Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Mitsuya Mori: The Structure of Theater: A Japanese View of Theatricality

Încărcat de

CincacskaDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Mitsuya Mori: The Structure of Theater: A Japanese View of Theatricality

Încărcat de

CincacskaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Japanese View of Theatricality 73

The Structure of Theater :

A Japanese View of Theatricality

Mitsuya Mori

The Western concept of “theater” did not exist in pre-modern Japan.

Engeki was the word chosen to translate “theater” when it was introduced

to Japan in the second half of 19th century.1 It still sounds a little foreign to

Japanese people. Traditionally Japan had a word shibai, which was almost

equivalent to “theater,” but was, and still is, applied only to Kabuki and

Bunraku (puppet theater) and not to Noh. The modern westernized theater

is not usually called shibai, either, for this sounds too colloquial or too non-

literal. The adjective forms of shibai, shibai-jimita or shibai-gakatta, imply

“pretentious” or “insincere” behavior, a definitely pejorative nuance,

equivalent to the negative meaning of the English term “theatrical.”

“Theatricality,” on the other hand, is rendered in Japanese as engeki-sei.

The suffix -sei makes an abstraction of the preceding noun. The foreignness

of engeki is reinforced by this suffix, for the abstraction of theatricality is also

a Western way of thinking, imported into Japan only in modern times.

Grammatically, it would be possible to add -sei to shibai as well, but shibai-sei

sounds odd and is not in common usage. This means that there is no Japanese

word that is exactly equivalent to the slightly pejorative “theatricality.”

Instead, engeki-sei (theatricality) is used to mean the spectacular quality of

theater, or the qualities unique to theater—i.e. particular qualities that

construct the kind of performance we could call theater. It is in this sense

that the word was often uttered to describe the new trend of Japanese theater

since the late 1960s. But some representatives of this “underground” theater

would like to call their activities shibai rather than engeki, as a revolt against

“modern theater.” They have even declared themselves to be closer to the

old conception of performance art in Japan, geinoh.

Geinoh (“gay-noh”) is another Japanese word, fairly equivalent to

“theater” but covering the broader or narrower realm of performance arts,

depending on the context. (I will return to this issue later.) Though the word

itself first appeared in literature in the 10th century,2 much earlier than shibai,

today the word is also commonly used, and obviously intersects with engeki-

sei. The distinction between engeki, shibai and geinoh is not a clear-cut one,

© Board of Regents, University of Wisconsin System, 2002 73

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

74 Mitsuya Mori

and it becomes almost meaningless to attempt to define the words at all.

(Such confusion is an inevitable result of modernization, and is seen in many

fields of culture in Japan.) But if our goal is not simply defining terms, but

understanding what theater is, then we need to move beyond the definition

of concepts. Our understanding of the topics will be deepened in the course

of discussing them. Our topics are theater and theater-like performances,

which still exist in abundance in Japan.

There are many ways to analyze theater. I will limit my arguments here

to the structural analysis of theater events—i.e. basic characteristics of theater

to be distinguished from other performative activities, in order to clarify

“theatricality” to some degree.

From Creator to Audience

Theater is play and so is music. As an art form, theater and music have

some structural similarities. In the aesthetic classification of art forms, theater

and music are put into the same category—performing arts.

A composer writes a piece of music, which is perceived by someone

else. This “someone else” is usually a musician who plays the score to be

perceived by the audience. This sequence can be schematized as follows:

Composer —> Musical Composition —> Score reader

Musician—> Musical performance —> Audience

The upper and the lower levels have a similar structure in the way they are

produced. For this reason, music is called an art form of “double

productions.”

Different musicians may play the same score differently, but it would

not be unreasonable to say that what the composer composes and what the

musician plays are almost the same. In a competition of musical composition,

the nominated works are performed in front of the judges. What the audience

finally perceives is supposed to be the same as what the composer originally

had in mind. The audience and the composer share the same artistic

experience. We can modify the diagram to the cyclic structure as follows:

Composer —> Musical Composition —> Score reader

Audience <— Musical performance <— Musician

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 75

The second production repeats the first one but in reverse.

Theater is also an art form of double productions. Therefore, on the

surface, the analysis of its structure is similar to that of music.

Dramatist —> Drama —> Drama reader

Actor—> theater performance—> Spectator

However, unlike music, the second production does not repeat the first one

in reverse. A theater performance onstage is quite different from a drama on

paper, and what the spectator conceives is not at all the same as what the

dramatist had in mind. It used to be said that the dramatist imagines the

stage production as he writes, so that one can read in the drama—provided

it is a good one—every detail of the stage production. Obviously this is

wrong. Even the realist Ibsen would not possibly have imagined the way A

Doll’s House or Ghosts might be performed today. This is because a theater

production is a combination of two different aspects: drama and play. I have

detailed these aspects elsewhere (Mori, 1997), but it is primarily the play

aspect that makes the difference between what the dramatist writes on paper

and what the actor performs onstage.

If what the musician plays is fairly much the same as what the composer

composes, the above written diagram of the music structure could be as

simple as this:

Composer —> Musical Piece (Score-Musician-Playing) —> Audience

But the diagram of theater structure cannot be shortened. It remains:

Dramatist—> Drama —> Actor —> Playing —> Audience

Structurally speaking, the musician is a mediator between the composer

and the audience or an interpreter of the score (a musical performance is

sometimes called an interpretation), while the actor is a creator of a kind of

art form that is different from a written drama. This is another way of saying

that music depends only on our sense of hearing, but theater on both hearing

and sight. True, we enjoy the pianist’s passion-filled bodily movements, but

the sight is not supposed to affect our evaluation of his or her musical

performance.

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

76 Mitsuya Mori

Actor Plays Character for Audience

The unique feature of theater lies in its process of performance. Hence

any discussion of theater tends to focus on the performance level. Peter Brook

says in the opening passage of his The Empty Space, “A man walks across

[...the] empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that

is needed for an act of theater to be engaged” (9). This statement is rather

misleading. The man who crosses the empty space may be an actor and the

man who watches him a spectator, but Brook mentions no character that the

actor plays. Nevertheless, the man’s action of crossing the empty space

implies his playing something or somebody else. Therefore, we can find

even in Brook’s statement three basic elements of theater: Actor plays

Character for Audience.

Admittedly, this formula has been challenged in the second half of the

20th century, and various theaters, which seemingly lack one of those

elements, have been advocated and practiced. But it seems that no one has

proposed more than these three as the primary agents composing a theatrical

event. So, this formula can still be a good point of departure.

First, the relationship between these three elements is to be seen not as

linear but as triangular. The diagram can be drawn thus:

A(ctor) —————— C(haracter)

Au(dience)

This kind of triangular relationship is meaningless in art forms other than

theater. The impossibility of technological reproduction of a theater

performance also derives from this structural relationship.

