Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Albert Hourani Islam, Christianity and Orientalism

Încărcat de

Chenxi DingTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Albert Hourani Islam, Christianity and Orientalism

Încărcat de

Chenxi DingDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

British Society for Middle Eastern Studies

Albert Hourani: Islam, Christianity and Orientalism

Author(s): Derek Hopwood

Source: British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Nov., 2003), pp. 127-136

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3593219 .

Accessed: 20/05/2013 11:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and British Society for Middle Eastern Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (November,2003),

30 (2), 127-1 3 6

30(2), 127-136

Albert

and

CarfaxPublishing

& Francis

Taylor

Group

ac

Hourani:

Islam,

Christianity

Orientalism

DEREK HOPWOOD*

(In memory of Albert Hourani, dedicated to Odile Hourani)

Albert Houranidied in January1993 after a lifetime devoted to the study of the

Middle East and Islam. This articleis an attemptto assess some of the influences

that helped to shape his intellectualand academic life and work by someone who

was his studentand then colleague for many years. On his death 'I felt as if part

of my own life had ended. As long as the teacher lived, one thought of oneself

as his student'.1

Looking at the whole of his life it is possible to single out three majorphases.

(1) His early life. He was born in Manchester,England,of Lebanese immigrant

parents. His family had been converted from Greek Orthodoxyto Scottish

Presbyterianism.Hourani often spoke of his family home in Manchester

where East met West, where many Lebanese and Arabs would gather, and

where his father was an elder of the local church. His brotherCecil wrote

about this period in his autobiographyand Albert himself wrote two shorter

biographicalpieces that mention it briefly.2He attended school at Mill Hill

near London and university at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he read for

a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

Then

a stay in Beirut, Cairo and Jerusalem in the 1930s and 1940s

(2)

introduced him to contemporaryIslam and to modem Arab nationalism

(about which he wrote a lot but with which I shall not deal here). He met

regularly with a group of fellow Lebanese in Beirut who discussed the role

of Arab Christiansin the Middle East and theirrelationswith Arab Muslims.

Charles Malik was a leading member of the group.

(3) Finally, his long period in Oxford that brought him into contact with

scholars there, particularlyHamilton Gibb, Professor of Arabic, and the

European orientalist scholar-emigres-Walzer, Schacht and Stem-who in

turn introducedhim to other Europeanorientalists,particularlythe FrenchCahen, Massignon, Berque. In addition to being influenced by the scholarship of these men he was deeply impressed by the spiritualityof three of

them-Gibb, Massignon and Berque.

* EmeritusReaderin ModernMiddle EasternStudies at St

Antony's College, University of Oxford, UK. This

paper was originally given as a lecture at St Antony's in January2003 to mark the 10th anniversaryof Albert

Hourani's death.

1 A.

Hourani,Islam in EuropeanThought(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1991), p. 37, quotingIgnaz

Goldziher on the death of his teacher, Fleischer.

2 C. Hourani.An

UnfinishedOdyssey;Lebanonand Beyond (London:Weidenfeldt, 1984). T. Naff (ed.) Paths

to the Middle East; TenScholarsLookBack (Albany:SUNY, 1993), pp. 27-56; N.E. Gallagher(ed.) Approaches

to the History of the Middle East; Interviews with Leading Middle East Historians (Reading: Ithaca, 1994),

pp. 19-45.

ISSN 1353-0194 print/ISSN1469-3542 online/03/020127-10 ? 2003 BritishSociety for MiddleEasternStudies

DOI: 10.1080/1353019032000126491

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEREK HOPWOOD

In all of Hourani's scholarly writings we find there are two broad general fields

of interest:firstly, the study of Middle East history that culminatedin his major

book A History of the Arab Peoples;3and secondly, studies on aspects of Islamic

and Arabic thought, on how Arab thinkers, Muslim and Christian,absorbedor

rejected European ideas and on how European orientalist scholars interpreted

Islamic history and religion. This latter topic seemed to engage his mind in his

later years quite considerably. His last published work was Islam in European

Thought, a collection of papers that contained his final lectures with the same

title.

Houraniwas a committedChristianand it is clear that his faith played a major

role in the way he approachedhis work and in particularhis study of Islam. A

fascinating aspect of his Christianlife was his conversion to Catholicism. It is

clear that in the late 1930s, in Beirut, he was deeply interestedin religion as his

attendance at discussions on Christianity in a group with Charles Malik and

others demonstrates. 'In the American University [of Beirut] there is the

movement for the creation of a Christian philosophy in Arabic, which is

associated with Charles Malik, Professor of Philosophy in the University, so far

almost unknown but perhaps the greatest intellectual figure in the Arab world

today.'4 I am not sure whether at this time he had abandonedhis family faith.

Conversion to Catholicism is not uncommon amongst intellectuals but it is not

clear what it was in particularthat attractedhim. His friend at Oxford, Charles

Issawi, the Middle East economic historian,discernedhis interestin Catholicism

very early and claimed that 10 years before Hourani's conversion he had laid a

bet that he would convert. Was it the influence of Charles Malik? Was it the

structureof the Church he found satisfying? Was it the cultural and spiritual

aesthetic or the intellectualrigour?There can be two kinds of conversion and of

faith in general. One is the emotional experience, the claim to have had a direct

experience of God, and there is the more intellectual assessment of faith that

leads to commitment. I think that Hourani agreed with the notion of Cardinal

John Henry Newman that faith is an act of intellectual assent, made under the

discipline of self-control, prayer and right direction of the heart. Faith is not

simply blind assent. Man strives after a vision of God about which humanreason

continuously asks all the relevant questions. Hourani must have asked these

questions and come to the conclusion that to follow the path of Newman

(himself an intellectual convert to Catholicism) was the most satisfactory

answer.

