Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Subacromial Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: The Dilemma of Diagnosis

Încărcat de

TomBrambo0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

82 vizualizări4 paginiPhysical therapy

Titlu original

Lewis_0913

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentPhysical therapy

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

82 vizualizări4 paginiSubacromial Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: The Dilemma of Diagnosis

Încărcat de

TomBramboPhysical therapy

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 4

fag

KRONIKK

Subacromial impingement syndrome

and rotator cuff tendinopathy:

The dilemma of diagnosis

Dr Jeremy S

Lewis, PhD MSc

(Manipulative Physiotherapy) FCSP.

Consultant Physiotherapist, Sonographer. Research

and Innovation Lead,

Health at Stowe,

Central London

Community Healthcare NHS Trust.

Reader in Physiotherapy Research, University of Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire,

UK. Email:

jeremy.lewis@LondonShoulderClinic.com

Web: www.LondonShoulderClinic.com

Denne fagkronikken ble akseptert

06.03.2013. Fagkronikker vurderes av

fagredaktr.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal pathology involving the

shoulder is associated with substantial morbidity and loss of function that increases

with age (1-3). It is generally considered

that effective treatment is dependent upon

understanding the mechanism of onset together with identification of the structure(s)

involved with the symptoms and excluding

those not involved. Mechanisms may involve; trauma, inappropriate ergonomic setup, posture, repetitive and/or unaccustomed

loading, systemic illness, local disease, or be

idiopathic. Following routine clinical procedures that include; observation, assessment

of active and passive movements, palpation,

and resistance tests, a series of orthopaedic

tests are commonly applied to identify the

structure(s) responsible for the pain and

44

Fysioterapeuten 9/13

sub-optimal function (4). Orthopaedic

shoulder tests fall into a number of different categories. Tests have been proposed

to identify instability; such as the load and

shift, sulcus and provocation tests (5).The

Neer impingement sign (6), the Hawkins

test (7) and the internal rotation resistance

strength test (8) have been proposed to assess impingement. Clinicians identify labral

pathology utilising tests such as the; OBrien

active compression test (9) the Crank test

(10) and Kim test (11). Recommendations to identify rotator cuff and biceps

tendon pathology include; Speeds test (4),

Yergasons test (4) and Empty can test (12).

Clinical tests are devised by designing a clinical test to stretch, contract and/or compress a specific shoulder tissue. The diagnostic accuracy of the test is then determined by

comparing the clinical outcome with a gold

standard comparison, such as; radiography,

ultrasound scan, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and direct observation such as during open or arthroscopic surgery. The gold standard tests involve

observation of structural pathology, and it

is this structural pathology which is considered to be the source of symptoms. In

the shoulder, structural pathology such as;

rotator cuff tendinopathy, bursal effusion,

partial and full thickness rotator cuff tears,

labral lesions and degenerative joint changes

are considered to generate symptoms and

the symptoms produced during the clinical

tests are compared against these changes.

For example weakness and pain during the

empty can test becomes diagnostic for supraspinatus pathology (tendinosis through

to full thickness tear) if an US or MRI scan

demonstrates structural failure. A true positive occurs when the gold standard test

is positive (ie observable rotator cuff tear)

and the clinical test is positive (ie pain and

weakness). A true negative is when the clinical test is negative (ie no pain and weakness)

and the gold standard test (ie MRI and US)

does not demonstrate any structural failure.

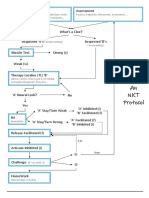

This process allows for the construction of

the classic 2x2 table used to determine diagnostic accuracy (Figure 1).

In this example if a patient presents with

a painful shoulder and a test for a labral tear

is positive and an MRI demonstrates a labral

tear this would be a true positive. If the

clinical test does not produce symptoms and

an MRI demonstrates no labral pathology,

then this is a true negative. Clinical tests that

produce only true positive and true negative

results provide clinicians with considerable

diagnostic confidence to enable clinical

reasoning, treatment planning and patient

education. However, situations occur

Figure 1 2x2 Table used to compare clinical findings and gold standard structural changes.

Reference test

positive +ve

Reference test

negative -ve

Clinical test

positive +ve

(a)

True positive

(b)

False positive

Clinical test

negative -ve

(c)

False negative

(d)

True negative

Some clinicians have recognised that making a

structural diagnosis is challenging and have moved towards a symptoms modification approach.

Mobilization If a single SSMP procedure totally alleviates symptoms, treatment is instigated to

reduce the kyphosis. This may be done by postural awareness exercises, strengthening exercise,

stretching, thoracic mobilizations and taping. Photo: Heidi Johnsen

when the clinical test is negative and the

diagnostic reference test is positive, and the

clinical test is positive and the diagnostic

reference test is negative. These results are

respectively known as false negatives and

false positives. For a clinical assessment

procedure to be of clinical value to identify

symptomatic pathology in only one

structure both the sensitivity of the test (true

positive/true positive and false negative),

and specificity of a test (true negative/true

negative and false positive), both must be

as close to 100% as possible (13). This

can only occur if the clinical test assesses

only one structure and the gold standard

reference tests only demonstrate structural

pathology when symptoms are present.

