Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Acne Vulgaris: Prevalence and Clinical Forms in Adolescents From São Paulo, Brazil

Încărcat de

Alyani Akramah BasarTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Acne Vulgaris: Prevalence and Clinical Forms in Adolescents From São Paulo, Brazil

Încărcat de

Alyani Akramah BasarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

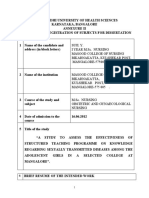

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 428

428

INVESTIGATION

Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents

from So Paulo, Brazil*

Edilia Bagatin1

Lilia Ramos dos Santos Guadanhim1

Luiz Roberto Terzian3

Mercedes Florez4

Denise Loureno Timpano1

Vanessa Mussupapo Andraus Nogueira2

Denise Steiner2

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142100

Abstract: BACKGROUND: Acne is a common disease in adolescents, but there are no epidemiological data for acne

in Brazil.

OBJECTIVES: To estimate the prevalence and degree of acne in adolescents from Sao Paulo and study socio-demographic factors, family history and lifestyle, associated with the disease.

METHODS: Cross-sectional study with 452 adolescents aged between 10 and 17 (mean=13.3 years), students from

elementary and high school, examined by 3 independent evaluators.

RESULTS: 62.4% were female, 85.8% white and 6.4% were aged 14. The prevalence was 96.0% and increased with

age - all students over 14 had acne. The most prevalent form of acne was comedonal (61.1%), followed by mild

(30.6%) and moderate (7.6%) papular-pustular, which affected mostly the face (97.5%). About half of the adolescents reported family history for acne in mother or father, and 20.6% reported previous treatment for acne. There

was a higher chance of presenting non-comedonal acne with increased age (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION: The prevalence of acne in adolescents varies widely due to the clinical features and diagnostic methods used. Adolescents whose brothers/sisters had acne (OR=1.7-p=0.027) and those over 13 (OR=8.3p<0.001), were more likely to have non-comedonal acne.

CONCLUSION: This study showed high prevalence of acne in adolescents from Sao Paulo, predominantly the comedonal form on the face, with a higher chance of presenting non-comedonal acne with increased age.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris; Demographic data; Family characteristics; Prevalence; Socioeconomic factors

INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease

of the pilosebaceous follicles, common in adolescents,

characterized by comedones, papules, pustules, cysts,

nodules, and occasionally scars. Its pathogenesis

includes follicular hyperkeratinization, sebaceous

hypersecretion due to androgen stimulation, follicular

colonization by Propionibacterium acnes, immune and

inflammatory responses. It affects the face, anterior

chest and upper back.1

The prevalence of acne in adolescents and

2-11

adultsvaries among countries and ethnic groups. In

Australia, acne was observed in 27.7% of students

aged 10-12 and in 93.3% of adolescents aged 16-18. A

study in Peru reported a prevalence of 16.33% and

71.23%, in students aged 12 and 17, respectively.2 In

Received on 31.08.2012.

Approved by the Advisory Board and accepted for publication on 02.03.2013.

* Work performed at the Department of Dermatology - Federal University of Sao Paulo (UNIFESP) - Sao Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Financial Support: Laboratrio Stiefel.

Conflict of Interest: Estudo apoiado pelo Laboratrio Stiefel.

1

2

3

4

Universidade Federal de So Paulo (UNIFESP) So Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Universidade de Mogi das Cruzes (UMC) Mogi das Cruzes (SP), Brazil.

Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (FMABC) Santo Andr (SP), Brazil.

Private clinic - Miami, FL, Estados Unidos.

2014 by Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 429

Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents from So Paulo, Brazil

countries including Belgium and China, prevalence in

adolescents is high, about 90%, while in England it is

estimated at 50%. It is generally assumed that acne

occurs in 70-80% of adolescentes.12,13

A Chinese study observed no disease in children under 10 and a prevalence of 1.6% at the age of

10, which increased with age, reaching 46.8% by the

age of 19, then decreased progressively, and was rare

in individuals aged over 50. In this study, 68.4% of

subjects had mild acne, 26.0% moderate and 5.6%

severe. Only a third of them had been treated before

(39.0% female and 29.6% males). Acne was more

prevalent in adolescent men and adult women.1 Two

studies in the UK reported similar results.4,8

In the US, acne is the fourth most common reason for seeking medical consultation among patients

aged 11- 21, and it accounts for 4% of all visits from

patients aged 15-19.14-16 Different studies have shown

prevalence rates ranging from 28.9-91.3% in adolescents.2,6,14,17,18

In Brazil, acne accounts for approximately 14%

of dermatological consultations and affects both genders, different ethnicities and all age groups, predominantly in the first three decades of life.19

As there are no epidemiological data on the

prevalence of acne in Brazil, the objective of this study

was: to estimate the prevalence and degree of acne in

adolescents from So Paulo (by gender and age

group); analyze the diagnostic convergence regarding

acne among three dermatologists; and study sociodemographic factors, family history and lifestyle associated with the occurrence and severity of the disease.

METHODS

Cross-sectional study including 452 adolescents

aged 10-17, elementary and high school students from

two public and two private institutions in So Paulo,

examined by three evaluators (A, B, C).

The study population lives in So Paulo city,

which has 11,253,503 inhabitants, 867,351 aged 10-14,

and 841,081 aged 15-19 (Source: IBGE, Brazilian

Demographic Census, 2010). In addition to those born

in the city, there are citizens from all regions of Brazil,

as it is the greatest economic and industrial center in

the country, with numerous employment opportunities, as well as a large number of academic and cultural options. However, because of its size and heterogeneous living conditions, many social problems exist. It

is estimated that there are 2,895 public schools and

2,748 private schools. Regarding elementary education, 644,804 students are registered at public schools

and 137,024 at private schools; while the numbers for

high school are 380,035 students at public schools and

78,274 at private schools (Source: School Census MEC

/ Inep and Educational Information Center of State

429

Department of Education 2008).

