Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

20 Midi Tips

Încărcat de

sheol67198Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

20 Midi Tips

Încărcat de

sheol67198Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

intermusic.

com

Page 1 of 3

20 MIDI Tips

Keep your MIDI system in shape with these tips...

MIDI is one of the fundamental parts of making music in a studio, and yet it also seems to be the most common

stumbling block. Instrument Digital Interface was originally developed by the Roland Corporation, and appeared

on the market way back in 1983 as a way of syncing together different makes and models of musical equipment.

By 1985 just about every manufacturer's synth gear featured this new system. Despite the innovation, people

have always loved it or hated it, but regardless of anyone's feelings, MIDI is something everyone will be forced to

deal with sooner or later.

Rather than spend a long afternoon attacking your MIDI cables with a pair of pliers and a soldering iron in the

hope of playing some of your MIDI files through your hi-fi, take a break from your music to digest a few of these

basic MIDI principals. Then see if you can apply to your music some of the concepts and nifty tricks MIDI has to

offer.

MIDI basics

MIDI In. All your MIDI data enters at the MIDI In port. An example would be on your synth or sampler where it

receives information from your sequencer. MIDI Out. All the MIDI data generated from each device is sent from

the MIDI Out port. This could be at your sequencer where it distributes material to your synths, or on your synth

for playing notes of other gear. Sometimes the Out port can be configured to function as a Thru port by changing

a setting in a menu of your synth.

MIDI Thru. The MIDI Thru port retransmits any data received at the MIDI In port. It is commonly used to link

multiple devices together on a single MIDI path in a daisychain fashion. The term MIDI Thru is also often used on

computer sequencers as a way of allowing MIDI data from your master keyboard to pass through your sequencer

and on to your other synths via the MIDI Out on your computer's MIDI interface.

Cable lengths. Keep the length of your MIDI cables to an absolute minimum. It is crucial that an accurate signal

arrives at your synth or sampler. Large cable runs create resistance which may corrupt the data, causing missed

notes or erratic behaviour.

Flower power. Daisychaining refers to linking pieces of equipment together on a single MIDI path by using the

Thru port on one device to transfer the MIDI data on to the In port of the next. By limiting the amount of devices

connected in this fashion to a maximum of three, you reduce the chance of MIDI data becoming corrupted along

the way. Any additional devices should be connected to another Out port on your MIDI Interface.

The bumpy MIDI road

MIDI loopy. MIDI loops occur when MIDI data circles back and arrives at the same place. This causes each

sound to attempt to play twice, sometimes causing a flanged sound. It is particularly noticeable on percussion

sounds and monophonic synth patches. When working with a sequencer, ensure that your master controller synth

is set to Local Off, or alternatively, turn off the MIDI Thru option in the sequencer so the synth's sound engine

doesn't receive messages directly from the keyboard, as well as returning back from the sequencer.

MIDI congestion. All messages travel along the MIDI cable, one after the other, in a serial fashion. Often you'll

have several notes playing at exactly the same time in your sequencer, but this can cause cause irregular timing

errors during playback with certain notes sounding late due to them waiting for their instructions. You can keep

things sounding tight by keeping the percussion and rhythmic sounds exactly where they are, then slightly shift

any other sounds forwards or backwards in your sequencer to allow the crucial data time to get to where it has to

go, on time.

Out and Out again. Each MIDI line can carry up to 16 channels, or parts. To send additional parts you will require

additional ports, with some MIDI interfaces offering up to eight ports (that's 128 channels!). If you're using several

http://www.intermusic.co.uk/print.asp?ReviewId=2593&ArticleTable=Features&Feature...

25/06/2001

intermusic.com

Page 2 of 3

devices daisychained together, try to run each device off its own MIDI interface Out port. This helps improve MIDI

timing by sending each device's set of messages on its own cable, at the same time. Far more efficient than

sending everything, one by one, through a single cable.

Going solo. When recording individual instrument parts, always solo the MIDI track in your sequencer to

minimise timing inconsistencies during MIDI sequence playback. Otherwise the MIDI cable becomes busy with the

traffic for all the other parts.

The naming game. To save yourself the time and hassle of manually typing all the patch names of your gear into

your sequencer, try downloading the manual PDF file from the manufacturer's Web site. You can then freely copy

and paste the names from the manual's instrument list. Make sure you've got something like Acrobat Reader to

read the PDFs of course.