Houranispoke about aspects of his faith in a sermonhe gave in the University

Churchof St Mary the Virgin as universitypreacherin 1976. I do not know how

university lay preachers are chosen or how it is known that certain people are

suitable, but Hourani used the occasion to speak both about his own faith and

about how it had influenced his attitudetowards work and towards other faiths.

It is interesting that he based most of what he said on the thoughts of John

Henry Newman, who had often preachedin St Mary's (as an Anglican). He said

that the title of his own sermon could have been 'On presumingto stand where

Newman stood' and added that 'echoes of his words will be heard in everything

3 A.

Hourani,A History of the Arab Peoples (London: Faber and Faber, 1991).

4 A. Hourani, 'GreatBritain and Arab Nationalism 1943', unpublishedreport,pp. 84-85.

128

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALBERT HOURANI

I have to say'.5 He was, he said, like Newman and many others, engaged 'in the

search for a faith ... by which we can live'.6 He found that faith, or, as he said,

he found the Kingdom of God and enrolled himself in it. His faith and his work

became intertwinedand the one influencedthe other. One of the most unperceptive things I have ever read in a biography is Abdulaziz al-Sudeiri's comment

in his biography of Hourani that 'Although the conversion proved to be an

importantsustainingforce in his life, it did not appearsignificantlyto recast his

scholarly writing and outlook'.7

For Houranithe ultimate reality was the voice of God speaking to the human

soul and to the individual conscience, the voice which guides one to exercise

tolerance, to live in peace with others, to a charity of forgiveness-and in his

studies he twice quoted Pope GregoryVII's words on the charitywe owe to one

another.8The ultimate goal of life for the believer was union with God and the

final reality was the isolated soul in the presence of God. Here we have echoes

of Newman's great poem on the journey of the soul to God-'The Dream of

Gerontius'.

Take me away, that sooner I may rise and go above,

And see Him in the truth of everlasting day.

There is a striking passage in his sermon about what Houranicalls the religion

of Islam at its highest-that is, in Sufi thought.He says: 'All createdthings have

descended from the Divine Source in successive stages, and all strive to return

to that source; men, moved by their love of God, may ascend ... through the

world of images, to the courts of God'.9 This is the point where his vision of

Islam comes nearest to his vision of Christianity. But Christianity has that

essential extra dimension which is God himself descending and appearing in

flesh and in spirit. He wrote in 1955: 'It can mean nothing to say God became

Man, if we do not mean that He became one particularman'.10

This extra dimension that distinguishes Christianityfrom other religions gave

Houranithe certaintyof faith that he had writtenabout so forcefully in his earlier

years. Later, he became more reticent and one no longer found the bold

sentiments expressed in his first works that took one aback by their forthrightness and by the fact of their being used by a historianin particularnon-religious

contexts. Influencedby the views of the Beirut group, which, he wrote, regarded

'the Lebanese and Syrian Christiansas having a special mission ... to re-state

Christianityin Arabic, to stand for it in the face of the Moslem world'.ll It was

almost as though he felt threatenedand that he had to respond proportionately.

For example, in 1946 he wrote: 'Every human community must, if it would

avoid falling into mortal sin, make itself servant of something higher than

itself'.12Again, a little later, writing on racism: 'The idea that there is a moral

5 A. Hourani,Unpublishedsermon delivered in Oxford, 1976.

6

Ibid., p. 3.

7 AbdulazizAl-Sudairi,A Visionof the MiddleEast; An IntellectualBiographyofAlbert Hourani (London:I.B.

Tauris, 1999), p. 27.

8

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,pp. 9, 60.

9 Hourani,Sermon, p. 11.

10 A.

Hourani,A Vision of History; Near Eastern and other Essays (Beirut: Khayats, 1961), p. 26.

11 A. Hourani,Syria and Lebanon;A Political Essay (London:Oxford University Press, 1946), p. 265.

12

Ibid., p. 119.

129

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEREK HOPWOOD

and intellectualgradationamong humanbeings ... implies that Christdid not die

for all of us all alike'.13

Faith gave him a clear patternfor his life and he lived up to it-remembering

of course the human weaknesses all are heir to. He said (in his sermon) that he

wanted to make clear to himself and othershis vision of life, leaving it to others

to judge him. This had profoundimplications for his personal and working life.

He was very sure of the place of religions in the world. 'Certain groups of

modern educated Arabs ... regard Islam and Christianityas mere survivorsof a

dark age, and ... look forward to their imminent extinction ... This hope is vain.

Revealed religion cannot vanish from the world to which it has broughtlight.'14

This certaintythat faith gave influenced his historical writing and gave him an

approachthat others may not have had-a concern with and a readinessto define

the concept of truth. He believed that an organizing principle of historical

thought could be Truthand defined Truthas what people believe.15If that is the

case then there must be many truths,yet truthwith a capital T implies that there

is only one truth,i.e. Christianity.A strongbelief must lead one to question the

'truths' of others, for as he wrote: 'If I affirm anything I am necessarily

excluding something else'.16

The Christian scholar of Islam has to find an acceptable method of writing

about his subject. Islam and Christianityhave found (find?)it difficult to give an

intelligible place to the other within their systems of thought. Hourani wrote

notably of the look of 'uneasy recognition' with which the two religions have

always faced each other.17He approachedthe other religion as a responsible

Christian scholar with, he wrote, a sense of a living relationship with those

whom he studied. There was a need to stretch out across the gulf created by

power, enmity and difference. In a real sense, he asserted,dialogue should be at

the heart of our studies.18

In the days of his stay in Beirut he had not been averse to expressing

prescriptive, bold opinions that aimed to set an agenda for Muslim-Christian

relations. For example, he claimed: 'The whole future development of the Arab

countries depends on a change in the spirit of Islam', in its 'living creative

spirit'.'9 In those days he saw in the relationshipbetween Arab Christiansand

Muslims only the 'contemptuoustolerationof the strong [Muslim] for the weak

[Christian]',a situation,he said, that must be changed. How could it be changed?

