Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

005-Urgent-JCombault - Presentation - Part 1

Încărcat de

Jimmy Villca SainzDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

005-Urgent-JCombault - Presentation - Part 1

Încărcat de

Jimmy Villca SainzDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

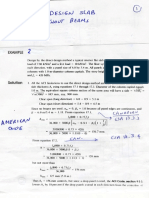

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Conceptual Design of Bridges

Short and Medium Span Bridges

Jacques COMBAULT

Consultant & Technical Advisor

Professor at the ENPC

President of IABSE

Jacques Combault, born in

1943, has been working as

bridge designer for more than

30 years, with Campenon

Bernard and GTM, both

being now companies of

VINCI (France). Recently

involved in major projects

abroad, he is currently

Consultant and Technical

advisor.

SUMMARY

The conceptual design of a bridge including foundations, supports and deck, has to be carried

out according to the required clearances, the selected materials and the possible construction

methods. This usually leads to applicable bridge types which are feasible and which can be

compared in terms of cost, aesthetics and durability.

The bases of the selection process, taking into account all the key parameters governing the

conceptual design of bridges, are detailed in the following pages. Several ways of classifying

bridges are proposed and finally discussed, for short and medium span bridges which have to

be made preferably continuous.

The necessary interaction between design and construction methods is emphasised as it lead

to the development of new structural concepts, in terms of materials (external prestressing),

combination of materials (corrugated steel webs, web trusses), prefabrication and assembly,

during the last 30 years.

KEYWORDS

Bridges, Classification, Concepts, Continuity, Design, Steel and Concrete, Reinforced and

Prestressed Concrete, Composite Structures.

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

CONTENTS

*******************

1.

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................- 3 -

2.

Classification of Bridges..........................................................................................................................- 3 -

3.

2.1.

Longitudinal anatomy of bridges .....................................................................................................- 3 -

2.2.

Materials ..........................................................................................................................................- 4 -

2.3.

Transversal anatomy of bridges.......................................................................................................- 5 -

2.4.

Construction Methods ......................................................................................................................- 6 -

Governing Parameters at the Conceptual Design Stage ......................................................................- 7 3.1.

From Discontinuity to Continuity ....................................................................................................- 7 -

3.2.

Discontinuous Bridges .....................................................................................................................- 7 3.2.1. Major Characteristics of Bridges with discontinuities ................................................................- 7 3.2.2. Advantages..................................................................................................................................- 8 3.2.3. Disadvantages .............................................................................................................................- 8 3.3.

Continuous Bridges..........................................................................................................................- 9 3.3.1. Theoritical Advantages ...............................................................................................................- 9 3.3.2. Practical Advantages .................................................................................................................- 10 3.3.3. Disadvantages ...........................................................................................................................- 11 4.

Short and Medium Span Bridges .........................................................................................................- 11 4.1.

Prestressed concrete bridges .........................................................................................................- 11 4.1.1. Construction and Design of Cast-in-Place Bridge Decks..........................................................- 11 4.1.2. Construction and Design of Incrementally launched Bridge Decks..........................................- 15 4.1.3. Prefabricated Concrete Decks ...................................................................................................- 16 4.2.

Steel-Concrete Composite Bridges ................................................................................................- 17 4.2.1. Construction and Design of classical Composite Bridges.........................................................- 18 4.2.2. Construction and Design of Steel Concrete Hybrid Bridges .....................................................- 18 4.3.

5.

Steel Bridges ..................................................................................................................................- 19 -

External Prestressing ............................................................................................................................- 19 5.1.

Practical advantages of external prestressing ...............................................................................- 20 5.1.1. Better concreting conditions......................................................................................................- 20 5.1.2. Elimination of threading and tensioning problems....................................................................- 20 5.1.3. Suppression of discontinuities in tendon profile .......................................................................- 21 5.1.4. Suppression of injection vents in the top slab ...........................................................................- 21 5.1.5. Possibility of a visual and mechanical checking of PT tendons ................................................- 21 5.1.6. Possibility of cable replacement or addition .............................................................................- 21 5.1.7. Possibility of making structure and PT tendons independent....................................................- 22 5.2.

Theoretical advantages of external prestressing............................................................................- 22 5.2.1. Elimination of ducts embedded in concrete ..............................................................................- 22 5.2.2. Simplicity of tendon profile ......................................................................................................- 23 5.2.3. Possibility of placing PT tendon anchorages at the best location..............................................- 23 5.2.4. Structural lightness....................................................................................................................- 23 5.2.5. Prestressing force efficiency .....................................................................................................- 23 5.2.6. Cost of external prestressing .....................................................................................................- 24 -

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-1-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.3.

Important Applications of external prestressing ............................................................................- 24 5.3.1. Structures considered as cast-in-Situ.........................................................................................- 24 5.3.2. Segmental bridges built according to the balanced cantilever method......................................- 26 5.3.3. New structures fully prestressed by external tendons ...............................................................- 26 5.4.

External prestressing technology...................................................................................................- 26 5.4.1. Cement-grouted non replaceable tendons .................................................................................- 27 5.4.2. Cement-grouted replaceable tendons ........................................................................................- 27 5.4.3. Replaceable tendons protected by a soft material .....................................................................- 27 5.4.4. Galvanised tendons ...................................................................................................................- 28 5.5.

Particular problems related to external prestressing ....................................................................- 28 -

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-2-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

1.

Introduction

The concept of a bridge has to be selected according to a certain number of specific

parameters which are related to the characteristics of the new link to be built and usually

specified by the representatives of the owner (State, Concessionaire or any relevant Private

Organisation); these characteristics are typically:

-

the location of the bridge

the purpose of the bridge (Motorway, Highway, Railway)

the importance of the bridge and the corresponding durability concerns

the completion date

Consequently, the Designer, as well as the Contractor at a later stage, has to take into account

the corresponding constraints prior to selecting the bridge type and construction methods:

The location of the bridge clearly leads to major inputs such as:

-

geographical and geotechnical conditions

crossing characteristics (valley, roads, railways, river) and corresponding span

distribution

possible natural and human made hazards (wind, earthquakes, impacts)

The purpose of the bridge generally leads to:

-

applicable specifications

relevant structural dimensions and details

The importance of the bridge and required durability finally lead to specify:

-

2.

the materials to be used

the way these materials have to be prepared and implemented

Classification of Bridges

Classification of bridges may be achieved in many ways:

2.1.

according to how they look like longitudinally, or transversally

according to the materials to be used or the way they are going to be built

Longitudinal anatomy of bridges

There are basically two types of structural elements [1]:

-

those transferring forces acting upon them by axial forces

those elements resisting forces acting on them by bending

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-3-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

When judiciously combined (Figure 1), these two structural elements lead to five types of

bridges:

-

inclined leg bridges and arches, when axial force is compression

girder bridges

cable stayed and suspension bridges, where axial force is tension

Axial Compression

Bending

Axial Tension

Figure 1 : Structural components are basically resisting axial forces and bending

Judiciously combined, they give rise to five types of Bridges

It is worth mentioning that must of them have been invented by nature and progressively

investigated, understood and improved by Engineers. It has also to be noticed that girders are

indeed resisting thanks to the simultaneous action of tension and compression elements, either

visible (trusses) or non visible (beams) and might therefore be considered as a combination of

both.

2.2.