Reproduction of symptoms

If the sensitivity is high (ie close to 100%),

but the specificity is low, then the clinician

will be able to reproduce symptoms, but in

reality will not know which structure is causing the symptoms. Unfortunately this is the

case for the majority of tests designed to test

for impingement and rotator cuff pathology.

The clinical tests often reproduce the symptoms of pain and weakness, but frequently

the reference tests are negative, and equally

the clinical tests are negative and the reference tests are positive (14-17). Sometimes

the specificity of a test may only be 50% (16,

17) which would not allow the clinician to

develop an informed opinion as to where

the symptoms were coming from. Calis et

al (18) reported a sensitivity of 88.7% and

a specificity of 30.5% for the Neer impingement sign. Litaker et al (19) reported values

of 97.4% and 9.0% for the same test. Calis

et al (18) reported sensitivity and specificity

values of 92.1% and 25% for the Hawkins

test. These figures clearly question the ability

to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Hegedus

et al (20) have recently published a comprehensive review investigating clinical shoulder tests. They concluded that the use of any

single shoulder orthopaedic tests to make a

conclusive diagnosis is questionable.

If diabetes is suspected, it is conceivable

that both clinicians and patients might be

reluctant to commence insulin therapy if a

blood test was only 50% accurate in detecting diabetes as the cause of the presenting

symptoms. However many patients are being referred for surgery (subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair) on the

basis of clinical tests that cannot definitively

confirm a diagnosis and imaging tests that

might demonstrate structural pathology

but the structural changes may be entirely

asymptomatic (15, 21-26).

There are many reasons why the clinical

orthopaedic tests for the shoulder are incapable of isolating individual structures.

These include; (i) rotator cuff tendons that

are not individual units but attach to other

tendons and tissues such as ligaments and

capsules (27, 28), and (ii) the presence of

up to 12 bursae around the shoulder (29)

that are capable of generating pain (30).

These structures may be stretched and/or

compressed in all the shoulder orthopaedic

tests. In addition to this, weakness may not

be true weakness, but be due to pain inhibition (31, 32). It is not known why structural

change may not be symptomatic, but with

studies reporting that up to 50% or more of

people without symptoms may have structural change (21, 22, 24, 25), imaging cannot

inform a clinician conclusively where the

symptoms are emanating from. These issues

have recently been explored in detail (15,

26).

Currently it appears that the process of

making a diagnosis using a combination

of clinical tests supported by imaging findings will not allow a clinician to arrive at a

structural diagnosis with certainty (26). This

has been recognized by clinicians treating

other areas of the body (33, 34).

The Shoulder Symptom Modification

Procedure

With respect to the shoulder, some clinicians have recognized that making a structural diagnosis is challenging and have moved

towards a symptoms modification approach

(26, 35, 36). One such process is known as

the Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure (SSMP) (26). The SSMP involves a sequential process that aims at immediately

Fysioterapeuten 9/13

45

FAG kronikk

identifying postures and techniques that

will reduce symptoms. Initially a number of

postures, movements and activities that reproduce shoulder symptoms are identified,

quantified and qualified. These are patient

determined and are associated with symptoms that if reduced or eliminated would

make a measureable improvement to the

quality of the patients life. Once identified,

the first procedure is to determine the immediate effect of altering the thoracic kyphosis on the symptoms. This is either done

actively or in the case of more challenging

functions, such as; swimming, throwing,

push ups or other complex upper limb function, tape is used to control the kyphosis

(26). If this single procedure totally alleviates

symptoms, treatment is instigated to reduce

the kyphosis. This may be done by postural

awareness exercises, strengthening exercise, stretching, thoracic mobilizations and

taping. The SSMP algorithm requires each

technique to be tested on 2 separate occasions to ensure the effect of any modification

procedure is consistent and mechanical. If

the thoracic procedure reduces symptoms

by 100% on two occasions, treatment is only

directed at treating this. If reducing the kyphosis makes no impact on symptoms then

the next part of the algorithm is assessed.

If reducing the kyphosis results in a partial

reduction in symptoms, the effect of this is

then added to the next part of the algorithm.

The next part of the algorithm involves assessing three planes of scapular position and

combinations of positions on symptoms.

