggested.

endinopathies are common in professional and recreational

athletes; different forms have been described on the basis

of the anatomical location of a lesion within the tendon

(enthesis, main body of tendon and structures surrounding the

tendon). Insertional tendinopathy (enthesiopathy) is one of the

most common forms of tendinopathy and can affect any tendon

in the body.1 Tendinopathy of the rotator cuff, long head of

biceps and pectoralis major muscle are often implicated in the

aetiology of shoulder pain in athletes.24

Pectoralis minor is a thin triangular muscle lying deep to the

pectoralis major. It originates from the 3rd, 4th and 5th ribs

near the costal cartilages. Its fibres ascend laterally and

converge in a flat tendon that attaches to the medial border

and upper surface of the coracoid process of the scapula. The

axillary vessels and brachial plexus lie posterior to the muscle

(fig 1). The function of the pectoralis minor is to tilt the scapula

anteriorlythat is, to rotate the scapula about a coronal axis so

that the coracoid process moves anteriorly and caudally, while

the inferior angle moves posteriorly and medially.5 Sporting/

training activities that involve this motion of the scapula

(bench-pressing, swimming and push-up exercises) can theoretically result in overuse of this muscle, especially in the

presence of training errors, poor technique or a rapid increase in

training load, frequency and/or duration.1

This paper presents a previously undescribed condition, an

overuse insertional tendinopathy of the pectoralis minor

muscle, in seven sportsmen. The diagnostic tests and use of

ultrasonography for evaluation of the pectoralis minor muscle/

tendon are presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2005 and 2006, we diagnosed and successfully treated

seven patients (five men, two women) presenting with an

overuse tendinopathy of the pectoralis minor muscle. The mean

age of the patients was 31.6 (range 1762) years. Three patients

were competitive sportsmen (rugby, swimming and bodybuilding) and four were non-competitive ones (recreational

body-building/fitness exercise). The dominant upper extremity

(right shoulder) was involved in three patients and nondominant one (left shoulder) in four patients. In five patients,

the onset was subacute and the pain first occurred after a recent

increase in the bench-press exercise; the mean (range) duration

of symptoms in this group was approximately 4.5 (1.5

12) weeks. In two patients, the onset was gradual (7

9 months) and was related to an increase in sporting activity

in one of them.

All patients were evaluated by clinical, radiographic and

ultrasonographic examinations. Clinical evaluation included a

subjective evaluation of pain and functional status by interview, assessment of glenohumeral stability (apprehension and

translation tests), assessment of rotator cuff integrity (Jobes

test, bear-hug test and strength test using a portable

dynamometer (ISOBEX 2.1, Cursor Ag, Bern, Switzerland)),

assessment of long head of biceps tendon (Speeds test and

Yergasons sign), and examination of the acromioclavicular

joint (tenderness and cross-body adduction).68 In addition,

each shoulder was scored using the Constant and Murley9

method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Radiographic

evaluation in three planes included true anteroposterior,

axillary-lateral and saggital-Y views to exclude stress fractures

or any other bony pathology of the coracoid process, acromioclavicular joint and glenohumeral joint. Ultrasonographic

evaluation included assessment of the rotator cuff, biceps

tendon and bicipital groove.

The pectoralis minor muscle was tested clinically by palpating for an area of tenderness medial to the coracoid along the

www.bjsportmed.com

2 of 4

Bhatia, de Beer, van Rooyen, et al

Cc

Ca

S

Ax

*

3

Sc

C

Pm

Ax

4

5

Figure 1 Overview of anatomy and relationships of the pectoralis minor

muscle. *, coracoid process tip; Ax, axillary artery; C, conjoint tendon; Ca,

coracoacromial ligament; Cc, coracoclavicular ligaments; Pm, pectoralis

minor muscle; S, supraspinatus muscle; Sc, subscapularis muscle; 3, 4, 5,

origin of pectoralis minor muscle from the 3rd, 4th and 5th ribs.

inferior-medial orientation of the muscle fibres. Active contraction of the muscle was tested as described in literature by

Kendall and McCreary5: in the supine position, the patient

thrusts the shoulder forward without exerting any downward

pressure on the hand to force the shoulder forward. The

examiner exerts pressure against the anterior aspect of the

patients shoulder, downward towards the table (fig 2A). A

provocative test (bench-press manoeuvre) was devised to assess

the nature of symptoms experienced by the patients while

performing bench-press exercise. In the supine position, with

both shoulders abducted and elbows flexed at 90 each, the

patient exerts an upward force against resistance (fig 2B).

