Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A Linguistic Toolbox For Discourse Analysis

Încărcat de

LaViruTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Linguistic Toolbox For Discourse Analysis

Încărcat de

LaViruDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Discourse Studies

http://dis.sagepub.com/

A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis: towards a multidimensional handling of verbal interactions

Laurent Rouveyrol, Claire Maury-Rouan, Robert Vion and Marie-Christine Nol-Jorand

Discourse Studies 2005 7: 289

DOI: 10.1177/1461445605052188

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://dis.sagepub.com/content/7/3/289

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Discourse Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://dis.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://dis.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://dis.sagepub.com/content/7/3/289.refs.html

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

A RT I C L E

289

A linguistic toolbox for discourse

analysis: towards a multidimensional

handling of verbal interactions

L AU R E N T RO U V E Y RO L ,

C L A I R E M A U RY- R O UA N , R O B E R T V I O N A N D

MARIE-CHRISTINE NOL-JORAND

U N I V E R S I T D E P RO V E N C E A N D FA C U L T D E M D E C I N E ,

LA TIMONE, MARSEILLE

Discourse Studies

Copyright 2005

SAGE Publications.

(London, Thousand Oaks,

CA and New Delhi)

www.sagepublications.com

Vol 7(3): 289313.

1461-4456

(200508) 7:3;

10.1177/1461445605052188

This article is aimed at introducing a French discourse analysis

model, e.g. the star model, initiated by the LAA team led by Robert Vion in

Aix-en-Provence, to English-speaking researchers. It will be argued that

language activity is multi-dimensional and can be traced at various

heterogeneous levels of speech productions belonging to macro as well as

micro orders. Speakers achieve different varieties of positioning which result in

negotiating an interactional space within a pre-given situation. The model is

precisely designed to offer a unified and comprehensive view of such

heterogeneous phenomena in constant interconnection. In this study, we also

intend to illustrate our approach through the analysis of two different corpora.

Speakers strategies under extreme conditions will be analysed; the various

sequences used were taken from a special corpus which we were asked to study

as part of a national research programme. In order to illustrate interactional

space shifts, we will also use the transcript of a meeting which took place

between a patient and a medical investigator in a hospital in Marseilles.

A B S T R AC T

KEY WORDS:

discourse analysis, enunciation, integrative pragmatics, positioning

strategies, verbal interaction

1. Introduction

Any situation of communication is characterized by multidimensional parameters. Every speech production, whatever it may be, is necessarily related to a

discourse genre or interaction type. In this pre-existing setting, every subject will

initiate, undergo and negotiate an interactive space with his/her partners in

which he/she simultaneously handles various positions, or to be more exact,

various positioning processes. What is needed in order to describe verbal interactions is an overall theory capable of taking into account the general dynamics of

speech production and reception in its full complexity and heterogeneity. An

example of this integrative pragmatics approach has been developed by Vion

(1995, 1999) and constitutes the theoretical basis of the LAA team.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

290 Discourse Studies 7(3)

The model initiated by the LAA team originates from Vion (1995) mainly, and

was originally designed to deal with natural conversation; later, the initial model

was adapted to take into account other forms of communication as well, providing analyses oriented towards various goals. While Bertrand et al. on emotional

talk (2000), Priego-Valverde on humour (1998, 2001), Maury-Rouan on coenunciation (1998) and on discourse particles (2001b), Brmond on discourse

structure and particles (2003) all used natural conversations as corpora, the

model has also been successfully applied to literary discourse (Vion et al., 2002),

media discourse in English (Rouveyrol, 1998), and doctorpatient interactions

(Priego-Valverde and Maury-Rouan, 2003). Concepts were developed or introduced on the grounds of these various kinds of corpora: taxemes (Rouveyrol,

1999), hypocorrection (Maury-Rouan, 2001a), discourse structuration in

general: on effacement strategies (Vion, 2001b), discourse instability (Vion,

2000), positioning changes (Vion, 2001b), taxemic markers (Rouveyrol, 1999),

discourse lures (Maury-Rouan, 2001b, 2003), and modality (Vion, 2001a,

2003). This article is intended to apply the model to a specific corpus consisting

of the verbal productions of members of a scientific team experiencing adaptation to an extreme environment.

The aim of the research group is to carry out discourse analyses bridging the

gap between written and oral communication, monologue and dialogue, thanks

to a model able to deal with the various relevant levels. In our view, speakers

communicate according to social positions and adopt roles. The relation thus

contracted by the different actors and dynamically co-elaborated through discourse activity can be defined in terms of interrelational positioning processes. Such

realities are dissociated into different types which altogether enable the analyst to

map discourse activity bridging the gap between various heterogeneous and

dynamic phenomena. Realities of different calibre have to be handled simultaneously by every speaker. They range from macro to micro, associating social positions to interlocutive, intersubjective and enunciative ones (Vion, 1995: 181).

These positioning processes are complementary and work on a one-to-one

basis: it is not possible to speak from a given position without conjuring up the

addressee in the complementary one and validate the process. If you speak as a

teacher, the addressee can assume no other position than that of a student or

pupil. Such positions, linked to power relations but not always, are initiated in

the course of interaction and are constantly modified.

To situate our research in relation to all other available analytical frames does

not seem to be a realistic task. However, it remains possible to try to target a

certain number of works closely linked to the levels taken into account by our

multidimensional model close to the perspective of enunciative and integrative

pragmatics such as that of Berthoud (1996), Jeanneret (1999) and Verschueren

(1999).

For that reason, instead of beginning this article with a traditional overview

of general questions, we have opted for a presentation of our theoretical perspective step by step, which will enable us to confront our model at each level with

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 291

our different sources, neighbouring approaches among the various current foreground domains in European and international linguistics.

2. Analysing discourse and dialogue: introducing the star model

the state of the art

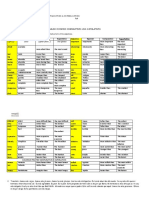

We attempt to analyse discourse by using what we call the star model (Figure 1). If

we start from the top, moving counter-clockwise, we realize that we shift from

macro to micro realities. The first three positioning processes relate to the interpersonal handling of the interaction. Subjects evolve in a social frame, whose

rules and practices they have integrated as members of a specific community.

All five positioning processes: institutional, modular, subjective, discursive,

and enunciative influence each other in a non-hierarchical way and together

form the interactive space. Figure 1 indicates that they are all linked. Careful

independent study in each area of investigation is necessary at the start but the

pursued aim of analysis is to establish such links in their overall dynamics.

Our multidimensional perspective formalizes the complexity of language

from its start. This approach is in sharp contrast to modular attempts in which

language complexity is divided into various components treated relatively

autonomously from each other in a first phase, and connected only in a second

phase.

InstitutionalPositioning

Modular Positioning

Enunciative Positioning

Discursive Positioning

Subjective Positioning

INTERPERSONAL AND SOCIAL

RELATIONS

FIGURE

INTERLOCUTIVE RELATIONS

1. The star model of positioning processes

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

292 Discourse Studies 7(3)

2 . 1 I N S T I T U T I O NA L

P O S I T I O N I N G P RO C E S S E S

Institutional positioning processes are achieved thanks to realities which are

exterior and prior to the interaction. Some examples could be: doctorpatient,

teacherstudent ... These institutional positions refer to a typology of interactions but by no means can be reduced to social functions or professional activities. Communication situations are retro-actively determined by discourse

activity carried out by speakers. Some variation is to be expected, which in the

end modifies or qualifies the pre-existing frame.

