Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Building Citizen Trust Through E Government 2005 Government Information Quarterly

Încărcat de

almirb7Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Building Citizen Trust Through E Government 2005 Government Information Quarterly

Încărcat de

almirb7Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720 736

Building citizen trust through e-government

Michael ParentT, Christine A. Vandebeek, Andrew C. Gemino

Faculty of Business Administration, Simon Fraser University, 515 West Hastings Street,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6B 5K3

Available online 1 December 2005

Abstract

The trust of citizens in their governments has gradually eroded. One response by several North

American governments has been to introduce e-government or Web-mediated citizen-to-government

interaction. This paper tests the extent to which online initiatives have succeeded in increasing trust and

external political efficacy in voters. An Internet-based survey of 182 Canadian voters shows that using

the Internet to transact with the government had a significantly positive impact on trust and external

political efficacy. Interestingly, though the quality of the interaction was important, it was secondary to

internal political efficacy in determining trust levels, and not significant in determining levels of external

political efficacy (or perceived government responsiveness). For policymakers, this suggests egovernment efforts might be better aimed at citizens with high pre-extant levels of trust rather than in

developing better Web sites. For researchers, this paper introduces political efficacy as an important

determinant of trust as it pertains to e-government.

D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, Lincolns dictum, bgovernment of the people, for the people, by the

peopleQ, has been used to define a democracy. Yet, the state of affairs is far from this ideal. The

trust of American citizens in their government has declined dramatically over the past thirty

years.1,2 Beliefs that the government is getting worse instead of better and that todays public

4 Corresponding author. Fax: +1 604 291 5153.

E-mail address: mparent@sfu.ca (M. Parent).

0740-624X/$ - see front matter D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.giq.2005.10.001

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

721

officials simply do not measure up are increasingly in vogue in political dialogue.3 Declining

turnout in federal elections also suggests that the North American public has lost confidence in

the fundamental features of representative democracy. From the perspective of policymakers,

trust and political efficacy may be viewed as preconditions for electoral success.

A variety of strategies for dealing with distrust have been investigated. Among the most

popular is that the deficit in trust can be made up by greater public participation in decisions.4

Encouraging citizens to exercise their bvoiceQ clearly aims to reinstate confidence in the

overhead democracy to rebuild the political efficacy of citizens. Some argue that the

reciprocation of goods and services of extrinsic value has more resonance with citizens than

overhead democracy.57

Some regard e-government as a powerful tool for improving the internal efficiency of the

government and the quality of service delivery as well as enhancing public participation. The

Gartner Group defines e-government as b. . .the continuous optimization of service delivery,

constituency participation and governance by transforming internal and external relationships

through technology, the Internet and new mediaQ.8 However, e-governments contribution to

political capital remains largely underinvestigated. Could e-government be a panacea for

citizen dissatisfaction? This question is addressed in this paper through a survey of voters.

2. Background and literature review

Three streams inform this research: political trust; political self-efficacy; and e-government, a tool for rebuilding both preceding elements.

2.1. Political trust

Easton first defined and delineated the types of trust in the government as being specific and

diffuse.9 Specific support refers to satisfaction with government outputs and the overall

performance of political authorities. Diffuse support refers to the publics attitude toward

regime-level political objects, regardless of performance. Specific support encapsulates the

economic value of the exchange between citizen and the government, whereas diffuse support

encapsulates the intrinsic.

The literature on citizen trust is not merely abstract sociodemocratic theory. Rather, it

evidences the role of trust in building political capital. Hetherington offered empirical evidence

that political trust affects voting behavior: distrustful voters are more likely to support nonincumbent and third party candidates.10 Prior research found that distrustful voters are also

more likely to express support for the devolution of federal decision making to provincial

governments.11 Belanger and Nadeau showed that trust in the government also has a significant

effect on voting behavior.12

Thomas outlined three means by which trust in the government is produced.13 The first,

characteristic-based, is produced through expectations associated with the demographic

characteristics of a person. Secondly, institutions may create trust either directly through

adoption of professional standards or codes of ethics, or indirectly through the observance or

722

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

administration of laws and regulations. Third, process-based trust results from expectations of

reciprocity in which the giver obligates the receiver to return goods or services of equivalent

bintrinsic or economic valueQ. Nye classified these causal factors as social-cultural, economic or

political.14

Implicit in Thomas definition of process-based trust are the evaluative actions citizens

undertake; reciprocation is measured against expectations.

There is an abundance of literature establishing that levels of trust rise and fall with the

publics evaluation of the economy.5,7,15 Hibbing and Patterson also established that

optimistic economic perceptions are correlated with support for European parliaments.16

However, Mansbridge pointed out that citizens expect the government to perform the

impossible feat of a continually growing economy without recessions.17 Secondly, almost

universally, there is strain on public budgets and governments are under pressure to increase

the efficiency and performance of agencies. Inglehart hypothesized that these rising

expectations are a result of economic development; citizens began to expect more material

comfort in their lives and greater material security from their governments.18 Mansbridge also

calls attention to the growing bculture of rightsQ in North America as responsible for the rising

expectations of the government.17 Rising expectations, unmatched by improved performance,

will lower the publics evaluation of the government.

