Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Einsatzgruppen (German For "Task Forces"

Încărcat de

Zoth BernsteinTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Einsatzgruppen (German For "Task Forces"

Încărcat de

Zoth BernsteinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Einsatzgruppen (German for "task forces",[1] "deployment

groups";[2] singular Einsatzgruppe; official full name

Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD) were

Schutzstaffel (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi

Germany that were responsible for mass killings, primarily

by shooting, during World War II. The Einsatzgruppen were

involved in the murder of much of the intelligentsia and

cultural elite of Poland, and had an integral role in the

implementation of the Final Solution of the Jewish question

(Die Endlsung der Judenfrage) in territories conquered by

Nazi Germany. Almost all of the people they killed were

civilians, beginning with the intelligentsia and swiftly

progressing to Soviet political commissars, Jews, and

Gypsies throughout Eastern Europe.

Under the direction of Reichsfhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler

and the supervision of SS-Obergruppenfhrer Reinhard

Heydrich, the Einsatzgruppen operated in territories occupied

by the German armed forces following the invasion of Poland

in September 1939 and Operation Barbarossa (the invasion of

the Soviet Union) in June 1941. The Einsatzgruppen worked

hand-in-hand with the Orpo Police Battalions on the Eastern

Front to carry out operations ranging from the murder of a

few people to operations which lasted over two or more days,

such as the massacre at Babi Yar with 33,771 Jews killed in

two days, and the Rumbula massacre (with about 25,000

killed in two days of shooting). As ordered by Nazi leader

Adolf Hitler, the Wehrmacht cooperated with the

Einsatzgruppen and provided logistical support for their

operations. Historian Raul Hilberg estimates that between

1941 and 1945 the Einsatzgruppen and related auxiliary

troops killed more than two million people, including 1.3

million Jews. The total number of Jews murdered during the

Holocaust is estimated at 5.5 to 6 million people.

After the close of World War II, 24 senior leaders of the

Einsatzgruppen were prosecuted in the Einsatzgruppen Trial

in 194748, charged with crimes against humanity and war

crimes. Fourteen death sentences and two life sentences were

handed out. Four additional Einsatzgruppe leaders were later

tried and executed by other nations.

Einsatzgruppen

The Einsatzgruppen operated under the

administration of the Schutzstaffel (SS)

Killing of Jews at Ivanhorod, Ukraine, 1942. A

woman is attempting to protect a child with her own

body just before they are fired on with rifles at

close range.

Agency overview

Formed

Preceding

c. 1939

Einsatzkommando

agency

Jurisdiction

Nazi Germany

Occupied Europe

Headquarters RSHA, Prinz-Albrecht-Strae,

Berlin

523026N 132257E

Employees

~ 3,000 c. 1941

Minister

responsible

Heinrich Himmler,

Reichsfhrer-SS

Agency

executives

SS-Obergruppenfhrer

Reinhard Heydrich,

Director, RSHA

(19391942)

SS-Obergruppenfhrer Dr.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

2 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Ernst Kaltenbrunner,

Director, RSHA

(19431945)

1 Formation and Action T4

2 Invasion of Poland

3 Preparations for Operation Barbarossa

3.1 Organisation starting in 1941

4 Killings in the Soviet Union

4.1 Babi Yar

5 Killings in the Baltic states

5.1 Rumbula

6 Second Sweep

7 Transition to gassing

8 Plans for the Middle East and Britain

9 Jger Report

10 Involvement of the Wehrmacht

11 Einsatzgruppen Trial

12 See also

13 References

13.1 Citations

13.2 Books and journal articles

13.3 Online sources

14 Further reading

15 External links

Parent agency

Allgemeine SS and RSHA

The Einsatzgruppen were formed under the direction of SS-Obergruppenfhrer Reinhard Heydrich and

operated by the Schutzstaffel (SS) before and during World War II.[3] The Einsatzgruppen had its origins in the

ad hoc Einsatzkommando formed by Heydrich to secure government buildings and documents following the

Anschluss in Austria in March 1938.[4] Originally part of the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; SiPo), two

units of Einsatzgruppen were stationed in the Sudetenland in October 1938. When military action turned out not

to be necessary because of the Munich Agreement, the Einsatzgruppen were assigned to confiscate government

papers and police documents. They also secured government buildings, questioned senior civil servants, and

arrested as many as 10,000 Czech communists and German citizens.[5][4] From September 1939, the

Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office; RSHA) had overall command of the

Einsatzgruppen.[6]

As part of the drive to remove undesirable elements from the German population, from September to December

1939 the Einsatzgruppen and others took part in Action T4, a programme of systematic murder of the physically

and mentally handicapped and psychiatric hospital patients undertaken by the Nazi regime. Action T4 mainly

took place from 1939 to 1941, but continued until the end of the war. Initially the victims were shot by the

Einsatzgruppen and others, but gas chambers were put into use by spring 1940.[7]

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

3 of 18

In response to Fhrer und Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler's plan to invade

Poland, Heydrich re-formed the Einsatzgruppen to travel in the wake of

the German armies.[8] Membership at this point was drawn from the SS,

the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service; SD), and the police.[9] Heydrich

placed SS-Obergruppenfhrer Werner Best in command, who chose

leaders for the task forces and their subgroups, called

Einsatzkommandos, from among educated people with military

experience. Some had previously been members of paramilitary groups

such as the Freikorps.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Execution of Poles in Krnik, 20

October 1939

Numbering some 2,700 men at this point,[10] the Einsatzgruppen's

mission was the forceful de-politicisation of the Polish people and the elimination of groups most clearly

identified with Polish national identity: the intelligentsia, members of the clergy, teachers, and members of the

nobility.[9][11] As stated by Hitler: "... there must be no Polish leaders; where Polish leaders exist they must be

killed, however harsh that sounds".[12] The Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen lists of people to be killed had

been drawn up by the SS as early as May 1939.[9] The Einsatzgruppen performed these murders with the

support of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, a paramilitary group consisting of ethnic Germans living in

Poland.[13] Members of the SS, the Wehrmacht, and the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police; Orpo) also shot

civilians during the Polish campaign.[14] Approximately 65,000 civilians were killed by the end of 1939. In

addition to leaders of Polish society, they killed Jews, prostitutes, Romani people, and the mentally ill.

Psychiatric patients in Poland were initially killed by shooting, but by spring 1941 gas vans were widely

used.[15][16]

Seven Einsatzgruppen of battalion strength operated in Poland. Each was subdivided into four

Einsatzkommandos of company strength.[17]

Einsatzgruppe I, commanded by SS-Standartenfhrer Bruno Streckenbach, acted with 14th Army

Einsatzgruppe II, SS-Obersturmbannfhrer Emanuel Schfer, acted with 10th Army

Einsatzgruppe III, SS-Obersturmbannfhrer und Regierungsrat Dr. Herbert Fischer, acted with 8th Army

Einsatzgruppe IV, SS-Brigadefhrer Lothar Beutel, acted with 4th Army

Einsatzgruppe V, SS-Standartenfrer Ernst Damzog, acted with 3rd Army

Einsatzgruppe VI, SS-Oberfhrer Erich Naumann, acted in Wielkopolska

Einsatzgruppe VII, SS-Obergruppenfhrer Udo von Woyrsch and SS-Gruppenfhrer Otto Rasch, acted in

Upper Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia[17]

Though they were formally under the command of the army, the Einsatzgruppen received their orders directly

from Heydrich and for the most part acted independently of the army.[18][19] Many senior army officers were

only too glad to leave these genocidal actions to the task forces, as the killings violated the rules of warfare as

set down in the Geneva Conventions. However, Hitler had decreed that the army would have to tolerate and

even offer logistical support to the Einsatzgruppen when it was tactically possible to do so. Some army

commanders complained about unauthorised shootings, looting, and rapes committed by members of the

Einsatzgruppen and the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, to little effect.[20] For example, when Generaloberst

Johannes Blaskowitz sent a memorandum of complaint to Hitler about the atrocities, Hitler dismissed his

concerns as "childish", and Blaskowitz was relieved of his post in May 1940. He continued to serve in the army

but never received promotion to field marshal.[21]

The final task of the Einsatzgruppen in Poland was to round up the remaining Jews and concentrate them in

ghettos within major cities with good railway connections. The intention was to eventually remove all the Jews

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

4 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

from Poland, but at this point their final destination had not yet been determined.[22][23] Together, the

Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen also drove tens of thousands of Jews eastward into Soviet-controlled

territory.[14]

On 13 March 1941, in the lead-up to Operation Barbarossa, the planned invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler

dictated his "Guidelines in Special Spheres re: Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa)". Sub-paragraph B

specified that Reichsfhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler would be given "special tasks" on direct orders from the

Fhrer, which he would carry out independently.[24] This directive was intended to prevent friction between the

Wehrmacht and the SS in the upcoming offensive.[24] Hitler also specified that criminal acts against civilians

perpetrated by members of the Wehrmacht during the upcoming campaign would not be prosecuted in the

military courts, and thus would go unpunished.[25]

In a speech to his leading generals on 30 March 1941, Hitler described his envisioned war against the Soviet

Union. General Franz Halder, the Army's Chief of Staff, described the speech:

Struggle between two ideologies. Scathing evaluation of Bolshevism, equals antisocial criminality.