Clock this! For editing purposes, it is handy to learn what each note value is worth in relation to the MIDI clock. If

the MIDI clock resolution is 96 ticks per quarter note, then simple mathematics will work out the the other note

values:

384 = 1 bar/measure

192 = 1/2 bar/measure

96 = 1/4th note

48 = 1/8th note

24 = 1/16th note

12 = 1/32nd note

6 = 1/64th note

If resolution is 960, then multiply each value by 10.

MIDI effects processor

Note: Because MIDI consists of instructions that tell a device what to do, and not actual audio waveforms, you

can't insert your favourite distortion effect into the MIDI path and get the desired effect. As synths become more

multi-timbral, you are often left with a limited array of onboard effects to treat all those parts. Here are a few MIDI

tricks to emulate some of the more traditional audio effects to free up your effects unit for more important duties.

Delay today. Some sequencers have a special option to recreate delay automatically by using MIDI notes. Note

that delays created through MIDI may use up polyphony to create the additional notes, and therefore won't work

with overlapping monophonic patches. You can do this on any sequencer by copying the series of notes to be

delayed on to several new MIDI tracks.

To create the speed of the delay, shift the group of notes of each new track to some point later than the original.

You can creatively lock the repeated notes in time with the BPM by using specific note values to shift the delayed

tracks. To set the feedback, reduce the velocity of each progressively delayed track.

Playing ping pong. After creating the delay from tip 12, insert MIDI pan commands prior to each note to achieve

that ping pong effect where each subsequent delayed note alternates between the left and the right.

Close the gate! A noisegate normally allows audio to pass through, but cuts off once the audio drops past a

certain volume. It can also be triggered to open and close by an external source. To create this effect with MIDI,

use MIDI Volume messages inserted in regular intervals to open and shut the gate. Have the volume open and

close on every eighth or 16th note for a stuttering trance effect. This works particularly well on synth pads and

vocals. Smooth out the effect with a little added reverb.

Metamorphosis. Sound morphing is a feature found on a lot of modern synths that allows one sound to evolve

slowly into another. To achieve this on any multitimbral synth, duplicate a sequencer track so it plays an identical

sequence to two different sounds (on different channels). Use MIDI Volume CC messages to keep one sound

silent. Then at a point along the sequence, ramp up the volume of this sound whilst bringing down the volume of

the other to create the morph effect. A good example would be a clean string pad which evolves into a raw and

gritty resonant pad.

Fade away. With the nature of today's electronic music often consisting of a

collection of copy and pasted MIDI or audio

sections, this often results in new sounds and sequences entering and exiting from the track quite abruptly.

Implement plenty of MIDI CC volume fades into and out of some of your sequenced sections to maintain a smooth

overall flow, with the effect of a DJ blending two records via a mixer's crossfader.

Cymbal symbolism. Often percussion hits are assigned to different groups (in your synth) with rules set up to

http://www.intermusic.co.uk/print.asp?ReviewId=2593&ArticleTable=Features&Feature...

25/06/2001

intermusic.com

Page 3 of 3

ensure that hits within the same group can not sound together. You can use this to your advantage to act like a

choke to tidy up a sloppy open hat or crash cymbal. Enter a low velocity MIDI note of the same group during the

decay to cut off the cymbal sound at a specific point.

Gimme space! Duplicate a MIDI track in your sequencer to play an identical patch on two channels in your synth.

Pan one channel left and the other right. Now shift one of the MIDI tracks so it plays late by a couple of clicks to

separate the stereo image. You can even try substituting one of the patches for something similar for a true stereo

sound. Adjust the pan controls towards the centre to reduce the stereo separation, leaving a fattened sound.

Effects effective. If you're shopping for an effects unit, consider one with MIDI. Apart from being able to switch

between presets, you can also set up your sequencer to automatically control a whole series of other parameters,

such as gradually raising the feedback of a delay, increasing the depth of a phaser, or boosting the drive of the

distortion.

More multi. Many synths allow each patch to be made up of several layers. By assigning each layer to respond

from different sections of the keyboard, you can build up patches that contain several individual instrument

sounds. If your synth allows four layers per patch, then you can effectively transform your measly module's 16

parts into a 64-part multitimbral mighty MIDI module monster!

Phil Booth 10/00

http://www.intermusic.co.uk/print.asp?ReviewId=2593&ArticleTable=Features&Feature...

