Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Managerial Commitment Impacts Safety Behavior

Încărcat de

Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Managerial Commitment Impacts Safety Behavior

Încărcat de

Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

7th

American Society of Safety Engineers

Middle East Chapter

Professional Development Conference & Exhibition

Kingdom of Bahrain, March 18-22, 2006

ASSE- 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

Prof. Dominic Cooper* C. Psychol. C.FIOSH, BSMS Inc. 6648 East State Road 44, Franklin, Indiana, 46131, USA.

ABSTRACT

Behavioral safety was implemented in a nickel refinery

over a 93-week period with 275 employees, plus

contractors. Measurement focused on managerial

commitment behaviors and employee safety behaviors.

Safety behavior improved by 40%. Lost time injuries

reduced by 82.2% in the first year, reducing to Zero in the

second. Minor injuries reduced by 35%. Multiple regression

showed managerial commitment impacted 35% on

employee safety behavior. The timing and magnitude of

impact suggests management must continually demonstrate

their commitment to safety.

KEYWORDS

Managerial Commitment, Safety behavior, Goal-setting,

Feedback.

1.

INTRODUCTION

Top performing companies express high commitment to

safety by developing a process in which the workforce can

participate, and which can be implemented and monitored

so both management and the workforce can receive

feedback1. A systematic behavioral safety process fulfils

these conditions. The intention is to focus workers attention

and action on their safety behavior to avoid injury.

Interventions are aimed entirely upon the observable

interactions between safety behavior and the working

environment.

Behavioral safety attempts to identify those unsafe

behaviors implicated in the majority of injuries. These

behaviors and/or their proxies (e.g., hoses left lying across

walkways) are developed into specific behavioral

checklists. Trained observers use these to monitor and

record peoples work behavior on a regular basis (e.g.,

daily). Derived from the observation results, Percent safe

scores provide feedback so people can track their progress

against self-set, assigned or participative improvement

goals2. Feedback mechanisms include verbal feedback at

the point of observation, graphical charts and/or written

performance summaries so corrective actions can be

taken3,4. Results indicate significant reductions in injury

rates are possible within a relatively short time5 with the

impact lasting for many years6.

Those companies implementing behavioral safety possess a

high degree of organizational commitment to safety7.

However, the commitment of individual managers to the

organizations safety goals and the behavioral safety

process is a significant factor8. Managers need to provide

the necessary resources, give the workforce the authority to

run and manage the process alongside the usual safety

management systems, and actively support the process. In

many instances this does not occur.

2.

MANAGEMENTS COMMITMENT

Managerial commitment is defined as "engaging in and

maintaining behaviors that help others achieve a goal8.

Broadly speaking, measurement can be undertaken in two

ways: Direct questions are asked of managers9 or their

commitment behaviors are monitored10. Not many

managers admit they are uncommitted to safety when

asked, whereas behavior provides the ultimate proof of

commitment10. An extensive search of the psychological,

managerial and safety literatures reveals the existing

managerial commitment evidence is almost entirely based

on perceptual questionnaires or semi-structured interviews.

With few exceptions8,11,12 little empirical work has assessed

the actual impact of managerial commitment behaviors on

employee behavior.

Management Levels: Although unclear, the available

evidence suggests different management levels exert

different effects on employee behavior. For example, in a

Dutch questionnaire study of 207 workers on 15

construction sites13, it was found that senior managers exert

a greater influence on employee motivation to behave

safely than supervisors do. Conversely, a Canadian

* Prof. Dominic Cooper BSMS Inc. 6648 East State Road 44, Franklin, Indiana, 46131, USA Tel: +1 (317) 736 8980

E-mail: dom@bsms-inc.com

ASSE 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

study14,15 using a questionnaire survey with 23,615

production workers, suggest supervisors exert a greater

influence on employee behavior than senior plant managers

do. These two examples suggest the effects of

managements commitment are likely to be moderated by

situational aspects such as the prevailing safety culture16,

industrial sector and type of organizational structure17.

3.

categories (e.g., housekeeping, personal protective

equipment, etc.) to facilitate analyses and feedback.

Each checklist contained three columns: Safe; Unsafe, and

Unseen. The safe and unsafe columns were used to

calculate an Observed Percent Safe score, which was used

as the primary dependent variable in this study. The unseen

column was used when behavior did not take place during

an observation session (i.e. it could not be observed).

STUDY AIMS

The purpose of the current study was to ascertain the impact

that managerial support behaviors exerted on employees

safety behavior, utilizing senior, middle and front-line

management behavioral checklists over a 93-week period in

a Nickel Refinery.

4.

METHOD

Participants and Setting: The refinery contained eight main

departments on a 55-acre site, employing approximately

275 personnel. The five main production departments

operated a continuous 24-hour, 3 x 8 hour rotating shift

system, with two shifts 'resting' at any one time. Shipping

operations worked a 2 x 8 hour shift system (am and pm).

Site support functions comprised administration,

laboratories, medical facilities, engineering maintenance,

and safety, who worked a 'normal' five-day, 39-hour week.

Transitional contractors from seven companies also

participated (e.g., welders, fitters, canteen staff, cleaners,

etc.).

Intervention Design: This study utilized a repeatedmeasures time series design with 43 work groups across

three separate interventions, over 93 weeks. Intervention 1

lasted 29 weeks, with 31 and 33-week durations for

interventions 2 and 3, respectively (see Figure 1). The

primary measurement variables focused on employee safety

behavior and managerial supportive behavior. Injury rates

and their associated costs comprised the secondary variable

used to assess the efficacy of the interventions.

