Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Uses of Piaget in Classroom

Încărcat de

NidhiDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Uses of Piaget in Classroom

Încărcat de

NidhiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

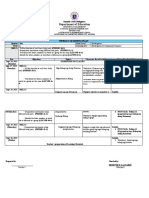

Uses of Piagets Theory in the Classroom

Teaching the Preoperational Child

(Toddler; Early Childhood; 2&1/2-6 years old)

Use concrete props and visual aids

to illustrate lessons and help

children understand what is being

presented.

Make instructions relatively short,

using actions as well as words, to

lessen likelihood that the students

will get confused.

Do not expect the students to find it

easy to see the world from someone

else's perspective since they are

likely to be very egocentric at this

point.

Give children a great deal of

physical practice with the facts and

skills that will serve as building

blocks for later development.

Encourage the manipulation of

physical objects that can change in

shape while retaining a constant

mass, giving the students a chance

to move toward the understanding

of conservation and two-way logic

needed in the next stage.

Provide many opportunities to

experience the world in order to

build a foundation for concept

learning and language.

Use physical illustrations.

Use drawings and

illustrations.

After giving instructions,

ask a student to demonstrate

them as a model for the rest

of the class.

Explain a game by acting

out the part of a participant.

Avoid lessons about worlds

too far removed from the

child's experience.

Discuss sharing from the

child's own experience.

Use cut-out letters to build

words.

Avoid overuse of

workbooks and other paperand-pencil tasks.

Provide opportunities to

play with clay, water, or

sand.

Engage students in

conversations about the

changes the students are

experiencing when

manipulating objects.

Take field trips.

Use and teach words to

describe what they are

seeing, doing, touching,

tasting, etc.

Discuss what they are

seeing on TV.

Teaching the Concrete Operational Child

(Middle Childhood; 6-12 years old)

Continue to use concrete props and

visual aids, especially when dealing

with sophisticated material.

Continue to give students a chance

to manipulate objects and test out

their ideas.

Make sure that lectures and

readings are brief and well

organized.

Ask students to deal with no more

than three or four variables at a

time.

Use familiar examples to help

explain more complex ideas so

students will have a beginning point

for assimilating new information.

Provide time-lines for

history lessons.

Provide three-dimensional

models in science.

Demonstrate simple

scientific experiments in

which the students can

participate.

Show craftwork to illustrate

daily occupations of people

of an earlier period.

Use materials that present a

progression of ideas from

step to step.

Have students read short

stories or books with short,

logical chapters, moving to

longer reading assignments

only when the students are

ready.

Require readings with a

limited number of

characters.

Demonstrate experiments

with a limited number of

steps.

Compare students' own lives

with those of the characters

in a story.

Use story problems in

mathematics.

Give opportunities to classify and

group objects and ideas on

increasingly complex levels.

Present problems which require

logical, analytical thinking to solve.

Give students separate

sentences on slips of paper

to be grouped into

paragraphs.

Use outlines, hierarchies,

and analogies to show the

relationship of unknown

new material to already

acquired knowledge.

Provide materials such as

Mind Twisters, Brain

Teasers, and riddles.

Focus discussions on openended questions which

stimulate thinking (e.g., are

the mind and the brain the

same thing?)

Teaching Students Beginning to Use Formal Operations

(Adolescence; 12-19 years old)

Continue to use many of the

teaching strategies and materials

appropriate for students at the

concrete operational stage.

Give students an opportunity to

explore many hypothetical

questions.

Encourage students to explain how

they solve problems.

Use visual aids such as

charts and illustrations, as

well a simple but somewhat

more sophisticated graphs

and diagrams.

Use well-organized

materials that offer step by

step explanations.

Provide students

opportunities to discuss

social issues.

Provide consideration of

hypothetical "other worlds."

Ask students to work in

pairs with one student acting

as the problem solver,

thinking aloud while

tackling a problem, with the

other student acting as the

listener, checking to see that

all steps are mentioned and

that everything seems

logical.

Whenever possible, teach broad

concepts, not just facts, using

materials and ideas relevant to the

students.

Make sure that at least some

of the tests you give ask for

more than rote memory or

one final answer; essay

questions, for example,

might ask students to justify

two different positions on an

issue.

While discussing a topic

such as the Civil War,

consider what other issues

have divided the country

since then.

