Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

I'll Do It My Own Way: Three Writers and Their Revision Practices

Încărcat de

daroksayDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

I'll Do It My Own Way: Three Writers and Their Revision Practices

Încărcat de

daroksayDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

STEPHANIE DIX

I’ll do it my way: Three writers

and their revision practices

Students approach writing and revising in were collected from semistructured teacher inter-

views, classroom observations of the writing pro-

different ways and are aware of the gram, students’ written scripts, and student

decisions that go into them. interviews during the writing process.

Writing is recognized as a cognitive process

C

lassrooms today present teachers with a and social practice (Clay, 1998; Dix, 2003a; Kress,

range of educational challenges. Diversity is 1999). In the writing classroom, teachers and peers

acknowledged and celebrated not only with provide a range of supportive learning and social

respect to the cultural and social differences that interactions around text (Calkins, 1991; Dix,

students contribute, but also in the diverse ways 2003b; Dyer, 1992; Dyson, 1989). However, while

that children learn in the classroom. The study in an investigation of teacher–student interactions was

this article profiles differences between three stu- part of this study, it is not the focus of the article.

dents and their writing and revision practices. This article discusses different ways students com-

The classroom-based research project this ar- pose and revise their texts.

ticle draws on was initiated by educational policy

reforms instigated by the New Zealand Ministry

of Education to improve the literacy levels of stu- The role of revision in the writing

dents. Of particular interest was the Report of the

Literacy Taskforce (Ministry of Education, 1999). process

It proposed that by the year 2005 all 9-year-old The research literature regards the ability to re-

children would be successful readers and writers. It vise text as critical to the development of children’s

also described the characteristics of successful 9- thinking and the creation of quality writing

year-old writers. Earlier New Zealand research had (Fitzgerald, 1987; Graves, 1983; van Gelderen,

found that elementary school students rarely re- 1997). The ability to revise is significant because

vised their writing, and when they did it was to it helps the writer reflect and clarify his or her

change surface elements only (Flockton & Crooks, thinking with the goal of improving the writing

1999; Harold, 1984; Ward, 1991). The intention of (Calkins, 1991; Corden, 2001; Dix, 2003a;

the study was to determine to what extent young Fitzgerald, 1987, 1988; Graves, 1979, 1983;

writers revised. Could they “add, change, delete Murray, 1978). Fitzgerald’s (1988) definition was

and reorder the language to make sense, for gram- pivotal to this research. She maintained that revi-

mar and for impact?” (Ministry of Education, sion is an ongoing, recursive process where the

p. 35). writer’s

The research study was situated in three New

changes might affect meaning or they might merely

Zealand primary school classrooms, focusing on

fix features such as spelling. A writer may revise plans

fluent writers at years 5 and 6 (9- to 10-year-olds). for a composition before any words appear on paper,

Two different writing scenarios were observed in may change words or sentences while putting them on

each classroom. The first involved a poetic/creative paper, or may go back to make changes after a draft is

context and the other a transactional context. Data finished. (p. 124)

566 © 2006 International Reading Association (pp. 566–573) doi:10.1598/RT.59.6.6

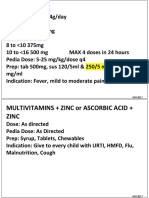

FIGURE 1

Revision practices

Revision changes

Surface changes Text-based changes

Formal Meaning preserving Microstructure Macrostructure

Additions Additions Additions

Deletions Deletions Deletions

Punctuation Substitutions Substitutions Substitutions

Spelling Reordering Restructuring Restructuring

Taxonomy definitions

Surface changes: These changes do not affect the meaning of the text.

a) Formal changes: These changes made to writing conventions include punctuation and spelling (and changes to

tense and word plurals).

b) Meaning-preserving changes: These changes paraphrase concepts in text but do not alter them (i.e., additions,

deletions, substitutions, reordering text). They can be single words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Text-based changes: These changes affect the meaning of the text.

a) Macrostructure changes: These major changes alter the summary of the completed text.

b) Microstructure changes: These changes alter the meaning of the text but do not affect the summary of the text.

Note. Adapted from Faigley and Witte (1981).