The sample size was based on Rademakers

study (1989),20 in which the prevalence of acne in girls

ranged from 61% at the age of 12, to 83% at the age of

16 and, for boys, the equivalent rates were 40% and

95%, respectively. Assuming an average prevalence of

acne of 50%, at a confidence interval of 95%, and a

maximum error of 7.5%, the estimated sample was

of 171 adolescents from each gender. Taking into

account a possible loss of 50%, 257 male and 257

female adolescents were necessary.

Three reviewers assessed the presence or

absence of acne and its characteristics: clinical form

(comedonal, papular-pustular - mild, moderate or

severe, nodular-cystic - moderate or severe), age of

onset, location (face, trunk or both) and treatment

(age, duration and medication used).21 The characteristics of parents (education, previous history and age

of onset), socio-demographic factors and lifestyle conditions of the adolescents (age, gender, race, current

school grade, smoking and age of onset of smoking),

were also analyzed. For girls, the age of menarche and

oral contraceptive use were considered.

Agreement between the three evaluators was

gauged using kappa statistics (for presence or absence

of acne) and weighted kappa statistics (for the degree

of acne). Agreement is considered moderate

when0.4<0.6, good when 0.6<0.8 and very good

(almost perfect) when0.8.

The prevalence of acne, according to sex and

age, was estimated at a confidence interval of 95% (CI

= 95%). Factors associated with the occurrence of acne

were analyzed via the association test, using the chisquare test.

Upon analysis of factors associated with severity of acne, the dependent variable was the disease

form (comedonal or non comedonal) and the independent variables were gender, age, skin color (white,

black/brown and yellow), education levels of father

and mother, occurrence of acneandacne scarsin parents, and smoking. This analysis was conducted by

the association chi-square test or chi-square test for

trendand multiple logistic regression model. The final

result was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

The variables, presence of acne and acne scars in

parents were selected to illustrate the possible role of

genetic factors in the development and severity of the

disease. We also planned to correlate parents educational levels with willingness to seek medical treatment.

The double entry software Epi-Info (version

6.04) was used to treat all data, while consistency was

assessed through the validate command. Afterwards,

the databases were exported to the extensions xls

(Excel) and sav (SPSS), using the StatTransfer software

(version 2001 for Windows).

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 430

430

Bagatin E, Timpano DL, Guadanhim LRS, Nogueira VMA, Terzian LR, Steiner D, Florez M

In all analyses, we used SPSS for Windows (version 12.0) and the significance level considered was 5%.

RESULTS

In order to analyze diagnostic convergence for

acne among the three evaluators, 52 students (27 male,

25 female) from two classrooms at one school, aged

12-15 years were randomly selected.

The comparison between examiners A and B

revealed only one disagreement regarding the presence or absence of acne, and it was not possible to calculate the kappa statistic, because examiner B considered that all students had acne. In assessing the degree

of acne, the weighted kappa was 0.6, showing strong

agreement between the examiners.

Comparing evaluators A and C, there were four

disagreements concerning the presence of acne ( =

0.31) and strong agreement over the degree of acne

(p = 0.6).

The data provided by examiners B and C

revealed five discrepancies in comparing the presence

of acne, and it was not possible to calculate the kappa

statistic because examiner B considered that all students had acne. There was strong agreement between

examiners B and C when comparing the degree of

acne (p = 0.6).

Among the 452 adolescents evaluated, 62.4%

were female, 85.8% white and 6.4% were aged 14. The

age ranged from 10-17, with a mean of 13.3 (SD = 2.02

years), and median of 13.0.

Acne was present in 434 adolescents examined,

i.e., the prevalence was 96.0% (CI 95% [94.2;

97.8]). There was no difference between sexes (p =

0.856): male, 95.9% (IC 95% [92.9; 98.9]) and female,

96.1%(IC 95% [93.8; 98.4]).The prevalence increased

with age, but there were no differences at ages 10, 11,

12 and 13 (90.9%, 93.3%, 91.6% and 95.5% respectively, p=0,726 chi-square test of trend). All students

over 14 had acne and therefore the confidence interval

of 95% was not calculated.

Graph 1 shows that the most prevalent form of

acne was comedonal (61.1% - CI 95% [56.5%;

65.7%]), followed by mild (30.6% - CI 95% [26.3%;

34.9%]) and moderate (7.6% - CI 95% [5.1%; 10.1%])

papular-pustular.

Table 1 presents a description of the location and

age of acne onset. The most commonly affected site

was the face (97.5%) or the face and trunk(2.3%). The

age at which students experienced their first episodes

ranged from 2 to 16; a mean of 11.5 (SD = 1.6 years) and

median of 11.0, and the most prevalent age groups

were 11 and 12 years (50.4% of patients with acne).

Use of oral contraceptives was reported by only

four adolescents (0.9%). The age of menarche ranged

from 8 to 15, with a mean of 11.8 (SD = 1.1 years) and

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

GRAPH 1: Distribution of adolescents according to presence

and degree of acne

median of 12. Previous treatment for acne, such as

topical products, with or without skin cleansing

and oral medications, skin cleansing associated or

not with pill intake, and the use of oral medications,

was reported by 93 (20.6%) of the 452 adolescents.

Only 18 adolescents were able to recall the duration of

the treatment, which ranged from 1 to 35 months

(mean 6.3 months, SD = 8.1 months and median = 3.5

months).

Most parents had a college degree and about

half of the adolescents reported a family history of

acne in mothers or fathers. Almost all reported that

acne in parents occurred during adolescence. The

presence of acne scars was reported in 15.3% of fathers

and 13.3% of mothers (Table 2).

Presence of acne in other relatives was mentioned by 61.1% of the students, 32.5% in siblings,

34.1% in cousins and 14.4% in uncles/aunts.

Given that all teenagers over the age of 14 had

acne, analysis of associated factors was restricted to

those aged 10-13. There was no difference in acne

prevalence regarding skin color (92.1%, 100.0% and

93.3% for white, black / brown and yellow, respectively, p = 0.371), parents educational level (94.0 % vs.

92.4%, = 0.664 for father and 92.4% vs. 93.0%, p = 0.874

for mother) and family history of acne (96.8% vs.

