Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Multilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global Governance

Încărcat de

Valdai Discussion ClubTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Multilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global Governance

Încărcat de

Valdai Discussion ClubDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Valdai Papers

#22 | July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The

New World of Global Governance

Stewart Patrick

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

Among the many casualties of Barack Obamas presidency has been the illusion that the time is ripe

to overhaul the multilateral systemand that the United States is poised to lead this transformation.

Back in 2007, then-candidate Obama pledged that if elected he would not only reverse the disastrous

unilateralism of the George W. Bush years but spearhead a new era of international cooperation. In

the mid-1940s, far-sighted American leaders had built the system of international institutions that

carried us through the Cold War. 1 Todays challenge was to update these creaky organizations to

twenty-first century threats and opportunities.

Alas, Obamas vision was based on two shaky premises. The first was that the main object of

statecraft was no longer navigating great power rivalries, as in the past, but managing the shared

vulnerabilities of interdependence. As the president declared in his first National Security Strategy,

power, in an interdependent world, is no longer a zero-sum game. 2 The second was that the United

States had the capacity and will to engineer a grand bargain between established and rising powers on

the contours of institutional reform. Established players would grant emerging players a seat at the

global high table. In return, rising powers would help to sustain and manage an agreed global order.

Both assumptions proved wrong. This was not a moment of creationor even of re-creationakin

to the mid-1940s. The world remains far more conflictual, more red-in-tooth-and-claw, than Obamas

technocratic vision of world politics suggests. And even where broad interests and values are aligned,

formal international organizations resist fundamental reform. Despite massive changes in the global

distribution of power, for instance, permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council

(UNSC) remains unchanged since 1945. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), meanwhile, has not

implemented governance reforms laboriously negotiated in 2010, thanks to resistance on Capitol Hill.

That is the bad news about global governance. The good news is that international cooperation still

flourishes within a diverse, dense, and expanding ecosystem of alternative frameworks of collective

action. To be sure, the United States and other governments remain members of anchor institutions

like the UN, World Bank, IMF, and WTO. But, when confronting logjams in such formal, universal

bodies, U.S. and foreign policymakers increasingly pursue their national objectives through narrower

and more flexible frameworks whose membership varies with situational interests, shared values, and

relevant capabilities. In sum, governments increasingly bypass formal international organizations for

a more nimble approach to international cooperation.

Pundits and scholars have given this phenomenon various labels, among them multimultilateralism, minilateralism, plurilateralism, messy multilateralism, contested

multilateralism, and networked global governance. 3 I prefer multilateralism la cartea phrase

1Remarks

of Senator Barack Obama to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, April 23, 2007.

http://www.cfr.org/elections/remarks-senator-barack-obama-chicago-council-global-affairs/p13172

2 The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: 2010).

3 Francis Fukuyama Fukuyama, America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power, and the Neoconservative Legacy (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 155-180. Moises Naim, Minilateralism: The Magic Number to Get Real International Action,

Foreign Policy (June 21, 2009), http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/06/21/minilateralism/. Miles Kahler, Multilateralism with

Small and Large Numbers, International Organization (1992). Richard N. Haass, The Case for Messy Multilateralism,

Financial Times. Julia C. Morse and Robert O. Keohane, Contested Multilateralism, Review of International Organizations (23

March, 2014) http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11558-014-9188-2; Anne-Marie Slaughter, The Real World Order

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

that distinguishes it from the prix fixe menu of international organizations.4 But whatever one calls

it, its basic contours clear. It implies cooperative frameworks that are ad hoc instead of standing and

permanent; informal and voluntary rather than formal and legally binding; disaggregated as opposed

to comprehensive; trans-governmental instead of inter-governmental; and (often) multi-level and

multi-stakeholder rather than purely state-centric.

But what accounts for the rise of la carte multilateralism? What forms has it taken in different

areas? Most importantly, is this variable geometry a good or a bad thing, on balance?

At first blush, flexible multilateralism has much to recommend it. Rather than relying on obsolete,

sclerotic institutions, governments can create new ones adapted to present geopolitics and fit for

purpose. Such a selective and ad hoc approach seems particularly attractive to the United States

which, thanks to its still unmatched power, has unrivaled ability to pick and choose among alternative

coalitions and networksexpanding its diplomatic options and freedom of action in the process.

Still, the hypothetical rewards of multilateralism la carte should not blind us to its potential

drawbacks. The risk of rampant international ad hockery is that it will fail to deliver results, while

undercutting formal organizations upon which the world continues to depend.

The Context: Blockage in Global Governance Reform

In retrospect, it should have been clear to the Obama administration how far removed our era is from

the 1940sand how fierce are the headwinds against global governance reform. Four major

differences between our own world and that of the wise men make reconfiguring the bedrock

institutions of world order a Herculean challenge.