We owe much, here, to the interactional sociolinguistics approach whose

inspiration comes from sociology, social anthropology and ultimately linguistics.

Gumperzs work casts light on how subjects share grammatical knowledge and

contextualize it. Institutional positioning processes of sociological order also

echo Erving Goffmans views. Goffman describes how language is used in particular social situations: The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), Behavior in

Public Places (1963), Interactional Rituals (1967), Relations in Public (1971),

Frame Analysis (1974), and Forms of Talk (1981). In the linguistic field, the views

of both authors have been taken up and developed by researchers such as Brown

and Levinson (1987), Schiffrin (1987), Tannen (1989) and more recently Drew

and Heritage (1992). This level of the model is also connected to linguistic genre

theories and verbal interaction typologies Vion (1992, 2000), Bronckart (1996),

Adam (1992, 1997, 1999), Swales (1990).

The institutional positioning process is the broadest type, which in the case

of interactional exchanges enables us to handle the situation and the social

relations at work at the beginning. In written monologal productions, these

institutional processes help us define discourse genres.

2.2 MODULAR

P O S I T I O N I N G P RO C E S S E S

Modular positioning processes have to do with specific interactional phases

handled temporarily by speakers, belonging to a secondary genre subordinated

to the general frame. These phases are called modules in our perspective. To give

an example, in a TV talk show, we could clearly imagine a politician trying to initiate a polemical module with fierce attacks directed at an ideological opponent

within a friendly debate. Another example would be a doctorpatient interaction

in which speakers might initiate conversational modules on children/the

weather. The doctor could even ask the patient for advice on matters such as software, mechanics. The dominant genre is still the medical consultation; conversational modules are local subordinate genres. At this level, we are not far from the

concepts of discourse types and orders of discourse, developed by Fairclough

(1989, 1995), derived from Foucault (1984).

Modular and institutional processes are also conceptually connected to the

perspectives of ESP (English for Specific Purposes) analysis. Anglo-Saxon

research in applied linguistics has produced abundant data in this perspective, in

which a relation between interaction and professional settings is drawn, Business

English is an example. Scientific discourse was analysed by Swales (1990) among

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 293

others. Media discourse has also been thoroughly discussed by Bell and Garrett

(1998). The critical discourse analysis approach produced the greater part of

media discourse analysis; Fairclough (1989, 1995, 2000) uses Hallidays microlinguistic systems (1973; Halliday and Hasan, 1976) as a basis. French-speaking

researchers such as Ghiglione (1989) have focused on political discourse without

necessarily considering a general set of media discourse social practices. Few

Anglo-Saxon researchers have worked on debates; Livingstone and Lunt (1994)

are among the exceptions. Most researchers focus mainly on the case of news,

scrutinizing discourse practices (Van Dijk, 1998), or issues of neutrality

(Clayman, 1992).

2.3 SUBJECTIVE

P O S I T I O N I N G P RO C E S S E S

Subjective positioning processes are to do with the relation established between

the verbal exchange dynamic and the general objectives which speakers assign

themselves. We here consider images of self in relation to hierarchical positioning processes built in the course of the interaction; such processes are linked to

the more general notion of Ethos derived from ancient rhetorics (Amossy, 1999).

Such built images are also connected to discourse situations, for example in the

media and institutional settings, as shown by Ghiglione and Charaudeau (1999),

Scannell (1991), Vion (1998c) and Adam in Amossy (1999). Our concept of

images of self is based on G.H. Meads theory of subject (1934) later theorized by

Goffman in his drama-based conception of communication. Moreover, Goffmans

notion of figure is closely connected to LAAs subjective positioning processes,

seen as a fragment of the subject activated by and through discourse. At this

level, speakers have to deal with face-work strategies: Goffmans FTAs (facethreatening acts), formalized by Brown and Levinson (1987), FFA (face-flattering

acts), along with the notion of taxeme designed by Kerbrat-Orecchioni (1990,

1992, 1994, 1996) are helpful in formalizing phenomena at this level. We deal

with conquered or lost positions in relation to images built by co-speakers:

expert/non-expert, honest/dishonest, strict/lax; and more direct interactional

processes: confident/impulsive.

2.4 DISCURSIVE

P O S I T I O N I N G P RO C E S S E S

Discursive positioning processes mainly concern discourse structuration and

cognitive tasks brought into play by speakers, such as narration, argumentation,

description, explanation (Adam, 1992). Discourse can thus be segmented into

various moves or sequences, packages of utterances oriented towards the same

goal or strategy (Gumperz, 1982), sharing an inherent coherence. The way these

different sequences are chained together to form coherent discourse with a

specific communicative goal constitutes one of our main areas of investigation.

Following Austin (1962) and Searle (1969), authors such as Roulet et al.

(1992), Trognon and Brassac (1992) or Moeschler (1999) see discourse structure as a succession of speech acts, and refer thus to an illocutionary logic.

Discursive positioning processes allow us to conceive discourse as co-activities

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

294 Discourse Studies 7(3)

organized into a hierarchy. A description can be embedded in a narration, being

itself part of a persuasive sequence. These processes also enable subjects to construct and deconstruct unstable discourse balances, which produces a dynamic

vision of textual structure (Mosegaard-Hansen, 1998; Vion, 2000). At this level,

cognitive tasks are considered, corresponding to types of discourse and language

functions.

2 . 5 E N U N C I AT I V E

P O S I T I O N I N G P RO C E S S E S

Enunciative positioning processes concern purely enunciative phenomena and

lead the analyst to use the concept of enunciative staging designed by Vion

(1998a) to study how speakers stage themselves in their own speech and mark

their degree of involvement. Do they seem to speak alone, to be the only source of

their discourse or do they summon virtual speakers, creating built-in voices? In

order to make this clear, we need to distinguish between two enunciative orders:

speaker and source, in a polyphonic perspective inspired by Bakhtine (1984) and

Ducrot (1984). A given speaker is not necessarily the upstream source of his/her

utterance, he/she may just be a relay-speaker a mere physical speaking body

quoting from other peoples discourse, whether these people are identified, real

or not. The voices staged in speakers discourse will be referred to from now on as

utterers, in order to distinguish them from the physical speaker.

We also have to try to give an account of the different ways through which

speakers stage themselves in their speech to operate a meta-control, together

with the kind of modulation or footing which is achieved. Vions enunciative

staging typology offers a good starting point provided that it is agreed that an

utterance can be linked to different modes at the same time and that the typology

remains open. Moreover, it would be dangerous to expect a sequence to be composed only of utterances referring to just one mode such as unicity or duality.

Sequences are necessarily heterogeneously composed; therefore discourse activity cannot be reduced to a linear catalogue of successive enunciative staging acts

belonging to the same mode. Accordingly, Vion sees discourse linearity composed

of breaks or waves evoking the movement of breathing and thus speaks of

enunciative breathing. The five modes encompassing enunciative staging can

briefly be presented as follows:

1. Enunciative unicity: speaker builds an enunciative position which gives the

impression he/she is the sole master of his/her words.

2. Enunciative duality: speaker builds two positions. Utterances may thus

appear as ambiguous, implicit or opaque.

3. Enunciative parallelism: speaker stages several utterers and seems to speak

sharing their views.

4. Enunciative opposition: speaker stages several utterers and seems to go

against them.

5. Enunciative self-effacement: speakers voice seems to have deserted his/her

speech production.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 295

Within these five modes, sub-categories are made available by the collocation of

adjectives to identify data more clearly: polyphonic is used to refer to several

utterers, diaphonic to speaker and addressee, exophonic to speaker and an

absent utterer.

