Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Civil Law Cases On Property

Încărcat de

yemyemcTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Civil Law Cases On Property

Încărcat de

yemyemcDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

MOVABLE AND IMMOVABLE PROPERTY

1. Ladera vs Hodges

2. Mindanao Bus Co., vs City Assessor and treasurer

Doctrine:

PROPERTY;

IMMOVABLE

PROPERTY

BY

DESTINATION;

TWO

REQUISITES

BEFORE

MOVABLES MAY BE DEEMED TO HAVE BEEN

IMMOBILIZED; TOOLS AND EQUIPMENTS MERELY

INCIDENTAL TO BUSINESS NOT SUBJECT TO REAL

ESTATE TAX. Movable equipments, to be

immobilized in contemplation of Article 415 of the Civil

Code, must be the essential and principal elements of

an industry or works which are carried on in a building

or on a piece of land. Thus, where the business is one

of transportation, which is carried on without a repair or

service shop, and its rolling equipment is repaired or

serviced in a shop belonging to another, the tools and

equipments in its repair shop which appear movable

are merely incidentals and may not be considered

immovables, and, hence, not subject to assessment as

real estate for purposes of the real estate tax.

3. Makati Leasing & Finance vs Weaver Textiles

Doctrine:

CIVIL LAW; PROPERTY; MACHINERY THOUGH

IMMOBILIZED BY DESTINATION IF TREATED BY

THE PARTIES AS A PERSONALTY FOR PURPOSES

OF A CHATTEL MORTGAGE LEGAL, WHERE NO

THIRD PARTY IS PREJUDICED. The next and the

more crucial question to be resolved in this petition is

whether the machinery in suit is real or personal

property from the point of view of the parties.

Examining the records of the instance case, the

Supreme Court found no logical justification to exclude

and rule out, as the appellate court did, the present

case from the application of the pronouncement in the

TUMALAD v. VICENCIO CASE (41 SCRA 143) where

a similar, if not identical issue was raised. If a house of

strong materials, like what was involved in the Tumalad

case may be considered as personal property for

purposes of executing a chattel mortgage thereon as

long as the parties to the contract so agree and no

innocent third party will be prejudiced thereby, there is

absolutely no reason why a machinery, which is

movable in its nature and becomes immobilized only by

destination or purpose, may not be likewise treated as

such. This is really because one who has so agreed is

estopped from denying the existence of the chattel

mortgage.

4. Santos Evangelista vs Alto Surety & Insurance Corp.

Doctrine:

PROPERTY; HOUSE IS NOT PERSONAL BUT REAL

PROPERTY FOR PURPOSES OF ATTACHMENT. A

house is not personal property, much less a debt, credit

or other personal property capable of manual delivery,

but immovable property "A true building (not merely

superimposed on the soil), is immovable or real

property, whether it is erected by the owner of the land

or by a usufructuary or lessee" (Laddera vs. Hodges,

48 Off. Gaz., 5374.) and the attachment of such

building is subject to the provisions of subsection (a) of

section 7, Rule 59 of the Rules of Court.

5. Tsai Vs CA

Doctrine:

6. Sergs Products vs PCI

Doctrine:

CIVIL LAW; CONTRACTS; CONTRACTING PARTIES

MAY VALIDLY STIPULATE THAT REAL PROPERTY

BE CONSIDERED AS PERSONAL. The Court has

held that contracting parties may validly stipulate that a

real property be considered as personal. After agreeing

to such stipulation, they are consequently estopped

from claiming otherwise. Under the principle of

estoppel, a party to a contract is ordinarily precluded

from denying the truth of any material fact found

therein. Hence, in Tumalad v. Vicencio, the Court

upheld the intention of the parties to treat a house as a

personal property because it had been made the

subject of a chattel mortgage. The Court ruled: ". . . .