Communism immense future danger ... This a fight to the finish. If we do not accept this, we shall

beat the enemy, but in thirty years we shall again confront the Communist foe. We don't make war

to preserve the enemy ... Struggle against Russia: Extermination of Bolshevik Commissars and of

the Communist intelligentsia ... Commissars and GPU personnel are criminals and must be treated

as such. The struggle will differ from that in the west. In the east harshness now means mildness for

the future.[26]

Though General Halder did not record any mention of Jews, German historian Andreas Hillgruber argued that

because of Hitler's frequent contemporary statements about the coming war of annihilation against "JudeoBolshevism", his generals would have understood Hitler's call for the destruction of the Soviet Union as also

comprising a call for the destruction of its Jewish population.[26] The genocide was often described using

euphemisms such as "special tasks" and "executive measures"; Einsatzgruppe victims were often described as

having been shot while trying to escape.[27] In May 1941 Heydrich verbally passed on the order to kill the

Soviet Jews to the SiPo NCO School in Pretzsch, where the commanders of the reorganised Einsatzgruppen

were being trained for Operation Barbarossa.[28] In spring 1941, Heydrich and the First Quartermaster of the

Wehrmacht Heer, General Eduard Wagner, successfully completed negotiations for co-operation between the

Einsatzgruppen and the German Army to allow the implementation of the "special tasks".[29] Following the

Heydrich-Wagner agreement on 28 April 1941, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch ordered that when

Operation Barbarossa began, all German Army commanders were to immediately identify and register all Jews

in occupied areas in the Soviet Union, and fully co-operate with the Einsatzgruppen.[30]

In further meetings held in June 1941 Himmler outlined to top SS leaders the regime's intention to reduce the

population of the Soviet Union by 30 million people, not only through direct killing of those considered racially

inferior, but by depriving the remainder of food and other necessities of life.[31]

Organisation starting in 1941

For Operation Barbarossa, initially four Einsatzgruppen were created, each numbering 500990 men to

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

5 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

comprise a total force of 3,000.[32] Einsatzgruppen A, B, and C were to be attached to Army Groups North,

Centre, and South; Einsatzgruppe D was assigned to the 11th Army. The Einsatzgruppe for Special Purposes

operated in eastern Poland starting in July 1941.[32] The Einsatzgruppen were under the control of the RSHA,

headed by Heydrich and later by his successor, SS-Obergruppenfhrer Ernst Kaltenbrunner. Heydrich gave

them a mandate to secure the offices and papers of the Soviet state and Communist Party; to liquidate all the

higher cadres of the Soviet state; and to instigate and encourage pogroms against Jewish populations.[33] The

men of the Einsatzgruppen were recruited from the SD, Gestapo, Kriminalpolizei (Kripo), Orpo, and WaffenSS.[32] Each Einsatzgruppe was under the operational control of the Higher SS Police Chiefs in its area of

operations.[30] In May 1941 General Wagner and SS-Brigadefhrer Walter Schellenberg agreed that the

Einsatzgruppen in front-line areas were to operate under army command, while the army provided the

Einsatzgruppen with all necessary logistical support.[34]

Heydrich acted under orders from Reichsfhrer-SS Himmler, who supplied

security forces on an "as needed" basis to the local SS and Police Leaders.[3]

Led by SD, Gestapo, and Kripo officers, Einsatzgruppen included recruits from

the Orpo, Security Service and Waffen-SS, augmented by uniformed volunteers

from the local auxiliary police force.[35] Each Einsatzgruppe was supplemented

with a reserve battalion of Orpos and Waffen-SS as well as support personnel

such as drivers and radio operators.[32] On average, the Orpo formations were

larger and better armed, with heavy machine-gun detachments, which enabled

them to carry out operations beyond the capability of the SS.[35] Each death

squad followed an assigned army group as they advanced into the Soviet

Union.[36] During the course of their operations, the Einsatzgruppen

commanders received assistance from the Wehrmacht.[36] Activities ranged from

Otto Rasch photographed by

the murder of targeted groups of individuals named on carefully prepared lists,

Allied forces at the

to joint city-wide operations with SS Einsatzgruppen which lasted for two or

more days, such as the massacres at Babi Yar, perpetrated by the Orpo Reserve

Nuremberg Trials, circa

Battalion 45, and at Rumbula, by Battalion 22, reinforced by local

1948

[37][38]

Schutzmannschaften (auxiliary police).

The SS brigades, wrote historian

Christopher Browning, were "only the thin cutting edge of German units that became involved in political and

racial mass murder."[39]

Many Einsatzgruppe leaders were highly educated; for example, nine of seventeen leaders of Einsatzgruppe A

held doctorate degrees.[40] Three Einsatzgruppen were commanded by holders of doctorates, one of whom

(SS-Gruppenfhrer Otto Rasch) held a double doctorate.[41]

Additional Einsatzgruppen were created as additional territory was conquered. Einsatzgruppe E operated in

Independent State of Croatia under three commanders, SS-Obersturmbannfhrer Ludwig Teichmann,

SS-Standartenfhrer Gnther Herrmann, and lastly SS-Standartenfhrer Wilhelm Fuchs. The unit was

subdivided into five Einsatzkommandos located in Vinkovci, Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Knin, and Zagreb.[42][43]

Einsatzgruppe F worked with Army Group South.[43] Einsatzgruppe G operated in Romania, Hungary, and

Ukraine, commanded by SS-Standartenfhrer Dr. Josef Kreuzer.[42] Einsatzgruppe H was assigned to

Slovakia.[44] Einsatzgruppen K and L, under SS-Oberfhrer Dr. Emanuel Schfer and SS-Standartenfhrer Dr.

Ludwig Hahn, worked alongside 5th and 6th Panzer Armies during the Ardennes offensive.[45] Hahn had

previously been in command of Einsatzgruppe Griechenland in Greece.[46]

Other Einsatzgruppen and Einsatzkommandos included Einsatzgruppe Iltis (operated in Carinthia, on the border

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

6 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

between Slovenia and Austria) under SS-Standartenfhrer Paul Blobel,[47] Einsatzgruppe Jugoslawien

(Yugoslavia)[48] Einsatzkommando Luxemburg (Luxembourg),[43] Einsatzgruppe Norwegen (Norway)

commanded by SS-Oberfhrer Dr. Franz Walter Stahlecker,[49] Einsatzgruppe Serbien (Yugoslavia) under

SS-Standartenfhrer Wilhelm Fuchs and SS-Gruppenfhrer August Meysner,[50] Einsatzkommando Tilsit

(Lithuania, Poland),[51] and Einsatzgruppe Tunis (Tunis), commanded by SS-Obersturmbannfhrer Walter

Rauff.[52]

After the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Einsatzgruppen's main assignment was to kill

civilians, as in Poland, but this time its targets specifically included Soviet Communist Party commissars and

Jews.[33] In a letter dated 2 July 1941 Heydrich communicated to his SS and Police Leaders that the

Einsatzgruppen were to execute all senior and middle ranking Comintern officials; all senior and middle

ranking members of the central, provincial, and district committees of the Communist Party; extremist and

radical Communist Party members; people's commissars; and Jews in party and government posts. Open-ended

instructions were given to execute "other radical elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins,

agitators, etc.)." He instructed that any pogroms spontaneously initiated by the occupants of the conquered

territories were to be quietly encouraged.[53]

On 8 July, Heydrich announced that all Jews were to be regarded as partisans, and gave the order for all male

Jews between the ages of 15 and 45 to be shot.[54] On 17 July Heydrich ordered that the Einsatzgruppen were to

kill all Jewish Red Army prisoners of war, plus all Red Army prisoners of war from Georgia and Central Asia,

as they too might be Jews.[55] Unlike in Germany, where the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 defined as Jewish

anyone with at least three Jewish grandparents, the Einsatzgruppen defined as Jewish anyone with at least one

Jewish grandparent; in either case, whether or not the person practised the religion was irrelevant.[56] The unit

was also assigned to exterminate Romani people and the mentally ill. It was common practice for the

Einsatzgruppen to shoot hostages.[57]

As the invasion began, the Germans pursued the fleeing Red Army,

leaving a security vacuum. Reports surfaced of Soviet guerrilla activity

in the area, with local Jews immediately suspected of collaboration.