This set of tools introduced by Vion (1995, 1998a) follows up Goffmans

Forms of Talk (1981). The concept of footing has been set up to evaluate a

speakers involvement strategy in relation to a participation framework. This

notion has been discussed (Levinson, in Drew and Wooton, 1988; Lon, 1999)

and used in many ways. The positions sketched: animator, author, principal and

figure constitute a set which is coherent with the typology of enunciative staging

presented above. We may ask whether the position named figure belongs to the

same order as the other three. Lon (1999) presents Goffmans work, restricting

it to three positions instead of four, so does Schiffrin (1994). Clayman (1992)

introduces a new insight into the perspective, pointing to the part of responsibility which the addressee takes in influencing a speakers choice as to the position

assumed. Thus, discourse is clearly seen as co-constructed; monologal units are

then brought back into the interactional game, which is exactly what the LAA

team attempts to suggest.

Approaches allowing one to cross enunciative and discursive levels, connecting the utterance production axis with pragmatics are extremely rare. Doing so

casts a new light on certain markers or discourse particles (Schiffrin, 1987;

Fernandez-Vest, 1994; Aijmer, 1996; Mosegaard-Hansen, 1998). The star

model was designed to combine the two dimensions opening the door to enunciative integrative pragmatics. Likewise, Jeanneret (1999) clearly displays a similar

programme in the title of her book, whereas Verschueren (1999), negating the

existence of such an approach, establishes links between elements belonging

each to argumentative, illocutionary and cognitive orders. Our model enables

analysts to transgress strict interactional borders to deal with monologal texts

(Vion, 1999; Vion et al., 2001). The same goal has been present in the Geneva

School since the beginning (Roulet et al., 1985, 2001); as well as in Linell (1998)

and Nlkes research (1994; Nlke and Adam, 1999) and is one of the main

preoccupations of the LAA.

3. From theory to data

3.1

T H E S A JA M A C O R P U S

As part of a national research programme, we were asked to investigate the way

discourse is used in extreme situations to let speakers subjectivity emerge. A

group of 10 young male and female scientists volunteered for an expedition to an

18,000 ft summit in Bolivia named Sajama.

The expedition programme included 10 biological research protocols targeting human adaptation to the lack of oxygen (hypoxia) in high altitude, a frequent

cause of pulmonary oedema (Richalet et al., 1994). The study of verbal data

was also planned, in order to contribute to the understanding of psychological

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

296 Discourse Studies 7(3)

adaptation to extreme environment (Nol-Jorand et al., 1995; Blanchet et al.,

1997).

So, together with blood tests, subjects had to submit to audio-taped interviews

and self recordings before, during and after ascension. The recordings consisted

in telling the way they felt about the whole experience, the group and their own

reactions to the ordeal they were going through.

3.1.1 The impact of the institutional and modular levels

Even looking casually at the transcripts, it is quite clear that whether the subjects

face the tape-recorder alone or reply to the pre-established questionnaire read by

a member of the expedition, they actually are speaking to an absent addressee.

This absent addressee can be identified as the partially fuzzy representation they

have of the scientific authority that organized the expedition. This accounts for

the fact that subjects speech is linked to the image of what one should be and do,

according to the image they build of that fantasized authority and its expectancy,

rather than the spontaneous expression of their feelings; a discrepancy illustrating the combined influence of the institutional and subjective levels. The targeted

image (built for themselves and for others at the same time), is that of someone

worthy of the confidence placed in them and in their ability to cope with the

tasks they have been assigned. The situation also contains a paradox in the fact

that subjects are asked to give their feelings away whereas the institutional situation is far from favouring this. These facts point to the notion that the institutional setting drastically influences the way in which speakers express themselves.

At the modular level, we are led to consider that only one sub-type of interaction is present in the interviews: that of the questionnaire. The interviewer only

reads out the questions, refraining from giving any audible feedback, rephrasing

or eliciting reactions, which constitutes an additional obstacle for the emergence

of subjectivity. Nevertheless the corpus remains an interaction because discourse

is addressed and an interviewer is present, even if he does not appear to be the

main addressee.

There are interconnections between the setting and the discourse position as

well: when speakers are asked to describe the landscape surrounding them or to

talk about their arrival, we find that description and narrative sequences are

flawed with argumentative markers. Instead of hearing personal stories, we are

faced with self-justification. For instance donc (so) becomes twice as frequent for

one speaker, and three times as frequent for another speaker at times when they

try to conceal their suffering and pain.

It is also possible to show that the impact of the institutional setting weighs

deeply on involvement strategies, resulting in the particular balancing of enunciative staging modes. Despite the paralysing format of the situation, the pressure of the hostile conditions the subjects have to cope with entails enunciative

fluctuations in which overflowing subjectivity phases are immediately counterbalanced by the suddenly reappearing awareness of the general context, leading

to phases of rationalizing discourse.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 297

Two different reasons account for such a tendency to repress the outflow of

subjectivity: (1) each member of the expedition having to be up to the demands

of the extreme situation, they must take care of their image as we have already

indicated; (2) as we previously explained (Bertrand et al., 2000), too much

emotion, generally speaking, is an obstacle to the sharing of subjectivity, since it

lies in every communication and undermines it. Communication demands the

synchronization of emotional states, and therefore implies a certain degree of

distanciation.

3.1.2 Discursive and enunciative levels

3.1.2.1 Modalizing lexical choices

Accordingly, the use of puise (exhausted) to characterize a physical state by one

of the members of the expedition will be immediately modified and softened:

je me sens essentiellement puise + mais bon jespre que dans quelques jours + tout

sera rentr dans lordre

(I feel mostly exhausted + but well I hope that within a few days + everything will be

back in order)

The expression of subjectivity conveyed by puise (exhausted) is modalized by the

adverb essentiellement (mostly) and by the choice of je me sens (I feel) instead of je

suis (I am), and by a rationalizing discourse introduced by mais bon (but, well).

Mais (but) indicates that a counter-argument or at least a conflicting kind of discourse is about to follow; the particle bon (well) introduces a positioning shift

assigning a higher degree of relevance to the following statement. The presence

of mais (but) reminds us of the overall argumentative tonality underlying these

descriptive sequences.

As in the above-mentioned example, strong lexical choices as in: dcourage

(discouraged), inquite (worried) are usually corrected by modalizations: un peu (a

little), un certain (somewhat), un tout petit peu (very little) or followed by rationalizing clauses marked by particles mais (but), bon (well), mais bon ... confirming the

fact that too much exposure of self and feelings is not in good taste.