In some cases, goods and services of extrinsic value that are reciprocated for taxes are

measured by expectations rather than against expectations. In these cases, citizens

perceptions of government performance may stray from reality. For instance, Bok refers to

the widespread impression among the American public that government inefficiency wastes

tax money; public opinion polls suggest that Americans believe that forty-eight cents of every

tax dollar is squandered.19 At the same time, a National Performance Review was conducted

and its recommendations were expected to conserve no more than two extra cents for every

tax dollar.19 For the most part, the economic evaluation of citizens that has been linked to

trust captures public expectations of the future economy. It is worth noting that negative

biases towards the government bring Americans to a similar economic evaluation even if the

actual performance of the economy and their own economic circumstances may indicate the

opposite.20

However, the significance of economic factors cannot be dismissed. While it may be

difficult for the average citizen to articulate the reasons underlying their distrust, it is notable

that the primary reasons cited for distrusting the government are government inefficiency or

misallocated tax dollars.6 When citizens cite governments bspending money on the wrong

thingsQ as a reason for distrust, they are speaking of more than inefficiency. Lawrence

identified that perceptions that the government is responsive to the needs of special interests

and remote from the interests of ordinary citizens have also increased (along with

wastefulness) as trust has declined.

2.2. Political self-efficacy

These social, economic, and political dimensions of trust cannot be divorced from the

concept of political efficacy, an offspring of research on self-efficacy in general. Compeau

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

723

and Higgins defined computer self-efficacy as b. . .the belief that one has the capability to

perform a particular behaviorQ.21 This definition is based on Banduras earlier definition:

bPeoples judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to

attain designated types of performances. It is concerned not with the skills one has but with

judgments of what one can do with whatever skills one possesses.Q22 Political self-efficacy is

in turn both endogenous and exogenous and generally defined as the citizens sense that they

can have an impact on political developments (internal political efficacy) and their perception

of government responsiveness (external political efficacy).

A number of researchers have used Hirschmans model of exit, voice, and loyalty to

explain citizen reaction to deteriorating service.12,23 Hirschmans model proposed that

individuals react in two ways: they may attempt to effect change by expressing, or switch to

another organization, the latter depending on their loyalty.24 Although citizens cannot switch

governments on a whim, they may choose to bexitQ by staying home on Election Day.12

The sets of expectations guiding behavior, proposed by Bandura,22 may shed light on

citizens choice to register their dissatisfaction by abstention or by voice. Abstention might be

seen as a vote of no confidence in the electoral process. But rather than a blanket exit from

democratic processes, citizens may associate voice with better outcomes. Empirical evidence

of a positive relationship between external political efficacy and turnout corresponds with a

citizens consideration of expected outcomes.25,26 Thus, the expectation of outcomes, or

government responsiveness, cannot be entirely divorced from citizens self-efficacy.

Roese also provided evidence that the extent to which Canadians were becoming more

politically active and the degree to which their sense of control over their own destinies was

changing were predictors of trust in the government.27

2.3. E-government

Causes of non-confidence in the democratic process and the government are complex and

never exhaustive but public perceptions of inefficiency (wastefulness), ineffectiveness, and

policy alienation are among those that have been empirically proven.3,7,28

Although the catalysts for e-government initiatives may be multifaceted, some regard egovernment as a powerful tool for improving the internal efficiency of the government and

the quality of service delivery as well as enhancing public participation.2931 Theoretically,

distrust could be countered by increasing perceived efficiency, quality of outcomes, and

opportunities for policy inputs. The latter may also renew a citizens sense of political

efficacy.

Northrup and Thorson summarize three positive claims increased efficiency, increased

transparency, and transformation that have been used to support e-government initiatives.32

Welch and Hinnant related transparency and interactivity to citizen trust.4 However, they

concluded that Internet use and familiarity with e-government are only positively related to

transparency. Thus, the negative relation to interactivity is an artifact of the predominance of

one-way e-government.

E-government has evolved from one-way e-government consisting of posted contact and

program information. Its earliest incarnations consisted of posting contact and program

724

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

information on a Web site. It has since evolved to include citizen-initiated transactions. Citizeninitiated transactions, such as the Government of Canadas online income tax filing, have

enjoyed unexpected success.33 Moon proposed that IT- and Web-based public services can help

governments to restore public trust by coping with corruption, inefficiency, ineffectiveness, and

policy alienation.34 When bearing in mind the reciprocity expected in process-based trust,35

two-way government bears even greater potential than one-way government.

It may be obvious that e-government has no positive effect when the citizens experience

of these electronic transactions is negative. Yet, research on measuring satisfaction with

e-government services has been sparse and inconclusive with regards to overall trust. If

political capital is broadly defined as something employed to serve a political purpose,36

e-government presents itself as a tool deserving further investigation.

3. Research model

The foregoing discussion of the political consequences of declining trust and political

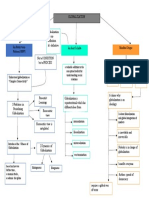

efficacy leads to the research model and hypotheses in Fig. 1.

The research model posits citizen trust and external political efficacy as effect variables

that are important to the policymakers in the federal government in the following

hypotheses. Empirical evidence has established that a citizens self-efficacy and political

involvement predict trust in government. Thus, a citizens sense of political efficacy should

do the same.

H1a: The greater the individuals internal political efficacy, the greater will be the trust in

government.

Following Banduras theory, the very choice of exiting from the electoral process or

exercising voice is predicated on a citizens belief in their ability to register dissatisfaction and

has an impact on political developments. The two may work in tandem.

H1b: The greater the individuals internal political efficacy, the greater will be external

political self-efficacy.

Fig. 1. Research model & hypotheses.

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

725

Following the suggestion that e-government can counter perceptions of inefficiency and

ineffectiveness, levels of trust were expected to be significantly higher among those who had

a positive transaction experience.