Figure 1: Experimental Design

Intervention 1

(n=29 weeks)

Baseline

(A)

Intervention

(B)

Intervention 2

(n=31 weeks)

Baseline

(A)

Intervention

(B)

Intervention 3

(n=33 weeks)

Baseline

(A)

Intervention

(B)

Management's

Commitment:

Managers

themselves

identified the management commitment behaviors. The

resulting behavioral support checklists did not change

throughout the duration of the study. Senior managements

checklist contained 11 items (See Figure 2 for an example),

and middle managements contained 16 items. The

managers were trusted to complete these once per week on

a self-report basis. A visible ongoing support (VOS) proxy

measure provided an indicator of front-line managements

commitment. Completed by employee observers weekly,

these contained seven items. Each contained two columns

(Yes & No), so an Observed Percent Support score could

be calculated.

Figure 2: Senior Management Commitment Index

1 Accompanied an observer during an observation

2 Attended a workgroup feedback meeting

3 Discussed safety performance with employee(s)

(one-to-one)

4 Discussed line management on-going support

5 Developed plans for corrective actions

6 Ensured that some corrective actions were closed

7 Approved funding for safety improvement(s)

8 Reviewed progress with management team and/or

SHE advisor

9 Conducted an incident investigation (as required)

10 Attended a safety training course

11 Conducted safety related training

Injuries: The lost-time injury (LTI) and minor injury rate

(inclusive of occupational health exposures) were the

companys primary outcome measures used to assess the

effectiveness of the behavioral safety process. The site

calculated these based on the number of incidents per

200,000 hrs worked.

5.

Safety Performance Measures: The site was divided into 27

observation areas across eight main departments, containing

43 work-groups. Based on analyses of the companys

historical injury records for the previous two years,

behavioral checklists for the 27 areas were developed. Each

contained a maximum of 20 behaviors (e.g., personnel are

holding the handrails when using stairs) pertaining to the

work area of interest. These were placed into various

PROCEDURE

Obtaining Employee Participation: Briefings with all site

personnel took place prior to any training or

implementation taking place (inclusive of contractors), to

seek employee participation. At these, the workforce

indicated their most serious safety concerns and the most

common unsafe behaviors they engaged in. Actions on the

concerns were completed soon after the briefing sessions

and then publicized to reinforce employee participation.

ASSE 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

The unsafe behaviors were used to help develop behavioral

checklists.

Project Team and Managerial Training: A project team

comprising two hourly paid coordinators (one for direct

employees and one for external contractors) and a safety

champion drawn from the senior management team on site

were trained over five days in the principles and practice of

behavioral safety.

All managers also attended a one-day training session (n=5)

to acquaint them with the projects logistics, to develop the

management support checklists, and be trained in

behavioral observations.

Observer Recruitment & Training: The project team

initially recruited and trained 113 volunteer observers. Each

were trained how to observe, give verbal feedback, set

participative improvement goals and conduct weekly

feedback sessions with their workgroups. A one-week

practice period (or shift cycle) facilitated accuracy checks

on the observations.

Establishing Baselines: To establish a baseline, observers

monitored everyone in their workgroup for 15-30 minutes

every day they were at work, for four weeks (or four shift

cycles). Observers randomly chose the time of day when

their observation would take place. To minimize the

potential impact on baseline performance, observers were

instructed not to give verbal feedback unless someone was

in imminent danger of hurting themselves or their

colleagues. Written or posted graphical feedback was not

provided. Observations were recorded and analyzed in a

dedicated

computerized

behavioral

safety-tracking

program.

Goal-setting: At the end of each four-week baseline period,

workgroups attended their respective goal-setting session

led by the workgroup observers, where participative goals

were set5. Each workgroups goal was posted on their

graphical feedback chart as a line at the appropriate

percent-safe goal level. No explicit goals were set for the

managerial support behaviors.

Monitoring & Feedback: After goal setting, observers

continued to monitor their colleagues safety behavior on a

daily basis for 15-30 minutes at randomly chosen times of

day. The project co-coordinators entered the observation

data at the end of each working day into the tracking

program. The managers entered their own checklist scores

directly into the online computer program once per week.

Observers completed VOS checklists weekly to indicate

whether they had received the requisite support from frontline managers.

Each workgroups observation data were analyzed weekly to

provide the percent safe score, which was posted on their

graphical feedback chart. A written analysis reporting

results by category of behavior (e.g., use of tools,

housekeeping, etc) was discussed at weekly 30-minute

meetings. Monthly reports that summarized the sites

average percent safe score, the percentage of observations

missed and the average percent support score for each

managerial level were also produced for senior

management meetings.

Repeat Interventions: Excluding the initial workforce

briefings and project team training, Interventions 2 and 3

repeated the above process in exactly the same way.

Different workers observed during each intervention: The

intention was for all workgroup members to become an

observer eventually. Each intervention used slightly

different behavioral checklists, developed on an

evolutionary basis. Behaviors consistently recorded as

100% safe for an extended period during the previous

intervention were replaced. Each checklist was approved by

the appropriate workgroup prior to being put to use.

6.

RESULTS

Behavioral Safety Performance: For Intervention 1(see

Table 1) the average four-week baseline score (56.5%;

S.D.= 6.14) for the site as a whole indicated that just over

half of the behaviors observed were performed safely when

the project began. The sites average safety goal of 79

percent represented a goal-difficulty level of 22.5 percent

improvement. The mean average percent safe score of

82.16 (SD=7.30) shows the site goal was exceeded. A Oneway Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) reveals the change in

safety performance scores was highly significant [F (1, 27)

= 44.09, p<001]. Shown in Figure 3, the site goal was

achieved within seven weeks of setting the goal, with this

level of performance maintained or exceeded over the

remaining 18 weeks of the intervention.