Although there is no specific statement referring to the

subject house as personal property, yet by ceding,

selling or transferring a property by way of chattel

mortgage defendants-appellants could only have

meant to convey the house as chattel, or at least,

intended to treat the same as such, so that they should

not now be allowed to make an inconsistent stand by

claiming otherwise." Applying Tumalad, the Court in

Makati Leasing and Finance Corp. v. Wearever Textile

Mills also held that the machinery used in a factory and

essential to the industry, as in the present case, was a

proper subject of a writ of replevin because it was

treated as personal property in a contract. Cc||| (Serg's

Products, Inc. v. PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc., G.R.

No. 137705, August 22, 2000)

7. Burgos vs Chief of Staff

Doctrine:

CIVIL LAW; PROPERTY; MACHINERIES INTENDED

FOR AN INDUSTRY WHICH MAY BE CARRIED ON IN

A BUILDING WHEN PLACED BY A TENANT REMAIN

MOVABLE PROPERTY SUSCEPTIBLE TO SEIZURE;

CASE AT BAR. Under Article 415 [5] of the Civil

Code of the Philippines, "machinery, receptacles.

instruments or implements intended by the owner of

the tenement for an industry or works which may be

carried on in a building or on a piece of land and which

tend directly to meet the needs of the said industry or

works" are considered immovable property . In Davao

Sawmill Co. vs. Castillo (61 Phil. 709) where this legal

provision was invoked, this Court ruled that machinery

which is movable by nature becomes immobilized

when placed by the owner of the tenement, property or

plant, but not so when placed by a tenant, usufructuary,

or any other person having only a temporary right,

unless such person acted as the agent of the owner. In

the case at bar, petitioners do not claim to be the

owners of the land and/or building on which the

machineries were placed. This being the case, the

machineries in question, while in fact bolted to the

ground remain movable property susceptible to seizure

under a search warrant.||| (Burgos, Sr. v. Chief of Staff,

G.R. No. 64261, December 26, 1984)

8. Lopez vs Orosa

Doctrine:

PROPERTY; REAL ESTATE; MATERIALMAN'S

LIEN; DOES NOT EXTEND TO THE LAND;

BUILDING SEPARATE AND DISTINCT FROM

LAND. Appellant's contention that the lien

executed in favor of the furnisher of the materials

used for the construction, repair or refection of a

building is also extended to land on which the

construction was made is without merit, because

while it is true that generally, real estate connotes

the land and the building constructed thereon, it is

obvious that the inclusion of the building, separate

and distinct from the land, in the enumeration of

what constitute real properties (Art. 415 of the New

Civil Code [Art. 334 of the old]) could mean only one

thing, that a building is by itself an immovable

property. (Leung Yee vs. Strong Machinery Co., 37

Phil. 644.)

2.ID.; ID.; ID.; BUILDING AS IMMOVABLE

PROPERTY; IRRESPECTIVE OF OWNERSHIP OF

LAND AND BUILDING. A building is an

immovable property irrespective of whether or not

said structure and the land on which it is adhered to

belong to the same owner.

9. Yap vs Tanada

Doctrine:

CIVIL LAW; PROPERTY; IMMOVABLE PROPERTY;

WATER PUMP INSTALLED IN RESIDENCE BUT

REMOVABLE WITHOUT DETERIORATION, NOT

IMMOVABLE PROPERTY The Civil Code considers

as immovable property, among others, anything

"attached to an immovable in a fixed manner, in such a

way that it cannot be separated therefrom without

breaking the material or deterioration of the object."

The pump does not fit this description. It could be, and

was in fact separated from Yap's premises without

being broken or suffering deterioration. Obviously the

separation or removal of the pump involved nothing

more complicated than the loosening of bolts or

dismantling of other fasteners.

10. Machinery & Engineering Supplies Inc., vs CA

Doctrine:

APPLICABLE

ONLY

TO

RECOVER

PERSONAL PROPERTY. Ordinarily replevin may

be brought to recover any specific personal property

unlawfully taken or detained from the owner thereof,

provided such property is capable of identification

and delivery; but replevin will not lie for the recovery

of real property or incorporeal personal property.