H2a: The greater the quality of the electronic transaction, the greater will be the individuals

trust in government.

Finally, the quality of the transaction should also contribute to increased perceptions of

government responsiveness.

H2b: The greater the quality of the electronic transaction, the greater will be the individuals

external political efficacy.

4. Research method

In order to test this model, an Internet-based survey of Canadian voters was conducted. To

ensure representation from all Canadians, the survey was also translated and offered in

French. Permission to post an invitation was requested from moderators of forty-four

Canadian public listservs and express agreement was obtained from six. Interested listserv

subscribers were directed to the online survey by way of a link. Informed consent was

obtained and surveys were received from 199 respondents, received between May 5 and June

10, 2003. Two surveys were removed because respondents were younger than nineteen years

old (the minimum voting age). Two surveys were rejected as incomplete. Of the 195

completed surveys, 44 percent of respondents were male and 56 percent were female.

Seventeen were completed in French. Seventy-one participants who indicated that they had

not used an e-government service within the previous six months were excluded from our

analysis. Of the e-government users, 38 percent were male and 62 percent were female.

Demographic characteristics are shown below in Table 1.

4.1. Measures

Pre-existing, validated, and reliable measures were used in this model. Internal and

external political efficacy were measured using scales developed by Craig et al. for the

National Election Studies.37

To test whether the experience with e-government impacted trust and political efficacy,

respondents were asked to indicate whether they had used any of a number of online services in

the past six months. The response options were chosen by reviewing e-services specified on the

Government of Canada Web site.38,39 Services consisting only of posted information,

downloadable forms, or generic tools in which no personal information was transferred were

not included.

Devaraj et al. used a hybrid of progressive instruments to measure consumer satisfaction

with the e-commerce channel.40 Applicable dimensions were applied to the e-government

context. A summated index measuring trust in the government was introduced to the

American National Election Studies in 1958.41 Respondents were asked how often they trust

726

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

Table 1

Sample demographics

Trait

Age

1924

2529

3034

3539

4044

4549

5054

55 or older

Province

Alberta

British Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

New Foundland

NWT/Nunavut

Nova Scotia

Ontario

PEI

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Education

High school or less

Some post-secondary

College

Bachelor degree

Some graduate studies

Masters degree

Some doctoral

Doctorate

Income

Less than $20,000

$20,00039,999

$40,00059,999

$60,00079,999

$80,00099,999

$100,000 or more

Party affiliation

Liberal

Conservative

NDP

Alliance

Other

None

% E-government

users (N = 124)

% Survey sample

(N = 195)

% Censusa,b,c

31.5

29.0

12.0

10.5

4.8

8.1

2.4

1.6

30.4

26.8

13.9

9.3

4.6

3.1

4.6

7.1

8.9

9.4

10.5

11.5

10.6

9.2

30.8

11.6

27.3

5.0

4.1

1.7

0.8

4.1

29.8

0.8

12.4

2.5

14.2

23.2

4.7

2.6

1.6

0.5

5.3

33.2

0.5

12.1

2.1

10.0

13.1

3.7

2.4

1.6

0.2

3.0

38.7

0.4

23.7

3.1

1.6

19.4

8.1

24.2

11.3

21.8

8.9

4.8

1.0

20.6

7.2

22.2

11.3

21.1

10.8

5.7

51.7

35.6

16.0

20.2

14.0

18.7

15.9

16.8

16.8

17.8

13.7

16.7

19.0

17.8

16.1

16.7

39.8

7.6

23.7

3.4

0.8

24.6

43.1

5.7

24.7

5.7

1.7

19.0

3

1

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

727

the government to do what is right, whether the government is run by a few big interests (or

conversely, for the benefit of all people), whether it wastes tax money, and whether people

running the government are crooked. The reliability of the trust index is 0.76. This instrument

was adapted to the Canadian political context by Converse et al. and used in this research to

measure Trust.42

Devaraj et al. used a hybrid of progressive instruments to measure consumer satisfaction with

the e-commerce channel.40 Applicable dimensions were modified to the e-government context.

For example, bonline shoppingQ was changed to read bonline government servicesQ. The quality

of the e-government experience was first measured using the Assurance dimension of the

SERVQUAL instrument.43 Orlikowski and Iacono proposed that the Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM) represents a consumers internal costbenefit analysis.44 Thus, both the

perceived ease of use and the perceived usefulness dimensions were also used in measuring this

construct. Lastly, as the quality of the service experience has a temporal dimension,45 time was

added.

Several other independent variables, including sociodemographic variables such as selfreported Internet ability and party affiliation, were added as controls.

5. Results

The model in Fig. 1 was analyzed using maximum likelihood estimation method employed

in Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 4.0. AMOS enables the simultaneous

estimation of both measurement and structural equations contained within the model. This

type of approach is appropriate to deal with the fit of the theoretical model to observed data.46

Constructs were operationalized using reflective measures. To set a unit of measurement for

each of the constructs, a path coefficient for one of the reflective measures was set equal to 1

and the path coefficient for each measure error term was also set to 1.