90.6%, p = 0.118 for father; 90.6% vs. 94.2%, p = 0.289,

for mother; 91.4% vs. 93.6%, p = 0.558, for other relatives). At this age, no adolescents smoked and, therefore, the association has not been tested. Thus, since

there was no significant association between the presence of acne and the variables studied, analysis with

logistic regression models was not continued.

As there were few cases of non-comedonal

acne, lesions were classified into comedonal or noncomedonal acne. Table 3 shows a significant association between the form of acne, age and previous treatment, with a higher prevalence of comedonal acne (p

<0.001 for both). In accordance with Table 3, the

chances of presenting non-comedonal acne are higher

with increased age (chi-square test of trend - p for

trend <0.001).

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 431

Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents from So Paulo, Brazil

431

TABLE 1: Number and percentage of teenagers with acne, regarding affected area and age of onset

No.

CI 95%

Face

Face and trunk

Trunk

Age of onset

9 years

10 years

11 years

12 years

13 years

14 17 years

Dont know

423

10

1

97.5

2.3

0.2

[95.5% ; 98.6%]

[1.3% , 4.2%]

[0.0% ; 1.3%]

27

70

116

103

72

36

10

6.2

16.2

26.7

23.7

16.6

8.3

2.2

[4.3% ; 8.9%]

[13.0% ; 19.9%]

[22.8% ; 31.1%]

[20.0% ; 28.0%]

[13.4% ; 20.4%]

[6.1% ; 11.3%]

[1.3% ; 4.2%]

Total

434

100

Affected area

TABLE 2: Number and percentage of adolescents, according to parental characteristics

No.

CI 95%

Incomplete Basic Education

Basic Education

Incomplete High School

High School

Incomplete College

College

Unkown father/ignored

Father with acne

No

Yes. in adolescence

Yes. in adulthood

Unkown father/ignored

Father with acne scars

No

Yes

Unkown father/ignored

Mothers Educational level

Incomplete Basic Education

Basic Education

Incomplete High School

High School

Incomplete College

College

Unkown mother/ignored

Mother with acne

No

Yes. in adolescence

Yes. in adulthood

Unkown mother/ignored

Mother with acne scars

No

Yes

Unkown mother/ignored

26

9

5

63

17

284

48

5.8

2.0

1.1

13.9

3.8

62.8

10.6

[4.0% ; 8.3%]

[1.1% ; 3.7%]

[0.5% ; 2.6%]

[11.0% ; 17.4%]

[2.4% ; 5.9%]

[58.3% ; 67.2%]

[8.1% ; 13.8%]

165

144

1

142

36.5

31.9

0.2

31.4

[32.2% ; 41.0%]

[27.7% ; 36.3%]

[0.0% ; 1.2%]

[27.3% ; 35.8%]

333

69

50

73.6

15.3

11.1

[69.4% ; 77.5%]

[12.2% ; 18.9%]

[8.5% ; 14.3%]

25

16

6

79

14

284

28

5.5

3.5

1.3

17.5

3.1

62.8

6.3

[3.8% ; 8.0%]

[2.2% ; 5.7%]

[0.6% ; 2.9%]

[14.3% ; 21.2%]

[1.9% ; 5.1%]

[58.3% ; 67.2%]

[4.3% ; 8.8%]

189

165

7

91

41.8

36.5

1.5

20.1

[37.4% ; 46.4%]

[32.2% ; 41.0%]

[0.8% ; 3.2%]

[16.7% ; 24.1%]

368

60

24

81.4

13.3

5.3

[77.6% ; 84.7%]

[10.5% ; 16.7%]

[3.6% ; 7.8%]

Total

452

100

Fathers Educational level

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 432

432

Bagatin E, Timpano DL, Guadanhim LRS, Nogueira VMA, Terzian LR, Steiner D, Florez M

TABLE 3: Number and percentage of adolescents according to acne severity and characteristics of the adolescent.

Acne

Inflammatory

Comedonal

OR

CI 95%

Gender

p-value

0.615

Male

Female

108 (39.9%)

61 (37.4%)

163 (60.1%)

102 (62.6%)

1.108

1.000

Age (Years)

10/11

12

13

14

15

16

17

11 (11.7%)

22 (22.4%)

20 (47.6%)

23 (47.9%)

45 (58.4%)

18 (56.2%)

30 (69.8%)

83 (88.3%)

76 (77.6%)

22 (52.4%)

25 (52.1%)

32 (41.6%)

14 (43.8%)

13 (30.2%)

1.000

2.184

6.860

6.942

10.611

9.701

17.413

Skin color

White

Black/Brown

Yellow

146 (39.4%)

15 (36.6%)

8 (36.4%)

225 (60.6%)

26 (63.4%)

14 (63.6%)

1.000

0.889

0.881

Smoking

No

Yes

163 (38.4%)

6 (60.0%)

261 (61.6%)

4 (40.0%)

1.000

2.402

Previous Treatment

No

Yes

118 (34.6%)

47 (55.3%)

223 (65.4%)

38 (44.7%)

1.000

2.337

<0.001

[0.993 ; 4.802]

[2.865 ; 16.423]

[2.978 ; 16.181]

[4.888 ; 23.036]

[3.790 ; 24.831]

[7.044 ; 43.043]

0.912

[0.456 ; 1.735]

[0.360 ; 2.151]

0.198

[0.668 ; 8.640]

<0.001

[1.443 ; 3.786]

p: test Chi-square test

Gender, ethnicity and smoking did not reveal a

significant association with acne type (p> 0.05 for all).

Table 4 demonstrates a significant association

between the severity of acne and parents educational

level (p = 0.008 for father and p = 0.001 for mother),

with a higher prevalence of non-comedonal acne

among those who had studied up to high school level.

There was also a significant association between noncomedonal acne and the presence of the disease in siblings (p = 0.002), and no significant association regarding family history in fathers (p = 0.052),mothers (p =

0.085), uncles (p = 0.942) andcousins (p=0.365).

Table 5 presents the results of multiple analyses.

