Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Încărcat de

Émän HâmzáDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Încărcat de

Émän HâmzáDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Critical Review of Dead-Reckoning from the 21st Dynasty

Author(s): Graham Hagens

Source: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 33 (1996), pp. 153-163

Published by: American Research Center in Egypt

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40000612

Accessed: 21-01-2016 21:24 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Research Center in Egypt is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the

American Research Center in Egypt.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A Critical Review of Dead-Reckoning

from the 21st Dynasty

Graham Hagens

Introduction

In spite of recent advancesin scholarship,absolute dating of the Late Bronze Age (LBA)remains poorly defined. There also seems to be a

problem of lacunae in the records. "InSyriathe

12th and 11th centuries B.C. following the destruction of many Late Bronze Age sites like

Ugaritand RasIbn Hani, has long been regarded

as something of a DarkAge, supposedlylike that

In

in other areasof the eastern Mediterranean."1

an attempt to explain various anomalies in the

historical records, James et al. have suggested a

radicalreduction of the LBAby some 250 years.2

While the proposal faces almost insurmountable

barriers,3the extent to which a more modest reduction would ameliorate these problems has

not yet received attention. Such revised dating

would not be unacceptable in disciplines as varied as Aegean,4Sicilian,5and Cypriot6studies.

The determination of absolute dates is difficult. Radiocarbon dating in the 3000-3500 bp

range is unsatisfactory.7Dendrochronology has

yielded excellent results from the Hallstat era,

and promising progress in the linking of some

European and Near Eastern artifacts,8but the

1 W.G. Dever, BASOR288 (1992), 19.

2 P.

James, I. J. Thorpe, N. Kokkinos, R. Morkot and

ofDarkness(London, 1991).

J. Frankish,Centuries

6 Reviewedin

CAJ1:2 (1991), 227-53.

4 A.

Snodgrass,CA/1:2(1991), 247.

5 R.

Leighton, CA/3:2(1993), 271-83.

6 R. S. Merrillees,BASOR288 (1992), 47-52.

7B. Kemp, CAJ1:2 (1991), 243-44; Merrillees BASOR

288, 51 "radiocarbondates are invokedif they supporta particularhypothesis. . . and dismissedif they do not."

8 P. I. Kuniholmand C. L. Striker, Field

14

J.

Archaeology

(1987), 385-98, and P.I. KuniholmProceedings

of the12thSymposium on Excavation, Researchand Archeometry(Ankara, 1991).

paucity of remains has prevented firm connections being made9. The use of dendrochronology to establish absolute dates in the LBANear

East still remains a 'hope.'10Near Eastern synchronisms in the LBAare also unreliable. "The

chronological reconstruction of [Bronze Age

Cyprus] is essentially informed guesswork and

should be treated accordingly."11

Although the

lists

are

used

to

support LBA

Babylonian king

cannot

be used to

the

data

alone

chronology,

calculate absolute dates.12WesternAsiaticanalyses often reveal a "dangerousreliance on damaged texts of questionable reconstruction" as

chronological linchpins.13The gap in the Assyrian records after the death of TukultiNinurta I

9 L.

Sperber, Untersuchungenzur chronologieder Urnenfeldkultur im nordlichenAlpenvorland von der Schweizbis Oberoster-

reichAntiquas,Reihe 3, 4th Ser, Band 29. (Bonn, 1987).

10A Sherratand S. Sherrat,

CAJ1:2 (1991), 247-53.

11Merrillees,BASOR288, 48.

E. F.Wenteand C. van Siclen in Studiesin Honorof George

R. Hughes,eds. J. Johnson and E. F.Wente.Studiesin Ancient

OrientalCivilization,34 (Chicago,1976), 247-50 refer to the

evidence that Kara-indash,KurigalzuI, Kadashman-EnlilI

and Burna-BuriashII were contemporariesof AmenhotepIII

and IV Earlierhoweverthey note "Inview of the uncertainties still surroundingan absolutechronologyof WesternAsia,

synchronismsbetweenEgyptand the rest of the ancient Near

East had best be excluded from immediate consideration

[until] the chronologyof the New Kingdomhas been reconstructed on the basis of Egyptianevidence alone." (Studies,

219). In a similarvein Brinkmanwrites:"Babylonianchronology, in its present state of uncertaintyis not a reliable standardagainstwhich to measureother chronologiesof the late

second millennium."(J. A. Brinkman,Bibliotheca

Orientalist!

(1970), 307). See alsoJ. A. Brinkman,MaterialsandStudies

for

KassiteHistory(Oriental Institute of the Univ. of Chicago,

1976), 15, n. 28 concerning the identificationof the kings

referredto in the El Amarnaletters.

13W.A. Ward,BASOR288 (1992), 54.

153

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

154

JARCEXXXIII (1996)

late in the 13th century also limits the value of

this resource for LBAsynchronisms.14

Near Eastern chronology still fundamentally

depends on Egypt.15Sothic dating, however,not

only has limited accuracy,16but there is now reason to believe that the important Ebers papyrus

cannot be used as a fixed benchmark.17Deadreckoning of Egyptian regnal years remains the

most important technique for establishing absolute dates. "Sothicor Siriusmode dating ... is

notthe basisfor Egyptianchronology for the New

Kingdom or Late Period. But it is a tool in trying to refine dates obtained by dead-reckoning

of regnal years."18In light of the importance of

this process, a detailed critiqueof this methodology is essential. In this article I will re-examine

the conventionalinterpretationof evidence from

the 21st and 22nd dynasties. The commencement of the 22nd dynastyis reasonablywell fixed

to ca. 945 b.c.e. by historical synchronisms.19

Prior to that the lowest acceptable Sothic date

for the accession of Ramesses II, 1279 b.c.e.,

requires a length of 125-30 years for the 21st

dynasty. This limitation has affected the interpretationof the datafrom this period.20If Sothic

dating is invalid, then the evidence can be subjected to a more objectiveanalysis.I will attempt

to show that the availabledata is indeed ambiguous enough that it cannot be used to confirm the

accepted Sothic dates. When the various uncertainties are taken into account, I will conclude

that dead reckoning cannot supportan accession

date for RamessesII higher than ca. 1200 b.c.e.

