Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of Profanity

Încărcat de

Girish KumarDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of Profanity

Încărcat de

Girish KumarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sex Roles, Vol. 12, Nos.

3/4, 1985

Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions

of Profanity

Gary W. Selnow 1

Virginia Teeh

This study examined sex differences in perceptions and uses o f profanity.

Profanity is considered in terms o f the strength it may impart to language

and as a tool Of group cohesion and nonmember alienation. Imp#cations

o f these characteristics are explored in terms o f observed sex differences on

profanity measures. Females reported less profanity usage than males reported,

and females further provided more conservative assessments o f the appropriateness o f profanity usage in various settings. Males more than females reported that profanity provides a demonstration o f social power and serves to

make the user socially acceptable.

Profane words play a peculiar role in the language. Depending on the context of use, they may serve to provide linguistic bonding among interactants

while coincidentally functioning to alienate others from group membership.

Their use may contribute to the establishment of dominant and submissive

roles in a relationship and, in some environments, may furnish a medium

through which a hierarchy among interactants is established_ Language, it

is argued, serves the reciprocal role of reflecting shifts in society while simultaneously contributing to the character of that society. We look to language

as an indicator of deeper currents and we suspect that its use has something

to do with maintaining patterns evident in society and bringing about change.

This paper looks at profanity as a source of communication power and control and, in this context, considers the implications of usage differences between the sexes.

tTo whom correspondence should be addressed at Department of Communications Studies,

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 24084.

303

0360-0025/85/0200-03e13504.50/0 ,~ 1985 Plenum Publishing Corpora6on

304

Selnow

SEX DIFFERENCES IN L A N G U A G E USE

Over the years scholars have reported a variety of language differences

between the sexes_ One of the earliest writers on the topic, Otto Jesperson,

wrote in 1922 that, among other dimensions, women's language differs from

that of men in the selection of vocabulary and formation of sentence structure. Men swear more, use more slang and coarse language, and are disposed

more to build puns into their speech. In contrast, he claimed that women

avoid "rough" language, use a greater number of euphemisms, and generally have a more limited vocabulary (Jespersen, 1922). In terms of sentence

structure, men develop mere complicated sentences involving imbedded

clauses. W o m e n construct sentences Jespersen described as "a string of

pearls," where thoughts are linked one after the other by conjunctions. He attributed these language differences to the "superior. readiness of the speech

of women," which he described as a female predilection to talk as soon as

she has formed a thought (Jespersen, 1922).

In more recent times Jesperson's opinion-based descriptive method has

been joined by two additional approaches to understanding language differences between the sexes. In this literature review three sources of hypotheses

on sex differences in language usage are considered: (1) opinions of scholars

based on logic and reason, (2) empirical research based on subjects' perceptions of male and female language characteristics (stereotypes), and (3) empirical research on actual male and female language samples. While each

successive approach generally represents a higher level of rigor in analysis,

as this review demonstrates, all three contribute to an understanding of language differences.

In a study of language use stereotypes, Kramer (1974) found that subjects of both sexes who were asked to identify cartoon captions as products

of a male or female speaker characterized women's speech according to the

stereotypes of "stupid, vague, emotional, confused and wordy" (Kramer,

1975). Male speech, on the other hand, was identified by Kramer's subjects

to be logical, concise, businesslike, and in control. Kramer argues that what

people believe about sex differences in language may be as important as any

real differences which may exist. In a content analysis of actual language

samples Gleser et al. (1959) found that females used a greater number of

words implying emotion and feeling, while males selected words relating to

time, space, quantity, and destructive action. Other studies, also based on

actual language samples, have similarly discovered that women's speech appears to contain a greater emotional component (Wood, 1966; Barron, 1971).

Based on a review of published research, case studies, and general observations, Bernard (1972), too, recognized emotional features of language used

by women and, in a portion of her book, reviews the nature of these features (see Bernard, 1972, Chap. 6).

Sex Differences in Profanity

305

Other characteristics ascribed to women's language have been noted in

a variety of writings and studies. L a k o f f (1973) writes that women have been

taught to avoid a forceful language style and have been trained instead to

adopt a more polite form of speech. In a comparative analysis of observed

male and female intonation patterns, Brend describes samples of women's

language as displaying a "polite, cheerful" pattern (1975). Barron's research

with actual language samples (1971) revealed that language used by women

appears to be more "person oriented" rather than '"thing oriented" as in male

usage. Similarly, Warshay (1972) found in a content analysis of subjects' writing samples that males refer more often to events, while females more often

reference other people.