4.ID.; MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT, WHEN

IMMOVABLE. The machinery and equipment in

question appeared to be attached to the land,

particularly to the concrete foundation of a building,

in a fixed manner, in such a way that the former

could not be separated from the latter without

breaking the material or deterioration of the object.

Hence, in order to remove said outfit, it became

necessary not only to unbolt the same, but to also

cut some of its wooden supports. Said machinery

and equipment were "intended by the owner of the

tenement for an industry" carried on said immovable

and tended "directly to meet the needs of said

industry." For these reasons, they were already

immovable pursuant to paragraph 3 and 5 of Article

415 of Civil Code of the Philippines.

5.ID.; RESTITUTION; REINSTALLATION OF

DISMANTLED AND REMOVED PROPERTY IN ITS

ORIGINAL CONDITION. When the restitution of

what has been taken by way of replevin has been

ordered, the goods in question shall be returned in

substantially the same condition as when taken (54

C. J., 599-600, 640-641). Inasmuch as the

machinery and equipment involved in this case were

duly installed and affixed in the premises of

respondent

company

when

petitioner's

representative caused said property to be

dismantled and then removed, it follows that

petitioner must also do everything necessary to the

reinstallation of said property in conformity with its

original condition.

PUBLIC DOMINION AND PRIVATE OWENRSHIP

1. LAUREL VS GARCIA

Doctrine:

2. Rabuco vs Villegas

Doctrine

3. Macasiano vs Diokno

Doctrine:

PROPERTY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT DEVOTED

TO PUBLIC SERVICE; DEEMED PUBLIC; UNDER

THE ABSOLUTE CONTROL OF CONGRESS; LOCAL

GOVERNMENTS HAVE NO AUTHORITY TO

CONTROL OR REGULATE THEM UNLESS SPECIFIC

AUTHORITY IS VESTED UPON THEM BY

CONGRESS; AUTHORITY TO BE INTERPRETED

ACCORDING TO BASIC PRINCIPLES OF LAW; ART.

424 OF THE CIVIL CODE. Properties of the local

government which are devoted to public service are

deemed public and are under the absolute control of

Congress (Province of Zamboanga del Norte v. City of

Zamboanga, L-24440, March 28, 1968, 22 SCRA

1334). Hence, local governments have no authority

whatsoever to control or regulate the use of public

properties unless specific authority is vested upon them

by Congress. One such example of this authority given

by Congress to the local governments is the power to

close roads as provided in Section 10, Chapter II of the

Local Government Code, which states: "SEC. 10.

Closure of roads. A local government unit may

likewise, through its head acting pursuant to a

resolution of its sangguniang and in accordance with

existing law and the provisions of this Code, close any

barangay, municipal, city or provincial road, street,

alley, park or square. No such way or place or any part

thereof shall be closed without indemnifying any

person prejudiced thereby. A property thus withdrawn

from public use may be used or conveyed for any

purpose for which other real property belonging to the

local unit concerned might be lawfully used or

conveyed." However, the aforestated legal provision

which gives authority to local government units to close

roads and other similar public places should be read

and interpreted in accordance with basic principles

already established by law. These basic principles have

the effect of limiting such authority of the province, city

or municipality to close a public street or thoroughfare.

Article 424 of the Civil Code lays down the basic

principle that properties of public dominion devoted to

public use and made available to the public in general

are outside the commerce of man and cannot be

disposed of or leased by the local government unit to

private persons.

4.ROADS AND STREETS ORDINARILY USED FOR

VEHICULAR TRAFFIC CONSIDERED PUBLIC

PROPERTY; LOCAL GOVERNMENT HAS NO

POWER TO USE IT FOR ANOTHER PURPOSE OR

TO DISPOSE OF OR LEASE IT TO PRIVATE

PERSONS. However, those roads and streets which

are available to the public in general and ordinarily

used for vehicular traffic are still considered public

property devoted to public use. In such case, the local

government has no power to use it for another purpose

or to dispose of or lease it to private persons.

