Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Christian Moral Principles

Încărcat de

JR Deviente0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

43 vizualizări2 paginiThis document discusses St. Thomas Aquinas' view of natural law as presented in Catholic teaching. It outlines that natural law refers to basic practical principles that people naturally understand, such as that good should be done and pursued while evil avoided. These principles of natural law correspond to fundamental human goods and inclinations. The document also examines formulations for the first principle of morality, which guides choices toward integral human fulfillment through compatible willing of human goods. It notes a need for intermediate moral principles between the first principle and specific norms.

Descriere originală:

Christian Moral Principles

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis document discusses St. Thomas Aquinas' view of natural law as presented in Catholic teaching. It outlines that natural law refers to basic practical principles that people naturally understand, such as that good should be done and pursued while evil avoided. These principles of natural law correspond to fundamental human goods and inclinations. The document also examines formulations for the first principle of morality, which guides choices toward integral human fulfillment through compatible willing of human goods. It notes a need for intermediate moral principles between the first principle and specific norms.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

43 vizualizări2 paginiChristian Moral Principles

Încărcat de

JR DevienteThis document discusses St. Thomas Aquinas' view of natural law as presented in Catholic teaching. It outlines that natural law refers to basic practical principles that people naturally understand, such as that good should be done and pursued while evil avoided. These principles of natural law correspond to fundamental human goods and inclinations. The document also examines formulations for the first principle of morality, which guides choices toward integral human fulfillment through compatible willing of human goods. It notes a need for intermediate moral principles between the first principle and specific norms.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 2

CHRISTIAN MORAL PRINCIPLES

Chapter 7:Natural Law and the Fundamental Principles of Morality

Summary

Much Catholic teaching on natural law refers to the work of St. Thomas

Aquinas, and Vatican II commends him as a guide. We can therefore examine

his treatment of natural law to see how the Church views the subject.

Law for St. Thomas primarily means a reasonable plan of action. He begins

from what he calls the eternal lawGods plan in creating and redeeming.

Any other reasonable plan of action must somehow derive from it. People

can plan their lives reasonably only because, in one way or another, they

share in the universal plan present in Gods law; to the extent they try to

follow some other plan, their lives are unrealistic.

Human beings, according to St. Thomas, are naturally disposed to

understand some basic practical principles. These are the primary principles

of natural lawwhat St. Paul calls the law written in ones heart (see Rom

3.1416). However, truths of natural law, including specific norms, are also

part of revelation. As Vatican I says, this is in part so that even in the

present condition of the human race, those religious truths which are by their

nature accessible to human reason can readily be known by all men with

solid certitude and with no trace of error (DS 3005/1786; translation

supplied). Thus natural law and divine law can be distinguished, but not

separated and opposed.

Practical thinking is reasoning and judging about what might and ought to

be. According to St. Thomas, its first principle is: The good is to be done and

pursued; the bad is to be avoided. Scholastic natural-law theory formulated

this as a moral imperative: Do good and avoid evil. But, as Thomas

formulation shows, the first principle is not a moral norm. It expresses the

intrinsic, necessary connection between human goods and actions which

bear upon them; in thinking about what one might do, it is impossible to

disregard entirely the goods and bads involved.

People grasp as goods all the fulfillments to which they are naturally inclined.

Corresponding to each natural inclination, therefore, is a basic precept of

natural law: Such and such a basic human good is to be done and/or

pursued, protected, and promoted. These are general determinations of the

first principle. In their light we can see why human nature and natural law

morality are both stable and changing: stable because they are based on

fundamental, unalterable natural inclinations; changing because these

potentialities are open to continuing, expanding fulfillment.

But such principles of practical reasoning do not tell us what is morally good.

Moral norms are needed to guide choices toward the fulfillment of persons in

relation to human goods.

The first principle of morality might best be formulated as follows: In

voluntarily acting for human goods and avoiding what is opposed to them,

one ought to choose and otherwise will those and only those possibilities

whose willing is compatible with a will toward integral human fulfillment.

Note that this conceives human goods not simply as diverse fields for

possible action, but as together comprising the totality of integral human

fulfillment. This avoids subordinating moral reflection to specific objectives;

instead, the upright person is to remain open to goods which go beyond his

or her present capacity for realizing them in action.

