Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Risk Management For Sovereign Debt

Încărcat de

Rodrigo CostaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Risk Management For Sovereign Debt

Încărcat de

Rodrigo CostaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

Part 1 Risk Management

Chapter 1

Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-1

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1-2

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

Part 1 Risk Management

Chapter 1

Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1.1

Introduction ......................................................................................................1-5

1.2

Setting the Goal and Establishing Constraints ...................................................1-5

1.3

Classes of Risk ..................................................................................................1-7

1.4

Risk As a Macroeconomic Problem .....................................................................1-9

1.5

Risk Management of Contingent Obligations ....................................................1-10

1.6

Risk Tolerance and Performance Measurement ................................................1-15

1.7

Procedures for Managing Market Risks and Returns ........................................1-19

1.8

A Structured Approach to Organization and Information Architecture..............1-20

1.9

Organization Structure

1.10

Information Architecture Using Separate but Integrated Databases ................ 1-28

................................................................................1-22

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-3

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1-4

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

Part 1 Risk Management

Chapter 1

Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1.1

Introduction

This document provides a framework to help

sovereign debt managers meet their goal

sustained ability to fund scal needs while

remaining within funding policy objectives and

risk targets. This is the context for assessing

whether the compensation for risk exposure is

adequate. This is an optimizing framework.

This framework helps promote efcient

management of the sovereigns debt. Given the

constraints and risk limits, are borrowing costs

as low as feasible and is risk exposure rewarded

appropriately in light of market conditions? But

the relevant concept for the sovereign is not

simply being compensated for risk exposure.

It is far beyond that because sovereign debt

has important macro-economic impact. At one

extreme, an inappropriate exposure structure

in debt and sovereign guarantees has caused

some countries economic downturns to become

crises, whereas a well-implemented optimized

debt and guarantees structure can actually

help promote cyclical stability. Moreover, a well

designed debt structure can help the sovereign

promote its own local currency capital market,

with associated benets for home ownership

and business nancing, and it can help provide

instruments for effective monetary policy

transmission.

This chapter describes the thinking process that

underpins an optimizing approach to sovereign

debt management. It describes the important

rst step, setting the goal and establishing

the limits. It then describes the types of

risks. Effective risk management is one of the

important tests of a borrowers credit rating,

which ultimately inuences the borrowers

availability and cost of funds relative to other

borrowers.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Two of the principal risks facing all debt

portfolio managers are market risk and

operational risk. Market risk can be measured,

which requires a coherent data structure

and tools for measuring and managing risk.

Operational risk arises largely from a weak

organizational structure. Operational risk

can be managed through an organizational

structure that provides for appropriate

separation of responsibilities and uses welldened procedures for accurate and timely

accounting.

This chapter discusses the various types of

risk and how they can be managed. It then

introduces an approach to assessing and

reviewing the structure of the organization and

its information requirements. It proposes an

information management system that suits

each of the two main functions for managing

debt accounting/budgeting and policy/risk

managementin a separate but integrated way.

This chapter also introduces stress testing for

risk measurement and management. Both of

these are discussed in more detail in technical

chapters that follow this one.

1.2

Setting the Goal and Establishing

Constraints

Sovereign debt is an explicit contractual

obligation of the sovereign to repay, usually

with interest and at a specied time, funds

that have been provided to it. The obligation

ultimately takes the form of a contract to

borrow. In one case, the obligation might be

direct, meaning that there are only two parties

involved: the sovereign (as borrower) and the

provider of funds (the lender), and the full

faith and credit of the sovereign supports the

agreed repayment terms. In another case, the

1-5

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

obligation might be indirect, meaning that a

third party, such as an agency of the sovereign,

might be the nominal borrower and there might

not be a contractual underpinning of the full

faith and credit of the sovereign. A third is that

the obligation might be contingent, meaning

that a third party is the borrower with the

direct obligation to repay, and the sovereigns

obligation to repay contractually arises only

upon some event such as the failure of the

direct borrower to repay. A guarantee is a

contingent obligation.

In any case, the obligation to repay might be in

the sovereigns domestic currency (domestic

currency debt) or it might be in one or more

external currencies (foreign currency debt).

Foreign currency debt may have all the risks

and rewards of domestic currency debt.

Moreover, it has an additional risk/reward

component: there is the potential of either an

adverse or a benecial change in the foreign

exchange rate relative to what was accepted

when the exposure was agreed, resulting in

debt servicing being either more onerous or less

costly than anticipated.

We can think of sovereign debt management

as having two different dimensions that must

be considered. One dimension has all the

aspects of any portfolio management problem.

Where those pertain, the best approach for

asset-liability management as practiced in any

nancial institution can be used. There is one

small technical modication, however, in that

the appropriate measure for a sovereign is the

cash ows the sources of funds to service

the debt and the amount of funds needed to

service the debt. The second dimension is the

macro-economic implications of sovereign debt

management. Both are discussed below.

1.2.1 Risk as an Asset-Liability

Management Problem: From a

Cash Flow Viewpoint

Sovereign debt management shares some

features common to all asset-liability and

portfolio management for nancial institutions.

However, one signicant difference between

sovereign and corporate debt is that sovereign

debt management is viewed in terms of cash

ows. But this does not detract from the

1-6

Part 1 Risk Management

usefulness of the asset-liability management

approach. The features of that approach

applicable to sovereign debt management

include the need for a clear strategic objective

as well as establishment of constraints and

risk tolerances. They also include a need

for data and procedures to measure debt

portfolio market risk and returns; to manage

debt portfolio market risk and performance;

to manage the legal and other risks of issuing

debt; and to limit debt portfolio operational

risk. Viewed this way, there is a vast literature

and array of best practices and regulatory

standards available to serve as guidelines.

1.2.1.1

The Strategic Objective and the

Setting of Constraints and Risk

Tolerances

Any asset-liability management structure

should be framed in terms of the organizations

objective and mission. This frame ultimately

establishes the goal for portfolio management,

and in the process helps dene the strengths

and weaknesses of the entity. The constraints

similarly provide the boundaries for the portfolio

managers, as do the risk tolerances. Portfolio

management ultimately is an optimization

problem, even though that explicit term is

rarely used. The approach to getting clarity on

the objective, constraints, and risk tolerances

involves achieving consensus, or at least

working agreement, among the stakeholders.