Hass (1981) recorded conversations among young children (4, 8, and

12 years) and found in a content analysis of transcripts clear sex differences

in topic selection and style of interaction. In same-sex dyads, males discussed

sports and location; females talked about school, identity, wishing, and needing. In cross-sex interactions, males made a greater number of direct requests

and used a greater number of sound effects (Hass, 1981).

With the research questions posed for this study, there is special concern for the control function of speech. On this topic Chesler (1971) writes

that, through language, males more often direct a communication interaction. This claim was tested in two empirical studies, each based on taped

conversations of cross-sex interactions (Zimmerman & West, 1975; West,

1979). Both studies reported that males were far more likely to interrupt

females than females were to interrupt males. In the Z i m m e r m a n and West

study females were never seen to protest the male's interruption. Clearly here

males dominated the conversations. In West's study, however, where males

again were seen to interrupt females at a greater frequency, male domination of the conversation appeared somewhat attenuated by females' protests

of the interruptions,

In another manifestation of what may be a more complaint female language style, L a k o f f (1973) writes that where men more often use direct questions in speech, women more often provide tag questions demonstrating

greater timidity and uncertainty. It should be noted that there is a good deal

of disagreement on this point. Dubois and Crouch (1975), for instance, argue logically that tag questions may tell little about the security of the speaker.

They additionally report a study in which they collected actual male and female language samples and found no evidence that females had a greater

propensity to use tag questions. In fact, in this sample, tag questions were

spoken only by males.

Of these and a variety of other language differences reported in the

literature, it is, perhaps, the use of "'strong" language which marks the most

obvious differences between male and female speech patterns. Such differences were evident in the early works of Jespersen (1922), who claimed, based

306

Selnow

on his general observations, that women of his day did not swear as much

as men nor did they use as much slang. Several contemporary writings add

to these early observations. In a study involving subject perceptions of language use stereotypes, Kramer (1975) found that respondents in her sample

perceived women's speech to be weaker and to incorporate fewer exclamations and curse words. Evidence here suggests at least a perception of less

forceful language use by women. L a k o f f (1973) characterizes the stereotypical uses of strong language with examples of expletives she claims are typically used by females ("oh dear," "goodness," and "oh, fudge") and male

("shit," "damn"). She logically argues that relative forcefulness of these expletives may be a function of "how strong one allows oneself to feel about

something, so that the strength of an emotion conveyed in a sentence corresponds to the strength of the particle" (Lakoff, 1975, p. 10). Consequently, it is argued, stronger and more forceful statements made by men tend

to reinforce their position of strength.

A handful of empirical studies has explored sex differences in listener

perceptions of speakers who use profanity. Cohen and Saine (1977) found

that listener evaluation scores for speakers who use profanity were poorer

for same-sex persons than opposite-sex persons. In an explanation of this

finding they suggest that recent attention to sex roles may have resulted in

people being more critical of same-sex behavior and more accepting of

opposite-sex behavior. A second study, in which taped presentations of speakers who used profanity were evaluated by male and female listeners, failed

to find any rating differences at all. Females and males provided no significant differences in their scores for either female or male speakers. Mulac

notes that such a finding may be explained by "shifting beliefs regarding appropriate behavior for males and females" (Mulac, 1976, p. 307).

The questions posited for this study deal primarily with sex differences

in the usage and perceptions of profanity. Underlying these discussions,

however, are two issues which stand as important items of debate. Some

writers contend that male speech (characterized, in part, by its profanity content) facilitates male ties, and swearing, furthermore, functions to exclude

females from traditionally male settings (e.g., Thorne & Henley, 1975). A

second issue deals with the notion that "strong" language used by males contributes to the maintenance of male domination in mixed-sex interactions

(e.g., Lakoff, 1973). These two positions are considered in the findings of

this research.

Five questions guide this study:

1.

2.

Is there a measurable sex difference in the reported frequency of

profanity use?

Are there sex differences in respondent assessments of when profanity use is and is not appropriate?

Sex Differences in Profanily

3.

4.

5.

307

Are there sex differences in the reported perceptions of the role

profanity plays in language?

Are there sex differences in respondent background characteristics

which may have an effect on the uses and perceptions of profanity?

Are there sex differences in respondent ratings of profane words?

METHOD

The sample consisted of 135 undergraduate students (61 females and

74 males) representing a fairly heterogeneous mix of academic majors and

class years. Most of the respondents were raised in the eastern United States;

hometowns of this sample were fairly well spread along a rural-urban continuum.

Each respondent completed a questionnaire which requested information about hometown setting, family demographics, religious orinetations,

church attendance, media consumption patterns, and other details about daily

habits.