First, the world is no longer a clean slate. In the 1940s, U.S. architects of postwar order could design

institutions out of whole cloth, without dismantling existing institutions or reallocating power and

privilege within them. They were, as Dean Acheson titled his memoirs, present at the creation. The

Obama administration has no such luxury, and confronts a landscape teeming with international

organizations and treaties. Today, the United States is party to over six hundred multilateral treaties

(to say nothing of thousands of bilateral treaties). Member states and agency bureaucrats fiercely

resist efforts to alter the mandate, membership, management, and funding of existing treaty bodies.

Consider the UN Security Council, to which Russia and China adamantly oppose adding any

permanent membersor the International Energy Agency (IEA), whose own membership remains

limited to OECD countries and in which voting shares still reflect oil consumption in the mid-1970s.

Within the UN system, especially, retrofitting existing institutions has proven even more daunting

than creating them in the first placeencouraging the search for workarounds.

4

Stewart Patrick, Prix Fixe and la Carte: Avoiding False Multilateral Choices, The Washington Quarterly. The phrase

multilateralism la carte was originally coined by Richard Haass in 2001: See Thom Shanker, White House Says the U.S. Is

Not a Loner, Just Choosy, New York Times, July 31, 2001, http://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/31/world/white-house-saystheus-is-not-a-loner-just-choosy.html

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

Second, the urgency of the 1940s is absent. In the absence of major policy failure, institutions evolve

incrementally at best. In a perverse way, Achesons generation had it easy, operating on the heels of

the most devastating economic crisis and most destructive war in human history. Our generation has

been spared such catastrophes, but the very absence of crisis reinforces institutional inertia. The

exception that proves the rule is the Great Recession of 2007-2008, when fears of economic

implosion created a transitory incentive for world leaders to adopt significant reforms to global

economic governance, including by elevating the Group of 20 (G20) to the leaders level, creating a

new Financial Stability Board, and adopting the Basel Three capital account requirements for major

banks.

Third, the global agenda is more ambitious and intrusive than immediately after World War II,

making major breakthroughs elusive. Much of the low-hanging fruit of multilateral cooperation has

long been picked. Consider trade: Early GATT rounds focused on lowering tariffs and eliminating

subsidies. Much of todays trade agenda is about harmonizing behind-the-border standards and

regulations on matters like fiscal policy, health and safety, or intellectual property. Such agreements

impinge deeply on state sovereignty. The world is also more crowdedwith states. At its founding,

the UN had only fifty members. Today it has 193, many wedded to bloc identities and entrenched

regional positions, complicating global consensus within forums like the General Assembly.

Fourth, the global distribution of power has changed since the 1940s. The Roosevelt and Truman

administration operated at the zenith of American hegemony. During the Cold War decades, the

United States and its Western allies dominated the capitalist world economy. By 1990, the members

of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) represented more than

three-fifths of global GDP. Today, the OECD share has slipped to 47 percent, despite the addition of a

dozen new members, while the BRICS countries account for almost 25 percent of global output.

To the degree that emerging and established countries share values and preferences, this power shift

can be managed. But integrating emerging powers is not just about a matter of offering them a place

at the global high table and expecting them to foot the bill. It implies allowing them to shape the

agenda. Unfortunately, major Western and non-Western countries often diverge over important

international norms, such as the boundaries of national sovereignty, the criteria for humanitarian

intervention, the role of the state in the market, and the balance between security and civil liberties.

Such considerations help explain why the Obama administration has chosen not to pursue Security

Council reform, despite its initial sympathy for that agenda. Senior U.S. officials ultimately concluded

that the most likely developing world aspirants to permanent membershipeven fellow democracies

like India, Brazil or South Africawould often oppose U.S. preferences.

The Reaction: Multilateralism, la Carte

Faced with blockages in formal international organizations, the Obama administration and its

counterparts abroad are increasingly experimenting with informal, ad hoc, and selective approaches

to global cooperation. While there is no single model of la carte multilateralism, four recurrent

features stand out.

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

The first is reliance on flexible, purpose-built groupings of the interested, capable, and/or

likeminded. In recent years, analysts have debated whether we live in a G2, a G20, or even a G Zero

world.5 In truth, ours is a G-x world in which the entity and number of parties at the head table

varies by issue area and situation. 6 Thus, even as the United States recognizes the G20 as the premier

forum for global economic coordination, it has redoubled its attachment to the G7 (with authoritarian

Russia ejected from the G8) as a narrower partnership of advanced market democracies whose

members share values, interests and policy preferences. At times, a G-x approach to global

governance may produce unusual coalitions, such as the armada formed to combat Somali piracy in

the Indian Ocean. It included vessels not only from the United States and its NATO allies but also

from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea, among others.