By absorbing differences into a deeper unity, in a mutual love for God that

would lead to 'a sort of humility and forgiveness'.20 The two sides, he wrote, had

to engage in a dialogue of fruitful tension. I do not think that in his later years

he would have insisted so openly on a change in Muslim attitudes, nor on the

possibility of a deeper unity in love.

In his sermon he set out three ways of approachingthe religion of the other.

13

Hourani, Vision of History, p. 110.

14 A.

Hourani,Minorities in the Arab World (Oxford University Press, 1947), p. 124.

15

Approaches to the History of the Middle East, p. 39.

Gallagher,

16

Hourani, Vision of History, p. 27.

17 Hourani,Europe and the Middle East (London:Macmillan, 1980), p. 4.

18

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 89.

19 Hourani,Minorities, p. 123.

20

Ibid., p. 125.

130

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALBERT HOURANI

(1) The way of argument,of trying to persuade others that our beliefs are the

only true ones. This is rather the way of missionaries.

(2) By trying to extract the common features of the two religions.

(3) Through what he termed 'witness', by which he meant making clear what

he believed and leaving it to others to judge the value of his writings and

of his faith.

He found confirmationof these three approachesin the writings of Newman,

who claimed that:

(1) The way of argumentcan only show that controversyis superfluous(if we

all understandeach other) or hopeless (if we cannot change our views).

(2) Trying to extract common features may lead to a situation where all

statements are accepted even if they contradicteach other.

need not dispute, we need not prove, we need but define. This latter is

We

(3)

surely the way of witness that Hourani adopted, attempting to define as

clearly as he could and leaving others to judge the value of his work.

The defining of another'sreligion must be done with reverence and respect, the

reverence of a Christianand the respect of the serious scholar. Houranichose to

write about Islam at what he called 'its highest', i.e. as taught and practisedby

the trained 'ulama' and as expressed by some Sufis.

He found many positive factors in Islam that strengthenedhis respect for it as

faith and a way of thought;they are humanfactors, however, as he stoppedshort

of ascribing direct divine inspirationto Islam. In general, he believeed that all

cultures producedby the human spirit have value and that their ideas should be

treatedwith respect. Islam is equally a manifestationof the human spirit, a form

of human reasoning in the attemptto know God, a valid but limited response to

the Truth.One can admire a virtuous Muslim life and treat with respect Muslim

scholars who revere the Qur'an, but in the end one cannot go as far as to see

Islam as an alternative form of salvation. In support of these views Hourani

quoted the formulationsof the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) in defining

its attitude towards Islam. 'The Church looks with esteem upon the Muslims,

who worship the one living God ... who has spoken to men'.21 But behind this

statementthere lies of course the Roman Catholic certaintythat the one God is

the ChristianGod of the Vatican.

In his scholarly life Houraniwas deeply impressed and influenced by numerous other sensitive thinkers (mainly orientalist scholars) who could not dismiss

Islam out of hand22and who had something valuable to say about it. He

immersedhimself in the works of men such as Goldziher,Massignon, Gibb and

Marshall Hodgson. Amongst the many concepts he quoted with approvalfrom

them and others there is a notable one from Ignaz Goldziher, the Hungarian

Jewish scholar: 'A life lived in the spirit of Islam can be an ethically impeccable

life'.23 In Louis Massignon, a French Greek Catholic priest, a man to his mind

of disturbinggenius, he found a mystical empathywith Islam, althoughhe could

not accept his view that Islam was a stage of Christianity;in MarshallHodgson,

an American co-follower of Massignon and Gibb, he found compassion; and a

21

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 40.

22

Hourani,Europe and the Middle East, p. 74.

23

40.

Islam in

Hourani,

European Thought,p.

131

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEREK HOPWOOD

certain inspirationin Robin Zaehner (Spalding Professor of EasternReligions at

All Souls College, Oxford), whilst unable to accept his claim that Muhammad

was a genuine prophet.He commented on this claim that for Christians'it is, to

say the least, a matterof doubt whether,and in what sense, the Islamic revelation

can be regarded as valid'.24

So for Hourani, Islam was not a divine revelation but was an encountered,

contemporary, living religion followed by millions across the world and a

religion with a history. Therefore,it could be described and analysed as it is and

as it had been practised and interpreted.From his many writings it is possible

to discover what for him were the essential features of Islam. At the beginning

of his A History of the Arab Peoples he describes a journey taken by the great

Muslim historianIbn Khaldunin 1382 from Tunis, where he was in the service

of the ruler, to Alexandria and Cairo, where he took a post with the Mamluk

sultan. He also visited Damascus,Jerusalemand Mecca. Ibn Khalduncame from

a family that had left SouthernArabia to settle in Andalusia. Hourani used his

life to point up several lessons, among which was the fact that the Muslim world

had a 'unity which transcendeddivisions of time and space'25and that within

that world there existed a corpus of knowledge 'transmittedover the centuries

by a known chain of teachers'. It was a moral communitythat continuedto exist

even when rulers changed and one that preserved its faith in one God; a

community that observed prayers, fasts and pilgrimage in common. Hourani

admired and tried to understandthis 'profoundlyunified' society that was able

to withstandoutside shocks by taking in what was of value and refining it. He

was influenced and, he admitted,moved by Gibb's vision of the Islamic umma

persistingthroughouthistory.26It was this vision that he triedto perpetuatein his

own work. Unity was more importantthandisruptivemovements and factorsthat

tended to disturbit. Ibn Khalduncould travel throughthis ummaunhinderedand

discuss points of law or theology in Arabic with fellow scholars in numerous

cities.