Heydrich ordered his officers to incite anti-Jewish pogroms in the newly

occupied territories.[58] Pogroms, some of which were orchestrated by

the Einsatzgruppen, broke out in Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine.[59]

Within the first few weeks of Operation Barbarossa, 40 pogroms led to

the deaths of 10,000 Jews, and by the end of 1941 some 60 pogroms had

A teenage boy stands beside his

taken place, claiming as many as 24,000 victims.[59][60] However,

murdered family shortly before his

SS-Brigadefhrer Franz Walter Stahlecker, commander of

own death by the SS. Zboriv,

Einstazgruppe A, reported to his superiors in mid-October that the

Ukraine, 5 July 1941

residents of Kaunas were not spontaneously starting pogroms, and secret

assistance by the Germans was required.[61] A similar reticence was

noted by Einsatzgruppe B in Russia and Belarus and Einsatzgruppe C in Ukraine; the further east the

Einsatzgruppen travelled, the less likely the residents were to be prompted into killing their Jewish

neighbours.[62]

All four main Einsatzgruppen took part in mass shootings from the early days of the war.[63] Initially the targets

were adult Jewish men, but by August the net had been widened to include women, children, and the

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

7 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

elderlythe entire Jewish population. Initially there was a semblance of legality given to the shootings, with

trumped-up charges being read out (arson, sabotage, black marketeering, or refusal to work, for example) and

victims being killed by a firing squad. As this method proved too slow, the Einsatzkommandos began to take

their victims out in larger groups and shot them next to, or even inside, mass graves that had been prepared.

Some Einsatzkommandos started to use automatic weapons, with survivors being killed with a pistol shot.[64]

As word of the massacres got out, many Jews fled; in Ukraine, 70 to 90 per cent of the Jews ran away. This was

seen by the leader of Einsatzkommando VI as beneficial, as it would save the regime the costs of deporting the

victims further east over the Urals.[65] In other areas the invasion was so successful that the Einsatzgruppen had

insufficient forces to immediately kill all the Jews in the conquered territories.[66] A situation report from

Einsatzgruppe C in September 1941 noted that not all Jews were members of the Bolshevist apparatus, and

suggested that the total elimination of Jewry would have a negative impact on the economy and the food supply.

The Nazis began to round their victims up into concentration camps and ghettos and rural districts were for the

most part rendered Judenfrei (free of Jews).[67] Jewish councils were set up in major cities and forced labour

gangs were established to make use of the Jews as slave labour until they were totally eliminated, a goal that

was postponed until 1942.[68]

Einsatzgruppen used public hangings as a terror tactic on the local population. An Einsatzgruppe B report, dated

9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity near Demidov, all male

residents aged 15 to 55 were put in a camp to be screened. The screening produced seventeen people identified

as "partisans" and "Communists". Five members of the group were hanged while 400 local residents were

assembled to watch; the rest were shot.[69]

Babi Yar

The largest mass shooting perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen took place on 29 and 30 September 1941 at Babi

Yar, a ravine northwest of Kiev, a city in Ukraine that had fallen to the Germans on 19 September.[70][71] The

perpetrators included a company of Waffen-SS attached to Einsatzgruppe C under Rasch, members of

Sonderkommando 4a under SS-Obergruppenfhrer Friedrich Jeckeln, and some Ukrainian auxiliary police.[72]

The Jews of Kiev were told to report to a certain street corner on 29 September; anyone who disobeyed would

be shot. Since word of massacres in other areas had not yet reached Kiev and the assembly point was near the

train station, they assumed they were being deported. People showed up at the rendezvous point in large

numbers, laden with possessions and food for the journey.[73]

After being marched two miles north-west of the city centre, the victims encountered a barbed wire barrier and

numerous Ukrainian police and German troops. Thirty or forty people at a time were told to leave their

possessions and were escorted through a narrow passageway lined with soldiers brandishing clubs. Anyone who

tried to escape was beaten. Soon the victims reached an open area, where they were forced to strip, and then

were herded down into the ravine. People were forced to lie down in rows on top of the bodies of other victims,

and they were shot in the back of the head or the neck by members of the execution squads.[74]

The murders continued for two days, claiming a total of 33,771 victims.[71] Sand was shovelled and bulldozed

over the bodies and the sides of the ravine were dynamited to bring down more material.[75] Anton Heidborn, a

member of Sonderkommando 4a, later testified that three days later that there were still people alive among the

corpses. Heidborn spent the next few days helping smooth out the "millions" of banknotes taken from the

victims' possessions.[76] The clothing was taken away, destined to be re-used by German citizens.[75] Jeckeln's

troops shot more than 100,000 Jews by the end of October.[71]

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

8 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppe A operated in the formerly Soviet-occupied Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

According to its own reports to Himmler, Einsatzgruppe A killed almost 140,000 people in the five months

following the invasion: 136,421 Jews, 1,064 Communists, 653 people with mental illnesses, 56 partisans, 44

Poles, five Gypsies, and one Armenian were reported killed between 22 June and 25 November 1941.[77]

Upon entering Kaunas, Lithuania, on 25 June 1941, the Einsatzgruppe released the criminals from the local jail

and encouraged them to join the pogrom which was underway.[78] Between 2327 June 1941, 4,000 Jews were

killed on the streets of Kaunas and in nearby open pits and ditches.[79] Particularly active in the Kaunas pogrom

was the so-called "Death Dealer of Kaunas", a young man who murdered Jews with a crowbar at the Lietukis

Garage before a large crowd that cheered each killing with much applause; he occasionally paused to play the

Lithuanian national anthem "Tautika giesm" on his accordion before resuming the killings.[79][80]

As Einsatzgruppe A advanced into Lithuania, it actively recruited local nationalists and antisemitic groups. In

July 1941, members of the Baltaraisciai movement joined the massacres.[60] A pogrom in Riga in early July

killed 400 Jews. Latvian nationalist Viktors Arjs and his supporters undertook a campaign of arson against

synagogues.[81] On 2 July, Einsatzgruppe A commander Stahlecker appointed Arjs to head the Arajs

Kommando,[60] a Sonderkommando of about 300 men, mostly university students. Together, Einsatzgruppe A

and the Arjs Kommando killed 2,300 Jews in Riga on 67 July.[81] Within six months, Arjs and his men

would kill about half of Latvia's Jewish population.[82]

Local officials, the Selbstschutz, and the Hilfspolizei (Auxiliary Police) played a key role in rounding up and

massacring Jewish Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians.[83] These groups helped the Einsatzgruppen and other

killing units to quickly identify Jews.[83] The Hilfspolizei, consisting of auxiliary police organised by the

Germans and recruited from former Latvian Army and police officers, ex-Aizsargi, members of the

Prkonkrusts, and university students, assisted in the murder of Latvia's Jewish citizens.[82] Similar units were

created elsewhere, and provided much of the manpower for the Holocaust in Eastern Europe.[84]

With the creation of units such as the Arjs Kommando, the Rollkommando Hamann in Lithuania, and the

Omakaitse militia in Estonia,[85] the attacks changed from the spontaneous mob violence of the pogroms to

more systematic massacres.[82] With extensive local help, Einsatzgruppe A was the first Einsatzgruppe to

attempt to systematically exterminate all the Jews in its area.[86][83] Latvian historian Modris Eksteins wrote:

Of the roughly 83,000 Jews who fell into German hands in Latvia, not more than 900 survived; and

of the more than 20,000 Western Jews sent into Latvia, only some 800 lived through the

deportation until liberation. This was the highest percentage of eradication in all of Europe.[87]

In late 1941, the Einsatzkommandos settled into headquarters in Kovno, Riga, and Tallinn. Einsatzgruppe A

grew less mobile and faced problems because of its small size. The Germans relied increasingly on the Arjs

Kommando and similar groups to perform massacres of Jews.[85]

Such extensive and enthusiastic collaboration with the Einsatzgruppen has been attributed to several factors.