Within Intervention 2, the average baseline score of 67.75%

(SD=3.50) for the site indicate underlying safety behavior

had improved by some 11.25% over Intervention 1

baseline. The average site goal was 83 percent. The mean

average percent safe score of 83.15%, (S.D.=5.65) shows

the average site goal was achieved at Week 12 and more or

less maintained or exceeded for the next 14 weeks. A Oneway Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) again reveals the

change in safety performance scores from the baseline

average was highly significant [F (1, 29) = 27.66, p<001].

Intervention 3 results show the site's baseline score of

81.5%, (SD=1.92) indicated a further underlying 13.75%

improvement in safe behavior compared to the Intervention

2 baseline. The site's average 93% safety improvement goal

represented a further 10% improvement over Intervention 2.

Intervention 3 goal was attained at Week 9 but was not

maintained until Week 13 for the remaining 16 weeks. The

overall mean average percent safe score of 92.83%

ASSE 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

(SD=4.44) indicates the site achieved its goal of a 93

percent average site goal for this intervention. Again, this

represents a highly significant change [F (1, 29) =24.83,

p<001] from the Intervention 3 baseline.

Table1: Individual Phase Mean Average Percent Safe Scores

Period

% Safe B/Line

Mean

S.D.

Ave

% Safe

Goal

Intervention 1 (n=29 Wks)

56.50

6.14

79

82.16

7.30

22.5

Intervention 2 (n=31 Wks)

67.75

3.50

83

83.15

5.65

15.25

Intervention 3 (n=33 Wks)

81.50

1.92

93

92.83

4.44

13.75

Figure 3: Average weekly Site % Safe Scores for each

intervention

% Safe Performance

Mean Ave

S.D.

Goal Difficulty

Level %

in 2003 to 19.74 providing a total reduction of 63% over

three years (see Figure 5) as the site continued with the

behavioral safety process.

Figure 4: Number of lost time accidents and injury rates

by year

100

# of Lost Time Injuries

Incident Rate per 200,00 hrs

Goal

3.5

90

Goal

80

# of Lost Time

Injuries

Goal

Baseline

% Safe

70

Start of First

Intervention

Incident Rate per

200,00 hrs

2.5

5

2

4

Baseline

60

1.5

3

50

Intervention 1

Intervention 2

Intervention 3

Baseline

40

1

13

17

21 25

29 33

37

41

45

49

Weeks

53

57

61

65

69

73

77

81

85

89

93

0.5

1

0

0

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

Year

Injury Reduction: In terms of corresponding injury

performance during the 93-week study period, the lost-time

injury rate (# of injuries/per 200,000 hrs worked) for 2001

was 0.45 compared to 2.54 in the year 2000, representing

an 82.2% decrease. As shown in Figure 4, by the end of the

study period in 2002, the lost-time injury rate had reduced

to zero. This remained zero in 2003 (The project continued

unaided during this time).

In terms of minor incidents (inclusive of occupation health

exposures to nickel particulates and minor physical injuries)

to both direct employed and contractors, the minor incident

rate in 2000 was 54.05.

Figure 5: Number of Minor Injuries and Injury Rates

(inc. of Occ. Health Exposures)

# of Recordable Injuries

Recordable Incident Rat e Per 200,00 0 hrs Worked

120

100

# of

Recordable 80

Injuries

60

54.05

44.65

35.25

40

19.74

20

This reduced to 44.65 in 2001 and 35.25 in 2002. Thus

minor incidents reduced by approximately 35% over the 93week period. The minor incident rate continued to decrease

0

2000

2001

2002

Ye ar

2003

Managements Commitment: The main aim of this study

was [a] to explore the potential impact of management

support on safety performance and [b] ascertain if the

impact of management support differs by managerial level.

Multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), correlational

analysis and multiple regressions were used to assess the

relationship between the different levels of management

support and safety performance.

Time Series Data Transformation: To avoid spurious

correlations or multi-collinearity when using regression

methods, time series analysis requires stationarity be

established through differencing or some other technique to

ensure the ranges of the different series are invariant18.

Differencing is a data pre-processing step which attempts to

de-trend data to control autocorrelation and achieve

stationarity by subtracting the previous series value from

the current value. Single differencing was used for each

data series. To check if each data point was independent of

others in a series (i.e., random), each was analyzed via

autocorrelations using natural logs to remove any nonconstant variance. No significant autocorrelations were

obtained, indicating that each separate data series contained

random or independent data.

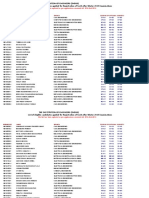

Descriptive Statistics: The average percent support scores

for all three management levels, across all three

interventions are presented in Table 2. These show that both

middle management and VOS levels remained fairly static,

whereas those for senior management steadily increased,

suggesting an interaction between management support and

intervention period.

Table 2: Individual Phase Mean Averages for

Leadership and Support Behaviors

Interactions: Multivariate analysis tested for possible

interactions. Management commitment (Senior, Middle

Management and VOS) was entered as the dependent

variable with Intervention period treated as the fixed factor.

Percent safe scores were entered as the covariate. The

results (see figure 6) show there was a commitment x

intervention interaction, that was greater for VOS [F (3, 89)

= 19.24, p<.01], followed by senior [F (3, 89) = 14.93,

p<.01] and middle management commitment [F (3, 89) =

9.93, p<.01]. Moreover, the magnitude of support differed

significantly [F (2, 89) = 151.63, p<.01] between the three

managerial levels across the three interventions.

Figure 6: Interactions between management support

and intervention

75

70

65

60

55

50

VOS

Middle Management

Senior Management

45

Period

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

Percent Managerial Support Scores

ASSE 0307-013

SML

Mean S.D.

MML

Mean S.D.

VOS

Mean S.D.