14 A. K.

Grayson, Assyrian Royal Inscriptions,Vol 1 (Wiesbaden, 1972), 132-53; also James, Centuries(1991), 268-73,

304-8.

15 K. A. Kitchen, in

High, Middle or Low>?Acts of an International Colloquiumon AbsoluteChronologyheld at the Universityof

Gothenburg,Aug. 1987, ed. P. Astrom, III (Gothenburg: 1987),

I, 37-55 and III, 152-59.

16 See Ward, BASOR288, 53-66.

17 W Helck, in

High, Middle or Low?Acts of an International

Colloquiumon AbsoluteChronologyheldat the Universityof Gothenburg,Aug. 1987, ed. P. Astrom, III (Gothenburg: 1987), 41.

18 K. A. Kitchen,

CAJ1:2 (1991), 237.

19 Ward, BASOR288, 55.

20 For

example K. A. Kitchen, The ThirdIntermediatePeriod

inEgypt (1100-650 B.C.) (Warminster, 1986) (hereafter TIP),

532-33.

While the primarypurpose of this paper is not

to revise the history of the period, the easiest

way to test the process is in fact to propose and

defend an alternate history.This will be done in

two parts dealing respectively with the beginning and the end of the 21st dynasty.In the first

half I will argue that excess years have been assigned to ephemeral pharaohs at the beginning

of the dynasty,and in the second I will present

the evidence for overlap between the 21st and

22nd dynasties.The suggestion that these dynasties may have overlappedis not new, it was made

21

by Lieblein as long ago as 1914, and more re22and Dodson.23

cently by James

Reviewof the History 21st Dynasty

The 21st or Tanite dynasty has been summarized by a number of authors,24and Bierbrier

has examined the family relationships in the

period.25It is one of those epochs which is particularlypoorly illuminated: "Withthe advent of

DynastyXXI the copious sources of information

available in the previous two dynasties vanish.

Administrativepapyri and ostraca prove practically non-existent. Votivestatuarywould seem to

disappearalmost totally.Graffitiand inscriptions

decline to a few badly preserved examples."26

The flood of information reappearsin the 22nd

dynasty.

One of the most important tools used to

study this period is the collection of bandageepigraphsfrom the burial cache at Deir el Bahri.

By comparing these bandages with monumental

inscriptions, rationalizationof the 125-30 years

required for Sothic dating, can be realized.27

The Manethonic records also give 130 years for

the length of the dynasty,but this may be a co21

J. Lieblein, Recherchessur VHistoireet la civilization de

VancienneEgypte(Leipzig, 1914).

22

James, Centuries,256-59.

23 A.

Dodson,/A 79 (1993), 267-68.

24 A. Gardiner,

Egyptof thePharaohs (London, 1961), 30334; J. Cerny CAH3,II/2, 643-57 and TIP.

25 M. L. Bierbrier, TheLate New

KingdominEgypt (c. 1300664 B.C.) (Warminster: 1975).

26 Bierbrier, Late New

Kingdom,45.

2 W. Barta,

Mitteilungen des DeutschenArchdologischenInstituts, Abteilung Kairo 37 (1981), 35-39; TIP, 531.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF DEAD-RECKONING FROM THE 2 1ST DYNASTY

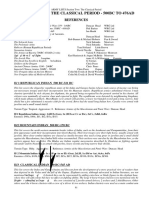

Table 1.

155

Generally Accepted Chronology of the 21st Dynasty

Dynasty Year

Pharaonic Year

I

4

6

9

10

II

12

13

15

16

18

20

21

25

27 AMENEMNISU

30

31 PSUSENNES

36

37

38

49

60

70

78

79

1

4

6

9

10

11

12

13

15

16

18

20

21

25

1

4

1

6

7

8

19

30

40

48

48

References

Yr 1

Yr 4

Yr 6

Yr 9

Year 10

Yr 11

Yr 12

Yr 13

Yr 15

Yr 16

Yr 18

Yr 20

Yr 21

Yr 25

On mummy of Nodjmet reference to HP Pinubjem

Tomb graffito refers to Scribe Butehamun1

Four refs to HP Pinubjem and Scribe Butehamun

Linen by HP Pinubjem on mummy

Four references (linen and graffiti) HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

Four graffiti references to Scribe Butehamun and Pinubjem

Three references including HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

Two references mention HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

HP Pinubjem brings Ramesses III

Two references: HP Masaharta, Pinubjem and son of Butehamun

HP Masaharta

Two graffiti references to son of Butehamun and workmen

Graffito, coming of scribe Nebhepet

Two inscriptional references to Menkheperre

Yr <5

HP Menkheperre seeks oracle concerning exiles2

Yr 6

Yr 7

Yr 8

Yr 19

Yr 30

Yr 40

Yr 48

[Year x of]

Linen by HP Menkheperre on Sethos

Two references to burying and osirifying; agent not named

Two references; King Pinubjem commanded to osirify

Day of inspection (no agent named)

Linen by Menkheperre? (name missing)

Inspection of temples under HP Menkheperre

Three references to HP Menkheperre on linen, stela and burial

King Amenemope, year 49 [of King Psusennes?]

1Butehamen references could

apply to RenaissanceEra.

2Yeardate lost. Could be Amenemnisuor Psusennes.

incidence.28Manethosis "completelyunreliable"

in the 22nd dynasty.29

The accepted chronology of the first part of

the dynasty,with references to key documents, is

shown in Table 1. There are problems with this

chronology. For a start there are fewer generations than would be expected; for example the

descendants of High Priest (HP) Bakenkhons

produced six or seven generations from Sethos II

28

J. Cerny in CAH3II/2, 646: "Manetho'stotal of 130

years. . . bridgestolerablywell the gap between the death of

RamessesXI and the accession of Shoshenq I. Individually,

however,Manetho'sfiguresdisagreewith the scantydates of

the documents."

29 TIP,448-51. On the

unreliabilityof Manetho see also

Ward,BASOR288, 54.

to RamessesX, a period of about 90 years,but the

125 years from the end of dynasty20 to the beginning of the 22nd appearto be bridged by only

three or four.30There is also an absence of Apis

burials.Although this could simplybe due to bad

luck, with burialsyet to be found,31cumulatively

the missing evidence increases the burden on

the rest of the data to supportthe supposednumber of years. The humid climate and "unsettled

times"are usuallyblamed for the poor documentation, but the evidence is inconsistent. Pharaoh

Psusennes I is quite well represented, as is Siamun, but very little of the other five Tanite pharaohs survives.