This definition recognizes that the revision process One of the major considerations for this re-

may be implemented as a range of subprocesses, search was to determine the extent to which stu-

including rewording, reordering, deleting, adding, dents could revise. This means at the whole-text

correcting, substituting, editing, and proofread- level implementing higher order thinking skills

ing—all skills that are intertwined with the com- such as making Text-based (meaning-altering)

posing process of writing. While some revision changes or making Surface changes like correct-

changes are unobservable, happening without the ing mechanical errors while preserving the mean-

pen even making marks on the paper, others are ev- ing of the words or sentences (Coe, 1986; Faigley

ident as overt thinking recorded in the written & Witte, 1981; Sommers, 1980). An adapted ver-

scripts (Fitzgerald, 1987; Graves, 1979, 1983; sion of Faigley and Witte’s taxonomy was used to

Hayes & Flower, 1986; Murray; Witte, 1985). analyze the writers’ revision practices, as identified

The understanding and implementation of re- in Figure 1.

vision practices provide many challenges for young

writers. Not only do they involve the complex cog-

nitive processes of planning, generating sentences, A snapshot of three young fluent

and matching the written text with the writer’s in-

tention (Hayes & Flower, 1986), but also they in- writers and their revision practice

volve the cognitive ability to reflect, compare, A key finding of this study identified that

evaluate, identify deficiencies, generate other pos- young writers, like expert writers (Faigley & Witte,

sibilities, and then revise, implementing possible 1981; Monro & Shin-ju, 2004), work in different

changes in the context of the writing purpose and ways. They draw on different literacy experiences

the reader audience (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1982; (Clay, 1998; Dyson, 1989). They create and build

Flower & Hayes, 1981; Graves, 1983; Parr, 1992). different texts in different ways (Dix, 2003b), and

I'll do it my way: Three writers and their revision practices 567

they construct their own understandings of writing as well as accuracy. Thus, many of Wiremu’s

and related revision practices according to interac- recorded Surface changes, evident as deletions in

tions with others and the task activities set (Barrs & his script, were initiated by higher order cognitive

Cork, 2001; Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1982; compositional changes made at the macro- and mi-

Calkins, 1991; Carruthers, Phillips, Rathgen, & crostructure level, given that they altered the mean-

Scanlen, 1991). ing of his text. For example, he explained,

In the following scenarios, three fluent writers

Well, one of the wizards conjured a flying fox to get in-

describe not only how they construct and revise

side. [I]nstead of writing Th [to begin the next sen-

their different texts in their own ways, but also they tence], I wrote Inside because I see sentences in my

demonstrate metacognitive awareness of revision head before I write them. I was going to say, “The army

practices they implemented, justifying reasons for of goblins and stuff were coming towards him,” but

making changes. then I thought they didn’t know that I was inside the

mansion, so I said, “Inside there was an army of goblins,

wolf-weres, vampires, and evil wizards and fighters

marched towards them.”

Wiremu

Wiremu is a fluent writer with a sound under- Wiremu was aware that final publication re-

standing of the writing process; he manipulates text quired him to attend to accuracy. He stated, “Well,

easily to suit his own purposes. Wiremu is able to I’m to look around for changes...like sentence

reflect on his writing behavior, talk about where his changing and beginnings, different beginnings...be-

ideas come from, and explain how he creates his fore I publish, spelling changes, punctuation, capi-

text, drawing on previous experiences from reading tal letters, and everything.” Although Wiremu

and video games. He writes at home as well as at expected to make revision changes, and in particu-

school and enjoys creating a range of texts, which lar proofreading corrections, as part of the confer-

includes keeping a diary, creating comic strips, and encing process with his teacher before publishing,

composing songs. he also made other changes while writing out the

final script. These were often meaning-preserving

Writing in a poetic context substitutions, such as changing thought to won-

The writing task in one class was to create a dered. He wrote in his final draft, “One of the three

picture book for young children. During prepara- good wizards did a spell and all of the monsters

tion the students read a range of picture books and froze,” but changed this during publication to “One

discussed the construction of narrative text. of the three good wizards froze all the very horri-

Wiremu’s writing behavior reflected a cognitive ble, ugly, vicious, blood sucking, ruthless, disgust-

process model (Flower & Hayes, 1981) as he ing monsters.” Of the 40 revision changes

worked in a recursive manner, composing, evalu- identified by Wiremu in his poetic text, 22 were

ating, and revising. He used the planning stage to Surface changes and 18 were Text-based meaning-

jot down, revise, and develop his thoughts. This altering changes.