Intervention

1 (n=29

Wks)

64.12

58.47

55.30

Intervention

2 (n=31

Wks)

71.23

8.52

58.53

2.52

50.65

3.31

Intervention

3 (n=33

Wks)

75.53

7.76

59.15

4.23

57.30

1.57

Totals

(n=93 Wks)

70.54

9.72

58.73

3.11

54.46

4.51

9.57

2.03

Intervention

5.11

SML = Senior Management; MML = Middle Management; VOS = Visible Ongoing Support

Correlation analyses: Pearson product-moment correlations

(r) established the degree of association between each

management support variable and the percent safe score for

the whole study period and for each separate intervention.

As there were no specific hypotheses about the direction of

the relationships, two-tailed tests for all correlations were

used (see table 3).

ASSE 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

Table 3: Inter - variable correlation's for study period

Whole Study period(n=93 Weeks)

SML

MML

VOS

SML

1

0.32**

0.042

MML

1

0.091

VOS

1

Intervention One (n=29 Weeks)

SML

1

0.215

-0.074

MML

1

-0.017

VOS

1

Intervention Two (n=31Weeks)

SML

1

0.13

0.05

MML

1

0.05

VOS

1

Intervention Three (n=33Weeks)

SML

1

0.55**

0.01

MML

1

0.25

VOS

1

% Safe

0.516**

0.456**

0.204*

0.70**

0.58**

-0.23

-0.57**

0.32*

0.53**

0.78**

075**

-0.06

*=p<.05; **=p<.01 ; SML = Senior Management; MML = Middle

Management; VOS = Visible Ongoing Support

Whole Study Period: Across the whole study period,

significant correlations were obtained for senior (r=0.52,

p<. 01, n=93) & middle (r=0.46, p<.01, n=93) management

scores and Visible Ongoing Support (r=0.20, p<.05) with

2

percent safe. The coefficients of determination (r ) for

senior (0.27) & middle (0.21) management and VOS (0.04)

scores indicate a direct link between different levels of

managerial support behavior and employee safety behavior.

Intervention Periods: Correlational analyses by intervention

indicate that each level of managerial support is related to

safety behavior at different moments in time. Senior

management scores were positively related to safety

behavior during interventions 1 (r=0.70, p<.01) and 3

(r=0.78, p<.01), but negatively related during Intervention 2

(r=-0.57, p<.001). Significant relationships were also

obtained for middle management during Interventions one

(r=0.58, p<.01), two (r=0.32, p<.05) and three (r=0.75,

p<.01). A significant relationship for VOS was obtained

only during Intervention 2 (r=0.53, p<.01). Thus, there

appears to be a robust, but dynamic, relationship between

the three levels of management support and employee

safety performance.

Inter-Variable Correlations: Inter-variable correlational

analyses yielded a significant correlation between middle

and senior management scores (r=0.32, p<0.01, n=93)

across the whole study period. An exploration of these

correlations for each intervention shows that middle

management support was significantly related to senior

management support (r=0.55, p<.01, n=31) during

Intervention 3 only. No other significant inter-variable

correlations were obtained.

Regression Analysis. To attempt to tease out more specific

relationships, stepwise multiple correlational techniques

were used to identify the magnitude of variance explained

by each variable for the whole study period. Observed

percent safe was the dependent variable with senior

management, middle management and Visible Ongoing

Support treated as independent variables. Shown in Table 4,

2

the adjusted R results indicate combined senior and middle

management support significantly [F (2, 92) = 25.27,

2

p<.01] impacted safety performance (R = 0.35) by about

35%. Visible Ongoing Support (VOS) appears to have had

no impact on the percent safe data over the whole study

period.

7.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here demonstrate the effectiveness of

behavioral safety in the workplace19, particularly when

implemented by employees5. Average behavioral safety

performance for the site increased substantially over each

separate intervention, achieving an overall 36%

improvement. Correspondingly, the site also achieved a

100% reduction in the lost-time injury rate and 35% in

minor incident rate, suggesting a 1:1 ratio between safety

behavior improvement and minor incident reduction.

Management's Commitment: This study provides

compelling evidence regarding the impact that management

support behaviors exert on employee safety behavior, with

associated effects on injury rates. This supports findings11

that increasing the frequency of management subordinate

safety interactions positively influences safety performance.

Nonetheless, the magnitude of impact on employee

behavior for each separate level of management differed

across time, ranging from small to large effects20.

Different combinations of managerial levels exerted an

increasingly cumulative effect on performance. This

implies the influence of management commitment is

dynamic. It appears it takes time for a particular level of

managerial support to exert its influence, with the strength of

influence also varying. In practical terms, this suggests all

managerial levels must continuously demonstrate their

commitment to an improvement initiative from the

beginning, as it is unclear when this will actually exert its

intended influence and to what degree.

Explanations for the varying degrees of influence may

reside [a] in the design of the improvement process21 and

[b] in the effects of competing goals2. With regard to

design, the improvement process was owned and run by

the workforce themselves with management providing the

resources and fulfilling the roles of facilitators and problemsolvers. All members of a workgroup, inclusive of frontline management, were involved in decision-making

processes in terms of the behaviors to measure and the

ASSE 0307-013

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

improvement goal set. Each workgroup also obtained

regular process and outcome feedback about their progress,

with a substantial number of employees receiving

immediate verbal feedback during an observation. In

addition, many of the remedial actions reported were

completed by the workgroups themselves (albeit that

management provided the resources). Such design attributes

may account for improvements in employee behavior

independently of managements supportive behavior17. As

such, it is conceivable that when employee involvement is

low, management commitment effects are even greater.

With regard to competing goals, although senior

management support increased across the three

interventions, middle and front-line management scores

consistently remained within a 50-60% band. Middle and

front-line management were responsible for simultaneously

achieving multiple goals. These included productivity (i.e.,

quality, quantity and efficiency), safety, health and

environment,

employee

welfare

and

completing

administrative requirements, in addition to supporting the

improvement initiative.

