Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Agón or Certamen

Încărcat de

Javi LoFriasTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Agón or Certamen

Încărcat de

Javi LoFriasDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

ISSN 2348-3156 (Print)

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN 2348-3164 (online)

Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp: (101-105), Month: July - September 2015, Available at: www.researchpublish.com

Agn or Certamen? A Philosophical Analysis of

the Greek-Roman Agonistic Paidia and Its

Influence on the Conception of Contemporary

Sports

Emanuele Isidori1, Francisco Javier Lpez Fras2, Rafael Ramos Echazarreta3

1,2,3

Laboratory of General Pedagogy, University of Rome Foro Italico, Italy

Abstract: In ancient Rome, Greek agnes were never widespread. This is evidenced by the fact that the word agn

never actually found a counterpart in the Latin language. Instead, the Romans used the term certamen, which does

not have the same exact meaning as the Greek word it replaces. In Rome, certamina were mostly considered

performances in which the athlete was nothing more than a performer-actor (or actress, because some authors talk

about women who appeared in struggles and competitions fighting other women) and not an athlete in the strictest

sense. Participants in certamen were often criminals and thugs (or prostitutes). They competed in the stadium

during the day and were hired to carry out killings in some slum of the city at night. Using this historical

background as a starting point, the purpose of this study is to identify the philosophical bases of the Roman

certamen system and to compare them with those of the Greek agonistic system. The Latin word certamen

relates to the idea of earning the approval of a crowd by prevailing in a fight against others who are considered as

enemies (the concursus). From a philosophical point of view, the word certamen refers to conceptual, political,

educational, and aesthetic categories completely different from those of the Greek agn. The concept certamen

refers to an individualistic dimension not communitarian of aesthetic, visual, and communicational attributes

which can also be found in contemporary sports. By using a philosophical hermeneutic approach, and by making a

comparison between the Greco-Roman athletic paidia and contemporary sport, we argue that, first, in the

conceptual history of sports there has always been a tension between the two philosophical and ethical poles

represented by agn and certamen. Second, we argue that this tension can also be found in the conception of

contemporary sport. To conclude, we argue that by understanding the agn-certamen couple, one can arrive at a

clearer and less reductive interpretation of both the main philosophical and cultural meanings of contemporary

sports and the pedagogies by which, nowadays, sports are inspired.

Keywords: agn, certamen, hermeneutics, education, contemporary sports.

I. INTRODUCTION

The main goal of our study is to demonstrate that the contemporary sport culture has been influenced by two conceptions

of competition whose roots can be found in Greek and Roman culture. These two notions of competition are: agn and

certamen (whose plural nouns are agones and certamina, respectively). The history of both Greek-Roman sports and

modern-day sports can be explained by using the conceptual couple agn-certamen. However, this is not a work in sport

history. Rather, we look at ancient and contemporary sports through a philosophical lens. In so doing, we reflect, by

means of a hermeneutic method, on how ancient philosophy of sport and philosophy of physical activity influences our

conception of sport. Our hermeneutical analysis of ancient sports has a practical aim, which is to understand how to apply

the main values found in ancient sports to the arena of sports education in order to better our sporting world.

Page | 101

Research Publish Journals

ISSN 2348-3156 (Print)

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN 2348-3164 (online)

Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp: (101-105), Month: July - September 2015, Available at: www.researchpublish.com

In so doing, we assume that, despite all the apparent cultural ruptures that occurred in the Middle Ages, there is a clear

continuity between ancient sports and contemporary sports; both eras are part of the same historical continuum since they

share some key components and ideas that we highlight in this work. In fact, we employ a hermeneutical methodology

because hermeneutics is the philosophical approach that most emphasizes the embeddedness of all our ideas and practices

within tradition:

A reflection on what truth is in the human sciences must not try to reflect itself out of the tradition whose binding force it

has recognized. Hence, in its own work, it must endeavor to acquire as much historical selftransparency as possible. [I]t

has to try to establish a new relation to the concepts which it uses. It must be aware of the fact that its own understanding

and interpretation are not constructions based on principles, but the furthering of an event that goes far back. Hence, it

will not be able to use its concepts unquestioningly, but will have to take over whatever features of the original meaning

of its concepts have come down to it (Gadamer, 1978, p. xxiii).