Materials

During the last two hundred years, a number of new materials have been created. Steel and

concrete replaced wood and stone while structures and forms were simultaneously adapted to

the evolution of resistant materials:

-

Concrete is heavy and non resisting to tensile forces but it is definitely recognised as

being well adapted to compression members [5]

Steel is resisting high compressive and tensile stresses and therefore relatively light.

Meanwhile, as slender elements are subject to buckling, it is preferably used to form

tension members or cables

Performances of both steel and concrete have been considerably improved during the last

twenty years in such a way that structures which would have not been possible in the past

have become feasible.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-4-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

2.3.

Transversal anatomy of bridges

Depending on the materials or combination of materials being used, typical cross sections of

bridges (Figure 2) are classified as slabs (concrete), beams and box girders (open or not) [2].

Concrete

Composite

Steel

Slab

Embedded Steel Beams

I Beam

T Girders

Open Box Girders

Box Girders

Figure 2 : Typical Cross-Sections of Bridge Decks

Most of the components of these transversal structures essentially resist to loads by bending.

For a given crossing, applicable cross sections are selected according to span length,

structural type, deck width, available materials and construction methods. Box girders are

generally preferred for curved bridges or long spans requiring aerodynamic shaping and

torsional stiffness (Figure 3).

While concrete structures appears to be heavy and steel structures to be light, it must be

recognised that fabrication of steel structures is much more sophisticated as many stiffeners

have to be provided to eliminate any buckling or plate out-of-plane risk.

This is the reason why, when possible, the association of steel and concrete in a composite

cross-section highly simplifies the steel design and fabrication.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-5-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Figure 3 : Concrete and Steel Box-Girders (Right) Steel Frame of a Composite Deck (Left)

2.4.

Construction Methods

Due to the necessary connection between cast-in-situ foundations and pier shafts, bridge

supports are generally cast in place.

Concrete deck structures are either cast in place (i.e. at their final location), or built in a

practical place prior to being moved to their final location, or prefabricated in many pieces

then transported and assembled at their final location. This leads to classify the construction

methods as follows (Table 1):

- CAST-IN-SITU METHODS

- DISPLACEMENT METHODS

- PREFABRICATION

- Forms on Scaffolding

- Forms on Temporary Supports - Span-by-Span

- Self supported Forms.

- Balanced Cantilever Erection

- Longitudinal Translation (Incremental Launch)

- Translation - Transversal Translation

- Vertical Translation - Around a Vertical Axis

..

- Rotation

- Around Horizontal Axis

- Beams placed with cranes or launching gantries

- Short Line - Balanced Cantilever Erection

- Box Girders

- Progressive Placing

- Long Line - Span-by-Span Construction

Table 1 : Classification of Concrete Structures according to Construction Methods

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-6-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Steel deck components are generally prepared in a factory before being delivered and

assembled on the construction site. Incremental launching as well as balanced cantilever

assembly are the most common placing methods in use for the construction of steel decks.

Concrete slab of steel concrete composite bridge decks are either easily cast in place or made

of prefabricated slab panels.

3.

Governing Parameters at the Conceptual Design Stage

In relation with the site characteristics, the materials to be used, the selected longitudinal and

transversal concept of the bridge and the applicable construction methods, which have to be

selected as a whole at the conceptual design stage, the deck structure is more and more

commonly made continuous.

Continuity is applicable to all kind of bridges and a lot of examples can be found in the past

and recent years to emphasise this powerful concept.

Short and medium spans made of classical constant depth girders, all being either made of

concrete, steel or combination of both, show many spectacular structures which are good

examples of continuous bridge decks and the success of these bridges has to be associated

with several main advantages.

As it can be seen, from some examples, continuous structures are generally nice and

continuity leads undoubtedly to a certain standard in terms of aesthetics and comfort for users.

But continuity means also many theoretical and practical advantages which can be

appreciated through simple calculations or developments of a wide range of construction

methods. In addition to that the combination of modern construction methods and of a

continuous external prestressing can lead to a fine tuning of the permanent forces to resist the

traffic loading.

3.1.

From Discontinuity to Continuity

It is not in fact possible to separate clearly all the key parameters governing the choice which

could be made, with regard to continuity or discontinuity, as they are many and interfering all

together; but some characteristics might be considered as generally representative of one

technology with regard to the other one.

3.2.

Discontinuous Bridges

Discontinuity appears to be, first, the simplest concept. Basically, discontinuity comes from

the quite simple and natural idea of placing beams simply supported at both ends one against

each other to span small consecutive gaps on a given width. No other system seems to be that

simple, both from a design and construction point of view, whatever the material used to

make the beams is.

3.2.1. Major Characteristics of Bridges with discontinuities

Although it could be possible to connect longitudinally successive beams of any shape, I

shape for beams made of steel or concrete to support a slab, seems to be a major characteristic

of bridge deck with no continuity.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-7-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

The way the beams are supported is another major characteristic. Simple supports at both

ends is very common although bridges consisting of cantilevering boxes built-in the piers,

either made of steel or concrete, have been built intensively in several countries for many

years in order to accommodate span length or to use the very efficient balanced cantilever

erection method to build bridges.

These various corresponding static schemes can be considered as the different stages which

have been necessary in bridge engineering to move from the simple initial concept to the

more sophisticated concept of continuous structures.

3.2.2. Advantages

It is a fact that statically determined

structures are basically discontinuous but

the calculations to be carried out are easy

and therefore attractive.

Simple beams are not sensitive to

imposed displacements, mainly to

differential settlements or temperature

gradients, and were probably preferred to

any other solution when engineers did not

master foundation design.

In addition to that, placing parallel

girders can be easily managed by

adjusting the number of girders to cover

the required width and therefore the

weight of the girders. As long as the

lifting and placing equipment was not as

powerful as it can be today, this was a

serious advantage which allowed solving

all problems of interaction between

design and construction.

Figure 4 : The Don Muang Tollway Viaduct (Bangkok)

3.2.3. Disadvantages

A lot of disadvantages could be identified by a rigorous comparison with continuous bridges.

Nevertheless, it can be stated first that simply supported bridges do not allow long spans.

Secondly when the beams are long a heavy launching device is needed.

Due to the number of beams, piers have to be wide or to consist of a shaft topped by a big

cross beam (Figure 4).

In terms of deflection, these beams, if made of concrete, are very sensible to creep and the

only way to avoid that is to implement a partial prestressing equilibrating the dead weight

only.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-8-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Although discontinuity can be overcome by a partial continuity of the beams at the level of

the top slab the use of beams leads to a large number of joints which are a weak point of these

structures in terms of comfort.

Finally, aesthetics of such structures is generally considered to be poor even if it can be

improved by designing the piers in an elegant way.

3.3.

Continuous Bridges

Continuity does not mean necessarily monolithism and does not apply to all types of cross

sections.

If typical concrete I or U beams are used, it seems unnecessary and not logical to make them

continuous as long as it requires sophisticated or heavy connection concepts (big cross beam

resting on bearings). Then, box girders will be the only type of concrete deck considered

hereafter.

Under certain circumstances (piers high enough, flexible supports) the concrete structures can

be made monolithic, combining then several advantages which will be identified later.

Of course, these remarks do not apply to steel or composite bridge decks which can be

economically designed using I beams (of constant or variable depth) and which cannot be

made connected rigidly to the piers.