This triangular diagram may be viewed in two ways: either from each

corner point, or from each line between the two corners. The latter view is

preferred here, for in this way we have a chance to grasp a theater production

as a whole without cutting it up into pieces to be examined one by one. If we

look into the triangle from the line between A and C, for example, we see Au

beyond the line so that Au is not at any moment excluded from our view of

the A-C relationship. In this way the whole theatrical event could be viewed,

if not in its completeness, at least adequately enough.

Each line of the triangle—i.e. the relationship between each two of the

three agents—is closely related with each of the three basic aspects of theater:

playing, drama, theatrical space. The relationship between Actor and

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 77

Audience transforms a physical place, where they simultaneously exist, into

a theatrical space. The aspect of playing stands in the relationship between

Actor and Character, and Drama is not something Actor presents to Audience,

but something formed between Audience and Character. The triangular

diagram, therefore, can be enriched as follows:

playing

A ——— C

space —> <— drama

Au

Creating a Theatrical Space

When and how is a physical place transformed into a theatrical space?

Peter Brook refers to empty space as if it exists before a man crosses over it.

But “empty space” does not exist in this world. In both an open-air theater

and a proscenium-arch theater, many things have been in existence before

the man crosses over the space. In fact, it is the man’s crossing it that makes

the place into the “empty space” for the one who watches. The actor’s action

makes every pre-existing thing (except those set up for his action) invisible

to the audience.

This is apparent particularly in the indoor theater, which became

common in the 18th century, both in Europe and in Japan. Before that, most

theatrical performances took place in open- or semi-open-air theaters,

surrounded by nature. In some Greek theaters the audience could have a

view of a natural landscape or townscape beyond the skene (Carlson, 62).

One of the oldest Noh stages in Japan stands in seawater, and the audience,

sitting in another building, can notice the sea-level change as the performance

proceeds. Even the Shakespearean theater, already encircled by walls, must

have made best use of the effect of the movement of the sun during the

performance. I would like to call this characteristic of the theatrical place

“field” in contrast to empty “space.” It is an interesting coincidence that

both European and Japanese theater history had a transition from “field” to

“space” in the 16th and 17th centuries. In Europe in this period, the tradition

of medieval drama lost its vigor and modern secular drama came to be

formed, while in Japan, the long-established Noh drama made room for the

newly-emerging Kabuki theater form. Apparently, on both sides, this change

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

78 Mitsuya Mori

was reinforced by a new type of dramatic character on the stage—a type

that was more realistic than in previous dramas.

The “space” characteristic of the stage is closely related to realism in

theater. Realism demands that the audience ignore the pre-existing

decorations and forms of the stage and see characters as if they were really

living there. The more realistic the drama becomes, the more the stage is

required to be “space,” and vice versa. The “space” also cosmopolitanizes

drama, because a drama’s “space” can be transferred to any other theater

without essential alterations. This was not possible for Shakespearean drama,

for example, which still retained the “field” aspect to a considerable degree.

Nevertheless, a physical place cannot transform itself into a theatrical

place without acquiring aspects characteristic of “space.” An absolute “field”

will remain a natural place of daily life. Thus the question, “When and how

is the physical place transformed to theatrical space?” can be modified to,

“When and how is field transformed into space?”

Field and Performance

The “field” aspect of the performing place is nowhere more apparent

than in folkloric rituals, which still today are regularly seen in Japan and

other Asian countries. The place can be a rice field, the area around a shrine,

a village market place, etc. Every ritual must be performed in its particular

“field” and cannot be moved to any other place.

However, the “field” of the ritual is not a mere natural, everyday field.

An actual rice field, which is chosen for the rice ritual on a specific day of

the year, is decorated in a special way for the performance by girls selected

in the village for this occasion. This is no longer an ordinary rice field, but

the one devoted to a divine being in a wish to have a good harvest, not only

for this particular field, but for all the fields in the village. The “space” aspect

already creeps in here. The selected girl performers and the surrounding

village people have a special relationship with each other in their wishes,

which transforms this rice field into a ritual space or, we may say, a theatrical

space.

Let us take another example. A ritual performance at the Nigatsu-do

Hall of the Todaiji Temple in Nara is called Todaiji-shunie and takes place in

the middle of March. The climax comes after dark. Monks carry eight or

nine burning torches (ca. 10 meters long and half a meter in diameter), each

held by several monks, up to the wooden veranda of the Hall, about 20

meters above ground level. They are laid side by side on the edge of the

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 79

floor, the burning heads being thrust in the air. Hundreds of thousands of

people come to watch this performance, standing on the ground below, so

that sparks of fire fall upon them. This is truly a spectacular sight. While the

torches are burning on the veranda, a group of monks conducts a special

rite in a small room inside the Hall. They continue the rite all night long,

sometimes sitting on the floor, sometimes walking or jumping around an

altar, but all the time chanting prayers. At around three o’clock in the

morning, a monk brings another burning torch into this small room and hits

the wooden floor with full force. Sparks of fire spread out and monks jump

over them. This is an incredible performance, even more spectacular than

the performance outside. Only those who have obtained special permission

from the Temple are allowed to witness this rite from a side room. No women

are allowed. They must remain outside, but may watch through a grill. The

monks completely ignore the spectators, the rite being conducted first and

foremost for themselves. I cannot deny the great excitement I felt when I

saw the enactment of this rite. And yet I had no personal feeling toward the

monks, but rather an impression of a great panoramic picture, like an erupting

volcano or an awesome ocean wave. It was an event completely of another

world, so to speak, which we were peeping into; similar to a cinematic

experience rather than a theatrical one. No definite theatrical relationship

between the performers and the spectators was formed.

It was different in the case of the ritual that I once experienced in the

region of Kofu, in central Japan. The performance took place inside curtain

walls set up around the village shrine, so that the performance was totally

hidden from the spectators. Nevertheless, we, standing outside, clearly felt

related to those performers inside. I say “we” because I could sense the

festive atmosphere prevailing among us while waiting for the end of the

performance. This feeling, I assume, came from the fact that we had talked

with the village performers and had walked behind them to the shrine before

the performance. The whole process was a ritual, only a part of which was

the performance inside the curtain walls. So we were participating in the

ritual not only by having followed them to the shrine, but also by waiting

outside the curtain walls. It was odd indeed that we had a feeling of being

related to the performers whom we could not see—a kind of feeling one did

not have for the other performers whose spectacular action had made an

awesome impression. Although I did not share the belief of the village people

in their divine being, I at least could understand their belief. Herein lies the

crucial point of our relationship. Both I and the village people perceived

something existing outside our relationship, or better said, something that

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

80 Mitsuya Mori

assured our close relationship. Even if it is doubtful that this “something”

could be called Character in our diagram of the theater structure, it was,

without doubt, because of this “something” that the area of the village shrine

became a theatrical space, which the small room for the rite in the Nigatsu-

do Hall was not. I had been struck by the sight of the monks’ performances,

but almost completely alienated from their belief.