Since the Russian Revolution of 1905, the Kresy Wschodnie and other borderlands had experienced a political

culture of violence.[88] The period of Soviet rule had been profoundly traumatic for residents of the Baltic states

and areas that had been part of Poland until 1939; the population was brutalised and terrorised by the imposed

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

9 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Soviet rule, and the existing familiar structures of society were destroyed.[89]

Historian Erich Haberer notes that many survived and made sense of the "totalitarian atomization" of society by

seeking conformity with communism.[90] As a result, by the time of the German invasion in 1941, many had

come to see conformity with a totalitarian regime as socially acceptable behaviour; thus, people simply

transferred their allegiance to the German regime when it arrived.[90] Some who had collaborated with the

Soviet regime sought to divert attention from themselves by naming Jews as collaborators and killing them.[91]

Rumbula

In November 1941 Himmler was dissatisfied with the pace of the exterminations in Latvia, as he intended to

move Jews from Germany into the area. He assigned SS-Obergruppenfhrer Jeckeln, one of the perpetrators of

the Babi Yar massacre, to liquidate the Riga ghetto. Jeckeln selected a site about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi)

southeast of Riga near the Rumbula railway station, and had 300 Russian prisoners of war prepare the site by

digging pits in which to bury the victims. Jeckeln organised around 1,700 men, including 300 members of the

Arajs Kommando, 50 German SD men, and 50 Latvian guards, most of whom had already participated in mass

killings of civilians. These troops were supplemented by Latvians, including members of the Riga city police,

battalion police, and ghetto guards. Around 1,500 able-bodied Jews would be spared execution so their slave

labour could be exploited; a thousand men were relocated to a fenced-off area within the ghetto and 500 women

were temporarily housed in a prison and later moved to a separate nearby ghetto, where they were put to work

mending uniforms.[92]

Although Rumbula was on the rail line, Jeckeln decided that the victims should travel on foot from Riga to the

execution ground. Trucks and buses were arranged to carry children and the elderly. The victims were told that

they were being relocated, and were advised to bring up to 20 kilograms (44 lb) of possessions. The first day of

executions, 30 November 1941, began with the perpetrators rousing and assembling the victims at 4:00 am. The

victims were moved in columns of a thousand people toward the execution ground. As they walked, some SS

men went up and down the line, shooting people who could not keep up the pace or who tried to run away or

rest.[93]

When the columns neared the prepared execution site, the victims were driven some 270 metres (300 yd) from

the road into the forest, where any possessions that had not yet been abandoned were seized. Here the victims

were split into groups of fifty and taken deeper into the forest, near the pits, where they were ordered to strip.

The victims were driven into the prepared trenches, made to lie down, and shot in the head or the back of the

neck by members of Jeckeln's bodyguard. Around 13,000 Jews from Riga were killed at the pits that day, along

with a thousand Jews from Berlin who had just arrived by train. On the second day of the operation, 8

December 1941, the remaining 10,000 Jews of Riga were killed in the same way. About a thousand were killed

on the streets of the city or on the way to the site, bringing the total deaths for the two-day extermination to

25,000 people. For his part in organising the massacre, Jeckeln was promoted to Leader of the SS Upper

Section, Ostland.[94]

Einsatzgruppe B, C, and D did not immediately follow Einsatzgruppe A's example in systematically killing all

Jews in their areas. The Einsatzgruppe commanders, with the exception of Einsatzgruppe A's Stahlecker, were

of the opinion by the fall of 1941 that it was impossible to kill the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union

in one sweep, and thought the killings should stop.[95] An Einsatzgruppe report dated 17 September advised

that the Germans would be better off using any skilled Jews as labourers rather than shooting them.[95] Also, in

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

10 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

some areas poor weather and a lack of transportation led to a slowdown in deportations of Jews from points

further west.[96] Thus, an interval passed between the first round of Einsatzgruppen massacres in summer and

fall, and what American historian Raul Hilberg called the second sweep, which started in December 1941 and

lasted into the summer of 1942.[97] During the interval, the surviving Jews were forced into ghettos.[98]

Einsatzgruppe A had already murdered almost all Jews in its area, so it shifted its operations into Belarus to

assist Einsatzgruppe B. In Dnepropetrovsk in February 1942, Einsatzgruppe D reduced the city's Jewish

population from 30,000 to 702 over the course of four days.[99] The German Order Police and local

collaborators provided the extra manpower needed to perform all the shootings. Haberer wrote that, as in the

Baltic states, the Germans could not have killed so many Jews so quickly without local help. He points out that

the ratio of Order Police to auxiliaries was 1 to 10 in both Ukraine and Belarus. In rural areas the proportion

was 1 to 20. This meant that most Ukrainian and Belarusian Jews were killed by fellow Ukrainians and

Belarusians commanded by German officers rather than by Germans.[100]

The second wave of exterminations in the Soviet Union met with armed resistance in some areas, though the

chance of success was poor. Weapons were typically primitive or home-made. Communications were

impossible between ghettos in various cities, so there was no way to create a unified strategy. Few in the ghetto

leadership supported resistance for fear of reprisals on the ghetto residents. Mass break-outs were sometimes

attempted, though survival in the forest was nearly impossible due to the lack of food and the fact that escapees

were often tracked down and killed.[101]

After a time, Himmler found that the killing methods used by the

Einsatzgruppen were inefficient: they were costly, demoralising for the

troops, and sometimes did not kill the victims quickly enough.[102]

Many of the troops found the massacres to be difficult if not impossible

to perform. Some of the perpetrators suffered physical and mental health

problems, and many turned to drink.[103] As much as possible, the

Einsatzgruppen leaders militarized the genocide. The historian Christian

Ingrao notes an attempt was made to make the shootings a collective act

without individual responsibility. Framing the shootings in this way was

Nazi gas van used to murder people

not psychologically sufficient for every perpetrator to feel absolved of

at Chemno extermination camp

guilt.[104] Browning notes three categories of potential perpetrators:

those who were eager to participate right from the start, those who

participated in spite of moral qualms because they were ordered to do so, and a significant minority who refused

to take part.[105] A few men spontaneously became excessively brutal in their killing methods and their zeal for

the task. Commander of Einsatzgruppe D, SS-Gruppenfhrer Otto Ohlendorf, particularly noted this propensity

towards excess, and ordered that any man who was too eager to participate or too brutal should not perform any

further executions.[106]

During a visit to Minsk in August 1941, Himmler witnessed an Einsatzgruppen mass execution first-hand and

concluded that shooting Jews was too stressful for his men.[107] By November he made arrangements for any

SS men suffering ill health from having participated in executions to be provided with rest and mental health

care.[108] He also decided a transition should be made to gassing the victims, especially the women and

children, and ordered the recruitment of expendable native auxiliaries who could assist with the murders.

[108][109] Gas vans, which had been used previously to kill mental patients, began to see service by all four main

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

11 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen from 1942.[110] However, the gas vans were not popular with the Einsatzkommandos, because

removing the dead bodies from the van and burying them was a horrible ordeal. Prisoners or auxiliaries were

often assigned to do this task so as to spare the SS men the trauma.[111] Some of the early mass killings at

extermination camps used carbon monoxide fumes produced by diesel engines, similar to the method used in

gas vans, but by as early as September 1941 experiments were begun at Auschwitz using Zyklon B, a

cyanide-based pesticide gas.[112]

Plans for the total eradication of the Jewish population of Europeeleven million peoplewere formalised at

the Wannsee Conference, held on 20 January 1942. Some would be worked to death, and the rest would be

killed in the implementation of the Final Solution of the Jewish question (German: Die Endlsung der

Judenfrage).[113] Permanent killing centres at Auschwitz, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and other Nazi

extermination camps replaced mobile death squads as the primary method of mass killing.[114] The

Einsatzgruppen remained active, however, and were put to work fighting partisans, particularly in Belarus.[115]

After the fall of Stalingrad in February 1943, Himmler realised that Germany would likely lose the war, and

ordered the formation of a special task force, Sonderkommando 1005, under SS-Standartenfhrer Paul Blobel.