3.3.1. Theoretical Advantages

It is not useless to mention once more the considerable advantages such bridges demonstrate

in terms of aesthetic and comfort as long as the problem of creep in continuous concrete

structures is well appreciated.

Generally speaking, continuity allows for a good distribution of stresses in the bridge decks

whatever the construction scheme is.

3,5

3,0

cantilever M

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

M continuous spans

0,5

0,0

-0,4

-0,2

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,0

1,2

1,4

-0,5

-1,0

M all spans loaded

-1,5

M one span loaded

-2,0

-2,5

-3,0

simple span M

-3,5

Figure 5 : Comparison of the Bending Moments generated in discontinuous and continuous spans

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

-9-

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

The diagram of permanent bending moments generated in a multi-span deck shows how these

bending moments are well distributed all along the span length if the combination of

construction methods and prestressing has been chosen to get a fine tuning of the permanent

forces to resist the traffic loading (Figure 5).

At Serviceability Limit States, the effects of traffic loads are also less severe than for a simply

supported span even if the most unfavourable bending moments at piers are generated by the

loading of two consecutive spans and if negative moments can be generated at mid-span.

Nevertheless, on the contrary of what happens in simply supported spans, which are governed

by the only behaviour of the cross section located at mid-span under a single traffic loading,

the behaviour of continuous bridge deck depends on a lot of parameters as long as the most

unfavourable load cases are absolutely different for each governing cross sections.

This fundamental property has several important consequences. The major one concerns the

Ultimate Limit States as it is clear that 3 plastic hinges have to develop for the failure of a

typical span of a continuous deck when one hinge only is critical for a simply supported deck.

The most unfavourable effects being produced by quite different loading combination, it is a

fact that the safety factor which can be reached at ultimate limit states on such a continuous

bridge is much higher than for a simply supported span.

This list of advantages would not be complete if pier-deck continuity was not mentioned.

The fact is that, in deep valleys, when pier shaft are high and flexible, the deck can be built in

the piers making then the piers participating efficiently to the general behaviour of the

structure and therefore to the strength of the deck.

3.3.2. Practical Advantages

Practical advantages of continuity are either direct consequences of theoretical ones (as for

examples aesthetics (Figure 6), comfort, and economy) or the result of the wide variety of

construction methods which can be imagined in conjunction with the use of a modern

prestressing tendon layout.

Figure 6 : Continuous bridges are beautiful and comfortable La Gruyere Bridge (Switzerland)

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 10 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

3.3.3. Disadvantages

The main disadvantage is theoretical. Strain constraint, which is a pure result of continuity,

unavoidably leads to significant bending moments under temperature gradients, these bending

moments being unfavourable at mid-span, as they are cumulating with the effects of other

loads. This is the reason why continuity of simple beams is not easy to do, as temperature

gradients are generating tremendous positive bending moments when positive permanent

bending moments are greatly reduced to a minimum which does not allow for an efficient

tendon layout.

In addition, such structures are clearly sensitive to differential settlements and creep of

concrete which have then to be taken into account with a high factor of safety.

4.

Short and Medium Span Bridges

According to the above, classical short and medium span bridges are therefore made

preferably continuous, using either concrete or steel concrete composite structures. As a

result, the cross section of such bridges has to be designed for resisting negative bending

moments at support locations and the deck generally consists of an open box girder when

spans are short enough or of a box girder for longer spans.

4.1.

Prestressed concrete bridges

Any construction method mentioned in Table 1 is applicable to prestressed short and medium

span concrete bridge decks.

4.1.1. Construction and Design of Cast-in-Place Bridge Decks

When the bridge is located in a convenient site with a flat area which is not congested by

roads or railways, when it does not have to cross water and when the soil has a good bearing

capacity, the simplest way to build the bridge is to cast it span by span, in forms supported by

scaffoldings or temporary supports, according to the sketch of Figure 7.

Figure 7 : An easy way to build short span bridges in a convenient site

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 11 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Construction in Self-Supported Forms

But as soon as the bridge must span a congested area, or a stretch of water, the best way to

build a multi span bridge with short spans is to use self-launching equipment consisting of a

steel structure supporting the forms as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 : Construction of short span concrete bridges using self launching equipment

As the launching equipment and the associated forms are generally complicated and heavy, it

makes sense to use this erection process for small spans (30 to 40 meters long) in conjunction

with an open box design of the deck.

Figure 9 : Self-launching equipment used for the construction of La Gruyere Bridge

Depending on the required width of the crossing, the span-to-depth ratio of the deck will be

then in the range 18 20 and applicable cross sections of such continuous open boxes will be

as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 : Typical Cross Sections of Decks cast in place in a Launching Equipment

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 12 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Spans are generally cast in sections located in between the so-called zero-moment points.

Under these conditions and taking into account creep effects, the final distribution of the

permanent bending moments in the bridge is not far from what it would be if the bridge was

cast in one sequence only on a full length scaffolding, the PT tendon layout being adapted to

all construction sequences and therefore as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11 : Typical PT tendon layout for a span-by-span cast-in-Situ Bridge Deck

Of course, the construction of the deck using a self-launching formwork is also applicable to

40 to 60 meter long spans in conjunction with a box design, but it has to be emphasised that

other and more efficient construction methods (Cf. 4.1.2) are preferred for practical reasons.

Balanced Cantilever Construction

Indeed, when spans of the bridge are longer than 60 meters, cast-in-situ decks have to be built

according to the basic principles of the balanced cantilever method which is commonly used

for erecting short and medium span bridges all around the world while other construction

methods are not applicable.

Figure 12 : Construction stages of the Balanced Cantilever method

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 13 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Using form travellers, the bridge deck construction progresses symmetrically from the piers

(Figure 12) in short sections (segments), typically 3.00 to 4.50 m long, up to the middle of

each span, the successive balanced cantilevers built that way being finally made continuous.

Form travellers (Figure 13) are installed on starting deck sections (pier segment) which have

to be temporarily fixed to the piers to resist the unbalanced loads during construction.

Figure 13 : Principles and examples of classical Form Travellers

The high efficiency and success of the method is not only due to the fact that it is possible to

build long enough spans made of a variable depth box girder; it is also due to the fact that:

-

distributed loads generated by the dead weight of variable depth cantilever are the

most significant where they are the less unfavourable;

negative bending moments, which are drained towards the pier axis, are fully resisted

by the highest and strongest sections of the deck (Figure 14);

extreme

positive

bending

moments generated by the dead

weight (creep effects) are

consequently greatly reduced, as

well as bending moments

generated by live loads in tallest

sections at mid span which are

less than what they would be in

constant depth girders (stiffening

effect of the deck near piers);

available PT units make it

possible to finely tune the

At Mid Span

At Piers

prestressing force distribution to

the bending moment distribution.

Figure 14 : Typical cross-sections of a variable depth box

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 14 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Variable depth girders therefore

are well adapted to the design

of continuous bridges; in

addition, when associated to

gracefully shaped piers, they

generally lead to extremely

elegant medium span bridges.

