Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Managing Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: Psychiatry

Încărcat de

1234chocoTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Managing Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: Psychiatry

Încărcat de

1234chocoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Psychiatry CLINICAL PRACTICE

Managing mental illness

in patients from CALD

backgrounds

Litza A Kiropoulos, BEd-Sc, BSc (Hons) Psych, MClinPsych, PhD (Psych), is a Research Fellow,

Department of General Practice, Monash University, Victoria. litza.kiropoulos@med.monash.edu.au

Grant Blashki, MD, FRACGP, is Senior Research Fellow, Department of General Practice, Monash University, Victoria,

and Honorary Senior Lecturer, Health Services Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College London.

Steven Klimidis, BSc (Hons) Psych, PhD (ClinPsych), is Associate Professor and Research Co-ordinator, Centre for

International Mental Health, University of Melbourne and Victorian Transcultural Psychiatry Unit, Victoria.

BACKGROUND

Australian general practitioners are often the first point of call for people seeking

mental health care including those from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD)

backgrounds, some of whom may be more at risk of having a mental illness but are

failing to access the appropriate mental health care.

OBJECTIVE

This article is intended to assist GPs in the recognition, diagnosis and management

of mental illness in patients from CALD backgrounds by providing current research

evidence and presenting some practical recommendations. More attention is paid to the

larger CALD populations such as the southern European and Asian communities, and

does not deal with indigenous Australians.

DISCUSSION

There is an increasing call for GPs to have a key role in the detection, diagnosis and

management of mental illness, including for patients from CALD backgrounds. Effective

care requires that GPs are aware of, and understand how culture may influence

recognition, diagnosis and management of mental illness in this group of patients.

significant proportion of Australias

population consists of people from culturally

and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds.

According to the Australian 2001 Census,

28% of the Australian population were born

overseas; 15% in a non-English speaking

country (Table 1). 1 Notably, older persons

from CALD are becoming a substantial

subgroup among the Australian population;

by 2026 it is projected that one in four

people aged 70 years and over will be from

a CALD background.2 These figures will have

significant implications for general practice

as general practitioners are often the first

point of contact for people requiring mental

health care. However, even though census

data has indicated that 15% of the Australian

population is from a CALD background, only

7% of encounters with GPs were recorded

for CALD people in a national survey of GP-

patient encounters. 3 These consultations

were less likely to involve a psychological

or social problem than patients from an

English speaking background.3 Research also

suggests that people from CALD backgrounds

often prefer to consult with GPs who are of

the same ethnic background or who speak

the same primary language as themselves.4

Research regarding differences in rates of

mental illness in CALD populations compared

with their Australian born counterparts has

been equivocal. The National Health and

Wellbeing Survey found little difference

in rates of affective and anxiety disorders

between people from CALD backgrounds

and Anglo-Australians 5 (although the study

excluded those who could not speak English

sufficiently well to complete the interviews).

However, more recent Australian studies

employing culturally sensitive research

methodology (ie. interview in participant's

own language) have shown that people from

CALD backgrounds have higher levels of

depression and anxiety than their AngloAustralian counterparts. 4,6 The discrepancy

between the low level of GP consultations

involving social and psychological problems

found in CALD populations, and higher

rates of mental illness noted in some

Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 34, No. 4, April 2005 4 259

Clinical practice: Managing mental illness in patients from CALD backgrounds

CALD populations, have been attributed

to a number of factors related to the

presentation of illness by the patient and

the underdetection, misdiagnosis and

management of mental illness by GPs.

What is culture?

Culture has been defined as a shared

learned behavior transmitted from one

generation to another for purposes of

individual and societal growth, adjustment

and adaptation.7 It is represented externally

as artefacts, roles, and institutions, and

internally as values, beliefs, attitudes and

biological functioning. 7 The term 'culture'

also refers to the shared heritage and social

distinctiveness of the multiplicity of the

ethnic components within a community.

However, it is important to note that it is

impossible to generalise characteristics of

a particular culture to all members of that

group, as not all members subscribe to the

values, beliefs or behaviours common to that

group and members have different levels of

acculturation to mainstream culture.8

Presentation, detection and

diagnosis of mental illness

The influence of culture

Mental illness in different cultures constitutes

different forms of social reality 9 and

needs to be understood within the cultural

context. Cultural factors shape mental illness

including how it is understood and explained,

its experience and manifestation, and its

course and epidemiology.10,11 Some factors

influenced by culture affecting the GP-patient

interaction include: somatisation, explanatory

models, perception of the GP by the

patient, the patients social context, stigma

associated with mental illness, language

difficulties, the GP setting, the role of family

and other social networks and expectations

of medication and religious beliefs.

