Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety A Study On

Încărcat de

Maria MirandaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety A Study On

Încărcat de

Maria MirandaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on

Food Safety Regulations

Elzbieta Trybus Gordon Johnson

California State University, Northridge, CA

Recent broadly publicized outbreaks of food-borne illnesses caused by E-coli and Salmonella have

increased public concerns on safety food and food suppliers. Assuring quality and food safety is,

however, critical to the entire supply chain. This paper has two objectives: to get a deeper

understanding of food safety issues in food supply chain management (SCM) and to discuss the role

of federal, state and local agencies in issuing regulations to prevent future outbreaks. As a result,

taxonomy of regulations for product safety is developed.

I. INTRODUCTION

During the last five years thousands of

products and processed food products have been

recalled due to contamination (and potential

contamination) of ingredients. Examples of these

recalls include ground beef, ground beef patties,

contaminated cookie dough, peanuts and peanut

derived products, pistachios, spinach, lettuce, dry

milk, contaminated toys and drywalls. Recalls of

contaminated food and food products have

reduced consumers confidence in the food

systems ability to deliver safe and high quality

products. The Center for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) estimated that food-borne

diseases cause about 76 million illnesses, more

than 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths in

the United States every year (www.cdc.gov).

Food suppliers and food producers are

blamed for these diseases outbreaks. There are

many causes of food-borne disease outbreaks.

Some are related to an improper food

preparation, processing, products transportation

conditions, others to global outsourcing. The

United States imports food from more than 150

different countries through more than 300 ports

of entry.

Contamination of ground beef with E coli

0157:H7 has led to recalls involving millions of

pounds of ground beef: 21.7 million pounds of

beef patties in 2007 and more than 800,000

pounds of ground beef in 2009. Experts think that

more than 70,000 infections per year in the

United States are caused by E. coli 0157:H7

bacteria. A batch of Nestle Toll House

Refrigerated cookie dough contained bacterium

E. coli 0157:H7, causing 34 people to be

hospitalized after eating raw dough (Shepherd,

2009). Contamination of ground beef with E.

coli 0157:H7 resulted about hospitalization of 40

people and two deaths. Salmonella was detected

in products from Peanut Corporation of America

(PCA)s Georgia plant. Up to 9 deaths have been

linked to the peanut case (Schmit, 2009).

Tanimura and Antle Whole Head Romaine

Lettuce were recalled after salmonella was found

in a routine check (Donor, 2009).

Toys manufactured in China by Mattel

contained too much lead and were dangerous for

babies and little kids health (DeNoon, 2007).

Drywalls imported from China in 2002 caused

problematic health symptoms among many

homeowners and their families.

Costs of recalls are in millions of dollars

for the food industry; not including costs of lost

lives and patients hospitalizations. What need to

be done to reduce these risks? Regulators,

producers and retailers are mandated to improve

the quality of food products by redesigning

legislation and quality assurance programs. The

Volume 8, Number 1, pp 93-99

California Journal of Operations Management 2010 CSU-POM

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

US government and regulating agencies conduct

meetings and hearings to improve food safety

and quality in order to prevent and reduce the

number of food-borne disease cases.

The House approved the first major

changes to food-safety laws in 70 years, giving

new authority to the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) to regulate the way food is

grown, harvested and processed. This Food

Safety Bill as reported by The Washington Post

(July 31, 2009) requires food manufacturers to

identify the particular risks they face, create

controls to prevent contamination, monitor those

controls to make sure they are working and

update these measures regularly. Such controls

have been mandatory for the seafood and juice

industries since the 1990s.

Since causes of contamination may occur

at any stage of the supply chain (SC) very often

the authorities, including, federal and state

agencies are unable to identify the origin of a

tainted food product. In such cases, food recalls

or warnings are applied to all suppliers, including

those who did not contribute to the

contamination.