was evident when he said, “The preplan, it just tells

me where I am in my characters, and it helps me Writing in a transactional context

think about what it’s going to be about.” Wiremu Wiremu’s transactional writing task was to con-

was unafraid to change direction midway in his struct a debate, giving reasons for and against a cho-

writing as he created new ideas and reflected on sen topic. His revision practice in this task followed

what he had already written. In this situation many a different process from his poetic writing because

of Wiremu’s revision changes were compositional, he wrote and revised according to a given frame-

attempting to match what was in his head with work. The framework provided a guide for plan-

what was written on paper. ning, composing, and revising a discussion in which

Wiremu’s revision practices in this context he listed the components of the genre and identifed

were meaning driven. Many internal cognitive the grammatical structure and language features of

changes (not evident in the written script) often ini- the text. Wiremu’s understanding of this writing

tiated further changes, which affected the meaning function was evident in the terminology he used.

568 The Reading Teacher Vol. 59, No. 6 March 2006

Although Wiremu still made cognitive, com- does not practise revision as just a proofreading

positional revision changes, these were confined procedure to be completed at the end of the draft

to minor alterations, and they focused on the pre- writing stage.

ciseness of language, correct punctuation, and

spelling. The framework provided by the teacher

guided Wiremu, resulting in few meaning-altering Anna

changes. Wiremu also used a writing checklist

Anna enjoys writing, especially when she se-

that the teacher handed out in class. This helped

lects her own topics. Usually she writes narratives

him to revise independently, focusing on the

about her own adventures. She often writes at home

genre, as well as checking for sense and the ac-

in her spare time. As she explained, “I’ve got this

curate use of writing conventions. Furthermore,

big pad...that’s like this humongous book that if I

the writers were expected to complete the check- feel like writing something in my free time, I just

list and then interact with a friend to get more get a pencil and just write on it ’cause its got like

ideas and to get help with the proofreading be- heaps of pages in it.”

fore going to the teacher. The teacher acted as the

gatekeeper who corrected final inaccuracies be-

fore publishing. Wiremu identified that he made

Writing in a poetic context

nine Surface changes and four Text-based mean- In one writing task, students had to select an

ing changes in the construction of his transac- experience from a school camp and present it in a

tional text. poetic form. Anna put considerable time into writ-

ing her poem. She worked from an outline and cre-

ated her first draft, second draft, and then final

Understanding composition and revision poem. She liked to construct her poem by rereading

Wiremu was aware that different purposes for and revising as she went, with the latter mostly in-

writing required different genres. He used appro- volving the addition of phrases. Anna explained her

priate terminology and talked easily about the com- thinking process when she talked about the word-

ponents of both narrative structure and writing a ing of her poem:

debate. He acknowledged the reader audience. This

was evident when he discussed the construction of Like I sort of go, I write a simple poem. I go to the first

his picture book, stating, “They’ve got to be quite sentence and make it a bit better, a bit better, a bit bet-

ter, until I’ve done what I want to do. Then, I go through

easy words and there may be repetition...because again just to check that it’s still good, and then keep go-

it’s going to be a children’s book.” ing down until I’ve got a really descriptive, good poem.

Wiremu expected to make changes to his writ-

ing. His draft book was set up so that he wrote on At this point, the changes were mostly cogni-

every second line “So that we can do fixing up lat- tive and meaning driven as Anna considered how to

er.” In practice, Wiremu actively revised, reworking build up poetic imagery. Anna explained how she

his text as he put his ideas into words. This, how- selected and reordered the lines of poetry, using

ever, was more evident in poetic writing where he ideas from a brainstorm and ticking them off as she

identified 40 revision changes. Wiremu continued transferred them to the draft poem. She said, “I put

to revise throughout all stages of the writing it in one place at one time, and then later I’d move

process, even as he published. He was metacogni- to another place, and another place until I’d been

tively aware of his revision practices—he recog- through all of that.”