Figure 15 : Elegance of Bridges made of a variable depth Box-Girders

For such variable depth girders, the PT tendon layout consists of three families of tendons:

-

the balanced cantilever tendons;

the closure tendons;

the continuity tendons;

Figure 16 : Typical PT tendon layout of a span built according to balanced cantilever method

4.1.2. Construction and Design of Incrementally launched Bridge Decks

Another way to build concrete short and medium span bridge decks is to use an incremental

launching method, which is recognised to be an easiest and simplest way to perform the

necessary construction tasks in the best economical and working conditions as:

-

The site installations (offices,

cranes, materials, batching plant,

forms) are concentrated at the most

convenient location and does not

normally need to be moved during

the whole construction process of

the deck;

Specific equipment to be used is

simple;

Major works are carried out at

ground level behind the abutments;

Casting operations and launching

phases are organised to fit with the

required construction time.

Figure 17 : Launching methods versus span lengths

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 15 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

The method is flexible enough to offer several possibilities according to span lengths of the

bridge (Figure 17).

Figure 18 : Incremental launching method - Equipment and sequences commonly used

The necessary equipment (Figure 18) mainly

consists of:

-

A casting bed including the necessary

forms;

A steel launching nose (or a temporary

stay cable system);

The necessary sets of temporary

sliding bearings to be installed at each

pier for launching sequences (Figure

19;

A translation device.

Figure 19 : Sliding devices - Details

The span-to-depth ratio of incrementally launched bridge decks is usually in the range 16

18. As any section of typical spans has to resist negative bending moments and high shear

stresses when reaching a pier and positive bending when going through mid span, the PT

tendon layout is mainly made of

straight cables and the deck

preferably consist of a constant

depth box (Figure 20) with thick

webs,

though

additional

deviated PT tendons are

generally added after completion

of the deck for counteracting

dead loads as much as possible.

Figure 20 : Typical cross-section of an incrementally launch bridge

4.1.3. Prefabricated Concrete Decks

Prefabrication of concrete decks will be mentioned here for short span bridges made of simply

supported beams, as the number of bridges designed and built that way has been considerable.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 16 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Prefabrication of concrete bridge decks made of box girders opened up so many new horizons

to Engineers that it will be extensively developed in a separate part of this document

specifically addressing this important topic.

Indeed, the idea of prefabricating concrete beams to build concrete structures has been

developed since the very beginning as a consequence of the new possibilities offered by

prestressing technology. Though discontinuous bridges were previously criticised, it must be

recognised that this construction method has many advantages from a practical point of view:

-

Beams are all the same design and simply fabricated on site or in a factory in good

conditions

They are easily transportable and quickly erected using either cranes or self-launching

equipment

Any deck width may be accommodated with an adequate number of beams

Figure 21 : Precast Beams - Typical Beam arrangement and PT tendon layout

Typical applicable cross-sections of bridge deck made of precast beams and PT tendon layout

of a prestressed concrete unit are shown in Figure 21.

4.2.

Steel-Concrete Composite Bridges

Short and medium span bridges are made more and more economical and easy to build by the

association of steel and concrete and the combination of their major characteristics.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 17 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

4.2.1. Construction and Design of classical Composite Bridges

There are different ways of associating steel and concrete in the design of bridges, the most

commonly used resulting of the connection of a concrete slab to a steel structure and leading

to typical cross sections as shown in Figure 2.

Actually, such an association has the following advantages:

-

Composite deck structures are lighter than concrete deck structures and foundation

cost is consequently reduced

Unless subject to abnormal loads, steel structures are generally made simple and

consisting of twin I-girders braced at a regular spacing

Steel structures are easily and quickly erected by using incremental launching

Either cast in place or made of precast panels, reinforced concrete slab is easily built

when steel structure has been launched

In addition, the assembly yard and the launching equipment of the steel structure, as well as

the forms of the concrete slab, are very simple (Figure 22).

Figure 22 : Steel structure, launching bearings and cast-in-situ concrete forms

This family of composite bridges is well adapted to spans 50 to 80 meters long with a 25 to 30

span length-to-depth ratio.

4.2.2. Construction and Design of Steel Concrete Hybrid Bridges

Though the concept of hybrid construction is essentially beneficial in the field of long span

bridges which will be developed in the third part of this document, it also applies to the design

of medium span bridges under certain conditions. In fact, the basic principle of the concept is

to use the right material at the right place; i.e. concrete where weight is required and not too

expensive, steel where weight is detrimental and placing of large components is easy.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 18 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

As an example of such a powerful concept, Figure 23 shows the most important erection

stages of the main span of a bridge over a large river for which delivery, hoisting and final

placing of an orthotropic steel box was easy, while construction of the concrete deck of

traditional short span approaches was cost effective.

Figure 23 : The Chevire Bridge Delivery and placing of the orthotropic box girder of the main span

4.3.

Steel Bridges

Despite progress made in the fabrication and protection techniques of orthotropic steel boxes,

decks of short and medium span bridges are generally not made of steel.

Nevertheless and as previously mentioned, any construction method is applicable to the deck

erection of such bridges, should steel would be required for any reason, and some of these

construction methods (incremental launching, cantilever erection) are extensively used for the

erection of long span bridge decks preferably made of steel.

5.

External Prestressing

The idea of external prestressing is not new. Indeed, several bridges were built in France with

tendons outside the concrete as early as 1950 but, due to the lack of an available technology at

that time, these tendons were in a really bad shape 30 years later.

External tendons were then only used when they were temporary (cantilever stability,

blocking pin joints, incremental launching ...) or when there was no other solution (Repair and

upgrading of existing structures) and more than 20 years had gone by before this simple idea

was brought back into use.

Experience gained with the repair of existing structures, competition between concrete

structures and steel-concrete composite structures, development of new structural concepts as

well as new construction methods, lead Structural Engineers to revisit and develop the

attractive idea of external prestressing which opened up new horizons [3].

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 19 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.1.

Practical advantages of external prestressing

Henceforth, the elimination of tendons which were habitually located inside the concrete (at

gussets or spread out in the webs) constitutes a large improvement in the quality of the

structure.

5.1.1. Better concreting conditions

Ducts placed in the concrete at gussets or in the webs (Figure 24), i.e. at strategic points in the

structure, often create a barrier across which the concrete must be poured (especially when

ducts overlap one another because of deviations). Eliminating this obstacle makes good

concreting much easier.

5.1.2. Elimination of threading and tensioning problems

The risks previously mentioned and particular

construction methods sometimes lead to

problems concerning:

-

Cable threading which may be hindered

by excessive friction coefficients or

obstructions in the ducts themselves

Tensioning operations due to repeated

strand breakages at abrupt changes of

slope near anchorages.

In both cases, these mishaps are usually

provoked by the fall of fresh concrete on to the

tendon groups, by vibrator impact on the ducts

and bad jointing between ducts and

anchorages. Often respect of good practice at

the design stage and particular care during

construction will reduce these problems where

as external prestressing will eliminate them

entirely.

Figure 24 : Illustration of concreting conditions

(Around bonded tendons)

Figure 25 : Angles at duct connections and anchorages leading to excessive friction or wire failure

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 20 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.1.3. Suppression of discontinuities in tendon profile

Prestressing inside the concrete also means a certain multiplication of the number of

anchorages spread throughout the length of the structure. This inevitably leads to abrupt

discontinuities in prestressing, to awkward formwork details (for example, short and

projecting anchorage blisters) and as a rule generally bad overall conception. The concreting

phases must be adapted to the tendon layout and tensioning operations are often numerous.