Without at least a glimpse of C, the relationship will be reduced to that

of Player-Spectator. I mean by “Player” the performer who performs for

him/herself, and by “Spectator,” the one who watches the performance as a

mere bystander. The Player—Spectator relationship is, in fact, no relationship.

This is the case with sports, games or music. Some sports, and certainly

music, are played for spectators (or listeners), and some may claim that

musical performers are influenced by the audience’s responses. This is true

especially in popular music concerts, but these come close to being theater

performances. Spectators are not essential for players of music, nor are

players necessary for “spectators.” We enjoy recorded music as a substitute

for live performances, even if it is not a completely satisfactory one. This is

not the case with theater, as anyone knows.

Actor and Character

The relationship between Actor and Character is the most problematic

one in the triangular structure of theater. We say that an actor plays a character,

but this activity is called acting. The difference between playing and acting

corresponds to the distinction between Player and Actor, respectively. Acting

implies “playing a character,” but the “play” element, being situated between

Actor and Character, stands independent of both. In actuality, A, p and C

are combined together in a person acting in front of the audience, but in

theory these three can be separately examined. I have done so in some detail

on another occasion, basing my arguments on the following schema (Mori,

1997):

A(ctor) —— p(lay) —— C(haracter)

Au(dience)

As is easily understood, realistic theater tends to hide p, or tries to make

p unseen to Au. In non-realistic, or stylized, theater, p is emphasized rather

than hidden, and when a certain pattern or form of p is repeated by one

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 81

actor or one generation of actors after another, what is called kata in Japanese

is born. This is the case with the stylized movements in Kabuki and Noh.3

And the traditional puppet theater in Japan, today called Bunraku, is an

interesting example by which we can illustrate each element of this scheme—

A, p and C—not in theory, but in actuality.

Any puppet theater consists of three basic elements: the puppeteer, the

puppet, and the narrator. The puppeteer manipulates the puppet according

to the dialogue or narrative spoken by the narrator. In most puppet theaters

the puppeteer and the narrator are the same person who hides himself from

the audience so that they see only the puppet. But in Bunraku, all three

elements are in sight. The narrator chants the story with the shami-sen (three-

stringed instrument) musical accompaniment, played by a shami-sen player.

Both narrator and musician sit side by side on the small platform, stage-left.

A puppet is two-thirds the size of an actual human being, and is operated

by hand by three puppeteers; the main puppeteer handles the head and the

right hand, the second the left hand, and the third, the legs. Usually

puppeteers cover their heads and bodies in black so as not to distract the

audience’s attention from the puppets, but curiously enough, the main

puppeteer shows his face in important, dramatic scenes of the play.

These three elements of Bunraku—puppeteer, puppet and narrator (with

music player)—correspond to the above-schematized three structural

elements of acting, A, p and C, respectively. This rare case of Bunraku reveals

that C cannot be a theatrical element without being bodily expressed by p,

and that p could not be theatrical p, no matter how stylized it may be, without

being framed by C. But the most interesting thing to see is that A and p are

indeed two separate entities in acting. The Audience can see p without paying

attention to A, or even both A and p at the same time but separately. The

audience can see all the structural elements of theater performance

independently. In this respect Bunraku manifests the most basic structural

characteristic of theater performance.

Of course this manifestation is not possible in an ordinary theater. But

what is really revealing in Bunraku for the present argument is the fact that

A does not play C in the sense that A’s movements represent C to Au. Au

watches p, or A and p together, but C is given independently from a different

side. In Bunraku, what the narrator chants is not only the dialogue of the

characters but the whole narrative story. It can be appreciated as a free-

standing form of literature. Herein lies a key to the everlasting question

concerning acting: is it the actor or the character that the audience is watching

on the stage?

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

82 Mitsuya Mori

Actor/Character

Our perceptive organs can perceive only one object at a time, never two

or more. It is not possible for us to watch both the actor and the character at

the same time. Some think that we watch them alternately. But this is absurd,

for then the character is split into pieces, and each member of the audience

may have entirely different portions of the character. Some also think that

the actor is a real person and the character an imaginary one, so that both

are compatible. But real or imaginary, we cannot perceive two objects at the

same time. What is wrong about the above-asked question is the

presupposition that character is a “person,” real or imaginary. For in fact, a

character is not a person but a conception, which is formed in the audience’s

mind.

When a person appears on the stage, we notice him, of course, but do

not know if he is an actor playing a character or not. He may be the man we

call Hamlet, but he may turn out to be the man who is going to apologize for

the delay of the performance. Even a man who we suppose is playing Hamlet

can take off his pretence at any moment and come back to himself as an

actor. This means that we cannot be sure of having a complete character

until the final curtain falls. We have a character only when the play ends.

But when the play ends, the character is gone. He remains only in our minds,

as a conception. Therefore, we may say that, watching the movements of the

actor and hearing his lines, we build up the conception of the character little

by little. Sometimes he may surprise us by an action, which his previous

behavior had not led us to expect from him, but we adjust our hitherto built-

up character to that new behavior and amend the conception accordingly.

No matter how much his behavior confuses us at a certain moment in the

play, we get a total conception of the character at the end. If we do not, we

feel that the character is incomprehensible.

Although everything in theater is pretense, a pretense that the audience

is well aware of all the time, the audience can believe in the character all the

same. This belief is supported by the fact that a man on the stage is a real

human being, which is not the case in cinema or the novel. So, coming back

to the question of actor-character confusion, the audience’s illusion of

character is based on the reality of the actor’s being. And if Character is a

conception that we complete only at the end of the play, it is to be understood

in the genuine sense of the word “character”—ethos in Greek.

Aristotle put the primary importance on mythos rather than ethos, in his

analysis of Greek tragedy in the Poetics. Mythos, usually rendered into English

as plot, is a series of actions. Hence his definition: “Tragedy is a representation

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 83

of an action.” But we humans have the amazing ability to discern the plot of

a play that consists only of dialogues. In a theater, we hear only actors’ lines,

with no explanations by the author or any one else, but we can still discern

the story of the play as if it were narrated. This ability is obviously related to

our ability to understand language. In the same way that we conceive the

meaning of a sentence in a linear sequence of words, we weave the texture

of the story little by little as we see actions going on. The story grows bigger

and bigger from the series of small stories within each scene, until we get

the whole story—the plot of the play—at the final curtain.

If the series of actions does not form a plot, everything we see is on the

level of bare reality, and there is no formation of character, either. If one

were to diagram the formation of both character and plot, they would be the

same, since character and plot are actually one and the same thing. A

character cannot stand alone, but can exist only in relation to other

characters.4 That a character is complete at the end of the play means that all

the relationships between characters are completed, which is nothing but

the plot of the play. We make up a character, little by little, in our minds, as

we gradually make up the plot. Here arises the question of Drama. But before

pursuing this question, I would like to take a couple of examples to illustrate

how reality and fictionality intersect on the stage.