Independent factors associated with the severity of

acne were age and the presence of brothers/sisters with

acne, adjusted according to mothers educational level.

Adolescents whose brothers/sisters had acne and those

over 13 were more likely to have non-comedonal acne.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of acne in adolescents varies

widely in different studies, especially due to the clinical features and methods used, namely interviews

and/or clinical examinations by a dermatologist.

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

Clearly, patients perception of acne does not always

correspond to the diagnosis made by the doctor,

which explains discordant results when such comparisons are made.22 Moreover, we share the opinion of

some authors that the presence of open or closed

comedones, in any location, is sufficient to consider

the diagnosis of acne.23 Others defend that the presence of more than 20 lesions, including inflammatory

ones, is required for the diagnosis.24 A study with

4,191 subjects revealed an acne prevalence rate of

68.5% in boys and 59.6% in girls, with the presence of

one comedone considered suffiecient for the diagnosis. Another study encompassing 914 patients,

described a prevalence rate of only 27.9% for boys and

20.8% for girls.23 The average prevalence rate in adolescents ranges from 70 to 87%, without significant

differences between countries.23

In this study, the three evaluators diasagreed on

the diagnosis of acne. One reported that all adolescents

had acne. The presence of acne ranged from 90 to 100%

among the three examiners, and the average prevalence was 96%, higher than previously reported in the

literature.23 The examiners agreed on the severity of

acne, with a predominance of the comedonal form.

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 433

Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents from So Paulo, Brazil

433

TABLE 4: Number and percentage of adolescents according to acne severity and characteristics of parents and

other relatives. p: test Chi-square test

Acne

Inflammatory

Comedonal

OR

CI 95%

Fathers

Educational level

p-value

0.008

High School

College

70 (47.6%)

99 (34.6%)

77 (52.4%)

188 (65.5%)

1.726

1.000

[1.151 ; 2.588]

Mothers

Educational level

High School

College

74 (49.7%)

95 (33.3%)

75 (50.3%)

190 (66.7%)

1.973

1.000

[1.317 ; 2.958]

Father with acne?

No

Yes

52 (32.5%)

89 (42.6%)

108 (67.5%)

120 (57.4%)

1.000

1.540

Mother with acne?

No

Yes

62 (34.1%)

93 (42.5%)

120 (65.9%)

126 (57.5%)

1.000

1.429

Sibling with

acne?

No

Yes

78 (33.5%)

70 (49.3%)

155 (66.5%)

72 (50.7%)

1.000

1.932

Cousin with acne?

No

Yes

85 (37.6%)

63 (42.3%)

141 (62.4%)

86 (57.7%)

1.000

1.215

188 (60.5%)

39 (60.9%)

1.000

0.980

0.001

0.052

[1.002 ; 2.367]

0.085

[0.951 ; 2.146]

0.002

[1.261 ; 2.961]

0.365

Uncle/Aunt with acne

No

123 (39.5%)

Yes

25 (39.1%)

[0.797 ; 1.853]

0.942

A study that analyzed gender and age demonstrated that, among girls, 61% had acne at the age of

12, and 83% at 16, with higher incidence between the

ages of 15 and 17. Among boys, the prevalence of acne

was 40% at the age of 12, but increased to 95% at 16,

with a peak between 17 and 19 years. 20,23 Our analysis

found that the prevalence of acne in male adolescents

was 95.9%, with no difference in female adolescents

(96.1%), which increased with age.

Ninety three (20.6%) of the 452 adolescents

evaluated, reported previous treatment for acne. A

study in New Zealand showed that 67.3% of the students surveyed reported having acne and significantly more difficulty in accessing medical treatment,

compared with those who did not mention acne

(46.0% vs. 13.3%, OR 5.29). These differences persisted

after controlling for socioeconomic factors.17

Acne in younger patients is predominantly

non-inflammatory and differs from that observed

when onset occurs later. With age, the increased pro-

[0.565 ; 1.700]

duction of sebum settles, favoring skin colonization

by Propioniumbacterium acnes and other bacteria,

which trigger immune response and the development

of inflammatory lesions, such as papules, pustules,

and nodules. In the young, there are follicular plugs

and comedones, but the production of sebum is insufficient for bacterial growth.25

In this study, we observed a predominance of

comedonal acne up to the age of 12 and a tendency for

non-comedonal acne in adolescents over 13.

Currently, it is considered that the onset of acne occurs

earlier in girls (11 years) than in boys (12 years).12 A

study in Brazil showed that the average age of onset

of acne symptoms in females was 14.3 4.1

years.19 Recently, studies have reported early onset of

acne, at the age of 8 or 9, in line with epidemiological

data, suggesting earlier start of puberty.25

Table 3 shows an increase in the prevalence of

inflammatory acne and a decreased prevalence of

comedonal acne with increased age. According to

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 434

434

Bagatin E, Timpano DL, Guadanhim LRS, Nogueira VMA, Terzian LR, Steiner D, Florez M

TABLE 5: Multiple logistic regression model for factors associated with the severity of acne.

p (Hosmer-Lemeshow) = 0.546

OR Adjusted

Age (years)

10/11

12

13

14

15

16

17

1.0

2.2

8.3

7.1

10.1

9.4

17.0

Mothers Educational level

High School

College

1.5

1.0

Siblings with acne?

No

Yes

1.0

1.7

p-value

<0.001

0.061

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

0.110

0.027

Table 5, adolescents over 13 were more likely to have

non-comedonal acne. This study, along with others,

therefore confirms a higher severity of acne with

increased age.25

There is a possible bias in this cross-sectional

study. From the age of 13, the chances of presenting

inflammatory acne increased and, after 14, 100% of

the adolescents were diagnosed as having acne. Acne

severity usually increases with age. As the severe

forms are more persistent, the incidence of acne may

be higher when older students are examined.

Regarding the affected area, a study conducted

in five US cities noted that approximately 50% of

patients with acne vulgaris experienced lesions on the

trunk and/or back, while over 3% had lesions only on

the trunk. Approximately 1 in 4 patients did not mention the presence of acne in the trunk that was detected by clinical examination. Most cases of acne vulgaris

on the trunk were mild to moderate in severity, and

over 75% were interested in treatment for trunk

lesions.26 In constrast, our study reported acne on the

trunk in2.5%of the adolescents, and the face was the

most frequently affected site (97.5%).