25/06/2001

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Ultimate Guide to Music Production and Sound EngineeringDe la EverandThe Ultimate Guide to Music Production and Sound EngineeringÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Signal Processing for Audio Applications: Volume 2 - CodeDe la EverandDigital Signal Processing for Audio Applications: Volume 2 - CodeEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- The Fundamentals of Synthesizer ProgrammingDe la EverandThe Fundamentals of Synthesizer ProgrammingEvaluare: 1.5 din 5 stele1.5/5 (2)

- MIDI Short For Musical Instrument Digital Interface) Is A TechnicalDocument10 paginiMIDI Short For Musical Instrument Digital Interface) Is A TechnicalJomark CalicaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midi Guide Manual RolandDocument27 paginiMidi Guide Manual RolandJoeriDD100% (1)

- Paul White MiDi BasicsDocument10 paginiPaul White MiDi BasicsCarlos I. P. GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthesizer Cookbook: How to Use Filters: Sound Design for Beginners, #2De la EverandSynthesizer Cookbook: How to Use Filters: Sound Design for Beginners, #2Evaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (3)

- The Power in Logic Pro: Songwriting, Composing, Remixing and Making BeatsDe la EverandThe Power in Logic Pro: Songwriting, Composing, Remixing and Making BeatsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Pro Techniques For Home Recording: Studio Tracking, Mixing, & Mastering Tips, Tricks, & Techniques With AudioDe la EverandPro Techniques For Home Recording: Studio Tracking, Mixing, & Mastering Tips, Tricks, & Techniques With AudioEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

- Pro Tools For Breakfast: Get Started Guide For The Most Used Software In Recording Studios: Stefano Tumiati, #2De la EverandPro Tools For Breakfast: Get Started Guide For The Most Used Software In Recording Studios: Stefano Tumiati, #2Încă nu există evaluări

- Power Tools for Studio One 2: Master PreSonus' Complete Music Creation and Production SoftwareDe la EverandPower Tools for Studio One 2: Master PreSonus' Complete Music Creation and Production SoftwareÎncă nu există evaluări

- MIDI 101 by TweakHeadz LabDocument9 paginiMIDI 101 by TweakHeadz LabBrandy ThomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Beginner's Guide To MidiDocument11 paginiThe Beginner's Guide To MidiAnda100% (6)

- The Beginners Guide To MidiDocument10 paginiThe Beginners Guide To MidiNedFlaherty100% (2)

- Midi PowerDocument17 paginiMidi Powerteletext45100% (3)

- The Professional Songwriting Guide: 10,000 Songs Later... How to Write Songs Like a Professional, #3De la EverandThe Professional Songwriting Guide: 10,000 Songs Later... How to Write Songs Like a Professional, #3Încă nu există evaluări

- Music Creation: A Complete Guide To Producing Incredible SongsDe la EverandMusic Creation: A Complete Guide To Producing Incredible SongsÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA The Book Vol 2: The Recording Architecture Book of Studio DesignDe la EverandRA The Book Vol 2: The Recording Architecture Book of Studio DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- Making the Scene: Nashville: How to Live, Network and Succeed in Music CityDe la EverandMaking the Scene: Nashville: How to Live, Network and Succeed in Music CityEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- My Passion “Audio Awareness”: It’S All About “Audio Recording” & “Live Sound” ExperienceDe la EverandMy Passion “Audio Awareness”: It’S All About “Audio Recording” & “Live Sound” ExperienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Story of Paul Bigsby: The Father of the Modern Electric Solid Body GuitarDe la EverandThe Story of Paul Bigsby: The Father of the Modern Electric Solid Body GuitarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philip “Flip” Gordon: Jazz Compositions Volume 2: Zodiac Project: Secrets D’HistoireDe la EverandPhilip “Flip” Gordon: Jazz Compositions Volume 2: Zodiac Project: Secrets D’HistoireÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ultimate Midi Guide From PDFDocument4 paginiUltimate Midi Guide From PDFnetzah2padre100% (1)

- A Guide To MIDIDocument24 paginiA Guide To MIDIDaisy Grace Wakefield0% (1)

- The 5 Keys to a Clear Mix: Create YOUR Mix Philosophy for Christian Artists, Songwriters, and Church Sound MixersDe la EverandThe 5 Keys to a Clear Mix: Create YOUR Mix Philosophy for Christian Artists, Songwriters, and Church Sound MixersÎncă nu există evaluări