Gadamers rehabilitation of tradition as a necessary philosophical category helps us reinterpret modern-day sports by

linking them to both their ancient cultural roots and their social and cultural context. After all, according to Gadamer, we

need to understand the original meanings of the concepts we use and learn how they have come down to us in order to go

beyond them. Our contemporary conception of sports has not been created in a void, but rather it is a blend of ancient

philosophical ideals, modern principles, and our circumstance as citizens of modern liberal-democratic societies. Should

we want to better our sporting world, we first need to understand its philosophical, cultural, and social foundations.

Generally speaking, three main differences are identified as key to distinguish between Greek sports and their Roman

counterpart. The first difference is that whereas Greek sports were regarded as contests and as intrinsically related to play,

in Rome, sports were conceived of as games. Second, participants in Greek sports were free men, whereas slaves starred

in Roman sporting contests. Third, in Greece, sports were an integral part of the educative system, while in Rome, they

were part of a superficial culture of spectacle and violence. The three key differences between Greek sports and Roman

sports are partly correct and partly incorrect. We explain why this is so in what follows.

II. THE PROBLEMATIC INTRODUCTION OF THE GREEK AGONISTIC SPIRIT IN ROME

Greek agones were not widespread in ancient Rome. For example, there is no Latin counterpart of the Greek word

agn. Romans used the term certamen to refer to the Roman athletic contest, which has a meaning different from that

of the Greek word agn. Only Cicero, creator of the literary and philosophical language of Rome, used the term

certamen with the same meaning as the Greek word agn. For Cicero, like the Greeks, the term certamen referred to a

competition or a contest that involved a physical confrontation between bodies. In contrast, for Roman authors such as

Livy or Quintilian, certamen had a meaning related to war and battle. Certamen, understood from the perspective of the

concepts of war and battle, is a duel in which two people have a confrontation. Certamen is part of a battle (pugna), which

is, in turn, a part of the war (bellum).

The word certamen comes from the Latin verb cernere, which means: to consider, to measure, to compare, and to think

about something carefully before making a decision or developing an opinion. All of these meanings come down to the

idea that certamen is related to the careful assesment of a situation, person, or problem in order to make a judgment. In the

case of certamen, the situations, the people, and the problems that need to be assessed are related to deciding, in terms of

skills and strength, who are the most gifted competitors and the just winners of the contest.

It is worth noting that Cicero introduced the term disputatio when he created the technical language of Roman

philosophy based on the Greek language. In Ciceros Tusculanae disputationes, the disputatio was a type example of

philosophical contest based on reasoning and developed upon the basis of the dialogic model of Greek philosophy. Thus,

for Cicero, the term disputatio referred to a philosophical contest as opposed to a physical one. A disputatio is a

confrontation, a mental certamen. Conversely, todays Italian use of the term disputare refers to the participation in

competitive sports matches or championships, that is to say, disputare refers to physical challenges. This shows that

although Cicero used the word certamen to translate the Greek word agn, he deliberately neglected the connection

between agn/certamen and the Greek sport culture. In Ciceros translation, the reality of agn is reduced as it is only

related to philosophical contests. This reduction of the term agn is due to the fact that Cicero was mirroring a

widespread attitude among Roman intellectuals of his time.