There is also need for intermediate principles of morality, midway between

the first principle and the completely specific norms which direct particular

choices. These are the modes of responsibility. An example is the principle of

fairness or impartiality expressed by the Golden Rule. These modes exclude

choices involving various unreasonable (immoral) relationships of willing to

the human goods. People who are thinking in a morally sound way commonly

take them for granted. But for the most part they have not been

systematically discussed up to now, though at one time or another almost

every one of them has been mistaken for the first principle of morality.

Scripture and Christian moral teaching do not speak of modes of

responsibility but of virtues. However, the virtues do not constitute moral

norms distinct from the modes; rather, virtues embody modes. For virtues

are aspects of a personality integrated around good commitments, and the

latter are choices in accord with the first principle of morality and the modes

of responsibility.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Natural Law and Moral NormsDocument30 paginiNatural Law and Moral NormsAudrey C. JunsayÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 6 The Norms of MoralityDocument8 paginiCHAPTER 6 The Norms of MoralityGabbi RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Word of Love Gives Inspiration To Life, A Word of Care Gives Happiness To The Heart, A Word of God Gives Direction To Our Life.-Airene TDocument4 paginiA Word of Love Gives Inspiration To Life, A Word of Care Gives Happiness To The Heart, A Word of God Gives Direction To Our Life.-Airene TRubz Jean100% (1)

- The Norms of MoralityDocument31 paginiThe Norms of Moralityroseangellequin08Încă nu există evaluări

- (Ignou) EthicsDocument178 pagini(Ignou) EthicsKshitij Ramesh Deshpande100% (2)

- Ethics Moral Philosophy IGNOU Reference MaterialDocument58 paginiEthics Moral Philosophy IGNOU Reference MaterialAshish GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHL 5 Morality of Human ActionDocument7 paginiPHL 5 Morality of Human ActionMich TolentinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Basic Moral PrinciplesDocument2 pagini4 Basic Moral Principlesapi-3528789700% (1)

- Natural Law, The Understanding of Principles, and Universal GoodDocument36 paginiNatural Law, The Understanding of Principles, and Universal GoodEziel Rosales AballeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duty EthicsDocument6 paginiDuty EthicsJamaica DUMADAGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of Law ReportDocument5 paginiPhilosophy of Law ReportalshaniabathaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FINALS Module 4lesson 1 6 Module 5 Lesson 1 3Document7 paginiFINALS Module 4lesson 1 6 Module 5 Lesson 1 3Princess FloraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Additional SourcesDocument22 paginiAdditional SourcesBelle Pattinson LautnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature and Scope of EthicsDocument10 paginiNature and Scope of EthicsSreekanth ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kantian Duty Based Theories of EthicsDocument8 paginiKantian Duty Based Theories of EthicsNithya NambiarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law and MoralsDocument11 paginiLaw and MoralsRyrey Abraham PacamanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics Modules 5 and 6Document13 paginiEthics Modules 5 and 6Shean BucayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kantian Duty Based (Essay)Document7 paginiKantian Duty Based (Essay)Chelliah SelvavishnuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHL 5 Morality of Human ActionDocument7 paginiPHL 5 Morality of Human ActionMich TolentinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements of Morals: With Special Application of the Moral Law to the Duties of the Individual and of Society and the StateDe la EverandElements of Morals: With Special Application of the Moral Law to the Duties of the Individual and of Society and the StateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module IiDocument16 paginiModule IiDickson Tk Chuma Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 5Document12 paginiUnit 5Ayushi sahuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sources of Ethical StandardsDocument9 paginiSources of Ethical StandardsMooka SitaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kantian Duty BasedDocument7 paginiKantian Duty BasedJOMARI DL. GAVINOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 2.3 The PHILOSOPHY of INTERSUBJECTIVITYsubthemepromoting The Human WelfareDocument6 paginiLesson 2.3 The PHILOSOPHY of INTERSUBJECTIVITYsubthemepromoting The Human WelfareJayvie AljasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 1-2 Ethics Vs MoralDocument5 paginiWeek 1-2 Ethics Vs MoralMaria Teresa FaminianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deontological EthicsDocument4 paginiDeontological EthicsNEET ncert readingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acting on Principles: A Thomistic Perspective in Making Moral DecisionsDe la EverandActing on Principles: A Thomistic Perspective in Making Moral DecisionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gula, Chap 15-16 On Natural LawDocument31 paginiGula, Chap 15-16 On Natural LawÔng TiênÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural Vs Positive LawDocument14 paginiNatural Vs Positive Lawfreedriver_13Încă nu există evaluări