- LMMS: A Complete Guide to Dance Music ProductionDe la EverandLMMS: A Complete Guide to Dance Music ProductionEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (2)

- How to compose songs in 30 minutes using your iPhone or iPadDe la EverandHow to compose songs in 30 minutes using your iPhone or iPadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ableton Live 101: An Introduction to Ableton Live 10De la EverandAbleton Live 101: An Introduction to Ableton Live 10Evaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (6)

- RA The Book Vol 3: The Recording Architecture Book of Studio DesignDe la EverandRA The Book Vol 3: The Recording Architecture Book of Studio DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Double Bass Player: From child prodigy to serial murderDe la EverandThe Double Bass Player: From child prodigy to serial murderÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Performance Loudspeakers: Optimising High Fidelity Loudspeaker SystemsDe la EverandHigh Performance Loudspeakers: Optimising High Fidelity Loudspeaker SystemsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Songbook "Melody Star" Harmonica - 40 Classical Music Themes: Melody Star Songbooks, #9De la EverandSongbook "Melody Star" Harmonica - 40 Classical Music Themes: Melody Star Songbooks, #9Încă nu există evaluări

- Process Orchestration A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDe la EverandProcess Orchestration A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Composing Adventure: Conversations with Composers about Great Adventure ScoresDe la EverandComposing Adventure: Conversations with Composers about Great Adventure ScoresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthesizer Explained: The Essential Basics of Synthesis You Must Know as a Digital Music Producer (Electronic Music and Sound Design for Beginners: Oscillators, Filters, Envelopes & LFOs)De la EverandSynthesizer Explained: The Essential Basics of Synthesis You Must Know as a Digital Music Producer (Electronic Music and Sound Design for Beginners: Oscillators, Filters, Envelopes & LFOs)Evaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (3)

- Welcome to the Jungle: A Success Manual for Music and Audio FreelancersDe la EverandWelcome to the Jungle: A Success Manual for Music and Audio FreelancersÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Legend VST Factory Default PatchesDocument480 paginiThe Legend VST Factory Default PatchesPumping Alien100% (11)

- Harmonic Odyssey - 25 Neo Soul Chord Progressions UnveiledDe la EverandHarmonic Odyssey - 25 Neo Soul Chord Progressions UnveiledÎncă nu există evaluări

- BOTA CoursesDocument1 paginăBOTA Coursessheol6719867% (12)

- The War of ArtDocument1 paginăThe War of Artsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Why Is It That If You Tickle Yourself It Doesn't TickleDocument1 paginăWhy Is It That If You Tickle Yourself It Doesn't Ticklesheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- 01.03 Expected Value PDFDocument6 pagini01.03 Expected Value PDFAnna BarthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chi Power Plus PDFDocument35 paginiChi Power Plus PDFmrushdan13575% (4)

- Eminent DomainDocument2 paginiEminent Domainsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Paper - How To Write Journal PaperDocument17 paginiPaper - How To Write Journal PaperAmit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- May Bethel - The Healing Power of HerbsDocument104 paginiMay Bethel - The Healing Power of Herbssheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Techno Tips PDFDocument2 paginiTechno Tips PDFsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Paper - How To Write Journal PaperDocument17 paginiPaper - How To Write Journal PaperAmit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motown SoundDocument4 paginiMotown Soundsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Guide To MIDI (PT I) : A Brief History and Explanation of The Mystery of MIDI..Document3 paginiGuide To MIDI (PT I) : A Brief History and Explanation of The Mystery of MIDI..RagagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pickup Tricks 1Document2 paginiPickup Tricks 1sheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Reference MonitorsDocument9 paginiReference MonitorsAndrew MaverickÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robo VoxDocument3 paginiRobo Voxsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Impedance 101 - Part 1Document5 paginiImpedance 101 - Part 1sheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Pickup Tricks 2Document2 paginiPickup Tricks 2sheol67198100% (1)

- EQ Masterclass From PDFDocument6 paginiEQ Masterclass From PDFChasity Snyder100% (1)

- Guide To Gating PDFDocument3 paginiGuide To Gating PDFsteve5437Încă nu există evaluări