Reality and Fictionality

There is a scene in a Noh play, Dojoji, where an actor seems to step out

of the realm of the fictional world into reality. In this scene, called ran-byoshi,

the shite (main role) makes stamping movements in accord with the drum

music, played by one of the four musicians sitting on the floor upstage. The

shite of this play is a female entertainer who has been infatuated with, but

deserted by, a young priest, and who chases after him to the temple where

he hides himself. At the temple, the celebration of the completion of a new

bell is held, but the female entertainer’s jealous passion makes the bell fall

down. She transforms herself into an evil snake inside the bell and comes

out only to be soothed by a priest. The scene ran-byoshi takes place right

before the fall of the bell. When the play reaches this scene, the player of the

small drum changes his posture so that he directly faces the shite, who is

standing beside the right pillar, downstage. Usually the musicians, facing

toward the main auditorium, pay no attention to the players. In this scene,

subtle movements of the shite’s feet, stamping on the floor, and sporadic

sounds of the small drum are in accord and discord with each other, as if

both players were engaged in a battle of life and death. Each of them is

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

84 Mitsuya Mori

concentrating greatly, the actor on the timing of his movements and the

musician on the beating of the drum. The fictional plane of the play

disappears for several minutes of this scene, and the audience senses both

players existing on the plane of reality.

A sudden stepping out of the fictional world happens more often in

Kabuki, and in a more festive mood. The typical one is koh-joh, a scene where

actors on stage pay the audience ceremonial greetings on the occasion of the

succession of a big actor’s name by a junior one.5 A koh-joh scene sometimes

takes place in the middle of the play; that is to say, all the actors on the stage

at the moment, who are usually the young one’s family and relatives, stop

acting all of a sudden and sit in a horizontal line on the stage to greet the

audience one by one. After the greetings are finished, they resume acting

and the play continues. It is even more obvious here than in ran-byoshi of

Noh, that we see actors in reality rather than characters in fiction.

However, if, as we have discussed, character is not a person but a

conception that the audience conceives in the course of the performance,

and if character is in fact the same as the plot, these scenes of Noh and

Kabuki, which seem to be carried out on the plane of reality in the middle of

the play, should also be included in the conception of character and plot.

Indeed, in these scenes actors do not change their costumes, and their

actions—stampings or greetings—are still very stylized. They are definitely

in kata. Therefore, the plane of reality that suddenly manifests itself in these

scenes is not everyday reality, but reality in fiction, one may say. It is a

theatrical device to make the audience realize that in theater, reality and

fiction are interwoven in a complicated fashion. And it is at this moment

that the audiences of Noh and Kabuki have the feeling of utmost theatricality

(engeki-sei), a feeling that we rarely get from any other art form.6

Drama

Audience builds up Character, which is identical to Plot. This

identification of Character and Plot forms Drama. Drama here is not the

drama the playwright writes. In my definition, Plot and Drama are the same

as Story, but Drama is an expression of a view of life, while Plot is a series of

actions. Drama emerges from Plot and yet is a larger world than Plot. We

can get a plot out of what the playwright writes (what a playwright writes

is also a series of dialogues, and the reader composes the plot of the play in

the same way that the audience does it from the lines spoken by the actors),

but Drama must be formed in theater—that is, from actual actions on the

stage.

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 85

Drama has been the subject of elaborate discussions among literary

critics, and we do not need to go through them. But a few observations on

Japanese theater may be of some use for our discussion on theatricality.

When drama was invented as the form of Noh in Japan, it was not the

same as Greek Tragedy or any later Western drama. Noh consists not only of

dialogues, but—more important—of narrative and lyric forms. Lines include

explanatory descriptions (or stage-directions) and the words of the chorus

(ji-utai) of eight chanters, sitting stage-left, who speak sometimes as pure

narrator and sometimes in unison with the main character, shite, who also

partly narrates his actions by himself. Therefore Plot is not formed by, but

given to, Audience as in an epic. Nevertheless, an abyss lies between the

participatory role of Audience in Noh, and that of the earlier performative

forms of narrative and lyric (both were performed in all countries in pre-

modern times). While the latter could be totally passive in perception of the

narrative story or lyrical poetry, the former (Audience in Noh) is supposed

to conceive the extended world of poetry, only a small portion of which is

enacted or narrated on the stage. This world is Drama in Noh. In typical

Noh plays (though the present repertories of about 220 plays contain many

different kinds), the shite is a dead person appearing in this world from an

old literary world such as The Tale of Genji or The Tales of Ise, or from an

historical epic of major battles such as The Tale of the Heike or Taihei-ki. The

play is enacted in the present tense (otherwise it would not be drama), but

the story is given in the past tense because it is about a world from the past.

The shite, therefore, exists in both worlds, present and past, at the same time.

We conceive beyond the episodic story of the shite the entire world of the

tales or historical epics. When, for example, the wife of Narihira, the shite of

the most famous Noh play, Izutsu, looks down into the well and sees the

reflection of herself, whom she sees as her beloved husband (she is now

wearing Narihira’s clothes, in her yearning for him), we feel beyond her

longing the whole world of The Tales of Ise, a story about Narihira. More

than that, we sense the long tradition of Japanese poetry, for Narihira was

one of the best and most representative figures in Japanese poetry. In this

sense Noh calls for an active audience, which no performance art in Japan

did before.

Greek or European drama is primarily enactment of an action, which

looks forward to the future. Noh drama is enactment of a feeling, which

looks backward in the past. Or, better said, Noh makes no clear distinction

between the past and the present; characters come and go between the two

worlds. It has been pointed out that the Buddhist way of thinking lacks the

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

86 Mitsuya Mori

sense of history, which the Christian tradition clearly holds. In the Kamakura

Era, the period preceding the formation of Noh, new schools of Japanese

Buddhism emerged one after another. One of them was Japanese Zen, under

the influence of which Zeami was culturally educated. This may have

something to do with the above-stated characteristic of Noh drama.

When new forms of theater emerged around 1600 as Kabuki and

Nin’gyo-joruri (the original name of Bunraku), they did not have a pure

drama form, either. To be more precise, Kabuki did develop a drama form

of dialogue during its early stage, but in time it came under the dominance

of the Puppet Theater and adapted the puppet drama form to human actors;

actors play in part according to the narrative chanting. Most of the famous

Kabuki plays in the present repertories are of this type. Kabuki, though closest

to Western theater among the traditional theaters, acquired a pure drama

form in dialogue only in the second half of the 18th century. Before long,

however, it succumbed to the temptation of performing only some scenes

extracted from a long play, which originally had been performed from dawn

to twilight. Bunraku, too, follows this custom today.

Kabuki’s Plot, like Noh’s, is not identical with Character, but is composed

of dialogue and narrative (stage directions). In a sense, the story has been

given to the Audience beforehand. Most audiences know the play; if you do

not know the story of the play, you do not understand the scene. The primary

enjoyment results from the appreciation of the acting. And yet, just as the

Audience of Noh conceives a larger world beyond the shite, the Audience of

Kabuki appreciates the manifestation of a long tradition in the acting styles.