Page | 102

Research Publish Journals

ISSN 2348-3156 (Print)

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN 2348-3164 (online)

Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp: (101-105), Month: July - September 2015, Available at: www.researchpublish.com

In Ciceros time, Roman conservative intellectuals believed that the political decline of Greece was a consequence of the

agonistic and sportive element in Greek culture. For example, the poet Ennius regarded the exercises practiced in the gym

and athletes nakedness as examples of moral outrage and moral corruption. For Tacitus, the paideia based on gymnastics

and on agnes, resulted in a type of education that corrupted the youth. By engaging in sporting activities, young

members of society developed no interest in military service and became effeminate. Lastly, the philosopher Seneca

criticized coaches who trained young people for agnes on the grounds that physical exercise exhausted the mind and

made people unable to engage in more serious studies. The Christian contempt for sporting activities is likely to have its

roots in the Roman hostility towards Greek agones. In alignment with the Roman reduction of agn to philosophical

contests, Christians reduced the nature of agn to its dimension of suffering and pain. In fact, agona agony was the

only word remaining in the Middle Ages among those connected to the word agn.

Not everybody in Rome rejected the Greek agonistic spirit. Rather, some important Romans tried to introduce agnes in

their society. For example, Augustus loved Greek agnes so much that, after his victory at Actium in 31 BCE, he

organized athletic games, called actia, in Nicopolis. Other Roman emperors included sports competitions in their public

festival and games. Among those competitions introduced by Roman emperors, we find the so-called Neronia introduced

by Nero, the emperor who wanted to be a Greek philosopher, and the agn Capitolinus, celebrated every four years within

the festival of the City. Emperor Domitian introduced the agon Capitolinus, which soon was added to the other prestigious

games of the so-called periodos. Domitian found an official space for athletic competitions in Rome, the square. In fact,

the name of one of the most famous squares of Rome, Piazza Navona, which follows the shape of the stadium built by

Domitian in 86 a. C., comes from the expression square in agone.

However, despite the apparent spread of agnes in Rome, the figure of the athlete, who starred in Greek agnes, always

had a bad reputation among the Romans. The agnes were mostly considered performances in which the athlete was just a

performer-actor (or actress, because some authors tell of women who appeared in struggles and competitions fighting

against other women) and not an athlete in the strictest sense. Moreover, athletes were often criminals and thugs (or

prostitutes) who, during the day, could be seen competing in the stadium and in the evening were hired to carry out

killings in some slum of the city. In sum, the public image of the athlete did not contribute in the popularization and

implementation of Greek agnes in Rome.

So far, we have provided a historical background to understand how agn was generally conceived in Rome. In the

second part, we identify the constituent elements of the Roman certamen system in order to compare it to the Greek

agonistic system. To do so, we will draw on two recent books about the nature of agn: Heather Reids Philosophy and

athletics in the Ancient World: Context of Virtue and Yunus Tuncels Agon in Nietzsche.

III. GREEK AGN VERSUS ROMAN CERTAMEN. A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS

As we argue in the first section, our sporting tradition is an heir of Greek and Roman cultures. However, the two concepts

used to refer to sporting contests in Greek and Roman cultures express different meanings that are not comparable to each

other. To put it shortly, whereas the concept of certmamen has a strong and deep connection with military and warlike

contexts, the concept of agn has a communitarian and more pedagogical meaning, as expressed by its root * ag, from

which the Greek word agora square derives. By categorizing agn as communitarian and pedagogical, we mean that

the term agn refers to an activity in which citizens learn and embody the main skills, values, and principles of the

society they are part.

Roman sport activities were very similar to a circus, as professor Heather Reid argued. In this sense, certamen is a ludus,

that is, a spectacle in which actors-athletes act in physical performances and show their body and skills. Understood in

this way, certamen is more a game and a spectacle, and less a pedagogical activity. The spectacular nature of Roman

games contrasts with the pedagogical aspect of Greek agones. For Romans, agn was stupid because members of the

society were primarily soldiers and businessmen, and then citizens. Soldiers were forced to take long marches every day,

to use weapons and arms in fights and battles, and to fight in certamina, which were not a simulation of war but true

fights and battles in which the soldiers physical/sport skills allowed them to survive. This does not mean that certamina

were not sources of values for those who engaged in them. Rather, the values and principles expressed in Roman

certamina refer to the individual instead of to the community. Therefore, the main difference between agn and certamen

is that the latter is related to individualistic conceptual, political, educational, and aesthetic categories, while the former is

Page | 103

Research Publish Journals

ISSN 2348-3156 (Print)

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN 2348-3164 (online)

Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp: (101-105), Month: July - September 2015, Available at: www.researchpublish.com

linked to communitarian values and principles.

