Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoön: An Essay Upon The Limits of Painting An D Poetry (1766)

Încărcat de

Vera StankovTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoön: An Essay Upon The Limits of Painting An D Poetry (1766)

Încărcat de

Vera StankovDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Richard L. W.

Clarke LITS2002 Notes 12B

1

GOTTHOLD EPHRAIM LESSING,

LAOCOÖN: AN ESSAY UPON THE LIMITS OF PAINTING AND POETRY (1766)

Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim. Laocoon: an Essay Upon the Limits of Painting and Poetry.

Trans. Ellen Frothingham. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1874.

Chapter XVI

Here, Lessing summarises his basic argument, “starting from first principles” (). He contends

that “painting employs wholly different signs or means of imitation from poetry, — the one

using forms and colors in space, the other articulate sounds in time” (). If “signs must

unquestionably stand in convenient relation with the thing signified” (), then “signs arranged

side by side can represent only objects existing side by side, or whose parts so exist” (),

while “consecutive signs can express only objects which succeed each other, or whose parts

succeed each other, in tim e” (). “Objects which exist side by side, or whose parts so exist,

are called bodies. Consequently bodies with their visible properties are the peculiar subjects

of painting” (). “Objects which succeed each other, or whose parts succeed each other in

time, are actions. Consequently actions are the peculiar subjects of poetry” ().

Lessing points out, however, that all

bodies . . . exist not only in space, but also in time. They continue, and, at any

moment of their continuance, may assume a different appearance and stand in

different relations. Every one of these momentary appearances and groupings

was the result of a preceding, may become the cause of a following and is

therefore the centre of a present action. ()

Consequently,

painting can imitate actions also, but only as they are suggested through

forms. Actions, on the other hand, cannot exist independently, but must

always be joined to certain agents. In so far as those agents are bodies or are

regarded as such, poetry describes also bodies, but only indirectly through

actions. Painting, in its coexistent compositions, can use but a single moment

of an action, and must therefore choose the most pregnant one, the one most ,

suggestive of what has gone before and what is to follow. ()

By contrast,

Poetry, in its progressive imitations, can use but a single attribute of bodies,

and must choose that one which gives the most vivid picture of the body as

exercised in this particular action. ()

Hence, Lessing argues, the “rule for the employment of a single descriptive epithet, and the

cause of the rare occurrence of descriptions of physical objects” ().

Lessing believes that this “dry chain of conclusions” () is “fully confirmed by Homer” ()

or, least, was “first suggested to me by Homer's method” (). These “principles alone furnish

a key to the noble style of the Greek, and enable us to pass just judgment on the opposite

method of many modem poets who insist upon emulating the artist in a point where they

must of necessity remain inferior to him” (). Homer, Lessing argues, “paints nothing but

progressive actions. All bodies, all separate objects, are painted only as they take part in

such actions, and generally with a single touch” . Artists accordingly “find in Homer's pictures

little or nothing to their purpose” (), and their “only harvest is where the narration brings

together in a space favorable to art a number of beautiful shapes in graceful attitudes,

however little the poet himself may have painted shapes, attitudes, or space” (). Over the

course of the rest of the chapter, Lessing undertakes to “examine more closely the style of

Homer” ().

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Laocoon: An Essay upon the Limits of Painting and PoetryDe la EverandLaocoon: An Essay upon the Limits of Painting and PoetryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (23)

- Separation and Conjunction: Music and Art, Circa 1800-2010: Simon Shaw-MillerDocument24 paginiSeparation and Conjunction: Music and Art, Circa 1800-2010: Simon Shaw-MillerBlg RknÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viktor Shklovsky "Art As Technique" (1917) : Richard L. W. Clarke LITS3304 Notes 05ADocument3 paginiViktor Shklovsky "Art As Technique" (1917) : Richard L. W. Clarke LITS3304 Notes 05ANicole MarfilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russian FormalismDocument4 paginiRussian FormalismDiana_Martinov_694100% (1)

- As Device: Notes On The Theory of Literature He SaysDocument8 paginiAs Device: Notes On The Theory of Literature He SaysRaphael ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EkfrasisDocument15 paginiEkfrasisDiego A MejiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 03 A Shklovsky Art As TechniqueDocument3 pagini03 A Shklovsky Art As TechniqueJudhajit SarkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of ImitationDocument2 paginiTheory of ImitationBrince Mathews75% (4)

- AristotleDocument14 paginiAristotleSourabh Agarwal100% (1)

- Lessing's Laocoon: Aesthetics, Affects and Embodiment: Cecilia SjöholmDocument16 paginiLessing's Laocoon: Aesthetics, Affects and Embodiment: Cecilia SjöholmHai WangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romantic Age, ColeridgeDocument6 paginiRomantic Age, ColeridgeayishashhabazulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kushagr Singh-LD PDFDocument356 paginiKushagr Singh-LD PDFKushagr SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anna Szczepanek: Cubistic Techniques in William Carlos Williams' Ekphrastic PoetryDocument10 paginiAnna Szczepanek: Cubistic Techniques in William Carlos Williams' Ekphrastic Poetrystripes-in-my-headÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theorey of ImitationDocument3 paginiTheorey of Imitationjazib1200100% (1)

