Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Political Effects On The Allocation of Public Expenditures

Încărcat de

Giannis BetsasTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Political Effects On The Allocation of Public Expenditures

Încărcat de

Giannis BetsasDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

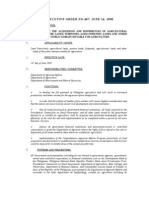

Political effects on the allocation of public expenditures:

Empirical evidence from OECD countries

Niklas Potrafke1

Humboldt University Berlin

This Version: April 20, 2008

Abstract

This paper examines the effects of political determinants on the allocation of public expenditures.

We analyse two data sets of different expenditure categories (COFOG) covering a broad time

period: An OECD panel from 1970 to 1989 as well as from 1990 to 2005. We find that national

policy had stronger impacts till the beginning of the nineties. Leftist governments set other

priorities than rightwing governments, but this required that they had a majority in parliament.

Electoral effects are detected as endogenous and the size of coalition emerges as unimportant.

Keywords: public expenditures, budget composition, partisan politics, political budget cycle,

panel data

JEL Classification: D72, H50, H61, C23

Acknowledgements: We thank Roland Vaubel, Ulrich Oberndorfer, Charles B. Blankart,

Georgios Chortareas, Frank Somogyi, Gunther Markwardt and the participants of the WPCS

2007, of the CESifo Workshop Macroeconomics 2007 and of the DIW Workshop

Macroeconometrics 2007 for helpful comments, hints and suggestions. All errors are our own.

Humboldt University Berlin, Department of Economics and Management Science, Institute of Public Finance,

Competition Policy and Institutions, Spandauer Strasse 1, D-10178 Berlin, Germany, Phone: + 49 30 2093 5788,

Fax: + 49 30 2093 5697. Email: niklas.potrafke@gmx.de

Niklas Potrafke

1. Introduction

This paper examines the political determinants of the budget composition in OECD countries.

The essence is that the allocation of expenditures is an interesting object of investigation in

national fiscal policy because it covers the politicians real room of manoeuvre. Irrespective of the

amount of revenues and expenditures and the need to take care of given allegiances, each

government has to choose the purposes for which it will spend the revenues. It will prioritise.

However, a respective empirical analysis requires data that mirror different policy fields by single

expenditure categories. The more comprehensive the classifications of government expenditure,

the higher the probability that single policy effects are undetected. They might simply

compensate each other. Therefore this paper refers to the classification of functions of

government (COFOG). We analyse the data set by Sanz and Velzquez (2007) and Gemmell et

al. (2007) covering the period from 1970 to 1989 as well as the recent data set from the OECD

for the period from 1990 to 2005 and thereby start examining the budget composition of general

governments more comprehensively than previous literature does.

Analyzing the budget composition enjoys a remarkable popularity in the very recent empirical

literature. Sanz and Velzquez (2007) investigate the role of aging on the allocation process and

detect that aging is the main driving force of the growth of government spending in OECD

countries. Shelton (2007) provides an extensive analysis of different impact factors like

population, country size, fragmentation, income, income inequality, political rights and

institutions. He distinguishes between different levels of government (central, and local) and

considers more than 100 countries. Dreher et al. (2007) analyze whether globalization has

affected the composition of public expenditures also using the KOF index of globalization

(Dreher (2006a) and Dreher et al. (2008)) and do not find any influence. Gemmell et al. (2007)

detect that foreign direct investment significantly shifted the expenditure composition towards

social spending, whereas trade did not. Hence it is still not clear whether budgets are influenced

by international factors. But they may be driven by national policy and political determinants like

the different attitudes and number of parties in the government, the timing of elections etc.

There are a few further studies testing for political effects on the allocation of public

expenditures, but first, they do not examine the detailed budget composition (COFOG) as the

studies listed above. Bruninger (2005) develops a partisan model of government expenditure and

also provides empirical tests in an OECD framework in the period from 1971 to 1999. He finds

that the actual spending preferences of parties matter whereas they do not indicate that parties of

the left consistently differ from parties of the right in their spending behaviour. Tsebelis and

2

Niklas Potrafke

Chang (2004) analyse the impact of veto players on the budget composition. Their results show

that it changes at a slower pace by multiparty governments. However, they choose a different

model set up taking the change in the structure of budgets as dependent variable (budget

distance). Furthermore, there are some single country studies examining the budget composition

in Germany in more detail: Bawn (1999), Galli and Rossi (2002), Knig and Trger (2005) and

Potrafke (2006). In sum, they find that the budget composition is driven by political

determinants. Regarding the political variables the current paper extends the previous research by

first examining the interaction of government ideology and the fact if the respective governments

have a majority in parliament. We expect somewhat mitigated ideology effects under minority

governments. Second we apply an extended variable set of predetermined and endogenous

elections years following Shi and Svensson (2006).

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 provides the institutional

background originating from the theory of political economics. Section 3 presents the data and

discusses their time series properties. In section 4 the empirical model is set up and the political

variables are described. Section 5 discusses the estimation results and section 6 concludes the

analysis.

2. Institutional background

2.1 Political business cycles, partisan approach and government types

The issue of the paper is to test for the effects of election years, the ideological party composition

as well as the type of government on the allocation of public expenditures. The impacts of these

variables on economic activity stem from a huge and model based literature of political

economics. In this paper, our emphasis is not to find evidence for a single theoretical model.

Instead we will very briefly repeat the main ideas of respective (well known) theoretical work

establishing a basis for the following empirical analysis.

First, the political business cycle approaches and the partisan theory clarify how politicians try to

influence economic outcome. One implication of the theories by Nordhaus (1975) and Rogoff

and Sibert (1988) among others is that all politicians will implement the same policy. Ideology

does not matter. Policies will converge. In addition, they imply a particular pattern between

elections on the one hand and the impacts of economic policy on the other hand. Nordhaus

(1975) opportunistic school asserts that politicians fool the public just to win elections. They will

boost economic activity right before elections. The rational political business cycle theory by

Rogoff and Sibert (1988) among others criticizes this modelling for using adaptive expectations

3

Niklas Potrafke

and introduces rational expectations instead. In this approach, information asymmetries play a

role as a source of the electoral cycles. The incumbent tries to exploit his information advantage

by signalling his economic competence before elections. This scientific debate is still alive.

Recently, Shi and Svensson (2006) show that politicians may behave opportunistically even if the

voters know all the government programs, but some individuals are uninformed. Alt and Lassen

(2006) point out that the higher the transparency of the political process, the lower the

probability to behave opportunistically. Finally, we conclude from these approaches that election

years will affect the budget composition so that the preferences of the median voter are fulfilled.