It might be true that the individualistic principles and values of certamen are in line with those that are the basis of,

nowadays, modern-liberal societies. However, communitarian values found in agn are more valuable from a pedagogical

standpoint. A clear example of this is that, whereas agn became a metaphor of dialogue and peaceful confrontation

among people to affirm their own virtues, values, and personal worth, certamen was intrinsically linked to violent

confrontation and war.

Despite being opposed to each other, agn and certamen blended when Greek culture and Roman culture merged in what

is called the Greco-Roman culture. In so doing, a constant tension between these two ancient ways to understand sports

arose. This is key to our debate because the constant tension between agn and certamen influences our contemporary

conception of sport, which is a result of the Greco-Roman culture. Contemporary sports, thus, are both certamen and

agn. This creates a constant tension between two opposing and ineliminable realities: that of the communitarian civic

education and that of the individualistic will to outperform the others and beat them in every possible field. The tension

between these two realities can be observed in every philosophical debate on sports, such as the debates on the

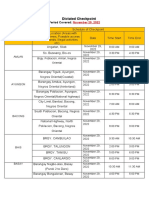

commodification of sports and on the technologization of sports. Table 1 shows some of the terms and concepts linked to

each of the two opposing dimensions of contemporary sports.

Table 1: comparison between agn and certamen

Sport as agn

1. communitarian

2. meeting

3. with

4. virtues

5. action

6. integration

7. spiritual

8. evaluation

9. honour

Same root

Action/performance evaluated in public;

Desire to achieve a goal and to show the

participants personal value and virtue;

Idea of discerning and deciding who is the

best competitor

Sport as certamen

1. individualistic

2. fight

3. versus

4. skills

5. performance

6.opposition

7. material

8. measure

9. money

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In the previous section, we argued that modern-day sports embody features of both certamen and agn. Sport is arguably

an agonal-certamen that embodies features of agn and of certamen, depending upon the context in which it is developed.

Agn and certamen represent two opposing and irreconcilable poles. The tension between the two opposing poles

generates the ethical and moral dynamics of sport and provides philosophers with opportunities for reflecting on sport and

its meanings.

From a pedagogical standpoint, it would be misleading to think that the agonal conception of sport is the right and most

appropriate view of sport and that the certaminal is the wrong view. From a philosophical standpoint, it is necessary to

embrace both realities of contemporary sports in order to build research tools to detect the role that the two different

conceptions of sport (agonal or certaminal) play, not only in the conception of sport by those practically engaged in

sports, but also in theoretical analyses of sports.

The reflection on the polarity agn-certamen is the point of departure to define the agonal pedagogy, which is a

theoretical and practical science of education that regards sport as a tool to help people - as individual subjects - show

their individual principles and values, which can be turned into social goods and social values useful to build better

societies and better communities. Social values and principles are transmitted through the individuals participation in

social practices. Likewise, social practices influence and shape some of the main values and principles of society. This is a

two-way relationship. This being so, society uses sport as a part of its educational system in order to educate and to

transmit values to new generations. The role of our pedagogical studies of sport is to learn how to shape sports in a way

that the values, norms, and rules transmitted through the practice of sports help people develop and improve themselves as

communities of peace and tolerance.

Page | 104

Research Publish Journals

ISSN 2348-3156 (Print)

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN 2348-3164 (online)

Vol. 3, Issue 3, pp: (101-105), Month: July - September 2015, Available at: www.researchpublish.com

What we have briefly presented here by analyzing the relationship between agn and certamen in Western sport culture is

just a starting point and a small scientific contribution that needs to be developed further through a deeper philosophical

study, as well as, through a practical pedagogical application.*

* Authors contribution. This study is the result of collaboration between the three authors. Their contribution can be

summed up as follows: Emanuele Isidori wrote abstract, chapter I and IV; Javier Lpez Fras wrote chapter II; Rafael

Ramos Echazarreta wrote chapter III.