Somatisation

Cultural variations have been noted in the

expression and presentation of mental

illness in general practice.12 Patients from

some CALD backgrounds who have a mental

illness may present more often to their

GP with somatic rather than psychological

symptoms. 1315 This has been termed

somatisation and can be understood as

a culturally appropriate way of expressing

discomfort in many cultures. 13,16,17 For

example, CALD patients might complain to a

GP of somatic symptoms such as insomnia,

headaches, lethargy, abdominal, muscular,

back and joint pains, rather than low mood

or negative thoughts.15,18

Explanatory models

Detection of mental illness in general

p r a c t i c e c a n b e i n f l u e n c e d by t h e

patients conceptualisation of the illness

experience or their explanatory model.19 An

explanatory model relates to the meaning

of illness, specifically, what constitutes

the views of causes, important symptoms,

course, consequences, and treatments or

remedies.20 All aspects of the explanatory

model are influenced and shaped by culture

and social factors such as socioeconomic

status and education, 21 and can influence

help seeking, compliance with treatment

and patient satisfaction.22

Cultural variation in explanatory models is

particularly relevant to causal attributions of

mental illness. For example, psychosomatic

causation is widely accepted by southern

Europeans for anxiety or depression. 23

Indeed, in much of Italian and Greek culture

nerves or nervous breakdowns are not

highly stigmatised but are viewed instead as

common, often minor, afflictions.23 The typical

treatment of nerves may include prayer,

efforts to adopt a better attitude or seek a

change in the social or physical environment.23

Additionally, causal beliefs about mental

illness in older people of southern European

cultures have included witchcraft, demonic

forces and supernatural explanations,

especially in females of low socioeconomic

status and low educational levels, and those

that migrated from rural areas.24 Therefore,

GP consultations with patients from CALD

backgrounds may require a negotiation of

explanatory models where differences in

belief systems are acknowledged and

260 3Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 34, No. 4, April 2005

Table 1. Australian 2001 census data:

birthplace by country for NESB*

Country

% NESB

population

Italy

1.15

Vietnam

0.82

China

0.70

Greece

0.61

Germany

0.57

Philippines

0.55

India

0.50

Netherlands

0.44

Malaysia

0.41

Lebanon

0.38

Poland

0.30

Yugoslavia

0.29

Sri Lanka

0.28

Croatia

0.27

Indonesia

0.25

Malta

0.24

Fiji

0.23

FYROM**

0.23

Republic of South Korea

0.20

Singapore

0.18

Egypt

0.17

Turkey

0.16

France

0.09

Born elsewhere overseas*** 3.70

* non-English speaking background

** Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

*** born elsewhere overseas (includes

inadequately described, at sea, not elsewhere

classified)

respected. Questions around the patients

view of mental illness will elicit information

about their explanatory model. Table 2

provides questions that can be used by GPs

to elicit CALD patients explanatory models

based on Kleinmans20 original concepts of

health and sickness and the Short Explanatory

Model Interview (SEMI).25

Perception of the GP

Patients from CALD backgrounds may have

different expectations, concerns, meanings

and values about GPs, and may view the GP as

the expert on physical illness. They may think

their role as patient is to present and describe

their physical illness; in part this may explain

the high rate of somatic presentations to GPs.

Clinical practice: Managing mental illness in patients from CALD backgrounds

It may also explain why emotional, social and

psychological difficulties are less often reported

to a GP, as the problem may not be considered

relevant or appropriate to report to a GP.20,26

Some studies suggest that different

communication styles in patients from

CALD backgrounds may be characterised

by a less direct and assertive manner. 27

This may explain why patients sometimes

readily agree with the treatment plan (in

order to please the physician) but do not

comply. Other studies suggest that patients

from CALD backgrounds may expect a

more authoritarian GP in the patient-doctor

relationship, often resulting in passive

acceptance of treatment and low demand

for education about medication.28

Patients social context

Mental illness may be strongly influenced

by adverse social circumstances and may

alert the GP to the possibility of a mental

illness.29,30 For example, factors affecting the

clinical presentation may include the political

context of arrival, reasons for migration (eg.

refugee, economic), level of contact with the

Table 2. Eliciting explanatory models of illness in CALD patients

Nature and causes of the problem

When did you first notice that there was a problem?

Why do you think that the problem began when it did?

What do you call this problem? What is its name?

How long ago did you first notice these problems?

What do you think caused this problem?

Do you think that this problem is an illness?

Australian majority group, level of exposure to

high risk industries, and lower postmigration

employment status relative to education.

Recent adverse life events (>1 in the past

year) could be seen as a reliable indicator of

mental illness in CALD patients, in addition

to multiple visits to the GP (>10 visits per

year). Therefore, those patients from CALD

backgrounds who have had recent adverse

life events or who attend the GP frequently,

warrant particular attention regarding their

psychological wellbeing.