In contrast, the partisan approach focuses on the strong impact of party ideology. As a result,

platforms and policies do not converge. Instead, leftwing and rightwing politicians will provide

different policies by concentrating on the preferences of their partisans. The leftist party appeals

more to the labour base and promotes expansionary policies, whereas the rightwing party appeals

more to capital owners, and is therefore more concerned with reducing inflation. This holds for

both sub-approaches of the partisan theory - for the classical approach of Hibbs (1977), and for

the rational approach of Alesina (1987). The literature on the partisan theory has become more

abundant during the last decades (e.g. Alesina et al. 1997). In fact, Belke made several important

contributions to this literature and introduced the hysteris-augmented rational partisan approach

(Belke 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 1997c and 2000). Overall, our hypothesis is that party constellation

and respective ideologies of the governments affect the budget composition.2 3

Another political determinant stems from the literature on fiscal policy. It arises from the

common pool problem discussed, e.g., by Weingast et al. (1981) and implies that decision costs

increase with the number of decision makers. This also refers to the logic of logrolling. For

example, the collective action literature implies that the more dispersed the decision-making

authority, the higher the budget deficit. Also the amount of government expenditures is expected

to be higher the more parties form a government. Tsebelis (1995) is associated with this so called

early veto player theory. He claims that the potential of a policy change decreases with the

number of veto players, the lack of congruence (dissimilarity of policy positions among veto

players) and the internal cohesion (similarity of policy positions among the constituent units of

This implies that there is divergence of policies and platforms. Theoretically, in a simple two party model, ideology

must over compensate the vote maximizing effect in this case. In a multi party model, manifoldness and traditions of

the parties are assumed to avert policy convergence. See, e.g., Mueller (2003): Chapters 11-13 and Persson and

Tabellini (2000): Chapters 3 and 5 for an overview of the respective fundamental literature on party competition. The

current paper is not the right place to discuss the impact of ideology, what it means or where and it comes from.

3

The literature on the partisan theory has become much more comprehensive during the last decades, of course (see,

e.g., Alesina et al. (1997)). We just highlighted the beginnings but still highly relevant papers of the debate.

4

Niklas Potrafke

each veto player) of these players. However, this is just the one side of the coin. The second

effect claimed by most recent applications points out that policy stability increases with the

number of veto players (Tsebelis (2002)). There might be a lock-in effect: Countries with more

veto players have consistently low or, consistently high deficits. Stability might increase with the

number of coalition partners. Overall, the final impact remains as an empirical question. As

coalition partners also have to find agreements how they will spend their revenues, we expect that

the type of government, namely the number of coalition partners as well as the fact if the ruling

government has a majority in parliament (minority government) affect the budget composition.

Beyond this, we will not discuss other impacts and interactions4 any further. For example,

national political influences on economic issues might be mitigated due to globalization etc.

Garrett (1998: Chapter 2) discusses in detail how domestic policy might work in the global

economy. Potrafke (2007a) explicitly examines the interaction of government ideology and

globalization and tests its impacts on social expenditures. However, the current paper focuses on

national policy. Another caveat against the application of the respective theory to the budget

structure might be that newly-elected governments are not able to change the current budget.

Tsebelis and Chang (2004: 457 f.) provide a convincing discussion, why the current government

is responsible for the realization of the budget because it has the means to alter the existing

budget: First, finance ministers in most EU countries (the exceptions being Finland, the

Netherlands, Spain and Sweden) can either block expenditure or impose cash limits. They also

have the power to allow funds to be transferred between chapters, and the disbursement of the

budget in the implementation stage is subject to finance ministers approval. Second, there is a set

of formal rules that enables governments to deal with unexpected expenditure and revenue

shocks

2.2 The political economy of the budget composition

This subsection supports the application of the theories listed above on the budget composition

by presenting already existing theoretical models as well as empirical evidence on particular

expenditure categories. Bruninger (2005) offers a partisan model of government expenditure. He

assumes that for electoral reasons partisan actors generally prefer more spending to less but also

experience electoral costs from higher experience due to the increasing tax burden. Further, he

wants to emphasize the distinction between the ideological identity of governmental actors and

4

Interactions between the ideological party composition of the government and the number of coalition partners

could be considered in more detail. But then, the judging of respective coalition types becomes much more

complicated and further assumptions have to be made. Tsebelis and Chang (2004) create multidimensional indices in

their veto player model. These indices also take into account the ideological distances between the parties in each

government.

5

Niklas Potrafke

their programmatic policy and spending preferences. Two approaches are considered: A median

legislator model and a veto player model. Basically, the model predicts that the higher spending

preferences of the political actors for a certain issue, the higher will indeed be the real spending.

Drazen and Eslavas (2005) model of the political budget cycle focuses on the electoral effects.

Technically, the idea of targeted expenditures is close to earlier work from Lindbeck and Weibull

(1987) and Dixit and Londregan (1996). First, voters have different preferences regarding the

types of spending. The same holds for the politicians. But the latter might shift the composition

of the spending towards the goods voters prefer. Thereby, the politicians could signal that their

preferences are close to those of the voters, implying they will choose high-post election

spending on the same goods. In equilibrium, a political budget cycle will exist, in which: 1)

expenditures targeted to voters are expected to be higher in an election than a non-election

period; and 2) swing voters will rationally vote for an incumbent who provides higher targeted

expenditures even though they know that such expenditures may be electorally motivated

(Drazen and Eslava (2005: 14)). Considering the framework of asymmetric information about the

electoral environment, the model predicts even more room for the politicians to influence the

outcome of elections by providing more targeted expenditures prior to elections.

All-embracing hypotheses regarding the detailed way of allocating the expenditures by different

parties are not easy to formulate. It is simply impossible to classify all the COFOG expenditure

categories regarding these variables. Also Drazen and Eslava (2005: 3) state: Obviously a

classification of government expenditure into targeted and non-targeted expenditures is not

readily available or straightforward. However, more concrete hypotheses might be necessary

because of fundamental reasons in empirical work. Further, referring to Bruninger (2005) and

Drazen and Eslava (2005) the categories might be grouped regarding items of leftist and

rightwing governments as well as targeted to the median voter. But the current paper will test for

ideological (leftist versus rightwing) and election year effects (affecting the median voter)

together. Hence a grouping regarding both effects will be difficult. In addition, some types of

expenditure are more (in)elastic than others and may be subject to long run contracts, e.g.,

defence.

There is further literature on the impacts of political determinants on single expenditure

categories. Boix (1997) claims that leftist governments are expected to spend more on education

than conservative governments. He lastly concludes from his empirical analysis from 1970 to

1989 that a great deal of public spending on education is driven by demand factors mainly

the demographic structure of the country (Boix (1997: 835)). There were partisan effects

6

Niklas Potrafke

regarding public spending on education in the sixties and eighties but not in the seventies. Hicks

and Swank (1992) provide theory and evidence how policy influences welfare spending in

industrialized countries. For example, following the social democratic corporatist perspective,

leftwing and center (non-rightwing) party leadership of government generates higher welfare

effort than rightwing and intermediate party leadership. Leftist governments might even be

pressured to moderate prowelfare policies by the opposition. They further explore the hypothesis

that preelection welfare effort tends to exceed postelection effort (Hicks and Swank (1992: 659

f.)). Further empirical evidence detects higher social expenditures under leftist than rightwing

governments till the end of the cold war in 1990, but more responsibility in the 90ies (e.g.,

Kittel and Obinger 2003, Potrafke 2007a, Dreher 2006b does not find significant effects in the

period from 1970 to 2000). Nincic and Cusack (1979) examine the political economy of US

military spending and find an electoral cycle with higher military expenditures before elections.

Correa and Kim (1992) provide an overview of the literature on defence expenditure in the USA

and the USSR and conclude referring to the literature as well as their own empirical research that

defence expenditures in the USA are driven by political variables. They even find higher defence

expenditures under democratic presidents but admit that this finding contradicts the position

usually attributed and could change if a longer time period were included in the analysis

(Correa and Kim (1992: 168)). Leftist and rightwing governments might also have different

spending preferences regarding health. Immergut (1992: 1) states: National health insurance

symbolizes the great divide between liberalism and socialism, between the free market and the

planned economyPolitical parties look to national health insurance programs as a vivid

expression of their distinctive ideological profiles and as an effective means of getting

votesNational health insurance, in sum, is a highly politicized issue. Hence we further expect

higher public health expenditures under leftist than rightwing governments. Potrafke (2007b)

analyses an OECD panel and confirms this claim for the period from 1970 to 1990. However,

things change in the period from 1991 to 2004.