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the pectoralis minor muscle

consisted of assessment of muscletendon integrity (to exclude

an isolated tear of pectoralis minor muscle) as described in the

following (fig 3A,B). An ameliorative/therapeutic test, consisting of ultrasound-guided injection of a local anaesthetic agent

and a corticosteroid into the insertion of pectoralis minor

tendon (medial juxta-coracoid region), was performed to

confirm and treat the insertional tendinopathy (fig 4).

All seven patients were followed up at 2, 4 and 6 weeks after

the initial assessment. During this period, all sporting activities

related to the upper limb were discontinued and stretching

exercises of the pectoralis minor were prescribed.10 Thereafter,

sporting activity was gradually resumed. A final functional

assessment (clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation, Constant

shoulder score) was performed at 12 weeks after the initial

evaluation.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed to determine

a significant difference between the preoperative and

postoperative Constant scores. The data were analysed using a

data analysis software system (STATISTICA, V.7.1, StatSoft,

Inc., Oklahoma, USA). The preoperative and postoperative

Constant scores were tested for equality of means with analysis

of variance (significance level a = 0.05) and then with the nonparametric Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

Technique of ultrasonographic identification,

evaluation and injection of the pectoralis minor muscle

tendon

Ultrasonographic identification of the pectoralis minor muscle

is performed in a stepwise manner using the subscapularis

muscle, coracoid process and axillary artery as standard and

consistent reference landmarks. The examination proceeds in a

lateral-to-medial direction. The first step is to identify the

subscapularis and to follow it medially to the coracoid process.

A curved array transducer (type C5-2, Sonoline G50 Ultrasound

Imaging System, Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Mountain

View, California, USA) is placed on the proximal part of the

humerus, perpendicular to the intertubercular/bicipital groove,

and then moved medially. This manoeuvre identifies the

insertion of the subscapularis tendon. The subscapularis is

followed medially to the coracoid process, which is visualised as

a strongly echogenic line with an anechoic shadow. This

landmark can be confirmed by internal and external rotation of

the shoulder, which shows a corresponding movement in the

subscapularis under the static coracoid process (fig 3A). The

next step is to identify the pectoralis minor muscle. This is

achieved by moving the transducer further medially, in line

with the orientation of pectoralis minor muscle fibres (inferior

medial to superior lateral). When placed correctly, the axillary

artery can be visualised as a pulsatile anechogenic structure.

This can be further confirmed with the Doppler function of the

system. The pectoralis minor muscle is identified as an

echogenic layer, passing from medial to lateral, bounded

inferiorly by the axillary artery and laterally by the coracoid

process (fig 3B). Dynamic evaluation of the muscle can be

performed by actively thrusting the shoulder forward and

backward; the pectoralis minor is seen contracting and relaxing

with this manoeuvre. The lesser echogenic layer above this is

the pectoralis major muscle. Once the pectoralis minor has been

identified, the probe is centred over the coracoid process. A 21guage needle is passed just medial to the coracoid process and

can be seen entering the insertion of the pectoralis minor

tendon at the coracoid process (fig 4). A solution of a mixture of

a local anaesthetic agent (2 cm3 of lignocaine hydrochloride

1%) with a corticosteroid (1 cm3 of betamethasone acetate

3 mg) is then injected into the tendon and the needle is

withdrawn.

Figure 2 (A) Active contraction test for the pectoralis minor muscle. The patient actively thrusts the shoulder forward (lower arrow) against resistance

exerted by the examiners hand (upper arrow). (B) Bench-press manoeuvre for provocative testing of pectoralis minor insertional tendinopathy. The patient

exerts an upward force (upper arrows) against resistance and mimicking the bench-press exercise. Pain medial to the coracoid (lower arrow) suggests a

positive test.

www.bjsportmed.com

Overuse insertional tendinopathy of pectoralis minor muscle

3 of 4

B

Pm

Pm

Sc

C

Sc

Figure 3 (A) Ultrasonographic visualisation of the anatomical relationship of the subscapularis muscle (Sc), coracoid process (C) and pectoralis minor

tendon (Pm). (B) Ultrasonographic visualisation of the pectoralis minor muscle (Pm) and tendon inserting on the coracoid process (C). The axillary artery (A)

is seen deep to the pectoralis minor muscle. H, humeral head.