This may be done during weight bearing and

non-weight bearing activities. The changes

to scapular position are minimal and are

not designed to restrict or facilitate scapular

movement. They only serve to alter the starting position of the scapula and the way the

scapular moves on the thorax and articulates

with the humeral head. Again if this procedure alone or in combination with the thoracic procedure results in 100% reduction in

symptoms on two occasions, the assessment

procedure is stopped and treatment commenced. If all symptoms are not resolved,

then the next part of the algorithm is assessed. The next component of the SSMP is to investigate the relationship between the glenoid fossa and humeral head. This component

assesses the glenohumeral relationship by

using up to 13 very quick procedures. Testing stops if one or a combination of techniques results in 100% reduction of symptoms

46

Fysioterapeuten 9/13

(on two occasions). As with the other parts

of the SSMP algorithm, techniques that are

used to assess and reduce symptoms are then

used to inform techniques that are used to

treat. As this is patient lead, it is hoped that

improved compliance results from the fact

it is the patient that has identified what is

helping to reduce their symptoms. The final

component of the Shoulder Symptom Modification procedure is determining the effect

of neuromodulation procedures on shoulder

symptoms. This involves, manual therapy,

taping and soft tissue based techniques. If all

the symptoms are eliminated by one part or

a combination of components of the SSMP,

then no further investigation is required. If

the SSMP fails to reduce any symptoms (as

will happen with frozen shoulder), another

care pathway is instigated. If the SSMP partially reduces symptoms, then a determination

of the reasons for the remaining symptoms is

made and appropriate treatment instigated.

Common reasons for this are a concomitant

rotator cuff and/or biceps tendinopathy. In

addition to using the componenets of the

SSMP that reduced symptoms, alternative

treatment is instigated respecting the stage

of the tendinopathy (37). It is essential that

prior to applying the SSMP other causes of

pain and symptoms such as sinister pathology/red flags are carefully and thoroughly

screened for (38). If the patient fails to respond, then an appropriate onward referral

is mandatory.

Conclusions

The SSMP has been advocated due to the

clinical dilemma of making a definitive

structural diagnosis. The reliability of the

procedure is currently being tested in intra- and inter-tester reliability studies, and

its ability to inform management will also

be subject to future research. In addition to

shoulder management approaches such as

the Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure (26), effort is required to develop ways

to improve methods of making a structural

diagnosis through enhanced clinical and

imaging procedures.

References

1. Brox JI. Regional musculoskeletal conditions: shoulder pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17(1):33-56.

2. van der Heijden GJ. Shoulder disorders: a state-of-the-art

review. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13(2):287-309.

3. Taylor W. Musculoskeletal pain in the adult New

Zealand population: prevalence and impact. N Z Med J.

2005;118(1221):U1629.

4. Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 3rd ed. Philadel-

phia: WB Saunders Co; 1997.

5. Tzannes A, Paxinos A, Callanan M, Murrell GA. An assessment

of the interexaminer reliability of tests for shoulder instability.

Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and

Elbow Surgeons [et al]. 2004;13(1):18-23. Epub 2004/01/22.

6. Neer CS, 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clinical orthopaedics and

related research. 1983(173):70-7.

7. Hawkins RJ, Kennedy JC. Impingement syndrome in athletes.

The American journal of sports medicine. 1980;8(3):151-8.

8. Zaslav KR. Internal rotation resistance strength test: a new

diagnostic test to differentiate intra-articular pathology from

outlet (Neer) impingement syndrome in the shoulder. Journal

of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow

Surgeons [et al]. 2001;10(1):23-7.

9. OBrien SJ, Pagnani MJ, Fealy S, McGlynn SR, Wilson JB. The

active compression test: a new and effective test for diagnosing labral tears and acromioclavicular joint abnormality. The

American journal of sports medicine. 1998;26(5):610-3.

10. Liu SH, Henry MH, Nuccion SL. A prospective evaluation of

a new physical examination in predicting glenoid labral tears.

The American journal of sports medicine. 1996;24(6):721-5.

11. Kim SH, Park JS, Jeong WK, Shin SK. The Kim test: a novel

test for posteroinferior labral lesion of the shoulder--a comparison to the jerk test. The American journal of sports medicine.

2005;33(8):1188-92.

12. Jobe FW, Moynes DR. Delineation of diagnostic criteria and

a rehabilitation program for rotator cuff injuries. The American

journal of sports medicine. 1982;10(6):336-9.

13. Sackett D, Straus S, Richardson W, Rosenberg W, Haynes R.

Evidence-based medicine. How to teach and practice EBM. 2

ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

14. Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy / subacromial impingement syndrome: Is it time for a new method of assessment?

British journal of sports medicine. 2008.

15. Lewis JS. Subacromial impingement syndrome: A musculoskeletal condition or a clinical illusion? Physical Therapy Review.

2011;16(5):388-98.

16. Lewis JS, Tennent TD. How effective are diagnostic tests

for the assessment of rotator cuff disease of the shoulder?

In: MacAuley D, Best TM, editors. Evidenced Based Sports

Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

17. Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, Morin A, Tamaddoni

M, Moorman CT, 3rd, et al. Physical examination tests of the

shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual

tests. British journal of sports medicine. 2008;42(2):80-92;

discussion

18. Calis M, Akgun K, Birtane M, Karacan I, Calis H, Tuzun F.

Diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial

impingement syndrome. Annals of the rheumatic diseases.

2000;59(1):44-7.