This consensus among stakeholders is

particularly important in managing public

debt. Achieving that clarity of objective and

consensus also requires expertise and technical

sophistication to be able to evaluate and

measure potential risks and returns, as well

as the likely consequences of risk exposures

entailing possibly large losses. Skills also are

needed to communicate these results to nontechnical stakeholders in order to establish

meaningful risk tolerances. A framework of

the strategic objective, constraints and risk

tolerances allows the portfolio managers to

have a real basis for evaluating choices among

instruments or markets, and it provides

their superiors and the public the basis for

meaningful evaluation of performance.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1.3

Classes of Risk

The classic denition of risk refers to exposure

to an event that has some chance of occurring,

causing a gain or a loss. The chance of its

occurrence can be measured reasonably

accurately.1 Uncertainty, in contrast, is the

term used for an occurrence that can result in

unusual gain or loss, but whose probability of

occurrence cannot be measured reliably.

Measurement of risk is a key feature of risk

management as applied to nancial portfolios

and nancial intermediaries. A reliable range

of the probability of gain or loss is an essential

ingredient of successful risk taking and risk

management. That information also permits a

reliable estimate of risk bearing capacity. Such

estimates serve as useful decision tools for

evaluating pricing and risk-adjusted returns on

capital.

Many kinds of nancial risk lend themselves to

measurement and therefore to this quantitative

approach to risk management. Market risk is a

prime example. It includes a range of interest

rate risks yield curve risk, yield levels risk,

basis risk. It also includes uctuations in

the value of currencies against each other,

liquidity risk and market price risk. Funding

risk is another measurable nancial risk.

Some types of credit risk also can be managed

using quantitative techniques if the number

of observations and data records allow. For

example, in the U.S., many types of consumer

loans for home mortgages, cars and credit

cards, for example lend themselves to

quantitative approaches.

Since market risk can be measured and

managed, it is suited to intelligent, focused,

potentially protable risk taking. This

undertaking is supported by estimates

of both an adequate capital base and an

adequate risk-adjusted return on capital.

This is the foundation for successful nancial

intermediation and portfolio management.

Other kinds of risk can involve losses severe

enough even to cause failure but they do not

lend themselves to a quantitative approach

1

Part 1 Risk Management

to measurement or management. They are

classes of risks that are best managed through

control procedures, and are referred to as

operational risk. Controls and reputation

risks are prime examples. They might arise,

for example, through conict of interest or

from rogue behavior not properly managed or

controlled. They might reect moral hazard,

where something in the reward or performance

structure encourages risk taking without

commensurate risk consequences. Examples

often emerge in the transactions areas, where

they might be as simple as mistakes that go

undetected until too late or other, self-serving,

mistakes that allow an improperly supervised

employee to reap undeserved gains. Operational

risks almost never result in gains to the

organization. They are usually associated with

losses, losses that range from the trivial to the

fatal. As such, they do not lend themselves to

the calculated risk-taking associated with most

market risks, where rewards can be correlated

with risk and where good portfolio management

through techniques such as diversication

and notional risk-capital allocation can

mitigate exposure. Most institutions view

operational risk as a risk to be avoided or at

least minimized. They tend to do this through

organizational structures designed to make the

control mechanisms as effective as possible.

Finally, there is a class of risks termed country

riskrisk that is systemic and beyond the

immediate purview of the manager of the

portfolio or nancial intermediary. These

represent changes in the external environment

that can affect the success of the portfolio.

Unexpectedly high or volatile ination is

one example. Another example might be a

deterioration in a countrys own sovereign

debt rating, since that serves to underpin the

debt rating of any entity from that country

that also is issuing debt in external markets.

Regulatory risk can be systemic, since decisions

taken by regulators can affect the viability of

whole classes of portfolios or intermediaries.

The widespread failures of savings and loan

associations in the United States in the 1980s

were a very expensive example of regulatory risk.

Frank Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Prot, 1921 republished in Midway Reprint, Chicago:

The University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-7

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

In summary, market risk is best managed

quantitatively through reliance on data and on

the tools available to analyze data. Operational

risks are best managed by avoidance where

possible and otherwise by limiting techniques.

Appropriate organization structure tends to

be one of the most effective tools for avoiding

or limiting operational risks. Even though

country risks such as systemic and regulatory

risk might be seen as outside the control

of individual portfolio managers, individual

managers can nonetheless make a contribution

to the management of these macro risks. Their

contribution would be made by evaluating the

consequences of potential decisions through the

same good what if simulations as are used to

manage market risks and then communicating

their ndings to policymakers.

It is helpful to disaggregate the fundamental

risks into specic risks that permit

measurement and effective mitigation actions.

For sovereign debt management, the risks

discussed above take the following forms:

Funding risk - the risk that the ability

to fund new cash needs or to rollover

existing debt will be sharply curtailed as

to quantity, or quantity at terms that can

be accepted.

Market risk - risk that arises from

normal operations in the interest rate and

foreign exchange markets.

Credit risk - risk that partners in

business transactions will not pay as

promptly or as fully as anticipated when

the transaction was agreed.

Operational or controls risk - risk that

arises from administrative processes in

debt issuance, trading, accounting and

redemption operations.

Country risk - risk arising from the

overall nancial economic and political

condition of the country or from a major

failure of controls that damages the

countrys reputation.

Part 1 Risk Management

These broad categories of risks are

elaborated below.

Funding risk

Volume. The risk that the Ministry of

Finance will be unable to provide sufcient

funds to meet the governments expenditure

and debt reduction targets, on time.

Refunding. The risk that the Ministry of

Finance will be unable to rollover maturing

obligations.

Market risk

Currency. The risk that an adverse change

in the exchange rate would increase the

current debt servicing requirements of

a loan denominated in foreign currency

relative to the funds available to service that

debt.

Liquidity. The risk that securities cannot be

readily converted to cash for their full face

value, despite having short maturities and a

domestic currency denomination.

Marketability. The risk that securities cannot

be readily sold at a reasonable price, even

if not their full face value, either because

of discontinuities in the marketplace or

because the market for those particular

instruments is too thin.

Interest Rate. The risk that, relative to

the funds available to service debt, debt

service costs will increase directly or the

opportunity to reduce debt service costs

will be foregone as a result of adverse price

movements in nancial markets.

Instrument. The risk that an option

embedded in a complex security will

produce costs in excess of those anticipated

at the time the option was created.

Credit risk

Counter-party. The risk of nonperformance

by the obligor to a forward contract or

derivative.

Other Partner. The risk that a partner in a

contract other than that described above,

1-8

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

such as a borrower, will not pay the full

amount agreed in the contract in a

timely way.

Contingent. The risk that a contingent

obligation would be called, resulting in the

sovereign taking over the debt servicing

obligations of a guaranteed party. The

common cause for a contingent obligation to

be called is the guaranteed entity becoming

unable to service the debt.