An epidemiological study conducted in French

schools, comprising 913 adolescents aged 11-18,

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

reported that 16% of those with acne had positive

family histories for acne in their fathers, versus 8% of

those without acne.23,24 The equivalent data with

respect to mothers was 25%, versus 14% of those without acne. Among adolescents with acne, 68% of brothers and sisters also had acne, versus 57% in those

without the disease. It is known that family history of

acne in parents is most often associated with severe

acne or weaker response to oral drugs such as

cyclins.23 About half of the patients reported a parent

with history of acne, almost all during adolescence,

but there was no significant correlation between the

presence of acne in adolescents and fathers (p = 0.052)

or mothers (p = 0.085). The risk of inflammatory acne,

although slight, was greater among adolescents

whose siblings had the disease, which is consistent

with the literature and probably related to genetic factors. The same pattern was observed in relation to

lower educational levels of parents, which may mean

less concern with the disease or greater difficulty in

accessing early treatment.

This study demonstrated the presence of moderate and severe inflammatory acne in 8.3% of adolescents, which is lower than that reported in the literature (around 20%).12 The occurrence of these forms

ranged from 14% in Iranand 48% in Singapore.12,13

A Brazilian study that evaluated the prevalence

of dermatosis in school children aged 7-14, found

prevalence rates of 9% and 11% for comedonal acne,

and 19% and 5% for papular-pustular acne, respectively, in public and private schools.27 In our study,

there was no difference in prevalence between public

and private schools.

Limitations of this study include the sample

size and characteristics of the selected population.

Multicenter studies should be conducted to estimate

the prevalence of acne vulgaris in Brazil.

CONCLUSION

This study revealed a high prevalence of acne in

adolescents from So Paulo, Brazil, with a higher

prevalence of the comedonal form.Up to the age of 12,

we observed a predominance of comedonal acne and

a tendency for non-comedonal acne in adolescents

over 13.The only factor that determined the presence

of the disease was age, since 100% of the adolescents

over 14 were diagnosed with acne vulgaris. q

Revista3Vol89ingles-Bruno_Layout 1 5/20/14 1:10 PM Pgina 435

Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents from So Paulo, Brazil

435

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Shen Y, Wang T, Zhou C, Wang X, Ding X, Tian S, et al. Prevalence of acne vulgaris in

chinese adolescents and adults: a community-based study of 17,345 subjects in six

cities. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:40-4.

Kilkenny M, Merlin K, Plunkett A, Marks R. The prevalence of common skin conditions

in Australian school students: 3. acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:840-5.

Freyre EA, Rebaza RM, Sami DA, Lozada CP. The prevalence of facial acne in

Peruvian adolescents and its relation to their ethnicity. J Adolesc Health.

1998;22:480-4.

Cunliffe WJ, Gould DJ. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in

adults. Br Med J. 1979;1:1109-10.

Yahya H. Acne vulgaris in Nigerian adolescents - prevalence, severity, beliefs, perceptions, and practices. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:498-505.

Smithard A, Glazebrook C, Williams HC. Acne prevalence, knowledge about acne and

psychological morbidity in mid-adolescence: a community-based study. Br J

Dermatol. 2001;145:274-9.

Yeung CK, Teo LH, Xiang LH, Chan HH. A community-based epidemiological study of

acne vulgaris in Hong Kong adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:104-7.

Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 1999;41:577-80.

Stern RS. The prevalence of acne on the basis of physical examination. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 1992;26:931-5.

Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, Cantrell WC, Wang W, Foster KW, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-9.

Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults:

results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.

2001;15:541-5.

Drno B. Recent data on epidemiology of acne. Ann Dermatol Venereol.

2010;137:S49-51

Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of

acne in high school pupils: a community-based study. J Invest Dermatol.

2009;129:2136-41

Law MP, Chuh AA, Lee A, Molinari N. Acne prevalence and beyond: acne disability

and its predictive factors among Chinese late adolescents in Hong Kong. Clin Exp

Dermatol. 2010;35:16-21.

Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Utilization of physician offices by adolescents in the United

States. Pediatrics. 1999;104:35-42.

Stern RS. Acne therapy. Medication use and sources of care in office-based practice. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:776-80.

17. Purvis D, Robinson E, Watson P.. Acne prevalence in secondary school students and

their perceived difficulty in accessing acne treatment. N Z Med J. 2004;117:U1018.

18. Stathakis V, Kilkenny M, Marks R. Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the

community. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:115-23.

19. Schmitt JV, Masuda PY, Miot HA. Acne in women: clinical patterns in different agegroups. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:349-54.

20. Rademaker M, Garioch JJ, Simpson NB. Acne in school children: no longer a concern for dermatologists. Br Med J. 1989;298:1217-9.

21. Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, Dreno B, Finlay A, Leyden JJ, et al. Management of

acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 2003;49:S1-37.

22. Bagatin E, Kamamoto CS, Guadanhim LR, Sanudo A, Dias MC, Barraviera IM, et al.

Prevalence of acne vulgaris in patients with Down syndrome. Dermatology.

2010;220:333-9.

23. Dreno B, Poli F. Epidemiology of acne. Dermatology. 2003;206:7-10.

24. Daniel F, Dreno B, Poli F, Auffret N, Beylot C, Bodokh I, et al. Descriptive epidemiological study of acne on scholar pupils in France during autumn. Ann Dermatol

Venereol. 2000;127:273-8.

25. Friedlander SF, Eichenfield LF, Fowler JF Jr, Fried RG, Levy ML, Webster GF. Acne epidemiology and pathophysiology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:2-4.

26. Del Rosso JQ, Bikowski JB, Baum E, Smith J, Hawkes S, Benes V, et al. A closer look

at truncal acne vulgaris: prevalence, severity, and clinical significance. J Drugs

Dermatol. 2007;6:597-600.