19. Litaker D, Pioro M, El Bilbeisi H, Brems J. Returning to the

bedside: using the history and physical examination to identify

rotator cuff tears. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1633-7.

20. Hegedus EJ, Goode AP, Cook CE, Michener L, Myer CA, Myer

DM, et al. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians

with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update

of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests.

British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46(14):964-78. Epub

2012/07/10.

21. Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M. Rotatorcuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand

dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(2):296-8.

22. Frost P, Andersen JH, Lundorf E. Is supraspinatus pathology

as defined by magnetic resonance imaging associated with

clinical sign of shoulder impingement? Journal of shoulder and

elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et

al]. 1999;8(6):565-8.

23. Connor PM, Banks DM, Tyson AB, Coumas JS, DAlessandro

DF. Magnetic resonance imaging of the asymptomatic shoulder

of overhead athletes: a 5-year follow-up study. The American

journal of sports medicine. 2003;31(5):724-7.

24. Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zlatkin MB. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic

shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):10-5.

25. Miniaci A, Mascia AT, Salonen DC, Becker EJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder in asymptomatic professional

Revmatiske leddsykdommer: Effekt av gruppebehandling

i oppvarmet basseng

Sammendrag av Bassengprosjektet.

Skrevet av Anne Christie, fysioterapeut,

Ph.d., Nasjonalt Kompetansesenter for

revmatologisk rehabilitering - NKRR, Diakonhjemmet Sykehus, Oslo.

Bakgrunn: Til tross for at gruppebehandling i oppvarmet basseng er hyt

verdsatt av personer med revmatisk leddsykdom er de helsemessige gevinstene av

slik behandling ikke tilstrekkelig vitenskapelig dokumentert. Hensikten med

prosjektet er underske effekt av gruppebehandling i oppvarmet basseng p

symptomer og fysisk aktivitetsniv hos

denne pasientgruppen.

Personer med inflammatorisk revmatisk leddsykdom kan oppleve store svingninger i symptomer, bde i lpet av en

dag og over tid. P grunn av sykdommens

svingende forlp kan det vre vanskelig

skille behandlingseffekt fra sykdommens

naturlige svingninger. Prosjektet benytter

derfor en metode med mange gjentatte

mlinger fr, under og etter bassengbehandlingen (interrupted time-series design = ITS). Tradisjonelt har pasientrapporterte data blitt samlet inn ved hjelp av

sprreskjema (gullstandard), men denne

metoden er lite egnet ved mange og hyppige mlinger.

Tekstmeldinger over mobiltelefon

baseball pitchers. The American journal of sports medicine.

2002;30(1):66-73.

26. Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy/subacromial impingement syndrome: is it time for a new method of assessment?

British journal of sports medicine. 2009;43(4):259-64.

27. Clark J, Sidles JA, Matsen FA. The relationship of the glenohumeral joint capsule to the rotator cuff. Clinical orthopaedics

and related research. 1990(254):29-34.

28. Clark JM, Harryman DT, 2nd. Tendons, ligaments, and

capsule of the rotator cuff. Gross and microscopic anatomy. J

Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(5):713-25.

29. Codman E. The Shoulder: Rupture of the supraspinatus

tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa.

Boston: Thomas Todd Company; 1934.

30. Gotoh M, Hamada K, Yamakawa H, Inoue A, Fukuda H.

Increased substance P in subacromial bursa and shoulder pain

in rotator cuff diseases. J Orthop Res. 1998;16(5):618-21.

31. Steenbrink F, de Groot JH, Veeger HE, Meskers CG, van de

Sande MA, Rozing PM. Pathological muscle activation patterns

in patients with massive rotator cuff tears, with and without

subacromial anaesthetics. Manual therapy. 2006;11(3):231-7.

32. Wassinger CA, Sole G, Osborne H. The role of experimen-

(SMS) har vist seg egnet for dette designet,

i tillegg til at metoden gir mulighet for registrering av tid og dato for rapportering.

Pilotprosjekt: Metodeutprving: I

pilotprosjektet ble SMS (ny metode) sammenlignet med sprreskjema (gullstandarden). Hensikten med pilotprosjektet

var to-delt: 1)Teste metodens funksjonalitet og 2)Sammenligne tekstmelding (ny

metode) med sprreskjema (gullstandard).

Metode: Tjue-tte deltakere besvarte

daglig 4 sprsml (smerte, tretthet, stivhet

og evne til utfre daglige aktiviteter) p

en gradert numerisk skal (0 - 10, 10 = best)

over en periode p 28 pflgende dager.

Annenhver dag fikk deltakerne tilsendt

flgende SMS:

Fra 0-10, angi grad av smerte, tretthet,

stivhet og evne til utfre daglige aktiviteter n? 0 = ingen, 10 = verst tenkelig. Husk

punktum mellom tallene. TAKK!

Fullstendig tekst var gitt deltakerne p

plastbelagte kort i lommeformat.