Patients from CALD backgrounds are also

more likely to present to the GP at a later stage

of their mental illness, tolerating a great deal

of emotional and psychological distress before

seeking professional assistance.13 Patients may

consult a GP after having consulted a number

of other culturally appropriate healers, or may

be using other culturally sanctioned remedies

and rituals for their mental health.13

Stigma

Important symptoms of the problem

What do you think are the most troublesome aspects of this problem?

Which symptoms trouble you most?

Development and course of problem

How did the problem develop with time up to now?

How do you think this problem may develop and progress over time in the future?

Do you think the condition would become worse, improve or stay the same, or come

and go over time?

Severity and consequences of the problem

How serious do you think this problem is?

What are the most and least troublesome aspects of the problem?

What are the main difficulties your problem has caused you? How does the problem

affect your relationships, work/study, family role and responsibilities, attending to

your daily needs?

Treatment and help seeking for problem

Is there a particular way that people in your culture/ethnic group deal with this type

of problem? What is usually done?

Is this relevant to do in your case?

What do you think will be effective to help with this problem in your case?

What do you think you can do to help with this problem?

How do you think I can help with this problem?

(If medicine is asked for) Do you think the medicine will cure the problem or just help

control it? How quickly do you expect the medicine to do this?

The stigma associated with having a mental

illness may be particularly strong in some

CALD populations and this affects symptom

disclosure and help seeking behaviour. This may

be one of the explanations for presentation with

somatic symptoms as these may be viewed

as more socially benign than a psychological

problem.31,32 Depressive symptoms may be

seen as socially disadvantageous, and in some

cultures may interfere with marriage prospects,

diminish social status, and compromise the

self esteem required to perform effectively in

society.31,32

Language difficulties

Language preferences affect selection of GPs

by people from CALD backgrounds with

recent surveys showing that 39.5% of nonEnglish speaking patient consultations were

where the GP consulted in a language other

than English,3 and 78% of CALD patients

with poor English proficiency attended

bilingual GPs.4 For nonbilingual GPs, a trained

interpreter should be used to ensure a

meaning orientated translation. Interpreters

are available through the Translating and

Interpreting Service (www.immi.gov.au/tis/) or

Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 34, No. 4, April 2005 4 261

Clinical practice: Managing mental illness in patients from CALD backgrounds

VITS (www.vits.com.au/services/interpreting.

htm). Using an interpreter will help avoid

mistranslations of biomedical concepts and

errors of omission. An interpreter is preferred

over a family member as the patient may

not want to disclose information in front of

family and/or the family member may add

their own interpretations.

General practice setting

Underdetection of mental illness in general

practice is a complex issue that may be

exacerbated by difficulties in eliciting a

psychiatric history from CALD patients.33 For

example, GPs have been shown to diagnose

CALD patients using more limited indicators of

depression (ie. depressed appearance, sleep

disturbance, weight and appetite changes)

and are more likely to detect more severe

mental illness in general practice.33 Therefore

GPs need to be alert to the early signs of

emotional difficulties in CALD patients.

Role of family and friends

In many cultures, family members and close

friends play a key role in the patients health

care and often accompany the patient,

especially if they have limited English skills.

The GP needs to make sure that the patient

has explicitly given permission for any

discussions that might violate the patients

confidentiality. Where strong collectivistic

values typify the culture, the GP should be

aware that they may be negotiating treatment

with the entire family even if they are not

present. Acknowledging the importance of

other family members and accommodating

their views of the treatment is often essential

to adherence to the treatment plan.

Pharmacological management

N o n c o m p l i a n c e w i t h p s y ch o t r o p i c

medications appears to be more problematic

and prevalent in some nonwestern

cultures. 34 In recent years, research has

found significant differences among ethnic

groups in their response and propensity

to side effects of medications related to

genotypic variations in drug metabolising

isoenzymes. 3537 These differences lead to

variability in pharmacokinetics (ie. absorption,

distribution, metabolism and excretion) and

pharmacodynamics (ie. drug response to

psychotropic agents).38 Metabolism is regarded

as the most significant factor in determining

inter-individual and inter-ethnic differences.39,40

While a detailed description of these

differences is beyond the scope of this article,

GPs should consider variable metabolism

between ethnic groups before prescribing

psychotropics such as antidepressants,

benzodiazepines or antipsychotic medications.