RESULTS

All seven patients subjectively described the pain to be

moderate to severe in intensity, limiting their competitive/

recreational sporting and daily activities. In five patients, the

initiating and aggravating factor was the bench-press exercise.

In all seven patients, the glenohumeral joint was stable and

tests for rotator cuff, biceps tendon and acromioclavicular joint

pathology were negative. The mean (range) Constant and

Murley score at initial assessment was 76% (7179%). Threeplane radiographic examination did not show any stress

fractures or other bony/joint abnormality. Ultrasound evaluation showed normal rotator cuff and biceps tendon.

Medial (juxta-coracoid) tenderness, pain in this region on

performance of active contraction test and/or the bench-press

manoeuvre, and immediate reduction/disappearance of this

tenderness/pain after injection of a local anaesthetic agent,

were interpreted as positive tests for pectoralis minor insertional tendinopathy. Medial (juxta-coracoid) pinpoint tenderness was positive in all seven patients. The active contraction

test was positive in five patients, the provocative test (benchpress manoeuvre) was positive in six patients, and the

ameliorative test (ultrasound-guided local anaesthetic injection) was positive in all seven patients.

At the final follow-up (12 weeks), all seven patients had

resumed pre-injury level of sporting activity without any pain/

discomfort. Clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation of the

pectoralis minor muscle was normal and the mean (range)

Constant and Murley score measured approximately 94% (91

96%). The Wilcoxon matched pairs test showed a significant

increase (p,0.05) in the postoperative Constant scores (at final

follow-up) as compared with the preoperative scores.

DISCUSSION

Weight training forms a standard fitness regimen in many

sports. A high incidence of shoulder injuries has been reported

in weightlifters and bodybuilders, and it is suggested that this

may be a consequence of reduced professional supervision,

especially at the amateur level.11 Within the shoulder, tendinopathies of the rotator cuff, long head of biceps and pectoralis

major muscle and osteolysis of the distal clavicle have been

described as complications of weight lifting.14 11 Insertional

tendinopathy of pectoralis minor is a previously undescribed

cause of shoulder pain in weightlifters/sportsmen. This study is

an analysis of clinical and radiological findings in seven such

cases. We describe this condition as Bench-Pressers

Shoulder as the bench-press exercise was the initiating and

aggravating factor in five of the seven cases.

Clinical evaluation of the pectoralis minor muscle was based

on its anatomical location and action. Pectoralis minor tendon

is the only significant structure that inserts on the medial

surface of the coracoid process. Medial juxta-coracoid tenderness would therefore suggest pathology of the pectoralis minor

enthesis. Pain resulting from the active contraction test and the

bench-press manoeuvre, both of which result in contraction of

pectoralis minor, also suggests a role of pectoralis minor

muscle/enthesis. Confirmation of pectoralis minor insertional

tendinopathy can be concurred by immediate reduction/

disappearance of the pain (tenderness and test-induced pain)

Table 1 A pain-site-based classification of pathology in a

weight-training athlete

Pain site

Probable pathology

Top of shoulder

(acromioclavicular joint)

Lateral to coracoid

Osteolysis of distal clavicle, acromioclavicular

joint arthritis

Bicipital tendinopathy, rotator cuff

tendinopathy/rupture, pectoralis major

tendinopathy/rupture

Pectoralis minor insertional tendinopathy

Subcoracoid impingement

Medial juxta-coracoid

Lateral juxta-coracoid

Figure 4 Position of the transducer and injection site for ultrasoundguided injection of the pectoralis minor tendon.

www.bjsportmed.com

4 of 4

What is already known on this topic

The shoulder is the most often injured joint in weightlifters. Within the shoulder, tendinopathies of the rotator

cuff, long head of biceps and pectoralis major muscle,

and osteolysis of the distal clavicle have been described

in aetiology of shoulder pain in weight-lifting athletes.

What this study adds

N

N

This study describes the clinical features and management of a previously undescribed condition of pectoralis

minor insertional tendinopathy, secondary to benchpress type of weightlifting.

A simplified technique of ultrasound-guided injection of

the pectoralis minor enthesis is described. A new painsite-based classification of shoulder pathology in weightlifters is suggested.

