Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

1 s2.0 S0278239105003472 Main

Încărcat de

bortho10Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1 s2.0 S0278239105003472 Main

Încărcat de

bortho10Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

TECHNICAL NOTES

J Oral Maxillofac Surg

63:1048-1051, 2005

Methylmethacrylate as a Space

Maintainer in Mandibular

Reconstruction

N. M. Goodger, FRCS, FDS, DLORCS,*

J. Wang, DMD, MD, MPH, G. W. Smagalski, DDS, FACD,

and Bradford Hepworth, DDS, MD, MS

The use of alloplastic materials in oral and maxillofacial surgery is an accepted practice with the frequent utilization of bone substitutes, titanium plates,

mesh, and various onlay grafts. Methylmethacrylate

cement is an inert and well-tolerated material that has

been used for decades in orthopedic and neurosurgical procedures. Because it is moldable prior to

curing and easily trimmed, it is of particular use in

the reconstruction of awkwardly shaped defects,

such as those created by craniectomy. However, its

use has rarely been reported in the facial bones. We

have found methylmethacrylate to be a convenient

and practical material for the temporary space

maintenance of mandibular continuity defects following resection or for osseous defects secondary

to osteomyelitis. The material provides functional

stability, allows the intraoral soft tissue defects to

heal with minimal distortion from scarring, and

creates a soft tissue envelope into which bone

grafts can later be placed. The most significant

advantage to the patient is the maintenance of facial

*Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Kent and Canterbury

Hospital, Canterbury, United Kingdom.

Formerly, Resident, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA;

Currently, Private Practice, Sunnyvale, CA.

Formerly, Deputy Chief of Service, Department of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery, San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, and Assistant Clinical Professor, University of California, San

Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Formerly, Resident, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA;

Currently, Private Practice, Bainbridge Island, WA.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr Wang: Silicon Valley Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 877 W. Fremont Ave, E-1,

Sunnyvale, CA 94087; e-mail: drkvj@earthlink.net

2005 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

0278-2391/05/6307-0029$30.00/0

doi:10.1016/j.joms.2005.03.024

esthetics, with little extraoral evidence of soft tissue contraction.

Report of Cases

CASE 1

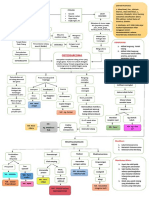

A 22-year-old man sustained a fracture of the mandibular

symphysis, failed to seek immediate treatment, and eventually developed osteomyelitis with a draining intraoral sinus

tract. Debridement of the mandibular fracture site was required, leaving a symphyseal trapezoidal defect 4 cm in

width inferiorly and 2 cm superiorly. A reconstruction plate

was applied to the mandible, a methylmethacrylate space

maintainer impregnated with 600 mg of clindamycin was

inserted into the defect region, and titanium screws were

placed to stabilize the acrylic. Postoperatively, the intraoral

communication healed without incident. Three months after the initial procedure, the patient was readmitted and the

mandible was approached through the previous submental

incision. A fibrous capsule was found encompassing the

methylmethacrylate space maintainer and the bone margins

were found to be well vascularized, after removal of a minor

amount of granulation tissue (Figs 1, 2). A corticocancellous

iliac crest bone graft was shaped, placed into the defect,

and retained with titanium screws. The surgical site was

reapproximated, and the patient healed without complication or esthetic compromise.