Deltakerne skulle svare p SMS ved

taste inn det tallet de syntes passet best for

hvert sprsml og skille tallene med punktum, eks. 6.3.7.5. Annenhver dag skulle

deltakerne besvare de samme sprsmlene

p sprreskjema.

Data fra SMS ble lastet ned via en sikret

server, mens data fra sprreskjema mtte

tally-induced subacromial pain on shoulder strength and

throwing accuracy. Manual therapy. 2012;17(5):411-5. Epub

2012/04/17.

33. OSullivan P. Its time for change with the management of

non-specific chronic low back pain. British journal of sports

medicine. 2012;46(4):224-7. Epub 2011/08/09.

34. Hegedus EJ, Cook C, Hasselblad V, Goode A, McCrory DC.

Physical examination tests for assessing a torn meniscus in

the knee: a systematic review with meta-analysis. The Journal

of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2007;37(9):54150. Epub 2007/10/18.

35. Mulligan BR. Manual Therapy Nags, Snags, MWMs

etc. 4th ed. New Zealand: Plane View Services; 1999.

36. McKenzie R, Watson G, Lindsay R. Treat your own shoulder.

New Zealand: Spinal Publications New Zealand Limited; 2009.

37. Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. British journal of

sports medicine. 2010;44(13):918-23.

38. Greenhalgh S, Self J. Red flags: A guide to identifying

serious pathology of the spine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone

Elsevie; 2006.

plottes manuelt.

Forelpige resultater fra pilotprosjektet viser (ikke publiserte data): Skrer

(gjennomsnitt) og variasjon (SD og range)

var sammenlignbare mellom de to formatene. SMS datasettene var mer komplette

enn datasettene fra sprreskjemaene. Deltakerne foretrakk SMS som metode.

Hovedprosjektet: Multisenterstudie

med deltakelse fra Haugesund Sanitetsforening Revmatismesykehus, Revmatismesykehuset i Lillehammer og Rehabiliteringssenteret Nord-Norges Kurbad i

Troms.

Intervensjon: Poliklinisk gruppebehandling i oppvarmet basseng (> 32 grader) en gang per uke 45 min over en 12

ukers periode. Behandlingen instrueres av

fysioterapeut og vektlegger trening av bevegelighet, styrke, utholdenhet og balanse.

Gruppene flges over fire perioder: To

perioder med bassengbehandling og to perioder uten bassengbehandling.

Metode: Datainnsamling med SMS 2

x per uke.

Status per 1. mars 2013: Annen omgang med intervensjon er i gang p alle

tre steder. Datainnsamlingen avsluttes i

tidsrommet 30. mai - 20. juni (avhengig av

sted).

Studien er enda ikke publisert.

Other relevant resources:

- Download copies of the Shoulder Symptom Modification

Procedure at www.LondonShoulderClinic.com

- Podcast: Prof Jeremy Lewis: Rotator cuff tendinopathies. BMJ

Group Podcasts

http://podcasts.bmj.com/bjsm/

- Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy/subacromial impingement syndrome: is it time for a new method of assessment?

British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43(4):259-64.

http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/43/4/259.long

- Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. British Journal of

Sports Medicine. 2010;44(13):918-23.

http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/44/13/918.full.pdf+html

- Lewis JS. Subacromial impingement syndrome: A musculoskeletal condition or a clinical illusion? Physical Therapy Review.

2011;16(5):388-98.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/1743288X11Y.0000000027.

Fysioterapeuten 9/13

47

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Musculosketal Imaging in Physical TherapyDocument14 paginiMusculosketal Imaging in Physical TherapyWasemBhatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementDe la EverandDisorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Scapular Stabilization Based Exercise Therapy On PDFDocument15 paginiThe Effects of Scapular Stabilization Based Exercise Therapy On PDFElisabete SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balance and Vestibular Rehabilitation KitDocument9 paginiBalance and Vestibular Rehabilitation Kitmsnobody8Încă nu există evaluări

- Plug in GaitDocument70 paginiPlug in GaitJobin VargheseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab: Motor Pattern Assessment Screening & Diagnosis: Albert J Kozar DO, FAOASM, RMSKDocument72 paginiLab: Motor Pattern Assessment Screening & Diagnosis: Albert J Kozar DO, FAOASM, RMSKRukaphuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- PunctumFix Liebenson SundayLectureDocument17 paginiPunctumFix Liebenson SundayLecturepfi_jenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mike ReinoldDocument20 paginiMike ReinoldVikas Kashnia0% (1)

- 6.motor AssessmentDocument32 pagini6.motor AssessmentSalman KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRI Integration For Geriatrics - Complete FileDocument159 paginiPRI Integration For Geriatrics - Complete Filezhang yangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kaltenborn Evjenth Concept of OMTDocument34 paginiKaltenborn Evjenth Concept of OMTJaan100% (1)

- 231a - Reconsidering The Way We Look at Movement-VCUDocument19 pagini231a - Reconsidering The Way We Look at Movement-VCUwolfgate0% (1)