In this respect external prestressing is much more practical for the designer (Figure 26).

Figure 26 : Continuous PT tendon profile

(Only connected to the structure at pier and deviation diaphragms)

5.1.4. Suppression of injection vents in the top slab

When properly conceived, external prestressing only comprises tendons whose high point is

near the anchorages in the counter-curve.

This particularity, plus the need for continuous water tight ducts, eliminates the possibility of

intercommunication and simplifies grouting procedure and eliminates injection tubes

embedded in the concrete emerging on to the road surface.

5.1.5. Possibility of a visual and mechanical checking of PT tendons

It is a great improvement with respect to conventional prestressing to be able to visually

check the most part of all the tendons as well as duct joints, grouting operations, the quality of

grouting and finally, under certain conditions (according to the method used), the tensile

stress in the tendons during the life of the structure.

5.1.6. Possibility of cable replacement or addition

Furthermore, although not absolutely essential, external prestressing can be designed to be

replaceable and even reinforced if necessary as long as this possibility is considered in

advance.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 21 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.1.7. Possibility of making structure and PT tendons independent

Finally, when tendons are arranged outside the concrete, the extraordinary independence

between structures and prestressing opens up new horizons, which engineers are beginning to

master (Figure 27). For although the simultaneity of the important steps accomplished during

the last five years prevent a dear differentiation of the different causes of the progress made,

one thing is certain: the idea of external prestressing was the catalyser for a boom in the

geometry and materials (or combinations of materials) which could be associated with

prestressing [4].

Figure 27 : Illustration of the independence of the PT tendons with regards to the deck structure

5.2.

Theoretical advantages of external prestressing

External prestressing improves, therefore, the general quality of prestressed structures; these

advantages are well attuned to the present day trends towards safety, elimination of defects

and the option of easy and permanent checking.

Nevertheless safety and durability are also the result of the perfect operation of the structures

designed and the contribution to this made by the modern technology of external prestressing

is considerable.

5.2.1. Elimination of ducts embedded in concrete

Generally speaking, the elimination of ducts in the concrete reduces the risk of local

weakening of the cross-section at locations where concreting is critical and where forces such

as transverse bending moments, general and local shear inevitably accumulate.

The suppression of "holes" corresponding to the duct passage along a section throughout the

web height puts aside any controversy about web resistance to shear forces. In the absence of

such voids during construction and of the heterogeneous state (tendon + grout + duct) in

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 22 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

service it is certain that the compression paths are not deviated and consequently do not

become fragile.

In other words, in all important cross-sectional zones (gussets, webs, slabs) external

prestressing improves the structural resistance to all the forces applied to it and it does with

less materials.

5.2.2. Simplicity of tendon profile

External prestressing tendons present the advantage of being less deviated. The tendon profile

is simple and easy to respect. It has many straight sections for which friction coefficients are

inexistent because duct wobble is impossible. Recent technological developments eliminate

the risk of alignment errors in deviation saddles and anchorage blisters. The curvature friction

coefficient, which depends closely upon the technology employed, can be much lower than

that normally used for the calculation of friction losses and the final prestressing forces in

external prestressing tendons are much higher than those obtained in classical internal

prestressing tendons.

5.2.3. Possibility of placing PT tendon anchorages at the best location

Here again, the profile simplicity, which is the result of geometrical and physical analysis,

leads to a concentration of anchorages in the diaphragms normally provided at piers and

abutments. These diaphragms are naturally massive and clearly adapted to receive the large

forces applied by the anchorages.

This disposition is one of the most important advantages of external prestressing (in spite of

its apparent discretion) because it eliminates the anchorages spread out along the total length

of the structure which are at the origin of high local tensile and shear stresses in areas where

the general forces are not sufficient to provide the required resistance (continuity cables in the

bottom slab for example).

5.2.4. Structural lightness

The logical consequence of the advantages cited above and therefore of the use of external

prestressing is the dead weight saving. For equal structural resistance it is possible to reduce

the web thickness, gusset volumes and, as will be seen later, the bottom slab thickness without

weakening the cross-section.

On the contrary, the homogeneous character of all the cross-sections throughout the structure

is an additional advantage. The load reduction due to lower dead weight is favourable both

during service and construction.

5.2.5. Prestressing force efficiency

The improved quality of the prestressing and the reduced cross-sectional area lead to an

increase in the stresses resulting from the axial prestressing force.

These factors compensate for the loss of eccentricity which can be encountered with external

prestressing and permit a better exploitation of certain construction methods at the time of

conception.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 23 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.2.6. Cost of external prestressing

Finally, for the same quality, external prestressing is in principal less expensive than classical

prestressing.

Its main advantage is in eliminating repeated installation, adjustment and fixing operations.

However, these cost differences are difficult to appreciate and frequently hidden by the

technological improvements in the field of external prestressing which are being

progressively developed by engineers during the conception of future projects.

As a matter of fact, the economy of external prestressing is not unanimously recognised: but

when it seems to be more expensive than traditional prestressing it must be remembered that

it is dismountable and therefore interchangeable, it is continuous and hides no tricks

concerning the distribution of forces in the structure.

5.3.

Important Applications of external prestressing

It was towards the latter part of the 1970's that the first spectacular applications of external

prestressing, combined with innovative construction methods, were to be seen. In the

meantime, the need for repairing and reinforcing existing structures provided the necessary

experience and a better understanding of its possibilities.

5.3.1. Structures considered as cast-in-Situ

It was in the framework of structures which may finally be assimilated to cast-in-situ

structures, totally built in one sequence only, that the most efficient PT tendon layout was

developed.

Indeed, concrete deck structures, incrementally built span-by-span or launched, were initially

heavy as PT tendons embedded in the concrete were made continuous by means of expensive

couplers or overlapping. The weight of such deck structures having a major impact on the cost

of the projects, it was undoubtedly attractive to design these bridge decks with a fully external

tendon layout leading to:

-

a reduced cross-section area, as there is no tendon in the concrete anymore;

a better efficiency of the PT tendons, as the area of the cross-section is reduced;

a PT tendon layout basically designed for the completed bridge while adjustable to the

erection method used (Figure 28);

Due to the remarkable fixity of the prestressing line (Figure 29) when the representative

tendon layout of the deck is continuous and globally moved from pier to pier, it can be shown

that the best tendon layout has to be funicular of a uniform distributed load slightly higher

than permanent loads.

It can also be easily demonstrated that trapezoidal tendons, going from pier to pier and simply

deviated at third span points, lead to the suitable tendon layout as soon they are funicular of

concentrated loads representing 75 % of the uniformly distributed loads mentioned above.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 24 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

Permanent deviated tendons (blue & red)

Temporary deviated tendons (green)

(Antagonist tendons)

Permanent straight tendons (yellow)

Figure 28 : Arrangement of external tendons inside the concrete box of an incrementally launched deck

In all of these structures the external prestressing has the remarkable advantage of being

continuous in each span, so there is no discontinuity in the prestressing forces, and the

structural lightness (generally less than 0.50 m mean thickness) is clearly seen to be a

principal characteristic of this type of construction.

2

0

0

-1

-1

-2

-2

-3

-3

-4

Figure 29 : Fixity of the prestressing line

(Any of the representative prestressing line generates the same stresses in the girder)

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 25 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

5.3.2. Segmental bridges built according to the balanced cantilever method

The structures previously mentioned comprise a tendon profile in a certain manner linked to

the construction method and not directly transposable to more traditional means, in particular

balanced cantilever construction.