We will formulate hypotheses for these (core-) categories for which mappings with respect to the

single theories seem to be clear-cut and leave open the others. Thus Table 1 already presents the

different categories of public expenditure (COFOG) and easily acts as link to the next section.

The signs + and indicate an expected increasing or decreasing effect of the political

variables on the categories, respectively.

Table 1 about here

Niklas Potrafke

3. Data

3.1 Two data sets

There is no unique data set available yet, that classifies public expenditures of the general

government by so called COFOG (Classification of the Functions of Government) functions and

types for a longer time period, e.g., from 1970 till present. Therefore, we examine two different

data sets classifying public expenditures of the general government5: The one composed and used

by Sanz and Velzquez (2007) and Gemmell et al. (2007) covering the period from 1970 to 1989

as well as the recent data sets from the OECD for the period from 1990 to 2005. The first one

contains yearly data for 23 OECD countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark,

Finland, France, Germany6, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New

Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the USA (balanced panel).

The second data set from the OECD contains yearly data for the total expenditure structure of

13 OECD countries from 1990 to 2005. The panel is unbalanced. There are yearly data available

for Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the UK as well as the USA for the period

from 1990 to 2005. Data for Germany are available from 1991 to 2005, for Italy from 1990 to

2004. Austria, France and Sweden can be included with data running from 1995 to 2005. Lastly,

there are data for Japan from 1996 to 2005.7 Further, we will not consider any country with fewer

observations, so that at least some variation in time elapsed is mirrored and policy changes might

occur.

The examined data are public expenditures classified by so called COFOG in both cases, but

however, they differ in some respects. First, Sanz and Velzquez (2007) combined the two

categories of the original classification General public services and Public safety and order to

one category named Public services. We proceed in the same way for the second data set from

1990 to 2005 to make the results somewhat comparable. Hence this expenditure category refers

to the provision of publicly provided goods. Second, the new OECD classification includes a

category called Environmental protection.8 This differs from previous classifications so that

this category is not included in the data set by Sanz and Velzquez (2007). Instead Sanz and

Velzquez (2007) split Transport and communications from Economic Services because

Transport and communications are a kind of investment. Hence overall, both data sets

5

The data refer to the general government. Hence, we do not distinguish between the different jurisdictions in the

single countries and take the institutional background into account as Shelton (2007) and Potrafke (2006) do.

6

Germany will be excluded in our basic regressions because of missing data on some control variables. Section 5.3

will point out that our inferences are not sensitive to this exclusion.

7

There are also data for South Korea from 1996 to 2005. However, South Korea is a presidential system, so that the

current analysis of the political variables is not applicable.

8

Most of the expenditures for Environmental protection were classified via Housing due to the former

categorization.

8

Niklas Potrafke

distinguish between nine different expenditure categories where eight of them are named the

same in both data sets. Lastly, both data sets exclude interest payments. We will use the different

expenditure categories as dependent variables for the examination of the allocation of

expenditures across the countries. The appendix contains a detailed description of the single

expenditure categories due to the classification system and descriptive statistics9 of all variables.

3.2 Time series properties

The time series properties of the single variables emerge as very crucial for the econometric

specifications. The inclusion of non-stationary variables in the model might cause spurious

regression. Testing for stationarity of the time series, we apply a battery of panel unit root tests.

The advantage of the panel unit root tests compared to the univariate counterparts is to gain

statistical power. However, the tests to a panel also relate to asymptotic theory and therefore lose

power in small samples. Breitung and Pesarans (2005) overview on unit roots and cointegration

in panels points out that the respective tests refer to samples where the time dimension (T) and

the cross section dimension (N) are relatively large. However, we will carefully apply the battery

of respective tests, but will also stress that the results should be handled somewhat carefully due

to the small sample sizes. The appendix provides our several test results in detail and comments

on the chosen procedures. In conclusion, we will estimate the model in first differences.

4. The empirical model

As all categories described sum up to total expenditure and the government has to choose for

what it will spent its resources, it seems quite obvious that the expenditures for the single

categories are correlated with each other. This correlation between disturbances from different

equations at a given time is known as contemporaneous correlation (Judge et al. (1988: 443 ff.)).

The method of seemingly unrelated regression estimation (SURE) controls for this

contemporaneous correlation and provides efficient estimates (going back to Zellner (1962)). It is

also applicable in the given panel data framework. Therefore, we consider the following structural

SURE model with 10 equations to test for the impact of the political variables:

log Public expenditure categoryijt = k k Political variable ikt + l l log Xilt + ut

with j = 1,, 10; k = 1,,5; l=1,,8

(1)

Note that Spain, Portugal and Greece became democracies in the mid seventies. This explains the somewhat

smaller sample size of our political variables.

9

Niklas Potrafke

where the dependent variable log Public expenditure categoryijt denotes the first differences of

the change in expenditure category j as a share of GDP. We distinguish between nine expenditure

categories and also consider total spending as a further equation, so that there are ten equations

in total. Political variableikt introduces the political variables, on which this study focuses. The

next paragraph describes its coding in some more detail. l log Xilt contains eight exogenous

control variables as well as a constant. We follow the related studies to include: The first

differences of the change in total population, in the share of the young population (aged 14 and

below as a share of total population), in the share of the elderly population (aged 65 and above as

a share of total population), in per capita income (in real terms), in trade as share of GDP, in

prices of public consumption (Tridimas (2001)), as well as in the unemployment rate. Lastly we

also include the lagged dependent variable.

Political variableijt is in the centre of our analysis. We distinguish between a variable controlling

for the effect of election years, the ideological party composition of the governments, the number

of coalition partners, the fact if the respective governments had a majority in parliament or not

(minority government) as well as an interaction term of the ideology variable and the minority

government dummy.

The variable Electionit takes the exact timing of the elections into account. Following Franzese

(2000) and the application of De Haan and Mink (2005), it is calculated as

Electionit = [(M-1) + d/D]/12

where M is the month of the election, d is the day of the election and D is the number of days in

that month. In non-election years, its values are set to zero. Therefore, we directly control for

fluctuations and the fact that the election dates differ between as well as in the single countries.

An important challenge for the partisan test in an OECD panel is the heterogeneity of the parties

and parliamentary systems in the single states. Hence the question comes up what kind of

government could be labelled leftwing or rightwing especially when there are more than two

parties in government with different ideological roots. Bjrnskov (2005a: 4) concludes on this

issue: Political ideology is a potentially complex feature yet operationalizing it as a

unidimensional construct measurable in a left-to-right scheme hence need not necessarily entail

any sizeable loss of information or sophistication when connected to real political outcomes.

Researchers often use the index by Budge et al. (1993) and updated by Woldendorp et al. (1998)

10

Niklas Potrafke

and (2000) as a measure of the governments ideological positions.10 It locates the cabinet on a

left-right scale with values between 1 and 5. It takes the value 1 if the share of rightwing parties in

terms of seats in government and their supporting parties in parliament is larger than 2/3, 2 if it

is between 1/3 and 2/3. The index is 3 in a balanced situation if the share of centre parties is 50

per cent, or if the leftwing and rightwing parties form a government together not dominated by

one or the other side. Corresponding to the first two cases it takes the values 4 and 5 by a

dominance of the leftist parties likewise defined. Following this procedure, Potrafke (2007a)

applies an ideological index for a group of 20 OECD countries in the period from 1980 to 2003.