Operational (controls) risk

Technical. The risk of inadequate internal

control in debt management operations,

which would allow embezzlement,

fraudulent transfer, or other loss to occur

undetected or with ease.

Settlement. The failure of a business partner

to settle on agreed terms, for reasons other

than the partners credit deterioration.

Country risk

Reputational. The risk that the credit

standing of the sovereign will deteriorate,

resulting in an increase in the interest cost

it would have to pay relative to that paid

by other borrowers. This event could be

associated with a lowered credit rating. At

the extreme, this refers to the risk that in

the wake of a default, an issuer will nd

market access severely curtailed or quite

expensive, or both.

Systemic. The risk arising from a widespread

failure, such as failure of the banking

system that leads to widespread collateral

failures. It might be caused by a failure of

the regulatory system or inadequate stoploss safety mechanisms, for example.

1.4

Risk As a Macroeconomic Problem

There are three principal additional

considerations for sovereign debt management

over and above standard asset-liability

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

management as practiced in a nancial

institution. The rst the nature of the sources

of funds available to service sovereign debt. The

second is the role of sovereign debt in country

crisis management. And an important third is

the role of sovereign debt issued in domestic

markets as a tool for open market monetary

policy operations and as a basis for developing

capital markets.

Sources of Funds Available to

Service Sovereign Debt

Debt risk management and optimization are

viewed in the context of the ow of funds

available to service the debt. Preserving or

improving the sovereigns highest feasible credit

standing important to achieving the main

goal for sovereign debt management can be

considered in cash ow terms. Credit standing

is strongest when there is a record of making

debt service payments in full and on time

and giving market participants condence

in the countrys continued capacity to do so.

In that regard, the currency composition of

funds ows available to service debt, and the

potential volatility associated with domestic

and external market conditions, are important

pieces of information, as are the size and

growth trend of these funds. Measuring sources

of funds available to service debt is typically

a coordinated effort. The sovereigns budget

and economics statistical functions would

be expected to make forecasts of funding

sources and provide them to the sovereign debt

management team. The central bank is often

the repository of information on quantities of

foreign currency available to make payments

on external debt, and would coordinate

this information with debt management.

Consequently, while important, the sources of

funds available to service debt are not discussed

further in this document as the focus is on

managing the requirements for servicing debt.

1-9

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

The Role of Sovereign Debt in

Country Crisis Management

Sovereign debt, including guarantees issued

by the sovereign, can play many roles in

country crisis management. Inappropriate debt

structures, such as those not well matched

to the cyclical patterns of funds available to

service debt, can in fact cause or exacerbate

crises. Exposure to contingent obligations

such as guarantees can create added stresses

on the sovereigns cash needs during a

crisis unless these potential calls have been

properly anticipated. Tests of the adequacy

of the margin by which funds sources of

the guaranteed entity exceed debt servicing

requirements provide an indication of the

probable calls on the sovereign. The capacity

to issue new debt as a source of liquidity to

weather a crisis is an important defense: one

goal of appropriate risk measurement and

management is to preserve that capacity. These

considerations need to be incorporated into the

overall goal and constraint setting of sovereign

debt management.

Sovereign Debt as a Policy

Instrument

The sovereign issues debt primarily for the

purpose of nancing a current or past decit.

The goal of debt management is to fund the

scal requirement. But debt management

also operates under a number of constraints

that arise from many aspects of sovereign debt

that inuence an economy. Agreement on

the nature and scope of these constraints is a

signicant part of the debt planning process.

Since government securities are also an

important vehicle for open market operations

conducted by central banks to implement

monetary policy, the central bank would

contribute to this process. Other interests and

agencies of government also are stakeholders in

the consensus building. For example, a desire

to develop a long-term home mortgage market

or longer-term corporate nance markets

also might be represented in establishing the

constraints for sovereign debt management.

The taxing and legislative authorities could have

important contributions to make in constraint

1-10

Part 1 Risk Management

setting and performance monitoring. The stage

of development of the capital market may be

a constraint. In the process of agreeing on

the goal and setting constraints, countries

should also bear in mind that sovereign debt

issuance and management can play a role in

fostering development of viable, transparent

domestic money and capital markets. Sovereign

debt provides a benchmark yield curve and

instruments for trading. It should also set a

standard for market operations.

During the early stages of a sovereign debt

market, market development is a principal

focus of the debt manager. A key rst step is

to reduce impediments to market development,

such as exposure to crises, liquidity strains,

and excessive volatility. One simple example

is managing the refunding portfolio to avoid

exceptionally large amounts of principal falling

due on a single day. Market development

consists of broadening the universe of investors,,

lengthening the yield curve, removing barriers

to development of the secondary market, and

deepening the primary market so as to permit

full nancing of the decit in the domestic

market in the year in which the decit occurs.

Once these conditions are met, the primary

focus of the debt manager can shift from

market development to risk management in the

debt portfolio. The goal at this point is further

reduction of risks to the state budget, beyond

those described as impediments to market

development.

1.5

Risk Management of Contingent

Obligations

Contingent obligations are a good example

of the intersection of nancial instruments,

nancial risk management, and the special

macroeconomic considerations unique to the

sovereign. In evaluating the benets and costs

of contingent obligations, the sovereign weighs

them not just in a static analysis but also in

terms of their dynamic or cyclical properties.

The sovereign assesses its contingent

obligations in the context of its responsibility to

manage the economy efciently, to avoid severe

cycles and crises, and to have in place effective

tools to manage such events if they do occur.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1.5.1 Sovereign Guarantees

A guarantee is a contract involving three

parties. The lender is one party to the

guarantee. The direct borrower, the guaranteed

party, is the second. And the guarantor is the

third. In this discussion, the guarantor is the

sovereign. The direct borrower is obliged to

repay the lender, as with any loan. However,

the guarantee provides that if certain specied

conditions arise, the guarantor is obliged

to repay the lender in place of the direct

borrower. The specied condition represents

the contingency of the obligation from the

guarantors viewpoint. Once the contingency

has occurred, the guarantors obligation to

repay is conceptually like any other form of debt

issued directly by the guarantor.

A common type of contingent obligation is a

credit substitution guarantee under which

a sovereign agrees to pay one or more of the

debt service payments owed by a third party

to a lender if that third party does not make

the payment on time and in full. This is a

simple substitution of the sovereigns credit

standing for that of the direct borrower,

the guaranteed party. The lender nds this

guarantee valuable because it is less likely

that the sovereign will miss a debt payment

than that the third party would. The usual

reason for the missed payment is a shortage

of funds. An example is a sovereign with AAA

credit rating guaranteeing a third party with

a CCC rating. The contingency to which the

sovereign is exposed in this guarantee is that

the direct borrower does not pay, on time and

in full, the debt-servicing obligation covered by

the guarantee. The size of the payment covered

by the guarantee at the time the contingency

materializes is the amount to which the

sovereign is exposed. That amount is specied

in the guarantee contract, and it might be

limited to one debt servicing payment or it

might extend to as much as the full outstanding

principal balance.