However, the simplicity and absence of discontinuity of continuous exposed tendons is a

seducing factor for bridge designers and had lead to the development of better tendon profiles

than was usual in these structures.

The tendons comprise three families:

-

The necessary cantilever tendons, inside the top slab gussets and almost entirely

straight

Some continuity tendons, inside the bottom slab gussets and almost entirely straight

also

A maximum of continuous exposed tendons, placed at the end of construction and

anchored at the abutment diaphragms

and these tendon families are found with regularity in the structures built by the balanced

cantilever method.

5.3.3. New structures fully prestressed by external tendons

External prestressing also opened up new horizons for geometry, materials and combination

of materials.

New structures which may be the "structures of the

future" took form thanks to the new degrees of

freedom found in external prestressing and more

especially in the field of composite steel-concrete

structures for which a framework, where the webs are

made of thin corrugated steel panels or steel trusses,

does not drain axial compressive forces and increase

the efficiency of the cross-section in combined

bending and axial load.

Many bridges have already been built in this way and

all of these examples show how developments in

technology and construction methods have been

integrated into the construction of economic

structures.

Figure 30 : Corrugated Web Bridge

5.4.

External prestressing technology

Generally speaking, external or exposed prestressing consists of unbonded tendons located

outside the structural concrete which could also be called "prestressing stays".

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 26 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

The lack of bond does not mean a lack of quality.

On the contrary, this is a technical solution which has advantages as we will see hereafter.

The behaviour of the structures prestressed with external tendons is, if they are properly

designed, as good as the classical ones.

There are two families of external multi-strand tendons:

-

The non-replaceable tendons (as, for example, the multi-strand tendons placed in a

cement-grouted duct)

The replaceable tendons (as, for example, the galvanised multi-strand tendons).

5.4.1. Cement-grouted non replaceable tendons

These tendons are made of several wires or strands grouped in steel pipes or, more frequently,

in straight polyethylene sheaths connected to steel pipes embedded in concrete anchor blocks

or deviation diaphragms. All the characteristics of these tendons (pipe diameter, curvature,

radius, anchorages) are similar to the traditional tendons embedded in the structural concrete.

5.4.2. Cement-grouted replaceable tendons

These tendons are also made of wires or strands placed inside steel or plastic (High Density

Poly Ethylene) ducts able to withstand the grouting pressure.

To be replaceable, therefore dismountable, these tendons must be designed with regard to

their replacement:

-

The anchorages have to be placed in concrete blocks so that it is possible to have easy

access to them

The typical sheath must be placed in other pipes (with a sufficient diameter) so that

the whole cement-grouted tendon can be extracted everywhere it is passing through

the concrete.

In these cases the tendon profile must be either straight or perfectly circular:

-

Grouting of anchorages has to be easily removable

Sufficient space for jacks must be provided for tensioning of new cables if any

replacement is made

It must be pointed out that the replacement of such external tendons can only be done with

destruction of them and it is necessary, prior to cutting external cables injected with cement

grout, to take care with regard to safety requirements.

5.4.3. Replaceable tendons protected by a soft material

These cables are made of wires and more often strands necessarily placed in a steel pipe,

along the circular parts of the tendon profile, in a steel or a polyethylene pipe elsewhere.

They are protected against corrosion by filling the remaining voids between strands and

sheath with grease or wax.

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 27 -

1st International Symposium on Bridges and Large Structures

The technology near the anchorages is then a classical one, sufficient place being provided so

that the tendons can be removed and if necessary, replaced and tensioned.

5.4.4. Galvanised tendons

Although they are not often employed, galvanised tendons can be used and left unprotected,

but then tendon-holding devices must be provided at very short intervals, to prevent damage

in case of a strand or cable breaking.

5.5.

Particular problems related to external prestressing

Problems (or inconveniences) arising from external prestressing are directly related to its

simplicity. First of all, the long straight lengths which appear in the tendon profile between

diaphragms and anchorages can be at the origin of unsuspected vibrations in the exposed

tendons and careful attention must be paid in order to avoid this.

Secondly, the anchorages become increasingly important especially when prestressing is fully

external and replaceable.

In this case, the strength of the structure is determined by the resistance at tendon anchorages,

and although an isolated incident amongst a large number of tendons is not a danger to

structural strength, it is best to try to obtain the highest possible safety factor.

Finally, the abutment diaphragms must be built to resist considerably high and concentrated

forces (several thousand tonnes) posing important stability and diffusion problems.

Voluminous diaphragms are therefore required.

The technology differs according to whether the tendons are designed to be replaceable or not.

Today, several technological solutions allow replacing of external tendons if necessary. The

many advantages which result of such a possibility are at the origin of the development and

success of external prestressing worldwide.

References

[1] Evolution of Bridge Technology Man-Chung Tang 2007 IABSE Symposium in

Weimar Proceedings

[2] Construction Methods Jacques Mathivat & Jacques Combault Ecole Nationale des

Ponts et Chausses

[3] Development and progress in modern bridges with totally external prestressing" (1986

- Southeast Asian Congress on Roads Highways and Bridges - Kuala Lumpur 1986 Conference Proceedings)

[4] The Maupr Viaduct near Charolles, France" (1988 - National Steel Construction

Conference - AISC - Miami 1988 - Proceedings ; 1988 Asia-Pacific Confrence and

September 1988 - Hong Kong)

[5] Competitivity of Concrete Structures (Proceedings of the XIIIth FIP

Congress/Amsterdam/Netherlands Challenges for Concrete in the Next Millesium

May 1998 Key Note Lecture)

J. Combault Conceptual Design of bridges

- 28 -

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- EM 1110-2-2901 Tunnels and Shafts in RockDocument236 paginiEM 1110-2-2901 Tunnels and Shafts in Rockxhifrah100% (3)

- Highway Design Manual: Chapter 19: Reinforced Concrete Box Culverts and Similar StructuresDocument40 paginiHighway Design Manual: Chapter 19: Reinforced Concrete Box Culverts and Similar StructuresKashif Masud100% (2)

- Wireless Sensor and Actuator Networks: Technologies, Analysis and DesignDe la EverandWireless Sensor and Actuator Networks: Technologies, Analysis and DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culvert Design ManualDocument54 paginiCulvert Design ManualMahmoud Al NoussÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guardian Edge Client Administrator GuideDocument49 paginiGuardian Edge Client Administrator Guideaj203355Încă nu există evaluări

- Answer SheetDocument8 paginiAnswer SheetChris McoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.b. COMBRI Design Manual Part II EnglishDocument134 pagini2.b. COMBRI Design Manual Part II EnglishdenbarbosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMBRI Part I ENDocument296 paginiCOMBRI Part I ENAlin SalageanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cable StayedDocument289 paginiCable StayedAnurag KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- UntitledDocument83 paginiUntitledErick WanduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Design GuideDocument44 paginiBridge Design GuideMohanraj Venu100% (3)

- Technical InformationDocument88 paginiTechnical InformationViorica DumitracheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre Stressed Concrete (PSC) Girder Superstructure Bridge-SiDocument316 paginiPre Stressed Concrete (PSC) Girder Superstructure Bridge-SiWilfredo Salgado0% (1)