It is extended for the current analysis. Consequently, we get a uniform quantitative measure.

Finally, we label years in which the government changed corresponding to the one that was in

office for the longer period, e.g., when a rightwing government followed a leftist in August, we

label this year as leftist. Note that the coding of the ideology variable implies a positive impact on

public expenditures favoured by the left.

Moreover, the type of government is tested by two variables. Roubini and Sachs (1989)

constructed an index of power dispersion which distinguishes between the number of coalition

partners as well as if the government was a minority government. Unfortunately, this procedure

mixes the quantitative feature of the number of parties in the coalition with a qualitative feature,

namely if this government has a majority in parliament or not (Edin and Ohlsson (1991), De

Haan and Sturm (1994, 1997)). Therefore, we first install a variable controlling for the number of

parties in government. It ranges from 0 (no coalition) to 2 (huge coalition):

0 one-party majority parliamentary government;

1 coalition parliamentary government with two-to-three coalition partners;

2 coalition parliamentary government with four or more coalition partners.

Further we use a simple dummy variable to control for the impact of minority governments. It

takes on the value 1 when the government does not have a majority in parliament and zero

otherwise.

Moreover, the impact of the ideological government orientation might be mitigated when the

governments do not have a majority in parliament. They are dependent on the goodwill of other

10

Note that Bjrnskov (2005b) recently introduced a further cross-country indicator of political ideology for the

period from 1976 to 2000. It refers to the data base by Beck et al. (2001) and places the parties on a discrete left-toright scale where left parties are assigned the value -1, center parties 0 and right parties 1. Lastly the value of the

government ideology gt is the weighted sum of the respective ideologies of the three largest parties in government.

11

Niklas Potrafke

parties in parliament and therefore cannot implement their pure ideology. We control for this

effect by including the interaction term of our ideology variable and the minority government

dummy.

Lastly, we comment on the specialties regarding the estimation procedure. Taking first

differences of the levels due to stationarity reasons eliminates time-invariant fixed country effects.

Hence, the common least squares dummy variable estimator (fixed-effects) could be useless. But

there could also be linear time trends in each country. Hence, after first differencing, they appear

as time-invariant country effects in the model. Thus, it might also be sensible to apply fixed

country effects on the model in growth rates. Note further, that the constant included in our

regressions does not contradict estimating fixed country effects. The fixed effects are

implemented by simple country dummies and there is one dummy excluded in each regression to

avoid multicollinearity problems. However, in the context of a dynamic model specification using

the lagged dependent variable as regressor, the common fixed-effect estimator might be biased.

We cannot solve this problem in the SURE framework. But there are panel estimators that

correct for this problem. As Behr (2003) states, the estimators taking into account the resulting

bias can be grouped broadly into the class of instrumental estimators and the class of direct bias

corrected estimators. In accordance with large sample properties of the GMM methods, e.g., the

estimator proposed by Arellano and Bond (1991) will be biased in the current framework with N

= 23 or less. That is why bias corrected estimators might be a good choice. Bruno (2005)

presents a bias corrected least squares dummy variable estimator for dynamic panel data models

with small N. Hence we will also apply Brunos (2005) bias corrected estimator when fixed

country effects are present as a reference. This procedure is less efficient than SURE because it

does not correct for the contemporaneous correlation. We therefore face the tradeoffs between

potential bias and efficiency similar to the related literature.

5. Results

5.1 The period from 1970 to 1989

The distinction between the two subperiods from 1970 to 1989 and from 1990 to 2005 is first

caused by the availability of the data (section 3). However, as regards content, there is also an

important reason distinguishing between the time before 1990 and afterwards. This is highly

motivated by historical events. In 1990, there was the fall of the Iron Curtain; the end of the

Cold War arose in these years. Garret (1998: 1) states that one should be recitent to

conclude differently about the 1990s because of the highly idiosyncratic nature of the decade in

Europe. In addition, the nineties were also claimed as the end of the welfare states. Hence, the

12

Niklas Potrafke

historical background provides good reasons to examine respective sub-periods. Previous

research has shown empirically that there were differences between the 80ies and the 90ies (e.g.,

Kittel and Obinger (2003), Potrafke (2007a)).

Tables 2 and 3 about here

The estimation results in Table 2 refer to a SURE model with fixed country effects for the period

from 1970 to 1989. We first checked a fixed country effect versus a pooled regression. An F-Test

that all the fixed country effects are zero could be rejected at a 1 percent significance level.

Moreover estimating SURE and OLS would be equal, if there would be no contemporaneous

correlation between the single equations (or completely the same regressors in every equation are

used)11. The Breusch-Pagan-Tests for no contemporaneous correlation can be strongly rejected.

Hence, there are strong efficiency gains from using SURE in the considered model. Of the

contents, the expenditures in one category are dependent on the expenditures in the other

categories, as expected. F-Tests on the control variables point out that they are all jointly

significant at convenient levels except for the elderly share. Table 3 also shows the regression

results for the single equations using Brunos (2005) dynamic bias corrected estimator.12

Tables 2 and 3 point out that politicians increased spending for Health and Education as

well as for the overall public sector in election years. Hence we would conclude that they behaved

opportunistically and focused on the interests of the median voter to become re-elected. But the

impact of the electoral effects might depend on the fact if the election dates are predetermined;

that is if the particular elections were part of the regular electoral cycle or if they were irregular.

Shi and Svensson (2006) examine political budget cycles and point out that the election timing

might be endogenous. They argue that both timing of elections and fiscal policies could be

influenced by a number of variables, which are not included in the regression. This might cause

omitted variable bias. Mitigating this potential problem Shi and Svensson (2006) provide a

sensitivity analysis focusing on elections whose timing is predetermined relative to current fiscal

policies. Their results do not change for their whole sample but for developed countries. Brender

and Drazen (2005) argue that there are two conceptual problems with Shi and Svenssons (2006)

presumption. First, it may not be that obvious to distinguish between systems in which electoral

dates are fixed and systems where early elections may be called. In the same manner, early

11 Note

that in the current model the equations differ by the lagged dependent variable.

(2005) estimator can be used in relation to different intitial dynamic panel data estimators. The current

results refer to the Arellano-Bond (1991) estimator as initial one and standard errors are bootstrapped using 200

repetitions.

12 Brunos

13

Niklas Potrafke

elections seem to be the rule rather than the exception. Furthermore, there are countries where

the government may call early elections, but rarely does. Second, there is no clear theoretical

presumption about whether fiscal manipulation will be stronger or weaker when election dates

are effectively predetermined (Brender and Drazen (2005: 1282)). However, Brender and

Drazen (2005) also control for predetermined elections and find that results are not much

affected. In conclusion, as regards contents, distinguishing between regular and irregular elections

seems very reasonable. Thus, we will also consider it in the current paper. We applied Shi and

Svenssons (2006) data on the predetermined and endogenous election years from 1975 to 1995.13

Furthermore we extend the respective data from 1970 to 197414 and from 1996 to 2005 using the

Political Handbooks, following Shi and Svenssons (2006: 1374) rules. An election is classified to

be predetermined if either (i) the election is held on the fixed date (year) specified by the

constitution; or (ii) the election occurs in the last year of a constitutionally fixed term for the

legislature; or (iii) the election is announced at least a year in advance. Overall, we detect 63.8

percent of the elections as pre-determined.