The unit's assignment was to visit mass graves all along the Eastern Front to exhume bodies and burn them in

an attempt to cover up the genocide. The task remained unfinished at the end of the war, and many mass graves

remain unmarked and unexcavated.[116]

By 1944 the Red Army had begun to push the German forces out of Eastern Europe, and the Einsatzgruppen

retreated alongside the Wehrmacht. By late 1944, most Einsatzgruppen personnel had been folded into

Waffen-SS combat units or transferred to permanent death camps. Hilberg estimates that between 1941 and

1945 the Einsatzgruppen and related agencies killed more than two million people, including 1.3 million

Jews.[117] The total number of Jews murdered during the war is estimated at 5.5 to six million people.[118]

According to research by German historians Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Martin Cppers, an Einsatzgruppe

was created in 1942 to kill the half-million Jews living in the British Mandate of Palestine and the 50,000 Jews

of Egypt. Einsatzgruppe Egypt, standing by in Athens, was prepared to go to Palestine once German forces

arrived there.[52] SS-Obersturmbannfhrer Walter Rauff was to lead the unit.[119] Given its small staff of only

24 men, Einsatzgruppe Egypt would have needed help from local residents and from the Afrika Korps to

complete their assignment. Its members planned to enlist collaborators from the local population to perform the

killings under German leadership. [120] Former Iraqi prime minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani and the Grand Mufti

of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini played roles, engaging in antisemitic radio propaganda, preparing to recruit

volunteers, and in raising an Arab-German Battalion that would also follow Einsatzgruppe Egypt to the Middle

East.[121] Commander of the Afrika Korps Field Marshal Erwin Rommel promised the co-operation of his corps

in these assignments.[122] In an agreement signed in July 1942 between the two groups, Rommel promised

logistical support for Einsatzgruppe Egypt, which was to serve under command of the Wehrmacht.[123] The

group never left Greece, however; the plans were set aside after the Allied victory at the Battle of El

Alamein.[124]

Had Operation Sea Lion, the German plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom been launched, six

Einsatzgruppen were scheduled to follow the invasion force into Britain. They were provided with a list called

die Sonderfahndungsliste, G.B. ("Special Search List, G.B"), known as The Black Book after the war, of 2,300

people to be immediately imprisoned by the Gestapo. The list included Churchill, members of the cabinet,

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

12 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

prominent journalists and authors, and members of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile.[125]

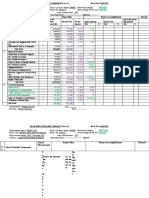

The Einsatzgruppen kept official records of many of their massacres and

provided detailed reports to their superiors. The Jger Report, filed by

Commander SS-Standartenfhrer Karl Jger on 1 December 1941 to his

superior, Stahlecker (head of Einsatzgruppe A), covers the activities of

Einsatzkommando III in Lithuania over the five-month period from 2

July 1941 to 25 November 1941.[126]

Jger's report provides an almost daily running total of the liquidations

of 137,346 people, the vast majority of them Jews.[126] The report

documents the exact date and place of massacres, the number of victims,

and their breakdown into categories (Jews, Communists, criminals, and

so on).[127] Women were shot from the very beginning, but initially in

fewer numbers than men.[128] Children were first included in the tally

starting in mid-August, when 3,207 people were murdered in Rokikis

on 1516 August 1941.[127] For the most part the report does not give

any military justification for the killings; people were killed solely

Page 6 of the Jger Report shows the

because they were Jews.[127] In total, the report lists over 100 executions

number of people killed by

in 71 different locations. Jger wrote: "I can state today that the goal of

Einsatzkommando III alone in the

solving the Jewish problem in Lithuania has been reached by

five-month period covered by the

Einsatzkommando 3. There are no more Jews in Lithuania, apart from

report as 137,346.

working Jews and their families."[126] In a February 1942 addendum to

the report, Jger increased the total number of victims to 138,272, giving

a breakdown of 48,252 men, 55,556 women, and 34,464 children. Only 1,851 of the victims were

non-Jewish.[129]

Jger escaped capture by the Allies when the war ended. He lived in Heidelberg under his own name until his

report was discovered in March 1959.[130] Arrested and charged, Jger committed suicide on 22 June 1959 in a

Hohenasperg prison while awaiting trial for his crimes.[131]

The killings took place with the knowledge and support of the German Army in the east.[132] On 10 October

1941 Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau drafted an order to be read to the German Sixth Army on the

Eastern Front. Now known as the Severity Order, it read in part:

The most important objective of this campaign against the Jewish-Bolshevik system is the complete

destruction of its sources of power and the extermination of the Asiatic influence in European

civilization ... In this eastern theatre, the soldier is not only a man fighting in accordance with the

rules of the art of war, but also the ruthless standard bearer of a national conception ... For this

reason the soldier must learn fully to appreciate the necessity for the severe but just retribution that

must be meted out to the subhuman species of Jewry.[133]

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt of Army Group South expressed his "complete agreement" with the order.

He sent out a circular to the generals under his command urging them to release their own versions and to

impress upon their troops the need to exterminate the Jews.[134] General Erich von Manstein, in an order to his

troops on 20 November, stated that "the Jewish-Bolshevist system must be exterminated once and for all."[132]

Manstein sent a letter to Einsatzgruppe D commanding officer Ohlendorf complaining that it was unfair that the

SS was keeping all of the murdered Jews' wristwatches for themselves instead of sharing with the army.[135]

Beyond this trivial complaint, the Army and the Einsatzgruppen worked closely and effectively. On 6 July 1941

Einsatzkommando 4b of Einsatzgruppe C reported that "Armed forces surprisingly welcome hostility against

the Jews".[136] On 8 September, Einsatzgruppe D reported that relations with the German Army were

"excellent".[136] In the same month, Stahlecker of Einsatzgruppe A wrote that Army Group North had been

exemplary in co-operating with the exterminations and that relations with the 4th Panzer Army, commanded by

General Erich Hoepner, were "very close, almost cordial".[137] In the south, the Romanian Army worked closely

with Einsatzgruppe D to massacre Ukrainian Jews,[98] killing around 26,000 Jews in the Odessa massacre.[138]

The German historian Peter Longerich thinks it probable that the Wehrmacht, along with the Organization of

Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), incited the Lviv pogroms, during which 8,500 to 9,000 Jews were killed by the

native population and Einsatzgruppe C in July 1941.[139] Moreover, most people on the home front in Germany

had some idea of the massacres being committed by the Einsatzgruppen.[140] British historian Hugh

Trevor-Roper noted that although Himmler had forbidden photographs of the killings, it was common for both

the men of the Einsatzgruppen and for bystanders to take pictures to send to their loved ones, which he felt

suggested widespread approval of the massacres.[141]

The Wehrmacht tried to justify their considerable involvement in the Einsatzgruppen massacres as being

anti-partisan operations rather than racist attacks, but Hillgruber wrote that this was just an excuse. He states

that those German generals who claimed that the Einsatzgruppen were a necessary anti-partisan response were

lying, and maintained that the slaughter of about 2.2 million defenceless civilians for reasons of racist ideology

cannot be justified.[142]

After the close of the World War II, 24 senior leaders of the Einsatzgruppen were prosecuted in the

Einsatzgruppen Trial in 194748, part of the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials held under United States military

authority. The men were charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in the SS (which

had been declared a criminal organization). Fourteen death sentences and two life sentences were among the

judgments; only four executions were carried out, on 7 June 1951; the rest were reduced to lesser sentences.

