Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

W A V T ?: HAT Ffects Oter Urnout

Încărcat de

Daniel Dos Santos MaiaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

W A V T ?: HAT Ffects Oter Urnout

Încărcat de

Daniel Dos Santos MaiaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006. 9:11125

doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

c 2006 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Copyright

First published online as a Review in Advance on Dec. 12, 2005

WHAT AFFECTS VOTER TURNOUT?

Andre Blais

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

Department of Political Science, Universite de Montreal, Montreal PQ H3C 3J7,

Canada; email: andre.blais@umontreal.ca

Key Words

institutions, electoral systems, party systems, closeness

Abstract Why is turnout higher in some countries and/or in some elections than

in others? Why does it increase or decrease over time? To address these questions,

I start with the pioneer studies of Powell and Jackman and then review more recent

research. This essay seeks to establish which propositions about the causes of variations

in turnout are consistently supported by empirical evidence and which ones remain

ambiguous. I point out some enigmas and gaps in the field and suggest directions for

future research. Most of the research pertains to established democracies, but analyses

of nonestablished democracies are also included here.

INTRODUCTION

The dominant view in the literature is that the existing research on voter turnout

has established some robust patterns, that we know relatively well why turnout

is higher in some countries than in others, and that the main factors that affect

variations in turnout are institutional variables. My verdict is different. Many of

the findings in the comparative cross-national research are not robust, and when

they are, we do not have a compelling microfoundation account of the relationship.

And the impact of institutional variables may be overstated.

THE PIONEER STUDIES

The study of voter turnout started with Powells (1982) award-winning book,

Contemporary Democracies, which posited electoral participation as one of the

three main indicators of democratic performance, and two American Political

Science Review articles by Powell (1986) and Jackman (1987).

Powells APSR article examined mean turnout in 17 countries in the 1970s. He

found turnout to be higher in countries with nationally competitive districts and

strong party-group linkages. Nationally competitive districts enhance turnout

because parties and voters have equal incentive to get voters to the polls in all

parts of the country (Powell 1986, p. 21), and vote choice is simpler when and

where groups (e.g., unions, churches, professional associations) are clearly associated with specific parties (Powell 1986, p. 22). Powells main conclusion is that

1094-2939/06/0615-0111$20.00

111

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

112

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

American turnout is inhibited by its institutional context, and the main emphasis

is on party-group linkages, which is the most powerful variable in his model.

Jackmans (1987) article followed in the same spirit, with an even stronger emphasis on institutions. Jackman looks at mean turnout in 19 countries in the 1970s,

and he comes out with much cleaner results, showing that five institutional variables affect turnout: nationally competitive districts, electoral disproportionality,

multipartyism, unicameralism, and compulsory voting.

Jackman was inspired by Powells work, but the specific set of variables he retained was different. Most importantly, Powells main factor, party-group linkage,

was left out, because it was found to have no systematic effect. It was Jackmans

set of variables that defined the research agenda.

A number of comments can be made about Jackmans study. First, although

the emphasis is on institutional factors, one of themthe number of parties

should be considered as the consequence of the institutional context. Second,

two variablesnational competitive districts and electoral disproportionality

are aspects of the electoral system. They are correlated with each other (larger

districts produce more proportional outcomes), and it is not clear why the two

should be incorporated into the same model. Third, Jackmans analysis does not

include any socioeconomic variable. A fuller model should integrate the role of

the socioeconomic environment.

Powells 1982 book considers a greater array of countries, 29 in total, although

the analysis of turnout is restricted to 23 cases. His model distinguishes three blocs

of variables: the social and economic environment, the constitutional setting (institutions in the strict sense of the term), and party systems and election outcomes.

In his final path analysis model (figure 6.1, p. 121), Powell (1982) identifies four

significant variables: one socioeconomic (gross national product per capita), two

constitutional (proportional representation and mobilizing voting laws), and one

party system (party-group linkage).

Powells sequential model, which identifies a distant set of variables (socioeconomic), an intermediate set (institutions), and more proximate factors (party

systems and election outcomes), seems quite useful. I review the evidence on the

effects of these three types of factors, beginning with the impact of institutions,

which has been the focus of most research.

THE IMPACT OF INSTITUTIONS

Jackman identifies three institutions that appear to foster turnout: compulsory

voting, the electoral system, and unicameralism. Other institutional variables have

also been proposed.

Compulsory Voting

Jackman (1987) estimates that compulsory voting increases turnout by about 13

percentage points. This pattern has been confirmed by every study of turnout in

western democracies, and the magnitude of the estimated impact is almost always

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

113

around 10 to 15 points (Blais & Carty 1990; Blais & Dobrzynska 1998; Franklin

1996, 2004; Blais & Aarts 2005). Compulsory voting increases turnout can be

construed as a well-established proposition.

This raises more questions. Must compulsory voting legislation be accompanied

by sanctions in order to be efficient? What kinds of sanctions are more prone to

induce recalcitrant citizens to go to the polls? How tough must these sanctions

be? How strictly must they be enforced? The literature provides precious little to

answer these questions.

Perhaps there is more to be learned from the experience of nonestablished

democracies. Norris (2002) finds that compulsory voting increases turnout only

in older democracies, and she speculates that the law may be enforced less

strictly elsewhere or that its impact is conditional on the presence of broader norms

about the desirability of obeying the law. Fornos et al. (2004) develop a four-point

compulsory voting scale, and they report a strong impact of compulsory voting

on turnout in Latin America, the region with the highest frequency of compulsory

voting laws. They do not sort out, however, the specific contribution of sanctions

and their degree of enforcement. Finally, Blais et al. (2003) examine the effect

of compulsory voting with and without sanctions in their sample of 61 countries,

covering both established and new democracies. They find that compulsory voting

makes a difference only when there are sanctions (they do not examine the effect

of enforcement).

In summary, we know that compulsory voting increases turnout and that its

impact depends on its enforcement. But we do not know how strict that enforcement must be in order to work. We know nothing about the publics awareness

and perceptions of the law and its implementation. And there are no comparative

analyses of the determinants of turnout in countries with and without compulsory

voting. This is an unfortunate state of affairs. If a sense of duty is a crucial motivation for voting (Blais 2000), most people should be predisposed to vote, and

loosely enforced, light fines should be sufficient to produce a high turnout. And

according to rational choice, the factors that shape the decision to vote or not to

vote should be very different when there is a concrete financial cost associated with

abstention. In short we know nothing about the microfoundations of compulsory

voting (Achen 2002, but see Bilodeau & Blais 2005).