This larger world, Drama, keeps the Audience’s interest within the realm of

the Actor, rather than having it dispersed into mere interest in the Player.

Actor Plays Character for Audience

Having circumnavigated the triangle corners and lines of the theatrical

structure, we come back to the original formula: Actor plays Character for

Audience. But we have said that Character is only an abstract conception

that Audience completes at the final moment of the play. Is it not odd,

therefore, to say that Actor plays Character? However, when we say that an

actor plays, for example, Hamlet, what we actually mean is that he plays the

role of Hamlet. This “Hamlet” is no character in the sense we have discussed,

but a generally accepted image of a man called Hamlet in Shakespeare’s

Hamlet. Different actors play the same role of Hamlet but the audience

conceives different characters of Hamlet in different actors. The role of Hamlet

is a sort of stock character, like Pantalone, Arlecchino, or Dottore in commedia

dell’arte. He is not someone we conceive at the end of the play, but perceive

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 87

from the beginning. Roles are recognized in appearances and patterns of

movements and behaviors. In everyday life, we recognize Student, Teacher,

Priest, Fireman, etc. or more fundamentally, Man, Woman, Youth, Old Man,

etc. as roles. When small children play Father and Mother, these are roles,

too, not characters. As is commonly said, we are all playing roles of our own

in life.

Stock roles are common not only in commedia dell’arte or ancient Roman

comedy, but in most traditional Asian theaters. Each role has a distinct

appearance and its own patterns of behavior and movement, that is, kata. In

fact we are all behaving according to the kata most suitable to ourselves in

everyday life. Without this custom, the convention of female impersonation

in Kabuki or Elizabethan theater would be impossible. Role is an outer

feature, and Character is an inner quality. Role is a physical appearance,

and Character is a conceptual idea. In life and on the stage, Role and Character

are inseparable and together give us the complete person. Thus, we should

now amend our original triangle diagram as follows:

A —— C, R(ole)

Au

Note that Role or kata is nevertheless on the plane of abstraction, though

based on the level of everyday life. Different young men have different

patterns of behavior, but a certain typical pattern is abstracted from them

and called the role of the handsome young man. Character and Role are two

sides of a coin, a conception; they are not inseparable in actuality.

However, Character is equated with Plot, as we have seen, but Role is

not. Role is more on the side of reality, or, one may say, abstraction in reality.

It is possible that an actor plays the role of Hamlet without knowing the

character of Hamlet, or plot, only by moving as he was told to move, for the

patterns of his movement are decisive factors in the performance, out of

which Audience will compose Character and Plot. A famous Noh actor, who

had been greatly admired, confessed one day that he did not know the story

of the play he was playing on the stage. In Kabuki productions in the old

days each actor was given a script in which only his lines were written so

that he had no knowledge of the whole plot before the dress rehearsal. When

Role is the dominant factor in the C-R element, Plot tends to be fragmented;

it stands for the manifestation of Role rather than for Drama, the view of

life. This is exactly what has happened in Kabuki; today the usual Kabuki

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

88 Mitsuya Mori

repertories for an evening consist of three or four famous scenes taken from

long plays. When children are playing Father and Mother, it is of this type,

too; the important thing is being Father or Mother and not the story that

they play.

C is split into C and R in the new diagram. But this is nothing peculiar.

A and Au also have double faces. As was mentioned before, A contains a

“Player” aspect in itself and Au is endorsed by “Spectator.” So, the triangle

structure should be like this:

A(ctor), P(layer) ———— C(haracter), R(ole)

Au(dience), S(pectator)

The double faces of each corner element are inseparable, but the one

stands on the plane of fictionality and the other more on the side of reality.

Apparently Actor is related to Audience, which composes C, but Player is

seen by Spectator as a person who plays Role. The triangle of three pairs is

in fact two triangles, (a) and (b):

(a) (b)

P(layer) ———— R(ole) A(ctor) —— C(haracter)

S(pectator) Au(dience)

Any theatrical performance must have both structural triangles of (a)

and (b) together. Triangle (a) is more on the level of reality and (b) is more

on the level of fictionality. Because of its slant toward reality, triangle (a)

tends to exclude R, which is by nature not real but conceptual.

However, when (a) is reduced to a mere P-S relationship, it will be sports

or music. Player and Spectator do not necessarily communicate with each

other.

By the same logic, triangle (b) tends to ignore the existence of Actor,

which is on the plane of reality as a real human being. But when (b) comes

to be only a C-Au relationship, it will be a narrative or a novel. It needs

Actor’s performative aspect to be theater. Character is Character only by

being conceived by Audience as Plot, and Actor must be present in order to

make Plot theatrical.

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 89

To endorse the element of R in triangle (a), (a) needs (b), and (b) needs

(a) to assure A’s performative function. One may say that triangle (a) is a

triadic relationship—that is, we must look at the triangle from each corner

element, while triangle (b) is a tri-linear relationship—that is, we must look

at the triangle from each line between the corners. The ran-byoshi or koh-joh

scene seems to put more emphasis on (a) than (b) and makes the Player

aspect come forward because the fictional level is stripped away in these

scenes. But the Audience is never lost, for in the koh-joh scene in Kabuki, the

actors are directly addressing the Audience, and in the ran-bryoshi of Dojoji

everything is meant for the Audience. Noh actors look absolutely indifferent

to the audience when performing, but the goal of Noh is the satisfaction of

the audience, which Zeami called “making hana (flower) bloom.”

Being aware of the double triangle schemes of theater structure, we

may be able to clear away confusions that sometimes occur in theater

performances. When the Actor element is supposed to be emphasized, it

may, in fact, be the Player aspect that comes forth because of the lack of

Character. Or, when the Actor attempts to emphasize Plot, the emphasis

may actually be on Role, not on Character at all. New experimental theaters

are often entangled in two kinds of triangle relationship—the triadic and

the tri-linear—without being conscious of it.

Theatricality

Now we finally come to our main issue, theatricality. Theatricality is by

definition “being theater-like.” If theater is conceptually based on the

structural relationship between A-C-Au, it is the physical relationship of the

above-diagramed (a) that concretizes the conceptual (b) into an actual or

physical event, which is truly what we call theater. In short, it is the (a)

triangle that makes a performance of the (b) triangle. However, if the aspect

of (a) is too much in front, theater tends to be broken because of the loss of

fictionality. The less apparent the (a) is in a performance, the more we believe

in the plot in the (b), and it may be praised as a good theater of realism.

It seems that theatricality emerges when the (a) breaks into, and yet

does not destroy, the (b), that is, the (a) and the (b) are combined in the

stylized performance, which actually stands on the edge of ficitionality. A

spectacular scene or an acrobatic performance in theater, for example, gives

us a feeling of theatricality because of its manifestation of the (a) in the realm

of style, which actually is the (b).7 If traditional Japanese theater appears

rich in theatricality, it is because Japanese theater essentially appreciates the

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

90 Mitsuya Mori

aspect of (a) in style, as in the case of ran-byoshi in the Noh play, Dojoji, or the

koh-joh scene of Kabuki, discussed above.