Bhatia, de Beer, van Rooyen, et al

In summary, we consider the following to be suggestive of an

overuse tendinopathy of the pectoralis minor:

N

N

N

N

N

N

medial juxta-coracoid pain/tenderness;

aggravated by active contraction of the pectoralis minor

muscle;

reproduced by the bench-press manoeuvre;

relieved by injection of a local anaesthetic into the tendon

insertion;

ultrasonographically intact pectoralis minor muscle;

absence of any other clinically/radiologically apparent

shoulder pathology.

.......................

Authors affiliations

Deepak N Bhatia, Joe F de Beer, Karin S van Rooyen, Francis Lam, Cape

Shoulder Institute, Plattekloof, Cape Town, South Africa

Donald F du Toit, Department of Anatomy, University of Stellenbosch,

Plattekloof, Cape Town, South Africa

Competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

after injection of a local anaesthetic agent into the insertion

site, under ultrasound guidance.

Ultrasound evaluation of the pectoralis minor can be used to

assess the integrity of the pectoralis minor tendon and to inject

a local anaesthetic/corticosteroid into the insertion site. The

technique described here is a simplified method, based on using

standard anatomical landmarks for identification of the tendon

and localisation of the insertion site. The subscapularis muscle,

coracoid process and axillary artery are stepwise reference

points that lead the examiner to the pectoralis minor muscle.

Evaluation of the entire tendon is necessary to exclude the

diagnosis of an isolated tear of the pectoralis minor, although

this has been reported only once in literature.12 Corticosteroidinduced tendon ruptures and resultant pain relief are known.

Hence, follow-up ultrasonographic evaluation of the tendon

was performed to assess the status of the muscle/tendon of

pectoralis minor.

We successfully treated this condition with a single ultrasound-guided injection of a corticosteroid into the enthesis, a

period of rest and stretching exercises for pectoralis minor

muscle (6 weeks) and thereafter, gradual progression to preinjury level of sporting activity (6 weeks).10 1214 On the basis of

the results of this study and a review of literature, a simple

symptom-related algorithmic approach to shoulder pain in a

weight-training athlete can be suggested (table 1). 24 11 15

www.bjsportmed.com

1 Maganaris CN, Narici MV, Almekinders LC, et al. Biomechanics and

pathophysiology of overuse tendon injuries: ideas on insertional tendinopathy.

Sports Med 2004;34:100517.

2 Teitz CC, Garrett WE Jr, Miniaci A, et al. Instructional Course Lectures, The

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeonstendon problems in athletic

individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:13852.

3 Chadwick CJ. Tendinitis of the pectoralis major insertion with humeral lesions: A

report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989;71:81618.

4 Marone PJ. Shoulder injuries in sports. London: Martin Dunitz, 1992:4768.

5 Kendall FP, McCreary EK. Muscles: testing and function, 3rd edn. Baltimore/

London: Williams & Wilkins, 1983:106.

6 Tennent TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with

shoulder examination. Part I: the rotator cuff tests. Am J Sports Med

2003;31:15460.

7 Tennent TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests

associated with shoulder examination. Part II: laxity, instability, and

superior labral anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions. Am J Sports Med

2003;31:3017.

8 Barth JRH, Burkhart SS, de Beer, JF. The bear-hug test: a new and sensitive test

for diagnosing a subscapularis tear. Arthroscopy 2006;22:107684.

9 Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the

shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;214:1604.

10 Borstad JD, Ludewig PM. Comparison of three stretches for the pectoralis minor

muscle. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15:32430.

11 Van der Wall H, McLaughlin A, Bruce W, et al. Scintigraphic patterns of injury in

amateur weight lifters. Clin Nucl Med 1999;24:91520.

12 Mehallo CJ. Isolated tear of the pectoralis minor. Clin J Sport Med

2004;14:2456.

13 Speed CA. Corticosteroid injections in tendon lesions. BMJ 2001;323:3826.

14 Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies:

update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med

1999;27:393408.