Electoral System

Jackman (1987) finds that turnout is higher in systems with nationally competitive

districts, the reason being that in large districts parties have an incentive to mobilize

everywhere while some single-member districts may be written off as hopeless.

Jackmans four-category ordinal variable takes into account the electoral formula and the size of the districts. Further research has utilized either the same

variable, or dummy variables that distinguish electoral formulas, or a summary

disproportionality index (also included by Jackman). Studies that have been confined to advanced democracies (Blais & Carty 1990, Jackman & Miller 1995,

Franklin 1996, Radcliff & Davis 2000) as well as one study of turnout in postcommunist countries (Kostadinova 2003) have confirmed that turnout is higher in

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

114

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

proportional representation (PR) and/or larger districts, whereas research dealing

with Latin America reports no association (Perez-Lina n 2001, Fornos et al. 2004),

and an analysis that incorporates both established and non-established democracies concludes that the electoral system has a weak effect (Blais & Dobrzynska

1998). See Blais & Aarts (2005) for a more detailed review of these studies.

There are two possible interpretations of the available evidence. The more

optimistic view is that PR increases turnout except perhaps in Latin America, a

region where there is some dose of proportionality in every country. The more

pessimistic view is that once one moves outside Europe there is no generalized

correlation between the electoral system and turnout. I lean toward the second,

more skeptical position. On the one hand, the study by Fornos et al. (2004) that

comes up with negative results in Latin America is at least as methodologically

sophisticated as research on established democracies. On the other hand, as I

indicate below when discussing the impact of the party system, those studies that

come up with positive results have failed to specify how and why PR fosters turnout.

Unicameralism

Jackmans (1987) last key institutional variable is unicameralism. He shows that

turnout is significantly higher in countries where power is concentrated in one

legislature. The reason is that, when there are two chambers, power is usually

shared between the two and elections for the lower house play a less decisive role

in the production of legislation where bicameralism is strong (Jackman 1987,

p. 408). The more powerful the body that is being elected, the stronger the incentive

to vote. We would expect turnout to be particularly low when and where the

legislature has little power. Jackman uses a scale [proposed by Lijphart (1984)]

with the highest score for unicameral countries and the lowest score for countries

in which the upper house is as powerful as the lower house.

Jackman focused on the division of power between the lower and upper houses,

but the same rationale should apply to the division of power between the president

and the legislature, between the central government and subnational (or supranational) governments, or between the government and the courts. The general

proposition is that the more powerful the body that is being elected, the higher the

turnout.

Surprisingly perhaps, the findings about the impact of unicameralism on turnout

are mixed. Positive results are reported by Jackman (1987), Jackman & Miller

(1995), and Fornos et al. (2004). However, Blais & Carty (1990), Black (1991),

Radcliff & Davis (2000), and Perez-Lina n (2001) indicate no effect. Siaroff &

Merer (2002) find support for the hypothesis that turnout is lower where there is a

relevant directly elected president and where there are strong regional governments. Blais & Carty (1990) and Black (1991) indicate that turnout is not higher

in federated countries. All in all, the studies that have looked at specific indicators

of the relative power of lower chambers relative to other institutions have not systematically confirmed the conventional wisdom that turnout is higher where the

lower chamber has greater leverage.

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

115

Perhaps what is needed is a summary measure of the power of national lower

houses that takes these many dimensions into account. Blais & Dobrzynska (1998)

created an electoral decisiveness scale that considers the presence or absence

of subnational elections in federations, upper house direct elections in bicameral

countries, and presidential direct elections. They find a strong positive correlation

with turnout, but their results have not been replicated.

Franklin (2004) pays close attention to parliamentary responsibility in his account of turnout change in established democracies. Franklins main concern is to

explain why turnout increases or decreases over time in different countries. His key

variable is competitiveness, which I consider below. He also argues that turnout

in legislative elections increases when parliamentary responsibility increases, and

that it decreases when parliamentary responsibility is weakened. The former is

exemplified by Malta gaining independence in the 1960s and decisions of the legislature no longer being subject to ratification by a British appointed governor.

The creation of a government cartel in Switzerland after the 1960s, which made

elections meaningless, is an illustration of the latter.

It is hard to believe that turnout is unaffected by the salience of an institution.

Yet the empirical evidence on that question is ambiguous. The challenge is to come

up with reliable scales that encompass the different dimensions of salience. The

measures used in the extant research are not very satisfactory.

Other Institutional Variables

At least two other institutional factors have been shown to affect turnout: voting

age and rules designed to facilitate voting. It is a well-established fact that the

propensity to vote increases with age (Wolfinger & Rosenstone 1980, Blais 2000),

and so we would expect turnout to be lower when the voting age is 18 instead of

21. Research that examines turnout in contemporary advanced democracies does

not incorporate that variable for the simple reason that the voting age is now 18

almost everywhere (Massicotte et al. 2004), and there is thus no variation.

Blais & Dobrzynska (1998), whose sample of elections starts in the 1970s, do

include a voting age variable and they find a relatively strong effect; their results

suggest that lowering the voting age from 21 to 18 reduces turnout by five points.

Voting age is also a key factor in Franklins (2004) study of turnout dynamics. He

estimates that the lowering of the voting age in most democracies has produced a

turnout decline of about three percentage points.

The evidence on the effect of vote-facilitating rules is more limited and ambiguous. Franklins (1996) initial analysis suggests that turnout is higher when

voting takes place on Sunday, so that people presumably have more time to go to

the polling station, and when postal (absentee) voting is available. But these same

variables proved incapable of predicting changes in turnout over time (Franklin

2004). Norris (2002) examines the effect of specific rules (number of polling days,

polling on rest day, postal voting, proxy voting, special polling booths, transfer

voting, and advance voting), and she finds no significant effect. Blais et al. (2003)

created a summary scale that reflects the presence or absence of postal, advance,

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

116

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

and proxy voting, and they find a rather strong positive association between the

presence of such voting facilities and turnout.

It makes sense to assume that people are more prone to vote if it is easy. Gimpel

& Schucknecht (2003), in particular, have shown that turnout is affected by the

accessibility of the ballot box. Likewise, there is strong evidence that allowing

voters to vote by mail increases turnout (Southwell 2004, Rallings & Thrasher

2006). The question is not whether voting facilities influence turnout but rather

which ones matter most, and how great a difference they make. In order to correctly

address these questions we need more accurate measures of these voting facilities

over time and across countries, which means that we need to know not only whether

such facilities exist but also how easy it is to use them. We also need to take into

account the endogeneity of election laws; measures to facilitate the vote may be

more likely to be adopted in countries where turnout is low or declining (Franklin

2004, p. 148). This is no easy task. For the time being, the verdict must be that we

know little about how much difference these rules make.