3.1.2.2 Polyphonic use of negation

In the same way, negative clauses can give rise to two different voices: (1) one

positive voice representing a potential or existing discourse; and (2) speakers

own voice denying the previous statement. For instance, negation in:

(2) Pour moi, a ne se passe pas trs bien

(For me, things are not going very well)

constitutes a form of moderating as compared with non-negative statement:

(1) Pour moi a se passe (trs ) mal

(For me, its going (really) bad)

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

298 Discourse Studies 7(3)

3.1.2.3 Enunciative swaying

Some subjects confront two different opinions in their own discourse, directly

staging two different voices: (1) one of the voices expressing their personal opinion; and (2) a second one opposed to it and allocated to the group or to the evaluating authority, or to some doxa. This somewhat basic form of polyphony is

frequent in one of the female subjects who uses it as a means of putting her own

discourse into perspective, so as to avoid excessive assertiveness in her frequent

phases of self-depreciation. Once again alternation of opinions (voices) is based

upon the use of the connective particle mais (but) which includes a spectacular

rise of its frequency:

je sens que++ je suis pas trs utile + que je peux pas vraiment au maximum+

mais je pourrais faire plus

mais de toutes faons y a pas grand-chose faire de plus + donc moralement je me

sens un peu inutile

I feel that ++ Im not being very helpful + Im not actually doing my best

but I could do better

but anyway there is not much more that could be done + so morally I feel kind of

useless

Statement (1) corresponds to speakers own voice; statement (2) stages other

voices, possibly referring to those of the group members; in statement (3) the

speakers voice is heard again, rephrasing her original opinion. It is notable that

moves (1) and (3) linked to the speakers opinion are considerably modulated

(sens que pas trs pas vraiment: feel that not very not actually; de toutes faons

pas grand-chose un peu: anyway not much kind of) in contrast to (2) in which

the voice of the group is staged. The same type of enunciative swaying is present

in one of the male subjects:

je me fous absolument.; (2) en fait cest faux (3) je mefforce (..): (1) I really dont give

a damn (2) in fact it is not true (3) but I do my best to (..)

3.1.2.4 About enunciative markers

As the expression of emotion is generally contained by subjects, we have to be

very careful in investigating verbal data to be able to spot the alternation of

phases of subjectivity and curbing utterances. Along with the modalizing of

strong lexical choices and the staging of alternate voices, the use of particles

such as ben, quoi, eh bien, bon, etc. can also reveal changes in the staging

strategies.

Markers such as eh bien (well) or bon (so) tend to point to rationalizing discourse whereas ben or quoi (you know) appearing at the end of utterances tend

to accompany self-centred sequences marked in higher subjectivity and lesser

share. Subjectivity sways would be relatable to enunciative phases shifting

between dramatization and trivialization, self-centredness and lack of focusing.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 299

Practically, rationalization discourse contains modalizers like vraiment (really),

videmment (obviously), en fait (in fact) or meta-enunciative comments such as

lets say that, a sort of and the use of pronouns like nous (we) or on (colloquial

for we in spoken French). Conversely, discourses in which subjectivity emerges

contain lexical choices which are inconsistent with the inter-subjectivity necessary for verbal exchange, and first-person pronouns.

In one given subjects speech, the distanciation of emotions reveals unexpected traces in his use of personal marks: in the Paris recordings, his use of je

(I) is conventional, and bears no emotional aspect. On the summit, an emotional

aspect is present but the form I is replaced by more impersonal discourse markers such as on (one) and a (that). More precisely, there seems to be a systematic

binary partition: je is used for positive emotions, whereas on is linked to the

negative ones:

(on scenery): within a five or ten meter distance + I like very much + but beyond that

one has great difficulty coping.

So negative aspects relate to others, and positive aspects are endorsed by the

speaker alone.

As for enunciative staging modes, explicit unicity corresponds to positiveness,

whereas parallelism or exophonic opposition is linked to negativeness.

On the summit, rather characteristically, in certain subjects speech, the

positive pole only is made explicit through the argumentative confrontation.

Enunciative moves generate and place in the foreground a negative implicit

counter-part. The speaker counter-argues positively facing an unspoken discourse which appears only through his counter-argument, revealed for instance

through the accumulation of quand mme (all the same):

a protective value, all the same, which exists in the group

Altiplano is all the same a very impressive thing

In another subjects speech, the same enunciative structure appears regularly.

This time, this marker activates a fictive addressee that the speaker tends to minimize or repress, here again producing a co-enunciation phenomenon.

3.1.3 Discussion

By comparing speech productions of subjects, whether in ordinary context or

under extreme conditions, we have been able to identify general tendencies

linked to high altitude and the effect of hypoxia (Vion et al., 2001), but also

personal characteristics such as differences in strategies or personality features.

For instance some subjects will resort to humour, whereas others will make use

of a certain rationalized discourse. Some subjects dramatized or self-centred

reactions result in isolation from the group and its lack of concern; other speakers, although in pain, do everything they can to cope rationally and to set aside

their own unease. Yet, personality features are partially neutralized by belonging

to the group and by the mission itself, so that the expression of emotions is

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

300 Discourse Studies 7(3)

constantly qualified, softened, broken, resulting in a rationalizing type of discourse or in surpassing oneself, which is more representative of the group than

of individual subjects.

3.2

THE MARSEILLES CORPUS

We are going to study a meeting which took place in a hospital in Marseilles

between a patient suffering from severe headaches (Mylne) and a member of

the medical staff (Sabine) in charge of handling an interview for a multidisciplinary research programme focused on the verbalization of pain.

3.2.1 The interactive frame

At the most general level, we first have to define the situation in which the verbal

exchange develops, i.e. establish a link between our corpus and one or several

types of interactions. In interactional studies carried out after Goffman, interaction types are defined according to the nature of the social relation that actors

settle. This relation expresses itself through positioning processes, interactional

goal, a degree of cooperation, the level of formality in turns and the way they are

handled. The first part of our meeting may then be defined as a medical interview, the goal of which is to build knowledge and not to diagnose or to deliver a

prescription. The complementary positioning process on which it dwells associates a patient giving information and a member of medical staff whose function

consists in collecting information in a way which is coherent with that goal. In

this particular meeting, presented in Appendix 1, the actors build a type of relation which is far more complex than that which is defined by the positioning

process constituting the situation. Besides, the co-construction process adds a

certain unpredictability to the development of discourse. It then appears necessary to make room for dynamic discourse activities shaped by actors endowed

with a certain power of action within a permanent interactive frame defining the

situation. As mentioned above, the interactive frame is defined by an institutional

positioning process whereas the interactive space, that is to say, the complex relation co-constructed by subjects implies a dynamic link between five types of positioning processes (institutional, modular, subjective, discursive and enunciative).

The definition of the communicative situation by the institutional positioning

process allows us to combine different successive interactions within a single

meeting, which more traditional definitions assimilating interaction to meeting

do not make possible. In the meeting which is dealt with here, it is possible to distinguish two successive interactions bringing together the same subjects. If the

first two extracts equate with an interview, what happens from line 91 and

onwards radically modifies the initial positioning process: Sabine (the doctor), on

learning that Mylne (the interviewed patient) works in the field of medical

research, completely modifies her attitude and within a few turns closes the

medical interview and opens a consultation for her own sake, enabling her to

consult the medical knowledge of Mylne (the patient). The initial positioning

process investigator/interviewee gradually yields to expert/non-expert, which

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 301

implies a reversal of high and low positions. Considering that Sabine indicates

that it is not at all in our interview when she initiates this new frame, considering also that the two subjects in presence never come back to the first medical

interview, it may be argued that the meeting is composed of two separate successive interactions, bringing together the same subjects, but in different social

relations and different frames (an interview and a consultation). We shall see

that at the level of the complex relation built by subjects (interactive space) the

second interaction develops in a particular climate, which is the natural followup to the interview.

3.2.2 The interactive space

After studying several interviews between a member of medical staff and a

patient asked to verbalize his/her pain, it was possible to confirm that the patient

orients his/her descriptions and narrations according to a thesis corresponding

to his/her personal diagnosis of the possible origins of the pain. Very often, this

personal diagnosis was contrary to the official medical diagnosis. The description of the pain, aimed at in the course of the interview, will be integrated into

an argumentative structure in which the patient will attempt to persuade his/her

partner. As the latter belongs to the medical field, the attempt is a tricky one.

The first interaction, the interview destined to produce knowledge, consists of

extracts 1 and 2, as well as the first lines of extract 3. If the institutional positioning process defining the interactive frame remains the same throughout the

interaction, the interactive space constantly modifies itself, even if two distinct

moments are identifiable.