Four additional Einsatzgruppe leaders were later tried and executed by other nations.[143]

Several Einsatzgruppen leaders, including Ohlendorf, claimed at the trial to have received an order before

Operation Barbarossa requiring them to murder all Soviet Jews.[144] To date no evidence has been found that

such an order was ever issued.[145] German prosecutor Alfred Streim noted that if such an order had been given,

post-war courts would only have been able to convict the Einsatzgruppen leaders as accomplices to mass

murder. However, if it could be established that the Einsatzgruppen had committed mass murder without orders,

then they could have been convicted as perpetrators of mass murder, and hence could have received stiffer

sentences, including capital punishment.[146]

Streim postulated that the existence of an early comprehensive order was a fabrication created for use in

Ohlendorf's defence. This theory is now widely accepted by historians.[147] Longerich notes that most orders

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

14 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

received by the Einsatzgruppen leadersespecially when they were being

ordered to carry out criminal activitieswere vague, and couched in

terminology that had a specific meaning for members of the regime. Leaders

were given briefings about the need to be "severe" and "firm"; all Jews were to

be viewed as potential enemies that had to be dealt with ruthlessly.[148] British

historian Sir Ian Kershaw argues that Hitler's apocalyptic remarks before

Barbarossa about the necessity for a war without mercy to "annihilate" the

forces of "Judeo-Bolshevism" were interpreted by Einsatzgruppen commanders

as permission and encouragement to engage in extreme antisemitic violence,

with each Einsatzgruppen commander to use his own discretion about how far

he was prepared to go.[149]

Most of the perpetrators of Nazi war crimes were never charged, and returned

unremarked to civilian life. The West German Central Prosecution Office of

Otto Ohlendorf, 1943

Nazi War Criminals only charged about a hundred former Einsatzgruppe

members with war crimes.[150] And as time went on, it became more difficult to

obtain prosecutions; witnesses grew older and were less likely to be able to offer valuable testimony. Funding

for trials was inadequate, and the governments of Austria and Germany became less interested in obtaining

convictions for wartime events, preferring to forget the Nazi past.[151]

Functionalism versus intentionalism

Glossary of Nazi Germany

List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

Porajmos

Citations

1. LEO Dictionary.

2. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

3. Edeiken 2000.

4. Streim 1989, p. 436.

5. Longerich 2012, pp. 405, 412.

6. Nuremberg Trial, Vol. 20, Day 194.

7. Longerich 2010, pp. 138141.

8. Longerich 2012, p. 425.

9. Longerich 2010, p. 144.

10. Evans 2008, p. 17.

11. Browning & Matthus 2004, pp. 1618.

12. Longerich 2010, p. 143.

13. Longerich 2010, pp. 144145.

14. Longerich 2012, p. 429.

15. Evans 2008, p. 15.

16. Longerich 2012, pp. 430432.

17. Weale 2012, p. 225.

18. Evans 2008, p. 18.

19. Gerwarth 2011, p. 147.

20. Longerich 2010, p. 146.

21. Evans 2008, pp. 2526.

22. Weale 2012, pp. 227228.

23. Weale 2012, pp. 242245.

24. Hillgruber 1989, p. 95.

25. Longerich 2012, pp. 521522.

26. Hillgruber 1989, pp. 9596.

27. Rhodes 2002, pp. 14, 48.

28. Hillgruber 1989, pp. 9495.

29. Hillgruber 1989, pp. 9496.

30. Hillgruber 1989, p. 96.

31. Longerich 2010, p. 181.

32. Longerich 2010, p. 185.

33. Rees 1997, p. 177.

34. Rhodes 2002, p. 15.

35. Browning 1998, pp. 1012.

36. Einsatzgruppen judgment, pp. 414416.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

15 of 18

37. Browning 1998, pp. 135136, 141142.

38. Robertson.

39. Browning 1998, p. 10.

40. Longerich 2010, p. 186.

41. Browning & Matthus 2004, pp. 225226.

42. MacLean 1999, p. 23.

43. Museum of Tolerance.

44. Longerich 2010, p. 419.

45. Dams & Stolle 2012, p. 168.

46. Conze, Frei et al. 2010.

47. Crowe 2007, p. 267.

48. Mallmann & Cppers 2006, p. 97.

49. Larsen 2008, p. xi.

50. Shelach 1989, p. 1169.

51. Longerich 2010, p. 197.

52. Mallmann, Cppers & Smith 2010, p. 130.

53. Longerich 2012, p. 523.

54. Longerich 2010, p. 198.

55. Hillgruber 1989, p. 97.

56. Hilberg 1985, p. 368.

57. Headland 1992, pp. 6270.

58. Urban 2001.

59. Longerich 2012, p. 526.

60. Haberer 2001, p. 68.

61. Longerich 2010, pp. 193195.

62. Longerich 2010, p. 208.

63. Longerich 2010, pp. 196202.

64. Longerich 2010, p. 207.

65. Longerich 2010, p. 208, 211.

66. Longerich 2010, p. 211.

67. Longerich 2010, pp. 211212.

68. Longerich 2010, pp. 212213.

69. Headland 1992, pp. 5758.

70. Rhodes 2002, p. 179.

71. Evans 2008, p. 227.

72. Weale 2012, p. 315.

73. Rhodes 2002, pp. 172173.

74. Rhodes 2002, pp. 173176.

75. Rhodes 2002, p. 178.

76. Weale 2012, p. 317.

77. Hillgruber 1989, p. 98.

78. Rhodes 2002, p. 41.

79. Haberer 2001, pp. 6768.

80. Rees 1997, p. 179.

81. Haberer 2001, pp. 6869.

82. Haberer 2001, p. 69.

83. Haberer 2001, p. 71.

84. Haberer 2001, pp. 6970.

85. Haberer 2001, p. 70.

86. Rees 1997, p. 182.

87. Haberer 2001, p. 66.

88. Haberer 2001, p. 73.

89. Haberer 2001, pp. 7475.

90. Haberer 2001, p. 76.

91. Haberer 2001, p. 77.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

92. Rhodes 2002, pp. 206209.

93. Rhodes 2002, pp. 208210.

94. Rhodes 2002, pp. 210214.

95. Hilberg 1985, p. 342.

96. Longerich 2012, p. 549.

97. Hilberg 1985, pp. 342343.

98. Marrus 2000, p. 64.

99. Hilberg 1985, p. 372.

100. Haberer 2001, p. 78.

101. Longerich 2010, p. 353354.

102. Rees 1997, p. 197.

103. Rhodes 2002, pp. 52, 124, 168.

104. Ingrao 2013, pp. 199200.

105. Rhodes 2002, p. 163.

106. Rhodes 2002, pp. 165166.

107. Longerich 2012, pp. 547548.

108. Rhodes 2002, p. 167.

109. Longerich 2012, p. 551.

110. Longerich 2012, p. 548.

111. Rhodes 2002, p. 243.

112. Longerich 2010, pp. 280281.

113. Longerich 2012, pp. 555556.

114. Longerich 2010, pp. 279280.

115. Rhodes 2002, p. 248.

116. Rhodes 2002, pp. 258260, 262.

117. Rhodes 2002, p. 257.

118. Evans 2008, p. 318.

119. Mallmann, Cppers & Smith 2010, p. 118.

120. Mallmann, Cppers & Smith 2010, pp. 124125.

121. Mallmann, Cppers & Smith 2010, pp. 127130.

122. Weinberg 2011.

123. Mallmann, Cppers & Smith 2010, p. 117.

124. Krumenacker 2006.

125. Shirer 1960, pp. 783784.

126. Rhodes 2002, p. 215.

127. Rhodes 2002, p. 126.

128. Longerich 2010, p. 230.

129. Rhodes 2002, p. 216.

130. Rabitz 2011.

131. Rhodes 2002, p. 276.

132. Hillgruber 1989, p. 102.

133. Craig 1973, p. 10.

134. Mayer 1988, p. 250.

135. Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 43.

136. Hilberg 1985, p. 301.

137. Hilberg 1985, p. 30.

138. Marrus 2000, p. 79.

139. Longerich 2010, p. 194.

140. Marrus 2000, p. 88.

141. Klee, Dressen & Riess 1991, p. xi.

142. Hillgruber 1989, pp. 102103.

143. Rhodes 2002, pp. 274275.

144. Longerich 2010, p. 187.

145. Longerich 2010, pp. 187189.

146. Streim 1989, p. 439.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

16 of 18

147. Longerich 2010, p. 188.

148. Longerich 2010, p. 189190.

149. Kershaw 2008, pp. 258259.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

150. Rhodes 2002, pp. 275276.

151. Segev 2010, pp. 226, 250, 376.

Books and journal articles

Browning, Christopher; Matthus, Jrgen (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish

Policy, September 1939 March 1942. Comprehensive History of the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska

Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1327-2.