27. Laczynski CM, Cestari S da C. Prevalence of dermatosis in scholars in the region of

ABC paulista. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:469-76.

MAILING ADDRESS:

Denise Loureno Timpano

Rua Borges Lagoa, 508

Vila Clementino

04038-000 - So Paulo - SP

Brazil

E-mail: denise_timpano@yahoo.com.br

How to cite this article: Bagatin E, Timpano DL, Guadanhim LRS, Nogueira VMA, Terzian LR, Steiner D, Florez

M. Acne vulgaris: prevalence and clinical forms in adolescents from Sao Paulo, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol.

2014;89(3):428-35.

An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):428-35.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Social Determinants of Health and Knowledge About Hiv/Aids Transmission Among AdolescentsDe la EverandSocial Determinants of Health and Knowledge About Hiv/Aids Transmission Among AdolescentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eglobal, 6413iDocument15 paginiEglobal, 6413iinsanofaksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors for Childhood TuberculosisDocument5 paginiRisk Factors for Childhood TuberculosisAnthony Huaman MedinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Downloaded From Uva-Dare, The Institutional Repository of The University of Amsterdam (Uva)Document28 paginiDownloaded From Uva-Dare, The Institutional Repository of The University of Amsterdam (Uva)Indah Putri permatasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- vaz2011Document7 paginivaz2011MonicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Autism Congress Analyzes ASD Prevalence Research in EuropeDocument12 paginiAutism Congress Analyzes ASD Prevalence Research in EuropeMarieta Díez-JuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suji. Y. I Year M.Sc. Nursing Masood College of Nursing Bikarnakatta, Kulshekar Post, MANGALORE-575005Document15 paginiSuji. Y. I Year M.Sc. Nursing Masood College of Nursing Bikarnakatta, Kulshekar Post, MANGALORE-575005pavinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors for Dengue Incidence in Brazilian PreschoolersDocument5 paginiRisk Factors for Dengue Incidence in Brazilian PreschoolersAsri RachmawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Students Enrolled in Health Related Courses at Saint Louis University Towards Human Papillomavirus (Philippines)Document8 paginiKnowledge, Attitude and Practices of Students Enrolled in Health Related Courses at Saint Louis University Towards Human Papillomavirus (Philippines)Alexander DeckerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Are Mental Health Problems and Depression Associated With Bruxism in ChildrenDocument12 paginiAre Mental Health Problems and Depression Associated With Bruxism in ChildrenAhmad Ulil AlbabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stunting and Soil-Transmitted-Helminth Infections Among School-Age Pupils in Rural Areas of Southern ChinaDocument6 paginiStunting and Soil-Transmitted-Helminth Infections Among School-Age Pupils in Rural Areas of Southern ChinaRohit GehiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Pone 0258219Document14 paginiJournal Pone 0258219liasarieriwan05Încă nu există evaluări

- Macedo 2010 Risk Factors For Type Diabetes Mel PDFDocument7 paginiMacedo 2010 Risk Factors For Type Diabetes Mel PDFZayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes Prevention Knowledge and Perception of Risk AmongDocument7 paginiDiabetes Prevention Knowledge and Perception of Risk AmongMuhammad AgussalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leprosy Among Children Under 15 Years of Age: Literature ReviewDocument8 paginiLeprosy Among Children Under 15 Years of Age: Literature ReviewCecep HermawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Systematic Review of The Epidemiology of Acne Vulgaris: Anna Hwee Sing Heng & Fook Tim ChewDocument29 paginiSystematic Review of The Epidemiology of Acne Vulgaris: Anna Hwee Sing Heng & Fook Tim ChewRita MantovanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leprosy in Children Under 15 Years of Age in Brazil: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument13 paginiLeprosy in Children Under 15 Years of Age in Brazil: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureThadira RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identify Etiology of Morbidity Events of Earlier Children Among Multigravida Women.Document11 paginiIdentify Etiology of Morbidity Events of Earlier Children Among Multigravida Women.snehal DharmadhikariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lepra Pada AnakDocument5 paginiLepra Pada AnakAdrian AldrinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge On Acne Vulgaris and Menstrual Cycle: A Study On Adolescent GirlsDocument8 paginiKnowledge On Acne Vulgaris and Menstrual Cycle: A Study On Adolescent GirlsChristina WiyaniputriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Significant Oral Cancer Risk Associated With Low Socioeconomic StatusDocument2 paginiSignificant Oral Cancer Risk Associated With Low Socioeconomic StatusWJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incidence of Plasmodium Infections and Determinant Factors Among Febrile Children in A District of Northwest Ethiopia A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument18 paginiIncidence of Plasmodium Infections and Determinant Factors Among Febrile Children in A District of Northwest Ethiopia A Cross-Sectional StudyMegbaruÎncă nu există evaluări

- EhrenkraDocument9 paginiEhrenkraedwingiancarlo5912Încă nu există evaluări

- Level of Awareness and Attitude of Grade 12 GAS Students On Selected Sexually Transmitted Diseases Quantitative Research ProposalDocument37 paginiLevel of Awareness and Attitude of Grade 12 GAS Students On Selected Sexually Transmitted Diseases Quantitative Research ProposalCharlz HizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Epidemiological Profile of Vitiligo in Children and AdolescentsDocument3 paginiClinical Epidemiological Profile of Vitiligo in Children and AdolescentsKarla KaluaÎncă nu există evaluări