5.PROPERTY WITHDRAWN FROM PUBLIC USE;

BECOMES PATRIMONIAL PROPERTY OF THE

LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNIT; CAN BE OBJECT OF

ORDINARY CONTRACT. When it is already

withdrawn from public use, the property then becomes

patrimonial property of the local government unit

concerned (Article 422, Civil Code; Cebu Oxygen, etc.

et al. v. Bercilles, et al., G.R. No. L-40474, August 29,

1975, 66 SCRA 481). It is only then that the respondent

municipality can "use or convey them for any purpose

for which other real property belonging to the local unit

concerned might be lawfully used or conveyed" in

accordance with the last sentence of Section 10,

Chapter II of Blg. 333, known as Local Government

Code. Such withdrawn portion becomes patrimonial

property which can be the object of an ordinary

contract (Cebu Oxygen and Acetylene Co., Inc. v.

Bercilles, et al., G.R. No. L-40474, August 29, 1975, 66

SCRA 481).

4. Republic vs Ca

Doctrine:

CIVIL

LAW;

LAND

TITLES

AND

DEEDS;

COMMONWEALTH ACT NO. 141 (PUBLIC LAND

ACT); LAND ACQUIRED UNDER A FREE PATENT;

PRESCRIPTION AGAINST ENCUMBRANCE. The

provisions under Secs. 118, 121, 122 and 124 of the

Commonwealth Act No. 141 (Public Land Act) clearly

proscribe the encumbrance of a parcel of land acquired

under a free patent or homestead within five years from

the grant of such patent. Furthermore, such

encumbrance results in the cancellation of the grant

and the reversion of the land to the public domain. The

prohibition against any alienation or encumbrance of

the land grant is a proviso attached to the approval of

every application. Prior to the fulfillment of the

requirements of law, Respondent Morato had only an

inchoate right to the property; such property remained

part of the public domain and, therefore, not

susceptible to alienation or encumbrance. Conversely,

when a "homesteader has complied with all the terms

and conditions which entitled him to a patent for [a]

particular tract of public land, he acquires a vested

interest therein and has to be regarded an equitable

owner. thereof." However, for Respondent Morato's title

of ownership over the patented land to be perfected,

she should have complied with the requirements of the

law, one of which was to keep the property for herself

and her family within the prescribed period of five (5)

years. Prior to the fulfillment of all requirements of the

law, Respondent Morato's title over the property was

incomplete. Accordingly. if the requirements are not

complied with, the State as the grantor could petition

for the annulment of the patent and the cancellation of

the title.

5. Province of Zamboanga Del Norte vs City of

Zamboanga

Doctrine:

POLITICAL LAW; MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS;

PROVINCES;

PATRIMONIAL

AND

PUBLIC

PROPERTIES THEREOF, DISPUTE AS TO PROPER

CLASSIFICATION OF PROPERTY INVOLVED IN

INSTANT CASE; CASE REMANDED TO LOWER

COURT FOR DETERMINATION THEREOF. Where

in its motion for reconsideration of the main decision of

this Court declaring that Republic Act 3039 is

unconstitutional and void in so far as the same seeks to

deprive the Province of Zamboanga del Norte of its

share in the 26 lots situated within the City of

Zamboanga, without just compensation, for the reason

that said 26 lots are patrimonial property of the old

Province of Zamboanga, the movant City of

Zamboanga contends that the said lots are not

patrimonial property of the former Province of

Zamboanga, said 26 lots having been always used for

public purposes, such as school sites, playgrounds and

athletic fields for schools, while the appellee Province

of Zamboanga contends that the evidence sought to be

filed by movant relative to its contention is not newly

discovered evidence and is therefore inadmissible at

this stage of the proceedings and in the alternative, that

it has additional evidence to show that most of these

lots are not actually devoted to public use, in the

interest of justice and equity, the main decision of this

Court should be reconsidered and set aside, in so far

as the 26 lots and the monetary indemnities involved

are concerned. Instead, the records of the case should

be remanded to the court of origin for new trial, in order

to determine whether or not the 26 lots were or were

not actually devoted to public use or governmental

purposes prior to the enactment of Republic Act 3039.