Respondents were asked to use a four-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely,

3 = occasionally, 4 = frequently) to assess their own use of profanity in

everyday conversations and the use of profanity by friends. They were then

given a list of social and media conditions and asked to indicate how strongly they agreed/disagreed that it was all right to use profanity in these instances

(1 = strongly agree, 6 = strongly disagree). For instance, they were asked

to record their level of agreement with the proposition that it was all right

to use profanity in formal meetings, in newspaper stories, on Saturday morning television, etc.

Subjects were asked finally to evaluate the degree of obscenity for 16

items on a list of profane words using a six-point scale (1 = not obscene,

6 = very obscene). These words were extracted from lists developed by Cameron (1970). For analytic purposes the words were clustered into categories

(sexual, religious, excretory) also suggested by Cameron.

RESULTS

1. Frequency of Profanity Use/2. Appropriateness of Use

The initial series of questions sought to obtain a self-reported estimate of

the frequency with which respondents used profanity in daily speech. On this

measure female respondents reported significantly less use of profanity (X =

2.38) than reported by males (X = 2.85) (t = 2.09, df = 115, p < .03). This

308

Selnow

o b s e r v a t i o n takes on a d d e d strength in light o f o t h e r measures r e c o r d e d for

this sample.

R e s p o n d e n t s also were asked to r e p o r t how a p p r o p r i a t e they felt it

would be to use p r o f a n i t y in various circumstances. In all b u t a single instance (the use o f p r o f a n i t y in m i x e d c o m p a n y - - t h e difference was not significant), female r e s p o n d e n t s said that they felt the use o f p r o f a n i t y w o u l d

be less a p p r o p r i a t e than males said it w o u l d be. Significant differences were

f o u n d for the use o f p r o f a n i t y in f o r m a l meetings (males, X = 5.30; females,

X = 5.73; t = 3.09, d f --- 109, p < .003). N o t e t h a t higher means indicate

less a g r e e m e n t with the a p p r o p r i a t e n e s s o f p r o f a n i t y usage on television after 11 P M (males, X 3.26; females, X = 3.83; t = 2.90, d f = 126, p

< _04), on S a t u r d a y m o r n i n g television (males, X = 5.48; females, X =

5.93; t = 3.23, df = 93, p < .002), on cable television (males, X = 2.98;

females, X = 3.75; t = 2.70, df = 123, p < .008), and in newspapers (males, X

= 4.35; females, X = 5.08; t = 2.90, d f = 131, p < .003). In an index

c o m p r i s e d o f all items dealing with the suitability o f p r o f a n i t y use, we f o u n d

that females were significantly less likely t h a n males to r e p o r t that p r o f a n i t y

use w o u l d be a p p r o p r i a t e (males, X = 4.11; females, X = 4.50; t = 2.36,

d f = 124, p < .02).

3. Perceptions of the Role of Profanity in Language

The next series of items sought to determine if there were sex differences in the p e r c e p t i o n s o f how p r o f a n i t y served the user. In this review we

discovered two distinctions. First (using a six-point scale: 1 = strongly agree,

6 = strongly disagree), while all r e s p o n d e n t s disagreed with the p r o p o s i t i o n

that "the use o f p r o f a n i t y serves to d e m o n s t r a t e social p o w e r , " males ( X =

4.60) disagreed less s t r o n g l y t h a n females ( X = 5.22) (t = 2.85, d f = 131,

p < .005). Second, although both males and females disagreed with the statem e n t that "the use o f p r o f a n i t y helps to m a k e one socially acceptable," males

(X = 4,43) were again less c o m m i t t e d in their d i s a g r e e m e n t t h a n females

(X = 4,91) (t = 2.07, df = 131, p < .04). The significance of these findings can best be realized in light o f previous a r g u m e n t s which c o n t e n d that

p r o f a n i t y usage c o n t r i b u t e s to the d o m i n a n c e o f the user a n d that it serves

the dual f u n c t i o n o f g r o u p cohesion a n d a l i e n a t i o n o f nonusers.

4. Background Characteristics

In o r d e r to isolate factors which m a y a c c o u n t for differences between

the sexes in the uses a n d p e r c e p t i o n s o f p r o f a n i t y , we explored several issues

related to family b a c k g r o u n d and life-style characteristics of the respondent.

Sex Differences in Profanily

309

Based in part on sociolinguistic theories which postulate a relationship

between the child's use of language and her/his home language environment,

we sought to uncover differences in respondent recall of profanity usage in

the home. We found no significant differences between males and females

in reports of sibling profanity use. Furthermore, our data show no sex differences in reports of profanity use by the father. [We did, however, discover

that both sexes reported that the father used significantly more profanity

(X = 2.14) than the mother used in the home (X = 1.58) (t = 5.65, df =

127, p < .001)]. The most noteworthy observation in this series identified

a sex difference in reports of the mother's profanity usage. Female respondents' reports of their mother's use of profanity (X = 1.79) were significantly higher than those of males (X = 1_30).