30 Bierbrier, Late Nezu

Kingdom,16.

31 TIP, 236.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

156

JARCE XXXIII

Proposed Revision of the First

Half of the Dynasty

The

founder

of the dynasty, Smendes, or

who

Nesubanebdjed,

purportedly reigned some

is

twentysix years,

conspicuous by his absence.

In the tale of Wenamun he is described as governor of northern Egypt during the Renaissance Era, but this document is of questionable

historical value.32 Beyond that only two monuments without year dates and a canopic jar

record his name.33 The Memphite genealogies

which list seven generations of priests and their

contemporary kings are of little help in the quest

for Smendes. Pharaohs Amenemnisu

(four year

reign), Psusennes I (three references over fortynine years) and Siamun (ninteen years) are mentioned, but not the dynasty's founder.34 There is

also significant variation in the quantity of material which has survived from one year to the

next. Thus twenty-nine inscriptions are associated with Smendes' twenty-six years, but only nine

for the half century of Amenemnisu

and Psusennes I. A conspicuous gap is observed between

Psusennes' years 30 and 40. Although on the surface this would appear to provide support for

Smendes, in fact these assignments are based

on certain assumptions. I will show below that if

assignations are changed, the variability is considerably reduced.

The claim that Smendes reigned for twentysix years is based on the interpretation of just

four first hand sources, none of which mentions

him by name:

(1) On the Maunier or "Banishment Stela,"

HP Menkheperre

sought the oracle of Amun.

The year date has been lost, but from the small

space occupied it is believed to have been less

than 5. Since Menkheperre became high priest

in year 25 of an unnamed pharaoh, and since

Manetho assigns twenty-six years to Smendes, it

is argued that the twenty-five refers to Smendes,

and the small number to a successor, either

Amenemnisu or Psusennes I.

32Wenamunis considered to be historical K. Kitchen

by

in TIP,250-52, J. Cerny in CAH3,635-43 and A. Egberts,

JEA 77 (1991) 57-67, but see G. Lefebvre,Romansat contes

(Paris,1949), 204-20.

egyptiens

33 TIP,255-57.

34 TIP,187-88, 487.

(1996)

(2) A bandage on the mummy of Sethos I

reads: "Year 6: linen made by HP of Amun

Menkheperre." As above it is argued that this

refers to Psusennes I. From the same mummy

two other bandages without agent being named

read: "Year 7: Day of burying Sethos I" and "Year

7: Day of osirifying Princess and Queen-Ahmose

Sitkamose."

"Year 8: King Pinub(3) A bandage-epigraph:

I

commanded

to

jem

osirify Ahmose I." Since

assumed

the

title "king" in a Year 16,

Pinubjem

Year 8 cannot refer to the same pharaoh. The first

must be Smendes and the second Psusennes I.

"Year I: King Pinub(4) A bandage-epigraph:

I

commanded

to

jem

osirify Prince Siamun." As

for (3).

If any reasonable alternative can be found to

the assumption that the unknown pharaoh was

Smendes, then all the first hand evidence for

that first quarter century would be eliminated.

The solution may be found in considering the career of the High Priest who became a co-regent

of Psusennes, Pinubjem I. Pinubjem succeeded

his father Piankh as HP at Thebes near the start

of the dynasty.35 In Year 16, of an unnamed pharaoh he adopted the title King and appointed

a son Masaharta High Priest. In Year 25 Masaharta was replaced by Menkheperre who enjoyed

a lengthy pontificate. Pinubjem I later assumed

full pharaonic titles which were widely recognized throughout Egypt. Evidence for a period

of co-regency of Pinubjem and Psusennes is

provided by some blocks from Tanis on which

their cartouches have been inscribed. They were

probably also related, and several genealogies

have been proposed. That which most reasonably explains the fact that Psusennes adopted a

Ramesses name, depicts the two as step-brothers

by marriage.36 Pinubjem I was buried in western Thebes with pharaonic pomp and splendor

which was long remembered by descendants. I

suggest that the unnamed pharaoh in the bandage epigraphs was not Smendes but High Priest

and King, Pinubjem I. To test this hypothesis the

following assumptions are made:

35Coveredin

CernyCAH3,646-54; TIP,257-62, 473-75,

536-38.

36With Psusennes a son of Smendes

by one wife and

Pinubjemson-in-lawof Smendesby another.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF DEAD -RECKONING

Table 2.

Dynasty

Year

Pharaonic

Year

1 SMENDES

4

6 AMENEMNISU

10 PSUSENNES

15

18

19

20

21

22

24

25

27

28

29

30

34

39

40 PINUBJEM

42 CO-REGENT

46

47

48 PINUBJEM

49 DIES

57

58

59 AMENEMOPE 1

1

4

1

1

6

9

10

11

12

13

15

16

18

19

20

21

25

30

31

33

37

38

39

40

48

49

Yr 1

Yr 4

FROM THE 2 1ST DYNASTY

157

Alternate Chronology for the Early 21st Dynasty

Year

b.c.e.

References

On mummy of Nodjmet ref. to HP Pinubjem1

Tomb graffito refers to Scribe Butehamun1' 2

Yr 6

Yr9

Yr 10

Yr 11

Yr 12

Yr 13

Yr 15

Yr 16

Yr 18

Yr 19

Yr 20

Yr 21

Yr 25

Yr 30

Four refs. to HP Pinubjem and Scribe Butehamun2

Linen by HP Pinubjem on Mummy

Four refs. to HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

Four graffiti refs. to Scribe Butehamun and Pinubjem

Three refs. to HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

Two refs. mention HP Pinubjem and Butehamun

HP Pinubjem brings Ramesses III

Two refs.: Masaharta, Pinubjem and son of Butehamun

HP Masaharta

Day of inspection (no agent named)

Two graffiti refs to son of Butehamun and workmen

Graffito, coming of scribe Nebhepet

Two inscriptional refs. to Menkheperre

Linen by Menkheperre? (name missing)

Hypothesis: Pinubjem claims pharaonic titles and years

Yr <5

HP Menkheperre seeks oracle concerning exiles

Yr 6

Linen by HP Menkheperre on Sethos

Yr 7

Two refs. to burying; agent not named

Yr 8

Two refs.; King Pinubjem commanded to osirify

Yr 40

Inspection of temples under HP Menkheperre

Yr 48

Three refs. to HP Menkheperre on linen and stela

[Year x of] King Amenemope, year 49 [King Psusennes?]