Conclusions

The primary focus of cross-national studies of turnout has been on the impact

of institutional variables. That impetus was shaped in good part by Jackmans

influential article. The general perception in the field (and, I must confess, my own

perception before I re-examined the evidence more closely in preparation for this

article) is that cross-national differences in turnout can be relatively well explained

by institutional variables. The perception is that we have come up with a number

of well-established propositions about how institutions influence turnout.

That perception may not be well founded. We can safely assert that compulsory

voting increases turnout, but we do not know whether a very light sanction suffices

and whether that sanction needs to be enforced. Most of the literature supports the

view that PR fosters turnout, but there is no compelling explanation of how and why,

and the pattern is ambiguous when the analysis moves beyond well-established

democracies. Many studies support the common-sense proposition that turnout

increases with the saliency of the election, but many studies report no effect. I find

it hard not to believe that turnout is higher when and where it is relatively easy to

vote, yet the empirical evidence on the effect of voting facilities is inconsistent.

All in all, our understanding of the impact of institutions on turnout is shaky.

THE SOCIOECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

We know that at the individual level the propensity to vote is associated with a number of sociodemographic characteristics, particularly age and education (Wolfinger

& Rosenstone 1980, Blais 2000). It would be natural to assume, in the same vein,

that cross-national variations in turnout are associated with socioeconomic differences between countries. Powell (1982) considers the impact of the socioeconomic

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

117

environment and finds that turnout does tend to be higher in more economically

developed countries. He also reports that turnout tends to be higher in smaller

nations, but the relationship is not statistically significant.

The most influential analyses thereafter have neglected this line of inquiry (see

especially Jackman 1987 and Franklin 1996, 2004), perhaps because they deal with

a small number of established democracies among which there is little variance in

the level of economic development. There is, however, relatively strong support for

the hypothesis that turnout is higher in economically advanced countries (Blais &

Dobrzynska 1998, Norris 2002, Fornos et al. 2004). The relationship is not linear,

the main difference being between the poorest countries and all others (Blais &

Dobrzynska 1998).

This raises the question of whether turnout increases or decreases with downturns in the economy. As Radcliff (1992) points out, both effects are possible;

economic hardship may induce people to mobilize to redress grievances, but it

may also lead them to withdraw entirely from the political process. Given these

two contradictory possibilities, the most likely outcome is a nil overall effect,

and this is precisely what most studies report (Arcelus & Meltzer 1975, Blais &

Dobrzynska 1998, Blais 2000, Kostadinova 2003, Fornos et al. 2004; for an

exception see Rosenstone 1982).

Radcliff (1992) argues that economic downturns increase turnout at high and

low levels of welfare spending but depress it at intermediate levels. However,

some of the findings are perplexing (Blais 2000, p. 34), and they have failed to be

replicated (Jackman & Miller 1995, Appendix B, note 3). The conclusion must be

that there is no clear relationship between the economic conjuncture and turnout.

In my own research, I have been struck by the fact that the highest levels of

turnout are reported in small countries such as Malta (Blais & Carty 1990. Blais &

Dobrzynska 1998). The real difference is between very small countries and all others, and the pattern is less clear at the subnational level (see Blais 2000, p. 59). The

same pattern has been observed at the local level (Oliver 2000). I have speculated

that this might result from stronger social networks in smaller communities, but that

hypothesis is inconsistent with the absence of a correlation between turnout and

urbanization [see Siaroff & Merer 2002, Fornos et al. 2004; Kostadinova (2003)

reports a negative correlation but it is quite weak]. Another interpretation is that

voters are more likely to feel that their vote could be decisive in a small country.

Still another interpretation, and the one I find the most plausible (although it is contradicted by Rose 2004), is that smaller countries have fewer electors per elected

member, which makes it easier for candidates and parties to mobilize the vote.

Not surprisingly, political scientists have paid closer attention to the impact

of institutions than to the effect of the socioeconomic environment. Still, extant

research shows that turnout is substantially lower in poor countries and exceptionally high in exceptionally small countries. Few other consistent patterns have

been reported. Given the prominence of the resource model in the field of political

participation (Brady et al. 1995), we would expect more systematic analyses of

how poverty and/or illiteracy affect turnout.

6 Apr 2006 15:59

118

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

PARTY SYSTEMS AND ELECTORAL OUTCOMES

Powells (1982) initial analysis indicated that turnout was higher in countries with

strong linkages between social groups and parties. That finding was not replicated

by Jackman (1987), and subsequent studies have left out this variable. Jackman

introduced a new variable, the number of parties, which is now incorporated in

most research.

The intuition is that turnout should be higher the more parties there are, for at

least two reasons. First, voters have more options to choose from. When there are

six or seven parties instead of two or three, voters are more likely to find a party

whose platform is reasonably close to their own views on the major issues of the

election, and they should be less inclined to feel that none of the options is satisfactory. Second, the more parties there are, the greater the electoral mobilization.

As Jackman points out, party fractionalization may also have negative consequences on turnout. The more parties there are, the greater the likelihood that the

government will be made of a coalition of parties. In systems that have coalition

governments, electoral outcomes are less decisive, because the final composition

of the government depends on the deals that parties are willing (or unwilling) to

make. The presence of many parties may mean that voters have little say in the

actual selection of the government (Downs 1957).

Because of these possible contradictory consequences, it is not clear whether we

should expect the correlation of turnout with the number of parties to be positive,

negative, or nonexistent. Moreover, it is not clear that it is the number of parties

per se that counts. If it is the decisiveness of the outcome that matters, then we

should look at the (anticipated) presence or absence of deals after the election

and the most important distinction could be between elections producing singleparty majority governments (which are decisive) and those producing minority or

coalition governments.

Almost all empirical research has found a negative correlation between the

number of parties and turnout (Jackman 1987, Blais & Carty 1990, Jackman &

Miller 1995, Blais & Dobrzynska 1998, Radcliff & Davis 2000, Kostadinova 2003).

The only exceptions are studies of turnout in Latin America, where there seems to

be no relationship (Perez-Lina n 2001, Fornos et al. 2004).

This is a perplexing finding. It seems to imply that people are not more inclined

to vote when and where there are more options to choose from, and/or that party

mobilization does not matter much (or that the arrival of new parties does not

enhance overall mobilization). Furthermore, the usual interpretation that a higher

number of parties reduces turnout because they produce coalition governments

(and elections are therefore less decisive) is not empirically supported. Blais &

Carty (1990) and Blais & Dobrzynska (1998) report that turnout is not higher in

elections that produce single-party majority governments.