nized that many of the changes he made with his Anna worked systematically and methodically

poetic writing were to manipulate, create, and re- through the writing stages, moving backward and

fine his ideas. However, the revision changes he forward through her text, continually shifting, re-

made to his transactional writing were in response ordering, and adding until she had built up her poet-

to meeting the criteria of the genre as well the de- ic image. She composed and revised by the cognitive

mands of accurate use of spelling and punctuation process model (Flower & Hayes, 1981), matching

conventions. Compared to the poetic writing func- written text with the ideas in her head; she spoke

tion, only 13 revision changes were made. Wiremu about creating visual images and selecting words

I'll do it my way: Three writers and their revision practices 569

to describe the pictures in her mind. She was of the changes were Text-based, meaning-changing

consciously aware of selecting and discarding words revisions. Of the 35 changes identified, 18 of these

as shown in the following extract from an interview: changed the meaning. For example, Anna recog-

nized the importance of diagrams. She said that she

Researcher: What’s happening in your head when

you’re playing around with words? What

added diagrams so “that if people don’t really un-

are you saying to yourself? derstand it, then they can just see the picture and

Anna: Probably, either like there are two.... I

understand what to do.” Anna revised sentences to

think there are two sort of, like, columns in make her instructions clearer for the reader. She ex-

my head, and if I don’t like it then I put it plained, “basically I made it a bit more precise in

in one column and I say, “I don’t like it” basically all of it, so that it’s just easier to read.”

and I just put it away—forget about it. These changes were especially evident in the sec-

Another idea, if I don’t like it, I put it away. ond draft as additions, substitutions, or deletions,

And then the ones I do like, I write them

and were a result of her editing partner trying the

down. So I think in my head first before I

write it down.

instructions. Of the total number of Surface

changes Anna made in her transactional writing

Anna revisited her poetic writing, making (17), half were made correcting capital letters.

changes that affected both the meaning and accura- Capital-letter corrections were seen as being im-

cy as described in the revision taxonomy. Most of portant for accuracy in sentence construction as

the changes were additions and substitutions at the well as for setting out each step in the procedural

microstructural level. She added in specific descrip- text structure. Surface changes were often imple-

tive phrases, often similes, that affected the meaning mented as part of the proofreading process. Anna

of the text and led to further Surface changes. stated, “I just do it at the end; I just read it through

These meaning-preserving changes included in case I missed anything. So if I did miss anything

adding, deleting, and substituting words or phrases, I can make it right.”

none of which affected the overall meaning of her Anna continued to make changes to the pres-

poem. The changes were part of Anna’s revision entation of the text. This stage of writing was im-

practice—as she enjoyed rearranging and playing portant and demanded creative thought and change.

with words. Further revision changes were influ- She explained, “I thought that instead of just hav-

enced by her editing partner and by teacher con- ing boxes, I could set it out in a leaf design.... I did

ferences, which helped her proofread and make try to make small trees...sort of 3D to catch peo-

final corrections. Anna identified 32 Surface ple’s eye.” Anna wanted to arrange the text and di-

changes and 14 Text-based, meaning-altering agrams so that it would appeal to the reader and

changes to her poetic text. have an effect. She identified 18 meaningful Text-

based changes.

Writing in a transactional context

In another class task, students had to write in- Understanding composition and revision

structions for making a paper tree. The students Anna was metacognitively aware of how she

were given a descriptive paragraph and asked to try constructed and revised her texts. She talked con-

to make the tree. From that experience they real- fidently about how she built up her text from basic

ized they had to go back and rewrite the instruc- sentence structures, rereading and revising as she

tions specifically and clearly so that a student in progressed. Anna was able to discuss her thinking

another class could follow them. The teacher dis- but at times didn’t have the metalanguage to sup-

played the key headings on a chart for students to port her thinking. Evidence that Anna “messed”

reference. with her writing was shown in both her poetic and

Anna made changes to her text throughout the transactional texts.

writing stages. Her script showed alterations on her Her scripts contained numerous insertions and

first draft and even more on the second draft. The deletions (in brackets). Of the 81 changes, Anna

final publication changed dramatically as she fo- made 46 changes to her poetic writing and 35

cused on the visual layout and presentation. Many changes in her transactional text. She revised