CASE 2

A 52-year-old man was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Service with a history of inadequate open

reduction and rigid fixation of bilateral body fractures of an

edentulous mandible. An actively draining orocutaneous

fistula was present in the right submandibular region and

had been present for 6 months. The left and right mandibular fracture sites were grossly mobile. The fractures were

debrided, hardware was removed, and the bilateral sites

were reconstructed with rib grafts fixed to a reconstruction

plate. Following this procedure, the patient developed adult

respiratory distress syndrome and was confined to the intensive care unit for 2 weeks. The bone graft on the right

side of the mandible became exposed intraorally and infection ensued. Four weeks after the initial procedure, the

patient was taken back to the operating room, and the

right-side bone graft was removed, the region was debrided,

and the intraoral wound was closed (Fig 3). A methylmethacrylate space maintainer impregnated with clindamy-

1048

1049

GOODGER ET AL

FIGURE 1. Case 1: Intraoperative picture of acrylic space maintainer

prior to bone graft.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

FIGURE 3. Case 2: Intraoperative appearance of defect after debridement of infected rib graft.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

CASE 3

cin and vancomycin was fabricated and secured to the

reconstruction plate (Fig 4). The extraoral wound was

closed in multiple layers. The patient made an excellent

postoperative recovery with no evidence of persisting infection or wound breakdown and then was referred for a

course of hyperbaric oxygen. Four months after placement

of the acrylic space maintainer, he was readmitted and the

methylmethacrylate was removed via an extraoral approach. A fibrous capsule was found to encompass the

acrylic, and after curetting a minor amount of granulation

tissue to expose well-vascularized bone ends, an iliac crest

corticocancellous bone graft was placed into the defect and

fixed to the reconstruction plate with titanium screws. The

decision was made to augment the contralateral bone graft

site with additional iliac crest bone at the same operative

procedure. The patient had an excellent postoperative recovery (Fig 5).

This patient is a 26-year-old, otherwise healthy man, who

originally presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Service with an expansile lesion of the mandible from the

right canine extending posteriorly to the condylar neck.

The lesion underwent biopsy and was found to be consistent with a cementifying fibroma. After thorough deliberation considering the extent of the lesion, the treatment

elected was a partial mandibular resection. The patient was

taken to the operating room for a resection of the right

mandible from the symphysis to within 2 cm of the condylar head. A reconstruction plate was placed from the condylar neck to the symphyseal region and then was removed

to facilitate the resection. The reconstruction plate was

then reapplied to the remaining mandibular sections, and

an alginate impression of the resected mandibular segment

FIGURE 2. Case 1: Intraoperative appearance of defect after removal of space maintainer.

FIGURE 4. Case 2: Intraoperative picture of placement of acrylic

space maintainer.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

1050

FIGURE 5. Case 2: Panoramic radiograph showing bone graft 1

month postsurgery.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

was obtained. Methylmethacrylate was then mixed, incorporating 600 mg of clindamycin, and was poured into the

negative alginate impression. The fabricated acrylic mandibular segment was inserted into the original resection site

and was affixed to the reconstruction plate with titanium

screws. The tissues were reapproximated, and the incision

was closed in multiple layers.

The patient healed without complication and was followed for 4 months. The esthetics were excellent, with

preservation of optimal facial contours. Secondary surgical

intervention was undertaken using iliac crest bone to reconstruct the mandibular defect. The surgical site was approached through the original submandibular scar to the

level of the reconstruction plate. An incision was made

along the lateral side of the plate, and the soft tissues were

reflected, revealing a well-encapsulated acrylic space maintainer. The acrylic was easily removed, leaving a well-defined pocket for the bone graft. No additional dissection

was required, although a minor amount of granulation tissue was noted at the bone resection ends. After curettage,

the bone ends were noted to be well vascularized, were

bleeding, and had the appearance of a fresh resection. Using

the methylmethacrylate space maintainer as a template, the

corticocancellous bone graft was shaped and contoured to

fit the defect and the plate. The fibrous capsule was scored

to encourage revascularization, and the bone graft was

inserted and fixed to the reconstruction plate with titanium

screws. The incision was reapproximated in the usual multilayer fashion. The patient had a benign postoperative

course. He was followed for 14 months (Fig 6) and then

referred for placement of dental implants to facilitate crown

and bridge reconstruction. He continues to have a good

occlusion and an excellent cosmetic result with minimal

evidence of surgical intervention.