5.1. Tests of model fit

Before results from the estimation are examined, the model fit should be established. The

statistics reported below are consistent with those suggested by Gefen et al.46 Fitting the

model to the sample data resulted in a chi-square (v 2) statistic of 56.04 (df = 48, n = 125,

P b 0.000), a v 2/df ratio of 1.17, a goodness of fit index (GFI) value of 0.936, and the

goodness of fit adjusted for degrees of freedom (AGFI) of 0.896. The v 2/df ratio indicates

Notes to Table 1:

a

Statistics Canada. (2003). Estimates of population, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories,

annual. Retrieved February 20, 2003, from: http://www.statcan.ca/english/Pgdb/demo10a.htm.

b

Statistics Canada. (2003). Estimates of population, Canada, provinces and territories, quarterly (persons).

Retrieved February 20, 2003, from: http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/031218/d031218c.htm.

c

Statistics Canada. (2003). Education in Canada: Raising the standard [Catalogue Number 96F0030

XIE2001012]. Retrieved September 14, 2003, from: http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/

Analytic/companion/educ/canada.cfm#levels.

728

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

an acceptable level of fit as it satisfies the requirement of being less than 3.0.47 The GFI

indicates an acceptable fit with GFI N 0.90,47,48 as does the AGFI with a value of 0.86

which is above the suggested 0.80 level.49 The root mean square residual is 0.082 that is

above the 0.05 level and indicates a marginal fit.

Because the theory underlying the model is not well established, the comparative fit index

(CFI) is also recommended47 and provides an acceptable level of 0.986.47,50 The normed fit

index (NFI) also provides an acceptable fit with a value of 0.911. The root mean square error of

approximation (RMSEA) is 0.037 and indicates an acceptable fit with the 0.08 recommended

level.49 With a majority of fit measures in the acceptable level, there is adequate indication of an

acceptable level of fit for the model. A summary is provided in Table 2.

5.2. Test of the measurement model

Having found an arguably acceptable overall fit for the model, the measurement model can

be assessed. Convergent validity was tested for unidimensionality and reliability. Unidimensionality was tested by examining factor loadings for each measure in the model. An

accepted heuristic for convergent validity is a GFI N 0.90 combined with an insignificant v 2

and factor loadings above 0.70.47,48 The measurement model provided in Fig. 2 meets these

criteria, except for one item used to reflect internal political efficacy, one item for external

political efficacy, and two items for trust.

Because some questions in the reliability of constructs had emerged in the consideration of

unidimensionality, each constructs reliability was also assessed. Table 3 summarizes the

composite reliability and variance extracted for each construct. All of the scales met Nunallys

minimum criteria of 0.70 for reliability.51 The scales also achieved 0.50 for variance

extracted.47 Based on these results, the measurement properties of the model are acceptable.

5.3. Tests of the structural model

The standardized coefficients are provided in Fig. 2. The t and P values for each path in the

structural model are provided in Table 4. The results indicate significant direct relationships

among the following: (1) internal political efficacy and political trust; (2) internal political

efficacy and external political efficacy; (3) service quality and political trust; and (4) service

Table 2

Goodness of fit measures

Measure

2

v /(df)

Goodness of fit index (GFI)

Adjusted goodness of fit (AGFI)

Root mean squared residual (RMR)

Comparative fit index (CFI)

Normed fit index (NFI)

Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)

Estimate

Suggested

Conclusion

(56.04/48) = 1.167

0.936

0.896

0.084

0.986

0.911

0.037

b3.0

N0.90

N0.80

b0.05

N0.90

N0.90

b0.08

Acceptable

Acceptable

Acceptable

Not acceptable

Acceptable

Acceptable

Acceptable

729

Fig. 2. Estimated structural and measurement model.

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

730

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

Table 3

Assessment of reliability for constructs

Construct

No. of items

Composite reliability

Variance extracted

Internal political self-efficacy

Service quality

External political self-efficacy

Political trust

3

2

2

5

0.72

0.85

0.74

0.71

0.51

0.78

0.56

0.50

quality and external political efficacy. The squared multiple correlations (SMC) are provided in

Table 4. The estimated measurement and structural model is provided below in Fig. 2.

These results support three of the four hypotheses (H1a, H1b, and H2a). Both H1a and

H1b were supported strongly while H2a was not supported only marginally. The squared

multiple correlations (SMC) for political trust (0.42) and external political efficacy (0.40)

suggest that internal political efficacy and service quality explain a significant amount of the

variance of the dependent measures. The SMC for service quality is low (SMC = 0.04),

indicating that internal political efficacy explains only a small amount of the variance in

service quality.

6. Discussion and recommendations

Torkzadeh and Dhillon bluntly state that bThe ultimate questions[sic] about the success of

Internet commerce depends on how customers perceive its valueQ.52 However, their research

fails to address ongoing trust issues, limiting itself to transactional responses. Agarwal and

Venkatesh also fail to do so in presenting an instrument to assess a firms Web presence.53

Ngai and Wat, in their meta-analysis of e-commerce research, explicitly consider public

policy, but note that studies dealing with trust in public agencies are limited to those that

cover b. . .[the] assurance between what a trading partner says and actually doesQ.54 No

studies we know of consider the effect of e-government on political capital.

Table 4

Estimated path coefficients, t values, P values, and SMCs

Construct

Standardized path

coefficient (g)

t value

P value

Internal PSE Y Political trust

Internal PSE Y External PSE

Service quality Y Political trust

Service quality Y External PSE

Internal PSE Y Service quality

0.60

0.59

0.16

0.14

0.20

5.536

5.480

1.961

1.494

1.836

0.000

0.000

0.048

0.135

0.066

Squared multiple correlations

Political trust

External PSE

Service quality

0.43

0.40

0.04

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

731

Recent studies have taken broad measures of political trust34 and assessed the impact of IT

on trust. Other studies have examined the role of self-efficacy.55 However, no studies have

looked at the elements of trust that political efficacy embodies.