5. Obscenity Ratings of Profane Words

In order to provide a measure of the perceived intensity of profane

words, respondents were asked to rate 16 commonly used terms on a sixpoint scale. We logically assumed that females, who reportedly used these words

less frequently than males and found them less appropriate in a variety of

social, business, and media settings, would rate the words more harshly. Our

assumption generally was not confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Previous writings have staked out the issues concerning language style

and its implications for perceptions of the user and the establishment of user

dominance in social interactions. They have also discussed broader sociological issues concerning the relationships of sex-role stereotypes and language features, and group maintenance/nonmember alienation. The objectives

of the present study deal only indirectly with such discussions, concentrating instead on several component arguments which feed into this general dialogue.

If there is a "bottom line" to findings of this research it must be that,

indeed, there are sex differences in the reported uses and perceptions of profanity. Women claim to incorporate profanity less frequently into their speech

and also express a relatively more negative impression of profanity use on

a wide variety of measures. Compared to male respondents, women report

a greater disapproval of profanity use on television and in formal settings.

Inasmuch as profanity use may contribute to the perceived "strength"

of language, these measures, taken in aggregate, suggest that there are differences on this dimension between the language used by men and that used

by women. While there are no comparable historical data with which to corn-

310

Selnow

pare these findings, we can report only that, given the limitations of this study,

it appears that there are presently some sex differences in the perceived capacity of profanity to impart strength to language.

In our exploration of background variables we turned up several items

worth attention. We discovered that both sexes report a significantly greater

frequency of profanity use by the father than the mother. In addition to confirming an intuitive suspicion, it also provides yet another confirmation of

profanity use differences between the sexes: males (fathers) are reported to

use more profanity, at least in the home environment, than are females

(mothers). In terms of sex differences in perceptions of profanity use by parents we observed that while no sex differences were recorded for the father's

use of profanity at home, there was a curious difference between male and

female recall of the mother's profanity use. Women in our sample, compared

to the men, claimed that their mothers used profanity more frequently. Could

it be that mothers were more inclined to use profanity around their daughters than around their sons? Perhaps the image of mothers retained by sons

does not conveniently include the vision of a woman who uses profanity.

Perhaps assimilated into responses of sons is the essence of a cultural stereotype that maintains that "good girls don't use bad words" (and certainly my

mother is a good girl).

It made good sense to expect that people who choose to use profanity

less frequently and believe that its use is often out of place will be likely to

provide relatively more severe obscenity ratings for these words. As we noted earlier, for two of three categories, female respondents rated profane words

to be no less obscene than did male respondents. More surprising, however,

was the discovery that while women rated excretory and sexual profanities

about the same as men did, it was men who rated religious profanities most

severely.

The findings for sexual profanities was not expected, and in the absence of additional data, an explanation remains no more than conjecture.

We may begin, however, with the observation that, of the three categories

of profanity, sexual words were rated most harshly by respondents of both

sexes [index of excretory and religious profanities (X = 2.78) compared to sexual profanities (X = 3.84) (t = 15.8, df = 119, p < .001)]. This finding conforms to previous observations by Cameron (1970) and Baudhuin (1973).

On the basis of arguments presented by several recent writers, we would

predict females to be significantly more critical of sexual profanities. At the

core of this position is the very nature of sexual profanities, which express

the anatomical differences between the sexes and characterize male-female

relationship in the sex act. Lawrence (1974) contends that implicit in many

sexual profanities is the systematic derogation of women. She claims that

many of the sexual terms evoke an image which is "undeniably painful,

Sex Differences in Profanily

311

if not sadistic, (in its) implications, the object of which is almost always female" (Lawrence, 1974, p. 33). If Lawrence's position is c o r r e c t - i f women

are conscious of the proposed sadistic implications of sexual terms and are

consequently more offended by such t e r m s - w e would expect females to be

more severe critics of sexual profanities. Our findings clearly do not lend

support to such a proposition.

We did record a significant sex difference in religious profanity, though,

where males provided significantly more severe ratings than females of words

such as "damn," "goddamned," and "hell." Males and females, in our sample, report about the same religious intensity and church attendance. We,

therefore, cannot conveniently attribute sex differences to fundamental religious orientations. This is a curious finding that cannot be explained readily

by the available data.