METHYLMETHACRYLATE AS A SPACE MAINTAINER

air spaces.3 The material is easily molded prior to

polymerization and has excellent structural integrity.

It is now commonly used for temporary and permanent cranioplasty and as bone cement for alloplastic

joint replacement in orthopedic surgery.4 There are

several reports in the literature of methylmethacrylate

having been used in vertebral reconstruction and for

cosmetic alloplastic procedures.59 Govila10 reported

2 cases of mandibular reconstruction, and a larger

series of combined metal and acrylic implants was

published by Benoist11 with implants being fabricated

preoperatively.

Methylmethacrylate is reported to be well tolerated

by bone and soft tissues, and this has been confirmed

in our experience.4 16 The stabilized methylmethacrylate blocks allow the overlying oral mucosa and skin

to heal without delay or wound breakdown. A fibrous

capsule formed around the implant in each of the

patients reported here, but there was no significant

bone resorption and minimal evidence of granulation

tissue. During its exothermic reaction stage, it is important to irrigate the setting methylmethacrylate

with water or saline, or to remove it from bone

contact to avoid damage to the adjacent osseous

cells.17

The incidence of toxicity of methylmethacrylate is

low. There are reports of allergy to the monomer and

occasional reports of hypotension and cardiac arrest

following its use in joint surgery. However, there is a

possible correlation to these complications when

large amounts of unbound monomer are applied to a

large bone surface area or a plunger effect results in

fat embolism.7,18,19 Also, methylmethacrylate has

been reported to be detectable in both plasma and in

breast milk following joint surgery.20,21 Considering

Discussion

Heat-cured methylmethacrylate was originally used

in the early 1940s for facial prosthetics,1 and coldcured methylmethacrylate was reported to be initially

used in cranial reconstruction in 1941.2 The structure

of hardened methylmethacrylate cement is a composite of previously polymerized granules bound by recently polymerized monomer resulting in integrated

FIGURE 6. Case 3: Section from panoramic radiograph showing

integration of bone graft 1 year postsurgery.

Goodger et al. Methylmethacrylate as a Space Maintainer. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 2005.

GOODGER ET AL

its widespread use, methylmethacrylate has a low

incidence of associated complication.

The primary problem reported with methylmethacrylate implants in regions other than the facial bones

is infection,11,22,23 with rates near 20% at 1 to 2 years

postimplantation. These findings are supported by

Govila,10 but Benoist11 reports an infection rate of up

to 25% of cases in his series. In these situations,

nonvascularized bone grafts inevitably failed, yet

small defects may not warrant free vascularized bone

grafts such as fibula, scapula, or iliac crest with their

attendant morbidity. As the length of time of implantation increases, so does the incidence of infection.

No conclusive studies have reported short-term infection rates,16,22,23 but the risk can be limited in these

cases by the incorporation of antibiotics into the cement. It has been our experience that the implants

have not become infected even when placed in contaminated sites with associated intraoral fistula and

have permitted healing of the fistula (see patients 1

and 2). The first part of the technique described for

patients 1 and 2 has similarities to that of using antibiotic-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate beads in

the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis.24 27 In the

latter method, the mandible is usually approached by

an extraoral incision and the necrotic bone is debrided or resected. Mandibular form may be maintained with a reconstruction plate, and antibioticimpregnated methylmethacrylate beads are implanted

into the surgical site. The beads are removed 10 days

to 3 months later, and good results are reported.

However, our technique has the advantages of preservation of mandibular shape and facial soft tissue

contour, while creating an envelope into which a

bone graft can be placed when the implant is removed. This is performed 2 to 4 months after placement, minimizing the long-term infection risk and

allowing definitive bone grafting at the same procedure.