This was the Sunni world of Islam and it is clear that this is the world that

best representedIslam for Hourani.It was the steady world that kept a balance

between extremes-a world in which the 'ulama' slowly accumulatedtradition

and in which Muslims strove for moral perfection, where Islam could be

observed without let or hindrance. As he put it, it was a world in which the

Shari'a was followed, the way 'by which men could walk pleasingly in the sight

of God and hope to reach Paradise'.27

This very positive view of Islam entailed writing about it, as he said, at its

highest, and another feature that attractedhim was Sufism 'at its highest'. He

disliked the more mundane aspects, what he considered the almost commercial

exploitationof the Sufi tarnqas.The sincere dedicated Sufi followers he found to

be men of the highest motives, men who in every age kept the world on its axis.

Abu Hamid al-Ghazali-the twelfth century Islamic scholar-seemed to represent all that was best in the Sunni and Sufi worlds. He wanted to keep the

whole community on the right path by underliningall the moral implicationsof

24

25

26

27

Hourani,Europe and the Middle East, p. 74.

Hourani,History of Arab Peoples, p. 4.

A. Hourani,The Emergence of the Modern Middle East (London:Macmillan, 1981), p. xiii.

Hourani,Arabic Thought,p. 2.

132

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALBERT HOURANI

Muslim practices. Man's chief aim was always to draw nearer to God. While

perhaps not a full Sufi, Hourani saw in him all that was noblest in the Sufi

masters,whose aim was the 'utterabsorptionof the heartin the remembranceof

God'.28He quoted a sentence from Ghazali which does not sound very different

from Newman's Gerontius:'Worldlydesires began tugging me with their claims

to remain as I was, while the herald of faith was crying out, "Away! Up and

away!"'

29

Into the nineteenth century, Houranifound other scholars who had struggled

to preservethe ummain the face of the moder world. His book Arabic Thought

in the Liberal Age, 1798-193930 is a study of their responses to modernity and

it is interestingthat in the preface to the second edition he wrote that he should

have written a different book, one that emphasized continuity in the world of

Islam ratherthan a break with the past. There were at least two reasons for this

change of approach.Firstly, since the publication of the first edition a number

of studies had appearedthat stressed the continuity of Islamic thought in the

eighteenth century and he was very much influenced by them; and secondly,

continuity ratherthan change became more importantto him. He had, however,

singled out two scholars who had laid emphasis on preservingthe umma,Jamal

al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad'Abduh. Both had stressed that all the basic

principles of Islam were valid and that they had only to be observed meticulously for Islam to prosper. Although al-Afghani perhaps seemed a little rough

to Hourani, he saw in 'Abduh an ideal type of human being and Muslim: 'In

later years [his] gentleness increased, and those who knew him were conscious

of his kindness and intelligence and a certain spiritualbeauty'.31

Houranidisliked the violence or extremismthat lately disruptedthis world. He

called the last chapterof his History of the Arab Peoples, which dealt with the

post-1967 period, 'A disturbanceof spirits'. It was almost as though he shut his

eyes to violent change. In his early book on minorities he had expressed

misgivings about extreme Shi'ism and wrote that it was essential that the 'gap

between the different Islamic sects should be bridged',32although I think that

later he came to appreciatemore the positive features of Shi'ism, even writing

that he would place greateremphasis on the Shi'ite traditionthan had Gibb. This

view developed later under the influence of a numberof Shi'ite scholars whom

he got to know well.

The single most important aspect in the preservation of the Muslim community was, in Hourani'sview, the continuityof knowledge transmittedover the

centuries by a known chain of teachers-the famous silsila. He returnedto this

theme many times in his writings. In his autobiographicalsketch he says that he

was introducedto this concept by his colleague at Oxford, RichardWalzer, who

'taught me the importanceof the continuity of scholarly traditions:the way in

which scholarship was passed from one generation to another by a kind of

apostolic succession'.33There are two aspects of the silsilsa: the one referringto

the Hadith (the Muslim traditions)passed througha recognized chain, the isndd,

28

Hourani,History of Arab Peoples, p. 170.

29

168.

Ibid., p.

A. Hourani,Arabic Thoughtin the LiberalAge, 1798-1939 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1983).

31 Hourani,Arabic

Thought,p. 135.

32

Hourani,Minorities, p. 124.

33 Naff, Paths to the Middle East, p. 38

30

133

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEREK HOPWOOD

which Hourani admitted could be fabricated or faulty; and the other that he

valued in scholarly life, the relationshipof teacher and pupil and of colleagues.