Conze, Eckart; Frei, Norbert; Hayes, Peter; Zimmermann, Moshe (2010). Das Amt und die Vergangenheit : deutsche

Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik (in German). Munich: Karl Blessing.

ISBN 978-3-89667-430-2.

Craig, William (1973). Enemy at the Gates: The Battle for Stalingrad. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky.

ISBN 1-56852-368-8.

Crowe, David (2007) [2004]. Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of his Life, Wartime Activities and the True Story

Behind the List. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00253-5.

Dams, Carsten; Stolle, Michael (2012) [2008]. Die Gestapo: Herrschaft und Terror im Dritten Reich. Becksche Reihe

(in German). Munich: Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-62898-6.

Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

Haberer, Erich (2001). "Intention and Feasibility: Reflections on Collaboration and the Final Solution". East

European Jewish Affairs 31 (2): 6481. doi:10.1080/13501670108577951. OCLC 210897979.

Headland, Ronald (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Security Police and the Security

Service. London: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.

Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 978-0-8419-0832-1.

Hillgruber, Andreas (1989). "War in the East and the Extermination of the Jews". In Marrus, Michael. Part 3, The

"Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder, Volume 1. The Nazi Holocaust. Westpoint, CT: Meckler.

pp. 85114. ISBN 0-88736-266-4.

Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, MA: Polity.

ISBN 978-0-7456-6026-4.

Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

ISBN 978-0-300-12427-9.

Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker (1991). "The Good Old Days" The Holocaust as Seen by its Perpetrators

and Bystanders. Trans. Burnstone, Deborah. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-917425-2. (originally published as

Klee, Ernst; Dreen, Willi; Rie, Volker (Hrsg.) (1988). Schne Zeiten. Judenmord aus der Sicht der Tter und

Gaffer. (in German). Frankfurt / Main: S. Fischer. ISBN 978-3-10-039304-3.

Larsen, Stein Ugelvik (2008). Meldungen aus Norwegen 19401945: Die geheimen Lagesberichte des Befehlshabers

der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in Norwegen, 1 (in German). Munich: Oldenburg. ISBN 978-3-486-55891-3.

Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford

University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

MacLean, French L. (1999). The Field Men: The SS Officers Who Led the EinsatzkommandosThe Nazi Mobile

Killing Units. Schiffer Military History. Madison, WI: Schiffer. ISBN 978-0-7643-0754-6.

Mallmann, Klaus-Michael; Cppers, Martin (2006). Crescent and Swastika: The Third Reich, the Arabs and

Palestine. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-3-534-19729-3.

Mallmann, Klaus-Michael; Cppers, Martin; Smith, Krista (2010). Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of

the Jews in Palestine. New York: Enigma. ISBN 1-929631-93-6.

Marrus, Michael (2000). The Holocaust in History. Toronto: Key Porter. ISBN 978-1-55263-120-1.

Mayer, Arno J (1988). Why Did The Heavens Not Darken?. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-57154-1.

Rees, Laurence (1997). The Nazis: A Warning From History. Foreword by Sir Ian Kershaw. New York: New Press.

ISBN 1-56584-551-X.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

17 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

Rhodes, Richard (2002). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York:

Vintage Books. ISBN 0-375-70822-7.

Segev, Tom (2010). Simon Wiesenthal: The Life and Legends. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51946-5.

Shelach, Menachem (1989). "Sajmite: An Extermination Camp in Serbia". In Marrus, Michael Robert. The Victims

of the Holocaust: Historical Articles on the Destruction of European Jews 2. Westport, CT: Meckler.

Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster.

ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular

Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83365-3.

Streim, Alfred (1989). "The Tasks of the SS Einsatzgruppen, pages 436454". In Marrus, Michael. The Nazi

Holocaust, Part 3, The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder, Volume 2. Westpoint, CT: Meckler.

ISBN 0-88736-266-4.

Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York; Toronto: Penguin Group.

ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

Weinberg, Gerhard (July 2011). "Some Myths of World War II" (PDF). Journal of Military History (75): 701718.

Retrieved 2 April 2013.

Online sources

Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. "Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in

Poland" (PDF). London; New York: Penguin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved

2 January 2015.

Edeiken, Yale F. (22 August 2000). "Introduction to the Einsatzgruppen". Holocaust History Project. Retrieved

10 January 2013.

"Einsatzgruppen case" (PDF). Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council

Law No. 10 (PDF). Green Series. Volume 4. Nrnberg. October 1946 April 1949. Retrieved 2 April 2013. (also

available in a well indexed HTML version at Mazel library (http://www.mazal.org/NMT-HOME.htm))

Krumenacker, Thomas (7 April 2006). "Nazis Planned Holocaust for Palestine: historians". Red Orbit. Retrieved

3 April 2013.

LEO Dictionary Team. "LEO Deutsch-Englisches Wrterbuch "einsatzgruppe" " (in German). Dict.leo.org. Retrieved

10 January 2013.

"Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, Volume 20, Day 194". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law

Library. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

Rabitz, Cornelia (21 June 2011). "Biography of Nazi criminal meets resistance from small German town". dw.de.

Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

"Reflections on the Holocaust: "The Einsatzgruppen" ". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

Robertson, Struan. "The genocidal missions of Reserve Police Battalion 101 in the General Government (Poland)

19421943". Hamburg Police Battalions during the Second World War. Regionalen Rechenzentrum der Universitt

Hamburg. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

"Book review: Tasks of the Einsatsgruppen by Alfred Streim". Museum of Tolerance Online Multimedia Learning

Center, Annual 4, Chapter 9. Los Angeles: Simon Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

Urban, Thomas (1 September 2001). "Poszukiwany Hermann Schaper". Rzeczpospolita (newspaper) (in Polish)

(204). Archived from the original on 24 November 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

Earl, Hilary (2009). The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial, 19451958: Atrocity, Law, and History.

Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45608-1.

Frster, Jrgen (1998). "Complicity or Entanglement? The Wehrmacht, the War and the Holocaust". In

Berenbaum, Michael; Peck, Abraham. The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the

Disputed and the Reexamined. Bloomington: Indian University Press. pp. 266283.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

Einsatzgruppen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

18 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einsatzgruppen

ISBN 978-0-253-33374-2.

Krausnick, Helmut; Wilhelm, Hans-Heinrich (1981). Die Truppe des Weltanschauungskrieges. Die

Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD 19381942 (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche VerlagsAnstalt. ISBN 3-421-01987-8.

Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books.

ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

Stang, Knut (1996). Kollaboration und Massenmord. Die litauische Hilfspolizei, das Rollkommando

Hamann und die Ermordung der litauischen Juden (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

ISBN 3-631-30895-7.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum article on

Einsatzgruppen (http://www.ushmm.org

/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005130)

"Einsatzgruppen" (http://www.holocaustresearchproject.net

/einsatz/index.html) The Holocaust Education & Archive

Research Team

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org

/w/index.php?title=Einsatzgruppen&oldid=702032295"

Wikimedia Commons has

media related to

Einsatzgruppen.

Wikisource has original

text related to this article:

Comprehensive report

of Einsatzgruppe A up

to 15 October 1941

Categories: Nazi SS Einsatzgruppen Holocaust antisemitic attacks and incidents

Military units and formations of Germany in World War II The Holocaust in Ukraine

The Holocaust in Latvia The Holocaust in Lithuania The Holocaust in Estonia The Holocaust in Russia

The Holocaust in Belarus The Holocaust in Poland Holocaust terminology Gestapo Reinhard Heydrich

Reich Main Security Office Police of Nazi Germany

This page was last modified on 28 January 2016, at 00:53.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may

apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered

trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

1/31/2016 8:42 PM

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- German Railroads, Jewish Souls: The Reichsbahn, Bureaucracy, and the Final SolutionDe la EverandGerman Railroads, Jewish Souls: The Reichsbahn, Bureaucracy, and the Final SolutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nazi Concentration CampsDocument20 paginiNazi Concentration Campsivandamljanovic007Încă nu există evaluări

- Reluctant Accomplice: A Wehrmacht Soldier's Letters from the Eastern FrontDe la EverandReluctant Accomplice: A Wehrmacht Soldier's Letters from the Eastern FrontÎncă nu există evaluări