In some way, internal political efficacy is indicative of the power a citizen feels they have

over government after the election has taken place. This study shows that this construct, more so

than the overall perceived quality of the Web site, significantly influences and explains the

citizens overall trust in government, and ensuing belief that the government will be responsive.

The measure of trust in this survey looks at traditional performance metrics, namely, the

amount of perceived wastefulness, whether the government is perceived to be honest or

crooked, and the like. External political efficacy is analogous to this trust but examines it from

the individuals viewpoint of overall responsiveness, and the perception that the government

attends to the citizens needs.

This study suggests that in order to do so, the government needs to do much more than

create and maintain a good Web site and offer quality customer service. Governments

should engage individuals with high pre-existing levels of trust if they wish their online

efforts to succeed.

The term ddigital divideT has been used in reference to the gap between those that do

and do not have access to e-government. Normatively, it has been suggested that

governments need to ensure universal access for these initiatives to succeed.33 This study

would challenge this assumption, at least in the short term, and in the present political

climate. Those citizens most likely to gain in trust of the government as a result of

conducting an online transaction are those with high pre-existing levels of introspective

trust, not necessarily those who received a positive service experience. Put another way,

this research suggests that skeptics and cynics will remain so, irrespective of the quality

of service offered.

For policymakers, we suggest two things. First, we recommend a phased approach to

e-government, based on target market selection (e.g., citizens with high internal political

efficacy), and not necessarily on government product or service itself. In some cases, this

contravenes extant policy that has seen governments virtualize either those applications that

were most easily ported to the Internet, or those they perceived would provide the greatest

return on investment. A marketing and consumer-centric approach is suggested by this

research. In order to be successful, e-government must be seen to be successful. Those

applications with the greatest visibility and potential for elevating citizens involvement and

their internal political efficacy should be prioritized over those that promise value internally.

Secondly, it suggests that if elected officials and bureaucrats wish to migrate from

traditional channels of service to online transactions (thereby gaining some operational

savings), they should paradoxically not concentrate so much on building a positive Web

experience, as they should focus on building a trustworthy relationship with the electorate

outside the confines of the Internet.

Does e-government usage increase trust in government? This research offers a qualified

dyesT, and defines parameters that challenge conventional wisdom. E-government, in and of

itself, though necessary, is not sufficient to induce trust. Our research shows, rather, that

e-government intensifies existing levels of trust if these are positive, with no positive effect

732

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

on those whose trust is either neutral or negative. E-government is not a panacea for

unresponsive, distrusted government.

7. Limitations

There are three main limitations which constrain this research.

Firstly, the survey was posted online and employed a non-random convenience sample.

The survey is cross-sectional in nature so causality must be considered accordingly.

Collecting a significantly larger sample using an alternate survey modality and random

sampling methods would be an expensive endeavor. An online survey was selected

because it was free from geographical constraints; the Web enabled access to participants

across Canada, as is essential for this study of federal government. The online survey was

appropriate for collecting data from participants that had experience with e-government.

Even though a non-random sample was used, Table 1 demonstrates a fairly proportionate

representation of provinces in the survey sample. Census data from 2001 show a median

family income of $55,016.56 The average household income in this survey was $56,000.

A second limitation is that these findings should not be interpreted to be representative of

the Canadian voter because the survey was restricted to net-enabled citizens. Bonchek

reported higher levels of political efficacy among Internet users.57 Comparison with

educational attainment from census reveals above average levels of education in the sample.

Both biases in the sample could have directed some of the results of this study. Again, this

limitation can be addressed in future research.

Finally, the researchers are Canadian and the scope of this study has been limited to

the e-government experience and its relationship to citizen trust and political efficacy

with respect to the Canadian federal government. As such, the results should not be

extended to another country whose system of the government is not comparable.

Nevertheless, the main result of this study, namely, validation of the link between

political self-efficacy and trust, remains removed from the specifics of context. Future

research may support the validity and reliability of this link through replication in other

countries and contexts.

8. Conclusion

Governments around the world continue to invest in the Internet and have largely adopted

the mantra of service efficiency. This study challenges this by showing initial support for the

salience of political self-efficacy as it leads to trust in government.

Individuals with a priori trust in government, and correspondingly high levels of internal

self-efficacy, will have these reinforced through electronic interaction with their governments.

The reverse also holds: distrustful, low self-efficacy individuals will not increase their trust,

irrespective of the medium of interaction. The quality of interaction, while important, is

nonetheless secondary.

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

733

Therefore, if politicians aim to increase trust, they would be better served to focus on

non-Web-based courses of action. The bureaucracy, seeking efficiency in service delivery,

is better served to do the same, perhaps at the expense of improvements in Web site

performance.

For researchers, this study offers insights into declining trust on the part of the electorate

and new means to investigate and understand citizen trust.

Sir Francis Bacon wrote that bstates as great engines move slowlyQ.58 It is as true now, as it

was then. Governments have been slow to adopt e-government.33 This research partly shows

they have also been unclear and unfocused in their objectives and expectations. The ongoing

body of research into e-government, trust, and citizenry that this study adds to will hopefully

lead to manifest changes in both policy and practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Elaine Rioux and Audrey Vezina,

Contemporary Research Centre, Montreal, Canada, for translating the survey and to Simon

Fraser Universitys President Research Fund for supporting this research.

Notes and References

1. Rosenstone, S. J., & Hansen, M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in

America. New York7 Macmillan.

2. Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2001). Introduction: Studying the American peoples

attitudes toward government; When do Americans tend to be dissatisfied with government. In J. R. Hibbing, & E. Theiss-Morse (Eds.), What is it about government that

Americans dislike? (pp. 17). Cambridge7 Cambridge University Press.

3. Orren, G. (1997). Fall from Grace: The publics loss of faith in government. In J. S. Nye

(Ed.), Why people dont trust government (pp. 77107). Cambridge, MA7 Harvard

University Press.

4. Welch, E. W., & Hinnant, C. C. (2003, January). Internet use, transparency and

interactivity effects on trust in government. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences [main paper on accompanying CD-ROM].

5. Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (1995). Congress as public enemy. Cambridge7

Cambridge University Press.

6. Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Morin, R., Altman, D. E., Brodie, M., Brossard, M., et al.

(1997). Changing attitudes in America. In J. S. Nye (Eds.), Why people dont trust

government (pp. 205216). Cambridge, MA7 Harvard University Press.

7. Lawrence, R. Z. (1997). Is it really the economy stupid? In J. S. Nye (Ed.), Why people

dont trust government (pp. 111132). Cambridge, MA7 Harvard University Press.

8. Gartner Group (2000). Western Europe government sector: IT solution opportunities.

Market analysis. Stamford, CT7 Gartner.

734

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

9. Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. New York7 Wiley.

10. Hetherington, M. J. (1999). The effect of political trust on the presidential vote, 196896.

American Political Science Review, 93, 311326.

11. Hetherington, M. J., & Nugent, J. D. (1998). Explaining public support for devolution:

The role of political trust. In J. R. Hibbing, & E. Theiss-Morse (Eds.), What is it about

government that Americans dislike? (pp. 134151). Cambridge7 Cambridge University

Press.

12. Belanger, E., & Nadeau, R. (2002). Political trust and the vote in multiparty elections.

Paper prepared for delivery at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science

Association, Boston.

13. Thomas, C. W. (1998). Maintaining and restoring public trust in government agencies

and their employees. Administration and Society, 30(2), 166193.

14. Nye, J. S., & Zelikow, P. D. (1997). Conclusions: Reflections, conjectures and puzzles. In

J. S. Nye (Ed.), Why people dont trust government (pp. 253281). Cambridge, MA7

Harvard University Press.

15. Citrin, J., & Green, D. P. (1986). Presidential leadership and the resurgence of trust in

government. British Journal of Political Science, 16, 431453.

16. Hibbing, J. R., & Patterson, S. C. (1994). Public trust in the new parliaments of Central

and Eastern Europe. Political Studies, 42, 570592.

17. Mansbridge, J. (1997). Social and cultural causes of dissatisfaction with U.S. government. In J. S. Nye (Ed.), Why people dont trust government (pp. 133153). Cambridge,

MA7 Harvard University Press.

18. Inglehart, R. (1997). Postmaterialist values and the erosion of institutional authority. In J.

S. Nye (Ed.), Why people dont trust government (pp. 217236). Cambridge, MA7

Harvard University Press.

19. Bok, D. (1997). Measuring the performance of government. In Why People Dont Trust

Government. In J. S. Nye (Ed.), Why people dont trust government (pp. 5575).

Cambridge, MA7 Harvard University Press.

20. Nye, J. S., Jr. (1997). Introduction: The decline of confidence in government. In Why

People Dont Trust Government. In J. S. Nye, Jr. (Ed.), Why people dont trust

government (pp. 118). Cambridge, MA7 Harvard University Press.

21. Compeau, D., & Higgins, C. (1995). Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure

and initial test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189211.

22. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ7 Prentice-Hall.

23. van Duivenboden, H., & Lips, M. (2001). Taking citizens seriously: Applying

Hirschmans model to various practices of customer-oriented e-governance. Governing

Networks. European Group of Public Administration Yearbook (pp. 209 226).

Amsterdam7 IOS Press.

24. Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty. Cambridge, MA7 Harvard University

Press.

25. Abramson, P. R., & Aldrich, J. H. (1982). The decline of electoral participation in

America. American Political Science Review, 76(3), 502521.

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

735

26. Finkel, S. E. (1985). Reciprocal effects of participation and political efficacy: A panel

analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 29(4), 891913.

27. Roese, N. J. (1999). Are Canadians becoming less trusting of government? Northwestern

University mimeo.

28. Miller, A. H., & Borrelli, S. A. (1991). Confidence in Government during the 1980s.

American Politics Quarterly, 19, 147173.

29. Fountain, J. (2001). Building the virtual state: Information technology and institutional

change. Washington, DC7 Brookings Institution Press.

30. Brown, D. (1999). Information systems for improved performance management:

Development approaches in US public agencies. In R. Heeks (Ed.), Reinventing

government in the information age (pp. 321330). New York7 Routledge.

31. Anderson, K. (1999). Reengineering public sector organizations using information

technology. In R. Heeks (Ed.), Reinventing government in the information age

(pp. 312330). New York7 Routledge.

32. Northrup, T. A., & Thorson, S. J. (2003). The Web of governance and democratic

accountability. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences (HICCS 2003) [main paper on accompanying CD-ROM].

33. Accenture (2002). eGovernment leadership: Realizing the vision. New York7 Accenture.

34. Moon, M. J. (2003, January). Can IT help government to restore public trust?: Declining

public trust and potential prospects of IT in the public sector. Proceedings of the 36th

Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICCS 2003) [main paper

on accompanying CD-ROM].