This is the characteristic of what we call geinoh in Japanese, which I

mentioned in the beginning of this essay.

Geinoh or geinoh-jin (geinoh people) has in some contexts a pejorative

sense because it implies vulgarity or low artistic status. Modern theater would

refuse to be called geinoh. Geinoh covers traditional Japanese music

performances but never Western music (whose reviews in daily newspapers

usually appear in the culture section rather than geinoh section).

However, geinoh is often used in scholarly research works as a concept

to cover all the theatrical genres and performative activities, including the

tea ceremony and Sumo wrestling.8 Following the structural analysis we

have developed so far, we may say that geinoh includes every kind of

performance that contains the above schematized triangular structure of (a),

but that it needs even the slightest hint of the triangle of (b). Rituals have a

definite tendency to base themselves mainly on (a). But if they give us an

impression of geinoh, they always have certain aspects of (b). In the case of

the ritual performance, which was executed inside the curtain walls and out

of sight, we felt a definite relation to the performers, which means that we

were transformed from mere Spectator to Audience by something outside

us that we shared with the village people. This ritual performance definitely

falls into the category of geinoh. The rite in the Nigatsu-do Hall of the Todaiji-

Temple, on the other hand, refuses to let us be Audience. True, the monks in

the small room are no longer ordinary monks. They are playing sacred roles

that are quite different from their everyday roles. Nonetheless, they do not

go further to be totally characterized as Actor, and the rite remains on the

border between a geinoh and a purely religious rite.

Conventional theaters that hold a clear structural relationship of (b)

may dislike being classified as geinoh. But since triangle (b) could not stand

for a theatrical performance without (a), they, too, are categorized as geinoh.

Thus, geinoh requires: (1) the triangular structural relationship of (a),

Player-Role-Spectator, but (2) that at least one of these elements be lifted up

to the plane of the fictional relationship of triangle (b), Actor-Character-

Audience. Both traditional Japanese performances and Western experimental

ones tend to step out of the fictional plane of (b), but while the former still

keep the triangular structure with regards to the aspect of Audience, the

latter seem to put more emphasis on Actor in their own structure. Both share

the same intersection of reality and fictionality. Therefore, these Western

experimental performances give us a definite impression of being in the

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 91

realm of the geinoh even if they are rigorously trying to get rid of the

traditional structure of theater.

Thus, geinoh and theatricality go together, side by side. And whenever

the Western concept of “theater” suffers from narrowness and ambiguity,

the term geinoh may be recommended. Adopting this term, it will be possible

to denote the broader implication of theatricality as well as to make

distinctions between different kinds of performance, theatrical and non-

theatrical. Perhaps we need a new discipline of geinoh studies in order to

further explore the issue of theatricality.

Seijo University, Tokyo

Notes

1. Sino-Japanese characters for engeki did exist early in the 19th century, but labeled not as

engeki but as kyogen (see, Mori 2001).

2. The meaning of geinoh, which originally came from Chinese usage, first meant “skill,”

but went through a considerable degree of change from the 10th to 14th centuries (see

Moriya, 1981).

3. Kata is described in the New Kabuki Encyclopedia as follows: “Kata essentially are fixed

forms or patterns of performance and, while the term most commonly refers to acting,

may be found in all production elements, such as the arrangement of a program, of

scenes, and the traditions of scenery, props, wigs, makeup, music, and costumes.[...] A

kata may be said to have been born when an actor created an appropriate interpretation

of the spirit of a play and his role in it (in terms of movement, speech, appearance, and

so on) and this interpretation was transmitted as a convention to the next generation of

actors...” (Leiter, 289)

However, in my opinion, kata in Kabuki is more a pattern, while kata in Noh is

more form, or Form in the sense close to the Platonic idea. Kata as pattern can be changed,

as we see in the history of Kabuki, but kata of Form cannot, since Noh will no longer be

Noh if its kata is changed (See Mori, 1997, II).

4 Bert O. States holds a similar view of character: “All characters in a play are nested

together in ‘dynamical communion,’ or in what we might call a reciprocating balance of

nature: every character ‘contains in itself’ the cause of actions or determinations, in

other characters and the effects of their causality… Hamlet is made of Gertrude and

Claudius, Osric and Horatio, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, et cetera and vice versa.

Seen from the characterological viewpoint, Hamlet is a collection of relationships”(146-

48).

5. A Kabuki critic and scholar, Tamotsu Watanabe, claims that the koh-joh scene presents

the essence of Kabuki in various aspects (see Watanabe, 1989).

6. The intersection of reality and ficitionality is most clearly seen in the convention of

Kabuki’s onnagata, a female impersonator. As is well known, this convention was

practiced in Elizabethan theater, too. But the comparison of both cases would show the

differences of theatrical sensibility between the East and the West. To take examples

from Shakespearean comedies, Viola and Rosalind disguised as men do not conceal

their true selves from the audience, and the audience knows everything and enjoys the

various layers of philosophical implications in their ironic situations. In contrast, Kabuki’s

disguise hides the true self of the character not only from other characters in the play

but also from the audience, so that the revelation of the real self is a surprise for both. A

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

92 Mitsuya Mori

typical example is the Hamamatsu-ya scene in the play Benten the Thief. The thief is a

handsome young man and played by an actor who can be an onnagata. When he appears

on the stage, disguised as a young princess, the audience naturally takes him as an

onnagata—that is, a genuine princess who is not disguised. He even uses some theatrical

gimmicks to maintain that illusion with the audience. It is in the climactic scene that he

is detected as a man. He suddenly takes off his kimono and identifies himself with a

long and melodiously narrated monologue.

7. This characteristic of theatricality in theater will become clear when we consider cinema.

Cinema has, on the surface, a similar structural relationship between actor, character

and audience. In a movie house an audience is watching an actor playing a character,

but on the screen. The essential difference between theater and cinema is often expressed

by the phrase, “the theater audience confronts a real person on the stage while the

cinema audience watches only a shadow of a person on the screen.” Structurally speaking,

this means that cinema is based solely on the conceptual relationship of (b), not at all on

the physical one of (a), though this may sound the other way round at first. A movie

actor looks just like himself on the screen, that is, the same as in his actual life. But this

is so because there is no gap between Actor and Player. If what we are watching must be

either a real person or a fictional character, it must be a character, for otherwise we

could not enjoy the fictional world there. When we see Laurence Olivier playing Hamlet

on the stage, we never imagine that Hamlet actually looks like Olivier. But when he is

playing Hamlet on the screen, Hamlet is no one but he. This is another way of saying

that cinema is totally realistic. Therefore, a movie, even a spectacular type, does not

give us a feeling of theatricality. Anything on the screen does not appear artificial (not

theatrical in every sense of the word) to our eyes; if it does, it must be a miserable

failure.