The pursuit of multiple goals often involves trade-offs so

that one is attained at the expense of another2, or the

minimum amount of effort is expended so that all goals are

satisficed (i.e., met, but at lower levels of performance

that might have been achieved if successfully prioritized).

Of course, those goals leading to organizational rewards22

such as career progression are more likely to be vigorously

pursued. In this study, it would appear that satisficing or

in many cases simply not providing support became the

norm. This was further compounded during the study by a

lack of accountability for non-supportive behavior. A poststudy review addressed these issues by aligning managerial

accountabilities for the improvement initiative with the

system requirements of OSHAS 18001 (the site was

accredited in 2004).

Relationships between Management Levels: The managerial

paths of influence on employee behavior, is a significant

factor not yet fully explored23. It has been hypothesized

there is a linear relationship between hierarchical

management levels, in that senior managers influence the

behaviors of middle managers, who in turn influence the

behaviors of front-line managers, who subsequently

influence employee behavior23,11,12. The results reported

here indicate this is not always the case. The pattern and

magnitude of regression coefficients revealed greater

effects on employee behavior for senior management

support during all three interventions. Thus, senior

managements commitment directly influenced employee

behavior, independently of middle and front-line

management.

These results tend to support Andriessens13 conclusion that

higher level management have a greater degree of influence

on workers behavior than supervisors. Conversely, the

senior and middle management relationship obtained during

Intervention 3 also support the position of Simard and

Marchand14,15. They concluded higher level management

play a secondary role through their influence on lower

management levels. In this study, it appears senior

management commitment played both a primary and

secondary role that directly influenced both employee and

lower management behaviors. This potentially reconciles

the two opposing positions although further research is

required. However, organization structure may be a

moderating factor17. For example, in this study, middle

management had a very high degree of autonomy to meet

operational targets. Similarly, although they were not selfdirected work teams per se, the workgroups were also

highly autonomous. Therefore, middle managers or

employees were not dependent upon continual higher

management oversight.

8.

SUMMARY

Employee-led behavioral safety processes can help to

significantly reduce organizational injury rates within a

relatively short time frame. However, management need to

visibly demonstrate their support on a continual basis, as it

is unclear when and to what degree this will exert its

intended influence on performance. Regular measurement

of managerial commitment with a behavioral checklist

offers several distinct advantages. First, employees can see

that management is genuine in their desire to support safety

efforts, which will increase their motivation to improve.

Second, managers can set goals to increase the levels of

commitment displayed and provide themselves with the

feedback required to improve performance. Third, the

commitment data could be used as part of an annual

performance appraisal system to increase managerial

accountability for safety.

Each management level exerted independent and

cumulative effects on employee safety behavior. Senior

management commitment played a primary role in shaping

employee behaviors and a secondary role by shaping lower

management behavior that in turn impacted on employee

behavior.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

Gaertner, G., Newman, P., Perry, M., Fisher, G., &

Whitehead, K. (1987). Determining the effects of

management practices on coal miners' safety. Human

engineering and human resource management in

mining proceedings, 82-94.

Locke, E.A., & Latham, G.P. (1990). A theory of goalsetting and task performance. London: Prentice-Hall.

Algera, J.A. (1990). Feedback systems in

organizations. In: C.L. Cooper & I.T. Robertson(Eds)

ASSE 0307-013

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

The Impact of Managements Commitment on Employee Behavior: A Field Study

International review of industrial and organizational

psychology 1990. Vol 5,169-193. Chichester: John.

Wiley and Sons,

McAfee, R.B., & Winn, A.R. (1989). The use of

incentives/feedback to enhance work place safety: A

critique of the literature. Journal of Safety Research,

20, 7-19.

Cooper, M.D., Phillips, R.A., Sutherland, V.J & Makin,

P.J. (1994). Reducing accidents with goal-setting and

feedback: a field study'. Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 67, 219-240

Fox, D.K., Hopkins, B. L., & Anger, W.K. (1987). The

long-term effects of a token economy on safety

performance in open-pit mining. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analyses, 20, 215-224.

Gaertner, G., Newman, P., Perry, M., Fisher, G., &

Whitehead, K. (1987). Determining the effects of

management practices on coal miners' safety. Human

engineering and human resource management in

mining proceedings, 82-94.

Cooper, M.D. (2005). Exploratory analyses of

managerial commitment and feedback consequences on

behavioral

safety

maintenance.

Journal

of

Organizational Behavior Management.

Hollenbeck, J.R., Klein, H.J., O'Leary, A.M., &

Wright, P.M. (1989). Investigation of the construct

validity of a self-report measure of goal commitment.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 951-956.

Salancik, G.R. (1977). Commitment and the control of

organizational behavior and belief. In:B.M. Staw, &

G.R. Salancik (Eds.) Newdirections in organizational

behavior. Chicago: St Clair Press.

Zohar, D. (2000). A group-level model of safety

climate: Testing the effect of group climate on microaccidents in manufacturing jobs. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 85(4), 487-596.

Zohar, D., & Luria, G., (2003). The use of supervisory

practices as leverage to improve safety behavior: a

Research, 34 (5), 567577.

Andriessen, J. H. T. H. (1978). Safe behavior and

safety motivation. Journal of Occupational Accidents,

1, 363-376.

Simard, M., & Marchand, A. (1995). A multilevel

analysis of organizational factors related to the taking

of safety initiatives by work groups. Safety Science, 21,

113-129.

Simard, M., & Marchand, A. (1997). Workgroups'

propensity to comply with safety rules: The influence

of micro-macro organizational factors. Ergonomics,

40(2), 127-188.