Another feature of this flexible multilateralism is informalitynamely, a preference for voluntary

commitments over binding conventions. After two decades of fruitless negotiations over a treaty to

succeed the Kyoto Protocol, the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCC) have adopted a looser pledge and review system. Endorsed at the Lima COP 20 in

December 2014, this approach leaves it to each state to determine how it will contribute to global

emissions reductions. Parties agree to publish online their intended nationally determined

contributions, allowing peers (as well as scientists) to assess their impact. The Nuclear Security

Summit process has involved something similar, with governments expected to arrive with voluntary

gift baskets enumerating separate national commitments.

Governments are also making greater use of codes of conduct. This is particularly true in the global

commons, as these become increasingly congested, competitive, and contested.7 Consider outer

space. The emergence of new space-faring nations like China, Brazil, and India, as well as dozens of

private space companies requires common international rules of the road to mitigate debris, reduce

risks of collision, and discourage militarization in outer space. Rather than trying to update the fiftyyear old Outer Space Treaty, however, the United States endorses internationalizing the non-binding

European Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities to establish parameters for responsible

behavior.8

The third recurrent theme is a piecemeal rather than comprehensive approach to global governance.

Instead of trying to solve a complicated global puzzle like climate change in one fell swoop, as if it

were a Rubiks cube, governments are pursuing global governance in pieces, 9 breaking complex

problems down into component parts. In the global health arena, the World Health Organization now

shares space with other bodies and initiatives, ranging from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and

Immunizations (GAVI) to the Global Health Security Agenda, UNAIDS, and the Global Fund for

Fred Bergsten, A Partnership of Equals, Foreign Affairs (July/August 2008). Ian Bremmer, Every Nation for Itself: Winners

and Losers in a G-Zero World (New York: Penguin, 2012).

6 Alan Alexandroff, Challenges in Global Governance: Opportunities for G-X Leadership, Stanley Foundation Policy Analysis

Brief, March 2010, http://www.stanleyfoundation.org/publications/pab/AlexandroffPAB310.pdf

7 Stewart Patrick, Conflict and Cooperation in the Global Commons, in Chester Crocker, Fen Hampson, and Pamela Aall,

Conflict Management in a Turbulent World (Washington: United States Institute of Peace, 2015).

8 Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities, press statement,

January 17, 2012, US Department of State,

http://www.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2012/01/180969.htm?goMobile=0

9 Stewart Patrick, The Unruled World: The Case for Good Enough Global Governance, Foreign Affairs (January-February

2014)

5

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. 10 An analogous regime complex is arising for cyberspace, with

different institutions tailored to specific issues like cybercrime, data protection, technical standards

and internet governance.11

The fourth distinctive attribute of todays multilateralism is a shift from traditional

intergovernmental diplomacy toward reliance on alternative forms arrangements that are

transgovernmental, multi-level, and multi-stakeholder. To begin with, foreign ministries have lost

their monopoly over multilateral cooperation. Faced with complex challenges of globalization,

national regulators and technical experts now engage their counterparts abroad directly, on an

ongoing basis. Consider the problem of ensuring the safety and reliability of medicines in an era of

complex supply chains. Recognizing its own limitations, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has

spearheaded the creation of an informal global coalition of medicines regulators, intended to close

global gaps in pharmacovigilance, particularly in major producers like China and India. 12

Once the exclusive preserve of states, effective international cooperation now depends on innovative

partnerships between states and non-state actors, both private and public. States, private companies,

and civil society have jointly created multi-stakeholder mechanisms to serve as regulatory and

standard-setting bodies, leveraging the capabilities of different stakeholders. 13 Perhaps the most

well-known arrangement of this sort is the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers

(ICANN), an independent, nonprofit entity that operates under license from the U.S. Department of

Commerce. Multi-stakeholder bodies are especially prominent when it comes to promoting global

health (e.g., GAVI and the Global Fund) and in the regulation of conflict minerals (e.g., Extractive

Industries Transparency Initiative and the Kimberly Process).

Lastly, contemporary global governance is multi-level. As humanity urbanizes, networks of cities are

emerging as dynamic centers of policy innovation. Three years ago at the UN Conference at

Sustainable Development in Rio, a coalition of mayors from around the world (including Michael

Bloomberg of New York) announced a new confederation of citiesthe C-40dedicated to combating

pollution and sustaining green growth. 14 More recently, at the Lima COP 20, UNFCCC members

endorsed a standardized mechanism for cities, provinces and regions to report carbon emissions.