Another class of contingent obligations covers

specied conditions, such as certain acts

beyond any of the three parties control but

which in the end would likely adversely affect

the ability of the guaranteed entities to cover

their debt servicing obligations. Examples are

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

shortages of commodities, whether manifested

as literal shortages or extreme price increases,

foreign exchange rate instabilities, and civil

strife. The distinction between these two types

of guarantees is that in the former, credit

quality deterioration manifested by missed debt

service payments would lead to a call on the

guarantee without regard to cause.

In the domestic market, a credit substitution

guarantee might occur when small businesses,

agricultural enterprises or homebuyers borrow

from private nancial institutions. These are

examples of common three-party guarantees,

in which the borrower is the guaranteed party,

the sovereign is the guarantor, and a private

nancial institution is the lender. A private

institution is specied because it faces the

consequence of bankruptcy if it makes too

many loans to borrowers who do not repay

principal and interest. In a particular country,

weaknesses in sectors such as farming

and small business might imply frequent

interruptions in timely and full debt servicing

from such borrowers, which would prompt

private lenders to restrict amounts loaned,

limit repayment periods and charge high

interest rates reecting the high credit risk

premium. Those restrictions might be eased if

the sovereign were to backstop weaker credit

sectors with loan guarantees on the assumption

that the guarantees would generate net gains

for the public at large. This would require

that the gains to society resulting from the

guarantees more than cover the sovereigns

costs from the guarantees.

Finally, a fourth entity is sometimes involved

in sovereign guarantees when the sovereigns

own credit standing requires bolstering.

This is often the case with cross-border

transactions. An example might be a AAA

international corporation seeking nancing

for a project to be located in a country in

which the sovereigns own credit rating is

signicantly below AAA. An investors or

lenders project nancing terms typically

reect the probability of an interruption in

debt servicing associated with the weakest

credit, which in this example is the sovereign.

Under such conditions, the sovereigns own

guarantee would be backstopped by a guarantee

from an international nancial institution.

1-11

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

The sovereign might well conclude that the

public benet from the additional guarantee

would exceed that from any alternative use

of nancing from the international nancial

institution.

This illustrates another very important aspect

of the risk in contingent obligations the

currency in which the called guarantee must

be paid. In three-party sovereign guarantees

linked to the debt of domestic farmers or small

businessmen and owed to domestic private

nancial institutions, the currency of the

contingent obligation typically is the domestic

currency. The sovereign has control over the

supply of that currency, and is therefore able

to pay those claims whether by increasing the

money supply, displacing other government

expenditures, borrowing more or taxing more.

The macroeconomic effects of those choices

are not the same, of course, and the preferred

choice may not be the simplest politically.

But nonetheless, in three-party sovereign

guarantees, the sovereign has access to the

domestic currency to pay domestic contingent

obligations.

1.5.2 The Sovereigns Contingent

Obligations Costs and Risk

Exposure

Event risk is the term used to refer to the

risk that the contingency will materialize.

Contingent obligations are best managed when

the probability associated with event risk can

be forecast with reasonable assurance. Even

so, there inevitably is some margin of error in

calculating the probability of occurrence of the

kinds of events likely to be covered by sovereign

guarantees. Moreover, events triggering calls

on contingent obligations are linked to certain

macroeconomic conditions and neither they,

nor their linkages with calls on guarantees, can

be forecast with complete accuracy.

Some of the benets of a guarantee arise

precisely because of its contingent nature.

Because the guarantor has made a contractual

promise to pay, the guarantor rightly measures

his exposure to the risk of the guarantee

being called as equal to the amount promised.

However, for something less than a one-to1-12

Part 1 Risk Management

one chance of actually having a cash funding

obligation that is, for only the probable

amount called the sovereign can provide its

support to worthy projects or entities thereby

improving their access to funds or to favorable

funding terms. These benets from the

guarantee might translate to improved success

rates for the projects guaranteed, or to lowered

borrowing costs.

Probable amount called refers to the expected

cash obligation of the sovereign if event risk

materialized that is, if the guarantee were

called. The amount that would be owed

typically is specied contractually under the

guarantee, and is date-specic. The term

probable in this case therefore reects the

product of the probability of the events

occurrence (event risk) and the specied

contractual cash obligation owed at that time by

the sovereign should the event occur (exposure).

Probable loss refers to the probable amount

called on the guarantee, net of the probable

amount of funds, if any, subsequently recovered

by the sovereign from the guaranteed party. The

loss calculation might also include expenses

and some cost for the time value of money

depending upon the nature of the recovery.

Exposure refers to the total amount the

sovereign has promised to guarantee, and

therefore conceivably could be obligated

to fund. It is the maximum possible (not

probable) amount that can be called at any

point currently or in the future. Exposure is

an important risk measurement concept in

the management of contingent obligations. It

is the measure by which the guarantor tracks

its aggregate outstanding promises. As the

maximum guaranteed amount, it represents

the outer extreme of the total amount that

can possibly be called, and possibly lost. Its

probability is not zero. If there were absolutely

no chance a guarantee ever would be called,

the parties in the transaction would nd the

guarantee fee to be not worth paying, and

therefore the transaction would not have been

executed.

Guarantee fee is the compensation paid to the

guarantor for accepting the risks and costs

of a contingent obligation. Sometimes there

are enough independent guaranteed parties

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

and enough historical data to compute a fee

using an actuarial quantitative approach.

Such an approach would use a large number

of observations to measure probable calls

and losses, their time horizon and potential

impact on funding requirements. It would also

help determine not only the adequacy of the

guarantee fee structure but also the associated

reserves. A long-standing program of sovereign

guarantees on home mortgages would lend itself

to that actuarial type of analysis, for example.

The sovereign also might add a supplement to

the guarantee fee in order to limit any distortion

of competition in a market such as might arise

from extending sovereign guarantees to some

but not all participants.

1.5.3 Sovereign Contingent Obligations:

The Dynamics of Risk Exposure

The sovereign would want to evaluate the

benets and costs of contingent obligations in

terms of their dynamic or cyclical properties,

not just in a static analysis. The sovereign

assesses its contingent obligations in the

context of its responsibility to have in place

effective tools to manage such events if they did

occur. Moreover, probable calls on contingent

obligations should be included in projecting

a sovereigns borrowing program. Each

macroeconomic scenario used to project future

borrowing needs would likely entail a different

volume of calls on contingent obligations.