Cooper, M.D. (2000). Towards a model of safety culture.

Safety Science, 32 (6), 111-136.

Roy, M. (2003). Self-directed work teams and safety:

A winning combination? Safety Science, 41, 359-376.

Von Eye, A., & Schuster, C. (1998). Regression

Analysis for Social Sciences. Academic Press. San Diego.

19. Grindle, A.C., Dickinson, A.M., & Boettcher, W. (2000).

Behavioral safety research in manufacturing settings: A

review of the literature. Journal of Organizational

Behavior Management, 20(1), 29-68.

20. Rodgers, R., & Hunter, J.E. (1991). Impact of

management by objectives on

organizational

productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 322336.

21. Cohen, H., & Cleveland, R. (1983). Safety program

practices in record-holding plants. Professional Safety

(March), 26-33.

22. Deming W.E. (1986). Out of Crisis. Boston:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

23. ODea, A, & Flin, R. (2003). The role of managerial

support in determining workplace safety outcomes.

Contract Research Report 044/2003. Sudbury: HSE

Books.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- ASSE Safety Conference ImpactDocument8 paginiASSE Safety Conference ImpactkusumawardatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Paper - 13419213 - 13419211 - 13419237Document3 paginiTugas Paper - 13419213 - 13419211 - 13419237Alimatun UlumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Supervisory Safety Leadership Behaviours in The Offshore Oil IndustryDocument14 paginiEffective Supervisory Safety Leadership Behaviours in The Offshore Oil IndustrymashanghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behaviouralsafetyf PDFDocument14 paginiBehaviouralsafetyf PDFAntony JebarajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Safety Perceptions Survey ResultsDocument31 paginiEmployee Safety Perceptions Survey ResultsardhianhkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety behaviour study in glove production companyDocument9 paginiSafety behaviour study in glove production companyAdel AdielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 271 - 279 HassanDocument9 pagini271 - 279 HassanTingting HowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploration of The Impact of Organisational Context On A Workplace Safety and Health InterventionDocument20 paginiExploration of The Impact of Organisational Context On A Workplace Safety and Health InterventionHasnainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Precautions AND Work EfficiencyDocument62 paginiSafety Precautions AND Work EfficiencyBrigette Kim LumawasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Assignment 2Document9 paginiQuestion Assignment 2Moiz AntariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior Based SafetyDocument13 paginiBehavior Based Safetyjahazi2Încă nu există evaluări

- Safety Leadership and Occupational Health and Safety Management SystemsDocument27 paginiSafety Leadership and Occupational Health and Safety Management SystemsAbdur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Workplace Safety Depends On Behavior Change Topics For Behavioral Safety ResearchDocument10 paginiWhen Workplace Safety Depends On Behavior Change Topics For Behavioral Safety ResearchNuzuliana EnuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zohar LuriaDocument31 paginiZohar Luriaconstantinop.gonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation & Training - HSE Behavior Based SafetyDocument26 paginiPresentation & Training - HSE Behavior Based SafetyHimawan Sutardjo100% (6)

- Safety Management: Philosophy and ApproachDocument13 paginiSafety Management: Philosophy and ApproachAdvocate K. M. Khairul Hasan ArifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Manual Behavior Based Safety ProgramDocument10 paginiSafety Manual Behavior Based Safety ProgramVictor TasieÎncă nu există evaluări

- M.E-ISE-2022-24-SM-Introduction To Safety Management-Folder No.1Document7 paginiM.E-ISE-2022-24-SM-Introduction To Safety Management-Folder No.1Veeramuthu SundararajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leading Safely: ISM PrinciplesDocument29 paginiLeading Safely: ISM PrinciplesmzuljeÎncă nu există evaluări

- EHS Topics ExpandedDocument10 paginiEHS Topics ExpandedAshwanth BhuvanrajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steps For The Behavioural Based Safety: A Case Study ApproachDocument4 paginiSteps For The Behavioural Based Safety: A Case Study ApproachPedro RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior Based Safety Approach To Advance Injury Free CultureDocument7 paginiBehavior Based Safety Approach To Advance Injury Free CultureRibka FridayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Involvement in Health and Safety: Some Examples of Good PracticeDocument33 paginiEmployee Involvement in Health and Safety: Some Examples of Good PracticejazÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 Elements of A Successful Safety & Health ProgramDocument3 pagini14 Elements of A Successful Safety & Health ProgramManus Agere100% (1)

- MAN MICDocument10 paginiMAN MICShrikant RathodÎncă nu există evaluări

- F2Blair 0810Document6 paginiF2Blair 0810fitrianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- IG1 Element 3 Key Learning PointsDocument4 paginiIG1 Element 3 Key Learning PointsPatryk KuzminskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engaging: Employees EmployeesDocument9 paginiEngaging: Employees EmployeesLarín AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 305 Group ProjectDocument9 pagini305 Group ProjectHunter BaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior-Based Safety Approach at A Large Construction Site in IranDocument5 paginiBehavior-Based Safety Approach at A Large Construction Site in IranSakinah Mhd ShukreeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implementation of Fire Safety Management System at Dr. Sobirin Hospital District of Musi Rawas 2013Document5 paginiImplementation of Fire Safety Management System at Dr. Sobirin Hospital District of Musi Rawas 2013baiqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ohsc Assignment 5Document5 paginiOhsc Assignment 5Kumar MangalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- NEBOSH IGC1 Health and Safety Policy ElementsDocument26 paginiNEBOSH IGC1 Health and Safety Policy ElementsShahzaibUsman100% (1)

- PR1 ReyesDocument7 paginiPR1 ReyesflorenciaebcayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior Based SafetyDocument13 paginiBehavior Based SafetyRusihan HSE100% (1)