He quoted Massignon, I believe with approval,that it is possible 'to hold a view

of history which sees the handing on of knowledge of God from one individual

to another as the only significant process, and therefore the process most

deserving of study'.34Hourani could see (with Massignon) this process in an

almost mystical light: 'History is a chain of witnesses enteringeach other's lives

as carriersof a truth beyond themselves.'35

In Islam the prophet Muhammad was the initiator of the chain of the

transmissionof knowledge. For the non-Muslim scholar of Islam the life of the

prophet has always posed the greatest problems of interpretation-in particular

the thorny question of whether he was the recipient of divine inspiration.We

have seen that Houranihimself did not accept a divine aspect to Muhammad's

mission, but to avoid causing offence, in his History of the Arab Peoples he

accepts that 'It seems best ... to follow the traditionalaccount of the origins of

Islam' but to do this with caution as there is room for scholarly discussion about

the way these beliefs developed.36We can see here a nod in the direction of

Crone and Cook's 'Haggarism',which caused such a stir on its appearancewith

their criticism of the traditional sources for the life of Muhammad. It is

interesting that in an earlier lecture given in 1974 he appearedto be still under

the influence of Haggarismwhen he said: 'Much of the traditionalbiography[of

Muhammad]begins to crumble if one looks at it closely and critically'.37

In a possible escape from having to deal with the theistic aspects of Islamic

history the historian can follow the advice of the Dutch scholar Snouck

Hurgronje,who suggested that Islam should be studied in its historical reality

without making value judgements about what it ought to be. This he extended

to the principle, with which Hourani agreed, of studying the society in which

Islam emerged and the societies in which it continues to exist, althoughHourani

believed that studying the societies of the different Islams was a task of the

social historian or anthropologist.He admired the work of scholars such as

Michael Gilsenan and others who stressed the specificity of different societies.

This was not the high Islam that Hourani sought but what he and others have

termed 'popular', the people's interpretation and observance of sometimes

non-orthodox practices. This led him to propose the principle that whatever

people believe to be Islam is Islam.38But he repeatedthat his 'intention... [was]

not to study these popular movements, but to confine [himself] to the high,

urban, literate traditionof Islam'.39

The final section of this paper deals with the third of the trinity of topics in

the title-orientalism. Hourani maintained a very deep respect for that much

maligned group of scholars-the orientalists-and felt uncomfortablewith some

of the stricturesin Edward Said's book Orientalism.When writing about Said's

theories he went almost as far as he could, without descending to polemics, in

criticizing them. He wrote restrainedlythat Said's methods of expression 'at

34 Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 97.

35 Ibid.

36

Hourani,History of Arab Peoples, p. 1.

37 Hourani,Europe and Middle East, p. 2.

38

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 101.

39 Ibid., p. 102.

134

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALBERT HOURANI

times bring him near to caricature'and that 'perhapshe makes the matter too

simple when he implies that [orientalism]is inextricablybound up with the fact

of domination'.40(Hourani often used the word 'perhaps' when he meant

'absolutely certainly'.) He is careful to give weight to some of Said's points but

regrettedthat the epithet 'orientalist' could no longer be used with the respect

he thought it deserved. As he wrote: 'The time has gone when orientalistscould

speak of themselves, without fear of contradiction, as contributing from the

He

purest of motives to the spread of knowledge and mutual understanding.'41

had an almost mystical regardfor the clan of orientalists-'priests of a mystery'

he called them-whose task was 'to lay [their]hands in reverence and devotion

upon ... the past'.42 They are all part of that silsila-of

orientalist scholars rather

than 'ulama'-into which any aspiring young scholar should insert him- or

herself. He believed that he did not form part of a chain himself and that he was

not an orientalist,but it is clear that he felt very much a colleague of the scholars

alreadymentioned.This feeling deepened as he grew older. Oxford, he felt, had

made no mark in Oriental studies until the arrival of Professor Gibb, together

with Walzer, Schacht and Stem. He in particularrevered Gibb. 'Behind us there

stood the great figure of ... Gibb ... even when physically absent he was spiritu-

ally with us, the murshid guiding our steps in different ways'.43 Walzer

introducedhim to 'the central tradition of Islamic scholarship in Europe, that

expressed in German'44-and so obviously omitted by Said. Stem seemed to be

the 'very embodimentof that tradition'.45These colleagues at Oxford strengthened the link with European orientalist scholarship-the Italians, the Germans

and the French. Two Frenchmenmade a deep impression, orientalistswith their

semi-mystical attachmentto the world of Islam, both, like him, Catholics. Louis

Massignon fascinated him, a man who seemed to dwell partially in another

place, with a vision of the mystical, a pilgrim as Houraniwrote, in a world that

was not for him. In a photographof him enteringJerusalemwith T. E. Lawrence

and the allied forces in 1917, Houranidiscernedin his eyes a man with a vision

of another Jerusalem.46That is, the Catholic vision of an orientalist. Hourani

found this too in Jacques Berque, the other Frenchmanwho had spent a lifetime

in the study of the Middle East. In a tributeto him, he picturedBerque devoting

his later life to the study of Islam, which was for him 'the "other", to be

apprehended and accepted in itself: a fitting task for a long and fruitful

retirement'47in his home village of St Julien-en-Bom, which as Hourani added

significantlylies 'on the road to Santiago de Compostela', a seemingly irrelevant

remarkuntil one realizes that for Hourani that city must have representedthe

ultimate goal for the Catholic scholar-pilgrim.

In his writings,Houraniremaineda strong defenderof the orientalisttradition.

He praised the work of the earliest orientalistscholars, showing that they wrote

and related to the world as they did as their minds were inevitably formed by

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

Ibid., p. 63.

Ibid, p. 62.

Ibid., 1.c.

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 61.

Naff, Paths to the Middle East, p. 38.

Ibid., I.c.

Hourani,Islam in European Thought,p. 116.

Ibid., p. 135.