1010

1007

1005

1001

996

993

992

991

990

989

987

986

984

983

982

981

977

972

971

969

965

964

963

962

954

953

Alternately could be Amenemnisuor Psusennes.

2Butehamunreferences could refer to RenaissanceEra.

(1) That the reign of Smendes was less than

26 years. The exact number is not essential for

the argument, a reign until year 5 is assumed.3

(2) That Pinubjem I was accorded his own

regnal years during his last years, specifically between Years 30 and 40 of Psusennes, arguably

the period of the co-regency.

(3) Therefore years 6, 9, 10 etc. up to 30 of

HP Pinubjem, refer to Psusennes not Smendes,

and years l-5(?), 6, 7 and 8 associated with HP

and King Pinubjem I refer to

Menkheperre

Pinubjem I. After Pinubjem's death, years 40

37An

argumentfor choosing5 is thatthiswouldbe the date

if Manetho'stwenty-sixyearsareemended to sixteen,withthe

count startingwith the RenaissanceEra;cf. TIP,17-18.

and 48 once again apply to Psusennes. The reof the historical data reflecting

arrangement

this hypothesis is shown in Table 2.

Some Consequences

There are no conflicts with other evidence for

the period, instead some of the data becomes

easier to interpret:

1) A difficulty relating to the death of Pinubjem's grandmother Nodgmet is alleviated. A

drawing in Luxor reveals HP Pinubjem wishing

long life to Nodjmet, but a bandage from her

mummy refers to a Year 1 associated with Pinubjem. Since Pinubjem succeeded to the pontificate near the start of the dynasty, conventional

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

158

JARCE XXXIII

chronology demands a very short time between

Pinubjem wishing his grandmother well and her

burial in year I.38 If Year 1 refers either to Amenemnisu or Psusennes, the period between well

wishing and burial is extended to five to nine

years.

2) Alternately the hypothesis allows an extension in Piankh's reign, since the Year 1 on which

Pinubjem officiated could refer to Amenemnisu

or Psusennes in Years 6 or 10 of the new dynasty.

3) The conventional chronology has a fortyeight year pontificate for Menkheperre. While

this is not impossible, it would now be reduced

to a more comfortable twenty-three years.

4) Menkheperre who died shortly before Psusennes, assumed use of the pharaonic cartouche

towards the end of his life.39 According to this

proposal this would have been in his final 8 years,

after the death of his father. The crux of this

hypothesis is that king Pinubjem I was accorded

his own regnal years for a period of time. There

is general agreement that Pinubjem did not enjoy independent reign in Tanis,40 but the details

of his co-regency with Psusennes are quite unknown. The assignation of regnal years to a later

has been used as the

co-regent, Amenemope,

basis of an argument to explain an otherwise

anomalous linen fragment.41

The Second Half of the Dynasty

According to the accepted chronology, four

Tanite pharaohs followed Psusennes for a total of

fifty years: Amenemope (9 years),42 Osochor (6),

Siamun (19) and Psusennes II (14/15 years).43

On the death of Psusennes II power is said to

have shifted from Tanis to Bubastis where the

first pharaoh of the 22nd dynasty, Shoshenq I

took the throne ca. 945 b.c.e.44 I suggest that the

38 TIP,41-43.

39 Bierbrier,LateNew

49.

Kingdom,

J. von Beckerath, Tanisund Theben(Gliickstadt-Hamburg-New York, 1951); Cerny CAH3,647-48 and E. F.

Wente,JNES,26 (1967), 155.

41 TIP,28-30, 531.

42 Gardiner,

Egypt,324; TIP,272.

43 TIP,3-39.

44 "No earlier than 948 B.C.but

possibly as late as 929

B.C."Wenteand van Siclen, Studies,224.

(1996)

at hand is better interpreted by assuming overlap between the end of the 21st and the

beginning of the 22nd dynasties, under the following conditions:

(1) Amenemope's

reign was no

independent

than

2-3

longer

years.

(2) Osochor was probably a member of the

Bubastite dynasty, mistakenly included by Manetho with the Tanites.

(3) Shoshenq I became leading chief of the

Bubastite clan during the reign of Siamun and

began counting regnal years around Year 6 of

Siamun.

(4) The last pharaoh of the dynasty, Psusennes II, was no more than a shadow during

the latter half of Shoshenq's reign.

(5) When Psusennes II became pharaoh his

successor as High Priest was Iuput, son of Shoshenq I. The revised chronology which emerges

from these assumptions is shown in Table 3.

evidence

Discussion

The length of the reign of Psusennes Fs

immediate successor is unclear. Acceptance of

Manetho's nine years for Amenemope demands

between

an unknown period of co-regency

and

Psusennes

and/or

Osochor.45

Amenemope

Our complete ignorance of the nature of this

arrangement dictates that other apparently firm

dates must be called into question. For this reason the Year 5 of Amenemope found in a book

of the Dead46 cannot be used to conclude that

he enjoyed five independent

regnal years. The

little

records

throw

light on the length

priestly

of his reign. While bandage-epigraphs reveal that

was contemporary with two High

Amenemope

Priests (Smendes II and Pinubjem II), the pontificate of Smendes II seems to have been quite

short.47 Some bandages from burials of Theban

with High priest

clergy associate Amenemope

but

those

of

II,

Pinubjem

Pinubjem II with year

dates 1-7 do not name the pharaoh.48 Other

45Because of different

bandages which read "[Yearx of

Psusennes] Year49 of Amenemope,"and "year[x] + 3 of

Amenemope,"TIP,421.

6 A. W. Shorter,

Catalogueof EgyptianReligiousPapyriin the

BritishMuseum, /(1938), 7.