References

1. Munson FT, Heron DF: Facial reconstruction with acrylic resin.

Am J Surg 53:291, 1941

2. Kleinschmidt O: Plexiglas zur decking von schadellucken.

Chirurg 13:273, 1941

3. Cameron HU, Mills RH, Jackson RW, et al: The structure of

polymethylmethacrylate cement. Clin Orthop Rel Res 100:287,

1974

4. Robinson AC, ODwyer TP, Gullane PJ, et al: Anterior skull

defect reconstruction with methylmethacrylate. J Otolarygol

18:241, 1989

1051

5. Whitehill R, Cicoria AD, Hooper WE, et al: Posterior cervical

reconstruction with methyl methacrylate cement and wire: A

clinical review. J Neurosurg 68:576, 1988

6. Branch CL, Kelly DL, Davis CH Jr, et al: Fixation of fractures of

the lower cervical spine using methylmethacrylate and wire:

Technique and results in 99 patients. Neurosurgery 25:503,

1989

7. Rubin LR: Bone cement implantation, in Rubin LR (Ed):

Biomaterials in Reconstructive Surgery. St Louis, MO, CV

Mosby, 1983, p 452

8. Cheung LK, Samman N, Tideman H: The use of moldable

acrylic for restoration of the temporalis flap donor site. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 22:335, 1994

9. Schwartz AB, Kaufman P, Gluck M: Intraoral implantation of

methyl methacrylate for the restoration of facial contour in old

fractures of the malar complex. J Oral Surg 31:763, 1973

10. Govila A: Use of methyl methacrylate in bone reconstruction.

Br J Plast Surg 43:210, 1990

11. Benoist M: Experience with 220 cases of mandibular reconstruction. J Maxillofac Surg 6:40, 1978

12. van Mullem PJ, de Wijn JR: Bone and soft connective tissue

response to porous acrylic implants. J Craniomaxillofac Surg

16:99, 1988

13. Wellisz T, Lawrence M, Jazayeri MA, et al: The effects of

alloplastic implant onlays on bone in the rabbit mandible. Plast

Reconstr Surg 96:957, 1995

14. Worley RD: The experimental use of polymethyl methacrylate

implants in mandibular defects. J Oral Surg 31:170, 1973

15. Al-Sibahi A, Shanoon A: The use of soft polymethylmethacrylate

in the closure of oro-antral fistula. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40:

165, 1982

16. Cabanela ME, Coventry MB, Maccarty CS, et al: The fate of

patients with methylmethacrylate cranioplasty. J Bone Joint

Surg 54:278, 1972

17. Wykman AGM: Acetabular cement temperature in arthroplasty.

Acta Orthop Scand 63:543, 1992

18. Peebles DJ, Ellis RH, Stride SDK, et al: Cardiovascular effects of

methylmethacrylate cement. Br Med J 1:349, 1972

19. Milne IS: Hazards of acrylic bone cement. Anaesthesia 28:538,

1973

20. Gentil B, Paugam C, Wolf C, et al: Methylmethacrylate plasma

levels during total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res 287:

112, 1993

21. Hersh J, Bono JV, Padgett DE et al: Methyl methacrylate levels

in breast milk of a patient after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 10:91, 1995

22. Benzel EC, Thammavaram K, Kesterson L: The diagnosis of

infections associated with acrylic cranioplasties. Neuroradiology 32:151, 1990

23. Blum KS, Schneider SJ, Rosenthal AD: Methylmethacrylate cranioplasty in children: Long-term results. Pediatr Neurosurg

26:33, 1997

24. Merholtz ET, Haneke A: Gentamycin-PMMA kugeln als topische

therapie, in Wunderer S: Der Kieferchirurgie. Septische MundKiefer-Gesichtschirurgie, Vol 29. Stuttgart, Germany, Thieme,

1984, p 69

25. Grime PD, Bowerman JE, Weller PJ: Gentamicin impregnated

polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) beads in the treatment of

primary chronic osteomyelitis of the mandible. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 28:367, 1990

26. Dierks EJ, Potter BE: Treatment of an infected mandibular graft

using tobramycin-impregnated methylmethacrylate beads: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 50:1243, 1992