15 Ferrick MR. Coracoid Impingement: a case report and review of literature.

Am J Sports Med 2000;28:11719.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Y ExercisesDocument4 paginiY ExercisesTroy Byall100% (1)

- CBB - Program Phase 1Document4 paginiCBB - Program Phase 1Titus BaldwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molecular and Cellular Aspects of Muscle Function: Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of Physiological Sciences Budapest 1980, (including the proceedings of the satellite symposium on Membrane Control of Skeletal Muscle Function)De la EverandMolecular and Cellular Aspects of Muscle Function: Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of Physiological Sciences Budapest 1980, (including the proceedings of the satellite symposium on Membrane Control of Skeletal Muscle Function)E. VargaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protocol Hamstring Lengthened Eccentric Training 15214 PDFDocument9 paginiProtocol Hamstring Lengthened Eccentric Training 15214 PDFkang soon cheolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Girls and Sport: Female Athlete Triad SimplifiedDe la EverandGirls and Sport: Female Athlete Triad SimplifiedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Injury Prevention in Youth Sports.Document5 paginiInjury Prevention in Youth Sports.drmanupvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physical Agility Test Preparation and Safety: How To Prepare For The PATDocument9 paginiPhysical Agility Test Preparation and Safety: How To Prepare For The PATJmFormalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Landing MechanicsDocument4 paginiLanding MechanicsYunus YataganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balance TrainingDocument12 paginiBalance TrainingMahdicheraghi100% (1)

- The 25% - 75% Rule Year-Round Training With Discipline and ToughnessDocument5 paginiThe 25% - 75% Rule Year-Round Training With Discipline and ToughnessSBD4lifeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Term Effects of Complex and ContrastDocument6 paginiShort Term Effects of Complex and ContrastKoordinacijska Lestev Speed LadderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agility and Perturbation TrainingDocument19 paginiAgility and Perturbation TrainingzumantaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 - RecoveryDocument20 paginiChapter 11 - RecoveryDDVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Costa Rica GlucoseDocument91 paginiCosta Rica GlucoseAnthony HarderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optimal Shoulder Performance - Cressey ReinoldDocument40 paginiOptimal Shoulder Performance - Cressey Reinolddr_finch511Încă nu există evaluări

- Teaching The Power CleanDocument54 paginiTeaching The Power CleanStu Skalla GrimsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 - Reciprocal InnervationDocument19 pagini11 - Reciprocal InnervationGaming ProÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plyometric Training Considerations To Reduce Knee.18 PDFDocument3 paginiPlyometric Training Considerations To Reduce Knee.18 PDFAndrew ShirekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classic GPP For High School FreshmenDocument4 paginiClassic GPP For High School FreshmenxceelentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westside Conjugate CalculatorDocument10 paginiWestside Conjugate Calculatorp300644Încă nu există evaluări

- Double Play: Training and Nutrition Advice from the World's Experts in BaseballDe la EverandDouble Play: Training and Nutrition Advice from the World's Experts in BaseballÎncă nu există evaluări

- Max Efforts Upper BodyDocument3 paginiMax Efforts Upper BodyDieter PolletÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insight From The ExpertsDocument44 paginiInsight From The Expertsjdrosenb100% (1)

- The Youth Athlete: A Practitioner’s Guide to Providing Comprehensive Sports Medicine CareDe la EverandThe Youth Athlete: A Practitioner’s Guide to Providing Comprehensive Sports Medicine CareBrian J. KrabakÎncă nu există evaluări

- PeriodizationDocument3 paginiPeriodizationAdam ZulkifliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jumps - Plyos - Phase 1 - Upside StrengthDocument1 paginăJumps - Plyos - Phase 1 - Upside Strengthok okÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eccentric Exercise Program Design - A Periodization Model For Rehabilitation ApplicationsDocument37 paginiEccentric Exercise Program Design - A Periodization Model For Rehabilitation ApplicationsDeivison Fellipe da Silva CâmaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book 3: Fitness Analysis for Sport: Academy of Excellence for Coaching of Fitness DrillsDe la EverandBook 3: Fitness Analysis for Sport: Academy of Excellence for Coaching of Fitness DrillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 12 - Injuries and Medical Care PDFDocument83 paginiChapter 12 - Injuries and Medical Care PDFDDVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warm Ups RAMPDocument19 paginiWarm Ups RAMPRichard Jerome Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eccentric IsometricDocument658 paginiEccentric Isometricradarm2018555Încă nu există evaluări