Any contingent obligation is expected to convey

a benet to the guaranteed party in terms of

a reduced cost of nancing, better nancing

terms, and/or improved access to funds. That

by itself is only a small part of the benet

test for the sovereign when evaluating these

instruments, although it is a prerequisite.

Benets from some contingent obligations are

difcult to quantify. The partial guarantee,

for example, leaves some risk exposure for

private lenders. This improves the credit terms

that they can provide while leaving them an

incentive to make sound credit quality lending

allocation choices. Another such benet is the

civil stability that can accrue from extensive

home ownership as a result of sovereign home

mortgage guarantees. Other benets more

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

readily lend themselves to measurement,

however. For example, extending the sovereign

guarantee to the debt of small businesses

might improve their viability by lowering their

debt servicing obligations. This might generate

enough associated increases in employment and

income tax revenue to more than compensate

for the sovereigns costs and risk exposure from

extending the guarantees.

The more important benet test for the

sovereign is the likely behavior of contingent

obligations in the context of the unique role

the sovereigns policymakers play on behalf

of the public in managing the macroeconomic

conditions in a country. Under adverse

cyclical conditions, for example, would calls

on contingent obligations exacerbate the cycle

or exert a counter-cyclical inuence? In a

crisis, would calls on contingent obligations

confound crisis management or would they

act as deterrents to further downward spirals?

Under such extreme circumstances, which

sectors in the economy would be protected by

the presence of sovereign contingent obligations

and which sectors or activities might be

damaged? Finally, what is the counter case:

using the same analysis of the extreme cyclical

circumstances or crisis conditions, what would

the results be for the payments system and

overall macroeconomic management if there

were no contingent obligations?

1.5.4 Managing Sovereign Contingent

Obligations

Questions about the costs and benets of

exposure to contingent obligations can be

answered through the insight gained from

a stress testing analysis of a portfolio of

contingent obligations. This approach helps in

evaluating the quantiable benets, risks, cost

and ultimate value to an economy of a sovereign

guarantee program. Stress testing is most fully

accomplished through a simulation model,

but if that is not feasible then even working

through the logic of a stress test is helpful. A

stress test analysis allows examination of two

very important attributes of potential calls from

contingent obligations: their covariance with

other cyclical patterns in the economy, and the

1-13

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

degree of concentration of these potential claims

that is optimal for macroeconomic management.

It illustrates these attributes because the stress

test takes an extreme case, even if it seems

unlikely, and works through its dynamics and

feedback effects.

When the sovereign contingent obligation

requires a payment in a foreign currency, the

risk analysis of the extreme or crisis condition

is a very crucial part of the sovereigns

evaluation because the foreign currency to

honor the called guarantee must be acquired

at a market price. In a crisis, that price can be

very high in terms of the domestic currency,

and this has been shown even in cases where

the domestic currency had been pegged

under pre-crisis conditions to a strong foreign

currency. Moreover, even when a contingent

obligation has the backstop of a fourth party,

such as an international nancial institution

that would lend the foreign currency to the

sovereign in order to pay the claim, there is a

need for very careful extreme-case risk analysis.

The analysis would consider the conditions

that would contractually permit exercise of the

contingent obligation alongside the plausible

extreme not just the likely macroeconomic

setting under which those conditions might coexist.

Evaluating and managing sovereign contingent

obligations requires careful dynamic risk

analysis. Not every contingent obligation

structure necessarily produces benets that

outweigh risks, although some clearly do.

The successful programs, even when costly at

times, have featured good macroeconomic risk

containment.

Successful management of sovereign contingent

obligations rests on a good quantitative base

built upon a solid information structure that

includes both called and contingent obligations.

That solid information structure underpins risk

analysis, reserves adequacy analysis and setting

the level of the guarantee fee. It helps measure

the linkage between the business cycle and the

cycle of calls.

1-14

Part 1 Risk Management

The Analytical Database recommended for

risk management and described later contains

modules for contingent obligations that

are designed to facilitate this analysis and

record keeping. The database would contain

information on each uncalled contingent

obligation as follows: the amounts associated

with the underlying debt guaranteed, the

guarantee obligation itself, the associated dates

and identities in the contract, and references to

the events covered by the contingent contract.

A time series section of the database would

store all this information for potential analytical

and ad hoc uses. The database also would

contain information on each called (exercised)

contingent obligation as follows. On each

measurement date, the amount owed directly

by the sovereign through calls would be detailed

in the appropriate section of the database

depending upon how the sovereign honored

the call. For example, if the sovereign borrowed

directly from a multilateral institution to honor

the foreign currency obligation of a four-party

guarantee, the relevant details would be stored

as a borrowing from a multilateral. The cash

ows associated with honoring each called

contingent obligation, as well as the relevant

details of the guaranteed entity and all dates

and amounts due, would be stored in the time

series section of the database.

Chapter 2 describes a simulation model that

further enhances risk analysis. These database

and risk measurement structures would lend

themselves to answering questions like:

Under alternative macroeconomic, scal

and market conditions, how much

additional funding would be required

from probable calls on guarantees? What

would be the impact on the funding plan?

How many calls on guarantees in a

particular economic sector (e.g., small

business) have occurred in the past? How

does the cyclical pattern of those calls

relate to the cyclical pattern of sovereign

funding needs in general? How much has

been recovered in the end from amounts

disbursed on called guarantees?

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1.6

Risk Tolerance and Performance

Measurement

Sovereign debt management involves using

the best generic portfolio and asset-liability

management standards. But in addition,

there are considerations of public trust and

macroeconomic management as well as

potentially complicated stakeholder involvement

associated with managing on behalf of the

sovereign. These all come together in the

topics of risk tolerance and performance

measurement.

For example, a private portfolio would be

managed to maximize return for any given

risk exposure, and will be structured to take

on certain risk exposures in order to earn

the associated returns. This is calculated

risk taking. But involved with that is some

probability of loss, which of course might

materialize. Also involved with risk exposures

are the uncertain events that can trigger losses

- these might include extreme political stresses,

nancial crises, international emergencies or

strife.2 When a private portfolio incurs extreme

loss, failure results and for the most part the

consequences of the failure are contained to the

stakeholders of that particular portfolio. There

is no such containment, of course, when the

portfolio is a public portfolio. Serious losses

can have major repercussions throughout the

economy. Moreover, households have no means

to hedge risks taken by the sovereign, but it

is they who ultimately bear the consequences

of the sovereigns risk exposure. With these

considerations, the public debt managers would

set risk tolerance goals that would incorporate

stricter loss avoidance and risk aversion than a

typical private portfolio.