47 TIP, 271.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF DEAD-RECKONING FROM THE 2 1ST DYNASTY

159

Table 3. Alternate Chronology of the Late 21st Dynasty

Tanite

Pharaoh

Psusennes

Amenemope

Siamun

Psusennes II

Year

HP Thebes

HP Memphis

48

49

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Menkheperre

SmendesII

"

II

Pinubjem

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Psusennes II

"

"

"

"

"

"

Pipi-B

"

"

"

"

17

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Iuput

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

evidence suggesting a short reign derives from

two bandage-epigraphsfound on a mummy at

Deir el Bahri. One reads: "Year1,"and the other

"made by Menkheperre in Year 48" [of Psusennes] .49Since linen was usuallymanufactured

shortlybefore its use, this implies a regnal Year1

shortlyafter Psusennes' death (ca. Year49). But

48 TIP,273.

49

77P,421.

AshakhetB

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Ankhefensekhmet

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Shedsunefertem

"

"

"

Bubastite

Pharaoh

Osochor

"

"

"

"

"

Shoshenql

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"11

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

"

Osorkon

"

"

b.c.e.

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

953

952

951

950

949

948

947

946

945

944

943

942

941

940

939

938

937

936

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

1

2

3

935

934

933

932

931

930

929

928

927

926

925

924

923

922

921

if Amenemope was alreadyaccorded co-regency

year-datesthis must refer one of his successors,

Osochor or Siamun.Finallythe Memphite genealogies which mention Psusennes I and Siamun

as contemporaries of High priest Pipi-B ignore

Amenemope (and Osochor). I suggest that no

more than 2-3 years of independent reign can

realisticallybe assigned to Amenemope.

Pharaoh Osochor is reported by Manetho to

have held the throne for six years, but the only

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

160

JARCEXXXIII (1996)

first hand reference is a damaged inscription interpretationof the evidence: the Year13 would

refer to Shoshenq I; Istemkheb C would have

referringto his second year.50There is no vestige

of his presence at Tanis, and his Libyan name

been alive eleven years after the death of Pinub(Osorkon) suggests that he may have belonged jem II, rather than twenty, and the deaths of

to the Bubastite family.51He may have been an

Nesitanebetasheru and Djedptahefankh would

uncle of Shoshenq I.52 In Table 3 Osochor is

have occurredwithin 2 yearsof each other rather

shownas preceding Shoshenq,but from the point

than 15. This revision also clarifies the 22nd

of view of chronology the question is almost irdynastic characteristics of Nesitanebetasheru's

relevant, since no more than two years of his

coffin, since the cultural shift would have taken

are

attested.

if

It

is

to

note

that

reign

interesting

place by that time.

HP Pinubjem II was succeeded by his son HP

Osochor did enjoy a six year chieftainship, this

that

Bubastite

was

first

Psusennes

II, of whose activities little is known.

chronology suggests

power

realized shortlyafter the death of Psusennes I.

On the death of Siamun the new pharaoh was

Siamun is one of the best-known pharaohs of

also named PsusennesII. Twopieces of evidence

the 21st dynasty and much evidence of his achave fueled a debate that these may have been

tivities at Tanis and elsewhere has survived.53 different individuals(PsusennesII and TIP). The

Manetho gives him nine years,a numberwhich is

firstargument,based on the reading of names on

emended

to

nineteen

on

the

basis

of

an

an inscription,has recentlybeen refuted by Dodgenerally

to

a

Year

17.54

For

the

son who showedthat the second name wasprobainscription referring

purof

it

is

to

use

valid

bly that of Shoshenq I.57The second is a piece of

pose

dead-reckoning

only

these attested 17 years.

linen referringto a Year5 during the pontificate

HP

the

successor

to

Smendes

of PsusennesII. Since Psusennes II became high

II,

II,

Pinubjem

is well known from copious epigraphs found at

Priest in Siamun's 10th year, it is argued that

Deir el Bahri where he was buried in Siamun's another Psusennes must have been involved.58I

10thYear.That collection has also yielded impor- propose that Year5 refers to Shoshenq I rather

tant information about his family relationships. than Siamun, thus removing the need for PsuHe had twowives,IstemkhebC and NesikhonsA.

sennes III. This also places a lower limit on ShoIt appears that the marriage to his second wife

shenq'saccessionby positioning his 5th year after

Siamun's 10th, which is reflected in the Table

Nesikhons was short, and that Istemkheb outlived them both. A bandage from the burial of a

above. The discoveryof the names of these phaof

and

Nesitaneraohs

on the same inscription supports this sugNesikhons,

daughter Pinubjem

betasheru, reads: "linen made by ... Istemkheb, gestion.59 Little is known of the activities of

in Year 13."55While this Year 13 could refer to

PharaohPsusennesII. With no building worksor

Siamun, Niwinskipoints out that the burial style decorations, nor mention in the genealogies, he

is typical of the early 22nd dynasty.He argues is "the merest shadow upon the stage of histhat Istemkheb outlived Pinubjem II by 20 years tory."60Not even his burial has been found. I

and that the burial took place during the reign

suggest that by the time of Siamun'sdeath Shoof Psusennes II.56He also mentions that Nesishenq was alreadythe dominant authorityin the

tanebetasheruwasprobablya wife of Djedptahef- land, at which time Psusennes II moved to Tanis

ankh who died in year 11 of Shoshenq I. My and faded to obscurity.We know virtuallynothrevised chronology allows a more comfortable ing about HP PsusennesII'sdeputies and successors in Thebes. The next attested High Priestwas

50 E.

Young,JARCE2(1963), 99-101.

Iuput, a son of Shoshenq I. I suggest that Iuput

51 Gardiner,

Egypt,323.

was

the direct successorto HP Psusennes II.

52

J. Yoyotte, Bulletin de la Societefrangaise d'Egyptologie77-

78 (1977), 39-54.

53 TIP,275-83.

54 On the basisof an

inscriptionfrom Year17. J. Cernyin

CAH311/2,647.

55 TIP,64.

56A.

Niwinski,/EA74 (1988), 226-30.

57

Dodson,/A 79, 267-68.

58 TIP,11-12.

59

Dodson,/A79, 268.

60 TIP,283-84.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF DEAD-RECKONING

Other Evidence

A number of marriages between the Tanite

and Bubastite families are recorded. Maatkare B

daughter of Psusennes II married Osorkon I, son

of Shoshenq I,61 and another daughter of Psusennes II, Tentsepeh B, married the priest Shedsunefertem, who served under Shoshenq.62 This

same priest also married a sister of Shoshenq.