The bottom line is that we have a poor understanding of the relationship between

the number of parties and turnout. We must reject the simple intuition that having

more parties fosters turnout. This is an important nil finding. PR and/or larger

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

119

district magnitude increases the number of parties (Taagepera & Shugart 1989,

Blais & Carty 1991, Lijphart 1994, Cox 1997). We can say that if PR fosters turnout,

it is not because it produces more parties. Because we do not know exactly how and

why PR may affect turnoutthat is, we do not understand the microfoundations

(Achen 2002)the pessimistic reading that there is no generalized correlation

between electoral system and turnout seems justified.

It is also time to question the standard interpretation that the often observed

negative correlation between the number of parties and turnout reflects the impact

of the decisiveness of elections. That interpretation must be directly tested, which

means developing measures of election decisiveness. Such measures have been

used in other streams of research (see, in particular, Powell & Whitten 1993); they

might have to be amended or refined, but they should be incorporated in future

studies. It could also be argued that what really matters is clarity of choice, that is,

voters need to know with relative certainty the coalitions that might be formed. If

that is the presumed process, then clarity-of-choice indicators must be constructed.

As things stand, the fact that turnout appears to be lower when there are more parties

is intuitively odd, and the supposition that this is so because more parties mean

less decisive elections is only a supposition. (I do not find the interpretation that

the number of parties increases information costs very plausible either. Voters do

not have to inform themselves about each party. Information costs may increase,

however, if and when the party system is in great flux.)

There is one final variable that was not included in the pioneer work of Powell

and Jackman but has been incorporated in many subsequent studies: the closeness

of the electoral outcome. This variable has produced the most consistent findings.

My earlier summary of the evidence still holds: the verdict is crystal clear with

respect to closeness: closeness has been found to increase turnout in 27 of the

32 studies that have tested the relationship, in many different settings and diverse

methodologies. There are strong reasons to believe that, as predicted by rational

choice theory, more people vote when the election is close (Blais 2000, p. 60).

This is the most firmly established result in the literature. I cannot see how this

finding could be wrong.

This does not mean that the issue is settled. It does not suffice to say that

closeness fosters turnout; we need to specify the magnitude of the impact. I have

been struck, in my own research, by its smallness. My cross-national analysis

suggests that turnout is reduced by one or two points when the gap between

the leading and the second parties increases by 10 points (Blais & Dobrzynska

1998). Very similar patterns emerge in cross-sectional analyses of constituency

level turnout (Loewen & Blais, unpublished)1 and time-series studies of national

turnout in Canada (Nevitte et al. 2000).

It is possible that the impact of closeness is underestimated because the variable

is not adequately measured. The standard indicator is the vote gap between the

1

Loewen PJ, Blais A. 2005. Did C-24 Affect Voter Turnout? Evidence from the 2000 and

2004 Elections. Typescript.

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

120

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

leading and second parties. The indicator makes sense, although it is not clear

whether it is the seat or the vote gap that matters. (I personally think it is the vote

gap because voters receive much information about vote intentions from polls

and because many have a poor understanding of how votes are translated into

seats.) In systems with coalition governments, it may be the closeness of the race

between the two major coalitions that matters. More complex measures need to

be constructed. Furthermore, it is always assumed that the relationship between

closeness and turnout is linear. It could be that what matters is that the outcome not

be a foregone conclusion, and that the real difference is between elections where

the winner wins by a very wide margin and all others. Or perhaps it is only very

close elections that excite voters and boost turnout.

Cross-national research typically looks at the overall closeness of the national

election. It could be that what matters is the closeness of the race at the district level.

Franklin (2004) uses mean margin of victory at the district level as an indicator of

closeness, and this is clearly an avenue worth exploring. We should not assume,

however, that closeness must absolutely be measured at the district level. In an

analysis of individuals decision to vote or abstain in the 1996 British Columbia

election, we found that the perceived closeness of the race at the provincial level

had a greater impact than perceived closeness at the district level (Blais et al. 2000).

Finally, there is the question of whether closeness matters in PR systems.

Franklin (2004) takes the radical view that the margin of victory matters only

in plurality systems. He may be right, but that is an empirical proposition that

should be directly tested. The most difficult question is whether closeness (or

competitiveness) should be measured the same way in different electoral systems.

Margin of victory is the logical indicator in plurality systems because the probability of casting a decisive vote is directly related to margin of victory. In a PR

system, however, the outcome can sometimes be a foregone conclusion even if it is

close. In a five-seat district, for instance, it may be obvious to voters that party A

and party B will each win two seats and party C one seat (and that could have been

the outcome of the previous three elections), yet party As lead over party B may

be minuscule. Such an outcome would be coded as very close, yet the probability

of casting a decisive vote in such a district would be as tiny as in single-member

noncompetitive districts. The probability of casting a decisive vote is equally

minuscule in PR and non-PR systems. We need to think hard about what closeness

or competitiveness actually means in PR systems.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The dominant view in the field is that cross-national variations in turnout can be

explained mostly by institutional factors that make some elections more salient and

competitive than others. That view is well expressed by Franklin (1996, p. 232):

A country with low salience elections and an electoral system that was not very

proportional could easily show turnout levels 40% [sic; it should be 40 percentage

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

121

points] below a country with high salience elections and a highly proportional

system. Such differences arise purely from differences in the institutional context

within which elections are conducted.

I am not convinced. As I have indicated, the evidence that turnout is higher

under PR (which is supposed to produce more competitive outcomes) and in more

important elections is far from robust. The evidence on the impact of closeness

is consistent, but that impact appears to be strikingly weak. Institutions matter less

than we are prone to believe. Their impact is conditional on the presence of other

factors.

In order to disentangle these more complex relationships, we need to reconsider our research designs and methodologies. The standard approach in the field

has been a cross-sectional analysis of variations in turnout across countries. This

approach is appropriate for sorting out the effect of variables that tend to be stable over time, such as the socioeconomic environment or the electoral system

and compulsory voting. The challenge is to include more cases, as the number of

democracies expands, so as to test the robustness of the findings observed among

established democracies.

But many variables differ from one election to another, and for these variables the analysis should be explicitly dynamic. In his ground-shaking work Voter

Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies Since 1945, Franklin (2004) confronts the issue of moving variables and

clearly points in the direction that future research should take (see also Franklin

et al. 2004). Franklin makes two crucial points. First, the logical way to ascertain

the impact of a variable on turnout is to examine whether turnout increases or decreases when that variable changes. In other words, the analysis should be dynamic.

Second, the impact of any change should be felt mostly on the new cohorts, who

have not yet developed a habit of voting (or abstaining).