Expectations of medications

Expectations of drug effects are strongly

influenced by a patients cultural origin. For

example, in some studies, patients from a

CALD background are more likely to have

negative attitudes toward medications and to

have poorer medication adherence.34 In some

studies, Chinese patients commonly perceived

that western medicines were more potent and

had greater adverse side effects than herbal

or traditional therapies.41 In another study

examining the side effects of lithium in Chinese

patients, although the actual side effect profile

was similar to caucasians, Chinese patients

showed more concern about fatigue and

drowsiness and were less concerned about

polydipsia and polyuria as such side effects

were regarded as a way of removing toxins

from the body.28 A further study found that

even though Chinese patients expected

western medicines to act quickly, they did not

expect them to treat the underlying condition.42

Religious beliefs

Religious beliefs may also affect compliance

with medication in people from CALD

backgrounds. For example, changes in intake

time and dosing of medication by some Muslim

patients during Ramadan have been found,

often without seeking GP advice.43 As efficacy

and toxicity of psychotropic medications can

vary depending on the time of administration

and their interaction with food intake, GPs

must consider religious beliefs when advising

patients. This is even more relevant for drugs

with a narrow therapeutic index as the risk of

toxicity or side effects are higher.43

262 3Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 34, No. 4, April 2005

Referral

General practitioners are the most common

referral source to specialist mental health

services for people experiencing a mental

illness and studies suggest that people from

CALD backgrounds are accessing specialist

mental health services at a lower rate compared

to the Australian born population.4 General

practitioners should familiarise themselves with

bilingual mental health professionals and ethnospecific services where they can refer CALD

patients or receive specific advice regarding

assessment and treatment.

Conclusion

General practitioners play a key role in the

detection, diagnosis and management of

CALD patients with mental illness, although

more research is clearly needed. Effective

care requires understanding and awareness

of how culture may affect the patient, GP, and

setting factors. The complex task of managing

mental illness in CALD populations can be

made easier by better understanding of the

patients culture, social and family context,

their explanatory models, their perception of

the GP, and the stigma associated with mental

illness. Additionally, GPs need to be aware of

factors contributing to the variable metabolism

of medications across CALD groups.

Summary of important points

Negotiate explanatory models with

your patient.

Be aware of the stigma that mental

illness may carry in some cultures.

Use interpreters to facilitate the GPpatient interaction.

Involvement of family and friends may

facilitate the GP-patient consultation

and treatment compliance.

Pharmacological effects may differ in

patients from CALD backgrounds.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1.

2.

National Census of Population and Housing Data 2001.

Basic community profile, Australia. Canberra: Australian

Bureau of Statistics, 2001. (ABS Catalogue No. 2001.0).

Gibson D, Braun P, Benham C, Mason F. Projections of

older immigrants: people from culturally and linguistically

diverse backgrounds, 19962026. Canberra: Australian

Clinical practice: Managing mental illness in patients from CALD backgrounds

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

Institute of Health and Welfare, 2001.

Knox SA, Britt H. A comparison of general practice

encounters with patients from English speaking and

non-English speaking backgrounds. Med J Aust

2002;177:98101.

Stuart GW, Klimidis S, Minas IH. The treated prevalence of mental disorder amongst immigrants and the

Australian born: community and primary care rates. Int J

Soc Psychiatry 1998;44:2234.

McLennan W. Mental health and wellbeing: profile of

adults, Australia, 1997. Canberra: Australian Bureau of

Statistics, 1998. (ABS Catalogue No: 4326.0).

Kiropoulos LA, Klimidis S, Minas IH. Depression and

anxiety: a comparison of older aged Greek born immigrants and Anglo Australians in Melbourne. Aust NZ J

Psychiatry 2004;38:71424.

Marsella AJ. Cross-cultural research on severe mental

disorders: issues and findings. Acta Psychiatr Scand

1988;78:722.

Rosenthal D, Ranieri N, Klimidis S. Vietnamese adolescents in Australia: relationships between perceptions of

self and parental values, intergenerational conflict, and

gender dissatisfaction. Int J Psychology 1996;31:8191.

Good B, Kleinman A. Culture and depression: studies in

the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect

and disorder. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1985.

Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: implications for diagnosis

and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:228.

Marsella AJ, Kaplan A, Suarez E. Cultural considerations

for understanding, assessing and treating depressive experience and disorder. In: Reinecke MA, Davison MR,

editors. Comparative treatments of depression. New York,

NY: Springer, 2000.

Bhui K, Bhugra D, Goldberg D. Causal explanations of

distress and general practitioners assessments of common

mental disorders among Punjabi and English attendees.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2002;37:3845.

Chan B, Parker G. Some recommendations to assess

depression in Chinese people in Australasia. Aust NZ J

Psychiatry 2004;38:1417.

Gater R, De Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, et al.

The pathways to psychiatric care: a cross-cultural study.

Psychol Med 1991;21:76174.