- JurnalDocument18 paginiJurnalEry ShaffaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutritional Status of School-Aged Children in Buenos AiresDocument9 paginiNutritional Status of School-Aged Children in Buenos AiresFlori GeorgianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Factors Associated With Acute Diarrhea Among Children Under Five Years of Age in Derashe District, Southern EthiopiaDocument10 paginiEnvironmental Factors Associated With Acute Diarrhea Among Children Under Five Years of Age in Derashe District, Southern Ethiopiadefitri sariningtyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Super Final Output (For Hardbound)Document108 paginiSuper Final Output (For Hardbound)Melody Kaye MonsantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigating Key Determinants of Childhood Diarrheal Incidence Among Patients at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western UgandaDocument14 paginiInvestigating Key Determinants of Childhood Diarrheal Incidence Among Patients at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internal Assesment For Caribbean StudiesDocument20 paginiInternal Assesment For Caribbean StudiesBrandonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Sociodemographic Factors On Febrile Convulsion PrevalenceDocument6 paginiEffects of Sociodemographic Factors On Febrile Convulsion PrevalenceNur UlayatilmiladiyyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level of Knowledge and Evaluation of Perceptions Regarding Pediatric Diabetes Among Greek TeachersDocument25 paginiLevel of Knowledge and Evaluation of Perceptions Regarding Pediatric Diabetes Among Greek Teachers1130223060Încă nu există evaluări

- Ijrtsat 3 1 3Document9 paginiIjrtsat 3 1 3STATPERSON PUBLISHING CORPORATIONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Socioeconomic Risk Markers of LeprosyDocument20 paginiSocioeconomic Risk Markers of LeprosyRobert ThiodorusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.Document9 paginiEpidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.marioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gingival Disease in Adolescents Related To Puberal Stages and Nutritional StatusDocument6 paginiGingival Disease in Adolescents Related To Puberal Stages and Nutritional StatusRosa WeilerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review On Infant Mortality RateDocument4 paginiLiterature Review On Infant Mortality Rateaflsjfmwh100% (1)

- Journal of Pediatric Nursing: MSC, MSC, MSC, BSC, BSCDocument6 paginiJournal of Pediatric Nursing: MSC, MSC, MSC, BSC, BSCClaudia BuheliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stunting, Prevalence, Associated Factors, Wondo Genet, EthiopiaDocument14 paginiStunting, Prevalence, Associated Factors, Wondo Genet, EthiopiaJecko BageurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daft Arp Us TakaDocument12 paginiDaft Arp Us TakaAnonymous bHeH00uobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research ProposalDocument45 paginiResearch ProposalCasey Jon VeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictors of StuntingDocument12 paginiPredictors of Stuntingrezky_tdÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIV/AIDS Awareness Evaluation in The Junior and Senior High School Students of University of The East Caloocan (UEC)Document11 paginiHIV/AIDS Awareness Evaluation in The Junior and Senior High School Students of University of The East Caloocan (UEC)Sebastian Miguel CarlosÎncă nu există evaluări

- ROL FinalDocument28 paginiROL FinalSiyona BansodeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review: Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Paediatrics: J. Nguyen, K. Kotilea, V.Y. Miendje Deyi, P. BontemsDocument8 paginiReview: Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Paediatrics: J. Nguyen, K. Kotilea, V.Y. Miendje Deyi, P. Bontemsps piasÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Rates of Undiagnosed Leprosy and Subclinical Infection Amongst School Children in The Amazon RegionDocument8 paginiHigh Rates of Undiagnosed Leprosy and Subclinical Infection Amongst School Children in The Amazon RegionMedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Childhood psoriasis literature reviewDocument9 paginiChildhood psoriasis literature reviewFranciscus BuwanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Prevalence of Obesity Among School-Aged Children in VietnamDocument7 paginiThe Prevalence of Obesity Among School-Aged Children in VietnamE192Rahmania N. SabitahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lister, 2015Document7 paginiLister, 2015Bianca HlepcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing Child Growth and Developmental DelaysDocument34 paginiFactors Influencing Child Growth and Developmental DelaysJablack Angola MugabeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Socioeconomic Position and Childhood-Adolescent Weight Status in Rich Countries A Systematic Review, 1990-2013.Document15 paginiSocioeconomic Position and Childhood-Adolescent Weight Status in Rich Countries A Systematic Review, 1990-2013.StephanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Childhood Psoriasis: A Review of Onset, Presentation and TreatmentDocument8 paginiChildhood Psoriasis: A Review of Onset, Presentation and TreatmentyuriskamaydaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Perinatal HIV Infection On Older School-Aged Children's and Adolescents' Receptive Language and Word Recognition SkillsDocument9 paginiThe Impact of Perinatal HIV Infection On Older School-Aged Children's and Adolescents' Receptive Language and Word Recognition SkillsAndrew MoriartyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevalence and Evolution of Cases of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescents in BrazilDocument13 paginiPrevalence and Evolution of Cases of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescents in BrazilADRIANA CUNHA VARGAS TOMAZÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIVAIDS-related Knowledge and Behavior Among School-AttendingDocument11 paginiHIVAIDS-related Knowledge and Behavior Among School-Attendingcarmen lopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scabies Among Children in EthiopiaDocument9 paginiScabies Among Children in EthiopiaIJPHSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors For Pregnancy Among Adolescent Girls in Ecuador's Amazon Basin: A Case-Control StudyDocument8 paginiRisk Factors For Pregnancy Among Adolescent Girls in Ecuador's Amazon Basin: A Case-Control StudyJose Carlos Romero SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge and Awareness On Hiv-Aids of Senior High School Students Towards An Enhanced Reproductive Health Education ProgramDocument20 paginiKnowledge and Awareness On Hiv-Aids of Senior High School Students Towards An Enhanced Reproductive Health Education ProgramGlobal Research and Development ServicesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Surgical Management of Tongue Carcinoma - A Clinical Retrospective Research Over A 12 Years PeriodDocument8 paginiModern Surgical Management of Tongue Carcinoma - A Clinical Retrospective Research Over A 12 Years PeriodAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Relationship Between Snoring and LeftDocument8 paginiThe Relationship Between Snoring and LeftAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 paginăDaftar PustakaAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Profile and Survival of Tongue Cancer Patients in "Dharmais" Cancer Hospital, JakartaDocument5 paginiProfile and Survival of Tongue Cancer Patients in "Dharmais" Cancer Hospital, JakartaAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne VulgarisDocument8 paginiAcne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne Vulgaris Acne VulgarisEga JayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11.av HywelDocument12 pagini11.av HywelAlyani Akramah Basar100% (1)