This approach leads Franklin to perform empirical analyses in which previous

turnout is included as a control variable, thus making the analysis explicitly dynamic. Franklin also creates interactive variables between institutional factors and

the proportion of the electorate that is new (facing one of its first three elections).

In some cases, he also uses cohorts as the unit of analysis, which allows him to

directly test the hypothesis that institutional variables have a stronger effect on

new cohorts.

This is an impressive accomplishment. Franklin (2004) has challenged us to

revisit how to test hypotheses about the influence of institutions or party systems

on turnout. However, the study has three serious flaws. First, Franklin omits the

main effects associated with new cohorts in his estimations because of the presence of multicollinearity. This is not a compelling justification. Brambor et al.

(forthcoming) show that when the theoretical model entails interaction effects,

all the constitutive terms must be included and that the problems associated with

multicollinearity have been greatly overstated. Second, Franklin frequently refers

to how generational replacement affects turnout, yet he confines his analysis to

the consequences of new cohorts entering the electorate. He does not tackle the

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

122

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

crucial and difficult question of whether new cohorts vote less because they enter

politics in a less competitive context (his argument) or because they belong to a

new generation with a different set of values (Blais et al. 2004). Third, the kind

of model that Franklin proposes calls for the use of multilevel analysis, in which

characteristics of voters interact with characteristics of the electoral context.

Despite these shortcomings, Franklin has indicated the new direction that research in the field has to follow. We must pay closer attention to the dynamics

of turnout, we must examine how changes in the party system and/or closeness

of the election outcome affect electoral participation, and we should explicitly

test whether these factors have a greater impact on new cohorts. In that sense,

Franklins book is as much a pioneer study as Powells and Jackmans work

20 years ago.

Franklins central argument, which corresponds to the dominant view in the

field, is that the degree of electoral competition is the most crucial determinant of

turnout. I remain skeptical. As indicated above, turnout is only weakly affected by

the closeness of an election. Extremely close elections typically boost turnout

by a few percentage points. Furthermore, I have seen no evidence that elections

are becoming systematically less competitive over time, and so the recent decline

in turnout can hardly be attributed to the lack of competition.

Franklin alerts us to the possibility that the impact of institutional characteristics

may vary across types of voters. We must also examine the possibility that their

effects vary across systems. For instance, turnout may be differentially related

to the number of parties and/or the closeness of the election in PR and non-PR

countries. Likewise, what increases or decreases turnout may be quite different

in rich and poor countries. Because the number of democracies and democratic

elections is greatly expanding, it is now possible to test interaction effects between

the socioeconomic environment, institutional variables, and party systems and to

separate general patterns that hold everywhere from conditional ones that apply

only in some specific contexts.

CONCLUSION

Cross-national studies of turnout have produced a number of robust findings. We

can confidently say that turnout is lower in poor countries and higher in small

ones, that compulsory voting fosters turnout, and that turnout increases in closely

contested elections. But I am more impressed by the gaps in our knowledge. We

have a poor understanding of how compulsory voting enhances turnout, and we

have a poor appreciation of how much or little competition matters and of how

it plays out in PR systems. It makes sense to believe that turnout is lower in less

salient elections but what makes an election more or less salient is still obscure.

We can do better. As the number of democracies and the number of democratic

elections are greatly expanding, we can test our hypotheses with more cases and

with greater variance in both the dependent and independent variables. This means

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

123

we must move beyond established democracies and check whether the patterns that

we observe among them hold in new democracies. This is why the work of Fornos

et al. (2004), which tests some of the standard hypotheses about the determinants

of turnout in a new environment (Latin America), is so useful and important. If

some factors, such as the electoral system or district magnitude, appear to have

an impact only in some subset of countries, we should develop a more complex

theory about when and where they matter more and lessor we should perform

additional analyses to check whether the apparent relationship could be spurious.

With the advent of data sets such as the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, it also becomes possible to examine the conditional impact of institutions

on different types of voters (see, e.g., Long & Shively 2005). This opens up a

fascinating avenue of research. Franklin (2004), Gerber et al. (2003), and Plutzer

(2002) have all argued that there is an important habit component in voting. If

they are right, we should expect contextual factors to have a much greater effect

on new cohorts. That logically calls for a multilevel analysis linking institutional

variables with individual voter characteristics.

The Annual Review of Political Science is online at

http://polisci.annualreviews.org

LITERATURE CITED

Achen CH. 2002. Toward a new political

methodology: microfoundations and ART.

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 5:42350

Arcelus FJ, Meltzer AH. 1975. The effect of aggregate economic variables on congressional

elections. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 69:123265

Bilodeau A, Blais Andre. 2005. Le vote obligatoire a-t-il un effet de socialisation politique?

Presented to Colloque int. vote obligatoire,

Inst. dEtudes

Polit. Lille, Oct. 2021

Black JH. 1991. Reforming the context of the

voting process in Canada: lessons from other

democracies. In Voter Turnout in Canada, ed.

HI Bakvis, pp. 61176. Toronto: Dundurn

Blais A. 1991. The debate over electoral systems. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 12:23960

Blais A. 2000. To Vote Or Not To Vote? The

Merits and Limits of Rational Choice. Pittsburgh: Univ. Pittsburgh Press

Blais A, Aarts K. 2005. Electoral system

and turnout. Presented at Int. Expert Meet.

Changing the Electoral System: The Case

of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, Sept. 14

15

Blais A, Carty K. 1990. Does proportional representation foster voter turnout? Eur. J. Polit.

Res. 18:16781

Blais A, Carty K. 1991. The psychological impact of electoral laws: measuring Duvergers

elusive factor. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 21:7993

Blais A, Dobrzynska A. 1998. Turnout in electoral democracies. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 33:239

61

Blais A, Gidengil E, Nevitte N, Nadeau R. 2004.

Where does turnout decline come from? Eur.

J. Polit. Res. 43:22136

Blais A, Massicotte L, Dobrzynska A. 2003.

Why is Turnout Higher in Some Countries

than in Others? Ottawa: Elections Canada

Blais A, Young R, Lapp M. 2000. The calculus

of voting: an empirical test. Eur. J. Polit. Res.

37:181201

Brady HE, Verba K, Schlozman L. 1995. Beyond SES: a resource model of political

participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89:271

95

Brambor T, Roberts Clark W, Golder M.

2006. Understanding interaction models:

6 Apr 2006 15:59

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

124

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

BLAIS

improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal.