As we suggested earlier, the immediate issues of concern to sex differences in perceptions and uses of profanity are the functions of profanity in

group maintenance (and exclusion of group nonmembers) and the establishment of male dominance in mixed-sex interactions. While all of the findings

reported here have some implications for these issues, two observations stand

as particularly relevant. In our review of the value of profanity to the speaker, we noted the following:

males were less likely to reject the proposition that profanity helps make

one socially acceptable; and

males were less likely to reject the statement that the use of profanity

serves to demonstrate the social power of the user.

If males do, in fact, see the use of profanity as a tool with which to

bring about social acceptance, they may be inclined to use profanity themselves (to enhance their own social acceptance) and to view with favor others

who also use profanity. This suggests that profanity usage may serve at least

some role in the group maintenance process. Participants in informal groups

may be granted admittance and be allowed to sustain their membership, in

part, because of this linguistic "ticket." It follows then (on this issue alone)

that females who use profanity less frequently may not meet this expectation of group membership. Findings here suggest that in terms of the issues

described by Thorne and Henley (1975), swearing, indeed, may serve to exclude females from traditionally male settings.

In the context of mixed-sex interactions Lakoff proposes that "strong language" serves to establish the dominance of the user and that males, who

are relatively more frequent users of strong language, emerge more often

as dominant in these settings. Based on this argument alone our findings suggest that males, who we found to be more prolific users of profanity, may

stand to be the dominant interactant in a mixed-sex interaction. Our investigation proceeds a step beyond this, however, with the observation that males

312

Selnow

are more inclined to perceive the use of profanity as a demonstration of social power. This suggests that they may u s e profanity (in addition to other

elements-interruptions, volume, etc.) to help achieve dominance.

REFERENCES

Barron, N. Sex-typed language: The production of grammatical cases. Acta Sociologica, 1971,

14(1, 2), 24-72.

Bauduin, F. Obscene language and evaluative response: An empirical study. Psychological

Reports, 1973, 32, 399-402.

Bernard, J. The sex game. New York: Atheneum, 1972.

Brend, R. Male-female intonation patterns in American English. In B. Thorne & N. Henley

(Eds.), Language and sex: Difference and dominance. Rowley, MA: Newbury House,

1975, pp.84-87.

Cameron, P. Frequency and kinds of words in various social settings, or what the hell's going

on? Pacific Sociological Revzew, 1969, 12, 101-104.

Cameron, P. The words college students use and what they talk about. Journal of Communication Disorders, 1970, 32, 36-46.

Cohen, M., & Saine, T. The role of profanity and sex variables in interpersonal impression

formation. Journal o f Applied Communication Research, 1977, 2(5), 45-52.

Chesler, P. Marriage and psychotherapy. In the Radical Therapist Collective (Eds.), The radical Therapist. New York: Ballantine, 1971, pp. 175-180_

Gleser, G,, Gottscbalk, L., & Watkins, J. The relationship of sex and intelligence to choice

of words: A normative study of verbal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1959,

15, 182-191.

Haas, A. Partner influences on sex associated spoken language of children. Sex Roles, 1981,

7(9), 925-935.

Jay, T. A frequency count of college and elementary school students' colloquial English. Catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology, 1981, 10, 1.

Kramer, C. Folklinguistics. Psychology Today, 1974, 8, 82-85.

Kramer, C Womens' speech: Separate but unequal? In B. Thorne & N. Henley (Eds.), Language and sex: Difference and dominance. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975.

Lakoff, R. Language and woman's place. Language in society, 1973, 2, 45-49.

Lakoff, R. Language and woman's place. New York: Harper and Row, 1975.

Lawrence, B. Dirty words can harm you. Redboolc, 1974, 143, 33.

Mabry, E. Dimensions of profanity. Psychological Reports, 1974, 35(1, pt. 2), 387-391.

Markel, N., Prebor, L., & Brandt, J. Bio-social factors in dyadic communication: Sex and speaking intensity_ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1972, 23, 11-13.

Mulac, A. Effects of obscene language upon three dimensions of listener attitude. Communication Monographs, 1976, 43(4), 300-307.

Sanders, J., & Robinson, W. Talking and not talking about sex: Male and female vocabularies.

Journal of Communication, 1979, 29(2), 22-30.

Thorne, B., & Henley, N. Difference and dominance: An overview of language, gender and

society. In B. Throne & N. Henley (Eds.), Language and sex: Difference and dominance.

Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975, pp. 5-42.

Warshay, D. Sex differences in language style. In C. Safilios-Rothschild (Ed.), Toward a sociology o f women. Lexington, MA: Xerox, 1972, pp. 3-9.

West, C. Against our will: Male interruptions of females in cross-sex conversations. Annals of

the New Yor# Academy of Sciences, 1979, 327, 81-97.

Wood, M. The influence of sex and knowledge of communication effectiveness on spontaneous speech. Word, 1966, 22(1-3), 112-137.