The Limits of Ad Hockery

David P. Fidler, The Challenges of Global Health Governance, CFR Working Paper (Council on Foreign Relations, May

2010), http://www.cfr.org/global-governance/challenges-global-health-governance/p22202

11Joseph S. Nye, The Regime Complex for Managing Cyber Activities, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

(November 2014),

http://belfercenter.hks.harvard.edu/publication/24797/regime_complex_for_managing_global_cyber_activities.html?breadcr

umb=%2Fexperts%2F3%2Fjoseph_s_nye

12 Stewart M. Patrick and Jeffrey A. Wright, Designing a Global Coalition of Medicines Regulators, Policy Innovation

Memorandum No. 48, Council on Foreign Relations (August 20, 2014), http://www.cfr.org/pharmaceuticals-andvaccines/designing-global-coalition-medicines-regulators/p33100

13 Kenneth W. Abbott and Duncan Snidal, The Governance Triangle: Regulatory Standards Institutions and the Shadow of the

State, in Walter Mattli and Ngaire Woods, eds., The Politics of Global Regulation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,

2009), 40-88

14 Benjamin R. Barber, If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities (New Haven: Yale University Press,

2013).

10

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

But is all this institutional diversity a good thingand what does it mean for the United States? In

principle, access to multiple forums could bring multiple benefits, including speed, flexibility,

modularity, and opportunities to experiment. An la carte world would seem especially attractive to

the United States, which has an unmatched ability to create and pivot nimbly among purpose-built

mini-lateral coalitions.

It would be a mistake, however, to ignore the limits and risks of ad hoc multilateralism as a

foundation for U.S. foreign policy, much less for international order. To begin with, it is not yet clear

that la carte multilateralism can actually deliver what formal organizations have not. The

disappointing record of the Major Economies Forum (MEF) provides a cautionary tale. The Obama

administration had hoped that this grouping, comprised of the seventeen largest CO2 emitters, would

help break stalled negotiations within the UNFCCC. Its actual achievements have been negligible. Nor

has the bottom-up, pledge and review process UNFCCC members endorsed in December 2014

delivered on its promise. This raises a larger issue: how credible should one regard commitments that

lack the force of law or any enforcement?

More generally, flexible minilateralism is unlikely to resolve tough cooperation problems when great

power interests and preferences diverge strongly. la carte arrangements are most promising when

participants interests and preferences are broadly congruent, but more encompassing bodies are

blocked. If interests diverge significantlyas in the clashes between Russia and the West over

Crimea, or between China and its neighbors in the South China Seasimply shifting forums is no

panacea. Another obvious drawback to creating new frameworks for each challengebeyond the

obvious transaction costsis that it is harder to negotiate grand bargains across multiple issue areas,

trading concessions in one area for gains in another.

Too great a reliance on ad-hockery may also do damage to formal institutions that have unique

legitimacy grounded in international law and whose technical capabilities and financial resources are

essential over the long term. Though there is some value in giving tired organizations healthy

competition, the worry is that it will lead member states to marginalize rather than reform these

bodies, and that a proliferation of new forums will create wasteful redundancies and global

fragmentation.

A world of multi-multilateralism also encourages rampant forum-shoppingand not only by the

United States. Emerging powers are moving swiftly to sponsor alternative institutions of their own,

ranging from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to the BRICS Bank, the BRICS Contingency

Fund, and (most recently) the and Beijing-led Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB). The

failure of the Obama administration to dissuade even its closest European allies from joining the AIIB

as founding members offered a stark lesson that others can play this game too.

Finally, the rise of la carte multilateralism raises questions of equity and accountability. Global

governance by coalitions tends to privilege great power dominance within exclusive clubs over more

egalitarian approaches to global governance in formal organizations with universal membership.

Since its creation in November 2008, countries left outside of the G20 (the G-173, if you will) have

complained that the new forum is becoming a global directorate, excluding smaller, poorer nations

#22, July 2015

Multilateralism la Carte: The New World of Global Governance

from deliberations and decisions that have a profound impact on their fate. Though power dynamics

are never behind the scene in world politics, formal international organizations grounded in

international law tend to provide weaker players with opportunities to have their views, as well as

mechanisms to cushion the brute realities of global hierarchy. Unlike the G20 and similar bodies,

they also typically have secretariats with at least the pretense of political independence, staffed by

international civil servants. Related to this question of equity is the challenge of accountability.

Whatever the shortcomings of formal international organizationsand they are legionthey tend to

be more rule-governed and transparent than in their deliberations and decision-making than minilateral coalitions. It is thus easier to hold them to account.

The challenges of global governance are too important to be left to international organizations alone.

But enthusiasm for flexible multilateralism should not blind the United States and other major

governments to the potential risks of overreliance on ad hoc solutions. In the twenty-first century, a

stable, secure, and prosperous world order will rest not only on effective coalitions tailored to

particular exigencies and issues but on revitalized universal institutions grounded in international

law. The trick for the United States and other major governments is to design la carte mechanisms

that complement and reinvigorate, rather than undermine and marginalize, the prix fixe menu of

formal international organizations upon which the world continues to depend.

About author:

Stewart Patrick, Senior Fellow and Director of the Program on International Institutions and

Global Governance, Council on Foreign Relations (Washington, USA).

The author thanks Naomi Egel for editorial assistance.