6. Chaves v Public Estates

Doctrine:

PATRIMONIAL PROPERTY CAN BE SOLD TO

PRIVATE PARTIES. Government owned lands, as

long they are patrimonial property, can be sold to

private parties, whether Filipino citizens or qualified

private corporations. Thus, the so-called Friar Lands

acquired by the government under Act No. 1120 are

patrimonial property which even private corporations

can acquire by purchase. Likewise, reclaimed alienable

lands of the public domain if sold or transferred to a

public or municipal corporation for a monetary

consideration become patrimonial property in the

hands of the public or municipal corporation. Once

converted to patrimonial property, the land may be sold

by the public or municipal corporation to private parties,

whether Filipino citizens or qualified private

corporations.

7. Villarico vs Sarmiento

Doctrine:

It is not disputed that the lot on which petitioner's

alleged "right of way" exists belongs to the state or

property of public dominion. Property of public

dominion is defined by Article 420 of the Civil Code as

follows:

"ART. 420.The following things are

property of public dominion:

(1)Those intended for public use such

as roads, canals, rivers, torrents, ports

and bridges constructed by the State,

banks, shores, roadsteads, and other of

similar character.

(2)Those which belong to the State,

without being for public use, and are

intended for some public service or for

the development of the national wealth."

Public use is "use that is not confined to privileged

individuals, but is open to the indefinite public." 6

Records show that the lot on which the stairways were

built is for the use of the people as passageway to the

highway. Consequently, it is a property of public

dominion.

Property of public dominion is outside the commerce of

man and hence it: (1) cannot be alienated or leased or

otherwise be the subject matter of contracts; (2) cannot

be acquired by prescription against the State; (3) is not

subject to attachment and execution; and (4) cannot be

burdened by any voluntary easement. 7

Considering that the lot on which the stairways were

constructed is a property of public dominion, it can not

be burdened by a voluntary easement of right of way in

favor of herein petitioner. In fact, its use by the public is

by mere tolerance of the government through the

DPWH. Petitioner cannot appropriate it for himself.

Verily, he cannot claim any right of possession over it.

OWNERSHIP

1. Javier vs Veridiano

Doctrine:

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Exempting CircumstancesDocument4 paginiExempting CircumstancesyemyemcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Specpro Case DigestDocument3 paginiSpecpro Case DigestyemyemcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hernandez Vs AndalDocument4 paginiHernandez Vs AndalyemyemcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Castro, Remy B. Salonga-Hernandez Vs Pascual: Pascual-Bautista, Applying Article 992 of The Civil CodeDocument4 paginiCastro, Remy B. Salonga-Hernandez Vs Pascual: Pascual-Bautista, Applying Article 992 of The Civil CodeyemyemcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Dee Chua & Sons v. CIR, G.R. No. L-2216, 31 Jan 1950Document4 paginiDee Chua & Sons v. CIR, G.R. No. L-2216, 31 Jan 1950Ron AceroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug Law Enforcement: Narcotics Control BureauDocument160 paginiDrug Law Enforcement: Narcotics Control BureausameerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deed of Absolute SaleDocument1 paginăDeed of Absolute SaleAquilino Alibosa Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- LEC 2017 - Post-Test in Comparative Police SystemDocument7 paginiLEC 2017 - Post-Test in Comparative Police SystemBokhary Dimasangkay Manok EliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cold War ReviewDocument25 paginiThe Cold War Reviewegermind90% (21)