Extract 1 (a module oriented towards discussion by Mylne)

In extract 1, Mylne will set up particular discursive positions, dwelling on the

argumentative component of language. She will then back her thesis (my

headaches are psychosomatic) with medical arguments:

I had a treatment both for the thyroid and the beginning of menopause. (line 4)

I had my eyes checked (. . .) so everything is all right. (1517)

I had already done a head scanner. (201)

X-rays have been done too to have a look at rhumatism (. . .). (212)

This argumentative sequence is integrated into the interview and compels

Mylne to take up the institutional position of patient. To convince her partner,

the activated interactional module will belong to the conversation order (symmetrical positions with a focus on content). At the enunciative level, Mylne

either endorses her own words using the first person pronoun (I, unicity mode) or

speaks with her doctors (enunciative parallelism):

So I came to consult Doctor B / Weve done /weve spoken a lot to try to see if there

was no problem. (1315)

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

302 Discourse Studies 7(3)

one could / could have believed this to be the cause. (19)

weve done x-rays to see a little. (21)

well we found small things. (24)

At the enunciative level, the activated positions alternate between unicity and

enunciative parallelism but also have self-effacement brought into play. This mode

allows the speaker to present discourse as objective and as a general authoritative

opinion:

Because the treatments for Menopause, its always with hormones and it always

favours headaches. (79)

The notion of authority initiated by the enunciative parallelism mode, one voice

of which is part of the medical order; as well as the universal truths deriving

from the use of the effacement mode enhances the impact of the speech that the

patient endorses then more directly. As for subjective positions, Mylne presents

the image of a rather expert person who possesses a sort of medical knowledge.

Not only does she argue, eliminating gradually all the possible organic causes of

her headaches, but, as we have just seen it, she asserts some medical knowledge,

notably about the secondary effects of menopause treatments. The overall study

of interrelated positions allows analysts to cast light on subjects activities and

strategies. After the analysis of this first sequence we can make a certain number

of points:

1. Mylne apparently accepts the position of patient-informer, which helps to

define the complementary frame of the interview. Also, she has no choice, if

a subject refuses the positioning process defining a specific frame, communication is completely blocked and nothing would be constructed until some

kind of frame was found and accepted by participants.

2. While accepting the starting frame, Mylne, through her play on other positions, modifies the institutional process: wanting to initiate a conversation

module, taking up the attitude of an expert, setting up arguments and

playing on enunciative positions which endows her with a certain authority

and leads her to play higher than expected on the institutional process of

information giver.

We will not go as far as to assert that this lack of consideration towards the investigator because of an immodest play would account for Sabines refusal to take

the argued thesis (my headaches are psychosomatic) into account. This refusal is

nonetheless clear-cut:

Why psychosomatic? its not because the CAUSE is not KNOWN (laughter) that necessarily there is no cause. (323)

Extract 2 (module oriented towards conversation by Mylne)

In this second part of the interview, Mylne is radically going to change strategy

and then continue her persuasion work in another manner. Although she is a

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 303

researcher in the medical field (which Sabine will learn only at the end of the

interview), she pretends not to know medical terms directly concerning herself.

They found something there, which shrinks, I dont know the name (laughter).

(345)

Beside the fact of stating her ignorance which consolidates Sabine in her position

of expert, the peal of laughter seems to have a very complex function: infantilize

at the subjective position level and it is also an attempt at setting up a form of

complicity and proximity (modular level), enunciative distanciation, etc. The

same configuration appears just after that:

thats it (laughter) / its / they are terms that I generally forget, hah. (412)

A subtle analysis should also take into account the production of hein (hah) as a

discourse marker. The interview becomes more dialogical with consistently

longer turns from Sabine. This general configuration will then gradually engender a conversation module with enunciative positions linked to duality and

humour. This is what is noticeable when speaking about her weight, Mylne

says:

then may be also by the ... important mass. (56)

The lexical choice of mass (volume) implies an enunciative distanciation and a

play in the act of stating. This self-derisive humour accompanied by a little laugh,

which seems to be targeting a feminine complicity, illustrates the radical modification of Mylnes positioning. All the more so if one considers that instead of

producing an argumentation, at the subjective positioning level, she will make do

with the setting up of a narration by which she tells herself. The dual enunciative

play identified on mass will carry on with the expression tir group (shooting

party; line 64) to talk about a set of analyses already done and will be found later

on:

I started losing a bit of weight, but well, its not ... that brilliant. (701)

As we have indicated, this sequence is not based on direct argumentation but

rather on a narration-description component which develops into a long monologue (lines 6572). This type of narration functions as an argument in a

discourse which bears a persuasive goal. Its interest lies in the fact of arguing

implicitly, without risking offending the partner, showing a sort of knowledge in

keeping with the position of expert.

In the course of this module oriented towards conversation, one notes that

cooperative complicity gradually invades Sabines speech in such a way that the

two women finally manage to coordinate their laughter (lines 756). Such coordination does not appear anywhere else; Mylne ends the narration with an

utterance bearing argumentative echoes:

and::::::::::::: then I had to have my teeth operated on and the headaches came back

(low) of course (laughter). (745)

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

304 Discourse Studies 7(3)

The voice volume drop evoking confidential talk, the use of the style of speaking

adverb (of course) and laughter clearly mark a positioning, which, on the subjective side, targets complicity and proximity. After this second sequence, Sabine

agrees to take into account Mylnes own thesis. It is not possible to evaluate

Sabines degree of acceptance but it seems difficult to disassociate this concession

from all the interactive play on various positioning processes.

A few points have been given here and doubtless the analysis must be carried

further. It would also be necessary to take into account the different pauses

which precede marked lexical choices, hesitation structures (and the moments

when they occur in discourse), breaks and incomplete utterances, modalizations

(anchoring of discourse in fictive, real or fantastic worlds), modulations (distanciation strategies bearing on the act of discourse), rephrasing strategies, metadiscursive commentaries, turn overlaps, discourse markers, etc. (all the various

traces of language activity which generally constitute the basis of the analyses

carried out by the LAA team).

Also, a linguist is less concerned with the efficiency of strategies than with

the analysis itself. It is of little interest whether Mylnes strategies allow her to

achieve her goal or not. Strategies are coordinated lines of action that must be

described using linguistic concepts first. Interactive strategies would then depend

on the particular way subjects play this complex game of positioning processes.

The different strategies: intimidation, persuasion, kow-tow, seduction, research

of success, competition, minimal involvement, consensus reaching, etc. could

then be visualized by specific configurations of plays on those various positions.

Extract 3 (consultation)

As mentioned above, as early as line 97, a second interaction appears: Mylne

becomes the expert that Sabine consults. Given the fact that a certain interactional complicity was initiated earlier, Mylne will have to act modestly in the

position of expert, just as Sabine was doing in the preceding interaction. If the

interactive frame is altered, the relational history woven in the course of the first

interaction will continue in the second one. As a result, Mylne who, in the

course of the interview, had partially managed to initiate a conversational

module playing on complicity and proximity will develop her role of expert, by

hesitating in her speech and trying to avoid a structured aspect. These hypercorrection phenomena are probably explainable by the modesty law, according

to which one must not let ones face be exalted excessively nor a fortiori exalt it

oneself (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 1996).