The risk tolerances for public debt management

are complex. They are likely to reect a goal and

a hierarchy of constraints developed through

a consensus-building process among the

major stakeholders in the economy who stand

to gain from good public debt management.

These include the scal authorities; elected

Part 1 Risk Management

politicians; the central bank and the parties

involved in the conduct of monetary policy;

those elements of the economy who would be

most jeopardized by a nancial crisis; and the

segments of the public who would gain most

from stable, efcient domestic capital markets.

These of course, and others, also stand to lose

from public debt management that entails too

much exposure to crises or to volatility in debt

servicing requirements

For example, a set of risk tolerances for a

sovereign might be structured as follows.

First, minimize the risk of a funding shortfall:

that is, borrow the required volume of funds.

Second, minimize, to the extent feasible, the

risk exposure to undue volatility in debt service

requirements relative to funds available to

service debt: the relevant exposures would

include liquidity risk, market interest rate risk,

currency risk, counterparty and other business

partner risks. Third, undertake borrowing

operations consistent with those risk tolerances

that also limit rollover risk. Fourth, consistent

with the above, borrow funds at the lowest

feasible cost.

These, all reasonable statements and a

reasonable set of conditions for a sovereign,

would ultimately be focused on the cash ow

requirements. The particular focus would be

the near term, but their dynamic path over the

medium term, and their elasticity relative to

that of funds available to service debt, are very

important points of focus. This is one reason

why a benchmark that is constructed to focus

on an outstanding portfolio of debt can be

a very difcult tool for managing toward the

sovereigns goal.

There are several other reasons why a

benchmark constructed in terms of an

outstanding debt portfolio can cause difculties

for sovereign debt managers.3 The sovereigns

debt portfolio is unlikely to be actively managed,

so rebalancing an existing portfolio of funded

debt to accord with a benchmark focused

on portfolio characteristics is likely to be

The word crisis implies a special or infrequent condition. Financial crises associated with sovereign debt in the 1980s

and 1990s were by no means infrequent, however.

Paul Sullivan when he was director of Strategic and Risk Management for the National Treasury Management Agency of

the Republic of Ireland, said, all benchmarks should carry a government health warning.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-15

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

costly at the least. The likelihood of a need

to rebalance may be low if a sovereign has a

well-established debt management operation

and stable operating constraints. The chance

of needing to rebalance may be quite high,

on the other hand, for a sovereign whose

starting debt position is quite different from

the desired, and it is very likely to be high for

a sovereign in a transition status wanting also

to accomplish efcient market development.

Moreover, rebalancing a domestic debt portfolio

could interfere with market development. Even

with established, marketable, traded portfolios,

wrongly-constructed benchmarks can result in

perverse incentives and rewarding performance

that does not necessarily help to achieve the

goal; hence the title of a presentation at a

conference on benchmarks, Lies, Damn Lies

and Benchmarks.

Each country should establish its own risk

tolerances, goal statement and hierarchy

of constraints because the achievement of

macroeconomic objectives produces long-range

benets to the economy not accounted for in

the standard short-term cost/risk formulations

that benchmark commercial portfolio

performance. For example, domestic sovereign

debt is a macroeconomic tool that can affect

the functioning of domestic money and capital

markets. Also, a sovereigns foreign currency

debt can have implications for the exposure of

the economy to international market conditions.

Macroeconomic objectives such as these become

constraints in the framework for the sovereign

debt manager.

Especially where there is a transition

implied in market development, performance

measurement is more likely to be consistent

with the complex interaction of constraints

if a single benchmark portfolio concept is

avoided. Each sovereign would have its unique

hierarchy of constraints depending upon its

own starting position and time path for market

development. Well-constructed performance

measures can provide positive incentives and

a helpful framework for making choices that

are most consistent, all things considered,

with the sovereigns objectives. Given this

complexity, and the possibility that at times a

1-16

Part 1 Risk Management

set of constraints might contain some internal

conicts, performance measures that are

structured more like optimizing statements

than typical commercial portfolio benchmarks

are likely to be most useful. An example of the

overall statement is provided in the top section

of Table 1. This statement would likely be

unchanged for many years and is amenable to

being made public.

The sovereigns funding operation risk

tolerances and management guidelines are

likely to be quite specic, on the other hand,

and would evolve as needed or desired. The

specic tolerance ranges need not be publicly

stated, nor would they be expected to be as

stable as the overall policy statement. Perhaps

risk appetites or risk-bearing capacity might

change, for example, and that change would be

reected in the specic tolerances. The specic

macroeconomic considerations also would be

detailed, focused on achieving a near term goal

or satisfying near term constraints. Examples

of specic risk tolerance and macroeconomic

policy guideline topics are in Table 1. The

statements would be specic enough to provide

an operating framework for issuing debt and

evaluating the cost/risk tradeoff of alternative

funding choices. The statements likely would be

formulated by the risk management and policy

functions and endorsed by senior management.

These statements are the basis to measure

performance.

A tool for establishing these specic tolerances

is the dynamic simulation model, as described

in the following section and more fully in

Chapter 2. Extreme situations can be tested

and measured so that the potential risk

exposure linked to a cost reduction can be

evaluated. An example is the additional interest

risk exposure and funding risk exposure

associated with reducing cost, in a typical yield

curve environment, by issuing all short-term

debt.

The work underpinning the statement of specic

tolerances also can be helped by a thought

exercise. What is the case with no exposure to

funding and market risks? Each sovereign will

have its own answers to establish its own no

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

Part 1 Risk Management

risk hypothetical position. That starting point

helps in evaluating how much true value comes

from the acceptance of additional risk in return

for reduced cost, viewed in light of the countrys

own capacity to cope with risk exposure. The

context is the ability to honor each debt service

obligation, in full and on time.

Funds Available to Service Debt. How

sensitive is the net scal decit, excluding

interest payments, to economic conditions?

How tightly are interest payments on

outstanding sovereign debt linked to current

market conditions?

Funding Risk Exposure. What is the size of

the current and projected scal decit, and

the need for net new funding? How evenly

are principal payments due on outstanding

debt spread throughout the next ten years

and what is their size relative to the typical

volume of debt issued in that countrys

capital markets?

Market Risk Exposure. What is the currency

composition of the countrys source of funds

available to service debt? How much does

that vary under different market conditions?