Zimmerman, D., & West, C. Sex roles, interruptions and silences in conversation. In B. Thorne

& N. Henley (Eds.), Language and sex: Difference and dominance. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975, pp. 105-129.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Biblical Philosophy of Leadership with Special Reference to DeuteronomyDe la EverandBiblical Philosophy of Leadership with Special Reference to DeuteronomyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selnow 1985, Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of ProfanityDocument10 paginiSelnow 1985, Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of ProfanityLuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion CommunicationDe la EverandKinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion CommunicationEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- Language and Gender.A Literature ReviewsDocument4 paginiLanguage and Gender.A Literature ReviewsTerizla MobileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lewis Henry Morgan's Comparisons: Reassessing Terminology, Anarchy and Worldview in Indigenous Societies of America, Australia and Highland Middle IndiaDe la EverandLewis Henry Morgan's Comparisons: Reassessing Terminology, Anarchy and Worldview in Indigenous Societies of America, Australia and Highland Middle IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Gender StudiesDocument5 paginiIntroduction To Gender StudiesAQSA JAMEELÎncă nu există evaluări

- Folk Linguistics, Epistemology, and Language TheoriesDe la EverandFolk Linguistics, Epistemology, and Language TheoriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donna M. Johnson and Duane H. Roen: Complimenting and Involvement in Peer Reviews: Gender VariationDocument31 paginiDonna M. Johnson and Duane H. Roen: Complimenting and Involvement in Peer Reviews: Gender VariationTuğberkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and GenderDocument11 paginiLanguage and GenderAna-maria CojocaruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Differences in The Use of Intensifiers: Narges SardabiDocument11 paginiGender Differences in The Use of Intensifiers: Narges SardabiManar El-khatibÎncă nu există evaluări

- TPLS, 03Document6 paginiTPLS, 03huyenthu2902Încă nu există evaluări

- Language and Gender: SociolinguisticsDocument10 paginiLanguage and Gender: SociolinguisticsArianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and Gender, Reading MaterialDocument6 paginiLanguage and Gender, Reading MaterialtechnicanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deficit Approach: Limitations in Jesperson's WorkDocument4 paginiDeficit Approach: Limitations in Jesperson's WorkFaiza Sajid100% (1)

- Rubaiya Chowdhury 56612 Eng234 Final Research PaperDocument13 paginiRubaiya Chowdhury 56612 Eng234 Final Research PaperRubaiya ChowdhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women's Language Features Found in Same-Sex and Cross-Sex Conversations in He's Just Not That Into You MovieDocument10 paginiWomen's Language Features Found in Same-Sex and Cross-Sex Conversations in He's Just Not That Into You MovieArsya Nararya PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- GROUP 3 - Language and GenderDocument11 paginiGROUP 3 - Language and GenderArianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Scientific Journal Vol. 9 No.2Document9 paginiEuropean Scientific Journal Vol. 9 No.2Europe Scientific JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Diffeerences in Language UsesDocument27 paginiGender Diffeerences in Language UsesGuilherme Basso Dos ReisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationship Between Language Gender LearnersDocument8 paginiRelationship Between Language Gender LearnersKaleem KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Important Strand of Language and Gender Research Has Focused OnDocument4 paginiAn Important Strand of Language and Gender Research Has Focused OnBettiche SamahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and Gender EssayDocument8 paginiLanguage and Gender EssayOmabuwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and GenderDocument10 paginiLanguage and GenderRosita PeraltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7Document67 paginiChapter 7Eliza Mae OcateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language & GenderDocument23 paginiLanguage & Genderanushaymetla100% (4)

- International Journal of English Language and Literature StudiesDocument9 paginiInternational Journal of English Language and Literature StudiesZara NurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of Language and GenderDocument3 paginiTheories of Language and GenderRisma Dwi AryantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and GenderDocument8 paginiLanguage and GenderLusy MkrtchyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociolinguistics and Women's LanguageDocument6 paginiSociolinguistics and Women's LanguageAJHSSR JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gendered Language in InteractiDocument18 paginiGendered Language in InteractiEdzkie Nicolas AlingasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- And Women Are From Venus, That Males and Females Oftentimes Clash When Communicating Because When TheyDocument4 paginiAnd Women Are From Venus, That Males and Females Oftentimes Clash When Communicating Because When TheyWelmar MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Materi Lengkap LANGUAGE AND GENDERDocument4 paginiMateri Lengkap LANGUAGE AND GENDERm dÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gendered Representations Through Speech: The Case of The Harry Potter SeriesDocument20 paginiGendered Representations Through Speech: The Case of The Harry Potter SeriesFelipe CamargosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Differences in Translating Jane Austen-S Pride and Prejudice - The Greek Paradigm PDFDocument13 paginiGender Differences in Translating Jane Austen-S Pride and Prejudice - The Greek Paradigm PDFnycÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Lius Bahan ProposalDocument37 paginiNo Lius Bahan Proposallius8927Încă nu există evaluări