#22, July 2015

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- South African Foreign Policy Review: Volume 1De la EverandSouth African Foreign Policy Review: Volume 1Încă nu există evaluări

- Amilcar Cabral - Identity and Dignity in The National Liberation StruggleDocument10 paginiAmilcar Cabral - Identity and Dignity in The National Liberation StruggleDurjoy ChoudhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Not Yet Post-Colonial: Essays on Ghetto Being, Cosmology and Space in Post-Imperial ZimbabweDe la EverandNot Yet Post-Colonial: Essays on Ghetto Being, Cosmology and Space in Post-Imperial ZimbabweÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anjali Arondekar: Border/LinesexDocument16 paginiAnjali Arondekar: Border/LinesexAJ LewisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kim Jong Un AphorismsDocument74 paginiKim Jong Un AphorismsStimmeKoreas100% (2)

- Making Africa Work Through the Power of Innovative VolunteerismDe la EverandMaking Africa Work Through the Power of Innovative VolunteerismÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender, Development, and DiversityDocument95 paginiGender, Development, and DiversityOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Queering Archives: A Roundtable DiscussionDocument22 paginiQueering Archives: A Roundtable DiscussionAntonimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workers, Unions, and Global Capitalism: Lessons from IndiaDe la EverandWorkers, Unions, and Global Capitalism: Lessons from IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biafra Separatism Causes Consequences AnDocument70 paginiBiafra Separatism Causes Consequences AnCel BuchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land Dispossession and Everyday Politics in Rural Eastern IndiaDe la EverandLand Dispossession and Everyday Politics in Rural Eastern IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Media and Politics in Africa: Reflections On Free Expression, Social Media and ToleranceDocument58 paginiMedia and Politics in Africa: Reflections On Free Expression, Social Media and ToleranceAfrican Centre for Media Excellence100% (1)

- Empire, Global Coloniality and African SubjectivityDe la EverandEmpire, Global Coloniality and African SubjectivityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Gender Studies in Eastern and Southern AfricaDocument40 paginiIntroduction To Gender Studies in Eastern and Southern AfricaRana Mujtaba Yousaf KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic and Monetary Sovereignty in 21st Century AfricaDe la EverandEconomic and Monetary Sovereignty in 21st Century AfricaMaha Ben GadhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- OADosunmuDissertation ETD 1Document226 paginiOADosunmuDissertation ETD 1Rakeem Por QueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aid and Trade Legacy of ColonialismDocument19 paginiAid and Trade Legacy of ColonialismMohammad MohiuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Declaration AWLN Young Women Leaders CaucusDocument2 paginiFinal Declaration AWLN Young Women Leaders CaucusAfrican Women Leaders Network AWLNÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introducing Marxist EconomicsDocument24 paginiIntroducing Marxist Economicspastetable100% (1)

- 1989 - Contemporary West African States - D.B.C. O'Brien, J. Dunn, R. Rathbone PDFDocument235 pagini1989 - Contemporary West African States - D.B.C. O'Brien, J. Dunn, R. Rathbone PDFRenato AraujoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparatively Queer-Interrogating Identities Across TimeDocument245 paginiComparatively Queer-Interrogating Identities Across TimeJosé LinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Marxist-Feminist Critique of IntersectionalityDocument9 paginiA Marxist-Feminist Critique of IntersectionalityLila LilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Culture of Poverty PDFDocument3 paginiThe Culture of Poverty PDFmonrocha0% (1)

- Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx's Law of Value (Samir Amin)Document205 paginiModern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx's Law of Value (Samir Amin)Jelena ŠipetićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof Wamba-dia-Wamba Public LectureDocument37 paginiProf Wamba-dia-Wamba Public LecturePoqo Aviwe Bulalabathakathi TyumreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni-Coloniality of Power AfricaDocument308 paginiSabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni-Coloniality of Power AfricaZaki100% (1)

- Deported Immigrant Policing Disposable Labor and Global CapitalismDocument316 paginiDeported Immigrant Policing Disposable Labor and Global Capitalismmsadooq0% (1)

- Voices of Hate, Sounds of Hybridity Black Music and The Complexities of RacismDocument24 paginiVoices of Hate, Sounds of Hybridity Black Music and The Complexities of RacismAntonio de OdilonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 UFCW International ConstitutionDocument40 pagini2013 UFCW International ConstitutionLaborUnionNews.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Achille Mbembe - Subject-Subjection - and Subjectivitythesis - Sithole - TDocument450 paginiOn Achille Mbembe - Subject-Subjection - and Subjectivitythesis - Sithole - TJosé Manuel Bueso FernándezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Afterlives of Queer TheoryDocument15 paginiThe Afterlives of Queer Theoryclaudia_mayer_1Încă nu există evaluări

- The Ethics of Peacebuilding (Tim Murithi)Document201 paginiThe Ethics of Peacebuilding (Tim Murithi)Ka Pino100% (1)