8. It may be difficult to imagine that Sumo wrestling was in the old days regarded as

geinoh. But it was geinoh not because it was something like today’s pro-wrestling—a

kind of show entertainment—but because it was a performing competition dedicated

to divine beings. If this sounds odd to us today, it is because we have lost the ability to

sense the transformation of Sumo elements to those of triangle (b). In contrast, the tea

ceremony gives us a clear feeling of geinoh. Here Player and Spectator easily transform

themselves to Actor and Audience. Despite the fact that no shadow of Character appears

in the performance, the feeling for a larger world clearly emerges. Actor and Audience

constantly exchange their roles during the performance, and yet the host is the host and

the guests are the guests; the triangle structure remains.

Works Cited

Brook, Peter. The Empty Space. London: MacGibbon & Kee Ltd., 1968.

Carlson, Marvin. Places of Performance: the Semiotics of Theater Architecture. Ithaca & London:

Cornell University Press, 1989.

Leiter, Samuel L. New Kabuki Encyclopedia, a Revised Adaptation of Kabuki Jiten. Westport,

Connecticut & London: Greenwood Press, 1997.

Mori, Mitsuya, “Thinking and Feeling.” In Stanca Scholz-Cionca & Samuel L. Leiter (eds),

Japanese Theater & the International Stage. Leiden, Boston & Köln: Brill, 2001.

——. “Noh, Kabuki and Western Theater: An Attempt at Schematizing Acting Styles.”

Theater Research International, Spring Supplement, Oxford University Press, 1997.

——. “Koten-geki to gendai-geki (Classical and Modern Theater).” Iwanami Koza, Kabuki,

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

A Japanese View of Theatricality 93

Bunraku, Vol.1, Tokyo: Iwanami, 1997.

Moriya, Tsuyoshi. “Introduction”, Nihon Geinoh-shi (The History of Japanese Geinoh). Vol. 1,

Tokyo: Hosei University Press, 1981.

States, Bert O. Great Reckonings in Little Rooms. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University

of California Press, 1985.

Watanabe, Tamotsu. Kabuki: kajonaru kigo no mori (Kabuki: A Forest of Signs). Tokyo: Shin-

yoku-sha, 1989.

SubStance # 98/99, Vol. 31, nos. 2 & 3, 2002

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Einstein on the Beach: The Primacy of Metaphor in Modernist PerformanceDocument13 paginiEinstein on the Beach: The Primacy of Metaphor in Modernist PerformancementalpapyrusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Made in TokyoDocument20 paginiMade in Tokyoricardo80% (5)

- Alienation Effect BrechtDocument13 paginiAlienation Effect BrechtmurderlizerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Composition For Dance in The Twenty-First CenturyDocument12 paginiMusic Composition For Dance in The Twenty-First CenturygrifonecÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Guide To The Theory of DramaDocument31 paginiA Guide To The Theory of Dramamele_tÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auslander - Performance Analysis and Popular Music A ManifestoDocument14 paginiAuslander - Performance Analysis and Popular Music A ManifestotenbrinkenÎncă nu există evaluări

- M07S1AI1Document3 paginiM07S1AI1marceloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Analysis of Theatral PerformanceDocument19 paginiThe Analysis of Theatral PerformanceDaria GontaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nou 41 SmethurstDocument11 paginiNou 41 SmethurstVictor Cantuário100% (1)

- History of Theatre AestheticsDocument19 paginiHistory of Theatre AestheticsSubiksha SundararamanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stanislavsky and MusicDocument14 paginiStanislavsky and MusicJason Liebson100% (2)

- What Is TheaterDocument4 paginiWhat Is Theaterpyramus babyloniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Music Theatre PDFDocument66 paginiWhat Is Music Theatre PDFSinan SamanlıÎncă nu există evaluări

- David Roesner "Eraritjaritjaka - and - The - Intermediality" - oDocument11 paginiDavid Roesner "Eraritjaritjaka - and - The - Intermediality" - oLjubiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Guide To The Theory of Drama by Manfred JahnDocument45 paginiA Guide To The Theory of Drama by Manfred JahnPau StrangeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kurt Weill Gestus in MusicDocument6 paginiKurt Weill Gestus in MusicAlejandro CarrilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theatre: The Essential ElementsDocument30 paginiTheatre: The Essential ElementsDianne Rose LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report in HumanitiesDocument41 paginiReport in HumanitiesHarold AsuncionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theatrical Styles EssayDocument2 paginiTheatrical Styles EssayJack BatchelorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creative Writing SLM 1 QIV (LEA)Document12 paginiCreative Writing SLM 1 QIV (LEA)Letecia AgnesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Analysis of Theatrical Performance: The State of The ArtDocument19 paginiThe Analysis of Theatrical Performance: The State of The ArtYvonne KayÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Function of the Tragic Greek Chorus: Examining the Role and PurposeDocument9 paginiThe Function of the Tragic Greek Chorus: Examining the Role and PurposeKaterina SpanouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improvisation - Oxford Reference PDFDocument22 paginiImprovisation - Oxford Reference PDFSveta NovikovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emptiness of This Stage Signifies NDocument12 paginiThe Emptiness of This Stage Signifies NRastislav CopicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluating TheaterDocument8 paginiEvaluating TheaterCHRISTINE MERTOLAÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Distantation-Effect". More Accurately It Is "The Effect That Makes Things Seem Strange orDocument2 pagini"Distantation-Effect". More Accurately It Is "The Effect That Makes Things Seem Strange orjazib1200Încă nu există evaluări

- Here and Now Again and Again Re PerformaDocument13 paginiHere and Now Again and Again Re PerformaGianna Marie AyoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aesthetics Final PaperDocument11 paginiAesthetics Final Paperapi-253279860Încă nu există evaluări

- Theatrical Dance - How Do We Know It When We See It If We Can't Define ItDocument12 paginiTheatrical Dance - How Do We Know It When We See It If We Can't Define It蔡岳泰Încă nu există evaluări

- A Guide To The Theory of DramaDocument43 paginiA Guide To The Theory of DramaKim MustakimÎncă nu există evaluări

- One Act PlayDocument1 paginăOne Act PlayErlGeordieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theatrical Mise-En-Scene in Film FormDocument8 paginiTheatrical Mise-En-Scene in Film FormAna MarquesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dramatic Text Structure and FunctionsDocument10 paginiDramatic Text Structure and FunctionsPalabras VanasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to DramaDocument30 paginiIntroduction to DramaGulalai JanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nicholas Cook (Editor), Richard Pettengill (Editor) - Taking It To The Bridge - Music As Performance-University of Michigan Press (2013) - 87-102Document16 paginiNicholas Cook (Editor), Richard Pettengill (Editor) - Taking It To The Bridge - Music As Performance-University of Michigan Press (2013) - 87-102EmmyAltavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Nature of Dramaturgy: Describing Actions at Work: Eugenio BarbaDocument4 paginiThe Nature of Dramaturgy: Describing Actions at Work: Eugenio BarbaJosephine NunezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auslander 2006 Musical PersonaeDocument21 paginiAuslander 2006 Musical PersonaeMarta García QuiñonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art DefinitionDocument16 paginiArt DefinitionShiena Mae Delgado RacazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anna Kurpiel - Kabuki EssayDocument7 paginiAnna Kurpiel - Kabuki Essayapi-210425152Încă nu există evaluări