In other situations, they can also reflect the difficulty that a subject feels when

speaking about his/her profession to partners who do not have a very clear idea

of it. Here are other examples of the hypocorrection phenomena:

hesitation structures: euh (huh) 16 occurrences in five short monologues.

qualifiers such as:

To put it that way (100, 102),

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 305

that kind of thing (113),

that kind of problem (100).

simplified and ordinary syntactic forms:

this is very molecular biology (106)

at the chromosome level (1067)

numerous modalizers which blur Mylnes positioning:

simply (101), rather (102,103,107), quand mme (even so, come on), (108).

3.2.3 Discussion: heterogeneity and instability of units

The analysis of this meeting enabled us to discuss different types of phases:

interactions, when distinct interactive frames follow one another; modules when

interaction types are developed locally; and sequences when discourse activity

types are linked to cognitive discursive tasks. Other smaller units also exist:

exchanges, interventions, turns, speech acts and utterances.

Whatever the type of unit considered, it is necessary not to adopt a simplistic

conception of the overall structure seen as a mechanical construction of homogeneous units. In certain cases it will be possible to identify the beginning and

the end of a conversational module in a specific interactive frame, when the two

subjects cooperate narrowly. However, a difference in availability of subjects for

the setting of a conversational module will inevitably lead to complex situations.

In extract 2, Mylne struggles to initiate a conversational module in the interview (constituting the interactive frame of the meeting) through lexical choices,

enunciative positionings and the use of narration-description sequences. Sabine,

on the contrary, will resist this invitation, restricting herself to a production of

discursive forms closer to interview than conversation. At this particular point,

we have a structuration conflict which can persist because it does not directly

affect the institutional positionings defining the interactive frame. However, as

Mylne continues her attempts, Sabines utterances move closer to a conversational involvement. The coordination of peals of laughter, the expression of complicity and accepted togetherness sketch a conversational attitude subordinated

to the position of investigator. It then becomes clear that the question concerning

units is complex: for Mylne, we can identify an attempt to initiate a conversational module, whereas for Sabine, there is an evolution towards a form of

conversational communication but the line is never really crossed. In such conditions, the conversational module which should concern both co-participants is

very difficult: the two subjects tend towards it according to different rhythms but

do not reach a conversational level. However, this orientation towards a conversational order is obvious in extract 2, all the more so by comparison with Sabines

limited interventions in extract 1. Discourse is never constituted of stable and

homogeneous units, which would appear in order, one after the other. In different interventions, the same conversational module can take up various forms,

just as a certain text type such as narration can take very distinct forms depending on the discourse genres in which it is integrated (literary works, narration of

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

306 Discourse Studies 7(3)

ordinary life, fairy tales). Within a unified theoretical approach we assimilate the

notion of interactive frame to that of verbal interaction genres as well as that of

discourse genres.

Not only the same unit will take up a very different form depending on the

frame in which it is produced, but also, depending on the activity of subjects at

the level of the interactive space. The units used will then be taken at different

levels of their achievement (it is then possible to draw a link to Glich and

Quasthoff s narrativity degrees (1985) and Adams prototypical logic (1992)).

Beside the complexity deriving from the compositionality of units and the

action of subjects, structuration conflicts between various participants will

constitute a supplementary factor of heterogeneity and instability of units. This

is what we can see with discussion (extract 1) and conversation (extract 2).

Given the constraints linked to the frame, these modules cannot become stable in

the interview. This is obvious in both cases by Sabines reluctance to go too far in

the activation of such modules. However, considering that Mylne struggles to

set them up and that Sabine must show she is cooperative, the orientation

towards these modules remains important, even if neither of them will be fully

activated. We will have to posit that distinct degrees of activation are possible for

discourse units in relation to the configuration of the interactive frame and

structuration conflicts occurring between participants.

4. Conclusion

The star model, by permitting scrutiny of the various levels of verbal communication, makes possible the fact of putting heterogeneous phenomena into a

structuring perspective. It is true that psychological or sociological factors which

influence individuals are complex and numerous, but as such they do not belong

to our scope of investigation. The interest of the linguistic approach we defend

lies rather in the attempt to bring to light the way in which levels as varied as

institutional, modular, subjective, discursive and enunciative positioning

processes must be taken into account to produce an analysis concerned with

social practices as well as micro-linguistic strategies.

The attitude of subjects towards language productions evolves in such a way

that the development of discourse will be characterizable by discourse breaks

and a relative enunciative instability.

The interest of the model presented here lies in the attitude, apparently paradoxical, of presenting concepts analysing discourse from clear-cut categories

while focusing on instability, heterogeneity and the dynamism of discourse

strategies.

A P P E N D I X 1 T H E M Y L E N E / S A B I N E I N T E RV I E W,

15

JUNE

1992

M = Mylne: patient (and a medical researcher at the INSERM, a professional status

Sabine is not aware of during the first part of the interview)

S = Sabine (doctor in charge of the interview)

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 307

Excerpt 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

(...)

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

et puis euh:::: depuis dj:: pas mal dannes je souffre de migraines /

cest pour a que je suis venue voir euh le Docteur B. / parce que

(1,59) le dernier trimestre de lanne dernire euh:: (0,98) jtais en

(+) traitement et pour la thyrode et pour un dbut de mnopause

puisque jai 46 ans (+)

hm hm

et je sais pas si ce sont ces mdicaments associs / parce que les

traitements pour la mnopause cest toujours sous forme dhormones

et a favorise toujours (+) les migraines

mm=

euh jai eu des migraines atroces cest--dire que je me retrouvais

par terre euh::: oblige de faire venir le SAMU / euh::: enfin videmment un stade trs trs (1,07) / donc je suis venue consulter M. B.

euh (1,15) on a fait / on a parl pas mal pour essayer de voir si y

avait pas de problmes / Jai fait un examen des yeux (++)

hm oui pour chercher une cause

pour savoir euh:: sil y avait quelque chose / donc cest normal /

comme aussi javais eu des problmes de diabte et que ma mre

est diabtique donc on pourrait / on aurait pu croire a / euh jai

javais dj fait un scanner (+) euh de la tte donc je savais quy avait

rien dimportant / ts hm on a fait des radios pour voir un peu euh au

point de vue euh rhumatisme

si on avait (xxxxxx)

bon (+) l il y a un petit quelque chose / il y a un pincement / enfin on

a trouv des des petites choses qui peuvent euh (1,80) tre une

petite part de (+) de ces douleurs

hm hm

Notamment un effet de torticolis que jai / quelque chose qui ressemblerait a de gne pour euh tous les mouvements (+) mais::::

(soupir) (1,59) je crois aussi que le / la migraine cest:::: (bas)

psychosomatique (rire) et que::::::://

(rapide) pourquoi psychosomatique cest pas parce quon ne

connat pas la cause (rire) que forcment il faut dire quy en a pas

Excerpt 2

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

ils ont trouv quelque chose l qui se rtrcit dont je sais pas le

nom (clat de rire)

oui dans le bras (xxx)

oui=

cause des ctes?

d:::fil::::tracho-brachial

tracho-brachial?

cest a oui (rires) / cest des / ce sont des termes que joublie

gnralement hein

thoraco-brachial: hein

thoraco-brachial

oui parce que la trache elle est loin quand mme hein / Cest l

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

308 Discourse Studies 7(3)

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

(...)

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

(...)

82

83

84

85

(...)