REFERENCES

[1] Gadamer H.G., Truth and Method. New York: Continuum, 1975.

[2] Isidori E., Filosofia delleducazione sportiva. Roma: Editrice Nuova Cultura, 2012.

[3] Miller S.G., Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

[4] Reid H.L., Introduction to the Philosophy of Sport. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012.

[5] Weeber K.W., Panem et circenses: Massenunterhaltung als Politik im antiken Rom. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern,

1994.

Page | 105

Research Publish Journals

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Sea People-Theories of Their OriginDocument38 paginiSea People-Theories of Their OriginMaria Stancan100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Spaceships of Science FictionDocument116 paginiSpaceships of Science FictionBruce Lee100% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Preparing A Job ApplicationDocument17 paginiPreparing A Job Applications_abroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Won Park - Dollar Battle-Gami PDFDocument279 paginiWon Park - Dollar Battle-Gami PDFKeno Souza Gens100% (6)

- Character Formation Chapter 1Document15 paginiCharacter Formation Chapter 1Amber EbayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gadamer and The Truth of HermeneuticDocument12 paginiGadamer and The Truth of HermeneuticmajidheidariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gladius Vs SarissaDocument4 paginiGladius Vs Sarissatemplecloud1100% (1)

- JKJKDocument561 paginiJKJKRobert Luhut Martahi SianturiÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of The Afghans (1858) by J.P. FerrierDocument517 paginiHistory of The Afghans (1858) by J.P. FerrierBilal AfridiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nicholas Agar-The Sceptical Optimist - Why Technology Isn't The Answer To Everything-Oxford University Press (2015) PDFDocument222 paginiNicholas Agar-The Sceptical Optimist - Why Technology Isn't The Answer To Everything-Oxford University Press (2015) PDFJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brown 1980Document10 paginiBrown 1980Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- KINES 345 Group Project Normative Theories Sport DopingDocument4 paginiKINES 345 Group Project Normative Theories Sport DopingJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH02Document5 paginiCH02Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why ISIS Declared War On Soccer - Andrés MartinezDocument4 paginiWhy ISIS Declared War On Soccer - Andrés MartinezJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Post - 'We Are All On The Front Lines' - Canadian Reportedly Killed Fighting ISIL Wrote Essay About Why He Went To WarDocument5 paginiNational Post - 'We Are All On The Front Lines' - Canadian Reportedly Killed Fighting ISIL Wrote Essay About Why He Went To WarJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japan Lays Groundwork For Boom in Robot Carers - World News - The GuardianDocument3 paginiJapan Lays Groundwork For Boom in Robot Carers - World News - The GuardianJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oxford Debates - Doping - June '09Document12 paginiOxford Debates - Doping - June '09Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phil SportDocument110 paginiPhil SportJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gallagher 3Document11 paginiGallagher 3Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hermeneutics SportDocument8 paginiHermeneutics SportJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- "After Doping, What?: The Morality of The Genetic Engineering of Athletes" StrategyDocument5 pagini"After Doping, What?: The Morality of The Genetic Engineering of Athletes" StrategyJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sport Philosophy Eastern Philosophy and Pragmatism - AEDocument22 paginiSport Philosophy Eastern Philosophy and Pragmatism - AEJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCSSR 2014 0019Document9 paginiPCSSR 2014 0019Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philostratus' Gymnasticus Reveals Ancient Athletics' Deeper MeaningDocument13 paginiPhilostratus' Gymnasticus Reveals Ancient Athletics' Deeper MeaningJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Pa Style 2010Document62 paginiA Pa Style 2010Ana Margarida FerrazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ac AC Advanced Olympic Research Grant Programme 14 15Document7 paginiAc AC Advanced Olympic Research Grant Programme 14 15Javi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophical Dimensions SportDocument4 paginiPhilosophical Dimensions SportJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neurosc Psich SportDocument24 paginiNeurosc Psich SportJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reseña. SavulescuDocument9 paginiReseña. SavulescuJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- "After Doping, What?: The Morality of The Genetic Engineering of Athletes" StrategyDocument5 pagini"After Doping, What?: The Morality of The Genetic Engineering of Athletes" StrategyJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Socrates CosmopolitismDocument17 paginiSocrates CosmopolitismJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gadamer and Philosophical Ethics. KennyDocument20 paginiGadamer and Philosophical Ethics. KennyJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge Plato AristotleDocument16 paginiKnowledge Plato AristotleJavi LoFriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- TinkDocument2 paginiTinkenulamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zulfikar Ali BhuttoDocument105 paginiZulfikar Ali BhuttoSK Md Kamrul HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manila's History from Prehistoric Settlement to Post-WWII RebuildingDocument1 paginăManila's History from Prehistoric Settlement to Post-WWII Rebuildingzurc ughieÎncă nu există evaluări