- Theodore G. Bilbo - Take Your Choice - Separation or Mongrelization (1946)Document227 paginiTheodore G. Bilbo - Take Your Choice - Separation or Mongrelization (1946)gibmedat100% (1)

- ELTA-ELI-2139-GreenLotus-Multi-sensor System For Situational Awareness - 0Document2 paginiELTA-ELI-2139-GreenLotus-Multi-sensor System For Situational Awareness - 0Zsolt KásaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample of Program of Instruction: Framework For The List of Competencies Required of Maneuver Units)Document23 paginiSample of Program of Instruction: Framework For The List of Competencies Required of Maneuver Units)Provincial DirectorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Usurpation of Real RightsDocument7 paginiUsurpation of Real RightsTukneÎncă nu există evaluări

- HRC Corporate Equality Index 2018Document135 paginiHRC Corporate Equality Index 2018CrainsChicagoBusinessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monastic Inter Religious Dialogue - An Interview With Swami ADocument5 paginiMonastic Inter Religious Dialogue - An Interview With Swami APaplu PaulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ket Grammar ExercisesDocument2 paginiKet Grammar ExercisesCMRotaru100% (2)

- Space Opera Adv - 1Document24 paginiSpace Opera Adv - 1Jacopo Jbb ColabattistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labour Law ProjectDocument26 paginiLabour Law Projecthargun100% (1)

- Duque Vs VelosoDocument11 paginiDuque Vs VelosoStephen Jasper Samson100% (1)

- Instruments Surgery PDFDocument103 paginiInstruments Surgery PDFTonyScaria100% (1)

- Development & Formal Reception of English LawDocument28 paginiDevelopment & Formal Reception of English Lawookay100% (1)

- PenguinDocument4 paginiPenguinAngela FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Grizzlies Walked UprightDocument3 paginiWhen Grizzlies Walked Uprightleah_m_ferrillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Airfreight 2100, Inc.Document2 paginiAirfreight 2100, Inc.ben carlo ramos srÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Anthony Frank Gaggi, Henry Borelli, Peter Lafroscia, Ronald Ustica, Edward Rendini and Ronald Turekian, 811 F.2d 47, 2d Cir. (1987)Document23 paginiUnited States v. Anthony Frank Gaggi, Henry Borelli, Peter Lafroscia, Ronald Ustica, Edward Rendini and Ronald Turekian, 811 F.2d 47, 2d Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roy Padilla, Et Al V. Court of AppealsDocument1 paginăRoy Padilla, Et Al V. Court of AppealsJill BagaoisanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Racca and Racca vs. Echague (January 2021) - Civil Law Succession Probate of Will PublicationDocument20 paginiRacca and Racca vs. Echague (January 2021) - Civil Law Succession Probate of Will Publicationjansen nacarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four of The Most Basic Leadership Styles AreDocument8 paginiFour of The Most Basic Leadership Styles AreMc SuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- People of The Philippines, Plaintiff, vs. Judy Anne SantosDocument30 paginiPeople of The Philippines, Plaintiff, vs. Judy Anne SantosKirby HipolitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Travel Insurance: Insurance Product Information DocumentDocument4 paginiTravel Insurance: Insurance Product Information DocumentPetluri TarunÎncă nu există evaluări

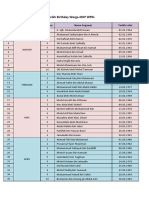

- Tarikh Besday 2023Document4 paginiTarikh Besday 2023Wan Firdaus Wan IdrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- D BibliographyDocument3 paginiD BibliographyArun AntonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- UK Home Office: LincolnshireDocument36 paginiUK Home Office: LincolnshireUK_HomeOfficeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Do States Mostly Obey International LawDocument12 paginiWhy Do States Mostly Obey International Lawshabnam BarshaÎncă nu există evaluări