- Module I - Lesson 3 - 4 - Metabolic - PPT NotesDocument14 paginiModule I - Lesson 3 - 4 - Metabolic - PPT NotesRobson ScozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Frozen ShoulderDocument21 paginiJurnal Frozen ShoulderMega Mulya Dwi FitriyaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cervicovestibular Rehabilitation in Sport-Related Concussion - A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument7 paginiCervicovestibular Rehabilitation in Sport-Related Concussion - A Randomised Controlled TrialhilmikamelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Participation Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements As An Assessment of Function - Part 2Document8 paginiPre-Participation Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements As An Assessment of Function - Part 2gogo36Încă nu există evaluări

- Overhead Throwing: Biomechanics and PathologyDocument7 paginiOverhead Throwing: Biomechanics and Pathologyrapannika100% (1)

- A Kinetic Chain Approach For Shoulder RehabDocument9 paginiA Kinetic Chain Approach For Shoulder RehabRicardo QuezadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Evaluation of Scapular DysfunctionDocument6 paginiClinical Evaluation of Scapular DysfunctionRudolfGerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Costa Rica GlucoseDocument91 paginiCosta Rica GlucoseAnthony HarderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinesiology by Carol OatisDocument2 paginiKinesiology by Carol OatisRakesh Kumar50% (2)

- NKT FlowChart - PDF Version 1 PDFDocument2 paginiNKT FlowChart - PDF Version 1 PDFJay SarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinetic Chain Exercises - Open Versus ClosedDocument4 paginiKinetic Chain Exercises - Open Versus Closedamirreza jmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measurement and EvaluationDocument21 paginiMeasurement and EvaluationIndah YulantariÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRI Integ For Pediatrics (Nov 2020) - Complete ManualDocument208 paginiPRI Integ For Pediatrics (Nov 2020) - Complete Manualzhang yangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lumbopelvic Stability PresentationDocument64 paginiLumbopelvic Stability PresentationDeepi Gurung100% (1)

- Cohen 1992Document5 paginiCohen 1992Adriana Turdean VesaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Shoulder: Theory & Practice: Jeremy LewisDocument3 paginiThe Shoulder: Theory & Practice: Jeremy Lewisparakram0% (1)

- How Could Periodization Help Enhance MuscleDocument9 paginiHow Could Periodization Help Enhance Musclemehrdad_44Încă nu există evaluări

- What Role Does Ethics Play in Sports - Resources - More - Focus Areas - Markkula Center For Applied Ethics - Santa Clara UniversityDocument4 paginiWhat Role Does Ethics Play in Sports - Resources - More - Focus Areas - Markkula Center For Applied Ethics - Santa Clara UniversityManish PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Medical Terms, Abbreviations, and Acronyms Approved For Arizona WIC UseDocument7 paginiCommon Medical Terms, Abbreviations, and Acronyms Approved For Arizona WIC UseAsif Raza SoomroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The IFAST Assessment: Anterior Pelvic TiltDocument6 paginiThe IFAST Assessment: Anterior Pelvic Tiltjole000Încă nu există evaluări

- Phasic Activity of Intrinsic Muscles of The FootDocument14 paginiPhasic Activity of Intrinsic Muscles of The FootpetcudanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Stance On Muscle Activation in The SquatDocument5 paginiThe Effect of Stance On Muscle Activation in The Squatapi-320703111100% (1)

- 1 Reviews Evidences HandoutDocument25 pagini1 Reviews Evidences Handoutsefhilla putriÎncă nu există evaluări

- FUNHAB®: A Science-Based, Multimodal Approach For Musculoskeletal ConditionsDocument9 paginiFUNHAB®: A Science-Based, Multimodal Approach For Musculoskeletal ConditionsVizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Proposed Evidence-Based Shoulder Special Testing Examination Algorithm - Clinical Utility Based On A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument14 paginiA Proposed Evidence-Based Shoulder Special Testing Examination Algorithm - Clinical Utility Based On A Systematic Review of The LiteratureAfonso MacedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1: Basic Principles of Resistance Training andDocument12 paginiChapter 1: Basic Principles of Resistance Training andLuis Eduardo Barbosa Ortega100% (1)

- Access NPTE Review Lecture OutlineDocument12 paginiAccess NPTE Review Lecture OutlinecutlaborcostÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chondromalacia Patella RehabDocument1 paginăChondromalacia Patella Rehabjntownsend3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Ballistic StretchingDocument14 paginiBallistic Stretchingapi-351172625Încă nu există evaluări

- Transverse Rotation of The Segments of The Lower Extremity in LocomotionDocument15 paginiTransverse Rotation of The Segments of The Lower Extremity in Locomotionpetcudaniel100% (1)

- Motor Control The Heart of KinesiologyDocument13 paginiMotor Control The Heart of Kinesiologyferdinal dsakdskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reinold - Glenohumeral and Scapulothoracic RehabDocument45 paginiReinold - Glenohumeral and Scapulothoracic Rehabshivnair100% (2)