570 The Reading Teacher Vol. 59, No. 6 March 2006

poetic and transactional texts in different ways. Her Jon’s cognitive compositional decisions helped

poetic text she constructed from an outline, build- him create text. Once he had decided what to write,

ing the image by additions and substitutions. With he didn’t usually mess with the written script or

her transactional text, the changes resulted from a search for more interesting ideas. Jon made few

peer response indicating that her instructions were changes at the whole-text level. Any changes, usu-

not clear enough. She revisited and revised her ally deletions or spelling changes, were evident as

texts constantly, working to create a finished prod- formal or meaning-preserving changes. This was

uct that was pleasing to her. Her writing and revis- discussed in the second interview when Jon stated

ing were closely interwoven, as shown by her that he did not change any words or ideas, “’Cause

revisiting and reshaping the ideas. I thought it just sounded perfect and didn’t need any

Anna actively revised throughout the writing changes.” Jon’s written script showed little evidence

process, from when she first jotted down ideas to of messing with the written text at the Text-based

the creation of an interesting visual layout for the level. Only 1 of the 17 revision changes altered the

meaning of his poetic text. Generating and organ-

final publication. She was aware that revision

izing ideas were the major part of his thinking. The

changes involved two key processes and that it was

majority of overt surface changes were the result of

acceptable to rework large amounts of text, which

the writer’s desire to be accurate.

would ultimately involve Text-based changes, as

well as to correct the Surface features for accura-

Writing in a transactional context

cy. Furthermore, Anna exhibited control over the

revision process in her attempts to make her writ- Jon also had to write instructions explaining

ing more interesting. how to make a paper tree. Several factors influ-

enced his revision practice; these included a frame-

work demonstrating the structure of procedural

writing, a teacher conference, and a checklist given

Jon to him earlier. Jon explained, “The checklist, it just

Jon does little writing at home unless it is part tells what you should have done, and if you’ve

of his homework. In the classroom Jon works qui- done it, you tick yes, or no if you haven’t done it.”

etly and independently. He prefers writing tasks to However, the most influential change resulted from

be clearly set out so that he can write according to his partner carrying out the written instructions.

the teacher’s requirements. He regards his teacher This was done after the first draft. Jon explained,

as the expert: “At the start of the year the teacher I tested it out on a friend, and I just wrote, “Roll the

usually goes over what you have to do, and you just paper from the shortest end,” and they rolled it, and it

get taught what you have to do, and you know what was all loose. So I changed it to, “Tightly roll the paper

you have to do.” Jon takes pride in his finished from the shortest end.”

work and wants his writing to be accurate.

The addition of the word tightly changed the mean-

Writing in a poetic context ing of the sentence at the microstructural meaning

level. Jon also added another sentence, a step 4,

One of Jon’s writing tasks, like Anna’s, was to which gave more specific information about the

select a camp experience that he had enjoyed and instruction. He added to the script, which had read

write a poem. Self-questioning to generate and “Cut strips of newspaper but do not cut past 8 cm

clarify ideas was a feature of his writing construc- from the sellotaped end,” the words “Make the

tion, which helped him make decisions about re- strips about 1 cm wide.”

taining or discarding ideas. For example, he stated, During publishing, Jon made several Surface

Well, just say if the thing I was writing about was trees,

changes. These emphasized neatness and accura-

I just go, “What shall I write about? What color are the cy, in particular, his use of capital letters. He ex-

leaves? Or how many rings do they have to say how old plained, “It’s your neatest. There can’t be like

they are? And what shape they are, what shape differ- heaps of mistakes. There are a couple though,

ent types of trees are.” ’cause I was going to write a capital I instead of just

I'll do it my way: Three writers and their revision practices 571

a normal one.” Jon messed with this written script The writers reworked their texts continually

in a different way. He made few Text-based mean- throughout the interrelated stages of the writing

ing changes in the text; most of the changes (24 process, making cognitive decisions that were both

of the 29) were Surface changes. Jon also self- overt and covert in terms of what to change, and

corrected many of his spelling errors as he wrote. they were cognizant of genre demands.

These changes were evident throughout all stages The writers worked confidently, demonstrating

of the writing process. that they were metacognitively aware of their own

revision practices. They could explain and justify

Understanding composition and revision changes made at the Text-based and Surface levels.