35. Zucker, L. G. (1986). Production of trust: Institutional sources of economic structure,

18401920. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 8, 53111.

36. Brewer, E. C. (1898). Dictionary of phrase and fable. London7 Cassel and Company.

37. Craig, S., Niemi, R., & Shingles, R. (1987). American National Election Study 1988:

1987 Pilot Study. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Of Michigan, Inter-University

Consortium for Political Research.

38. Government of Canada. (2003). The shop on-line page. Retrieved June 15, 2003, from:

http://canada.gc.ca/form/commer_e.html

39. Government of Canada. (2003). Other Online Services. Retrieved June 15, 2003, from:

http://canada.gc.ca/form/e-servicesother_e.html

40. Devaraj, S., Fan, M., & Kohli, R. (2002). Antecedents of b2C channel satisfaction

and preference: Validation e-commerce metrics. Information Systems Research, 13(2),

316334.

41. Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. (1958). American National Election

Studies 1958 Post Election Study. University Of Michigan, Survey Research Center.

42. Converse, P., Meisel, J., Pinard, M., Regenstreif, P., & Schwartz, M. (1965). 1965

Canadian election study. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan, Inter-University

Consortium for Political Research.

43. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item

scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1),

240.

736

M. Parent et al. / Government Information Quarterly 22 (2005) 720736

44. Orlikowski, W. J., & Iacono, C. S. (2001). Research commentary: Desperately seeking

the bITQ in IT researchA call to theorizing the IT artifact. Information Systems

Research, 12(2), 121134.

45. Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies, analysis and antitrust implications: A

study in the economics of internal organization. New York7 Free Press.

46. Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M. (2000). Structural equation modeling and

regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association of

Information Systems, 4(5), 173.

47. Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data

analysis with readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ7 Prentice-Hall.

48. Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In

G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 321330). Mahwah,

NJ7 Erlbaum.

49. Segars, A. H., & Grover, V. (1993). Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness:

A confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Quarterly, 17(4), 517525.

50. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative methods for assessing model fit. In K.

A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (p. 136). Newbury

Park, CA7 Sage Publications.

51. Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. (2nd ed.). New York7 McGraw-Hill Book

Company.

52. Torkzadeh, G., & Dhillon, G. (2002). Measuring factors that influence the success of

Internet commerce. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 187204.

53. Agarwal, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2002). Assessing a firms Web presence: A heuristic

evaluation procedure for the measurement of usability. Information Systems Research,

13(2), 168186.

54. Ngai, E. W. T., & Wat, F. K. T. (2002). A literature review and classification scheme of

electronic commerce research. Information & Management, 39, 415429.

55. Hinnant, C. C., & Welch, E. W. (2003, January). Managerial capacity and digital

government in the States: Examining the link between self-efficacy and perceived

impacts of IT in public organizations. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences (HICCS 2003) [main paper on accompanying CD-ROM].

56. Statistics Canada. (2003). Income of Canadian Families [Catalogue Number

96F0030XIE2001014]. Retrieved September 14, 2003, from: http://www12.statcan.ca/

english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/inc/contents.cfm

57. Bonchek, M. S. (1997). From broadcast to Netcast: The Internet and the flow of political

information. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

58. Bacon, S. F. (1605). Advancement in learning: Book II. University of Oregon:

Renascence Editions. Retrieved June 5, 2003, from: http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/

~rbear/ren.htm

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Foodservice Wipes InfographicDocument1 paginăFoodservice Wipes Infographicalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Astragalus Root and Elderberry Fruit Extracts Enhance the IFN-β Stimulatory Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Murine-Derived Dendritic Cells PDFDocument10 paginiAstragalus Root and Elderberry Fruit Extracts Enhance the IFN-β Stimulatory Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Murine-Derived Dendritic Cells PDFalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Investment BankingDocument24 paginiIntroduction To Investment BankinglegonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Lectin From Elder (Sambucus Nigra L.) Bark PDFDocument7 paginiA Lectin From Elder (Sambucus Nigra L.) Bark PDFalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Elderberry PDFDocument5 paginiElderberry PDFalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- 30507-4 Surface ProductsDocument2 pagini30507-4 Surface Productsalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- !! Tony Buzan-Speed MemoryDocument163 pagini!! Tony Buzan-Speed Memorymaster_zankou2Încă nu există evaluări

- Engineering Structuring Investment Banking DealsDocument15 paginiEngineering Structuring Investment Banking Dealsalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Good Practices in The National Sustainable Development Strategies OECD CountriesDocument37 paginiGood Practices in The National Sustainable Development Strategies OECD Countriesalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Regional Policy: Operational Programme 'Development of The Competitiveness of The Bulgarian Economy'Document4 paginiRegional Policy: Operational Programme 'Development of The Competitiveness of The Bulgarian Economy'almirb7100% (1)

- Features of Fixed Income SecuritiesDocument9 paginiFeatures of Fixed Income Securitiesalmirb70% (1)