- Risk Based Process SafetyDocument5 paginiRisk Based Process Safetykanakarao1Încă nu există evaluări

- Sms Quality HerreroDocument20 paginiSms Quality HerreroHandaru PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety and Health at Work: Feyzan Arikan, Songul K. SozenDocument13 paginiSafety and Health at Work: Feyzan Arikan, Songul K. SozenNurfadilah SuhadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- NR 17 - Participação Dos Trabalhadores Tendo em Vista Prevenir Lesões Musculoesqueléticas Na Montagem de CaldeirasDocument5 paginiNR 17 - Participação Dos Trabalhadores Tendo em Vista Prevenir Lesões Musculoesqueléticas Na Montagem de CaldeirasCPSSTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Assignment 1Document8 paginiQuestion Assignment 1Moiz AntariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 1: Key Elements of Health and Safety Management SystemDocument26 paginiTopic 1: Key Elements of Health and Safety Management SystemOgunsona Subomi KejiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annexure-V Cover for Academic Tasks in ITDocument11 paginiAnnexure-V Cover for Academic Tasks in ITvedang bhasinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Looking For Higher Standards: Behavioural Safety - Improving PerformanceDocument16 paginiLooking For Higher Standards: Behavioural Safety - Improving PerformanceHelp Tubestar Crew100% (1)

- Topic 3Document8 paginiTopic 3Francis Albert Samantila GimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- MOCK QP 2 Answer SheetDocument7 paginiMOCK QP 2 Answer SheetPradeep100% (1)

- Proceeding 2Document102 paginiProceeding 2userscribd2011Încă nu există evaluări

- Behavioural SafetyDocument23 paginiBehavioural Safetybishal pradhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organizational Changes: Management Skill. A Guiding Principle When Drawing Up Arrangements For SecuringDocument5 paginiOrganizational Changes: Management Skill. A Guiding Principle When Drawing Up Arrangements For SecuringAnkita OmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Ergonomics Program PDFDocument18 paginiSample Ergonomics Program PDFSyv Consultores AsociadosÎncă nu există evaluări

- HEPS2011 Reiman Pietikainen Patient Safety Culture SurveyDocument4 paginiHEPS2011 Reiman Pietikainen Patient Safety Culture SurveyTeemu ReimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit-III SafetyDocument38 paginiUnit-III SafetySudarshan GopalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Culture Impact On Pilots For Major Middle Eastern Airlines Company Part 1Document12 paginiSafety Culture Impact On Pilots For Major Middle Eastern Airlines Company Part 1Akram NahriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bsbwhs401summative 1 2020Document3 paginiBsbwhs401summative 1 2020LAN LÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavior Based SafetyDocument20 paginiBehavior Based SafetySuriyansyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental and SocialDocument9 paginiEnvironmental and SocialTariku BalangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 16 - Monitoring, Review and Audit by Frank WarehamDocument13 paginiUnit 16 - Monitoring, Review and Audit by Frank WarehamUmar ZadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BBS PDFDocument3 paginiBBS PDFValentinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dimensions of The Architecture of Safety ExcellenceDocument6 paginiDimensions of The Architecture of Safety ExcellenceGissmo100% (1)

- Behavioral Based SafetyDocument14 paginiBehavioral Based SafetyZekie LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- KTM KOMUTER FARES EFFECTIVE DEC 2ND 2015Document1 paginăKTM KOMUTER FARES EFFECTIVE DEC 2ND 2015Hamka HidayahÎncă nu există evaluări

- How to make chemical solutions from solidsDocument6 paginiHow to make chemical solutions from solidsMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab SignageDocument11 paginiLab SignageMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matecconf Ibcc2016 00107Document9 paginiMatecconf Ibcc2016 00107Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- KLSM KBSM KSSMDocument1 paginăKLSM KBSM KSSMMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Job Application Form - IIUM SchoolsDocument1 paginăJob Application Form - IIUM SchoolsMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Teknologi: Nilai Profesionalisme Bakal Guru Berteraskan Indikator Standard Guru Malaysia (SGM)Document7 paginiJurnal Teknologi: Nilai Profesionalisme Bakal Guru Berteraskan Indikator Standard Guru Malaysia (SGM)jayanthanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jilid 11 Artikel 01Document15 paginiJilid 11 Artikel 01munirahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Job Application FormDocument4 paginiJob Application FormMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction Safety Assessment Framework For Developing Countries: A Case Study of Sri LankaDocument19 paginiConstruction Safety Assessment Framework For Developing Countries: A Case Study of Sri LankaMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ask Bab 3Document50 paginiAsk Bab 3Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizwan 2015Document63 paginiRizwan 2015Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Form Osh Award 2016Document23 paginiApplication Form Osh Award 2016Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ujian Mac TMP Tahun 5Document89 paginiUjian Mac TMP Tahun 5Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction Safety and Health Factors at The Industry Level: The Case of SingaporeDocument19 paginiConstruction Safety and Health Factors at The Industry Level: The Case of SingaporeMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper Keng RazakDocument19 paginiPaper Keng RazakNur MajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methodologies For Studying The Informal Aspects of Construction Project Organisations Thayaparan GajendranDocument15 paginiResearch Methodologies For Studying The Informal Aspects of Construction Project Organisations Thayaparan GajendranMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch2 Literature ReviewDocument11 paginiCh2 Literature ReviewMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijaiem 2015 01 11 16Document10 paginiIjaiem 2015 01 11 16International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methodologies For Studying The Informal Aspects of Construction Project Organisations Thayaparan GajendranDocument15 paginiResearch Methodologies For Studying The Informal Aspects of Construction Project Organisations Thayaparan GajendranMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenges and Needs For Support in Managing Occupational Health and Safety From Managers' ViewpointsDocument21 paginiChallenges and Needs For Support in Managing Occupational Health and Safety From Managers' ViewpointsMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- TS07K Muiruri Mulinge 6847 PDFDocument14 paginiTS07K Muiruri Mulinge 6847 PDFMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijerph 14 00045Document17 paginiIjerph 14 00045Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper Keng RazakDocument19 paginiPaper Keng RazakNur MajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizwan 2015Document63 paginiRizwan 2015Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- TS07K Muiruri Mulinge 6847 PDFDocument14 paginiTS07K Muiruri Mulinge 6847 PDFMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- 555Document4 pagini555Mohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijaiem 2015 01 11 16Document10 paginiIjaiem 2015 01 11 16International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction Safety Assessment Framework For Developing Countries: A Case Study of Sri LankaDocument19 paginiConstruction Safety Assessment Framework For Developing Countries: A Case Study of Sri LankaMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Safety and Health Measures (Shassic Method) in Construction SitesDocument9 paginiAssessment of Safety and Health Measures (Shassic Method) in Construction SitesMohd Yazid Mohamad YunusÎncă nu există evaluări