Husain N, Creed F, Tomenson B. Adverse social circumstances and depression in people of Pakistani origin in the

UK. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:4348.

Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP.

Somatisation in cross-cultural perspective: a world health

organisation study in primary care. Am J Psychiatry

1997;154:98995.

Comino EJ, Silove D, Manicavasagar V, Harris E, Harris

MF. Agreement in symptoms of anxiety and depression

between patients and the GPs: the influence of ethnicity.

Fam Pract 2001;18:717.

Phan T, Silove D. The influence of culture on psychiatric assessment: the Vietnamese refugee. Psychiatr Serv

1997;48:8690.

Bhui K, Bhugra D. Explanatory models for mental distress: implications for clinical practice and research. Br J

Psychiatry 2002;181:67.

Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

Carillo JEA, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

primary care: a patient based approach. Ann Intern Med

1999;30:82934.

Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Lloyd KR. Common mental disorders, explanatory models and consultation behaviour

among Indian women living in the UK. J R Soc Med

1998;91:6671.

Kirmayer LJ, Young A, Robbins JM. Symptom attribution

in cultural perspective. Can J Psychiatry 1994;39:58495.

Meiser B, Gurr R. Non-English speaking persons perceptions of mental illness and associated needs: an explanatory

study of Arabic-, Greek- and Italian-speaking communities in New South Wales. Health Promotion Journal of

Australia 1996;6:449.

Lloyd KR, Jacob KS, Patel V, St Louis L, Bhugra D,

Mann AH. The development of the Short Explanatory

Model Interview (SEMI) and its use among primary care

attenders with common mental disorders. Psychol Med

1998;28:12317.

Parker G, Gladstone G, Chee KT. Depression in the

planets largest ethnic group: the Chinese. Am J Psychiatry

2001;158:85764.

Gao G, Ting-Toomey S, Gudykunst WB. Chinese

communication processes. In: Bond MH, editor. The

handbook of Chinese psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford

University Press, 1996;28093.

Lee S. Side effects of chronic lithium therapy in Hong

Kong Chinese: an ethnopsychiatric perspective. Cult Med

Psychiatry 1993;17:30120.

Odell SM, Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Commander

MJ, Sashidharan SP. Determinants of general practitioner

recognition of psychological problems on a multi-ethnic

inner-city health district. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:537

41.

Maginn S, Boardman AP, Craig TKJ, Hadad M, Heath

G, Stott J. The detection of psychological problems by

general practitioners: influence of ethnicity and other

demographic variables. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

2004;39:46471.

Bakshi L, Rooney R, ONeill K. Working transculturally

to reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness amongst

non-English speaking background communities: a guide.

Melbourne: Australian Transcultural Mental Health

Network, 1999.

Raguram R, Weiss MG, Channabasavanna SM, Devins

GM. Stigma, depression and somatization in South India.

Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:10439.

Mihalopoulos C, Pirkis J, Naccarella L, Dunt D. The role

of general practitioners and other primary care agencies in

transcultural mental health care. Melbourne: Australian

Transcultural Mental Health Network, 1999.

Li KM, Poland RE, Nakasaki G. Psychopharmacology

and psychobiology of ethnicity. Washington, DC:

American Psychiatric Press, 1993.

Ng C-H, Schweitzer I, Norman T, Easteal S. The emerging role of pharmacogenetics: implications for clinical

psychiatry. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2004;38:4839.

Matthews HW. Racial, ethnic and gender differences

in response to medicines. Drug Metabol Drug Interact

1995;12:7791.

Pi EH, Gray GE. A cross-cultural perspective on psychopharmacology. Essential Psychopharmacol

1998;2:23359.

Lin K-M. Biological differences in depression and

anxiety across races and ethnic groups. J Clin Psychiatry

2001;62:1319.

39. Sjoqvist F, Borga O, Dahl M-L, Orme MLE.

Fundamentals of clinical pharmacology. In: Speight TM,

Holford NHG, editors. Averys Drug Treatment. 4th ed.

Auckland: Adis International, 1997;173.

40. Poolsup N, Li Wan Po A, Knight TL. Pharmacogenetics

and psychopharmacotherapy. J Clin Phar Ther

2000;25:197220.

41. Lee RP. Perceptions and uses of Chinese medicine

among the Chinese in Hong Kong. Cult Med Psychiatry

1980;4:34575.

42. Owan TC. Southeast Asian mental health: Treatment,

prevention, services, training, and research. Rockville,

MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 1985.

43. Aadil N, Houti IE, Moussamih S. Drug intake during

Ramadan. BMJ 2004;329:77882.