135

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEREK HOPWOOD

the culture of their age and by the ideas and convictions their lives had taught

them. By and large they succeeded, often working in isolation and as pioneers

in difficult topics. They had to do many things and Hourani admittedthat it was

'not surprisingthat they did not do all of them equally well'.48Their knowledge

and use of oriental languages, often criticized as tools of imperialism,Hourani

considered to be liberating forces enabling them to penetrate different cultures

without ulterior motives. In general it is clear that he held the orientalist

contributionto knowledge as being much more positive than does Said, and he

wrote approvinglyof the scholars de Sacy, Lane, Massignon and many others,

so often criticized by Said.

How does one end this survey of another'slife, of a man who himself devoted

himself to the study of the other, of a man who made such a deep impact on the

lives of others? Hourani said that 'Edward [Said] once asked [the] question,

"How can one understandthe other?"One could answer, "One has to do one's

best".' But more than that I think he gave us a fitting ending, a fitting summary

of how he thought we should live and how we should relate to others in this

world. In the preface to the English translationof Jacques Berque's book Egypt;

Imperialismand Revolution,he asked: 'Is it possible to grasp the essential nature

of a country other than one's own? Yes, in the sense in which one can know a

human being other than oneself: throughpatience, clarity and love, and with a

final acceptance of the mystery of otherness'.49

48

Ibid., p. 35.

49 J. Berques, Egypt; Imperialismand Revolution (London:Faber and Faber,

1972), p. 7.

136

This content downloaded from 171.67.34.205 on Mon, 20 May 2013 11:46:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptDe la EverandPreaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iran Under Allied Occupation In World War II: The Bridge to Victory & A Land of FamineDe la EverandIran Under Allied Occupation In World War II: The Bridge to Victory & A Land of FamineEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Albert Hourani - Europe and The Middle East (1980, University of California Press) PDFDocument240 paginiAlbert Hourani - Europe and The Middle East (1980, University of California Press) PDFRizky Pratama100% (1)

- Early Islam - Lecture by Fred DonnerDocument8 paginiEarly Islam - Lecture by Fred DonnerilkinbaltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hourani, Arabic ThoughtDocument10 paginiHourani, Arabic Thoughtahmad_fahmyalfar75_6100% (1)

- Historiography & The Sirah WritingDocument4 paginiHistoriography & The Sirah WritingSyed M. Waqas100% (1)

- What Defines an ArabDocument15 paginiWhat Defines an Arabsparta3027955Încă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Middle East StudiesDocument16 pagini2016 Middle East StudiesStanford University Press0% (1)

- Contemporary Scholarly Understandings of Qur'Anic Coherence: KeywordsDocument14 paginiContemporary Scholarly Understandings of Qur'Anic Coherence: KeywordsSo' FineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutazilah or RationalDocument9 paginiMutazilah or RationalSirajuddin AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land For Peace: A Halachic Perspective: Rabbi Hershel SchachterDocument24 paginiLand For Peace: A Halachic Perspective: Rabbi Hershel Schachteroutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- Slavery in Early Islamic CivilizationsDocument40 paginiSlavery in Early Islamic CivilizationsJamalx AbdullahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Egyptian Democracy and The Muslim BrotherhoodDocument36 paginiEgyptian Democracy and The Muslim Brotherhoodpj9693Încă nu există evaluări

- Albert Hourani, The Changing Face of The Fertile Crescent in The XVIIIth Century (1957)Document35 paginiAlbert Hourani, The Changing Face of The Fertile Crescent in The XVIIIth Century (1957)HayriGökşinÖzkorayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ar 01 Lessons in Arabic LanguageDocument125 paginiAr 01 Lessons in Arabic LanguageMuhammad WahyudiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mamluk History: The Governor. Before Leaving Egypt, Selim Appointed A Renegade Mamluk, Kha'ir Bey, As TheDocument7 paginiMamluk History: The Governor. Before Leaving Egypt, Selim Appointed A Renegade Mamluk, Kha'ir Bey, As Thetimparker53Încă nu există evaluări

- Islam and International Criminal Law and PDFDocument270 paginiIslam and International Criminal Law and PDFaminah_mÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brinkley Messick The Calligraphic State Textual Domination and History in A Muslim Society Comparative Studies On Muslim Societies, No 16 1996Document323 paginiBrinkley Messick The Calligraphic State Textual Domination and History in A Muslim Society Comparative Studies On Muslim Societies, No 16 1996Fahad BisharaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Ayatollah Khomeini in the Iranian RevolutionDocument28 paginiThe Role of Ayatollah Khomeini in the Iranian Revolutionritik goelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cold War and The Middle East PDFDocument319 paginiThe Cold War and The Middle East PDFSyed Farzal Muyid Alim100% (1)

- From Seljuk To OttomanDocument7 paginiFrom Seljuk To OttomanJimGiokezasÎncă nu există evaluări

- All for Resistance: Paingraphy of the Deprived Movement and Groundwork of Hezbollah's RiseDe la EverandAll for Resistance: Paingraphy of the Deprived Movement and Groundwork of Hezbollah's RiseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Islam Compatible With Modernity?Document12 paginiIs Islam Compatible With Modernity?Firasco50% (2)