These relationships are more easily accommodated by the chronology I propose. Conventional

dating requires a separation of two generations

between Psusennes II and Osorkon I, with the latter coming to power forty-eight years after Psusennes II first assumed office. My revision reduces

the time between the accession of Psusennes II

and Osorkon I to twenty years. None of this

conflicts with other evidence. Studies of other

officials of the period make it unlikely that there

was a great age difference between Psusennes II

and Shoshenq.63

A dedication

stela at Abydos records that

Shoshenq petitioned Amun asking to be associated with the pharaoh in the victory festivals; an

important step in Shoshenq's rise to power. It is

generally assumed that the pharaoh was Psusennes II.64 This, however, is not expressly stated,

and it may equally be assumed that it was Siamun.

Very little is known of Shoshenq's early years.

His famous campaign in Palestine took place

near the end of his life. This obscurity is more

easily understood if Siamun was on the throne

in Tanis for the first eleven years that Shoshenq

was aspiring to power (and counting) in Bubastis.

It is not known where Shoshenq established his

seat of power. Members of his family built at

Bubastis, and although his descendants settled at

Tanis, there is no sign of his presence there.65

There is thus no conflict with the suggestion that

he established his power-base in Bubastis while

Siamun and Psusennes II were still on the throne

in Tanis. There may have been rivalry between

Shoshenq and the reigning pharaoh: a fragment

from the priestly annals reads "Regnal Year 2 of

61 TIP,60.

62 TIP, 115-16.

63 Bierbrier, Late New

Kingdom,47.

64 TIP, 285-86.

65 D. B. Redford, Pharaonic

King-Lists, Annals and DayBooks (Mississauga, 1986), 309.

FROM THE 21ST DYNASTY

161

the Great Chief of the Ma, Shoshenq justified."

His name, given without cartouche, has an alien

determinative.66 While this may reveal slow acceptance of Shoshenq by the priesthood after the

death of Psusennes II, it could equally refer to resistance to the claims of this upstart Libyan during the reign of Siamun.

Priests and Burials

The genealogy of High Priests in Memphis

provides information of one of the only two families known to have bridged the 20th and 22nd

dynasties.67 Seven generations covered the period: Ashakhet A (contemporary with Amenemnisu) , Pipi-A and Harsiese-J (Psusennes I) , Pipi-B

(over the reigns of Psusennes I and Siamun),

the last

and Shedsunefertem,

Ankhefensekhmet,

being attested under Shoshenq I.68 Since in this

revised chronology only 6 years separate the accession date of Shoshenq and Siamun, it is perof priests

tinent to ask how four generations

could have served these two pharaohs. This can

be explained if Pipi-B's office ended near the

beginning of Siamun's reign while that of Shedsunefertem began near the end of Shoshenq's.

Ashakhet A was probably either appointed or

If the

died during the reign of Amenemnisu.

would have spanned

latter, three generations

the fifty to fifty-five years which separated the

reigns of Amenemnisu and Siamun. The average

of seventeen years per generation indicates a

succession of aged priests.69 This leaves two genfor

erations (Ashakhet B and Ankhefensekhmet)

the twenty-eight years of the reigns of Siamun

and Shoshenq I, or fourteen years each. This is

only one possibility: as Bierbrier points out, the

list itself was drawn up over a century after the

event, and could easily be in error.70

HP Iuput son of Shoshenq I, is attested in

Years 5, 10, and 11 on burial bandages of a third

priest of Amun, "King's Son of Ramesses" Djedptahefankh.71 Because this mummy was found

66 TIP, 288.

67 Bierbrier, Late New

Kingdom,45.

68 TIP, 115.

69 Bierbrier, Late New

Kingdom,48.

70 Bierbrier, Late New Kingdom,48.

71 TIP, 289.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JARCEXXXIII (1996)

162

in the royal tomb at Deir el Bahri which had

been sealed in Siamun's 10th year, it has been

necessary to accept that the tomb was opened

35 years after its closure with no reason other

than to admit this single priest.72This revised

chronology allowsa simpler explanation. If Shoshenq's 11th year corresponded to Siamun'slast,

Iuput could have been appointed High Priest in

the year Djedptahefankhdied. The new dynastic

authorities might have welcomed the opportunity to open the tomb with the excuse of burying a priest with Ramessideconnections.

The induction of the priest Nespaneferhor is

recorded in the priestlyannals of Karnakin Year

2 of Osochor, and that of his son Hori in Year17

of Siamun.The next entry gives a Year13.73This

information can be more easily accommodated

if the second pharaoh was Shoshenq I rather

than Psusennes II. Conventionallyabout twenty

years separates the dates of the two inductions:

this number would be reduced to fifteen. In a

similar manner the gap between the latter two

entries would be reduced from fifteen years

(Siamun's 17th year to Psusennes II's 13th) to

two (Siamun's17th to Shoshenq's 13th).

The shabtis and Osiris figures found in the

burial caches at Deir el Bahri are another source

of information about the dynasty.This revised

chronology simplifies the complex relationships

between the figuresand the mummieswithwhich

they are associated.A couple of examples should

suffice:the shabtisfound with Masahartaburied

by conventional chronology ca 1030-1020 b.c.e.

around Year25 of Smendes, are of a type otherwise unknownbefore the reign of Amenemope.74

As discussed above I suggest that the pharaoh

under whom Masahartaserved was not Smendes

but Psusennes I. Using this revised chronology

Masahartawould have died ca. 980 b.c.e., and

Amenemope's reign would be ca. 955 b.c.e. The

gap between the date of burial and shabti style is

thus reduced from about forty to twenty-five

years. Another example concerns the common

TypeIC Osirisfigures found in the second cache

at Deir el Bahri which are associated with indi72 Gardiner,

Egypt,320; TIP, 289.

15 TIP, 203.

74 D. A. Aston,

JEA 74 (1991) 97.

vidualsburied by conventional dating over a 6585 year period. These include HenttawyB (mid

reign Psusennes) and Djedptahefankh.75The revised chronology reduces the lifetime of this figure type to about 35-45 years, without creating

conflict withvariationsin style during the period.