- European Recommendations For The Design of Simple Joints in Steel Structures - 1st Draft 2003 - JaspartDocument152 paginiEuropean Recommendations For The Design of Simple Joints in Steel Structures - 1st Draft 2003 - JaspartZelzozo Zel Zozo100% (3)

- Country Bridge Solutions Construction GuideDocument45 paginiCountry Bridge Solutions Construction GuideAndrew RaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Time-dependent Behaviour and Design of Composite Steel-concrete StructuresDe la EverandTime-dependent Behaviour and Design of Composite Steel-concrete StructuresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design of Concrete Lined Flood Control ChannelsDocument26 paginiDesign of Concrete Lined Flood Control Channelswikoboy100% (1)

- Unlock 波形钢腹板小箱梁结构设计及顶推施工技术研究117页Document117 paginiUnlock 波形钢腹板小箱梁结构设计及顶推施工技术研究117页Paul LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Report Beyer Et Al 2008Document343 paginiResearch Report Beyer Et Al 2008Gardener AyuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visser WillemDocument67 paginiVisser Willemzarmeen aslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- V 110 KM/H 146 MDocument254 paginiV 110 KM/H 146 MvikasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Notes On RC-I (2023-2024)Document53 paginiLecture Notes On RC-I (2023-2024)tekalignÎncă nu există evaluări

- Continuum-Based Micromechanical Models For AsphaltDocument25 paginiContinuum-Based Micromechanical Models For AsphaltHazratullah PaktinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled Attachment 00050Document109 paginiUntitled Attachment 00050Amr HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis and Design of Concrete StructuresDocument614 paginiAnalysis and Design of Concrete StructuresLinda MadlalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction and Building MaterialsDocument12 paginiConstruction and Building MaterialsKhams TaghaÎncă nu există evaluări

- View PDFDocument163 paginiView PDFDeepakSinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge and Tunnel ConceptDocument76 paginiBridge and Tunnel ConceptDhananjay KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rcs I Lecture Note PDFDocument91 paginiRcs I Lecture Note PDFget100% (2)

- Page 1 of 78Document78 paginiPage 1 of 78Wilfharry billyÎncă nu există evaluări

- RETROFIT of REINFORCED CONCRETE MEMBERS Using Advanced Composite Materials-Wang Thesis-2000Document397 paginiRETROFIT of REINFORCED CONCRETE MEMBERS Using Advanced Composite Materials-Wang Thesis-2000sardarumersialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Design Manual Part 3 - July14Final MASTERDocument50 paginiBridge Design Manual Part 3 - July14Final MASTERTsegawbezto75% (4)

- STL 78569Document476 paginiSTL 78569Keyur PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1997 US Army Corps of Engineers Tunnels and Shafts in Rock 236pDocument236 pagini1997 US Army Corps of Engineers Tunnels and Shafts in Rock 236pLo Shun FatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final 026Document158 paginiFinal 026Pawan BhattaraiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volume 2Document649 paginiVolume 2Denny Azumi ZurinairaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Post-Tensioned Stress Ribbon Systems in Long-Span Roofs: Samih Ahmed Guayente MinchotDocument150 paginiPost-Tensioned Stress Ribbon Systems in Long-Span Roofs: Samih Ahmed Guayente MinchotSonamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original - PCA 84Document50 paginiOriginal - PCA 84Victor HP100% (1)

- Kanakubo Toshiyuki, Petr Kabele, Hiroshi Fukuyama, Yuichi Uchida, Haruhiko Suwada, Volker Slowik (Auth.), Keitetsu Rokugo, Tetsushi Kanda (Eds.) Strain Hardening Cement Composites_ Structural Design and PerformDocument94 paginiKanakubo Toshiyuki, Petr Kabele, Hiroshi Fukuyama, Yuichi Uchida, Haruhiko Suwada, Volker Slowik (Auth.), Keitetsu Rokugo, Tetsushi Kanda (Eds.) Strain Hardening Cement Composites_ Structural Design and PerformJohn GiannakopoulosÎncă nu există evaluări

- AHSS Ver3Document131 paginiAHSS Ver3spocajtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigation of the Chirajara Bridge CollapseDe la EverandInvestigation of the Chirajara Bridge CollapseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karoumi PHD ThesisDocument208 paginiKaroumi PHD ThesisVan Cuong PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Repair Manual: Road Development Authority Japan International Cooperation AgencyDocument140 paginiBridge Repair Manual: Road Development Authority Japan International Cooperation AgencyDilum VRÎncă nu există evaluări

- AnalysisDocument7 paginiAnalysisRazosFyfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mehran Vafaei DissertationDocument60 paginiMehran Vafaei DissertationAmano GhzayelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Health Monitoring and Life-Cycle Costing of Structures. Application To Cable-Stayed BridgesDocument62 paginiStructural Health Monitoring and Life-Cycle Costing of Structures. Application To Cable-Stayed BridgesAsun RajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Constructional Steel Research: Inas Mahmood Ahmed, Konstantinos Daniel TsavdaridisDocument15 paginiJournal of Constructional Steel Research: Inas Mahmood Ahmed, Konstantinos Daniel TsavdaridisPrapa KaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- EM - 1110-2-2901-Tunnel and Shafts in Rock PDFDocument236 paginiEM - 1110-2-2901-Tunnel and Shafts in Rock PDFAsier CastañoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FICEB - Design GuideDocument42 paginiFICEB - Design GuideJaleel ClaasenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design of Concrete Buildings For Disassembly: An Explorative ReviewDocument19 paginiDesign of Concrete Buildings For Disassembly: An Explorative Reviewmonica singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - Schalk Van Der MerweDocument41 pagini1 - Schalk Van Der MerwePieter Vd MerweÎncă nu există evaluări

- RBDG MAN 015 0105 - RailwaySubstructurePart1 EmbankmentsAndEarthworksDocument47 paginiRBDG MAN 015 0105 - RailwaySubstructurePart1 EmbankmentsAndEarthworksjack jackÎncă nu există evaluări

- FEM-10-2-08 2009-10-10 Static Steel Pallet Racks Under Seismic Conditions PDFDocument86 paginiFEM-10-2-08 2009-10-10 Static Steel Pallet Racks Under Seismic Conditions PDFsandiluluÎncă nu există evaluări

- AASHTO LRDF Bridge Construction SpecificationsDocument48 paginiAASHTO LRDF Bridge Construction SpecificationsJithesh.k.sÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Assgmn Final. by MuseDocument50 paginiBridge Assgmn Final. by MuseMister TasewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collapse analysis of externally prestressed structuresDe la EverandCollapse analysis of externally prestressed structuresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Hydraulics: Hydrodynamic and Pollutant Transport Models of Lakes and Coastal WatersDe la EverandEnvironmental Hydraulics: Hydrodynamic and Pollutant Transport Models of Lakes and Coastal WatersEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Passive RF and Microwave Integrated CircuitsDe la EverandPassive RF and Microwave Integrated CircuitsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Nuclear Commerce: Its Control Regime and the Non-Proliferation TreatyDe la EverandNuclear Commerce: Its Control Regime and the Non-Proliferation TreatyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nonlinear Traction Control Design for Parallel Hybrid VehiclesDe la EverandNonlinear Traction Control Design for Parallel Hybrid VehiclesÎncă nu există evaluări