- Mimetic CriticismDocument3 paginiMimetic Criticismsumitdas98760Încă nu există evaluări

- Victor Shklovsky Art As A TechniqueDocument13 paginiVictor Shklovsky Art As A TechniqueIrena Misic100% (1)

- Article 1Document4 paginiArticle 1DeepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tiuchev Russian Metaphsysical Romantism1Document142 paginiTiuchev Russian Metaphsysical Romantism1Alessandra FrancescaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fifteen Years of Russian FormalismDocument5 paginiFifteen Years of Russian FormalismAlexis Manuel De SousaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adrienne Rich and John Ashbery: An Atlas On TraditionDocument12 paginiAdrienne Rich and John Ashbery: An Atlas On TraditionMidori Reyes ShiraiÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Ako Ang Daigdig" by Alejandro Abadilla: An AnalysisDocument3 pagini"Ako Ang Daigdig" by Alejandro Abadilla: An AnalysisJog YapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orientation of Critical TheoriesDocument6 paginiOrientation of Critical TheoriesSonali Dhawan100% (1)

- Lukacs, Dostoevsky, and The Politics of Art - Utopia in The Theory of The Novel and The Brothers KaramazovDocument11 paginiLukacs, Dostoevsky, and The Politics of Art - Utopia in The Theory of The Novel and The Brothers KaramazovmostafagordakhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formalism Refers To A Style of Inquiry That Focuses On Features of The Literary Text ItselfDocument5 paginiFormalism Refers To A Style of Inquiry That Focuses On Features of The Literary Text ItselfTeresa KawaÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Ashbery's SurrealismDocument16 paginiJohn Ashbery's SurrealismO993Încă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Poetry and Erza Pound ImagismDocument25 paginiChinese Poetry and Erza Pound Imagismtatertot100% (8)

- RAMOS - Delineating Art (Aristotle Da Vinci)Document5 paginiRAMOS - Delineating Art (Aristotle Da Vinci)Ica RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 0Document11 pagini1 0anasonadi234Încă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Meg5Document11 paginiAssignment Meg5anithafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metatheatre: A Theoretical IncursionDocument5 paginiMetatheatre: A Theoretical IncursionNicoleta MagalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Aristotelian Perspective in Otakar Zich's The Aesthetics of Dramatic Art PDFDocument14 paginiThe Aristotelian Perspective in Otakar Zich's The Aesthetics of Dramatic Art PDF蔡岳泰Încă nu există evaluări

- Woolf Impressionist TechnicqueDocument2 paginiWoolf Impressionist TechnicqueVanessa RidolfiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SHKLOVSKY, Viktor - The Resurrection of The WordDocument4 paginiSHKLOVSKY, Viktor - The Resurrection of The WordOmega Zero100% (4)

- Aristotle's Theory of Poetic ImitationDocument10 paginiAristotle's Theory of Poetic ImitationAngel AemxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetics PDFDocument93 paginiPoetics PDFCristina IonescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epic Notes PoeticsDocument20 paginiEpic Notes Poeticssamita ranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reader. Contemporary Critical TheoriesDocument226 paginiReader. Contemporary Critical TheoriesAnca Silviana100% (2)

- The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Volume 44 Issue 1 1985Document19 paginiThe Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Volume 44 Issue 1 1985Janaína NagataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristotle - PoeticsDocument34 paginiAristotle - PoeticsMuzaffer Derya Nazlıpınar100% (1)

- AristotleDocument2 paginiAristotleM Asad HAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resumen Viktor ShklovskyDocument3 paginiResumen Viktor ShklovskyOrlando Rafael Vivas OropezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristotle MimicsDocument2 paginiAristotle MimicsJoydev DemodakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ranciere - Is There A Deleuzian AestheticsDocument14 paginiRanciere - Is There A Deleuzian AestheticsDennis Schep100% (1)

- The Fallacies in Literary CriticismDocument3 paginiThe Fallacies in Literary CriticismPsyche MamarilÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Essay On Stage: Singularity and PerformativityDocument15 paginiThe Essay On Stage: Singularity and PerformativitySlovensko Mladinsko Gledališče ProfilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formalism: Clive Bell and Viktor Shklovsky: Trevor PatemanDocument4 paginiFormalism: Clive Bell and Viktor Shklovsky: Trevor PatemanÖzenay ŞerefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mary Ellen Solt Concrete Poetry A World ViewDocument91 paginiMary Ellen Solt Concrete Poetry A World Viewzezi bon100% (2)