What is the currency composition of the

countrys debt servicing obligations? What

is the net difference between the sources

and uses of funds in each currency, and

how does each net amount respond to

changing economic and market conditions?4

Similar questions are asked about the net

responsiveness of the funds available to

service debt and debt servicing with respect

to market interest rate changes

Credit Risk. Are there counterparties in

swaps or related transactions? Are there

contingent obligations outstanding but

not yet exercised? Are there on-lending

contracts?

This measure of risk, the currency-by-currency net difference between sources available to service debt and debt service

payments owed, is illustrated by the denition of a sovereign debt crisis: when the sovereign has insufcient funds to

supply or to purchase the currency needed for a debt service payment.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-17

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

Part 1 Risk Management

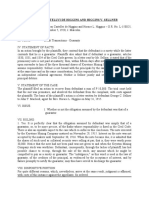

Table 1

Sovereign Goal and Policy Guidelines

Example of Public Statement of Goal for Sovereign Debt Management:

To provide the required funding volume in a scal year, in an orderly way that does not

compromise the ability to do that again in the coming year, and at lowest cost consistent with

guidelines and policies.

(1) Funding operations would be conducted within risk tolerances as dened by policy

guidelines. (Guidelines would be specied.)

(2) Funding operations would be subject to macro-economic considerations established by

policies with regard to cyclical stability and domestic market development. (Policies would

be specied.)

Example of Internal Guidelines for Risk Tolerances:

Subject to remaining within [specific tolerance range] of policy/risk management limits for:

(a) the currency composition of future debt servicing requirements over the medium term

horizon

(b) the interest rate resetting pattern over the coming [ve] years

(c) the overall annual debt amortization prole over the coming [ve] years; and

Other [specied in detail] considerations, as established by risk tolerances and other

macroeconomic objectives, such as:

(a) using instrument designs and marketing procedures that enhance liquidity and

marketability

(b) limiting credit risk exposure [with respect both to volume and minimum credit rating],

especially with regard to external entities

(c) using settlement and internal operating procedures that limit exposure to operational

risks.

Example of Policies for Macroeconomic Considerations:

Subject to [specied approaches] to funding so that it is consistent with offering debt regularly

and predictably in order to:

(a) enhance primary and secondary markets

(b) maintain market liquidity

(c) maintain the risk free status of sovereign obligations

1-18

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

1.7

Procedures for Managing Market

Risks and Returns

Using the tools and conceptual framework

described above, asset-liability managers are

able to establish processes and incentives to

help achieve their portfolio goal within their

constraints. They are able to measure the

performance of portfolio managers in that

framework, having been able to inform the

managers ahead of time what that framework

is i.e., with clear denition of the goal and

limits. They can measure performance returns

adjusted for risk, and ultimately can judge how

close their managers are to the efcient frontier

in their market risk class.

Thinking about sovereign debt management as

having some features that are macroeconomic

in nature but others that are shared by

managers of any nancial portfolio helps

to identify sources of value added from

providing technical assistance to sovereign

debt managers. The aspect of sovereign

debt management that carries all the same

hallmarks as any generic portfolio management

can benet from best practices and tools that

have been most reliable during the recent

general upgrading in quantitative nancial risk

management.

There is a strong case for relying on those

existing systems to the extent feasible.

They have a proven track record. Moreover,

introducing sovereign debt managers to best

practices, and helping them to use these tools

in an appropriate way, is in the end a very

efcient form of technical assistance. The tools

and approaches may involve a considerable

5

Part 1 Risk Management

initial investment, both in money and technical

effort, however. Accordingly, some of the

technical assistance to sovereign debt managers

would likely take the form of helping them plan

the steps in the transition to a fully quantitative

risk management and measurement system.

The market risk measurement system has

several components. Two components are the

structure of the data architecture and the use

of hardware and software appropriate for the

risk management and accounting/transactions

needs. The tools for making projections and

risk evaluations are a third component, and

the optimizing tool for measuring tradeoffs is

another. These are discussed below.

Projections for planning purposes, for

evaluating the risk/cost attributes of alternative

strategies, and for stress testing all can be

accomplished through a simulation model.

This procedure is becoming standard for

nancial risk management.5 The simulation

model is fed from the Analytical Database and

uses exogenous variables to depict market

conditions such as for interest and currency

exchange rates, and to depict other exposures

such as funding, liquidity and credit risks. The

simulation model is the tool for measuring the

value at risk, the extremes of risk exposures,

and the dynamic testing of risk-bearing

capacity. Chapter 2, Dynamic Simulation

Model for Sovereign Debt Risk Measurement,

describes this procedure. A simulation model

can be designed as a generic tool for sovereign

debt risk measurement. However, any such

model and its use can be complicated, and the

best technical support would come from helping

Optimal Bank Supervision in a Changing World by Alan Greenspan, The Declining? Role of Banking May 1994,

Thirtieth Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Chicago Federal Reserve Bank.

A Survey of Stress Tests and Current Practice at Major Financial Institutions: report by a Task Force established by

the Committee on the Global Financial System of the Central Banks of the Group of Ten Countries, April 2001. Bank

for International Settlements. available at www.bis.org. Forum for Central Banks, Committee on the Global Financial

System.)

Stress Testing by Large Financial Institutions: Current Practice and Aggregation Issues, April 2000, Committee on the

Global Financial System, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, Switzerland (available on www.bis.org. Forum for

Central Banks, Committee on the Global Financial System.)

Standard of Practice on Dynamic Solvency Testing for Life Insurance Companies, Canadian Institute of Actuaries, June

1991. available at www.actuaires.ca.

Bank for International Settlements release, May 21,1996, Basel Committee/IOSCO Ensuring that Banks Have Adequate

Capital. www.bis.org.

A Universal Approach to Credit Analysis. Moodys Investors Services at www.moodys.com.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

1-19

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

the country team to ultimately own its model.

This would be accomplished by providing a

generic set of equations, a fairly standard set

of exogenous variables, and perhaps even a

standard set of output tables and charts. But

these are best provided in a way that helps

assure that the country team does its own

programming and tailoring of the generic to suit

its own needs and learn from the ground up

how the model works.

A fully quantied risk measurement system

will have a structure for evaluating choices

and for trading off among alternative cost/risk

portfolio positions. This structure for evaluating

choices could be achieved by an explicit model

that measures these tradeoffs and that solves

for an optimal portfolio taking into account

the goal, constraints and available choices.

Such a model is complicated to build and

maintain, however. It moreover requires a fairly

high technical prociency among decisionmakers. And most importantly, an explicit

optimizing model is of no practical use if the

sovereigns own debt data, and the sovereigns

own strategic objective, are not available to be

incorporated. This point highlights the notion

that there is a critical path in developing good

measures for portfolio management.