Tables 4 and 5 about here

Tables 4 and 5 point out that the conclusion on the electoral cycle was spurious. In fact, the

positive effect of election years on the overall public sector size, expenditures on health and

education were driven by endogenous elections. The pre-determined election year variables

turned to be insignificant at convenient significance levels. It is implausible that politicians could

exploit the endogeneous elections for short-dated spending policies. They might not pass an

additional budget when early elections are announced. Thus, we cannot conclude that there is

evidence for an opportunistic behaviour of politicians in the period from 1970 to 1989.

Regarding the interpretation of the other policy variables we will refer to the results given in

Tables 4 and 5. The results report that leftist governments did not significantly extend the overall

public sector but allocated public expenditures differently compared to rightwing governments

till the end of the 80ies. They set other priorities. Note that the political effects are somewhat

weaker in the regressions of the single equations. As expected, they increased money for Public

services and therefore afford more publicly provided goods than rightwing governments.

Moreover, they disbursed more for Transport and communications (SURE), Housing and

13

We thank Min Shi and Jakob Svensson for providing their data.

Note that even the Political Handbook from 1976 does not exactly identify the general elections in Finland and

Japan 1972 as well as the election in Canada in 1974 as endogenous. They are highly expected to be endogenous, but

theoretically, they could have been announced one year in advance. Then we would have to label them as

predetermined. However, this would not affect our inferences.

14

14

Niklas Potrafke

Health. Thereby leftist governments seemed to gratify their clientele. However, we expected

leftist governments to spend less for Defence and more for Social welfare. The results do

not fulfil these prospects. But they might also reflect the fact that the influenced expenditures are

more elastic in the short run and not subject to long run contracts like, e.g., defence.

Moreover, the ideology effects were mitigated when the respective governments did not have a

majority in parliament. Therefore the respective marginal effects of the ideology variables and

their significances have to be interpreted conditional on the interaction with the minority

government dummy (see Friedrich (1982)). In principle, there are two sensible ways to evaluate

the marginal effects. Dreher and Gassebner (2007) suggest evaluating them at the minimum as

well as the maximum of the interacted variable. This procedure also emerges as sensible in our

case as the minority government variable is a dummy facing the values 0 and 1. Hence in case of

a majority government the marginal effect just equals the coefficient of the ideology variable

itself. Its meaning is that a corresponding increase of the ideology variable by one point say

from 3 (leftist and rightwing parties in government) to 4 (leftwing government) would increase

the growth rate of public expenditures for Public services by 1.5, the one for Transport and

communications by 1.7, the one for Housing by 3.5 and the one for Health by 0.9 percent

(SURE model in Table 4). We further calculated the marginal effects for the case when the

minority variable is 1. Then, all the marginal effects are statistically insignificant. Thus our results

imply that the hypothesis that parties matter is only fulfilled when they had a majority in

parliament. Without a majority, they were not able to implement their ideological preferences and

to set respective priorities regarding the budget composition. This result confirms an extremely

plausible expectation. In principle, the marginal effects could also be calculated on an average

level of the variable the one of interest is interacted with, but this does not seem sensible

examining the interaction with a simple dummy variable.

Moreover, the results do not allow drawing any conclusions regarding the impact of the size of

coalition variable. It is insignificant in every single equation. Referring to the SURE model, we

further applied F-Tests on the political variables checking their joint significance. F-Tests are

important because they consider the correlation structure between the single parameters and it

could be that all the single coefficients are insignificant in the single equations but jointly

significant.15 Table 6 provides the results. They report that the ideology and minority government

variables are jointly significantly different from zero at 5 or rather 10 percent level.

15

Geometrically, the confidence intervals of the single parameters can be drawn as line segments, whereas the joint

confidence intervals (confidence region) can look like an ellipse. (See, e.g., Judge et al. (1988): 244 ff.).

15

Niklas Potrafke

Table 6 about here

Our results fit the previous literature in the sense that leftist governments did expansionary

policies compared to rightwing governments till the end of the 80ies. As Potrafke (2007b) we

find higher expenditures for Health. Furthermore, the current results do not contradict the

recent literature on social expenditures (e.g., Kittel and Obinger (2003) and Potrafke (2007a))

under leftist governments in this period, because our current results do not report a significant

positive impact of leftist governments on Social welfare. Note that social expenditures include

spending for health and also housing, for which we got positive effects in our current regressions.

5.2 The period from 1990 to 2005

Table 7 provides the results relating to the panel from 1990 to 2005. They indeed differ from the

results referring to the period from 1970 to 1989. Policy had weaker impacts. In contrast to the

previous model, the F-Tests do not reject the hypothesis that fixed country effects are zero.

Hence we estimate a SURE model with a common constant only. There cannot be a Nickel-bias.

F-Tests on the control variables point out that the three population variables are jointly

insignificant. However, we follow the related literature and keep them in the model. As before,

we first refer to the results with the simple election year variable (Table 7). Politicians seemed to

increase spending for Health before elections. There are no further election year effects. Table

8 shows the respective results with predetermined and endogenous elections and points out that

the electoral effect on public health expenditures was only due to endogenous elections. This

finding perfectly corresponds with Potrafke (2007b). Moreover, we detect different spending

preferences of leftist and rightwing governments. At first, parties did not affect the overall

Public sector size. Then the results show higher spending for Cultural affairs and

Education and lower spending for Social welfare under leftist governments in the period

from 1990 to 2005. These effects only hold when the respective government had a majority in

parliament. We again calculate marginal effects which are statistically insignificant when the

minority dummy is equal to one. Higher spending for Education under leftist governments

fulfils our expectations whereas lower spending for Social welfare does not. Also previous

research (e.g. Kittel and Obinger 2003, Potrafke 2007a) has shown that leftist governments did

not implement expansionary policies in the nineties, however, negative impacts are not in line

with the implications of the partisan approach. Moreover, the results do not support the

expectation of higher expenditures for Housing and Health under leftist and also higher

spending for Defence under rightwing governments. The size of coalition did not influence the

16

Niklas Potrafke

budget composition specifically. The results of the F-Tests on the political variables in Table 9

point out that there are no joint significant effects.

The results do not provide evidence for a policy change regarding a particular spending category.

In other words, we do not find statistical significant effects with different size or even sign of a

variable comparing the regressions from 1970 to 1989 and the ones from 1990 to 2005.

Tables 7, 8 and 9 about here

5.3 Robustness of the results

The robustness of the results must be checked in several ways. At first, we will discuss another

econometric specification using somewhat different control variables. The results of Tables 10,

11 and 12 refer to regressions in which we changed three different features. First we also include

the sum of the other expenditures as explanatory variable (i Expenditure Categoryij). The

expenditures for category j must be excluded to avoid endogeneity problems. Hence, the model

controls for the general spending behaviour and implied allocation effects in each equation.