Jon planned, composed, and revised most of The writers revised their poetic writing more

his text internally before writing it down, con- often. They appeared to have greater ownership

structing it in accordance with his perception of the and flexibility to make choices concerning lan-

task and the teacher’s expectations. Although Jon guage and sentence structure so that they could ex-

said that writing needed to make sense, his revision periment with words to create a desired image or

changes were mostly Surface changes that involved effect. However, when working with transactional

correcting spelling and punctuation. Jon’s under- text, revision changes were related to genre criteria,

standing of revision practice was strongly linked and the writers had less opportunity to take risks

to proofreading and editing practices. He perceived and explore language options.

revision as a procedure done at the end of writing, The writers in this study composed and revisit-

requiring the writer to “get it right.” In one instance ed their writing in quite different ways. Each writer

he said, “We read it through and make sure it demonstrated a different and personal way of con-

makes sense, and we correct any misspelled structing and revising text. Wiremu, who mostly

words.” Later he added, “You put any commas in, worked at the whole-text level, demonstrated that

full stops, and capital letters.” Jon’s understanding the composition and revision changes he made were

of revision was to read the finished draft, making integrated and implemented in an ongoing, recur-

sure it made sense and correcting Surface errors. sive manner, occurring throughout all the stages of

In both his poetic and transactional texts he writing, even when writing out the final published

made 46 changes. Of these, 40 were Surface script. In contrast, Anna revised and composed, bas-

changes; the other 6 were Text-based meaning ing her text on a skeleton framework and then

changes. When Jon revised, he often put parenthe- adding in and building up the ideas and images that

ses around letters or word errors. These deletions she desired. Her work was driven by a need to

and substitutions sometimes resulted from the text- match the written text with her intended text, and

composition process as he started to write some- she was content to play with words and construct a

thing and then changed his thinking; but most often particular image. Even though Jon shared the same

they resulted from spelling corrections noted as he teacher as Anna, he worked in quite a different way.

was writing. For example, he wrote, “Aim: To Most of his decisions were made at the planning

make a (p) magic tree following (thiese) these in- and organizational stage where he self-questioned

structions.” to generate and organize ideas. Having made these

compositional revisions, he saw no reason to make

major changes to the meaning of his text. Further

Students work differently revisions focused on accuracy.

The writers in this sample of students from the It was evident from this research study that stu-

study were active participants in the writing dents work differently when writing texts. Not only

process. They revisited and revised their writing, did they compose and revise texts in their own

altering it in a variety of ways. They demonstrated ways, but they also approached the construction of

an ability to continually revisit text according to poetic and transactional texts differently. The stu-

their purposes and in their own different and per- dents’ diverse ways of learning to write provides

sonal ways. another challenge for the classroom teacher.

572 The Reading Teacher Vol. 59, No. 6 March 2006

Dix teaches at the University of Waikato Flockton, L., & Crooks, T. (1999). Writing assessment results,

(School of Education, Private Bag 3105, 1998 (National Education Monitoring Report No. 12).

Dunedin, New Zealand: Educational Assessment

Hamilton, New Zealand). E-mail

Research Unit, University of Otago.

stephd@waikato.ac.nz. Flower, L., & Hayes, J. (1981). A cognitive process theory of

writing. College Composition and Communication, 32,

References 365–387.

Barrs, M., & Cork, V. (2001). The reader in the writer. Graves, D. (1979). What children show us about revision.

London: Centre for Language in Primary Education. Language Arts, 56, 312–319.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1982). From conversation Graves, D. (1983). Writing: Teachers and children at work.

to composition: The role of instruction in a developmen- London: Heinemann.

tal process. In R. Glaser (Ed.), Advances in Instructional Harold, B. (1984). Writing in school: Children’s revision of

Psychology (pp. 1–64). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. their written language. Unpublished master’s thesis,

Calkins, L. (1991). Living between the lines. Portsmouth, NH: University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Heinemann. Hayes, J., & Flower, L. (1986). Writing research and the

Carruthers, A., Phillips, P., Rathgen, E., & Scanlen, P. (1991). writer. American Psychologist, 41, 1106–1113.

The word process. Auckland, New Zealand: Longman Kress, G. (1999). Genre and the changing contexts for

Paul. English language arts. Language Arts, 76, 461–469.