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

S

M

S

quand vous levez les bras vous avez des (++)

oui::: jai / je

des sensations mm

oui si je porte un poids qui est / qui moblige faire a je peux plus

euh::

hm hm

jai limpression que tout le bras

oui ce sont les artres qui sont un peu coinces par la pre/

voil

mire cte

puis aussi peut-tre par le (+) volume (rire) important

vous pensez que

euh donc euh euh pour continuer ce qui a t fait donc (++) euh::

(1,63) t / je suis alle consulter ch:::::::::ez le Professeur V

oui

aussi pour euh voir //

pour le diabte toujours?

les problmes de diabte de poids de thyrode enfin (+) pour faire

un group euh un tir group

oui javais dj fait un:: traitement mais ctait peut-tre pas assez

quilibr (+) l jai refait les examens et::: (+) et puis euh::: je prends

je reprends des hormones du 13me au 25me jour des rgles (+)

pour essayer aussi de de compenser un peu le / les problmes hormonaux / Pour le diabte cest / a a lair / tout fait quilibr /

bon l jai commenc un peu perdre du poids mais enfin cest

cest pas folichon cest dire cest trois kilos depuis euh / bon enfin

a fait pas longtemps non plus (1,51)

mm

et:::: l je dois me faire oprer des dents et la migraine elle est

revenue (bas) videmment (rire)

(rire)

donc cest pour a que je dis que cest trs //

vous pensez que le

psychosomatique

comment vous lprouvez cette douleur vous pouvez me la dcrire

un petit peu (++) mme la caractriser (+) essayer dimaginer (++)

vous pensez vous quil y a un problme euh

oh oui

psychosomatique important / vous pensez que a correspond a

corresponde des problmes dans votre vie l o (...)

Excerpt 3

86 S

87 M

88

89

90 S

cest vrai quand on est soumis des stress ou des responsabilits on ++

oui oui oui mais bon je crois pas parce que quand mme la profession cest une

habitude / cest pas ds maintenant que je suis ++ / a fait 25 ans que je travaille

+ je veux dire bon

vous travaillez dans quelle +

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 309

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

S

M

je travaille lINSERM la recherche mdicale

oui

sur les rcepteurs / cest fond/ cest de la recherche fondamentale

mais a mintresse / jai + / a fait euh / jai une matrise dhistologie gnrale

et jai fait un peu de

euh sur le

de biochimie / cest pas du tout dans notre entretien

euh sur le euh euh rcepteur euh lantigne / cest--dire euh les fonctions

euh alpha bta et gamma delta euh et les relations avec euh les complexes Cb3,

Cb4, Cb8 / enfin ce genre de problme / enfin si vous voulez

vous tes biologiste au dpart

je suis chim / aide-chimiste au dpart / mais si vous voulez cest plutt euh /

je travaille plutt dans le problme de la structure + de lanalyse germinale

euh de ces gnes qui conduisent

XX

donc cest trs biologie molculaire et structure euh au point de vue

chromosomes euh cartographie des gnes euh / plutt de ce ct de ltude

donc dun point de vue plus biochimique que mdical quand mme

euh ni chimique ne mdical + trs fondamental

trs fondamental

simplement euh pour pouvoir construire des gnes les mettre dans des

cellules eucaryotes et voir euh lexpression si on apporte des mutations

ce genre de choses

daccord non a mintresse beaucoup parce que en mme temps que mes

tudes de mdecine jai fait plusieurs CES dhistologie embryologie parasitologie

APPENDIX

TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

:

/

//

+

(1,51)

(xx)

=

(laughs)

underscored

CAPITAL LETTERS

APPENDIX

the immediately prior syllable is prolonged. The number of colons is

proportional to the prolongation

self-interruption

interruption or overlapping by an interactant

pause: the number of + increases with the duration of the pause

exact duration of the pause

what has been uttered is uncertain

no time elapses between utterances

description of aspects of paraverbal or nonverbal behaviour

uttered simultaneously

stressed syllables

T R A N S L AT I O N S O F F R E N C H T E R M S

balancement nonciatif

connecteurs

discursive

enonciatif

espace interactif

marqueurs structurels

place (ralisee)

place institutionnelle

alternating voices/enunciative swaying

connective discourse particles

discursive

enunciative

interactive space

pattern markers

position

institutional positioning

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

310 Discourse Studies 7(3)

place modulaire

positionnement

positions sociales

rapport de place

relation contracte

relation interlocutive

relation interpersonnelle et sociale

rles

subjective

modular positioning

positioning

social positions

(interrelational) positioning process

contracted relation

interlocutive relations

interpersonal and social relations

roles

subjective

AC K N OW L E D G E M E N T S

This research was funded by the Ministre National de la Recherche et de Technologie,

Programme COG13B, ACI Cognitique. Corpora are the property of the Dpartement de

Biomathmatiques, Statistiques et Informatique, Facult de Mdecine, Marseille: The

Sajama Corpus, and of the LAA team: The Marseilles Corpus.

REFERENCES

Adam, J.-M. (1992) Les Textes: Types et prototypes. Paris: Nathan.

Adam, J.-M. (1997) Le Style dans la langue. Paris: Delachaux et Niestl.

Adam, J.-M. (1999) Linguistique textuelle. Des genres de discours aux textes. Paris: Nathan.

Aijmer, K. (1996) Conversational Routines in English. Harlow: Longman.

Amossy, R. (ed.) (1999) Images de soi dans le discours: La construction de lethos. Lausannne:

Delachaux et Niestl.

Austin, J. (1962) How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bakhtine, M. (1984[19523]) Esthtique de la cration verbale. Paris: Gallimard, Coll N.R.F.

Bell, A. and Garrett, P. (eds) (1998) Approaches to Media Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell.

Berthoud, A.C. (1996) Paroles propos: Approche nonciative et interactive du topic. Gap:

Ophrys.

Bertrand, R. et al. (2000) Lobservation et lanalyse des affects dans linteraction, in

C. Plantin, M. Doury and V. Traverso (eds) Les motions dans les interactions, pp.

16982. Lyon: ARCI.

Blanchet, A., Noel-Jorand, M.C. and Bonaldi, V. (1997) Discursive Strategies of Subjects

with High Altitude Hypoxia: Extreme Environment, Stress Medicine 13: 1518.

Brmond, C. (2003) La porte co-nonciative de bon: Son rle dans la structuration de

lobjet discursif , Revue de Smantique et de Pragmatique 13: 923.

Bronckart, J.-P. (1996) Activit langagire, textes et discours. Lausanne: Delachaux et

Niestl.

Brown, P. and Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clayman, S.E. (1992) Footing in the Achievement of Neutrality: The Case of NewsInterviews Discourse, in P. Drew and J. Heritage (eds) Talk at Work: Interaction in

Institutional Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Drew, P. and Heritage, J. (eds) (1992) Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Drew, P. and Wooton, A. (eds) (1988) Erving Goffman: Exploring the Interaction Order.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ducrot, O. (1984) Le dire et le dit. Paris: Les ditions de Minuit.

Fairclough, N. (1989) Language and Power. London: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1995) Media Discourse. London: Edward Arnold.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 311

Fairclough, N. (2000) New Labour, New Language. London: Routledge.

Fernandez-Vest, J. (1994) Les Particules nonciatives. Paris: PUF Linguistique Nouvelle.

Foucault, M. (1984) The Order of Discourse, in M. Shapiro (ed.) Language and Politics,

pp. 10338. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ghiglione, R. (ed.) (1989) Je vous ai compris ou lanalyse des discours politiques. Paris:

Armand Colin.

Ghiglione, R. and Charaudeau, P. (eds) (1999) Paroles en images, images de paroles, trois

talk-shows europens. Paris: Didier Erudition.

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1963) Behavior in Public Places. New York: Free Press.

Goffman, E. (1967) On Face Work, in Interaction Rituals, p. S46. New York: Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1971) Relations in Public. New York: Basic Books.