The main purpose of this paper is to get a

deeper understanding of the causes of product

contamination, in particular food products and

discuss the role of federal and state agencies in

food safety regulations.

crisis management and restoration of consumer

evidence, and in Canada and Australia the policy

focus was on risk management and the

prevention of trade-threatening food safety

issues. Since the UK food industry is driven

primarily by domestic market, there were

practically no issues with food safety caused by

global SC. But Mad Cow Disease (the Bovine

Spongiform Encephalopathy, BSE) brought the

public attention to importance of food safety and

quality assurance. The 1990 Food Safety Act

requires buyers to take all reasonable steps to

ensure that food they receive from upstream

suppliers is safe. Also, upstream firms must

demonstrate to their downstream customers that

they are handling food correctly.

In Canada food safety is shared between

the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA)

and Health Canada (HC). In some cases food

safety and inspection standards are under

provincial jurisdiction. In Australia, state

governments were responsible for the

enforcement of food law. But to avoid different

standards across the country the Agriculture and

Resource Management Council of Australia and

New

Zealand

(ARMCANZ)

developed

Australian

Standards

for

processing

establishments servicing the domestic markets

(e.g. meats). In addition, national standards were

developed by the Australia-New Zealand Food

Authority (ANZFA).

Another study on food safety (Buelens et

al. 2003) emphasized the role of partnership in

SCM when improving food safety. The authors

found an impact of building trust in SC network,

improving technology for product traceability

and providing information required by

stakeholders in- and outside of the SC network

very crucial in improving safety of food

products.

Manning et al. (2004) analyzed quality

assurance (QA) model that drives both legislative

and customer compliance. This model requires

two elements: good manufacturing practice/good

agricultural practice (GMP/GAP), and a

benchmarking

protocol

that

measures

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

Food safety is everyones concern and

everyone has a role to play. Consumers, in

particular, are concerned with food safety, and

properties of food they buy and eat. Tools to

assure food safety and quality are important in

the entire SCM, when moving product from farm

to the table.

Introducing incentive structures for

changes in food safety legislation and in private

sector business strategies was discussed by

Hobbs et al. (2002) using three countries as

benchmarks: the UK, Canada and Australia. In

the UK the incentives were primarily related to

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

94

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

performance in a quantitative way. Again, this

model refers to the European standards.

The food safety topics dont have full

recognition in SCM literature. In addition,

textbooks in SCM, like Simchi-Levi et al. (2008)

do not introduce quality issues in the SCM at all.

Other textbooks in SCM, including Burt et al.

(2003), Benton (2007), Jacobs and Chase

(2008), Webster (2008), Wisner (2008), and

Boyer and Verma (2010) expose readers to only

one chapter on quality tools without integrating it

into the SCM. In none of these textbooks food

chains are presented and their importance

discussed.

Controlling complex processes and also

regulations in food chain requires an integrated

approach and a responsible authority to oversee it

in order to protect and promote food safety

(Elmi, M. 2004).

The FDA has an Office of Criminal

Investigation as well. The FDA published the

Food Code to assist state and local governments

to regulate food safety. Usually, the FDA

inspects plants every 5 to 10 years. But in fact

FDA does only about half of all inspections

enforcing state agencies to perform them. This

may create some problems we will discuss later

using Peanut Corporation of America (PCA) in

Georgia as an example.

3.2. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

USDA inspects meat, poultry, and eggs.

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is

the public health agency in the USDA

(www.fsis.usda.gov). The USDA budget includes

inspection for wholesomeness of food, while

meat and poultry producers pay USDAs

Agricultural Marketing Service for quality

inspection (ex USDA Choice).

The legislation for these programs started with

the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Poultry

Products Inspection Act, which affect interstate

and foreign commerce. Food sold only within the

state in which it is produced is regulated by the

state, but the FDA monitors state inspection

programs. In 1967 the Wholesome Meat Act

required state inspection to be at least equal to

the Federal inspection program. FDA and FSIS

collaborate to improve tracing of unsafe food

products.