- SDH / SONET Explained in Functional Models: Modeling the Optical Transport NetworkDe la EverandSDH / SONET Explained in Functional Models: Modeling the Optical Transport NetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incompressible Flow Turbomachines: Design, Selection, Applications, and TheoryDe la EverandIncompressible Flow Turbomachines: Design, Selection, Applications, and TheoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steel StructuresDocument56 paginiSteel StructuresAwais Safder Malik0% (1)

- 003 LEER Bim Chapter 4cDocument49 pagini003 LEER Bim Chapter 4cJimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis and Design of Reinforced Concrete Shell ElementsDocument232 paginiAnalysis and Design of Reinforced Concrete Shell ElementsRenish RegiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rev 26Document66 paginiRev 26Mario Alejandro Suarez RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 001 Srs 457Document224 pagini001 Srs 457Jimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- ETABS-Example-RC Building Seismic Load - Time HistoryDocument59 paginiETABS-Example-RC Building Seismic Load - Time HistoryMauricio_Vera_5259100% (15)

- 024 Okk 091008 PDFDocument89 pagini024 Okk 091008 PDFJimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams - Prof. F.KDocument299 paginiReinforced Concrete Deep Beams - Prof. F.Kward_civil036694100% (5)

- CIDECT Design Guide 9Document213 paginiCIDECT Design Guide 9paris06250% (2)

- 05 009 CRDocument194 pagini05 009 CRJimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 002-Basic Civil Engineering BookDocument300 pagini002-Basic Civil Engineering BookJimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Structural EngineeringDocument44 paginiIntroduction To Structural Engineeringadian09Încă nu există evaluări

- Full Scale AnalysisDocument43 paginiFull Scale Analysispaulogud6170Încă nu există evaluări

- AT3 Post Tensioning Miroslav Vejvoda FINALDocument30 paginiAT3 Post Tensioning Miroslav Vejvoda FINALptqc2012Încă nu există evaluări

- Post Tension BIJAN AALAMIDocument14 paginiPost Tension BIJAN AALAMIKhaled Abdelbaki50% (6)

- 705 Carpinteri Mod PDFDocument10 pagini705 Carpinteri Mod PDFJonathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Res2000 2Document130 paginiRes2000 2Subodh ChaturvediÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flat Slab DesignDocument76 paginiFlat Slab Designyunuswsa97% (36)

- 003-RakMek 2 3 1969 1Document7 pagini003-RakMek 2 3 1969 1Jimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deflection of Symmetric Beams: Chapter SevenDocument49 paginiDeflection of Symmetric Beams: Chapter SevenrenebbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seismic Load AnalysisDocument99 paginiSeismic Load AnalysisMANDARAW100% (1)

- Brochure Stay Cables PDFDocument32 paginiBrochure Stay Cables PDFJulio Rafael Terrones VásquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAP2000 - A To Z ProblemsDocument194 paginiSAP2000 - A To Z ProblemsKang'ethe GeoffreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter1 at Basic of RCC PDFDocument44 paginiChapter1 at Basic of RCC PDFTapu mojumderÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 Vol5 581Document8 pagini8 Vol5 581sharvan10Încă nu există evaluări

- Formulas For Columns Witi-1 Side Loads and Eccentricity: November 1950Document24 paginiFormulas For Columns Witi-1 Side Loads and Eccentricity: November 1950Jimmy Villca SainzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Special Moment FramesDocument31 paginiSeismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Special Moment FrameswilfredÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deck SlabDocument12 paginiDeck SlabAhsan SattarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slab Drop PanelDocument4 paginiSlab Drop PanelMahmoud Moustafa ElnegihiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Data WarehousingDocument42 paginiIntroduction To Data WarehousingXavier Martinez Ruiz50% (2)

- BMT-S4-RCC Structures Class - 02june2021Document56 paginiBMT-S4-RCC Structures Class - 02june2021aishÎncă nu există evaluări

- WM3250 Spec SheetDocument2 paginiWM3250 Spec Sheetobiwan2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Wagner Nick - Moving To Oracle 10g How To Eliminate DowntimeDocument28 paginiWagner Nick - Moving To Oracle 10g How To Eliminate DowntimeTamil100% (1)

- Pars of PuneDocument33 paginiPars of PuneAnu Alreja100% (2)

- Aircrete Blocks Technical ManualDocument95 paginiAircrete Blocks Technical Manualpseudosil100% (3)

- Plagiarism ReportDocument27 paginiPlagiarism ReportKuldeep MunjaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Escola Municipal: Data: - / - / - Professor Aplicador: Professor: Nome Do AlunoDocument5 paginiEscola Municipal: Data: - / - / - Professor Aplicador: Professor: Nome Do AlunoJane Kesley BrayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 - Chapter 4 Technical Feasibility StudyDocument24 pagini13 - Chapter 4 Technical Feasibility Studyangelica marasiganÎncă nu există evaluări

- VRRP Cisco DasarDocument32 paginiVRRP Cisco Dasardewi trisnowatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swissotel KolkataDocument2 paginiSwissotel KolkataaddykoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prannoy S Statement of Purpose For MS in Structures in Arizona State UniversityDocument2 paginiPrannoy S Statement of Purpose For MS in Structures in Arizona State UniversityRavi ShankarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Industrial Automation AcronymsDocument3 paginiIndustrial Automation AcronymsPlatin1976Încă nu există evaluări

- Split Air Conditioner: Installation Manual Residential Air ConditionersDocument15 paginiSplit Air Conditioner: Installation Manual Residential Air ConditionersLionelkeneth120% (1)

- Rawlbolt: Shield Anchor Loose BoltDocument6 paginiRawlbolt: Shield Anchor Loose BoltAvish GunnuckÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lect. 8 Sun PathDocument13 paginiLect. 8 Sun PathHitesh KarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity Management Process MapDocument7 paginiActivity Management Process Mapsalesforce.com100% (2)

- Standard Calculation For Outdoor Lighting PDFDocument7 paginiStandard Calculation For Outdoor Lighting PDFankit50% (2)

- Green Expo CenterDocument99 paginiGreen Expo Centerzoey zaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architectural Tropical Design ReviewerDocument10 paginiArchitectural Tropical Design ReviewerFrannie BorrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- RFA - Precast Lifting PDFDocument76 paginiRFA - Precast Lifting PDFLa'Lu O ConnorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geomembranes For Geofoam Applications PDFDocument22 paginiGeomembranes For Geofoam Applications PDFΘανάσης ΓεωργακόπουλοςÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Architecture PDFDocument15 paginiPhilippine Architecture PDFMa Teresita Millano100% (2)

- App12 - ACI Meshed Slab and Wall DesignDocument51 paginiApp12 - ACI Meshed Slab and Wall DesignDario Manrique GamarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- HSDPA Throughput Optimization Case StudyDocument18 paginiHSDPA Throughput Optimization Case StudySandeepÎncă nu există evaluări

- PD I 2000 LecturesDocument624 paginiPD I 2000 LecturesBhaskar ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bee Hotel PlansDocument7 paginiBee Hotel PlansAdam WintersÎncă nu există evaluări

- BS8110 Span-Depth Ratios PDFDocument1 paginăBS8110 Span-Depth Ratios PDFRezart PogaceÎncă nu există evaluări