Second, the previous regressions included trade as a share of GDP as it is common in the related

literature. In principle, this could cause endogeneity problems because the dependent variable is

also measured as a share of GDP. Therefore we apply a different measure for trade that also

takes into account the relative size of the respective country or rather economy by including trade

per capita (sum of imports and exports divided by population). Third, the demographic change

could also be considered by the share of the working population. We therefore replace the shares

of the young and the old by population aged between 15 and 64 as share of the population.16

Tables 10, 11 and 12 about here

Tables 10 and 11 report the robustness of our results and inferences regarding the political

effects on the budget composition in the period from 1970 to 1989. F-Tests of the political

variables also support our findings. The negative impact of leftist governments on Social

welfare in the period from 1990 to 2005 turned slightly insignificant (Table 12).

Moreover, we replaced trade as measure of openness or rather globalization by the KOF index of

globalization (Dreher (2006a) and Dreher et al. (2008)). The inclusion of the overall as well as the

16

We choose this variable instead of the dependency ratio which describes the ratio between those of working age

and those of non-working due to data availability for all the countries from 1970 to 2005.

17

Niklas Potrafke

three sub indices does not affect our inferences regarding the political variables. Interestingly, we

find negative impacts of the KOF index of economic globalization on the budget composition

from 1970 to 1989.

General government debt might also be an interesting explanatory variable. However, there is the

problem of data availability for the time period from 1970 to 1989 in an OECD panel. The

inclusion of general government debt as a share of GDP results in a regression with 209

observations. In this sample, the positive impact of leftist governments on expenditures for

Transport and communications and Health turns to be statistically insignificant. Instead,

there is a statistical negative impact of leftist governments on Education. Regarding the panel

from 1990 to 2005, the inclusion of public debt does not change our inferences at all. Leftist

governments still affect spending for Cultural affairs, Education and Social welfare as

before.

The regressions in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 and 11 referring to the period from 1970 to 1989 only

cover 22 OECD countries. Germany is excluded because there are no data on public

consumption prices available till the beginnings of the nineties. Hence we were running

regressions using consumer prices instead of public consumption prices because there are also

data for Germany available. These regressions show that our results presented above are not

sensitive to the exclusion of Germany. They further point out that education was a polarizing

political issue in Germany in the seventies and eighties in the sense that leftist governments spent

more for education than rightwing governments. These empirical results indeed fit anecdotal

evidence on the spending preferences of the Social Democrats ruling in Germany from 1969 to

1982.

The differences between the two data sets due to their number of countries covered as well as the

measurement of the single expenditure categories (recoding) might be a caveat against our

conclusion on a policy change with the beginnings of the nineties. Therefore we estimate two

further models countervailing this appeal. First, we only focus on the same 13 countries for the

period from 1970 to 1989 for which we also have data for the period from 1990 to 2005. In this

sample, the policy effects are indeed weaker. Note for example, that especially health is a

polarizing political issue only in some countries like e.g. Australia and New Zealand (Potrafke

(2007b)). But these two are not included in the 13 country panel. Hence the inferences from the

panel referring to only 13 countries might be somewhat selective. Second, we were also running

regressions using the data from Sanz and Velzquez (2007) and Gemmell et al. (2007) for the

18

Niklas Potrafke

period from 1970 to 1997. In this scenario, the policy impacts are indeed weaker than focusing

on the 70ies and 80ies. These findings strongly support a policy change with the beginnings of

the nineties. However, the question remains if there was a structural shift that also affected the

parties and therefore our political variables itself. In other words, we simply applied a static

ideology variable which does not consider that also parties change in time elapsed. They simply

might have changed their preferences. Potrafke (2007c) develops a procedure for the

construction of a dynamic ideology index and applies it to German data. It exactly controls for

this shortcoming.

As it is common in the literature, we check for the sensitivity of the results to individual

countries. Therefore, we rerun the regressions excluding one country at a time. Some of the

results are sensitive to the inclusion of particular countries. Regarding the first data set, the

impact of the ideology variables strongly declines when New Zealand is excluded. Also, excluding

Australia turns down the impact of the ideology variable on expenditures on Health. Leftist

governments in the USA spent much more for Public services than rightwing governments.

Denmark, Spain and Sweden are countries in which minority governments were in power. Not

surprisingly, the impacts of minority governments are strongly driven by these countries.

Regarding the OECD panel from 1990 to 2005, excluding Belgium, Japan, the UK and the USA

weakens the impacts of the ideology variables. Interestingly, the USA mainly drives the negative

effect of leftist government on Social protection.

6. Conclusion

This paper showed how political effects determined the allocation of public expenditures (general

government) in OECD countries from 1970 to 2005. Examining policy impacts on the budget

composition requires a detailed expenditure composition because the broader the classification

the higher the probability of compensating policy effects. Therefore, we focused on the COFOG

classification with 9 different subcategories. As there is no comprehensive data set available yet,

we analyzed two different ones: The data set collected by Sanz and Velzquez (2007) and

Gemmell et al. (2007) for the period from 1970 to 1989 as well as current data from the OECD

for the period from 1990 to 2005. Our results demonstrated that there were strong policy effects

in the first period. In line with the expectations, leftist governments disbursed more than

rightwing governments for Public services, Transport and communications, Housing and

Health. But interestingly, we did not detect a statistically significant effect on total government

spending. This finding highly fortified the aim of the current paper examining the allocation of

19

Niklas Potrafke

public expenditures because there might even be compensating effects between the categories.

Moreover, we controlled for the interaction between government ideology and minority

governments. Our results clearly demonstrated that parties did only matter when they had a

majority in parliament. Lastly, applying the distinction between predetermined and endogenous

election year effects introduced by Shi and Svensson (2006), we indeed detected the electoral

effects as spurious.

Effects were different using the current OECD data set from 1990 to 2005: The political impacts

of the budget composition became weaker. Furthermore, parties set other priorities in the sense

that leftist governments increased spending for Cultural affairs and Education and even

decreased for Social welfare. In conclusion, our analysis pointed out that there was a policy

shift. This change was not only due to the different data sets. However, more detailed inferences

would require a comprehensive data set.

Therefore the results of the current paper provide two important implications for future research.

First, dynamic policy variables especially ideology indices should be developed and applied in

empirical research considering the changes in time elapsed. Our results are perfectly in line with

the previous research in the sense that we detected a policy change with the beginning of the

nineties. Leftist governments did not do expansionary policies any more. However, it would be

interesting to examine if these policy changes are still present when the political variables also

take into account that parties change in time elapsed. Second, a comprehensive data set on the

budget composition (COFOG) seems to be very helpful for future research. Further research

might composite and examine a unique data set on the budget composition. Then we could

determine if our analysis of political effects as well as the results in the very recent literature on

the allocation of public expenditures (Dreher et al. (2007), Sanz and Velzquez (2007), Gemmell

et al. (2007) and Shelton (2007)) hold in a unique and extended data set. Moreover, one could

determine the most important driving factors on the allocation of public expenditures and further

test for their interactions.