- Principles of Test SelectionDocument3 paginiPrinciples of Test SelectionALEX SNEHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Whitley (2022) Periodisation of Eccentrically-Integrated Resistance Training During A National Rugby League Pre-SeasonDocument20 paginiWhitley (2022) Periodisation of Eccentrically-Integrated Resistance Training During A National Rugby League Pre-SeasonMiguel Lampre EzquerraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Exercise Training Intensity On Abdominal Visceral Fat andDocument19 paginiEffect of Exercise Training Intensity On Abdominal Visceral Fat andPepe EN LA LunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rehabilitation of Hamstring Strains: Phase I: Acute PhaseDocument3 paginiRehabilitation of Hamstring Strains: Phase I: Acute PhaseariyatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Body PlanesDocument32 paginiBody PlanesStefanny Paramita EupenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 52 Page PDF PF PPT Neurophysiological Effects of Spinal Manual Therapy in The Upper Extremity - ChuDocument52 pagini52 Page PDF PF PPT Neurophysiological Effects of Spinal Manual Therapy in The Upper Extremity - ChuDenise MathreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kozar ScienceOfMotorControlLectureDocument114 paginiKozar ScienceOfMotorControlLectureMari PaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Framework For Exercise Prescription: DOI: 10.1097/TGR.0000000000000011Document23 paginiA Framework For Exercise Prescription: DOI: 10.1097/TGR.0000000000000011Lft Ediel PiñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kaltenborn 1993Document5 paginiKaltenborn 1993hari vijayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pedia1 NewbornDocument300 paginiPedia1 NewbornNacel CelesteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turocy StainCounterstrain LabPATS06ADocument53 paginiTurocy StainCounterstrain LabPATS06Awillone08Încă nu există evaluări

- PNFpresentationDocument32 paginiPNFpresentationNarkeesh ArumugamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Staged Approach For Rehabilitation ClassificationDocument10 paginiStaged Approach For Rehabilitation ClassificationCambriaChicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Girls and Sport: Female Athlete Triad SimplifiedDe la EverandGirls and Sport: Female Athlete Triad SimplifiedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original Article: Correspondence ToDocument9 paginiOriginal Article: Correspondence ToTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of Blueberry Diseases: Dept. Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences Michigan State UniversityDocument51 paginiOverview of Blueberry Diseases: Dept. Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences Michigan State UniversityTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chronic Pain ManagementDocument44 paginiChronic Pain ManagementTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running and Osteoarthritis Does Recreational or Competitive Runn 2017Document1 paginăRunning and Osteoarthritis Does Recreational or Competitive Runn 2017TomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rotator Cuff Shoulder Pain DiagnosticDocument14 paginiRotator Cuff Shoulder Pain DiagnosticTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Posterior Shoulder Tightness: To Treat or Not To Treat?: ViewpointDocument4 paginiPosterior Shoulder Tightness: To Treat or Not To Treat?: ViewpointTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Routine InfographicDocument1 paginăBasic Routine Infographicariraphiel100% (2)

- Growing Blueberries PDFDocument8 paginiGrowing Blueberries PDFOlivera PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blueberry Varieties For MichiganDocument6 paginiBlueberry Varieties For MichiganTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dominion Temne CasyDocument5 paginiDominion Temne CasyTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Specific Exercise Program and Modification of Postural Alignment For Treating of CHDocument13 paginiA Specific Exercise Program and Modification of Postural Alignment For Treating of CHTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Scapular Position On Cervical ROMDocument6 paginiInfluence of Scapular Position On Cervical ROMTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yellow Flags-Psychological IndicatorsDocument1 paginăYellow Flags-Psychological IndicatorsTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Manual Therapy and Neurodynamic Techniques VsDocument10 paginiEffect of Manual Therapy and Neurodynamic Techniques VsTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment Manual and Therapy Map Greg Lehman Feb 2015Document26 paginiTreatment Manual and Therapy Map Greg Lehman Feb 2015TomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Modern Pain Neuroscience in Clinical - 2014Document12 paginiApplying Modern Pain Neuroscience in Clinical - 2014Juci FreitasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Isometric, Eccentric, or Heavy Slow Resistance Exercises On Pain and Function With PTDocument15 paginiEffects of Isometric, Eccentric, or Heavy Slow Resistance Exercises On Pain and Function With PTTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Specific Exercise Program For Impingement RMDocument2 paginiSpecific Exercise Program For Impingement RMTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment Manual and Therapy Map Greg Lehman Feb 2015Document26 paginiTreatment Manual and Therapy Map Greg Lehman Feb 2015TomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Scapular Position On Cervical ROMDocument6 paginiInfluence of Scapular Position On Cervical ROMTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoulder Derangement With An Underlying DysfunctionDocument28 paginiShoulder Derangement With An Underlying DysfunctionTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation The Patient Using MDTDocument34 paginiEvaluation The Patient Using MDTTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postural Exercises On The Foam RollDocument3 paginiPostural Exercises On The Foam RollTomBrambo100% (1)