- David Bordwell on the Musical Analogy in Film TheoryDocument16 paginiDavid Bordwell on the Musical Analogy in Film TheoryMario PMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kanno - 2012 - As If The Composer Is DeadDocument13 paginiKanno - 2012 - As If The Composer Is DeadCristián AlvearÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seeing the Voice, Hearing the Body: The Evolution of Music TheaterDocument10 paginiSeeing the Voice, Hearing the Body: The Evolution of Music TheaterThays W. OliveiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements of Musical TheatreDocument12 paginiElements of Musical TheatreKrystal Alcanar100% (2)

- Drama in LiteratureDocument8 paginiDrama in LiteratureChikiarifuka OzaleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dramaturgy and Playwriting in The TheatrDocument16 paginiDramaturgy and Playwriting in The TheatrPhillippe Salvador PalmosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Art of Walking and Stillness: The Essential Elements of Traditional Japanese Noh Theatre and Its Influence On Method ActingDocument6 paginiThe Art of Walking and Stillness: The Essential Elements of Traditional Japanese Noh Theatre and Its Influence On Method ActingDiana Cretu100% (1)

- The Process of Evaluating PerformancesDocument2 paginiThe Process of Evaluating PerformancesMisterMolloyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 4 Use of PlaysDocument33 paginiWeek 4 Use of Playsemirtas0411Încă nu există evaluări

- Basic Elements of ActingDocument29 paginiBasic Elements of ActingJomel Bermundo100% (3)

- Music, Gesture and the Embodiment of the Utopian ImaginationDocument42 paginiMusic, Gesture and the Embodiment of the Utopian ImaginationNanda AndradeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origin-of-DramaDocument4 paginiOrigin-of-Dramasachied1023Încă nu există evaluări

- Mind in Art Author(s) : Jōji Yuasa Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), Pp. 178-185 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 09/12/2010 05:21Document9 paginiMind in Art Author(s) : Jōji Yuasa Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), Pp. 178-185 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 09/12/2010 05:21Siraseth Pantura-umpornÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capítulo 11. Poderes Virtuales. Langer - Susanne - K - Feeling - and - Form - A - Theory - of - Art-183-201 PDFDocument19 paginiCapítulo 11. Poderes Virtuales. Langer - Susanne - K - Feeling - and - Form - A - Theory - of - Art-183-201 PDFMtra. Alma Gabriela Aguilar RosalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument30 pagini06 - Chapter 1 PDFPIYUSH KUMARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance ArtDocument1 paginăPerformance ArtDiane CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eco, U. (1989) The Poetics of The Open Work PDFDocument11 paginiEco, U. (1989) The Poetics of The Open Work PDFpaologranataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acting and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated ChecklistDocument12 paginiActing and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated Checklistvictorz8200Încă nu există evaluări

- TheaterDocument2 paginiTheaterJose Emmanuel LutraniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PlaywrightDocument4 paginiPlaywrightGiorgio MattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismDe la EverandThe Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Music for the Stage: A Practical Guide for TheatremakersDe la EverandWriting Music for the Stage: A Practical Guide for TheatremakersEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Master-LK CompressedDocument33 paginiMaster-LK CompressedTú HoàngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esther and The King Color by NumberDocument2 paginiEsther and The King Color by Numbermarilyn micosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detailed Estimate of A G-3 Building in Excel - Part 11 - Headroom & Lift Slab PDFDocument1 paginăDetailed Estimate of A G-3 Building in Excel - Part 11 - Headroom & Lift Slab PDFmintu PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quincy Selected PaintingsDocument56 paginiQuincy Selected PaintingsManuel Miranda-parreño100% (1)

- Boq - of Renovation Works For - Crystal Technology BD LTDDocument16 paginiBoq - of Renovation Works For - Crystal Technology BD LTDAnower ShahadatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protective Coating System ISO-12944-5 Pinturas TIKURILLADocument2 paginiProtective Coating System ISO-12944-5 Pinturas TIKURILLAmiguel0581Încă nu există evaluări

- 101 Original One-Minute Monologues-AltermanDocument129 pagini101 Original One-Minute Monologues-AltermansofiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music MKMNNMBJBJN BNBDocument33 paginiMusic MKMNNMBJBJN BNBVignesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To PowerPoint 2016Document6 paginiIntroduction To PowerPoint 2016Vanathi PriyadharshiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aw1 Progress Test Unit 2Document4 paginiAw1 Progress Test Unit 2andres hinestrosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Destroy This Mad Brute Vs VogueDocument2 paginiDestroy This Mad Brute Vs VogueMia CasasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stylistic Analysis of The Poem 'Daffodils': A Lingua - Cognitive ApproachDocument8 paginiStylistic Analysis of The Poem 'Daffodils': A Lingua - Cognitive ApproachjalalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Odc Gym Schedule 2010 FinalDocument1 paginăOdc Gym Schedule 2010 FinalmaesaxtonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DecoArt 2019 ProductCatalog PDFDocument108 paginiDecoArt 2019 ProductCatalog PDFelizaherrera1Încă nu există evaluări

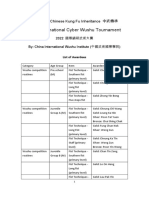

- List of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentDocument11 paginiList of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentMOUSTAFA KHEDRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dancing Steps PDFDocument18 paginiDancing Steps PDFVlad VladÎncă nu există evaluări

- KusamakuraDocument3 paginiKusamakuraMeggy Villanueva0% (1)

- Week6 SingleStickDocument6 paginiWeek6 SingleStickjkd01Încă nu există evaluări

- Seerveld CreativityDocument5 paginiSeerveld CreativityAnonymous cgvO8Q00FÎncă nu există evaluări

- Astoria Grand Brochure PlansDocument12 paginiAstoria Grand Brochure PlansindyanexpressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spme IIIDocument202 paginiSpme IIIYogesh SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engl Anleitung fc3bcr Mama Lemur 1Document8 paginiEngl Anleitung fc3bcr Mama Lemur 1Itzel LazcanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test - Past Simple - To BeDocument2 paginiTest - Past Simple - To BeMadalina CristeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animated Life - Floyd NormanDocument289 paginiAnimated Life - Floyd NormancontatoanakasburgÎncă nu există evaluări

- October 2010 CatalogDocument32 paginiOctober 2010 CatalogstampendousÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Encounter With Arts Why?Document2 paginiMy Encounter With Arts Why?JohnPaul Vincent Harry OliverosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reper To RioDocument6 paginiReper To RioRoger de TarsoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mastering: Classical RealismDocument6 paginiMastering: Classical RealismBilel Belhadj RomdhanÎncă nu există evaluări