III. THE ROLE OF FEDERAL, STATE AND

LOCAL HEALTH AGENCIES IN

IMPROVING FOOD SAFETY

This section will summarize the roles of

the different agencies in the United States in the

monitoring, reporting and enforcing food safety

standards.

3.1. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

For more than 100 years, the FDA has

regulated the safety of components of the food

supply. The FDA is currently part of the

Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS) and consists of seven centers and offices

including Center for Food Safety and Applied

Nutrition Organization and Office of Regulatory

Affairs Organization (www.fda.gov). There are 3

elements of the Food Protection Plan:

A. Prevention, including risk assessment of

imported food

B. Intervention, including inspection and

surveillance. Sampling techniques are used to

screen imports

C. Response, including containment of illnesses

and communication to the media.

3.3. Center for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC)

Center for Disease Control (CDC), an

agency within the U. S. Department of Health

and Human Services (HHS), is not a food and

safety regulatory agency but works closely with

the food safety regulatory agencies, in particular

with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) and the Food Safety and Inspection

Service (www.cdc.gov).

Food illnesses which affect many states at

the same time require CDC assistance to

the

states. Examples are widespread outbreaks

affecting a large number of people. CDC can lead

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

95

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

investigations of the cause of a food borne

illness. Included in the CDC is the National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health,

which investigates illnesses from pesticides and

other chemicals. This agency also studies why

farmers have higher incidences of skin diseases

and brain cancer.

chemical, or mechanical hazard. Applications

include toys, cribs, power tools, cigarette

lighters, and household chemicals.

After recalls of lead contaminated toys in

2007 President George W. Bush signed the

Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of

2008 on August 2008. This Act regulates

childrens product safety and provides changes in

the Product Safety Commission. It sets regulation

standards for new levels of acceptable lead

content and mandates a documentation of testing.

It imposes new and more severe penalties and

fines onto companies that break newly regulated

standards. It also mandates a reduction in the

total lead content that can be used in childrens

products. CPSC mandates that childrens toys are

tested by a third party testing facility

(www.cpsc.gov).

3.4. Import Safety

Multiple government agencies are

involved in import safety. For example, the US

Customs and Border Protection agency inspects

food imports.

The National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), within the

Department of Commerce, operates the fee-based

Seafood Inspection Program. At the request of

the US seafood importer of the foreign seafood

facility, NOAA audits the facility to ensure that it

complies with the hazard Analysis Critical

Control Point (HACCP) Quality Management

Program. Also the Department of Agriculture

(USDA) works with foreign exporters to ensure

that fruits and vegetables are free from

agricultural pests and diseases prior to export to

the U.S.A. Coordination between agencies has

been a difficult issue. In 2006 the Security and

Accountability For Every Port Act required an

electronic interface among agencies to address

the issue of different computer systems. In 2007

the Secretary of Health and Human Services

chaired a committee to improve import safety

(www.importsafety.gov).

IV. EXAMPLES OF SYSTEM FAILURES

AND INEFFICIENCIES

The USA system of multiple agencies and

organizations responsible for food safety was

criticized as being inefficient. Dr. Samuel Earl

Fox from the School of Public Health at Johns

Hopkins University (BMJ 2003, report) raised an

issue that food safety regulations are out of date,

inflexible and erratically enforced. The Peanut

Corporation of America (PCA) case in Georgia

and Nestle Cookie Dough case are good

examples of this critique.

3.5

Consumer Product Safety Commission

(CPSC)

The US Consumer Product Safety

Commission created in 1972 is charged with

protecting the public from unreasonable risks of

injuries caused by consumer products. The

Consumer Product Safety Act of 1972 gave the

CPSC control over 15,000 products for which the

commission has the power to create safety

standards and push for recalls if there is a risk of

harm or death to consumers. Under extremes

circumstances the commission can even issue a

ban on a product. Risks include fire, electrical,

4.1. Peanut Butter Case

In 2008 CDC identified first multistate

cluster of Salmonella infection. Through

epidemiologic investigation the outbreak was

traced to peanut butter and peanut butter paste

manufactured in the Peanut Corporation of

America (PCA) located in Blakely, Georgia. In

2001 FDA investigated the production process

and the use of duct tape. The FDA paid the State

of Georgia to send their inspectors to visit PCA

in 2006 and 2008. PCA passed the state

inspections. After the recall, the FDA visited

PCA with strong criticism of the cleanliness of

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

96

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

the plant. The FDA also criticized the PCA

policy of retesting so that the second test might

come back negative. FDA advocated that product

be destroyed after one positive result.