14:6382

Cox GW. 1997. Making Votes Count. New

York/London: Cambridge Univ. Press

Downs A. 1957. An Economic Theory of

Democracy. New York: Harper

Fornos CA, Power TJ, Garand JC. 2004. Explaining voter turnout in Latin America, 1980

to 2000. Comp. Polit. Stud. 37(8):90940

Franklin M. 1996. Electoral participation. In

Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective, ed. L LeDuc, RG

Niemi, P Norris, pp. 21635. Beverly Hills,

CA: Sage

Franklin M. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies Since 1945. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge Univ. Press

Franklin M, Lyons P, Marsh M. 2004. Generational basis of turnout decline in established

democracies. Acta Polit. 39:11551

Gerber AS, Green DP, Shachar R. 2003. Voting may be habit-forming. Am. J. Polit. Sci.

47:54050

Gimpel JG, Schuknecht JE. 2003. Political participation and the accessibility of the ballot

box. Polit. Geogr. 22:47188

Jackman RW. 1987. Political institutions and

voter turnout in industrial democracies. Am.

Polit. Sci. Rev. 81:40524

Jackman RW, Miller RA. 1995. Voter turnout in

the industrial democracies during the 1980s.

Comp. Polit. Stud. 27(4):46792

Kostadinova T. 2003. Voter turnout dynamics

in post-Communist Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res.

42(6):74159

Lijphart A. 1994. Electoral Systems and Party

Systems. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press

Lijphart A. 2000. Turnout. In International Encyclopedia of Elections, ed. R Rose, pp. 314

22. Washington, DC: CQ Press

Long JK, Shively WP. 2005. Applying a twostep strategy to the analysis of cross-national

public opinion data. Polit. Anal. 13:32744

Massicotte L, Blais A. 1999. Mixed electoral

systems: a conceptual and empirical survey.

Elect. Stud. 18:34166

Massicotte L, Blais A, Yoshinaka A. 2003.

Establishing the Rules of the Game: Election Laws in Democracies. Toronto: Univ.

Toronto Press

McDonald MP, Samuel P. 2001. The myth

of the vanishing voter. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.

95(4):96374

Nevitte N, Blais A, Gidengil E, Nadeau R. 2000.

An Unsteady State: The 1997 Canadian Federal Election. Toronto: Oxford Univ. Press

Norris P. 2002. Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. New York:

Cambridge Univ. Press

Oliver JE. 2000. City size and civic involvement

in metropolitan America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.

94:36173

Perez-Lina n A. 2001. Neoinstitutional accounts

of voter turnout: moving beyond industrial

democracies. Elect. Stud. 20(2):28197

Plutzer E. 2002. Becoming a habitual voter: inertia, resources and growth in young adulthood. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 96:4156

Powell GB. 1982. Comparative Democracies:

Participation, Stability and Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press

Powell GB Jr. 1986. American voter turnout in

comparative perspective. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.

80(1):1743

Powell GB, Whitten GD. 1993. A crossnational analysis of economic voting: taking

account of the political context. Am. J. Polit.

Sci. 37:391414

Radcliff B. 1992. The welfare state, turnout, and

the economy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 86:44456

Radcliff B, Davis P. 2000. Labor organization and electoral participation in industrial

democracies. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 44(1):13241

Rallings C, Thrasher M. 2006. The turnout

gap and the costs of voting: a comparison

of participation at the 2001 general and 2002

local election in England. Br. J. Polit. Sci. In

press

Rose R. 2004. Voter turnout in the European

Union member vountries. In Voter Turnout

in Western Europe since 1945, ed. R Lopez

Pintor, M Gratschew, pp. 1724. Stockholm:

Int. IDEA

Rosenstone SJ. Economic adversity and voter

turnout. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 26:2546

6 Apr 2006 15:59

AR

ANRV276-PL09-06.tex

XMLPublishSM (2004/02/24)

P1: KUV

WHAT AFFECTS TURNOUT?

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

Siaroff A, Merer JWA. 2002. Parliamentary

election turnout in Europe since 1990. Polit.

Stud. 50:91627

Southwell PL. 2004. Five years later: a reassment of Oregons vote by mail electoral process. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 37:8993

125

Taagepera R, Soberg Shugart M. 1989. Seats

and Votes: The Effects and Determinants

of Electoral Systems. New Haven, CT: Yale

Univ. Press

Wolfinger RE, Rosenstone SJ. 1980. Who

Votes? New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press

P1: JRX

April 5, 2006

20:54

Annual Reviews

AR276-FM

Annual Review of Political Science

Volume 9, 2006

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

CONTENTS

BENTLEY, TRUMAN, AND THE STUDY OF GROUPS, Mika LaVaque-Manty

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF LEGISLATURES IN THE UNITED STATES,

Peverill Squire

RESPONDING TO SURPRISE, James J. Wirtz

POLITICAL ISSUES AND PARTY ALIGNMENTS: ASSESSING THE ISSUE

EVOLUTION PERSPECTIVE, Edward G. Carmines and Michael W. Wagner

PARTY POLARIZATION IN AMERICAN POLITICS: CHARACTERISTICS,

CAUSES, AND CONSEQUENCES, Geoffrey C. Layman, Thomas M. Carsey,

and Juliana Menasce Horowitz

WHAT AFFECTS VOTER TURNOUT? Andre Blais

PLATONIC QUANDARIES: RECENT SCHOLARSHIP ON PLATO,

Danielle Allen

ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION AND ITS POLITICAL DISCONTENTS IN

CHINA: AUTHORITARIANISM, UNEQUAL GROWTH, AND THE

DILEMMAS OF POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, Dali L. Yang

MADISON IN BAGHDAD? DECENTRALIZATION AND FEDERALISM IN

COMPARATIVE POLITICS, Erik Wibbels

SEARCHING WHERE THE LIGHT SHINES: STUDYING

DEMOCRATIZATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Lisa Anderson

POLITICAL ISLAM: ASKING THE WRONG QUESTIONS? Yahya Sadowski

RETHINKING THE RESOURCE CURSE: OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE,

INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY, AND DOMESTIC CONSTRAINTS,

Pauline Jones Luong and Erika Weinthal

A CLOSER LOOK AT OIL, DIAMONDS, AND CIVIL WAR, Michael Ross

THE HEART OF THE AFRICAN CONFLICT ZONE: DEMOCRATIZATION,

ETHNICITY, CIVIL CONFLICT, AND THE GREAT LAKES CRISIS,

Crawford Young

1

19

45

67

83

111

127

143

165

189

215

241

265

301

PARTY IDENTIFICATION: UNMOVED MOVER OR SUM OF PREFERENCES?