Goffman, E. (1974) Frame Analysis. New York: Harper and Row.

Goffman, E. (1981) Footing, in Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Glich, E. and Quasthoff, U.M. (1985) Narrative Analysis, in T.A. Van Dijk (ed.) Handbook

of Discourse Analysis 2: Dimensions of Discourse. New York: Academic Press.

Gumperz, J. (1982) Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halliday, M. (1973) Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. and Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Jeanneret, T. (1999) La Cononciation en franais: Approches discursive, conversationnelle et

syntaxique. Berne: Peter Lang, Sciences pour la Communication.

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (1990, 1992, 1994) Les Interactions verbales, vols 1, 2 and 3. Paris:

Armand Colin.

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (1996) La Conversation. Paris: Seuil.

Lon, J. (1999) Les Entretiens publics en France: Analyse conversationnelle et prosodique. Paris:

CNRS ditions.

Linell, P. (1998) Approaching Dialogue: Talk, Interaction and Contexts in Dialogical

Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Livingstone, S. and Lunt, P. (1994) Talk on Television, Audience Participation and Public

Debate. London: Routledge.

Maury-Rouan, C. (1998) Le paralllisme co-nonciatif: Construire plusieurs lallocutaire absent: lnonciateur en creux dans le dialogue, Les Registres de la Conversation,

Revue de Smantique et Pragmatique 3: 14558.

Maury-Rouan, C. (2001a) LHypocorrection: Entre sociolinguistique et analyse linguistique des interactions, in Lengua, Discurso, Texto, pp. 162738. Madrid: Visor Libros.

Maury-Rouan, C. (2001b) Le flou des marques discursives est-il un inconvnient? Vers la

notion de leurre discursif , online journal, Marges Linguistiques 2: 16376

(http://www.Marges-linguistiques.com).

Maury-Rouan, C. (2003) Discourse Particles as Interactional Lures, GURT 2002 (IVth

Georgetown Roundtable on Language and Linguistics), Georgetown University,

Washington, DC, 1517 February.

Mead, G.H. (1934) Mind, Self and Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Moeschler, J. (1999) Thorie pragmatique et pragmatique conversationnelle. Paris: Armand

Colin.

Mosegaard-Hansen, M.B. (1998) The Function of Discourse Particles: A Study with Special

Reference to Spoken Standard French. Amsterdam: Benjamin.

Nol-Jorand, M.-C., Reinert, M., Bonnon, M. and Therme, P. (1995) Discourse Analysis

and Psychological Adaptation to High Altitude Hypoxia, Stress Med 11: 2739.

Nlke, H. (1994) Linguistique modulaire: De la forme au sens. Paris: Bibliothque de linformation grammaticale, ditions Peeters.

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

312 Discourse Studies 7(3)

Nlke, H. and Adam, J.-M. (eds) (1999) Approches modulaires: De la langue au discours.

Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestl.

Priego-Valverde, B. (1998) Lhumour (noir) dans les conversations: Jeux et enjeux, Les

Registres de la Conversation, Revue de Smantique et Pragmatique 3: 12344.

Priego-Valverde, B. (2001) Cest du lard ou du cochon? Lorsque lhumeur opacifie la conversation familire, online journal, Marges Linguistiques 2: 195208 (http://www.

Marges-linguistiques.com).

Priego-Valverde, B. and Maury-Rouan, C. (2003) La mise en mots de la douleur, in J.M.

Colletta and A. Tcherkassof (eds) Perspectives actuelles sur les motions: Cognition,

langage et dveloppement. Brussels: Hayen, Mardaga.

Richalet, J.P., Souberbielle, J.C., Antezana, A.M., et al. (1994) Control of Erythropoiesis in

Humans during Prolonged Exposure to Altitude of 6,542 m, American Journal of

Physiology 266: R556R764.

Roulet, E. et al. (1985) LArticulation du discours en franais contemporain. Berne: Peter Lang.

Roulet, E. et al. (1992) Actes de langage et structure de la conversation, Cahiers de

Linguistique Franaise 13: 76107.

Roulet, E., Filliettaz, L. and Grobet, A. (2001) Un modle et un instrument danalyse de lorganisation du discours. Berne: Peter Lang.

Rouveyrol, L. (1998) Vers une stylistique de linteraction tlvise?, Bulletin de la Socit

de Stylistique Anglaise 19: 944.

Rouveyrol, L. (1999) Pour une stylistique du taxme dans le dbat politique tlvis:

Analyse de quelques rseaux interactionnels signifiants, Asp 23/26: 99120.

Scannell, P. (ed.) (1991) Broadcast Talk. London: Sage.

Schiffrin, D. (1987) Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schiffrin, D. (1994) Approaches to Discourse. London: Routledge.

Searle, J. (1969) Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (1990) Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tannen, D. (1989) Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational

Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trognon, A. and Brassac, D. (1992) LEnchanement conversationnel, Cahiers de

Linguistique Franaise 13: 76107.

van Dijk, T. (1998) News as Discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Verschueren, J. (1999) Understanding Pragmatics. London: Edward Arnold.

Vion, R. (1992) La Communication verbale: Analyse des interactions. Paris: Hachette.

Vion, R. (1995) La Gestion pluridimensionnelle du dialogue, in Cahiers de Linguistique

Franaise 17: 179203.

Vion, R. (1998a) La Mise en scne nonciative du discours, in B. Caron (ed.) Proceedings

of the 16th International Congress of Linguists (CD-ROM). Oxford: Elsevier Sciences.

Vion, R. (ed.) (1998b) Les Sujets et leurs discours: Enonciation et interaction. Aix-enProvence: Publications de lUniversit de Provence.

Vion, R. (1998c) De linstabilit des positionnements nonciatifs dans le discours, in

J. Verschueren (ed.) Pragmatics in 1998: Selected Papers from the 6th International

Conference, vol. 2, pp. 57789. Antwerp: International Pragmatics Association.

Vion, R. (1999) Pour une approche relationnelle des interactions verbales et des discours, Langage et Socit 87: 95114.

Vion, R. (2000) Les Activits de recadrage dans le droulement discursif , in E. Nemeth

(ed.) Pragmatics in 2000: Selected Papers from the 7th International Prgamatics Conference,

vol. 2, pp. 58397. Antwerp: International Pragmatics Association.

Vion, R. (2001a) Modalits, modalisations et activits langagires, online journal,

Marges Linguistiques 2: 20931 (http://www.Marges-linguistiques.com).

Downloaded from dis.sagepub.com by Sara Lima on September 25, 2010

Rouveyrol et al.: A linguistic toolbox for discourse analysis 313

Vion, R. (2001b) Effacement nonciatif,et strategies discursives, in A. Joly and M. de

Mattia (eds) De la syntaxe la narratologie nonciative (Textes recueillis en homage Ren

Rivara), pp. 3314. Paris: Ophrys.

Vion, R. (2003) Modalisations et modalits dans le discours, XVIIme congrs international des linguistes, Prague, juillet 2003, in Actes (CD-ROM). Oxford: Elsevier.

Vion, R., Burle, E. and Rouveyrol, L. (2002) De linteraction au texte littraire, transgression dun modle du genre, in E. Roulet Les Analyses de discours au dfi dun dialogue

romanesque, pp. 46981. Nancy: Presses Universitaires de Nancy.

Vion, R., Rouveyrol, L., Maury-Rouan, C., et al. (2001) Outils linguistiques pour lanalyse

du discours et des motions, Revue Franaise de Psychiatrie et de Psychologie Mdicale

V(49): 4956.