- AVR R448: SpecificationDocument2 paginiAVR R448: SpecificationAish MohammedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stheory Balagtas Activity Lesson 15Document6 paginiStheory Balagtas Activity Lesson 15xVlad LedesmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrical Plant Load AnalysisDocument36 paginiElectrical Plant Load AnalysisJesus EspinozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 4 - Chemical Kinetics 4b - Half LifeDocument20 paginiTopic 4 - Chemical Kinetics 4b - Half LifeJoshua LaBordeÎncă nu există evaluări

- SQL Injection Attack Detection and Preve PDFDocument12 paginiSQL Injection Attack Detection and Preve PDFPramono PramonoÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Biology 1: Quarter 2 - Module 1 Energy TransformationDocument41 paginiGeneral Biology 1: Quarter 2 - Module 1 Energy TransformationAyesh MontefalcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- EE6010-High Voltage Direct Current TransmissionDocument12 paginiEE6010-High Voltage Direct Current Transmissionabish abish0% (1)

- Aditya Rahul Final Report PDFDocument110 paginiAditya Rahul Final Report PDFarchitectfemil6663Încă nu există evaluări

- EECIM01 Course MaterialDocument90 paginiEECIM01 Course Materialsmahesh_1980Încă nu există evaluări

- Endothermic Reactions Absorb HeatDocument2 paginiEndothermic Reactions Absorb HeatRista WaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lec11 Amortized Loans Homework SolutionsDocument3 paginiLec11 Amortized Loans Homework SolutionsJerickson MauricioÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIS 14665 Part 2Document6 paginiBIS 14665 Part 2Sunil ChadhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plain Bearings Made From Engineering PlasticsDocument44 paginiPlain Bearings Made From Engineering PlasticsJani LahdelmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mobile GIS Platforms and Applications with ArcGISDocument28 paginiMobile GIS Platforms and Applications with ArcGISZachary Perkins100% (1)

- Lesson Statement Sheet.Document2 paginiLesson Statement Sheet.Anya AshuÎncă nu există evaluări

- BUS STAT Chapter-3 Freq DistributionDocument5 paginiBUS STAT Chapter-3 Freq DistributionolmezestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experiment List (FEE)Document5 paginiExperiment List (FEE)bpkeleÎncă nu există evaluări

- R Fulltext01Document136 paginiR Fulltext01vhj gbhjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Temperature Effect On Voc and IscDocument5 paginiTemperature Effect On Voc and IscAnonymous bVLovsnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tetrahydrofuran: THF (Disambiguation)Document12 paginiTetrahydrofuran: THF (Disambiguation)Faris NaufalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Name Source Description Syntax Par, Frequency, Basis)Document12 paginiName Source Description Syntax Par, Frequency, Basis)alsaban_7Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Eligible Candidates Applied For Registration of Secb After Winter 2015 Examinations The Institution of Engineers (India)Document9 paginiList of Eligible Candidates Applied For Registration of Secb After Winter 2015 Examinations The Institution of Engineers (India)Sateesh NayaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blockaura Token 3.1: Serial No. 2022100500012015 Presented by Fairyproof October 5, 2022Document17 paginiBlockaura Token 3.1: Serial No. 2022100500012015 Presented by Fairyproof October 5, 2022shrihari pravinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trafo 40 Mva PDFDocument719 paginiTrafo 40 Mva PDFeug_manu8Încă nu există evaluări

- Uptime Awards: Recognizing The Best of The Best!Document40 paginiUptime Awards: Recognizing The Best of The Best!Eric Sonny García AngelesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 10 Windows Firewall Netsh CommandsDocument4 paginiTop 10 Windows Firewall Netsh CommandsedsoncalleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deep Glow v1.4.6 ManualDocument6 paginiDeep Glow v1.4.6 ManualWARRIOR FF100% (1)

- Lesson Planning Product-Based Performance TaskDocument8 paginiLesson Planning Product-Based Performance TaskMaricarElizagaFontanilla-LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Research Approaches and Designs - An Overview - Amoud - 2020Document18 paginiBasic Research Approaches and Designs - An Overview - Amoud - 2020Haaji CommandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Sheet - Item Number: 750-8212/025-002 Controller PFC200 2nd Generation 2 X ETHERNET, RS-232/-485 Telecontrol Technology Ext. Temperature ECODocument20 paginiData Sheet - Item Number: 750-8212/025-002 Controller PFC200 2nd Generation 2 X ETHERNET, RS-232/-485 Telecontrol Technology Ext. Temperature ECOdiengovÎncă nu există evaluări