- CrossFit Study (Final)Document67 paginiCrossFit Study (Final)Branimir SoljicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Justification of Training Plan-Baseball: Name: Zack Cullen Student Number: HYC50075809Document8 paginiJustification of Training Plan-Baseball: Name: Zack Cullen Student Number: HYC50075809Zack StylesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Guidelines For Plyometric Intensity: PlyometricsDocument5 paginiPractical Guidelines For Plyometric Intensity: PlyometricsDDVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dysfunctional Breathing: The Functional Screening Frequently ForgottenDocument24 paginiDysfunctional Breathing: The Functional Screening Frequently ForgottenHONGJYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition For Optimal Sports Performance: A Comprehensive GuideDocument95 paginiNutrition For Optimal Sports Performance: A Comprehensive Guidedsandos2001Încă nu există evaluări

- Core StiffnessMcGill 2015Document12 paginiCore StiffnessMcGill 2015Hugo TintiÎncă nu există evaluări

- VBT Annual Plan Dave BallouDocument8 paginiVBT Annual Plan Dave BallouEthan AtchleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Linear and Daily UndulatingDocument20 paginiEffects of Linear and Daily UndulatingNATHALIA MARIA TORRES DA SILVAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Eccentric Versus Concentric Resistance Training On Muscle Strength and Mass in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review With Meta-AnalysisDocument14 paginiThe Effects of Eccentric Versus Concentric Resistance Training On Muscle Strength and Mass in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review With Meta-AnalysisPerico PalotesÎncă nu există evaluări

- FUNHAB®: A Science-Based, Multimodal Approach For Musculoskeletal ConditionsDocument9 paginiFUNHAB®: A Science-Based, Multimodal Approach For Musculoskeletal ConditionsVizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2022 12 30 Website PDFDocument80 pagini2022 12 30 Website PDFmostafakhafagy8Încă nu există evaluări

- Modified Daily Undulating Periodization PDFDocument8 paginiModified Daily Undulating Periodization PDFluigiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Max Sheet Break Down Final 2 Test Back SquatDocument3 paginiMax Sheet Break Down Final 2 Test Back SquatRichard Marcus SeigelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westside TemplateDocument3 paginiWestside TemplateSteven Yeti Griffiths100% (1)

- Love Your Bones: The essential guiding to ending osteoporosis and building a healthy skeletonDe la EverandLove Your Bones: The essential guiding to ending osteoporosis and building a healthy skeletonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golf Performance ManualDocument35 paginiGolf Performance ManualHemang PanditÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesDocument11 paginiEccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesAnonymous xvlg4m5xLXÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tri-Phasic Epigenetic Model of Self-AcceptanceDocument1 paginăTri-Phasic Epigenetic Model of Self-AcceptanceLucÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Read A Training ProgramDocument13 paginiHow To Read A Training ProgramjapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lower Extremity Stretching ProtocolDocument3 paginiLower Extremity Stretching ProtocolHello RainbowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 14 - Long Term Athletic Development in GymnasticsDocument12 paginiChapter 14 - Long Term Athletic Development in GymnasticsDDVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boyle Phase 2 NHLDocument1 paginăBoyle Phase 2 NHLgamatttaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Functional Movement Screen and Y-Balance Test: Validity in Hamstring Injury Risk Prediction?Document74 paginiFunctional Movement Screen and Y-Balance Test: Validity in Hamstring Injury Risk Prediction?NICOLÁS ANDRÉS AYELEF PARRAGUEZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basketball Strength & Conditioning: General PreparationDocument4 paginiBasketball Strength & Conditioning: General PreparationBaba HansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal Training ExercisesDocument4 paginiPersonal Training Exercisesapi-377252439Încă nu există evaluări

- Crossover Scaling Shoulder Guide 1Document6 paginiCrossover Scaling Shoulder Guide 1Alexandru SeciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workout ProgramDocument5 paginiWorkout Programhanus.milannseznam.czÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 9 - Cardio and ESD PDFDocument28 paginiChapter 9 - Cardio and ESD PDFDDVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Center Fueled By: Womens's Basketball Off-Season Level II StrengthDocument12 paginiPerformance Center Fueled By: Womens's Basketball Off-Season Level II Strengththeshow31Încă nu există evaluări

- FMSP1 PDFDocument126 paginiFMSP1 PDFPikaboo31100% (1)

- Jeremy Lewis Shoulder T and P 22nd EdDocument3 paginiJeremy Lewis Shoulder T and P 22nd EdDr Abdallah BahaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Anatomy of The ShoulderDocument11 paginiApplied Anatomy of The ShoulderSamantha HohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final ManuscriptDocument43 paginiFinal Manuscriptapi-372150835Încă nu există evaluări