Richard Johnston

REGULATING INFORMATION FLOWS: STATES, PRIVATE ACTORS,

AND E-COMMERCE, Henry Farrell

329

353

vii

P1: JRX

April 5, 2006

viii

20:54

Annual Reviews

AR276-FM

CONTENTS

COMPARATIVE ETHNIC POLITICS IN THE UNITED STATES: BEYOND

BLACK AND WHITE, Gary M. Segura and Helena Alves Rodrigues

WHAT IS ETHNIC IDENTITY AND DOES IT MATTER? Kanchan Chandra

NEW MACROECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE, Torben Iversen

and David Soskice

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2006.9:111-125. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA on 06/14/06. For personal use only.

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN CASE STUDY

METHODS, Andrew Bennett and Colin Elman

FOREIGN POLICY AND THE ELECTORAL CONNECTION, John H. Aldrich,

Christopher Gelpi, Peter Feaver, Jason Reifler,

and Kristin Thompson Sharp

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOCRACY, James A. Robinson

375

397

425

455

477

503

INDEXES

Subject Index

Cumulative Index of Contributing Authors, Volumes 19

Cumulative Index of Chapter Titles, Volumes 19

ERRATA

An online log of corrections Annual Review of Political Science chapters

(if any, 1997 to the present) may be found at http://polisci.annualreviews.org/

529

549

552

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Turnout in Electoral Democracies: January 1998Document24 paginiTurnout in Electoral Democracies: January 1998VerónicaWagnerGuillotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistical Model For Multiparty Electoral Data: Jonathan Katz Gary KingDocument18 paginiStatistical Model For Multiparty Electoral Data: Jonathan Katz Gary KingJesús Rafael Méndez NateraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Diversity and Duverger: Evidence From South African Local ElectionsDocument49 paginiSocial Diversity and Duverger: Evidence From South African Local Electionsرمزي العونيÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mainwaring e ZocoDocument24 paginiMainwaring e ZocoPaulo Anós TéÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral College Partisan BiasDocument21 paginiElectoral College Partisan BiasDJL ChannelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Background of Political Parties in PunjabDocument12 paginiBackground of Political Parties in PunjabJyoti Arvind PathakÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 - Lupu - Partisanship in Latin AmericaDocument20 pagini2015 - Lupu - Partisanship in Latin AmericaJeferson Ramos Dos SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral MagnitudeDocument11 paginiElectoral MagnitudeRafael Dos Anjos MonteiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Majoritarian and Proportional Visions and Democratic ResponsivenessDocument9 paginiThe Majoritarian and Proportional Visions and Democratic ResponsivenessKeep Voting SimpleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Álvarez y Nagler - Party System Compactness - Measurement and ConsequencesDocument17 paginiÁlvarez y Nagler - Party System Compactness - Measurement and ConsequencesAbraham TorroglosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral Systems and Party Systems: Which Drives Change and Which is ImpactedDocument15 paginiElectoral Systems and Party Systems: Which Drives Change and Which is ImpactedBoavida Simia Penicela100% (1)

- 04 Norris - Choosing Electoral Systems PDFDocument17 pagini04 Norris - Choosing Electoral Systems PDFHristodorescu Ana-IlincaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Mainwaring May 4 2017Document41 pagini3 Mainwaring May 4 2017Sofía RamírezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Party Polarization and Mass PartisanshipDocument26 paginiParty Polarization and Mass PartisanshipNadeem KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why electoral systems impact governanceDocument17 paginiWhy electoral systems impact governanceSamuel JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Canadian Electoral System: A Case For Proportional RepresentationDocument9 paginiThe Canadian Electoral System: A Case For Proportional RepresentationCaroline EwenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-National AnalysisDocument16 paginiElectoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-National AnalysisMoody AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- DemocracyDocument301 paginiDemocracyTihomir RajčićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral Systems and Election Management ExplainedDocument35 paginiElectoral Systems and Election Management ExplainedMohammad Salah KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2006 - Do Polls InBuence The Vote - UnlockedDocument17 pagini2006 - Do Polls InBuence The Vote - UnlockedFERMO RAMOSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Party Ideology, Organization, and Competitiveness-Hill1993Document22 paginiParty Ideology, Organization, and Competitiveness-Hill1993Ishaq YudhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anchor Variables and The VoteDocument9 paginiAnchor Variables and The VoteMarian TrujilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perspectives on Future Trends in Electoral Behavior ResearchDocument11 paginiPerspectives on Future Trends in Electoral Behavior ResearchAmado Rene Tames GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blais, Dobrzynska - Turnout in Electoral DemocraciesDocument23 paginiBlais, Dobrzynska - Turnout in Electoral DemocraciesCarlos LópezÎncă nu există evaluări

- André Blais & R. K. CartyDocument16 paginiAndré Blais & R. K. Cartyakmuzakkir07Încă nu există evaluări

- Turnout JOP 2009 Pacek PopEleches TuckerDocument19 paginiTurnout JOP 2009 Pacek PopEleches Tuckerstefania0912Încă nu există evaluări

- Parties For Rent? Ambition, Ideology, and Party Switching in Brazil's Chamber of DeputiesDocument19 paginiParties For Rent? Ambition, Ideology, and Party Switching in Brazil's Chamber of DeputiesclaudiacerqnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curini2019 PDFDocument11 paginiCurini2019 PDFAjideniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curini2019 PDFDocument11 paginiCurini2019 PDFAjideniÎncă nu există evaluări

- PollsMedia 2012 MoyRinke PollConsequences PreprintDocument32 paginiPollsMedia 2012 MoyRinke PollConsequences PreprintOmfo GamerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sage Publications, Inc. University of UtahDocument15 paginiSage Publications, Inc. University of UtahHan Tun LwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Politicians, Parties and Electoral Systems: Brazil in Comparative PerspectiveDocument33 paginiPoliticians, Parties and Electoral Systems: Brazil in Comparative PerspectiveStela LeucaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Systems,: CaliforniaDocument22 paginiSystems,: CaliforniafrostyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golder 2006Document21 paginiGolder 2006micaela.mazza0902Încă nu există evaluări

- Lectura de Field Experiments and The Study of Voter TurnoutDocument11 paginiLectura de Field Experiments and The Study of Voter TurnoutAndrea CastañedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brancati Dawn PDFDocument15 paginiBrancati Dawn PDFLibertadRmrTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implementation of Political Party Gender Quotas: Evidence From The German Länder 1990-2000Document22 paginiImplementation of Political Party Gender Quotas: Evidence From The German Länder 1990-2000Alejandro LiévanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gallagher & Mitchell's Guide to Electoral SystemsDocument12 paginiGallagher & Mitchell's Guide to Electoral Systemschatnoir910Încă nu există evaluări