King Nut peanut butter produced by PCA

was not sold directly to consumers but was

distributed to institutions, food service providers,

food manufacturers and distributors in many

states and countries. Kellogg bought PCA

Peanut Paste for its sandwich crackers. Kellogg

sent its employees to visit the PCA plant but did

not do an audit. Both King Nut and Kellogg

hired an auditor, AIB International, who rated

PCAs plant as Superior. However, AIB gives

98% of companies a Superior or Excellent

rating (Schmit, 2009). PCA paid AIB for the

audit and was given one month notice before the

next audit. Critics of the status quo use this as an

argument for a new FDA policy.

Nestle sent its employees to PCAs plant

and rejected PCA as a supplier due to inadequate

cleaning and cross contamination. Nestle did not

send report to the FDA as it is not mandated by

government agencies to report inadequacies in

supplier procedures. Deibel Labs told PCA that

6% of its samples tested positive for salmonella,

but this also was not reported to FDA. Another

issue was cross contamination, when salmonella

from raw nuts is next to roasted nuts. Raw and

roasted nuts must be separated to avoid this

problem. Problems at the PCA plant in Georgia

included duct tape, which can harbor insects and

a leaky roof, which implies salmonella from bird

droppings could get into the plant. Inadequate

cleaning was a pervasive problem for PCA. More

than 2833 peanut containing products produced

by a variety of companies were recalled by PCA.

Some members of Congress advocate that

positive test results of food contamination should

be reported to FDA. William Hubbard, former

FDA Associate Commissioner, said third party

auditors have a conflict of interest or are not well

trained.

4.2. Nestle Cookie Dough Case

In 2009 health officials identified Nestle

Toll House cookie dough as a potential source of

E. coli outbreak. Initially investigators from the

US Government were not able to find

contamination inside the factory or on the

equipment at the Nestle plant in Virginia. David

Acheson, Assistant Commissioner for Food

Safety in the FDA, said this raises the likelihood

that it was an ingredient (Layton 2009). Cookie

dough is made from eggs, milk, butter/margarine,

flour, and chocolate. Nestle restarted cookie

dough production July 7, 2009 with new supplies

of eggs, margarine, and flour, along with a

different label containing a warning not to eat

raw cookie dough.

Recalls issued by a manufacturer or

mandated by a government agency damage

firms reputation, cost lives and lead to

bankruptcy, as it happened to the PAC.

In September 2009 the FDA launched

http:/www.foodsafety.gov with recall bulletins.

The United States Senate will vote this year on

the Food Safety Act, already passed by the

House of Representatives. This bill would give

the FDA the power to issue recalls (Huget, 2009)

since the current law (passed in 1938) only

allows the FDA to request voluntary recalls. The

new bill also requires FDA inspections yearly

(Klein, 2009).

V. ANALYSIS OF TYPICAL CAUSES IN

SELECTED PRODUCTS

CONTAMINATION CASES

As pointed in the previous section there

are situations where finding causes of

contamination is not easy and is taking more time

and resources than expected. Contamination of

lettuce could be caused by human error at the

farm, transportation and handling, or storage.

As an illustration of non-biological causes,

lettuce grown in southeast California contained

perchlorate, a rocket fuel additive (Danelski,

2003).

A Nevada facility contaminated the

Colorado River, whose water irrigated fields of

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

97

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

lettuce in Imperial, Riverside, and San

Bernardino Counties.