Use lyrics from popular

music to teach poetic

devices, to reflect on social

problems, and so on.

From website:

http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/cogsys/piagtuse.html

Materials have been adapted from: Woolfolk & McCune-Nicolich. (1984). Educational

psychology for teachers. (2nd Ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Business Communication Today: Communication Challenges in A Diverse, Global MarketplaceDocument35 paginiBusiness Communication Today: Communication Challenges in A Diverse, Global MarketplaceElissa JorgensenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced English Vocabulary 123Document3 paginiAdvanced English Vocabulary 123RaheelAfzaalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociology of EducationDocument4 paginiSociology of EducationJohn Nicer AbletisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics Lesson Plan For Grade 2Document6 paginiMathematics Lesson Plan For Grade 2Caryn Vicente Ragudo100% (6)

- Orientation: Pre-Immersion - Grade 12Document3 paginiOrientation: Pre-Immersion - Grade 12Alex Abonales Dumandan100% (3)

- Complete Danish - Teach YourselfDocument2 paginiComplete Danish - Teach YourselfSusanna Muratori0% (2)

- AAS Application Form Muhammad AdamDocument32 paginiAAS Application Form Muhammad AdamDl Dl0% (1)

- Lesson Plans For I-Learn Smart Start 1Document81 paginiLesson Plans For I-Learn Smart Start 1Khanh Nguyễn Văn100% (3)

- Conventional Center ThesisDocument153 paginiConventional Center Thesisshreenu21120480% (10)

- Chapter 1 Doing PhilosophyDocument13 paginiChapter 1 Doing PhilosophyAdrian DimaunahanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ctet Main Question Paper I January 2021 1792Document56 paginiCtet Main Question Paper I January 2021 1792Anita DrallÎncă nu există evaluări

- CVMD Verl Instructions To Candidates-Eng-V2Document3 paginiCVMD Verl Instructions To Candidates-Eng-V2api-658341788Încă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines STPDocument7 paginiGuidelines STPSomil RahejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- State QuotaDocument3 paginiState QuotaSHREEWOODÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ph.D. Rules and Regulations 2011-12Document13 paginiPh.D. Rules and Regulations 2011-12Venkat Dayanand TirunagariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Y5L Open EveningDocument27 paginiY5L Open Eveningjamiestark427Încă nu există evaluări

- Topic 1Document2 paginiTopic 1Jhe Neh VahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume Rebecca RouthierDocument3 paginiResume Rebecca Routhierapi-305647618Încă nu există evaluări

- Inquiry Project Proposal by Kathena SiegelDocument4 paginiInquiry Project Proposal by Kathena SiegelKathena SiegelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilts Lis Content-Area TestDocument2 paginiIlts Lis Content-Area Testapi-413943348Încă nu există evaluări

- Designing Integrated Research Integrity Training: Authorship, Publication, and Peer ReviewDocument12 paginiDesigning Integrated Research Integrity Training: Authorship, Publication, and Peer ReviewviviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prospectus 2016 17Document126 paginiProspectus 2016 17Adv Sunil KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- EMIS - Tamil Nadu SchoolsDocument9 paginiEMIS - Tamil Nadu SchoolsVijayarajÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Does New Zealand's Education System Compare?Document37 paginiHow Does New Zealand's Education System Compare?KhemHuangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week6 WLPDocument2 paginiWeek6 WLPJessica EustaquioÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCIENCE 5e's Lesson Plan About DistanceDocument7 paginiSCIENCE 5e's Lesson Plan About DistanceZALVIE FERNANDO UNTUAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Positive and Negative Mood On University Students' Learning and Academic Performance: Evidence From IndonesiaDocument12 paginiThe Effects of Positive and Negative Mood On University Students' Learning and Academic Performance: Evidence From IndonesiaTesa KaunangÎncă nu există evaluări

- West-Moynes MaryLynn H 201206 PHD ThesisDocument368 paginiWest-Moynes MaryLynn H 201206 PHD Thesisdiana_vataman_1100% (1)

- RRL & RRS in Importance of OJTDocument3 paginiRRL & RRS in Importance of OJTMaTheresa HabanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ched Memorandum Order No. - Series of 2020: Commission On Higher EducationDocument8 paginiChed Memorandum Order No. - Series of 2020: Commission On Higher EducationRainiel Victor M. CrisologoÎncă nu există evaluări