- Genderlect EHTDocument4 paginiGenderlect EHTAbraham Adejare AdekunleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Discourse Analysis: Communicative Strategies and Cultural InfluencesDocument2 paginiGender Discourse Analysis: Communicative Strategies and Cultural InfluencesdjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Differences in Language UseDocument7 paginiGender Differences in Language UseSabahat BatoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Background of StudyDocument3 paginiBackground of Studyduchess.essienÎncă nu există evaluări

- Differences Between Male and Female in The Argumentative WrittingDocument33 paginiDifferences Between Male and Female in The Argumentative WrittingLeo GaetanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Influence in Languge UseDocument9 paginiGender Influence in Languge UsePolina BedaravaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment No.02Document7 paginiAssignment No.02Maryam FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language of Homosexuality ABRENICADocument25 paginiLanguage of Homosexuality ABRENICAJOSEPERCIVAL DANTESÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Use of Lexical Hedges in Spoken EnglishDocument11 paginiThe Use of Lexical Hedges in Spoken EnglishGrace Irene Mutiara100% (1)

- Hall 2020 Language and GenderDocument22 paginiHall 2020 Language and GenderSam LongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lexical Analysis of Gender and Language TheoriesDocument12 paginiLexical Analysis of Gender and Language TheoriesBojana Savic100% (2)

- A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Swear Word Offensiveness PDFDocument24 paginiA Sociolinguistic Analysis of Swear Word Offensiveness PDFtanjasamja100% (1)

- Contoh Tema 2Document15 paginiContoh Tema 2Kiyowo MenyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2007 Hunter-Smith Sarah PDFDocument58 pagini2007 Hunter-Smith Sarah PDFRand AlashqerÎncă nu există evaluări

- (2004) Pierrehumbert Et Al. - The Influence of Sexual Orientation On Vowel ProduDocument4 pagini(2004) Pierrehumbert Et Al. - The Influence of Sexual Orientation On Vowel Produmiguel.jimenez.bravoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faculty Foreign Languages and Cross-Cultural CommunicationDocument24 paginiFaculty Foreign Languages and Cross-Cultural CommunicationАнастасия КравченкоÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language and GenderDocument24 paginiLanguage and Gendergotengohan73Încă nu există evaluări

- IJLL - Grammatical Gender - Michael KatzDocument8 paginiIJLL - Grammatical Gender - Michael Katziaset123Încă nu există evaluări

- Language in SocietyDocument16 paginiLanguage in Societyrise elvindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Influence of Gender in Politeness Strategy Used in "Keeping Up With The Kardashians"Document6 paginiThe Influence of Gender in Politeness Strategy Used in "Keeping Up With The Kardashians"International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Inequalities in Common English Utterances.Document12 paginiGender Inequalities in Common English Utterances.Jatin ChauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- He's A Man and She's A Woman: A Conversation Analysis On Linguistic Gender DifferencesDocument5 paginiHe's A Man and She's A Woman: A Conversation Analysis On Linguistic Gender DifferencesIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scott F. Kiesling, 2019. Language, Gender and Sexuality An Introduction.Document5 paginiScott F. Kiesling, 2019. Language, Gender and Sexuality An Introduction.Christine Iñez Aquino PadlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender-Related Conversation Analysis: ND NDDocument5 paginiGender-Related Conversation Analysis: ND NDAlessa DodiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phillips Borodistky 2003 Replication Spring 2022Document19 paginiPhillips Borodistky 2003 Replication Spring 2022httÎncă nu există evaluări

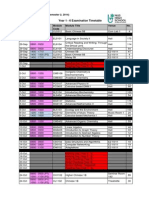

- 2014 Sem 2 Exam Timetable (All Students)Document4 pagini2014 Sem 2 Exam Timetable (All Students)Girish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assembly Programme (Students) 2015 Sem 2Document1 paginăAssembly Programme (Students) 2015 Sem 2Girish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physxprac 1Document3 paginiPhysxprac 1Girish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACE Startups Grant Interest FormDocument4 paginiACE Startups Grant Interest FormGirish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assembly Programme 2015 - Updated PDFDocument5 paginiAssembly Programme 2015 - Updated PDFGirish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Sem 1 Exam Timetable (Students)Document3 pagini2015 Sem 1 Exam Timetable (Students)Girish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of ProfanityDocument10 paginiSex Differences in Uses and Perceptions of ProfanityGirish KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speed Reading SecretsDocument49 paginiSpeed Reading SecretsJets Campbell100% (2)