27. Chisholm BB, Lew D, Sadasivan K: The use of tobramycinimpregnated polymethylmethacrylate beads in the treatment of

osteomyelitis of the mandible: Report of three cases. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg 51:444, 1993

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- CABGDocument14 paginiCABGClaudette CayetanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orahex Oral SolutionDocument1 paginăOrahex Oral SolutionconanmarcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary Chinese Pulse Diagnosis A Modern InteDocument8 paginiContemporary Chinese Pulse Diagnosis A Modern InteAnkit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Total Gastrectomy ConsentDocument18 paginiTotal Gastrectomy ConsentTanyaNganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof Norhayati RMC KPJUCDocument18 paginiProf Norhayati RMC KPJUCtheskywlkrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conjoined Twins: Bioethics, Medicine and The Law: ViewpointDocument2 paginiConjoined Twins: Bioethics, Medicine and The Law: ViewpointSulistyawati WrimunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical Development of Psychiatric Social Work and Role of Psychiatric Social Worker in SocietyDocument9 paginiHistorical Development of Psychiatric Social Work and Role of Psychiatric Social Worker in SocietyZubair Latif100% (7)

- Communicable Disease SurveillanceDocument60 paginiCommunicable Disease SurveillanceAmeer MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's Your Coronavirus Insurance: You Have Made A Wise ChoiceDocument3 paginiHere's Your Coronavirus Insurance: You Have Made A Wise ChoiceAjay Kumar GumithiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Woc Osteosarcoma WidyaDocument1 paginăWoc Osteosarcoma WidyaWidya Agustiani0% (1)

- Decreased Urine Out PutDocument11 paginiDecreased Urine Out PutHila AmaliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barba D, Et Al, 2021Document103 paginiBarba D, Et Al, 2021Andrea QuillupanguiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hipaa FillableDocument2 paginiHipaa FillableRameezNatrajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Intra Natal Care 11aiDocument78 paginiEssential Intra Natal Care 11aiDr Ankush VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan CholecystectomyDocument2 paginiNursing Care Plan Cholecystectomyderic87% (23)

- GDMDocument30 paginiGDMCharlz ZipaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amputation and RehabilitationDocument4 paginiAmputation and RehabilitationimherestudyingÎncă nu există evaluări

- PhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)Document3 paginiPhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)CLAUDIA ELISABET BECERRA GONZALESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inseparable - Prospectus With 2021 BudgetDocument9 paginiInseparable - Prospectus With 2021 BudgetAralee HenighanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Type 2 Diabetes Recent StudiesDocument11 paginiSelf-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Type 2 Diabetes Recent StudiesSelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion To DismissDocument16 paginiMotion To DismissBasseemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infection Control Management Plan: PurposeDocument6 paginiInfection Control Management Plan: PurposeRekhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Most CommonsDocument80 paginiThe Most CommonsJmee8Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Report: Severe Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Pregnancy Mimicking HELLP SyndromeDocument5 paginiCase Report: Severe Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Pregnancy Mimicking HELLP SyndromeSuci Triana PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCMA113 FUNDA SKILL 1 Performing Medical HandwashingDocument3 paginiNCMA113 FUNDA SKILL 1 Performing Medical HandwashingJessoliver GalvezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal ReadingDocument3 paginiJournal ReadingRachelle Anne LetranÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Sample Content of The " PACING THE PACES Tips For Passing MRCP and Final MBBS"Document24 paginiA Brief Sample Content of The " PACING THE PACES Tips For Passing MRCP and Final MBBS"Woan Torng100% (2)

- You Exec - KPIs - 169 - BlueDocument14 paginiYou Exec - KPIs - 169 - BlueEssa SmjÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Mcqs Endondontic EmergencyDocument17 pagini2020 Mcqs Endondontic Emergencyareej alblowi100% (4)

- Genetic Disorders PDFDocument38 paginiGenetic Disorders PDFEllen Mae PrincipeÎncă nu există evaluări