Conclusions

In this article I have argued that the standard

interpretationof the data from the 21st dynasty

is not incontrovertible. The evidence is better

served if the unknown pharaoh found in the references from the first part of the dynasty was

not Smendes but Pinubjem I. The alternate

chronology illustratedin Table 2 suggests a five

year reign for Smendes, and four for Amenemnisu, but logically the reigns of both Smendes

and Amenemnisucould be reduced to zero without affecting the outcome; in fact the distribution of epigraphs would look even better with

fewer gaps. The 21st dynasty could have been

founded by Amenemnisu, who might even have

come to power during the RenaissanceEra (except for a mention in the Memphite genealogies, Amenemnisu is unattested). It follows that

the actual period separating the mention of

Smendes by Wenamunand the accession of Psusennes to the throne is largelyguesswork.

In the second half of the dynastyI conclude

that the assumption of overlap between the 21st

and 22nd dynasties improves our understanding of the period. More specificallya best fit of

the data is obtained if the first year of Shoshenq I was contemporarywith Siamun'sYear6.

Since the length of Amenemope's reign may

have been no more than a couple of years, the

length of the dynasty after the death of Psusennes I could easily have been just eight years.

When this reduced dating is combined with the

unsubstantiatedyears earlier in the dynasty,it is

concluded that dead reckoning cannot support

a date for the end of the 20th dynasty higher

than about 1000 b.c.e. When in addition the

seventeen year spread between high and low

estimatesof the 19th and 20th dynastiesis taken

75 Aston

(1991), 102.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CRITICALREVIEWOF DEAD-RECKONINGFROMTHE 2 1ST DYNASTY

into account,76 it follows that dead-reckoning

cannot support an accession date for Ramesses

II above about 1200/1190 b.c.e., a century lower

than the conventional "medium"dating.

The objective of this paper has been to illustrate the limitations of the existing evidence. If

76

J. Cernyin CAH3,235-51, 606-16; TIP,533. Its length

cannot easily be extended beyond 211 years to compensate

for a removalof years in the 21st dynasty,since that action

would produce "severaloctogenariansand nonagenarians,"

163

indeed the Ebers papyrus does not provide a

trustworthyanchor, then one may realistically

ask whether the 12th century b.c.e. actuallyexisted. The onus of establishingabsolute dates for

the LBA falls therefore on other dating techniques such as historical synchronismsor archeometry. These may lead in turn to a resolution

of some or all of the troublesome lacunae which

exist in this period of history.

Hamilton, Ontario

Bierbrier, Late New Kingdom,112.

This content downloaded from 41.45.230.38 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 21:24:10 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Casperson - The Lunar Date of Ramesses II - JNES 47-3 1988Document5 paginiCasperson - The Lunar Date of Ramesses II - JNES 47-3 1988AkhesaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Status of Egyptian Chronology - Ward 1992Document15 paginiPresent Status of Egyptian Chronology - Ward 1992goryachev5Încă nu există evaluări

- ROSAPAT 11 Nigro An Absolute Iron Age ChronologyDocument13 paginiROSAPAT 11 Nigro An Absolute Iron Age ChronologyJordi Teixidor AbelendaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhly, J. D. Hittites and Achaeans, Ahhijawa Redomitus.Document18 paginiMuhly, J. D. Hittites and Achaeans, Ahhijawa Redomitus.Yuki AmaterasuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bennet, John. The Structure of The Linear B Administration at Knossos.Document20 paginiBennet, John. The Structure of The Linear B Administration at Knossos.Yuki AmaterasuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFDocument18 paginiHood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFEnzo PitonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lewartowski Cremation and The End of Mycenaean CultureDocument12 paginiLewartowski Cremation and The End of Mycenaean CultureKazimierzÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Arjava, The Mystery Cloud of 536 CE in The Mediterranean Sources, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59 (2005)Document23 paginiA. Arjava, The Mystery Cloud of 536 CE in The Mediterranean Sources, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59 (2005)MicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GenealogicalDocument34 paginiGenealogicalMohamed SabraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Oxford History of The Ancient Near East Volume Iii From The Hyksos To The Late Second Millennium BC Karen Radner Full ChapterDocument68 paginiThe Oxford History of The Ancient Near East Volume Iii From The Hyksos To The Late Second Millennium BC Karen Radner Full Chapterophelia.maciasz118100% (8)

- Moore Documentation FinalDocument5 paginiMoore Documentation FinalMasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. - Third EditionDe la EverandThe End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. - Third EditionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (31)

- And Old Babylonian Periods. (Mcdonald Institute: Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesDocument3 paginiAnd Old Babylonian Periods. (Mcdonald Institute: Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African StudiesSajad AmiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Procopius and DaraDocument20 paginiProcopius and DaraŞahin KılıçÎncă nu există evaluări

- ROSAPAT 11 Nigro 3-Libre PDFDocument13 paginiROSAPAT 11 Nigro 3-Libre PDFfoxeosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramses III and The Sea Peoples - A Structural Analysis of The Medinet Habu InscriptionsDocument33 paginiRamses III and The Sea Peoples - A Structural Analysis of The Medinet Habu InscriptionsScheit SonneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Expulsion of The Hyksos and The End of The Middle Bronze Age: A Reassessment in Light of Recent Chronological ResearchDocument12 paginiThe Expulsion of The Hyksos and The End of The Middle Bronze Age: A Reassessment in Light of Recent Chronological ResearchOktay Eser OrmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A History of Egypt From The 19th To The 30th Dynasties ( (1905) )Document480 paginiA History of Egypt From The 19th To The 30th Dynasties ( (1905) )Lorena Manosalva VergelÎncă nu există evaluări