- Moral Theology at The Intersection of Rational Dimension, Sacred Dimention and Conscience DimensionDocument10 paginiMoral Theology at The Intersection of Rational Dimension, Sacred Dimention and Conscience DimensionJayanth FranklyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Norms of MoralityDocument22 paginiNorms of MoralityNorielyn Espejo100% (2)

- On The Metaphysics of Morals and Ethics: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals; Introduction to the Metaphysic of Morals; The Metaphysical Elements of EthicsDe la EverandOn The Metaphysics of Morals and Ethics: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals; Introduction to the Metaphysic of Morals; The Metaphysical Elements of EthicsEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, Memoirs…De la EverandThe Collected Works of John Stuart Mill: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, Memoirs…Încă nu există evaluări

- Aquinas LawsDocument7 paginiAquinas LawsAviral MauryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics Utilitarianism and Kantian EthicsDocument5 paginiEthics Utilitarianism and Kantian Ethicsapi-3729409100% (4)

- ERIC JOHN R NEMI-PA214 (Deontology)Document5 paginiERIC JOHN R NEMI-PA214 (Deontology)Nemz KiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morality and PropertiesDocument16 paginiMorality and Propertieslyssa janinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The John Stuart Mill Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays)De la EverandThe John Stuart Mill Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays)Încă nu există evaluări

- John Stuart Mill: Collected Works: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy…De la EverandJohn Stuart Mill: Collected Works: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy…Încă nu există evaluări

- What Are My Guideposts To Know Where I Am Going?Document31 paginiWhat Are My Guideposts To Know Where I Am Going?AJ Grean EscobidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DMK - Module8 GE8 ETHDocument10 paginiDMK - Module8 GE8 ETHJINKY TOLENTINOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macintyre Privatization of The GoodDocument18 paginiMacintyre Privatization of The GoodBruno ReinhardtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural Law: Thomas AquinasDocument5 paginiNatural Law: Thomas AquinasShem Aldrich R. BalladaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abortion and Virtue Ethics-1Document35 paginiAbortion and Virtue Ethics-1Jemma Rose SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deontological Ethics 1Document7 paginiDeontological Ethics 1Samy BoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judaism and Natural Law Jonathan JacobsDocument18 paginiJudaism and Natural Law Jonathan JacobspruzhanerÎncă nu există evaluări

- JOHN STUART MILL - Ultimate Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays): Autobiography, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive and MoreDe la EverandJOHN STUART MILL - Ultimate Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays): Autobiography, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive and MoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Camag, Angelica, GEN SCI BDocument3 paginiCamag, Angelica, GEN SCI BAntonio VallejosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Division of EthicsDocument8 paginiDivision of EthicsJeremy Marinay100% (1)

- Normative EthicsDocument9 paginiNormative EthicskrunalpshahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handout 8 - Kant S EthicsDocument3 paginiHandout 8 - Kant S EthicsZia CaldozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural Law EssayDocument13 paginiNatural Law EssayConrad EspinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics ReviewerDocument4 paginiEthics ReviewerPAOLO MIGUEL MUNASÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Immorality of Contraception According To Love and Responsibility of Karol WojtylaDocument9 paginiThe Immorality of Contraception According To Love and Responsibility of Karol WojtylaJayson Resol ResurreccionÎncă nu există evaluări

- FMT7 - Natural Law and MoralityDocument41 paginiFMT7 - Natural Law and Moralitymark loganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Made byDocument18 paginiMade byJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