Even if there is no explicit model to solve for

the optimal portfolio, it is possible to structure

the approach to making choices within this

risk management framework. Articulation of

the goal and constraints, and the desired time

path to achieve a certain goal, as described in

Section 2 of this chapter, are the rst step in

any case. The sovereigns own debt data must

be available in a sufciently detailed form for

risks and opportunities to be measurable. The

current choices available from the market

in other words, the interest costs for each

maturity class, for each type of instrument,

in each currency also are needed in any

case. Successive simulations, while not

Part 1 Risk Management

directly solving for the optimal portfolio, can

show the dynamic time proles of costs and

risks under many alternative future market

conditions. These results can then be used to

make choices within the tolerance ranges of the

existing framework; they also can be used to

inform further development of policies and risk

tolerances.

1.8

A Structured Approach to

Organization and Information

Architecture

There is a methodology with a well-proven track

record used to analyze the data and information

technology needs of an organization that

also provides an analysis of the organization

structure for conducting business. Experience

has shown that this business process can be

applied to all institutions in the public sector

and all industries in the private sector because

the requirements for developing information

systems are similar regardless of the business

served or the products and services provided.6

This information architecture methodology

starts from the premise that information

technology objectives should support an entitys

business objectives. For any given business

objective, the business process and data

requirements are relatively stable.

The structured approach discussed here

identies objectives, needs and priorities

largely through interviews with managers at

all levels. Results of these interviews are used

to establish a framework of the processes

and data requirements, and ultimately the

information resources, needed to serve the

business objective. Many organizations

have found that this structured approach to

information strategy planning also has yielded

valuable insights into business organizational

improvements. This process yields results

needed for both quantitative market risk

management and for operational risk

management.

From Information Systems Planning Guide, which offers assistance to teams conducting a Business Systems Planning

study, copyright International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), Third Edition, July 1981. This approach was used

initially in the 1960s for internal corporate business planning at IBM. It has been rened and used successfully among

a wide group of entities. By now, many professional practitioners in strategic information planning and information

engineering use procedures emanating from this original approach and an extensive literature is available.

1-20

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

The interviews determine each managers

opinions on the following:

1.

The key responsibility of each manager;

the most important objective in the

key areas he/she manages relating to

output of the organizational unit and

management processes.

2.

How personal success is measured and

dened.

3.

Critical success factors and the

information needed to enable success.

4.

Major obstacles or problems inhibiting

achievement of the objective, and his or

her suggested remedies.

5.

Specic items of information needed

to support each business process in

which the manager is involved; where

the information originates; adequacy

of information; and an opinion of the

benets of gaining access to available

information not already received.

6.

Likely future changes in the objective,

business process, organizational structure

and outputs in the managers area of

responsibility.

The compilation of the results of these openended interviews produces output including:

1.

Mission statement.

2.

Detailed list of functions performed and

the associated processes. For example,

borrow money is a function and the

associated processes could be develop

borrowing needs, issue debt, manage

outstanding debt portfolio, pay debt

service, etc.

3.

List of business process denitions. For

example, report nancial condition

could be dened as prepare mandated

and routine information and reports on

nancial condition and performance

for external and internal uses such

as audited nancial statements and

prospectuses.

Chapter 1 Risk Management for Sovereign Debt

Part 1 Risk Management

4.

Data entity type denitions. For example,

borrowing instrument could be

business agreement by which funds are

raised and which results in a liability.

5.

Business area identication and

denitions. For example, risk

management is a business area that

could be dened as the processes and

data used to manage nancial risk

exposures.

6.

Data collection denitions or subdatabases. For example, common

data might be dened as a data set

commonly used by many functional areas,

processes and application systems, such

as exchange rates, information about

counterparts, and macroeconomic data.

7.

Inventory of application systems. For

example, those that compute daily market

values for debt obligations, using daily

market prices.

8. Matrix of business processes and the

application system each uses.

9. Matrix showing each business process and

the organizational unit involved and its

degree of responsibility.

10.

Matrix showing each business process,

the data associated with the business

process and whether the data involvement

is to create the data or only to use it.

The matrix referred to in (10) above can be

thought of as a map showing where the data

are generated and where the data are used.

This map is essential in building an integrated

data/information system that will support

quantitative risk management as well as the

requirements for the General Ledger and

transactions processing.

These structured interviews bring to light areas

of responsibility for a subject or process and the

linkages of that organizational unit with other

parts of the organization that have subsidiary

responsibilities or dependencies. This output,

the matrix in (9) above, also can be thought of

1-21

Sovereign Debt Risk Management

as a map. In this case, the map yields valuable

insights into the nature of operational risks and

any gaps or redundancies in the organizational

structure that would need to be corrected to

minimize operational risk. This lends itself to

an action plan with appropriate assignments.

In particular, the process of producing these

maps through interviews with all managers

helps to generate their feeling of ownership

of the action plan and their support for its

successful conclusion.

This methodology can be especially valuable

in a setting in which such a structured

approach has not yet been applied. Many

countries now working on improved methods

for measuring and managing their sovereign

debt are examples. Typically, they are starting

from a position of fragmented institutional

responsibility for issuing sovereign obligations;

in many cases multilateral debt, guarantees,

foreign currency private market debt and

domestic currency obligations are all handled

by different units of government. Those

divergent responsibilities often are associated

with incompatibilities in data structures and

data handling standards across organizational

units, and with difculties in data sharing at

many levels.

Part 1 Risk Management

1.9

Organization Structure

The debt management system of any country is

complex. Many functions are interdependent

and performed by a number of government

agencies. Effective debt management requires

a clear allocation of responsibility and tasks

among agencies and smoothly functioning

relationships between the units involved.

Fortunately, however, many of the

considerations that are most signicant in

designing an appropriate organization structure

are common to any nancial management

function. Accordingly there are well-dened

best practices and a broad base of regulatory,

nance and academic literature on which

to draw. For example, an entirely different

approach to risk management comes into play

in managing exposure to the legal, regulatory,

underwriting and control risks of issuing debt.

A robust organization structure helps limit

exposure to some of these risks, as described

below. Well-designed accounting, cash

management and transaction databases and

procedures also help. Experienced legal advice

is necessary, as is advice on individual markets

and managing market presence.

The potential to use this methodology for

providing technical assistance to countries

in their sovereign debt management can be

summarized as follows. Each country will

have its own unique starting position in terms

of data quality and data processing tools, its

own unique data map and its own unique