Clay, M.M. (1998). By different paths to common outcomes. Ministry of Education. (1999). Report of the Literacy

York, ME: Stenhouse. Taskforce. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Coe, R.M. (1986). Teaching writing: The process approach, Monro, B., & Shin-ju, C.L. (2004, April). Development of writ-

humanism and the context of “crisis.” In S. de Castell, A. ing knowledge. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of

Luke, & K. Egan (Eds.), Literacy, society, and schooling: the American Educational Research Association, San

A reader (pp. 270–312). Cambridge, England: Cambridge Diego, CA.

Murray, D. (1978). Internal revision: A process of discovery.

University Press.

In C.R. Copper & L. Odell (Eds.), Research on composing

Corden, R. (2001). Research in progress: Teaching reading-

(pp. 85–103). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of

writing links. Reading, 35(1), 32–40.

English.

Dix, S. (2003a). Messing with writing: Children’s revision

Parr, J. (1992). Evaluation of the process of writing. SET:

practices. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of

The Best of Writing, New Zealand Council of Educational

Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Research, 13, 1–4.

Dix, S. (2003b). The warp and the weft of writing. Reading Sommers, N. (1980). Revision strategies of student writers

Forum New Zealand, 2, 5–13. and experienced adult writers. College Composition and

Dyer, D. (1992). The supportive classroom community. In Communication, 31, 378–388.

R.W. Ward (Ed.), Readings about writing (pp. 92–101). van Gelderen, A. (1997). Elementary students’ skills in revis-

Palmerston North, New Zealand: Dunmore Press. ing: Integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Dyson, A. (1989). Multiple worlds of child writers: Friends Written Communication, 14, 360–389.

learning to write. New York: Teachers College Press. Ward, R. (1991). Children’s writing: Revision as part of the

Faigley, L., & Witte, S. (1981). Analysing revisions. College drafting process. Unpublished manuscript, University of

Composition and Communication, 32, 400–414. Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Fitzgerald, J. (1987). Research on revision in writing. Review Witte, S. (1985). Revising, composing theory, and research

of Educational Research, 57, 481–506. design. In S.W. Freedman (Ed.), The aquisition of written

Fitzgerald, J. (1988). Helping young writers to revise: A brief language: Response and revision (pp. 250–284).

review for teachers. The Reading Teacher, 42, 124–129. Westport, CT: Ablex.

I'll do it my way: Three writers and their revision practices 573

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Irregular Verbs Family 1 TestsDocument6 paginiIrregular Verbs Family 1 TestsdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Count and Noncount Nouns Final TestDocument3 paginiCount and Noncount Nouns Final TestdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening and Speaking ActivitiesDocument41 paginiListening and Speaking Activitiesdaroksay50% (2)

- Americans With Disabilities Unit - Door To Door Movie QuestionsDocument2 paginiAmericans With Disabilities Unit - Door To Door Movie QuestionsdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capitalization and Punctuation QuizDocument3 paginiCapitalization and Punctuation QuizdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Characterization ActivityDocument2 paginiCharacterization ActivitydaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Capitalization and Punctuation Test2Document2 paginiCapitalization and Punctuation Test2daroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Half-Hour: Write The TimeDocument7 paginiHalf-Hour: Write The TimedaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Another Form: Innovative (Adjective) : (Noun) New Idea or Way of Doing SomethingDocument21 paginiAnother Form: Innovative (Adjective) : (Noun) New Idea or Way of Doing SomethingdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- "The Necklace" Original #1Document2 pagini"The Necklace" Original #1daroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Guide For "The Breadwinner"Document14 paginiStudy Guide For "The Breadwinner"daroksay100% (1)

- The Jigsaw Puzzle Literary TermsDocument2 paginiThe Jigsaw Puzzle Literary TermsdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test Side by Side Book One Chapters 9-10 A. Circle The Correct AnswerDocument3 paginiTest Side by Side Book One Chapters 9-10 A. Circle The Correct AnswerdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test 2Document2 paginiTest 2daroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Necklace Abridged #1Document2 paginiNecklace Abridged #1daroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plot OutlineDocument1 paginăPlot OutlinedaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journals 5Document1 paginăJournals 5daroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Run On SentencesDocument4 paginiRun On SentencesdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irregular Verbs Family 2 TestDocument6 paginiIrregular Verbs Family 2 TestdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irregular Verbs Family 1 TestsDocument6 paginiIrregular Verbs Family 1 TestsdaroksayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- MATH 7S eIIaDocument8 paginiMATH 7S eIIaELLA MAE DUBLASÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mohit Maru 4th Semester Internship ReportDocument11 paginiMohit Maru 4th Semester Internship ReportAdhish ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fruitful Outreaches Intercessory Prayer GuidelinesDocument5 paginiFruitful Outreaches Intercessory Prayer GuidelinesPaul Moiloa100% (1)