- Tragic Eikonografy A Conceptual History PDFDocument553 paginiTragic Eikonografy A Conceptual History PDFCristian TeodorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Centre SynopsisDocument12 paginiCultural Centre SynopsisAr Manpreet Prince50% (2)

- Theta Newsletter Spring 2010Document6 paginiTheta Newsletter Spring 2010mar335Încă nu există evaluări

- Student Interest SurveyDocument7 paginiStudent Interest Surveymatt1234aÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narrative Report On The Division SeminarDocument3 paginiNarrative Report On The Division Seminarvincevillamora2k11Încă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Teacher Online Feedback and Leanring MotivationDocument11 pagini2020 Teacher Online Feedback and Leanring MotivationArdah msÎncă nu există evaluări

- 台灣學生關係子句習得之困難Document132 pagini台灣學生關係子句習得之困難英語學系陳依萱Încă nu există evaluări

- SPED 425-001: Educational Achievement Report Towson University Leah Gruber Dr. Fewster 4/30/15Document12 paginiSPED 425-001: Educational Achievement Report Towson University Leah Gruber Dr. Fewster 4/30/15api-297261081Încă nu există evaluări

- Capitol University Medical Center PoliciesDocument5 paginiCapitol University Medical Center PoliciesCharles CagaananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speak OutDocument44 paginiSpeak OutJackie MurtaghÎncă nu există evaluări

- J.B. WatsonDocument14 paginiJ.B. WatsonMuhammad Azizi ZainolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cps in FypDocument4 paginiCps in FypMuhammadHafiziÎncă nu există evaluări

- CompeTank-En EEMUA CourseDocument6 paginiCompeTank-En EEMUA CoursebacabacabacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-assessment form for term-end social work activityDocument10 paginiSelf-assessment form for term-end social work activityDeepak SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AssignmentDocument4 paginiAssignmentlalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociology (Latin: Socius, "Companion"; -Ology, "the Study of", Greek λόγος,Document1 paginăSociology (Latin: Socius, "Companion"; -Ology, "the Study of", Greek λόγος,Chloe Penetrante50% (2)

- Zee Learn Annual Report PDFDocument122 paginiZee Learn Annual Report PDFPega Sus CpsÎncă nu există evaluări

- FEU Intro to Architectural Visual 3 and One Point PerspectiveDocument2 paginiFEU Intro to Architectural Visual 3 and One Point Perspectiveangelle cariagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artificial Intelligence Applications in Civil EngineeringDocument31 paginiArtificial Intelligence Applications in Civil Engineeringpuppyarav2726Încă nu există evaluări

- AIDET Competency Assessment ToolDocument2 paginiAIDET Competency Assessment ToolJenrhae LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tie Preparation (Investigation & News)Document4 paginiTie Preparation (Investigation & News)Joanna GuoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pass4sure 400-101Document16 paginiPass4sure 400-101Emmalee22Încă nu există evaluări

- My First Grammar 3 Student Book FullDocument116 paginiMy First Grammar 3 Student Book FullMinhh Hằngg NguyễnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Earth and Life Science: Quarter 1 - Module 12: Relative and Absolute DatingDocument25 paginiEarth and Life Science: Quarter 1 - Module 12: Relative and Absolute Datinghara azurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 2 MAED 213Document1 paginăQuiz 2 MAED 213Ramoj Reveche PalmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Traineeship Scheme Brochure PDFDocument6 paginiManagement Traineeship Scheme Brochure PDFShueab MujawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team Effectiveness - Fawad LatifDocument13 paginiTeam Effectiveness - Fawad LatifFatima Iqbal100% (1)

- IIE Law Referencing Guide 2020Document20 paginiIIE Law Referencing Guide 2020Carmel PeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection On Madrasah EducationDocument2 paginiReflection On Madrasah EducationAding SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe la EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De la EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (110)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (13)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossDe la EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (78)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe la EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (402)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDe la EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDe la EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (169)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDe la EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe la EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDe la EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementDe la EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (40)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Secure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeDe la EverandSecure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (17)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDe la EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDe la EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (253)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassDe la EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (22)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDe la EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (327)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesDe la EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (34)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe la EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (8)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDe la EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (44)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (3)

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIDe la EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (19)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!De la EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Seeing What Others Don't: The Remarkable Ways We Gain InsightsDe la EverandSeeing What Others Don't: The Remarkable Ways We Gain InsightsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (288)

- Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisDe la EverandDaniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (130)