20

Niklas Potrafke

Appendix: Panel unit root tests

The following tables report the results of the panel unit root tests on the government

expenditures as a share of GDP as well as the tests on the respective series of population, the

elderly and young share, per capita income, trade as a share of GDP, prices of public

consumption, the unemployment rate, the (population) share aged 15-64 and trade per capita for

the panel from 1970 to 1989 as well as for the panel from 1990 to 2005. They refer to the test on

the first differences. We applied the Levin et al. (2002), Im et al. (2003) and the Fisher tests

referring to Maddala and Wu (1999) and Choi (2001). In contrast, the Hadri (2000) test uses the

null hypothesis that there is no unit root. Breitung and Pesaran (2005) provide a detailed

description of the recent panel unit root tests. The results were obtained using Eviews 5.1. In

comparison to STATA 9.1, Eviews 5.1. allows to apply the respective tests on unbalanced panels,

it considers an automatic lag length selection by the use of Information Criteria and also contains

the Breitung (2000) test. Regarding the first three tests listed in the table, maximum lag lengths

are automatically selected based on the Schwarz Information Criterion. The remaining two tests

use the Bartlett kernel for the Newey-West bandwidth selection. The probabilities for the Fisher

tests are computed using an asymptotic Chi-square distribution. All other tests assume asymptotic

normality (See Hartwig (2007: Appendix)).

Tables 13 to 20 about here

Tables 13 to 20 report the results of different unit root tests and demonstrate that we can always

reject the null hypotheses of a unit root in first differences except for the elderly and young share

and prices of public consumption17 However, the Hadri tests indicate that regarding most of the

series, there are still unit roots in first differences. Overall, we conclude from these tests that the

time series in first differences are stationary. However, at first, we applied the respective tests on

the level series, of course. At this stage, the inclusion of a deterministic trend in the test

regression emerges as crucial. There are pros and cons to include linear time trends testing for

unit roots in time series in levels. Statistically, the plots of the series demonstrate their rise in time

elapsed. Furthermore including a trend is necessary so that the process can mirror the data under

the alternative hypothesis. This definitely demands the inclusion of linear time trends. As regards

content, one might argue that linear time trends must be excluded because the respective

variables cannot steadily increase, e.g., the rise of public spending could not be infinite. As a

17

Note that when the share of a respective category is zero in a single country (e.g., Defence or Cultural Affairs),

then Eviews 5.1. does not take into account this country because the logarithm of zero is not defined. In contrast, we

indeed consider these observations in our regressions by setting the first difference of the logarithm also equal to

zero.

21

Niklas Potrafke

result, we include a linear trend in the test regression in levels. Moreover, taking first differences

eliminates linear time trends so that we did not include them in the test regressions in first

differences. Overall, the tests on the levels mostly indicate that the respective series are nonstationary in levels. Therefore, we estimate the models in first differences. We take first

differences of all variables for consistency reasons, running the risk of over- or underdifferentiation of single variables.18

Finally, the applied battery of panel unit root tests is standard and fits the ones in the existing

literature. More sophisticated tests (as described in Breitung and Pesaran (2005)) do not seem

necessary in the current paper. In particular, so called second generation panel unit root tests

might be applied, that take into account the fact that the time series might not be independent

across i, but contemporaneously correlated. However, Breitung and Pesaran (2005: 19) claim that

the literature on modelling of cross section dependence in large panels is still developing. The

named tests suggest that estimating in first differences will be the best specification. Moreover,

one might put doubt on the inference of any unit root test due to the relatively small number of

observations in the sample. In this case, researchers might refer to their empirical intuition

specifying the model. We indeed strongly believe that using first differences is the most

appropriate way in the current framework.

18

Finally, the applied battery of panel unit root tests is standard and fits the ones in the existing literature. More

sophisticated tests (as described in Breitung and Pesaran (2005)) do not seem necessary in the current paper. In

particular, so called second generation panel unit root tests might be applied, that take into account the fact that the

time series might not be independent across i, but contemporaneously correlated. However, Breitung and Pesaran

(2005: 19) claim that the literature on modelling of cross section dependence in large panels is still developing. The

named tests suggest that estimating in first differences will be the best specification. Moreover, one might put doubt

on the inference of any unit root test due to the relatively small number of observations in the sample. In this case,

researchers might refer to their empirical intuition specifying the model. We indeed strongly believe that using first

differences is the most appropriate way in the current framework.

22

Niklas Potrafke

References

Alesina, A. 1987. Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. The Quarterly

Journal of Economics 102 (3), 651-678.

Alesina, A., Nouriel, R., Cohen, G. D. 1997. Political cycles and the macroeconomy. Cambridge:

The MIT Press.

Alt, J. E., Lassen, D. D. 2006. Fiscal transparency, political parties, and debt in OECD countries.

European Economic Review 50, 1403-1439.

Arellano, M., Bond, S. 1991. Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence

and an Application to Employment Equations. Review of Economic Studies 58, 277297.

Bawn, K. 1999. Money and majorities in the Federal Republic of Germany: Evidence from a veto

players model of government spending. American Journal of Political Science 43, 707-736.

Beck, T.,Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., Walsh, P. 2001. New tools in comparative political

economy: The database of political institutions. World Bank Economic Review 15, 165-176.

Behr, A. 2003. A comparison of dynamic panel data estimators: Monte Carlo evidence and an

application to the investment function. Discussion paper 05/03, Economic Research Centre of

the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Belke, A. 1996. Politische Konjunkturzyklen in Theorie und Empirie. Tbingen: Mohr-Siebeck

Verlag.

Belke, A. 1997a. Politischer Konjunkturzyklus Kritische Anmerkungen zum Erklrungsbeitrag

des Parteignger-Ansatzes. Ifo-Studien 3/1997 43, 311-346.

Belke, A. 1997b. Regierungsideologie, Geldpolitik und Persistenz der Arbeitslosigkeit,

Volkswirtschaftliche Diskussionsbeitrge der Ruhr-Universitt Bochum, Nr. 7, Bochum.

Belke, A. 1997c. Tests politischer Konjunkturzyklen vom Partisan-Typ: Problematik und

empirische Evidenz im Vergleich Deutschlands und der Vereinigten Staaten, RWI-Mitteilungen

47, 181-214.

Belke, A. 2000. Partisan political business cycles in the German labour market? Empirical tests in

the light of the Lucas-critique, Public Choice 104, 225-283.

Bjrnskov, C. 2005a. Political ideology and economic freedom. Working Paper 05-8, Department

of Economics, Aarhus School of Business.

Bjrnskov, C. 2005b. Does political ideology affect economic growth. Public Choice 123, 133146.

23

Niklas Potrafke

Boix, C. 1997. Political parties and the supply side of the economy: The provision of physical and

human capital in advanced economies, 1960-90. American Journal of Political Science 41 (3),

814-845.

Bruninger, T. 2005. A partisan model of government expenditure. Public Choice. 125, 409-429.

Breitung, J. 2000. The local power of some unit root tests for panel data. In: Baltagi, B. (Eds.),

Advances in Econometrics, Vol. 15: Nonstationary panels, panel cointegration, and dynamic

panels. JAI Press: Amsterdam; 1990, 161-178.

Breitung, J., Pesaran, M. H. 2005. Unit Roots and cointegration in panels. CESifo Working

Paper No. 1565.

Brender, A., Drazen, A. 2005. Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies.

Journal of Monetary Economics 52, 1271-1295.

Bruno, G. S. F. 2005. Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel data models with a

small number of individuals. CESPRI WP n. 165, Universit Bocconi-CESPRI, Milan.

Budge, I., Keman, H., Woldendorp, J. 1993. Political data 1945-1990. Party government in 20

democracies. European Journal of Political Research 24 (1), 1-119.

Choi, I. 2001. Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance 20 (2),

249-272.

Correa, H., Kim, J.-W. 1992. A causal analysis of defence expenditures of the USA and the

USSR. Journal of Peace Research 29 (2), 161-174.