- U Said InvestmentDocument28 paginiU Said Investmentalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- FE Logistics04Document2 paginiFE Logistics04almirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Lexmark E332nDocument127 paginiLexmark E332npulmao_34Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Fall03Document4 paginiFinal Fall03almirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Miff 2010 2012 enDocument8 paginiMiff 2010 2012 enalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Pharma 2020 PWC ReportDocument32 paginiPharma 2020 PWC ReportBrand SynapseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ph2020 Tax Times FinalDocument28 paginiPh2020 Tax Times Finalalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Story of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence On American BusinessDocument0 paginiStory of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence On American BusinessRoberto FidalgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vision On Industry & World Till 2020Document52 paginiVision On Industry & World Till 2020kareemoyaboyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Model - ChallengeDocument24 paginiBusiness Model - ChallengeArun KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- FE04 Final SolsDocument3 paginiFE04 Final Solsalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Solutions Fall03Document3 paginiFinal Solutions Fall03almirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- FE Logistics04Document2 paginiFE Logistics04almirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Pajero Catalogue2Document13 paginiPajero Catalogue2almirb7100% (1)

- Mitsubishi OfferDocument1 paginăMitsubishi Offeralmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- Pajero Catalogue2Document13 paginiPajero Catalogue2almirb7100% (1)

- Dejan Kilibarda EWCM-2Document12 paginiDejan Kilibarda EWCM-2almirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- CRF150RB 2012 Press Information: CRF150RB, The Perfect Off-Road Competition Machines For Aspiring ChampionsDocument4 paginiCRF150RB 2012 Press Information: CRF150RB, The Perfect Off-Road Competition Machines For Aspiring Championsalmirb7Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- BROSUR 58th TEFLIN Conference 2g38ungDocument3 paginiBROSUR 58th TEFLIN Conference 2g38ungAngela IndrianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Starting List: Ifa World Armwrestling Championships 2019 Rumia, PolandDocument15 paginiStarting List: Ifa World Armwrestling Championships 2019 Rumia, PolandpnmrvvtlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upload.c Uhse002 3n12Document22 paginiUpload.c Uhse002 3n12رمزي العونيÎncă nu există evaluări

- Signaling Unobservable Product Ouality Through A Brand AllyDocument12 paginiSignaling Unobservable Product Ouality Through A Brand AllyalfareasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jaimini KarakasDocument3 paginiJaimini KarakasnmremalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of ChemistryDocument10 paginiHistory of ChemistryThamil AnbanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MythologyDocument9 paginiMythologyrensebastianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lakshmi Mantras To Chant For Success, Prosperity and WealthDocument5 paginiLakshmi Mantras To Chant For Success, Prosperity and WealthDurgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documented Essay About EmojisDocument8 paginiDocumented Essay About EmojisSweet MulanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The African Novel As A Strategy For Decolonization in Ama Ata Aidoo's 'Our Sister Killjoy'Document9 paginiThe African Novel As A Strategy For Decolonization in Ama Ata Aidoo's 'Our Sister Killjoy'EmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6au1 4scientificmethodDocument12 pagini6au1 4scientificmethodapi-333988042Încă nu există evaluări

- Leadership and Organisational Dynamics MBL921M Group Assignment 1 - ZIM0112ADocument25 paginiLeadership and Organisational Dynamics MBL921M Group Assignment 1 - ZIM0112ACourage ShoniwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 3c. Law & MoralityDocument18 paginiTopic 3c. Law & MoralityYuvanesh Kumar100% (1)

- Portfolio IntroductionDocument3 paginiPortfolio Introductionapi-272102596Încă nu există evaluări

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument7 paginiNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajKamÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGMT3006 Assessments2 CaseStudyReportDocument15 paginiMGMT3006 Assessments2 CaseStudyReportiiskandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brave New World VocabularyDocument6 paginiBrave New World VocabularyLouis Leon100% (1)

- (Applied Clinical Psychology) Robert P. Liberman, Eugenie G. Wheeler, Louis A. J. M. de Visser, Julie Kuehnel, Timothy Kuehnel (auth.) - Handbook of Marital Therapy_ A Positive Approach to Helping Tro.pdfDocument267 pagini(Applied Clinical Psychology) Robert P. Liberman, Eugenie G. Wheeler, Louis A. J. M. de Visser, Julie Kuehnel, Timothy Kuehnel (auth.) - Handbook of Marital Therapy_ A Positive Approach to Helping Tro.pdfLeonardoGiraldoSanchez100% (1)

- Kaisa Koskinen and Outi Paloposki. RetranslationDocument6 paginiKaisa Koskinen and Outi Paloposki. RetranslationMilagros Cardenes0% (1)

- Separate PeaceDocument28 paginiSeparate PeaceYosep Lee100% (2)

- Civic Welfare Training Service Program 2Document30 paginiCivic Welfare Training Service Program 2Glen Mangali100% (3)

- 150+ New World Order Globalist Agenda QuotesDocument59 pagini150+ New World Order Globalist Agenda Quoteskitty katÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bbe Minutes Sem III, 2012Document8 paginiBbe Minutes Sem III, 2012Sdrt YdvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manipulatives in Maths TechingDocument4 paginiManipulatives in Maths TechingerivickÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Discussion On The Names and Attributes of AllahDocument3 paginiA Discussion On The Names and Attributes of AllahmaryamÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Model Paper 3 emDocument15 paginiEnglish Model Paper 3 emReddy GmdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 03,04,05 - Intensity Transformation and Spatial Filtering PDFDocument46 paginiLecture 03,04,05 - Intensity Transformation and Spatial Filtering PDFVu Quang PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- GCWORLD Concept MapDocument1 paginăGCWORLD Concept MapMoses Gabriel ValledorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Christian in Complete ArmourDocument485 paginiThe Christian in Complete ArmourKen100% (2)

- AP Euro Syllabus 2017-2018Document17 paginiAP Euro Syllabus 2017-2018Armin Chicherin100% (1)