AFP

Correspondence

Email: afp@racgp.org.au

Reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 34, No. 4, April 2005 4 263

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mental Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and the Ageing ProcessDe la EverandMental Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and the Ageing ProcessÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0408PP TrujilloDocument15 pagini0408PP TrujillojaverianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Topics On Mental IllnessDocument6 paginiResearch Paper Topics On Mental Illnesszufehil0l0s2100% (3)

- Cultural Competency in Health PDFDocument6 paginiCultural Competency in Health PDFMikaela HomukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Aspects of The Quality of Life of Persons Suffering From SchizophreniaDocument11 paginiSocial Aspects of The Quality of Life of Persons Suffering From SchizophreniaFathur RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kleinman Culture and DepressionDocument3 paginiKleinman Culture and DepressionАлександра Курленкова100% (1)

- Outsmart Your Brain The Insider's Guide to Life-Long MemoryDe la EverandOutsmart Your Brain The Insider's Guide to Life-Long MemoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Framework for the Holistic Management of SchizophreniaDe la EverandA Framework for the Holistic Management of SchizophreniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Psychological AbnormalityDocument21 paginiUnderstanding Psychological AbnormalityTitikshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology Assessment - I - M1Document42 paginiPsychology Assessment - I - M1Brinda ChughÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Health Improvement Profile: A manual to promote physical wellbeing in people with severe mental illnessDe la EverandThe Health Improvement Profile: A manual to promote physical wellbeing in people with severe mental illnessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Mental HealthDocument5 paginiResearch Paper Mental Healthc9s9h7r7100% (1)

- Depression - Let's TalkDocument9 paginiDepression - Let's TalkThavam RatnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Living with Bipolar: A Guide to Understanding and Managing the DisorderDe la EverandLiving with Bipolar: A Guide to Understanding and Managing the DisorderEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- STUDENTS STRUGGLING WITH ANXIETY AND DEPRESSIONDocument10 paginiSTUDENTS STRUGGLING WITH ANXIETY AND DEPRESSIONAmie TabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology and Aging: PsychologistsDocument8 paginiPsychology and Aging: PsychologistsThamer SamhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECT FOR SCHIZOPHRENIADocument17 paginiECT FOR SCHIZOPHRENIAnurisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiology for Canadian Students: Principles, Methods and Critical AppraisalDe la EverandEpidemiology for Canadian Students: Principles, Methods and Critical AppraisalEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- A Short Guide To Psychiatric DiagnosisDocument4 paginiA Short Guide To Psychiatric DiagnosisNaceiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSM V Def - Pink-1Document22 paginiDSM V Def - Pink-1Aarzoo MakhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vacarolis Chapter OutlinesDocument181 paginiVacarolis Chapter Outlinesamashriqi100% (1)

- Eugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseDe la EverandEugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Health Improvement Profile: A manual to promote physical wellbeing in people with severe mental illnessDe la EverandThe Health Improvement Profile: A manual to promote physical wellbeing in people with severe mental illnessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neurodevelopmental Psychiatry - An Introduction For Medical StudentsDocument68 paginiNeurodevelopmental Psychiatry - An Introduction For Medical StudentsNiranjana MahalingamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Breaking the Silence: Shining a Light on Schizoid Personality DisorderDe la EverandBreaking the Silence: Shining a Light on Schizoid Personality DisorderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Substance Abuse Culturally Bound? Historical, Biological & Psychodiagnostic FactorsDocument19 paginiIs Substance Abuse Culturally Bound? Historical, Biological & Psychodiagnostic FactorsPriyansh JindalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affective Disorders in Cultural Context: Laurence Kirmayer, and Danielle Groleau, PHDDocument14 paginiAffective Disorders in Cultural Context: Laurence Kirmayer, and Danielle Groleau, PHDvarhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- WHO report highlights global mental health burdenDocument29 paginiWHO report highlights global mental health burdenTet Velchez100% (1)

- Corresponding Author: Joel Adeleke AfolayanDocument29 paginiCorresponding Author: Joel Adeleke AfolayanAjoy BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental health guidelines promote oral careDocument21 paginiMental health guidelines promote oral careKathrinaRodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bipolar Disorder Bipolar DisorderDocument3 paginiBipolar Disorder Bipolar DisorderJorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- How cultural diversity improves healthcare outcomesDocument5 paginiHow cultural diversity improves healthcare outcomesCindy Mae CamohoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinician's Guide to Chronic Disease Management of Long Term Conditions, TheDe la EverandClinician's Guide to Chronic Disease Management of Long Term Conditions, TheÎncă nu există evaluări

- UnconsciousnessDocument6 paginiUnconsciousnessSeema RahulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition of Disease and the Social Construction of IllnessDocument11 paginiDefinition of Disease and the Social Construction of Illnessbtailor17Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Palliative Care Principles and HistoryDocument26 paginiIntroduction to Palliative Care Principles and HistoryAbdullah SakhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental HealthDocument3 paginiMental Healthapi-293693569Încă nu există evaluări