- Making Freedom by Anne-Maria MakhuluDocument51 paginiMaking Freedom by Anne-Maria MakhuluDuke University Press50% (2)

- Scheper-Hughes & Bourgois P - Introduction Making Sense of ViolenceDocument32 paginiScheper-Hughes & Bourgois P - Introduction Making Sense of ViolenceCronopio Oliveira100% (1)

- Fraser - After The Family WageDocument29 paginiFraser - After The Family WagedontfollowmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathways and Pitfalls: The International Politics of Lebanon's Energy CrisisDocument20 paginiPathways and Pitfalls: The International Politics of Lebanon's Energy CrisisHoover InstitutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neoliberalism Is A Political Project: An Interview With David HarveyDocument5 paginiNeoliberalism Is A Political Project: An Interview With David HarveySocial Scientists' AssociationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maier, Lebon Eds - Women's Activism in Latin America and The Caribbean. Engendering Social Justice, Democratizing CitizenshipDocument397 paginiMaier, Lebon Eds - Women's Activism in Latin America and The Caribbean. Engendering Social Justice, Democratizing Citizenshipsespinoa100% (1)

- What Is Sex... If Love Is Possible PDFDocument21 paginiWhat Is Sex... If Love Is Possible PDFVolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gramsci's Black MarxDocument17 paginiGramsci's Black MarxL_AlthusserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fugitive Flesh, Gender Self-Determination, Queer Abolition, and Trans Resistance.Document7 paginiFugitive Flesh, Gender Self-Determination, Queer Abolition, and Trans Resistance.Mauricio Albarracín CaballeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- WTP Executive Summary 1.15.14Document5 paginiWTP Executive Summary 1.15.14dmckessoÎncă nu există evaluări

- POP POWER: Pop Diplomacy For A Global SocietyDocument82 paginiPOP POWER: Pop Diplomacy For A Global SocietyLuis Antonio Vidal PérezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ain - T I A Feminist African American Men Speak Out On Fatherhood, Friendship, Forgiveness, and Freedom PDFDocument288 paginiAin - T I A Feminist African American Men Speak Out On Fatherhood, Friendship, Forgiveness, and Freedom PDFValeria LaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender, Development, and MoneyDocument99 paginiGender, Development, and MoneyOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bretton Woods ProceedingsDocument685 paginiBretton Woods ProceedingsgottsundaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chimurenga Chronic New CartographiesDocument100 paginiChimurenga Chronic New CartographiesGabriela Gaia100% (1)

- TRACING FEMINISMS IN BRAZIL: LOCATING GENDER, RACE, AND GLOBAL POWER RELATIONS IN REVISTA ESTUDOS FEMINISTAS PUBLICATIONS - Renata Rodrigues BonettoDocument102 paginiTRACING FEMINISMS IN BRAZIL: LOCATING GENDER, RACE, AND GLOBAL POWER RELATIONS IN REVISTA ESTUDOS FEMINISTAS PUBLICATIONS - Renata Rodrigues BonettoLuiza Rocha RabelloÎncă nu există evaluări

- John L. McKnight - A Guide For Government OfficialDocument3 paginiJohn L. McKnight - A Guide For Government Officialsaufi_mahfuz100% (1)

- Common Sense and CultureDocument17 paginiCommon Sense and CultureRubén AnaníasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond Black and White - Matsuda PDFDocument7 paginiBeyond Black and White - Matsuda PDFAline DolinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Legacy of Sarah Baartman - Natasha Gordon-ChipembereDocument221 paginiThe Legacy of Sarah Baartman - Natasha Gordon-ChipembereDaniel RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diffraction As A Methodology For Feminist Onto Epistemology On Encountering Chantal Chawaf and Posthuman InterpellationDocument15 paginiDiffraction As A Methodology For Feminist Onto Epistemology On Encountering Chantal Chawaf and Posthuman InterpellationcwaranedÎncă nu există evaluări

- NkrumahDocument38 paginiNkrumahShemon Salam100% (1)

- Africa in The World: A History of ExtraversionDocument52 paginiAfrica in The World: A History of ExtraversionStephen Scott100% (2)

- Keywords For Radicals: The Contested Vocabulary of Late Capitalist Struggle - Philosophy of LanguageDocument5 paginiKeywords For Radicals: The Contested Vocabulary of Late Capitalist Struggle - Philosophy of LanguagelucebycuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Nigerian Socialist Movement & The Challenge of Organisation - 7 ThesesDocument39 paginiThe Nigerian Socialist Movement & The Challenge of Organisation - 7 ThesesOsaze Lanre NosazeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa's ResourcesDocument3 paginiAfrica's ResourcesaprilsixÎncă nu există evaluări