- Course AshberyDocument4 paginiCourse AshberyMia ElaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deframing Theory & Poetry Re Formatted 1Document16 paginiDeframing Theory & Poetry Re Formatted 1Yasser K. R. AmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wordsworth-Preface To The Lyrical BalladsDocument19 paginiWordsworth-Preface To The Lyrical BalladsIan BlankÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unities Presented by AristotleDocument4 paginiUnities Presented by AristotleShani ManiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MimeticDocument4 paginiMimeticImee Joy DayaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Historical Survey of Literary CriticismDocument4 paginiA Historical Survey of Literary CriticismKring RosseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coleridge As CriticDocument8 paginiColeridge As CriticshahzadÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Vortex That Unites Us: Versions of Totality in Russian LiteratureDe la EverandThe Vortex That Unites Us: Versions of Totality in Russian LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4433 Shelley DefenceDocument4 pagini4433 Shelley DefenceVera StankovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prirodne Nauke 120Document356 paginiPrirodne Nauke 120Vera StankovÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- The Riddle of Bacchae PDFDocument244 paginiThe Riddle of Bacchae PDFVera Stankov100% (2)

- Gauss PDFDocument37 paginiGauss PDFIlduceGaribaldiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grčka SkulpturaDocument22 paginiGrčka SkulpturaVera StankovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Page 65 - 74 Indian HistoryDocument10 paginiPage 65 - 74 Indian HistoryCgpscAspirantÎncă nu există evaluări

- Past Simple Vs ContinuoDocument3 paginiPast Simple Vs Continuoj.t.LLÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cinderella Story As Example of Narrative TextDocument2 paginiCinderella Story As Example of Narrative TextHikmatul Maghfiroh100% (1)

- Assign2 - BS Archi 1 4Document8 paginiAssign2 - BS Archi 1 4Lady Claire LeronaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Glories of Offering A Lamp During The Month of KartikaDocument2 paginiGlories of Offering A Lamp During The Month of KartikaRohit Karan GobooriÎncă nu există evaluări

- EPIC of IBALONGDocument4 paginiEPIC of IBALONGVal TarrozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingDocument7 paginiA Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingbadhabitÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6min English Family HistoryDocument5 pagini6min English Family HistoryJavier AmateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Litvin On HamletDocument20 paginiLitvin On HamlettranslatumÎncă nu există evaluări

- GRT 1 - Seating ArrangementDocument11 paginiGRT 1 - Seating ArrangementAmiya Kumar DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Filipino Spirit Through TimeDocument8 paginiThe Filipino Spirit Through TimeJesselle ArticuloÎncă nu există evaluări

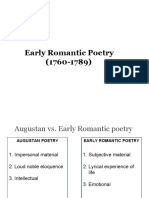

- 3 - Early Romantic PoetryDocument22 pagini3 - Early Romantic PoetryDestroyer 99Încă nu există evaluări

- Tarikh e Masoodi (Mas'Udi) Tarjuma Muruj Al Zahab Wa Madin Al Jawahir Al Masoodi Jild-2 @Document429 paginiTarikh e Masoodi (Mas'Udi) Tarjuma Muruj Al Zahab Wa Madin Al Jawahir Al Masoodi Jild-2 @Faryal Yahya MemonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1Document7 paginiUnit 1Adilah SaridihÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Bavarian Illuminati: New World OrderDocument2 paginiThe Bavarian Illuminati: New World OrderSkotty1111Încă nu există evaluări

- Mantra Push PamDocument2 paginiMantra Push PamnsiyamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Test 1Document6 paginiPractice Test 1dyan missionaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sanctuary Doctrine - A Critical-Apologetic Approach, Florin Laiu, 2011Document85 paginiThe Sanctuary Doctrine - A Critical-Apologetic Approach, Florin Laiu, 2011miklos palfi100% (2)

- Poets of Medieval EraDocument4 paginiPoets of Medieval EraLaiba ShabbirÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 HBET4303 Course GuideDocument6 pagini04 HBET4303 Course GuidezakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- شرح للمطلحات الشعرية وامثلةDocument24 paginiشرح للمطلحات الشعرية وامثلةOsamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DICTION: Word ChoiceDocument7 paginiDICTION: Word Choiceapi-234467265Încă nu există evaluări

- German ContextDocument3 paginiGerman ContextStjanu DebonoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddhist Civilization in TibetDocument96 paginiBuddhist Civilization in TibetLalitaJangra50% (2)

- Introduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderableDocument17 paginiIntroduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderablePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Encyclopedia EvaluationDocument29 paginiEncyclopedia EvaluationIbrahimh504Încă nu există evaluări

- NeoclassicismDocument22 paginiNeoclassicismMiguel CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- IhsanDocument3 paginiIhsanMd. Naim KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- LitCharts Daybreak in AlabamaDocument10 paginiLitCharts Daybreak in AlabamahltmtomliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irony 2Document3 paginiIrony 2api-242269312Încă nu există evaluări