- Download Wisdom Mind Mindfulness For Cognitively Healthy Older Adults And Those With Subjective Cognitive Decline Facilitator Guide Colette M Smart all chapterDocument68 paginiDownload Wisdom Mind Mindfulness For Cognitively Healthy Older Adults And Those With Subjective Cognitive Decline Facilitator Guide Colette M Smart all chapterjohn.eusebio964100% (11)

- Nourishing Minds: The Interplay of Eating and Mental HealthDe la EverandNourishing Minds: The Interplay of Eating and Mental HealthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who PhsycogeriatriDocument6 paginiWho PhsycogeriatriWilson WilliamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trans CulturalDocument6 paginiTrans CulturalAlyssa Santos JavierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Healing Across Cultures: Pathways to Indigenius Health EquityDe la EverandHealing Across Cultures: Pathways to Indigenius Health EquityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Papers On Depression in The ElderlyDocument7 paginiResearch Papers On Depression in The Elderlyojfhsiukg100% (1)

- Fatigue and Dysautonomia: Chronic or Persistent, What's the Difference?De la EverandFatigue and Dysautonomia: Chronic or Persistent, What's the Difference?Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample Research Paper On Mental IllnessDocument9 paginiSample Research Paper On Mental Illnessebvjkbaod100% (1)

- Counseling From Within: The Microbiome Mental Health ConnectionDe la EverandCounseling From Within: The Microbiome Mental Health ConnectionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Killer Diseases, Modern-Day Epidemics: Keys to Stopping Heart Disease, Diabetes, Cancer, and Obesity in Their TracksDe la EverandKiller Diseases, Modern-Day Epidemics: Keys to Stopping Heart Disease, Diabetes, Cancer, and Obesity in Their TracksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder in ChildrenDe la EverandOppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder in ChildrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Guide: For students, teachers, school psychologists, nurses, social workers, counselors and parents.De la EverandMental Health Guide: For students, teachers, school psychologists, nurses, social workers, counselors and parents.Încă nu există evaluări

- Saludamay Nursing JournalDocument76 paginiSaludamay Nursing JournalcrisjavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FigmentDocument4 paginiFigmentanaella delacruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1 Psychology: Mental Illness Across The LifespanDocument35 paginiUnit 1 Psychology: Mental Illness Across The Lifespanapi-116304916100% (1)

- Pokemon Theme Song 22Document4 paginiPokemon Theme Song 221234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Code Geass - StoriesDocument5 paginiCode Geass - Stories1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blue Veins Sub Theme TVBDocument4 paginiBlue Veins Sub Theme TVB1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor Talk: Communication Practice Role PlaysDocument6 paginiDoctor Talk: Communication Practice Role Plays1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fairy Tail - Main ThemeDocument3 paginiFairy Tail - Main Theme1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Osteo Infographic FinalDocument1 paginăOsteo Infographic Final1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blue BirdDocument7 paginiBlue Bird1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- QLD Rail Traim PDFDocument1 paginăQLD Rail Traim PDF1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

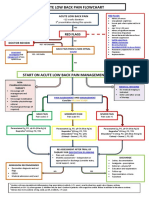

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Document1 paginăAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mbs Quick Guide: JULY 2020Document2 paginiMbs Quick Guide: JULY 20201234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First PositionDocument41 paginiGetting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First Position1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial ApproachDocument3 paginiTaking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial Approach1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- VTE GuidelinesDocument11 paginiVTE Guidelines1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDocument7 paginiTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDocument7 paginiTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- USMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideDocument190 paginiUSMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideMedSchoolStuff100% (3)

- # 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in EDDocument7 pagini# 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in ED1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PBM Module1 MTP Template 0Document2 paginiPBM Module1 MTP Template 01234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Applicant Guide Web V2Document83 pagini2016 Applicant Guide Web V21234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metro South Intern Training Form (Logan)Document3 paginiMetro South Intern Training Form (Logan)1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ImprovingMedAdherenceOlderAdultslyer Final 508CDocument2 paginiImprovingMedAdherenceOlderAdultslyer Final 508CKumar PatilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language of PreventionDocument9 paginiLanguage of Prevention1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory ArrestDocument1 paginăFLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory Arrest1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fluids ElectrolytesDocument2 paginiFluids Electrolytes1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDFDocument6 paginiHerd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDF1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defining and Assessing Risks To Health PDFDocument20 paginiDefining and Assessing Risks To Health PDF1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of HealthDocument5 paginiClinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of Health1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Conceptual Framework For HealthDocument1 paginăA Conceptual Framework For Health1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older AustraliansDocument22 paginiThe Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older Australians1234chocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Riga Participants List FINALDocument9 paginiRiga Participants List FINALFredie IsaguaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 CGMPDocument78 pagini2 CGMPRICHELLE JIELEN QUEBECÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genetic Counselling Seminar for NursesDocument22 paginiGenetic Counselling Seminar for NursesGopika SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four Handed DentistryDocument114 paginiFour Handed DentistryLie FelixÎncă nu există evaluări