- Diseases and Disorders of The Skeletal SystemDocument32 paginiDiseases and Disorders of The Skeletal SystemPatrisha Georgia AmitenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adhesive Capsulitis of The Shoulder: Protocol For The Adhesive Capsulitis Biomarker (Adcab) StudyDocument6 paginiAdhesive Capsulitis of The Shoulder: Protocol For The Adhesive Capsulitis Biomarker (Adcab) StudyRuben FigueroaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schwerla 2020Document8 paginiSchwerla 2020João Paulo Vila Nova GomesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoulder Guidelines AdhesiveCapsulitis JOSPT May 2013 PDFDocument31 paginiShoulder Guidelines AdhesiveCapsulitis JOSPT May 2013 PDFElliya RosyidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outsmart Pain E-BookDocument69 paginiOutsmart Pain E-BookMed AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence Based Nursing Stroke 1Document6 paginiEvidence Based Nursing Stroke 1Connie SianiparÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fascial Distortion Model - Vol.4Document76 paginiFascial Distortion Model - Vol.4Magno FilhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Taping As A Component of Conservative Treatment For Subacromial Impingement SyndromeDocument5 paginiEffect of Taping As A Component of Conservative Treatment For Subacromial Impingement SyndromeMohamed KassimÎncă nu există evaluări

- All Pages v3Document142 paginiAll Pages v3luh martaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rheumatology: - Syrian - Notes - CK - 2 - Step - Usmle - Pieces/8806 - Bits - CK - 2 - Step - Student - HTMLDocument5 paginiRheumatology: - Syrian - Notes - CK - 2 - Step - Usmle - Pieces/8806 - Bits - CK - 2 - Step - Student - HTMLLoyla RoseÎncă nu există evaluări

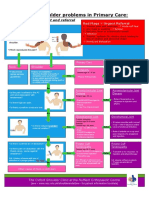

- Rotator Cuff Shoulder Pain DiagnosticDocument14 paginiRotator Cuff Shoulder Pain DiagnosticTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- MKSAP Questions: Intern ReportDocument37 paginiMKSAP Questions: Intern Reportfidelurtecho4881Încă nu există evaluări

- Ultrasound-Guided Shoulder Injections in The Treatment of Subacromial BursitisDocument34 paginiUltrasound-Guided Shoulder Injections in The Treatment of Subacromial Bursitisneo079Încă nu există evaluări

- 107 Rotator Cuff Exercises - Zach CalhoonDocument136 pagini107 Rotator Cuff Exercises - Zach CalhoonSam Gregory100% (2)

- Assignment Shoulder JointDocument7 paginiAssignment Shoulder JointMary Grace OrozcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NHS UK Diagnosis of Shoulder ProblemsDocument1 paginăNHS UK Diagnosis of Shoulder ProblemsmertÎncă nu există evaluări

- LabralDocument5 paginiLabralcrisanto ValdezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 2519@jospt 2020 0501 PDFDocument1 pagină10 2519@jospt 2020 0501 PDFArnold BarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 - Orthopedic HistoryDocument7 pagini4 - Orthopedic HistoryshaifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevention of Shoulder Injuries in Overhead AthletesDocument9 paginiPrevention of Shoulder Injuries in Overhead AthletesLeonardiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cools 2008 Screening The Athletes Shoulder ForDocument9 paginiCools 2008 Screening The Athletes Shoulder ForLucyFloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biceps Tendinitis Caused by An Osteochondroma In.37Document4 paginiBiceps Tendinitis Caused by An Osteochondroma In.37harshini prakashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sindrome Do Nervo SupraescapularDocument9 paginiSindrome Do Nervo SupraescapularAna CarolineÎncă nu există evaluări

- POMR 復健科Document6 paginiPOMR 復健科屏頂大Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Scapular Protraction On Isometric Shoulder Rotation Strength in Normal SubjectsDocument5 paginiThe Effect of Scapular Protraction On Isometric Shoulder Rotation Strength in Normal SubjectskinemasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 3 Rotator Cuff Exercises (Fix Your Shoulder Pain)Document23 paginiTop 3 Rotator Cuff Exercises (Fix Your Shoulder Pain)Nicolas AlonsoÎncă nu există evaluări