- FirstSixBooksofCsarsCommentariesontheGallicWar 10132766Document241 paginiFirstSixBooksofCsarsCommentariesontheGallicWar 10132766oliver abramsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Download Test Bank For Conceptual Physical Science 4th Edition Hewitt PDF Full ChapterDocument36 paginiFull Download Test Bank For Conceptual Physical Science 4th Edition Hewitt PDF Full Chapterzacharyjackson20051996pbd100% (15)

- Reinforcement Activity No. 7 RPHDocument2 paginiReinforcement Activity No. 7 RPHfayeiyanna29Încă nu există evaluări

- Ulrich BeckDocument6 paginiUlrich Beckyizheng75% (4)

- The Great WarDocument4 paginiThe Great WarMargarita ArnoldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Feminist Security StudiesDocument4 paginiIntroduction To Feminist Security Studiesraymond gwapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP US History - Timeline - The PresidentsDocument7 paginiAP US History - Timeline - The PresidentsAeronautix100% (1)

- House SectionDocument1 paginăHouse SectionRahul TiwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dictated Checkpoint Schedule 11-29-2022-EDocument6 paginiDictated Checkpoint Schedule 11-29-2022-EGuihulngan PulisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presidential DoctrinesDocument15 paginiPresidential DoctrinesNina_Stefanovi_7234Încă nu există evaluări

- Dixon Joe - IsKF Karate-Do in BCDocument200 paginiDixon Joe - IsKF Karate-Do in BCReda Youssef100% (1)

- The New York Times Current History: The European War, February, 1915 by VariousDocument225 paginiThe New York Times Current History: The European War, February, 1915 by VariousGutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wintershall DeaDocument11 paginiWintershall Dearadoslav micicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 14 Winston Churchill 10.23Document155 paginiLesson 14 Winston Churchill 10.23zhoubojia2014Încă nu există evaluări

- Cold War Flashcards - UpdatedDocument20 paginiCold War Flashcards - UpdatedZackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weil Family - MacTutor HistoryDocument4 paginiWeil Family - MacTutor Historyjohn_k7408Încă nu există evaluări

- History Form Two-Topic 1Document6 paginiHistory Form Two-Topic 1edwinmasaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lady or The Tiger Study Guide PDFDocument8 paginiThe Lady or The Tiger Study Guide PDFA. A. Suleiman100% (1)

- Philippines: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument27 paginiPhilippines: Republic of The PhilippinesAcad CARTCÎncă nu există evaluări

- World of Trolls - T&T With Just One Die - Vin's T&T TrollBridgeDocument2 paginiWorld of Trolls - T&T With Just One Die - Vin's T&T TrollBridgeSean MclarenÎncă nu există evaluări