Contamination of toys manufactured in

China was caused by using inappropriate paint

provided by a supplier who did not comply with

the quality standards. Investigations revealed that

the cause of this contamination was lead in paint.

Millions of toys were recalled in 2007 when it

was discovered that kids and babies were sick

because of playing with these toys.

Another example is drywalls from China used in

increased amounts after Hurricane Katrina, have

been discovered to be toxic. Sulfuric compounds

within the drywall have had a corrosive effect,

leading to a damage of copper plumbing pipes,

electrical outlets, air-conditioning coils, and other

metallic utilities and furnishings. The sulfur in

these walls emits a rotten-egg smell, allegedly

resulting in nausea, headaches and respiratory

problems. Hundreds of residents in Florida,

Louisiana, and Virginia have been complaining

of noxious gases emitted by Chinese drywalls.

We will summarize typical causes of

contamination by using a 5Ms method also called

cause-and-effect diagram or fish-bone diagram

developed by Ishikawa in Japan. This quality

management tool classifies possible causes into

materials, methods, manpower, machines, and

Mother Nature causes. Below a list of possible

causes is presented.

1. Materials: types of fertilizer, water used for

irrigation and later for cleaning, pesticides,

ingredients, containers and packaging

materials.

2. Methods: documentation and employee

training,

procedures

for

harvesting,

procedures for food processing, cleaning and

sanitation, and transportation.

3. Machines: machines used in harvesting, food

processing, air conditioning, and equipment

for transportation.

4. Manpower: farmers, workers trained in using

methods and machines, workers empowered

to stop the process if there is a problem,

consumers who may need special warnings

and instructions how to use the product.

5. Environment (or Mother Nature): weather

conditions, unexpected disasters including

hurricanes, fires, flood, and earthquakes but

also buildings and storages.

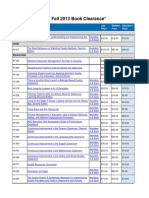

In table 1 we summarize root causes in cases

discussed in this paper.

Thus, the main causes of contaminated

product were materials used in the processes,

machines processing food products, methods and

environment. All these causes and errors should

be removed from the system before product goes

to the consumer. Managers need to provide better

supervision and working structures in the

existing SCM. SCMs.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Our paper indicates that regulations on food

safety do not work in the way they were

originally designed. It takes time for designated

agency to detect the cause of product

contamination. The responsibility of educating

managers, producers, and consumers about the

transmission of food-borne diseases is the

important task for food safety experts. Managers

in food industry should use all available tools to

prevent food contamination and work toward

TABLE 1: IDENTIFICATION OF ROOT CAUSES OF PRODUCT CONTAMINATION

CASE NAME

Nestle Cookie Dough

Peanut butter

Lettuce

Toys (supplied to Mattel)

Toxic Walls

ROOT CAUSE(S)

Materials (raw eggs), policies

Methods, machines, environment

Material (water used in irrigation)

Materials, methods, testing

Materials (toxic ingredients)

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

98

Trybus and Johnson

The Role of Supply Chain Product Safety: A Study on Food Safety Regulations

achieving full compliance with existing and

future food standards and regulations.

Also, quality must be incorporated into the

SCM courses. Cost-benefit analysis of preventing

contamination and implementing necessary

techniques, including better product traceability

should be performed. The main problem, in this

case, is data availability and dissemination of

reports by CDC. The last CDC surveillance

report was published in November of 2006 and

summarizes years 1998 to 2002.

Elmi, M., Food Safety: Current Situation,

Unaddressed Issues and the Emerging

Priorities. Journal of East Mediterranean

Health, 2004, 10(6).

Foster, S.T. Managing Quality: Integrating the

Supply Chain, Prentice Hall, 2010.

Huget, J., Food Borne Illnesses, Washington

Post, September 29, 2009.

Jacobs, F.R. and Chase, R.B., Operations and

Supply Management: The Core, McGrawHill, 2008.

Klein, E., When Good Foods Goes Bad,

Washington Post, September 30, 2009.