- The Old Man and The SeaDocument6 paginiThe Old Man and The Seahomeless_heartÎncă nu există evaluări

- End-To-End Lung Cancer Screening With Three-Dimensional Deep Learning On Low-Dose Chest Computed TomographyDocument25 paginiEnd-To-End Lung Cancer Screening With Three-Dimensional Deep Learning On Low-Dose Chest Computed TomographyLe Vu Ky NamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Securities and Exchange Commission: Non-Holding of Annual MeetingDocument2 paginiSecurities and Exchange Commission: Non-Holding of Annual MeetingBea AlonzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common RHU DrugsDocument56 paginiCommon RHU DrugsAlna Shelah IbañezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Diverticulosis PaperDocument12 paginiCase Study Diverticulosis Paperapi-381128376100% (3)

- 100 Commonly Asked Interview QuestionsDocument6 pagini100 Commonly Asked Interview QuestionsRaluca SanduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Document8 paginiMount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Matvat0100% (2)

- Why-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeDocument3 paginiWhy-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeBharat SahniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemistry Important Questions-2015-2016Document19 paginiChemistry Important Questions-2015-2016janu50% (4)

- Mod B - HSC EssayDocument11 paginiMod B - HSC EssayAryan GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Network Scanning TechniquesDocument17 paginiNetwork Scanning TechniquesjangdiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Qbasic (Algorithm) : By: Nischit P.N. Pradhan Class: 10'B To: Prakash PradhanDocument6 paginiOn Qbasic (Algorithm) : By: Nischit P.N. Pradhan Class: 10'B To: Prakash Pradhanapi-364271112Încă nu există evaluări

- Supply Chain Analytics For DummiesDocument69 paginiSupply Chain Analytics For DummiesUday Kiran100% (7)

- Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in The EndDocument15 paginiBeing Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in The EndEsteban0% (19)

- (Applied Logic Series 15) Didier Dubois, Henri Prade, Erich Peter Klement (Auth.), Didier Dubois, Henri Prade, Erich Peter Klement (Eds.) - Fuzzy Sets, Logics and Reasoning About Knowledge-Springer NeDocument420 pagini(Applied Logic Series 15) Didier Dubois, Henri Prade, Erich Peter Klement (Auth.), Didier Dubois, Henri Prade, Erich Peter Klement (Eds.) - Fuzzy Sets, Logics and Reasoning About Knowledge-Springer NeAdrian HagiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- IPA Digital Media Owners Survey Autumn 2010Document33 paginiIPA Digital Media Owners Survey Autumn 2010PaidContentUKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 3 Indigenous People in The PhilippinesDocument6 paginiQuiz 3 Indigenous People in The PhilippinesMa Mae NagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MInor To ContractsDocument28 paginiMInor To ContractsDakshita DubeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Document20 paginiCambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Balachandran PalaniandyÎncă nu există evaluări

- TreeAgePro 2013 ManualDocument588 paginiTreeAgePro 2013 ManualChristian CifuentesÎncă nu există evaluări

- UntitledDocument8 paginiUntitledMara GanalÎncă nu există evaluări

- ch09 (POM)Document35 paginich09 (POM)jayvee cahambingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard WrightDocument9 paginiFabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard Wrightfive4booksÎncă nu există evaluări

- EP105Use of English ArantxaReynosoDocument6 paginiEP105Use of English ArantxaReynosoArantxaSteffiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Domestic ViolenceDocument2 paginiDomestic ViolenceIsrar AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Interpretation and Application of Exoc Rine Panc Rea Tic Tes Ting in Small AnimalsDocument20 paginiPractical Interpretation and Application of Exoc Rine Panc Rea Tic Tes Ting in Small Animalsl.fernandagonzalez97Încă nu există evaluări

- Empirical Formula MgCl2Document3 paginiEmpirical Formula MgCl2yihengcyh100% (1)