- WAR AND PEACE IN THE 21st CENTURY: International Stability and Balance of The New TypeDocument15 paginiWAR AND PEACE IN THE 21st CENTURY: International Stability and Balance of The New TypeValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- ISIS As Portrayed by Foreign Media and Mass CultureDocument23 paginiISIS As Portrayed by Foreign Media and Mass CultureValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regionalisation and Chaos in Interdependent World Global Context by The Beginning of 2016Document13 paginiRegionalisation and Chaos in Interdependent World Global Context by The Beginning of 2016Valdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prospects For Nuclear Power in The Middle East: Russia's InterestsDocument76 paginiProspects For Nuclear Power in The Middle East: Russia's InterestsValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayDocument14 paginiReflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Сentral Аsia: Secular Statehood Challenged by Radical IslamDocument11 paginiСentral Аsia: Secular Statehood Challenged by Radical IslamValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lessons of The Greek TragedyDocument15 paginiLessons of The Greek TragedyValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdai Paper #33: Kissinger's Nightmare: How An Inverted US-China-Russia May Be Game-ChangerDocument10 paginiValdai Paper #33: Kissinger's Nightmare: How An Inverted US-China-Russia May Be Game-ChangerValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- High End Labour: The Foundation of 21st Century Industrial StrategyDocument13 paginiHigh End Labour: The Foundation of 21st Century Industrial StrategyValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeremy Corbyn and The Politics of TranscendenceDocument12 paginiJeremy Corbyn and The Politics of TranscendenceValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdai Paper #36: The Legacy of Statehood and Its Looming Challenges in The Middle East and North AfricaDocument14 paginiValdai Paper #36: The Legacy of Statehood and Its Looming Challenges in The Middle East and North AfricaValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Governance For A World Without World GovernmentDocument11 paginiGovernance For A World Without World GovernmentValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionDocument19 paginiStrategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Valdai Paper #38: The Network and The Role of The StateDocument10 paginiValdai Paper #38: The Network and The Role of The StateValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Background and Prospects of The Evolution of China's Foreign Strategies in The New CenturyDocument15 paginiThe Background and Prospects of The Evolution of China's Foreign Strategies in The New CenturyValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaDocument10 paginiValdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdai Paper #32: The Islamic State: An Alternative Statehood?Document12 paginiValdai Paper #32: The Islamic State: An Alternative Statehood?Valdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Сivil Society in Conflicts: From Escalation to MilitarizationDocument13 paginiСivil Society in Conflicts: From Escalation to MilitarizationValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Prospects of International Economic Order in Asia Pacific: Japan's PerspectiveDocument9 paginiThe Prospects of International Economic Order in Asia Pacific: Japan's PerspectiveValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityDocument12 paginiGeopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discipline and Punish Again? Another Edition of Police State or Back To The Middle AgesDocument10 paginiDiscipline and Punish Again? Another Edition of Police State or Back To The Middle AgesValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Document12 paginiValdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Valdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Agenda For The EEU EconomyDocument15 paginiAgenda For The EEU EconomyValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Just War and Humanitarian InterventionDocument12 paginiJust War and Humanitarian InterventionValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- After American Hegemony and Before Global Climate Change: The Future of StatesDocument9 paginiAfter American Hegemony and Before Global Climate Change: The Future of StatesValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Future of The Global Trading SystemDocument8 paginiThe Future of The Global Trading SystemValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in The WestDocument8 paginiThe Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in The WestValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Commons: A New Alternative To NeoliberalismDocument8 paginiSocial Commons: A New Alternative To NeoliberalismValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Reviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismDocument7 paginiReviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismValdai Discussion ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09-Nicolas v. Romulo G.R. No. 175888 February 11, 2009Document27 pagini09-Nicolas v. Romulo G.R. No. 175888 February 11, 2009Jopan SJ100% (1)

- Clinton - Bosnia BookletDocument58 paginiClinton - Bosnia Bookletveca123100% (1)

- Ghost of Rwanda ReflectionDocument2 paginiGhost of Rwanda Reflectionaquanesse21Încă nu există evaluări

- Terrorism and International Humanitarian LawDocument91 paginiTerrorism and International Humanitarian LawRaHul AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1647524021faculty of Social Sciences Mid Term Date Sheet Spring 2022Document20 pagini1647524021faculty of Social Sciences Mid Term Date Sheet Spring 2022Shamshad Ali RahoojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft Invitation & Rekomendation Letter Utk KBRI TokyoDocument3 paginiDraft Invitation & Rekomendation Letter Utk KBRI TokyoVina KusumaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Refugee Concept Under International LawDocument4 paginiThe Refugee Concept Under International LawAditi BhawsarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Napoleon Bonaparte NotesDocument4 paginiNapoleon Bonaparte Notesapi-507047686Încă nu există evaluări