Layton, L., E Coli Confirmed in Nestle

Samples, Washington Post, June 30, 2009.

Manning, L. Baines, R.N., and S.A. Chadd,

Quality Assurance Models in the Food

Supply Chain, British Food Journal, 108(2),

2006.

Simchi-Levi, D., Kaminsky, H., and E. SimchiLevi, Designing and Managing the Supply

Chain, McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Schmit, J., Broken System Hid Peanut Plants

Risks, USA Today, April 27, 2009.

Vollmann, T.E., Berry, W.L., Whybark, D.C.,

and F. R. Jacobs, Manufacturing Planning

and Control for Supply Chain Management,

McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Webster, S., Principles and Tools for Supply

Chain Management, McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Wisner, J. D., Tan, K. C., Leong, G. K.,

Principles of Supply Chain: A Balanced

Approach, South Western Cengage Learning,

2008.

VII. REFERENCES

Benton, W.C., Purchasing and Supply Chain

Management, McGraw-Hill/Irvin, 2007.

Beulenes, A. J. M., Broens, D., Folstar, P., and

G. J. Hofstede, Food Safety and

Transparency in Food Chains and Networks:

Relationships and Challenges, Food Control,

16(6), 2005.

Boyer, K.K., and R. Verma, Operations and

Supply Chain Management for the 21

Century, South Western, 2010.

Burt, D.N., Dobler, D.W., and S.L. Starling,

World Class Supply Management: The Key

to Supply Chain Management, McGraw-Hill,

2003.

Danelski, D., Growing Concerns, Riverside

Press Enterprise, April 27, 2003.

DeNoon, D.J., Fischer-Price Toy Recall: What

to Do, WebMD Health News, 2007,

http://www.webmed.com/parenting/news/200

70802/toy-recall-what-parents-should-know.

Deprez., E.E., Chinas Latest Tainted Export:

Toxic Drywall, Business Week, July 13,

2009.

California Journal of Operations Management, Volume 8, Number 1, February 2010

99

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Operational Risk Management - (Chapter 3 Tools and Techniques) PDFDocument38 paginiOperational Risk Management - (Chapter 3 Tools and Techniques) PDFMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Maximizing Asset Health Using Cognitive Fingerprinting™: in The Near Future Sensors Will Be EverywhereDocument2 paginiMaximizing Asset Health Using Cognitive Fingerprinting™: in The Near Future Sensors Will Be EverywhereMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Difference - PageDocument5 paginiDifference - PageMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Automation and Employment in The 21st Century: Texto CompletoDocument4 paginiAutomation and Employment in The 21st Century: Texto CompletoMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Six Sigma Mystery Shopping Nigerian BankingDocument4 paginiSix Sigma Mystery Shopping Nigerian BankingMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Scor P Sample QuestionsDocument6 paginiScor P Sample QuestionsMaria Miranda100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Scor P BulletinDocument10 paginiScor P BulletinMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating ISO 21500 Guidance On Project Management, Lean Construction and PMBOKDocument6 paginiIntegrating ISO 21500 Guidance On Project Management, Lean Construction and PMBOKMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Yard Management Getting Beyond ROI White Paper2Document8 paginiYard Management Getting Beyond ROI White Paper2Maria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- LBC BlueprintDocument9 paginiLBC BlueprintMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Articulo PFDocument5 paginiArticulo PFMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Ultimate Guide To Business Transformation Failure and How To Avoid ItDocument12 paginiThe Ultimate Guide To Business Transformation Failure and How To Avoid ItMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- 10-Basics of Best-in-Class-Lean Manufacturing Best Practice No. 04: Value Stream Mapping by Bill GawDocument1 pagină10-Basics of Best-in-Class-Lean Manufacturing Best Practice No. 04: Value Stream Mapping by Bill GawMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Docslide - Us Asq Clearance BookspdfDocument4 paginiDocslide - Us Asq Clearance BookspdfMaria MirandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Garcia. Act 1 and 2 NUR103Document4 paginiGarcia. Act 1 and 2 NUR103Frances Katherine GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Chapter 12 Glencoe Biology Study GuideDocument11 paginiChapter 12 Glencoe Biology Study GuideabdulazizalobaidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Growth and DevelopmentDocument64 paginiGrowth and DevelopmentRahul Dhaker100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- MTL CHAPTER 9 2020 ClickUpDocument11 paginiMTL CHAPTER 9 2020 ClickUpcharlieÎncă nu există evaluări