- Short-Term Efficacy of Intravitreal Dobesilate inDocument5 paginiShort-Term Efficacy of Intravitreal Dobesilate inAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Age and Radiation Treatment On Function of Extrinsic Tongue MusclesDocument15 paginiEffects of Age and Radiation Treatment On Function of Extrinsic Tongue MusclesAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tipping Point Tamoxifen Toxicity, Central SerousDocument6 paginiThe Tipping Point Tamoxifen Toxicity, Central SerousAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Associated With Fear of Falling in PeopleDocument7 paginiFactors Associated With Fear of Falling in PeopleAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advances in Treating Central Serous ChorioretinopathyDocument9 paginiAdvances in Treating Central Serous ChorioretinopathyAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment of CondilomaDocument4 paginiTreatment of CondilomaAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short-Term Efficacy of Intravitreal Dobesilate inDocument5 paginiShort-Term Efficacy of Intravitreal Dobesilate inAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kjo 26 260Document5 paginiKjo 26 260Alyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timed Up & Go As A Measure For LongitudinalDocument7 paginiTimed Up & Go As A Measure For LongitudinalAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.nerve Growth Factor For Bell's PalsyDocument6 pagini1.nerve Growth Factor For Bell's PalsyAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Medical MicrobiologyDocument8 paginiJournal of Medical Microbiologybianti nurainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiologi AnogenitalDocument18 paginiEpidemiologi AnogenitalAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcome in Patients With BacterialDocument6 paginiOutcome in Patients With BacterialAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiologi AnogenitalDocument18 paginiEpidemiologi AnogenitalAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Copd 2 273Document10 paginiCopd 2 273zano_adamÎncă nu există evaluări

- ATS GuidelinesDocument46 paginiATS Guidelinesapi-3847280100% (1)

- Res Lounge Anemia of PrematurityDocument10 paginiRes Lounge Anemia of PrematurityAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.nerve Growth Factor For Bell's PalsyDocument6 pagini1.nerve Growth Factor For Bell's PalsyAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steroid-Antivirals Treatment Versus Steroids Alone For The Treatment of Bell's PalsyDocument9 paginiSteroid-Antivirals Treatment Versus Steroids Alone For The Treatment of Bell's PalsyAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S002838431400139X MainDocument10 pagini1 s2.0 S002838431400139X MainAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fourth Step in The World HealthDocument8 paginiThe Fourth Step in The World HealthAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- NNNNNDocument11 paginiNNNNNAlyani Akramah BasarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiologi Hiv AidsDocument3 paginiEpidemiologi Hiv AidsZathisaSabilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Videocon ProjectDocument54 paginiVideocon ProjectDeepak AryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EINC ChecklistDocument3 paginiEINC ChecklistMARK JEFTE BRIONESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical Source Author Date of The Event Objective of The Event Persons Involved Main ArgumentDocument5 paginiHistorical Source Author Date of The Event Objective of The Event Persons Involved Main ArgumentMark Saldie RoncesvallesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.7.3 Lab Use Steganography To Hide Data Answer KeyDocument3 pagini2.7.3 Lab Use Steganography To Hide Data Answer KeyVivek GaonkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digitrip 520Document40 paginiDigitrip 520HACÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bahasa InggrisDocument8 paginiBahasa InggrisArintaChairaniBanurea33% (3)

- Echt Er Nacht 2014Document8 paginiEcht Er Nacht 2014JamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- F&B Data Analyst Portfolio ProjectDocument12 paginiF&B Data Analyst Portfolio ProjectTom HollandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self ReflectivityDocument7 paginiSelf ReflectivityJoseph Jajo100% (1)

- Business Plan1Document38 paginiBusiness Plan1Gwendolyn PansoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeremy Hughes ReviewDocument5 paginiJeremy Hughes ReviewgracecavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complimentary JournalDocument58 paginiComplimentary JournalMcKey ZoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- S 212 Pre Course WorkDocument5 paginiS 212 Pre Course Workafiwierot100% (2)

- Measures of CentralityDocument13 paginiMeasures of CentralityPRAGASM PROGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electronics Foundations - Basic CircuitsDocument20 paginiElectronics Foundations - Basic Circuitsccorp0089Încă nu există evaluări

- Indian ChronologyDocument467 paginiIndian ChronologyModa Sattva100% (4)

- Rock Laboratory PricelistDocument1 paginăRock Laboratory PricelistHerbakti Dimas PerdanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management and Breeding of Game BirdsDocument18 paginiManagement and Breeding of Game BirdsAgustinNachoAnzóateguiÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Japa Retreat NotebookDocument48 paginiNew Japa Retreat NotebookRob ElingsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy 090819Document30 paginiAnatomy 090819Vaishnavi GourabathiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Primavera Inspire For Sap: Increased Profitability Through Superior TransparencyDocument4 paginiPrimavera Inspire For Sap: Increased Profitability Through Superior TransparencyAnbu ManoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment in Southeast AsiaDocument17 paginiAssessment in Southeast AsiathuckhuyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEHC DICOM Conformance CentricityRadiologyRA600 V6 1 DCM 1030 001 Rev6 1 1Document73 paginiGEHC DICOM Conformance CentricityRadiologyRA600 V6 1 DCM 1030 001 Rev6 1 1mrzdravko15Încă nu există evaluări

- Topic1 Whole NumberDocument22 paginiTopic1 Whole NumberDayang Siti AishahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 2Document4 paginiAssignment 2maxamed0% (1)

- Non Deterministic Finite AutomataDocument30 paginiNon Deterministic Finite AutomataAnikÎncă nu există evaluări

- D2DDocument2 paginiD2Dgurjit20Încă nu există evaluări

- Professional Builder - Agosto 2014Document32 paginiProfessional Builder - Agosto 2014ValÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts9 q4 Mod1 Theatricalforms v5Document30 paginiArts9 q4 Mod1 Theatricalforms v5Harold RicafortÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Daily Tar Heel For September 18, 2012Document8 paginiThe Daily Tar Heel For September 18, 2012The Daily Tar HeelÎncă nu există evaluări