- MoonDocument5 paginiMoonSelman Hayder AbbasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russian Delegate's Position PaperDocument4 paginiRussian Delegate's Position PaperSiddharth Sourav100% (1)

- Gcworld L1: Market IntegrationDocument6 paginiGcworld L1: Market Integrationshaina juatonÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Position PaperDocument3 paginiHow To Write A Position PaperAndrés MatallanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public International Law Reviewer - CruzDocument48 paginiPublic International Law Reviewer - CruzMai Reamico100% (10)

- The Good Friday AgreementDocument2 paginiThe Good Friday AgreementDeniseFrăţilăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Droit International.' That Review AddressesDocument2 paginiDroit International.' That Review AddressesMogsy PernezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay Decolonisation International InfluenceDocument7 paginiEssay Decolonisation International InfluenceClive GilbertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apparel Imports USDocument9 paginiApparel Imports USTarek OsmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is It Worth To Rescue The Doha Round (Reading Response)Document1 paginăIs It Worth To Rescue The Doha Round (Reading Response)Treblif AdarojemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Feature - The Evolution of The Nation-State: Written by Erik RingmarDocument3 paginiStudent Feature - The Evolution of The Nation-State: Written by Erik RingmarEHSAN ALIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Development After World War IIDocument10 paginiEconomic Development After World War IIhira khalid kareemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Response From President Juncker and President Tusk To The Prime MinisterDocument5 paginiResponse From President Juncker and President Tusk To The Prime MinisterThe GuardianÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASSIGNMENT 3 (EA) - Gabatan, Heavenly T.Document3 paginiASSIGNMENT 3 (EA) - Gabatan, Heavenly T.Artemio Entendez IIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Government: Basic Forms of GovernmentDocument6 paginiGovernment: Basic Forms of Governmentsuruth242Încă nu există evaluări

- French Nuclear DoctrineDocument41 paginiFrench Nuclear Doctrinegatty ipÎncă nu există evaluări

- विश्व के प्रमुख संगठनDocument8 paginiविश्व के प्रमुख संगठनPradhuman Singh RathoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- API BX - Klt.dinv - CD.WD Ds2 en Excel v2 5872141Document74 paginiAPI BX - Klt.dinv - CD.WD Ds2 en Excel v2 5872141Mihalciuc VladÎncă nu există evaluări

- Citizenship For COTDocument44 paginiCitizenship For COTlily mar vinluanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scott Burchill - National Interest in IR TheoryDocument33 paginiScott Burchill - National Interest in IR TheoryshaviraÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 8 Learning Guide With AnswersDocument27 paginiCH 8 Learning Guide With AnswersCarsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- First World WarDocument47 paginiFirst World WarMadalina Bivolaru100% (3)

- Cry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskDe la EverandCry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (6)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaDe la EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (23)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyDe la EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (7)

- The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerDe la EverandThe Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (14)

- The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerDe la EverandThe Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (47)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarDe la EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (4)

- New Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestDe la EverandNew Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsDe la EverandThe Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Blood Brothers: The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in IsraelDe la EverandBlood Brothers: The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in IsraelEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (57)

- Human Intelligence Collector OperationsDe la EverandHuman Intelligence Collector OperationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary: The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization By Peter Zeihan: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization By Peter Zeihan: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern WarDe la EverandThe Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern WarEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)

- Never Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveDe la EverandNever Give an Inch: Fighting for the America I LoveEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (10)

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyDe la EverandThe Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (13)

- International Relations: A Very Short IntroductionDe la EverandInternational Relations: A Very Short IntroductionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (5)

- The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarDe la EverandThe Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (41)

- Conflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineDe la EverandConflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonDe la EverandHow Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (39)

- Palestine Peace Not Apartheid: Peace Not ApartheidDe la EverandPalestine Peace Not Apartheid: Peace Not ApartheidEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (197)

- The Secret War Against the Jews: How Western Espionage Betrayed The Jewish PeopleDe la EverandThe Secret War Against the Jews: How Western Espionage Betrayed The Jewish PeopleEvaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (8)

- The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital AgeDe la EverandThe New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital AgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United StatesDe la EverandTreacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United StatesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

- Can We Talk About Israel?: A Guide for the Curious, Confused, and ConflictedDe la EverandCan We Talk About Israel?: A Guide for the Curious, Confused, and ConflictedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (5)

- War and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945De la EverandWar and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (4)

- Dangerous Decade: Taiwan’s Security and Crisis ManagementDe la EverandDangerous Decade: Taiwan’s Security and Crisis ManagementEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Epicenter: Why the Current Rumblings in the Middle East Will Change Your FutureDe la EverandEpicenter: Why the Current Rumblings in the Middle East Will Change Your FutureEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (22)

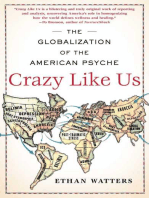

- Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American PsycheDe la EverandCrazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American PsycheEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (16)