- Saudi Arabia The Rise of Transnational SDocument74 paginiSaudi Arabia The Rise of Transnational SPete ForemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Insurgents To Hybrid Security Actors? Deconstructing Yemen'S Huthi MovementDocument16 paginiFrom Insurgents To Hybrid Security Actors? Deconstructing Yemen'S Huthi MovementLuisa de CesareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baqir al-Sadr's Theory of Islamic DemocracyDocument28 paginiBaqir al-Sadr's Theory of Islamic DemocracyMohamed HusseinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial EgyptDe la EverandThe Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial EgyptÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biography of Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed TahaDocument6 paginiBiography of Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed TahazostriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Circuits of Faith: Migration, Education, and the Wahhabi MissionDe la EverandCircuits of Faith: Migration, Education, and the Wahhabi MissionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iran: The Impossible Revolution and the Limits of Revolutionary ZealDocument22 paginiIran: The Impossible Revolution and the Limits of Revolutionary ZealVlameni VlamenidouÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Approach To The Understanding of Islam - Ali ShariatiDocument16 paginiAn Approach To The Understanding of Islam - Ali ShariatiBMT-linkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rashid Khalidi Et Al. (Eds.) - The Origins of Arab Nationalism (1993, Columbia University Press) PDFDocument343 paginiRashid Khalidi Et Al. (Eds.) - The Origins of Arab Nationalism (1993, Columbia University Press) PDFReem ShamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science and IslamDocument2 paginiScience and IslamMoinullah KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fall of The Ottomans,' by Eugene Rogan - The New York Times - GugaDocument3 paginiThe Fall of The Ottomans,' by Eugene Rogan - The New York Times - GugaEder OliveiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Jundishapur School of MedicineDocument27 paginiThe Jundishapur School of MedicineJoko RinantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamic StudiesDocument197 paginiIslamic StudiesAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Intensive Animal FarmingDocument43 paginiIntensive Animal FarmingA. AlejandroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ayatollah Khomeini Is A Savak AgentDocument2 paginiThe Ayatollah Khomeini Is A Savak AgentAmy BassÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Islamic Obligation To Emigrate Al-Wansharīsī's Asnā Al-Matājir ReconsideredDocument497 paginiThe Islamic Obligation To Emigrate Al-Wansharīsī's Asnā Al-Matājir ReconsideredShaiful BahariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Domestic Violence in IslamDocument17 paginiDomestic Violence in IslamalmicicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Failures of The Late Ummayad Empire and Its FallDocument13 paginiFailures of The Late Ummayad Empire and Its Fallmmuraj313Încă nu există evaluări

- Socio-Political Turbulence of The Ottoman Empire: Reconsidering Sufi and Kadizadeli Hostility in 17TH CenturyDocument34 paginiSocio-Political Turbulence of The Ottoman Empire: Reconsidering Sufi and Kadizadeli Hostility in 17TH CenturyAl-Faqir Ila Rabbihi Al-QadirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Status of the Individual in Islam: An AnalysisDocument13 paginiThe Status of the Individual in Islam: An AnalysisRaoof MirÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Kingdom's Future: Saudi Arabia Through The Eyes of Its TwentysomethingsDocument170 paginiA Kingdom's Future: Saudi Arabia Through The Eyes of Its TwentysomethingsThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Living Under Muslim LawsDocument172 paginiWomen Living Under Muslim LawsLCLibrary50% (2)

- Beth Baron-Egypt As A Woman - Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (2007) PDFDocument304 paginiBeth Baron-Egypt As A Woman - Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (2007) PDFMarina مارينا100% (2)

- Technique of The Coup de BanqueDocument54 paginiTechnique of The Coup de BanqueimranebrahimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920De la EverandThe Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Curzon, N. - Persia & The Persian Question Vol 2Document745 paginiCurzon, N. - Persia & The Persian Question Vol 2APP30100% (1)

- برنامج الليبرالية الدولية - الوثائق الأساسية للاتحاد الفيدرالي العالمي للأحزاب السياسية الليبراليةDocument94 paginiبرنامج الليبرالية الدولية - الوثائق الأساسية للاتحاد الفيدرالي العالمي للأحزاب السياسية الليبراليةFriedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom Regional Office MENA100% (1)

- AHS B312 NATIONALISM IN AFRICA AND THE REST OF THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES JavanDocument25 paginiAHS B312 NATIONALISM IN AFRICA AND THE REST OF THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Javankennedy mboyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Somaliland leaders discuss cooperation with Turkey as Ethiopia outlines oil-revenue sharingDocument8 paginiSomaliland leaders discuss cooperation with Turkey as Ethiopia outlines oil-revenue sharingWargeyska SaxafiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Teleological Ethics of Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-RāzīDocument3 paginiThe Teleological Ethics of Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-RāzīhozienÎncă nu există evaluări

- Famous Women in Islamic HistoryDocument20 paginiFamous Women in Islamic Historyalqudsulana8980% (5)

- Philip Hitti Capital Cities of Arab Islam 1973Document185 paginiPhilip Hitti Capital Cities of Arab Islam 1973jorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saudi Arabia in The New Middle EastDocument64 paginiSaudi Arabia in The New Middle EastCouncil on Foreign Relations100% (1)

- Ibn KhaldunDocument25 paginiIbn KhaldunJony SolehÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Islamic Surveys) William Montgomery Watt, W. Montgomery Watt - Islamic Political Thought (The New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys) - Edinburgh University Press (1998)Document199 pagini(Islamic Surveys) William Montgomery Watt, W. Montgomery Watt - Islamic Political Thought (The New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys) - Edinburgh University Press (1998)abodeinspirationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morocco's Aborted Social Mobilization All Behind The KingDocument19 paginiMorocco's Aborted Social Mobilization All Behind The KingChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- David and Solomon and The United Monarchy, Archaeology and The Biblical NarrativeDocument4 paginiDavid and Solomon and The United Monarchy, Archaeology and The Biblical NarrativeChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Le Souverain Du Maroc, Législateur - enDocument50 paginiLe Souverain Du Maroc, Législateur - enChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marginality of The Sharia and Centrality of The Commandery of The BelieversDocument20 paginiMarginality of The Sharia and Centrality of The Commandery of The BelieversChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam and ScienceDocument3 paginiIslam and ScienceChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffee Break FrenchDocument111 paginiCoffee Break FrenchChenxi Ding100% (11)