- OME Video DurationsDocument7 paginiOME Video DurationsLucas RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hallie Berger Resume 11-2Document2 paginiHallie Berger Resume 11-2api-281008760Încă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Accupressure EyeDocument7 paginiAccupressure Eyemayxanh1234100% (3)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Theory ApplicationDocument38 paginiTheory ApplicationAnusha VergheseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Presentation-Mindy Duran-FinalDocument30 paginiCase Study Presentation-Mindy Duran-Finalapi-278622211Încă nu există evaluări

- Carvalho-2016-About AssesmentDocument19 paginiCarvalho-2016-About AssesmentChiriac Andrei TudorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endodontic Topics Volume 18 Issue 1 2008 (Doi 10.1111/j.1601-1546.2011.00260.x) YUAN-LING NG KISHOR GULABIVALA - Outcome of Non-Surgical Re-TreatmentDocument28 paginiEndodontic Topics Volume 18 Issue 1 2008 (Doi 10.1111/j.1601-1546.2011.00260.x) YUAN-LING NG KISHOR GULABIVALA - Outcome of Non-Surgical Re-TreatmentardeleanoanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contact Lens Complications and ManagementDocument10 paginiContact Lens Complications and Managementstrawberry8832850% (2)

- Cipriani Et Al-2013-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument52 paginiCipriani Et Al-2013-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsfiskaderishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CystsDocument5 paginiCystsranindita maulyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Kuliah PF Jantung Prof IIDocument32 paginiKuliah PF Jantung Prof IIannis100% (1)

- IMNCIDocument13 paginiIMNCIJayalakshmiullasÎncă nu există evaluări

- VBAC MCQsDocument3 paginiVBAC MCQsHanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dorothea Orem: Self-Care TheoryDocument16 paginiDorothea Orem: Self-Care TheoryHazel LezahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ozone Unsung Hero by Navy Captain - Ajit VadakayilDocument153 paginiOzone Unsung Hero by Navy Captain - Ajit Vadakayilsudhir shahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes Mellitus ResearchDocument6 paginiDiabetes Mellitus ResearchJohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Chemistry QuestionsDocument5 paginiClinical Chemistry QuestionsEric C. CentenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature and Characteristics of Services in HospitalsDocument7 paginiNature and Characteristics of Services in HospitalsOun MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To Volunteering at Camphill DevonDocument3 paginiAn Introduction To Volunteering at Camphill DevonjohnyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hipertensi Portal Donny SandraDocument67 paginiHipertensi Portal Donny SandrabobyÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHN RLE Module 1M 3M With Self Assessment 1.2.3 of Rle Module 1mDocument62 paginiCHN RLE Module 1M 3M With Self Assessment 1.2.3 of Rle Module 1mPhilip Anthony Fernandez100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 7 Chapter 7 T-Cell Maturation, Activation, and DifferentiationDocument34 pagini7 Chapter 7 T-Cell Maturation, Activation, and DifferentiationMekuriya BeregaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Class NotesDocument3 paginiMental Health Class Notessuz100% (4)

- Pros and Cons EuthanasiaDocument3 paginiPros and Cons EuthanasiaMirantika Audina100% (1)

- Mediclaim Policy - Buy Group Health Insurance Online - Future GeneraliDocument39 paginiMediclaim Policy - Buy Group Health Insurance Online - Future GeneraliRizwan KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Manual On Surveillance of AEFIDocument128 paginiGlobal Manual On Surveillance of AEFIHarold JeffersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe la EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (6)