- Facing a Holocaust: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1943-1945De la EverandFacing a Holocaust: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1943-1945Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Death In The Forest; The Story Of The Katyn Forest MassacreDe la EverandDeath In The Forest; The Story Of The Katyn Forest MassacreEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- The War The Infantry Knew, 1914-1919: A Chronicle Of Service In France And BelgiumDe la EverandThe War The Infantry Knew, 1914-1919: A Chronicle Of Service In France And BelgiumEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (14)

- Rethinking Holocaust Justice: Essays across DisciplinesDe la EverandRethinking Holocaust Justice: Essays across DisciplinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unsettled Heritage: Living next to Poland's Material Jewish Traces after the HolocaustDe la EverandUnsettled Heritage: Living next to Poland's Material Jewish Traces after the HolocaustÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitler's War and the Horrific Account of the HolocaustDe la EverandHitler's War and the Horrific Account of the HolocaustÎncă nu există evaluări

- From "Euthanasia" to Sobibor: An SS Officer's Photo CollectionDe la EverandFrom "Euthanasia" to Sobibor: An SS Officer's Photo CollectionMartin CüppersÎncă nu există evaluări

- German Colonialism: Race, the Holocaust, and Postwar GermanyDe la EverandGerman Colonialism: Race, the Holocaust, and Postwar GermanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilhelm Höttl and The Elusive 6 MillionDocument12 paginiWilhelm Höttl and The Elusive 6 MillionGuy Razer100% (1)

- Nitzotz: The Spark of Resistance in Kovno Ghetto and Dachau-Kaufering Concentration CampDe la EverandNitzotz: The Spark of Resistance in Kovno Ghetto and Dachau-Kaufering Concentration CampÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gulag Literature and the Literature of Nazi Camps: An Intercontexual ReadingDe la EverandGulag Literature and the Literature of Nazi Camps: An Intercontexual ReadingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence For The Implementation of The Final Solution: Electronic Edition, by Browning, Christopher RDocument42 paginiEvidence For The Implementation of The Final Solution: Electronic Edition, by Browning, Christopher RBleedingSnowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genocide in A Small Place Wehrmacht Complicit in Killing The Jews of Krupki, 1941Document33 paginiGenocide in A Small Place Wehrmacht Complicit in Killing The Jews of Krupki, 1941Lily MazlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Out of Passau: Leaving a City Hitler Called HomeDe la EverandOut of Passau: Leaving a City Hitler Called HomeEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1)

- The Tragic Conservatism of Ernest Hemingway: And Other Essays Including the Neocon CabalDe la EverandThe Tragic Conservatism of Ernest Hemingway: And Other Essays Including the Neocon CabalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Terror Flyers: The Lynching of American Airmen in Nazi GermanyDe la EverandTerror Flyers: The Lynching of American Airmen in Nazi GermanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Between Mass Death and Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century GermanyDe la EverandBetween Mass Death and Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century GermanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- War, Genocide and Cultural Memory: The Waffen-SS, 1933 to TodayDe la EverandWar, Genocide and Cultural Memory: The Waffen-SS, 1933 to TodayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jews in Nazi Berlin: From Kristallnacht to LiberationDe la EverandJews in Nazi Berlin: From Kristallnacht to LiberationEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- Terror Alert: 1970--The Strange Summer of Bomb Threats in MinnesotaDe la EverandTerror Alert: 1970--The Strange Summer of Bomb Threats in MinnesotaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945De la EverandHitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- Witnessing Unbound: Holocaust Representation and the Origins of MemoryDe la EverandWitnessing Unbound: Holocaust Representation and the Origins of MemoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weimar Radicals: Nazis and Communists between Authenticity and PerformanceDe la EverandWeimar Radicals: Nazis and Communists between Authenticity and PerformanceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intimate Violence: Anti-Jewish Pogroms on the Eve of the HolocaustDe la EverandIntimate Violence: Anti-Jewish Pogroms on the Eve of the HolocaustÎncă nu există evaluări

- GIs and Fräuleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West GermanyDe la EverandGIs and Fräuleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West GermanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comrades Betrayed: Jewish World War I Veterans under HitlerDe la EverandComrades Betrayed: Jewish World War I Veterans under HitlerÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Virtuous Wehrmacht: Crafting the Myth of the German Soldier on the Eastern Front, 1941-1944De la EverandThe Virtuous Wehrmacht: Crafting the Myth of the German Soldier on the Eastern Front, 1941-1944Încă nu există evaluări

- A Jewish Kapo in Auschwitz: History, Memory, and the Politics of SurvivalDe la EverandA Jewish Kapo in Auschwitz: History, Memory, and the Politics of SurvivalÎncă nu există evaluări

- SS Hunter Battalions: The Hidden History of the Nazi Resistance Movement 1944-5De la EverandSS Hunter Battalions: The Hidden History of the Nazi Resistance Movement 1944-5Încă nu există evaluări

- Hitler's Stormtroopers: The SA, The Nazis' Brownshirts, 1922–1945De la EverandHitler's Stormtroopers: The SA, The Nazis' Brownshirts, 1922–1945Încă nu există evaluări

- The Nazi Hunters. How A Team of Spies and Survivors Captured The World's Most Notorious Naz (PDFDrive)Document232 paginiThe Nazi Hunters. How A Team of Spies and Survivors Captured The World's Most Notorious Naz (PDFDrive)karthikavinodcanadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Annihilation of Superfluous EatersDocument10 paginiThe Annihilation of Superfluous EatersPatrickRosenbergÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warsaw Ghetto Police: The Jewish Order Service during the Nazi OccupationDe la EverandWarsaw Ghetto Police: The Jewish Order Service during the Nazi OccupationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Germany's War and the Holocaust: Disputed HistoriesDe la EverandGermany's War and the Holocaust: Disputed HistoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (4)

- Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich (: Reichsprotektor (Deputy/Acting Reich-Protector) of BohemiaDocument20 paginiReinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich (: Reichsprotektor (Deputy/Acting Reich-Protector) of BohemiaZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nazi GermanyDocument40 paginiNazi GermanyZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), Rendered in English As: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument9 paginiSS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), Rendered in English As: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaZoth Bernstein100% (1)

- UnitasDocument2 paginiUnitasZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brahma Temple, PushkarDocument5 paginiBrahma Temple, PushkarZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- DurgaDocument8 paginiDurgaZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- KamaDocument7 paginiKamaZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mutant ChroniclesDocument3 paginiMutant ChroniclesZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- SanskritDocument15 paginiSanskritZoth Bernstein0% (1)

- Hindu TextsDocument9 paginiHindu TextsZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- BhramariDocument2 paginiBhramariZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- ArunasuraDocument2 paginiArunasuraZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devi MahatmyaDocument10 paginiDevi MahatmyaZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Enochian AngelsDocument23 paginiList of Enochian AngelsZoth Bernstein100% (1)

- PurgatoryDocument22 paginiPurgatoryZoth Bernstein100% (1)

- QliphothDocument6 paginiQliphothZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- AstarothDocument2 paginiAstarothZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- KultDocument5 paginiKultZoth Bernstein0% (1)

- TutuDocument2 paginiTutuZoth Bernstein0% (1)

- Isaac LuriaDocument5 paginiIsaac LuriaZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- UgaritDocument8 paginiUgaritZoth BernsteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarterly Progress Report FormatDocument7 paginiQuarterly Progress Report FormatDegnesh AssefaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 9 Organic Law On Provincial and Local-Level Government (OLPLLG) - SlidesDocument29 paginiUnit 9 Organic Law On Provincial and Local-Level Government (OLPLLG) - SlidesMark DemÎncă nu există evaluări

- MSU-Iligan Institute of TechnologyDocument5 paginiMSU-Iligan Institute of TechnologyYuvi Rociandel LUARDOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quinta RuedaDocument20 paginiQuinta RuedaArturo RengifoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 7 Worksheet No. 1 2Document24 paginiGroup 7 Worksheet No. 1 2calliemozartÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coalition TacticsDocument2 paginiCoalition Tacticsakumar4u100% (1)

- B65a RRH2x40-4R UHGC SPDocument71 paginiB65a RRH2x40-4R UHGC SPNicolás RuedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ego and Analysis of Defense-Jason Aronson, Inc. (2005) Paul GrayDocument356 paginiThe Ego and Analysis of Defense-Jason Aronson, Inc. (2005) Paul GrayClinica MonserratÎncă nu există evaluări