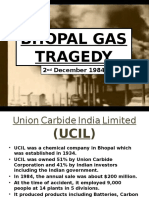

- Bhopal LeeDocument24 paginiBhopal LeeJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhopal Gas Tragedy: 2 December 1984Document10 paginiBhopal Gas Tragedy: 2 December 1984JR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Credit Procedures and ControlsDocument5 paginiCredit Procedures and ControlsJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Entity Relationship Diagram: A Complete Guide To Design ER DiagramsDocument25 paginiEntity Relationship Diagram: A Complete Guide To Design ER DiagramsJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For Writing A Literature ReviewDocument6 paginiGuidelines For Writing A Literature ReviewJR Deviente50% (2)

- Diskpart Format Fs Ntfs QuickDocument1 paginăDiskpart Format Fs Ntfs QuickJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pro LifeDocument8 paginiPro LifeJR DevienteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Messiah in The SiddurDocument28 paginiMessiah in The SiddurAlastair Simpson100% (2)

- Devi SuktamDocument3 paginiDevi SuktamSathis KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 SummerDocument12 pagini2016 SummergeorgioskchasiotisÎncă nu există evaluări

- C S Lewis Deliberately Promoted A Paganised Form of ChristianityDocument23 paginiC S Lewis Deliberately Promoted A Paganised Form of ChristianityJeremy James69% (16)

- Galatians and RomansDocument345 paginiGalatians and RomansemmanueloduorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1: Servant Leadership Overview of TheDocument3 paginiModule 1: Servant Leadership Overview of TheCalvin Dante Barrientos100% (1)

- Spiritual Gift Assessment - by Pastor Christian EkotoDocument5 paginiSpiritual Gift Assessment - by Pastor Christian EkotoSaPPMinistryÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Was A Time Where Prophet Was Meditating in The Hira CaveDocument3 paginiThere Was A Time Where Prophet Was Meditating in The Hira CaveFitri YusofÎncă nu există evaluări

- Star of BethlehemDocument8 paginiStar of BethlehemIgor19OgÎncă nu există evaluări

- GC Kuntaraf Spiritual Gift Assesment PDFDocument36 paginiGC Kuntaraf Spiritual Gift Assesment PDFDarenFerreiroTheneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who Is The Real Enemy?Document5 paginiWho Is The Real Enemy?Youthly Scribe100% (3)

- The Value of Self-1Document6 paginiThe Value of Self-1Amy Winkfield OliverÎncă nu există evaluări

- You Are My All in All Canon in D PDFDocument11 paginiYou Are My All in All Canon in D PDFLeyte GerodiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soul Ties-Spiritual StrongholdsDocument24 paginiSoul Ties-Spiritual StrongholdsFERNS100% (5)

- Aelfricslivesof 01 AelfDocument570 paginiAelfricslivesof 01 AelfPeter PicardalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ars Est Celare ArtemDocument34 paginiArs Est Celare ArtemMichael BolerjackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outline of End Time EventsDocument7 paginiOutline of End Time EventsAdrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Johannes Tauler - The Inner Way (1900) MysticismDocument376 paginiJohannes Tauler - The Inner Way (1900) MysticismWaterwind100% (2)

- Sermon On The Mount - Part 4Document5 paginiSermon On The Mount - Part 4BUMC documentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Our FaithDocument74 paginiThe Importance of Our FaithGiah VillahermosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Every Season of Life Has A PurposeDocument2 paginiEvery Season of Life Has A Purpose3k hotelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wiersbe Bible Commentary OTDocument1.535 paginiThe Wiersbe Bible Commentary OTAngel Senarpida100% (10)

- What A Friend We HaveDocument4 paginiWhat A Friend We HavesrcofcÎncă nu există evaluări

- TD Jakes Whores, Pimps and Gays in Satan's KingdomDocument10 paginiTD Jakes Whores, Pimps and Gays in Satan's KingdomPat Ruth Holliday0% (1)

- CS191 Assignment 2Document3 paginiCS191 Assignment 2Chairul Dian NugrahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SWRB Puritan Hard Drive TitlesDocument545 paginiSWRB Puritan Hard Drive TitleswdeliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 33 - Micah PDFDocument53 pagini33 - Micah PDFGuZsolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donaldson Papers PDFDocument16 paginiDonaldson Papers PDFSammy BlntÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coppieters - Gabriel's MessageDocument3 paginiCoppieters - Gabriel's MessageJade CoppietersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Love vs. LustDocument30 paginiLove vs. LustPringle ZionÎncă nu există evaluări