- The Separation of State and Religion in The Development of Early Islamic SocietyDocument23 paginiThe Separation of State and Religion in The Development of Early Islamic SocietyChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Darija VerbsDocument7 paginiDarija VerbsChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demonstrating Islam The Conflict of Text and The Mudawwana Reform in MoroccoDocument21 paginiDemonstrating Islam The Conflict of Text and The Mudawwana Reform in MoroccoChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topics in The Archaeology of Jerusalem in Biblical TimesDocument6 paginiTopics in The Archaeology of Jerusalem in Biblical TimesChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION FIELD EXAM READING LISTDocument5 paginiISLAMIC CIVILIZATION FIELD EXAM READING LISTJj TreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New Anthropology of IslamDocument232 paginiA New Anthropology of IslamChenxi Ding100% (2)

- 9780415470766Document3 pagini9780415470766Valeria Maritaca RizzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Center For Arab and Middle Eastern Studies (CAMES)Document9 paginiCenter For Arab and Middle Eastern Studies (CAMES)Chenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Whose Tradition, Which DAO Confucius and Wittgenstein On Moral Learning and ReflectionDocument342 paginiWhose Tradition, Which DAO Confucius and Wittgenstein On Moral Learning and ReflectionChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Order of Places Translocal Practices of The Huizhou Merchants in Late Imperial ChinaDocument278 paginiThe Order of Places Translocal Practices of The Huizhou Merchants in Late Imperial ChinaChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Man Versus Society in Medieval IslamDocument1.181 paginiMan Versus Society in Medieval IslamChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Issues in Islamic StudiesDocument10 paginiCurrent Issues in Islamic StudiesChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diverging Paths The Shapes of Power and Institutions in Medieval Christendom and IslamDocument456 paginiDiverging Paths The Shapes of Power and Institutions in Medieval Christendom and IslamChenxi Ding100% (2)

- KosherDocument241 paginiKosherChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Define and RuleDocument165 paginiDefine and RuleChenxi Ding100% (1)

- Climate and Political Climate Environmental Disasters in The Medieval LevantDocument230 paginiClimate and Political Climate Environmental Disasters in The Medieval LevantChenxi DingÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New Anthropology of IslamDocument232 paginiA New Anthropology of IslamChenxi Ding100% (2)

- Nicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecDocument3 paginiNicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecJessamine OrioqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duah'sDocument3 paginiDuah'sZareefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating GrammarDocument8 paginiIntegrating GrammarMaría Perez CastañoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUDocument1 paginăSAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUXIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiple Choice Test - 66253Document2 paginiMultiple Choice Test - 66253mvjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corneal Ulcers: What Is The Cornea?Document1 paginăCorneal Ulcers: What Is The Cornea?me2_howardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ardipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoDocument5 paginiArdipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoBianca IrimieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Einstein HoaxDocument343 paginiEinstein HoaxTS100% (1)

- Cronograma Ingles I v2Document1 paginăCronograma Ingles I v2Ariana GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Med 07Document5 paginiMed 07ainee dazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Document3 paginiJason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Jason BrownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ice Task 2Document2 paginiIce Task 2nenelindelwa274Încă nu există evaluări

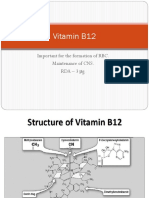

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDocument19 paginiVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao (Esp) Monitoring and Evaluation Tool For Department Heads/Chairmen/CoordinatorsDocument3 paginiEdukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao (Esp) Monitoring and Evaluation Tool For Department Heads/Chairmen/CoordinatorsPrincis CianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical StoreDocument11 paginiMedical Storefriend4sp75% (4)

- Coek - Info Anesthesia and Analgesia in ReptilesDocument20 paginiCoek - Info Anesthesia and Analgesia in ReptilesVanessa AskjÎncă nu există evaluări

- The "5 Minute Personality Test"Document2 paginiThe "5 Minute Personality Test"Mary Charlin BendañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rak Single DentureDocument48 paginiRak Single Denturerakes0Încă nu există evaluări

- Metabical Positioning and CommunicationDocument15 paginiMetabical Positioning and CommunicationJSheikh100% (2)

- Automatic Night LampDocument22 paginiAutomatic Night LampAryan SheoranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The ADDIE Instructional Design ModelDocument2 paginiThe ADDIE Instructional Design ModelChristopher Pappas100% (1)

- mc1776 - Datasheet PDFDocument12 paginimc1776 - Datasheet PDFLg GnilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning Levels and Types for Organizational SuccessDocument20 paginiPlanning Levels and Types for Organizational SuccessLala Ckee100% (1)

- New Manual of Fiber Science Revised (Tet)Document43 paginiNew Manual of Fiber Science Revised (Tet)RAZA Khn100% (1)

- New Titles List 2014, Issue 1Document52 paginiNew Titles List 2014, Issue 1Worldwide Books CorporationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hannah Money Resume 2Document2 paginiHannah Money Resume 2api-289276737Încă nu există evaluări

- Class 11 English Snapshots Chapter 1Document2 paginiClass 11 English Snapshots Chapter 1Harsh彡Eagle彡Încă nu există evaluări

- Enterprise Information Management (EIM) : by Katlego LeballoDocument9 paginiEnterprise Information Management (EIM) : by Katlego LeballoKatlego LeballoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DurexDocument3 paginiCase DurexGia ChuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portal ScienceDocument5 paginiPortal ScienceiuhalsdjvauhÎncă nu există evaluări