- Peripheral Mobilisation S With MovementDocument9 paginiPeripheral Mobilisation S With MovementTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Core Engaged Leg RaiseDocument1 paginăCore Engaged Leg RaiseTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theoaknee MDTDocument67 paginiTheoaknee MDTTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toe Touch ProgressionDocument1 paginăToe Touch ProgressionTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Straight Leg TDocument1 paginăStraight Leg TTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toe Touch ProgressionDocument1 paginăToe Touch ProgressionTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wall SitDocument1 paginăWall SitTomBramboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 4Document79 paginiLecture 4alaa emadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cholera Outbreaks in Sub Saharan AfricaDocument7 paginiCholera Outbreaks in Sub Saharan AfricaMamadou CoulibalyÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Doi 10.1043 - 0003-3219 (2006) 076 (0388 - VOPRFM) 2.0.CO 2)Document6 pagini(Doi 10.1043 - 0003-3219 (2006) 076 (0388 - VOPRFM) 2.0.CO 2)Bulfendri DoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical AppraisalDocument47 paginiCritical AppraisalNaman KhalidÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1b Static & Dynamic Characteristics&Loading Effect PDFDocument45 pagini1b Static & Dynamic Characteristics&Loading Effect PDFvishnuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnostic Value of Gastric Shake Test For Hyaline Membrane Disease in Preterm InfantDocument6 paginiDiagnostic Value of Gastric Shake Test For Hyaline Membrane Disease in Preterm InfantNovia KurniantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSA Level and Gleason Score in Predicting The Stage of Newly Diagnosed Prostat CancerDocument6 paginiPSA Level and Gleason Score in Predicting The Stage of Newly Diagnosed Prostat CancergumÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Model and Empirical Research of Application Scoring Based On Data Mining MethodsDocument8 paginiThe Model and Empirical Research of Application Scoring Based On Data Mining MethodsGuilherme Miguel TavaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sensitivity and SpecificityDocument3 paginiSensitivity and SpecificityPrisia AnantamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap 012Document84 paginiChap 012Noushin Khan0% (2)

- Salmo 6579Document7 paginiSalmo 6579DiegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saple Sze CCDocument14 paginiSaple Sze CCPeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Geochemistry: Mouigni Baraka Nafouanti, Junxia Li, Nasiru Abba Mustapha, Placide Uwamungu, Dalal AL-AlimiDocument8 paginiApplied Geochemistry: Mouigni Baraka Nafouanti, Junxia Li, Nasiru Abba Mustapha, Placide Uwamungu, Dalal AL-Alimik.ayushearth28Încă nu există evaluări

- Bio-Stats Step 3Document9 paginiBio-Stats Step 3S100% (4)

- Prosper 444 PDFDocument27 paginiProsper 444 PDFaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1368837518304299 MainDocument8 pagini1 s2.0 S1368837518304299 MainIgor VainerÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Scoring System APACHE HF For PredictDocument9 paginiNew Scoring System APACHE HF For PredictAdi PriyatnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHN QuestionsDocument13 paginiCHN QuestionsKristine CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- All Common ChecklistDocument66 paginiAll Common Checklistyousrazeidan1979Încă nu există evaluări

- Hemix: Technical SpecificationsDocument3 paginiHemix: Technical SpecificationsNia AmbarwatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010 Article 1133Document15 pagini2010 Article 1133Asmaa ElarabyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Plagiarism Report (Before Removing)Document21 paginiProject Plagiarism Report (Before Removing)Shyam Raj SivakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Scientific and Statistical Computing (IJSSC) Volume (1) IssueDocument18 paginiInternational Journal of Scientific and Statistical Computing (IJSSC) Volume (1) IssueAI Coordinator - CSC JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- (TNHS) : Summary and ExplanationDocument12 pagini(TNHS) : Summary and Explanationcass100% (2)

- Webster BioinstrumentationDocument394 paginiWebster BioinstrumentationMaria Jose GardeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Notes - Logistic RegressionDocument11 paginiLecture Notes - Logistic RegressionPrathap BalachandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic and Clinical Biostatistics, 5th EditionDocument368 paginiBasic and Clinical Biostatistics, 5th Editionmp4Încă nu există evaluări

- A Clinical Scoring System For Pediatric Hand - Foot-Mouth DiseaseDocument8 paginiA Clinical Scoring System For Pediatric Hand - Foot-Mouth DiseaseclaudyÎncă nu există evaluări

- TDX Oli DMR PS 4105Document3 paginiTDX Oli DMR PS 4105Ethan LynnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seratec Hemdirect Hemoglobin Assay: Intended Use Description of The TestDocument2 paginiSeratec Hemdirect Hemoglobin Assay: Intended Use Description of The Testfabiola_magdalenoÎncă nu există evaluări