- Döring Manow 2016Document16 paginiDöring Manow 2016Alex PriuliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voting PatternsDocument31 paginiVoting Patternsstefania0912Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction PDFDocument22 paginiIntroduction PDFSergioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reasons For The Continued Survival of The United StatesDocument9 paginiReasons For The Continued Survival of The United Statesapi-455036018Încă nu există evaluări

- Democracy and Dictatorship RevisitedDocument35 paginiDemocracy and Dictatorship RevisitedGuilherme Simões ReisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Explaining Turnout Decline in Britain, 1964-2005: Party Identification and The Political ContextDocument24 paginiExplaining Turnout Decline in Britain, 1964-2005: Party Identification and The Political Contextzhan ChenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mozaffar and Schedler 2002Document24 paginiMozaffar and Schedler 2002gabrielatarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fallacy of Electoral AccountabilityDocument30 paginiThe Fallacy of Electoral AccountabilityrvaldezsaldanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heterotemporal Parliamentarism. Staggered Membership Renewal and Its EffectsDocument38 paginiHeterotemporal Parliamentarism. Staggered Membership Renewal and Its Effectsniall BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pippa Norris The Concept of Electoral Integrity Forthcoming in Electoral StudiesDocument33 paginiPippa Norris The Concept of Electoral Integrity Forthcoming in Electoral StudiesjoserahpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missing Voters, Multiple Imputation: Estimating Low Turnout EffectsDocument41 paginiMissing Voters, Multiple Imputation: Estimating Low Turnout Effectsxaxilus1675Încă nu există evaluări

- Jones 2003Document29 paginiJones 2003Jo losojosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 07 Boix - Setting The Rules of The Game The Choice of Electoral Systems in Advanced DemocraciesDocument17 pagini07 Boix - Setting The Rules of The Game The Choice of Electoral Systems in Advanced DemocraciesAndra BistriceanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Votes For Women Electoral Systems and Support For Female CandidatesDocument25 paginiVotes For Women Electoral Systems and Support For Female CandidatesGustavo MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- U1-Lupu OliverosSchiumeriniDocument44 paginiU1-Lupu OliverosSchiumeriniLauritoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Pressure and Voter Turnout: Evidence From A Large-Scale Field ExperimentDocument16 paginiSocial Pressure and Voter Turnout: Evidence From A Large-Scale Field ExperimentRalphYoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electoral Reform Research ApproachesDocument23 paginiElectoral Reform Research ApproachesGonzaloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moving Apart: Political Strategies Adopted by Unions and The Alp To Manage Their Diminished RelationshipDocument11 paginiMoving Apart: Political Strategies Adopted by Unions and The Alp To Manage Their Diminished RelationshipTrevor CookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guinjoan 2013Document15 paginiGuinjoan 2013fermo ii ramosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voters’ Verdicts: Citizens, Campaigns, and Institutions in State Supreme Court ElectionsDe la EverandVoters’ Verdicts: Citizens, Campaigns, and Institutions in State Supreme Court ElectionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- By Election Report CouncilDocument2 paginiBy Election Report CouncilCity of SaskatoonÎncă nu există evaluări

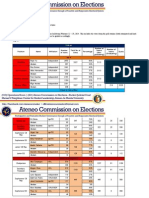

- COMELEC Memo 201411 - 2014 General Elections ResultsDocument18 paginiCOMELEC Memo 201411 - 2014 General Elections ResultsAteneo COMELECÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rochester 2020 Election ResultsDocument8 paginiRochester 2020 Election ResultsportsmouthheraldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labour Law CasesDocument26 paginiLabour Law Casesprakhar bhattÎncă nu există evaluări

- Small Group Communication Techniques (James Patrick A. Olivar)Document72 paginiSmall Group Communication Techniques (James Patrick A. Olivar)James Patrick OlivarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polls Apart 2010Document55 paginiPolls Apart 2010Vaishnavi JayakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 4 PDFDocument77 pagini01 4 PDFCitizen StringerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 Chapter 2Document27 pagini09 Chapter 2Nikhil KalyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion To Amend Previously AdoptedDocument2 paginiMotion To Amend Previously AdoptedRose BerryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labour Law Concept of Standing OrdersDocument16 paginiLabour Law Concept of Standing OrdersShubhankar ThakurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secured Biometric Voting MachineDocument14 paginiSecured Biometric Voting Machinesumit sanchetiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The HISTORIANS Club Constitution and Bylaws Guidelines Real 2Document5 paginiThe HISTORIANS Club Constitution and Bylaws Guidelines Real 2Arcaileon Adrailmo0% (1)

- Rules For AppreciationDocument40 paginiRules For AppreciationGringo B. Oliva100% (1)

- POSTAL BALLOT PROCEDURESDocument54 paginiPOSTAL BALLOT PROCEDURESNaveen KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook AISMUN 2012Document34 paginiHandbook AISMUN 2012Altamira International SchoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apportionment Problem: District PopulationDocument3 paginiApportionment Problem: District PopulationAndrea Rubi LantacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft Photo Electoral Roll, State - Andhra Pradesh 2014: 1. Details of RevisionDocument31 paginiDraft Photo Electoral Roll, State - Andhra Pradesh 2014: 1. Details of RevisionpattabhikvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blais, Dobrzynska - Turnout in Electoral DemocraciesDocument23 paginiBlais, Dobrzynska - Turnout in Electoral DemocraciesCarlos LópezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement by Macomb County Clerk Fred MillerDocument1 paginăStatement by Macomb County Clerk Fred MillerWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Form For Inclusion of Names in Electoral RollDocument2 paginiApplication Form For Inclusion of Names in Electoral RollN Rakesh100% (6)

- Omnibus Election CodeDocument25 paginiOmnibus Election CodeEdmarjan ConcepcionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case For MI DecertificationDocument86 paginiCase For MI DecertificationrealtalkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standing Order PDFDocument6 paginiStanding Order PDFIbban JavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Election Day 2019Document2 paginiElection Day 2019Lia Khusnul KhotimahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brief History of Parliamentary Law OriginsDocument6 paginiBrief History of Parliamentary Law OriginsMaria Cecilia ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ri Rla Report 2020Document47 paginiRi Rla Report 2020Verified VotingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawDocument20 paginiEclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawNandini TarwayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics As A Tool: Apportionment and VotingDocument16 paginiMathematics As A Tool: Apportionment and Votingbasty dyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manorville Fire District Election NoticeDocument1 paginăManorville Fire District Election NoticeRiverheadLOCALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evoting, 2023 3Document7 paginiEvoting, 2023 3sameer43786Încă nu există evaluări