- Guitars and SamplingDocument2 paginiGuitars and Samplingsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Digital Mixing: Page 1 of 3Document3 paginiDigital Mixing: Page 1 of 3sheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Digital RecordingDocument2 paginiDigital Recordinggeobv77Încă nu există evaluări

- Shaman Training ExercisesDocument7 paginiShaman Training Exercisessheol67198100% (3)

- DIY Rare GroovesDocument3 paginiDIY Rare Groovessheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Cubase VST PC Power Tips PDFDocument2 paginiCubase VST PC Power Tips PDFsheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Your Analogue MixerDocument3 paginiYour Analogue Mixersheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- CubaseMasterClass 2Document4 paginiCubaseMasterClass 2sheol67198Încă nu există evaluări

- Self Defence RecommendationsDocument13 paginiSelf Defence RecommendationsGEOMILIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moog MF 105m Murf NoticeDocument14 paginiMoog MF 105m Murf NoticeOsmatranja KraljevoÎncă nu există evaluări

- WK6 8se UkDocument310 paginiWK6 8se Ukgg_dudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operating System 3.01Document48 paginiOperating System 3.01László MagyarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Escription of Ontrols: Front PanelDocument18 paginiEscription of Ontrols: Front Panelk6mayÎncă nu există evaluări

- M32-Edit V 3.2 PDFDocument2 paginiM32-Edit V 3.2 PDFDodi HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

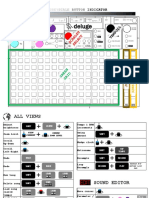

- Deluge Cheat SheetDocument7 paginiDeluge Cheat Sheetjeremy_grxÎncă nu există evaluări

- AVmixer Pro 2 User Manual MAC-V2Document18 paginiAVmixer Pro 2 User Manual MAC-V2vieloveÎncă nu există evaluări

- RRLDocument223 paginiRRLFritz Andre PrimacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- LPC-Live 2 User ManualDocument21 paginiLPC-Live 2 User ManuallasseeinarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tanzbar Manual EnglishDocument17 paginiTanzbar Manual EnglishVangelisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ivory Standalone (PC) User GuideDocument5 paginiIvory Standalone (PC) User GuideToshiro NakagauaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Audity 2.0 UpdatesDocument22 paginiAudity 2.0 UpdatesRudy PizzutiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flkey 49 61 User Guide-PDF-EnDocument47 paginiFlkey 49 61 User Guide-PDF-Encain919Încă nu există evaluări

- GlovePIE GuideDocument127 paginiGlovePIE Guide금민제Încă nu există evaluări

- 1990's - Today Write UpDocument7 pagini1990's - Today Write UpCallumÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAE BeogradDocument12 paginiSAE BeogradPoprilično NikolicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fantom-G Micro ManualDocument32 paginiFantom-G Micro ManualPete MillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manuale Motherboard QDI Advance 10TDocument74 paginiManuale Motherboard QDI Advance 10Tjesus ortunoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Performer Getting StartedDocument198 paginiDigital Performer Getting Startedtelengard_tÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Bucket Brigade DelayDocument6 paginiFull Bucket Brigade DelayCarmelo EscribanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traktor 2 - Application ReferenceDocument308 paginiTraktor 2 - Application ReferenceThomas GrantÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rd2000 Rear Panel DescriptionDocument4 paginiRd2000 Rear Panel DescriptiongwillimwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synthstrom Audible Deluge Manual PDFDocument94 paginiSynthstrom Audible Deluge Manual PDFCristobalzqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Casio CDP-100 Service Manual PDFDocument23 paginiCasio CDP-100 Service Manual PDFMao527kingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electric Piano: User GuideDocument22 paginiElectric Piano: User GuidedabdabdabdabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Korg Minilogue ManualDocument58 paginiKorg Minilogue ManualadomarcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Maker: PremiumDocument298 paginiMusic Maker: PremiumAwal BrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- G66.eu - Axe-Fx IIIDocument38 paginiG66.eu - Axe-Fx IIIPetr PetrovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Help Troubleshooting MIDI Receive Circuit. - Audio - Arduino Forum OptoacopladorDocument6 paginiHelp Troubleshooting MIDI Receive Circuit. - Audio - Arduino Forum OptoacopladorsegurahÎncă nu există evaluări

- What's New in Pro Tools 2020.9 PDFDocument12 paginiWhat's New in Pro Tools 2020.9 PDFRaffaele CardoneÎncă nu există evaluări