- OSCE AcneDocument4 paginiOSCE AcneAliceLouisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Potency and Dose PDF SEMINARDocument62 paginiPotency and Dose PDF SEMINARMd. Mahabub Alam100% (1)

- Interpretation MRCPCH 2009 Site: For Part 2 Exam For Part 2 ExamDocument35 paginiInterpretation MRCPCH 2009 Site: For Part 2 Exam For Part 2 Examyassine100% (1)

- 3M 9105 Wear It Right Poster PDFDocument2 pagini3M 9105 Wear It Right Poster PDFScott KramerÎncă nu există evaluări

- AURELIO-Issues, Trends and Challenges On The Care of Older Persons in The Different SettingsDocument14 paginiAURELIO-Issues, Trends and Challenges On The Care of Older Persons in The Different Settings3D - AURELIO, Lyca Mae M.0% (1)

- Welcome - Embrace QuoteEngineDocument3 paginiWelcome - Embrace QuoteEnginegabyÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL - Pe11 - Q1 - Week 4Document5 paginiDLL - Pe11 - Q1 - Week 4Ysah Castillo Ü100% (1)

- A3 Process - A Pragmatic Problem-Solving Technique For Process Improvement in Health CareDocument11 paginiA3 Process - A Pragmatic Problem-Solving Technique For Process Improvement in Health CareNoé HumbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Literature on School Canteen Food QualityDocument8 paginiReview of Literature on School Canteen Food QualityRich BarriosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of HRM in improving healthcare servicesDocument8 paginiRole of HRM in improving healthcare servicesZovana 2020Încă nu există evaluări

- Provide Care and Support To People With Special NeedsDocument13 paginiProvide Care and Support To People With Special NeedsJoshua S. Ce�idozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing ProcessDocument20 paginiNursing Processwideyatma100% (2)

- Journal of Psychiatric ResearchDocument8 paginiJournal of Psychiatric ResearchMaria CamposÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBDRP-Reporting-Forms TemplateDocument21 paginiCBDRP-Reporting-Forms TemplateKarl Anne Domingo100% (1)

- Borderline Personality Disorder in Clinical Practice: Carolyn Zittel Conklin, Ph.D. Drew Westen, PH.DDocument9 paginiBorderline Personality Disorder in Clinical Practice: Carolyn Zittel Conklin, Ph.D. Drew Westen, PH.DMarjorie AlineÎncă nu există evaluări

- International General Certificate Assessor's Marking Sheet (2011 Specification) Igc3 - The Health and Safety Practical ApplicationDocument11 paginiInternational General Certificate Assessor's Marking Sheet (2011 Specification) Igc3 - The Health and Safety Practical ApplicationVigneshwaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Field Visit Gorai CemetryDocument4 paginiField Visit Gorai CemetryYogesh KharchanÎncă nu există evaluări

- NeuroDocument317 paginiNeuroNela Popa100% (2)

- Homeopathic First Aid For Infants and Children PDFDocument3 paginiHomeopathic First Aid For Infants and Children PDFRamesh Shah100% (1)

- Soal Kuis 7 Ppu - Bahasa Inggris: Text 1Document3 paginiSoal Kuis 7 Ppu - Bahasa Inggris: Text 1rayhan taufikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Air Force Body Composition Policy MemoDocument3 paginiAir Force Body Composition Policy MemoRichard PollinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of High Intensity Interval Training On Increasing Explosive Power, Speed, and AgilityDocument6 paginiEffects of High Intensity Interval Training On Increasing Explosive Power, Speed, and AgilityGytis GarbačiauskasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Achilles Tendon Injury Rehab Exercises GuideDocument6 paginiAchilles Tendon Injury Rehab Exercises GuideKEVIN NGUYENÎncă nu există evaluări

- Post-Partum Haemorrhage: Causes and Risk FactorsDocument12 paginiPost-Partum Haemorrhage: Causes and Risk FactorsLindha GraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Putnam Voice - 1/11/12Document10 paginiPutnam Voice - 1/11/12The Lima NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cloze-Exam Practice With Key (August)Document10 paginiCloze-Exam Practice With Key (August)Mar CuervaÎncă nu există evaluări