De Haan, J., Mink, M. 2005. Has the Stability and Growth Pact impeded political budget cycles in

the European Union? CESifo Working Paper No. 1532.

De Haan, J., Sturm, J.-E. 1994. Political and institutional determinants of fiscal policy in the

European Community. Public Choice 80, 157-172.

De Haan, J., Sturm, J.-E. 1997. Political and economic determinants of OECD budget deficits

and government expenditures: A reinvestigation. European Journal of Political Economy 13, 739750.

Dixit, A., Londregan, J. 1996. The determinants of success of special interests in redistributive

politics. Journal of Politics 58, 1132-1155.

Drazen, A., Eslava, E. 2005. Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: Theory and

evidence. Working Paper. Tel Aviv University.

Dreher, A. 2006a. Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization.

Applied Economics 38 (10), 1091-1110.

Dreher, A. 2006b. The influence of gloablization on taxes and social policy an empirical

analysis of OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy 22 (1), 179-201

Dreher, A., Gassebner, M. 2007. Greasing the wheels of entrepreneurship? The impact of

regulations and corruption on firm entry. CESifo Working Paper No 2013.

24

Niklas Potrafke

Dreher, A., Gaston, N., Martens, P. 2008. Measuring globalization Understanding its causes

and consequences. Springer: Berlin, forthcoming.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., Ursprung, W. 2007. The impact of globalization on the composition of

government expenditures: Evidence from panel data. Public Choice. forthcoming.

Edin, P.-A., Ohlsson, H. 1991. Political determinants of budget deficits: Coalition effects versus

minority effects. European Economic Review 35, 1597-1603.

Franzese, R. 2000. Electoral and partisan manipulation of public debt in developed democracies,

1956-1990, in: Strauch, R., von Hagen, J. (Eds.), Institutions, politics and fiscal policy.

Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Press, pp. 61-83.

Friedrich, R. J. 1982. In defence of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations.

American Journal of Political Science 26, 797-833.

Galli, E., Rossi, S. 2002. Political budget cycles: The case of the Western German Lnder. Public

Choice 110, 283-303.

Garrett, G. 1998. Partisan politics in the global economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Gemmell, N., Kneller, R., Sanz, I. 2007. Foreign investment, international trade and the size and

structure of public expenditures. European Journal of Political Economy. DOI:

10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2007.06.004

Hadri, K 2000. Testing for stationarity in heterogeneous panel data. Econometrics Journal 3 (2),

148-161.

Hartwig, J. K. 2007. What drives health care expenditure? Baumols model of unbalanced

growth revisited. Journal of Health Economics, forthcoming.

Hibbs, D. A. Jr. 1977. Political parties and macroeconomic policy. The American Political

Science Review 71, 1467-1487.

Hicks, A. M., Swank, D. 1992. Politics, institutions and welfare spending in industrialized

democracies, 1960-82. The American Political Science Review 86 (3), 658-674.

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y. 2003. Testing for roots in heterogenous panels. Journal of

Econometrics 115 (1), 53-74.

Immergut, E. M. 1992. Health politics Interests and institutions in Western Europe. Cambridge

University Press: Cambridge.

Judge, G. G., Hill, R. C., Grifftths, W. E., Ltkepohl, H., Lee, T.-S. 1988. Introduction to the

theory and practice of econometrics. New York a.o.: John Wiley & Sons.

Kittel, B., Obinger, H. 2003. Politicial parties, institutions, and the dynamics of social expenditure

in times of austerity. Journal of European Public Policy 10 (1), 20-45.

25

Niklas Potrafke

Knig, T., Trger, V. 2005. Budgetary politics and veto players. Swiss Political Science Review 11

(4), 47-75.

Levin, A., Lin, C. F., Chu, C. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample

properties. Journal of Econometrics 108 (1), 1-24.

Lindbeck, A., Weibull, J. W. 1987. Balanced-budget redistribution as the outcome of political

competition. Public Choice 52, 273-297.

Maddala, G. S., Wu, S. 1999. A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new

simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 61, 631-652.

Mueller, D. C. 2003. Public Choice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nincic, M., Cusack, T. R. 1979. The political economy of US military spending. Journal of Peace

Research 16 (2), 101-115.

Nordhaus, W. D. 1975. The political business cycle. The Review of Economic Studies 42 (2),

169-190.

Persson, T., Tabellini, G. 2000. Political economics Explaining economic policy. Cambridge:

The MIT Press.

Potrafke, N. 2006. Parties matter in allocating expenditures: Evidence from Germany. DIW

Discussion Papers No. 652.

Potrafke, N. 2007a. Social expenditures as a political cue ball? Empirical evidence from OECD

countries. DIW Discussion Papers No. 676.

Potrafke, N. 2007b. Public health expenditures in OECD countries: Does policy matter?

Humboldt University Berlin, mimeo.

Potrafke, N. 2007c. Parties change! The development of a dynamic ideology index and its

consideration in empirical research. Humboldt University Berlin; mimeo.

Rogoff, K., Sibert, A. 1988. Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. The Review of

Economic Studies 55 (1), 1-16.

Roubini, N., Sachs, J. D. 1989. Political and economic determinants of budget deficits in the

industrial democracies. European Economic Review 33, 903-938.

Sanz, I., Velzquez, F. 2007. The role of aging in the growth of government and social welfare

spending in the OECD. European Journal of Political Economy. DOI:

10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2007.01.003.

Shelton, C. A. 2007. The size and composition of government expenditure. Journal of Public

Economics; DOI:10.1016/jpubeco.2007.01.003.

Shi, M., Svensson, J. 2006. Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why?

Journal of Public Economics 90, 1367-1389.

26

Niklas Potrafke

Tridimas, G. 2001. The economics and politics of the structure of public expenditure. Public

Choice 106, 299-316.

Tsebelis, G. 1995. Decision making in political systems: Veto players in presidentialism,

parliamentarism, multicameralism and multipartyism. British Journal of Political Science 25, 289325.

Tsebelis, G. 2002. Veto players How political institutions work. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Tsebelis, G., Chang, E. C. C. 2004. Veto players and the structure of budgets in advanced

industrialized countries. European Journal of Political Research 43 (3), 449-476.

Weingast, B. R., Shepsle, K. A., Johnson, C. 1981. The political economy of benefits and costs: A

neoclassical approach to distribution politics. Journal of Political Economy 89, 642-664.

Woldendorp, J., Keman, H., Budge, I. 1998. Party government in 20 democracies: an update

1990-1995. European Journal of Political Research 33, 125-164.

Woldendorp, J., Keman, H., Budge, I. 2000. Party government in 48 democracies 1945-1998:

composition, duration, personnel. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Zellner, A. 1962. An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests of

aggregation bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association 57, 348-368.

27

Niklas Potrafke

Table 1. Expected effects of the political determinants on the expenditure categories

Expenditure Category

Public services

Defence

Economic affairs

Transport and communications

Environmental protection

Housing

Health

Cultural Affairs

Education

Social welfare

Election year

Leftist government

Type of government

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

28

Table 2: Regression Results. 1970-1989. Basic Scenario. SURE. Fixed Country Effects.

Election

Ideology

Size of coalition

Minority government

Ideology * Minority government

log Total population

log Young share

log Elderly share

log Per capita income

log Trade (as a share of GDP)

log Prices public consumption

log Unemployment

Lagged dependent variable

Constant

Observations

Number of countries

R-squared

F-Statistic

P-Value

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Public sector

size

Public services