- VOIGT, M. ., The Chronology of Phrygian GordionDocument24 paginiVOIGT, M. ., The Chronology of Phrygian GordionAngel Carlos Perez AguayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Genizah Letter From Rhodes About CreteDocument13 paginiA Genizah Letter From Rhodes About CreteTobyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impacts of Persian Domination in Late Period EgyptDocument13 paginiThe Impacts of Persian Domination in Late Period EgyptJeremy ReesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mgodoy, Journal Editor, Art01Document16 paginiMgodoy, Journal Editor, Art01Manasseh LukaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Society For The Promotion of Roman StudiesDocument6 paginiSociety For The Promotion of Roman StudiesMiguel Ángel Badal SalvadorÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Greek Martyrium of The NegranitesDocument17 paginiOn The Greek Martyrium of The NegranitesJaffer AbbasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crete GeneralDocument84 paginiCrete GeneralpensiuneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Slave Systems in Their Eastern Mediterranean Context C 800 146 BC David M Lewis Full ChapterDocument67 paginiGreek Slave Systems in Their Eastern Mediterranean Context C 800 146 BC David M Lewis Full Chaptershawn.rankin994100% (4)

- Archaeological Institute of AmericaDocument18 paginiArchaeological Institute of AmericaAjith NarayananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Davis, Aegean PrehistoryDocument59 paginiDavis, Aegean PrehistoryivansuvÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedDe la Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Baud Eg Chronology 144-158Document21 paginiBaud Eg Chronology 144-158Haqi JamisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Revision of Ancient HistoryDocument60 paginiThe Revision of Ancient Historygregoryayca100% (1)

- Graziadio 1991Document39 paginiGraziadio 1991Ronal ArdilesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dating Methods During The Early Hellenistic PeriodDocument8 paginiDating Methods During The Early Hellenistic PeriodFırat COŞKUNÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Aegean and The OrientDocument129 paginiThe Aegean and The OrientUroš MatićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Procopius and DaraDocument20 paginiProcopius and DaraAntigonos80Încă nu există evaluări

- Cassiodorus and The Getica of JordanesDocument19 paginiCassiodorus and The Getica of JordanesthraustilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument15 paginiThe Johns Hopkins University PressSebastien Jones HausserÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeDe la EverandThe Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Forgotten Colony of LindosDocument12 paginiA Forgotten Colony of LindosEffie LattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epaminondas and The Genesis of The Social WarDocument11 paginiEpaminondas and The Genesis of The Social WarpagolargoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Egypt - Ascension of KingDocument20 paginiEgypt - Ascension of KingAmelie LalazeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chronology and Terminology - ManningDocument26 paginiChronology and Terminology - ManningSU CELIKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandars 1993 - Later Aegean Bronze SwordsDocument46 paginiSandars 1993 - Later Aegean Bronze SwordsMaria-Magdalena Stefan100% (1)

- Donald Redford - On The Chronology of The Egyptian Eighteenth DynastDocument13 paginiDonald Redford - On The Chronology of The Egyptian Eighteenth DynastDjatmiko TanuwidjojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palladas and The Age of ConstantineDocument26 paginiPalladas and The Age of ConstantineLuca BenelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamic Astronomical InstrumentsDocument13 paginiIslamic Astronomical InstrumentsrickÎncă nu există evaluări

- Population Roman AlexandriaDocument19 paginiPopulation Roman AlexandriaWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Athanasius Kircher's Universal Polygraphy - George E. McCrakenDocument15 paginiAthanasius Kircher's Universal Polygraphy - George E. McCrakenJohn GajusÎncă nu există evaluări

- JSA 2021 Zanggeretal Cosmic-SymbolismDocument39 paginiJSA 2021 Zanggeretal Cosmic-Symbolismramie sherifÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Babylonian Chronicles and Berossus Robert DrewsDocument18 paginiThe Babylonian Chronicles and Berossus Robert DrewsdrahsanguddeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alicia Simpson, Before and After 1204Document34 paginiAlicia Simpson, Before and After 1204milan_z_vukasinovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alicia Simpson, Before and After 1204 PDFDocument34 paginiAlicia Simpson, Before and After 1204 PDFmilan_z_vukasinovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory and Practice in Late Antique ArchaeologyDocument440 paginiTheory and Practice in Late Antique ArchaeologyFlorea Mihai Stefan100% (6)

- MESKELL, L. 1999. Archaeologies of Life and Death PDFDocument20 paginiMESKELL, L. 1999. Archaeologies of Life and Death PDFmarceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Momiglinao - Ancient History and The Antiquarian PDFDocument32 paginiMomiglinao - Ancient History and The Antiquarian PDFLorenzo BartalesiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Georgios Kardaras - Byzantium and The Avars, 6th-9th Century AD Political, Diplomatic and Cultural RelationsDocument275 paginiGeorgios Kardaras - Byzantium and The Avars, 6th-9th Century AD Political, Diplomatic and Cultural RelationsAnonymous nHtXnn6Încă nu există evaluări

- Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt: Curriculum GuideDocument9 paginiSoulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt: Curriculum GuideÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peer Reviewed Title: Author: Publication Date: Series: Permalink: Additional InfoDocument10 paginiPeer Reviewed Title: Author: Publication Date: Series: Permalink: Additional InfoÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Urk IIIDocument157 paginiUrk IIIÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review:The Physicians of Pharaonic Egypt Paul GhaliounguiDocument5 paginiBook Review:The Physicians of Pharaonic Egypt Paul GhaliounguiÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Names and Relationships of The Royal Family ofDocument14 paginiNames and Relationships of The Royal Family ofÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gardiner Late-Egyptian Miscellanies 1937Document304 paginiGardiner Late-Egyptian Miscellanies 1937Émän Hâmzá100% (7)

- Herihor in Art and Iconography Kingship PDFDocument5 paginiHerihor in Art and Iconography Kingship PDFÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Gender and Identity in Third Inter PDFDocument2 paginiWomen Gender and Identity in Third Inter PDFÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viziers PDFDocument22 paginiViziers PDFÉmän Hâmzá100% (1)

- Ancient Naukratis Excavations at Greek Emporium in Egypt Part II The Excavations at Kom HadidDocument6 paginiAncient Naukratis Excavations at Greek Emporium in Egypt Part II The Excavations at Kom HadidÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- TekDocument16 paginiTekÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Inscriptions On Tombs & Monuments Madras Vol 1 (Cotton)Document264 paginiList of Inscriptions On Tombs & Monuments Madras Vol 1 (Cotton)Émän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Semi-Literacy in Ancient Egypt Some ExaDocument15 paginiSemi-Literacy in Ancient Egypt Some ExaÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal: American Research Center in EgyptDocument20 paginiJournal: American Research Center in EgyptÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Nine Descendants of Pinudjem IDocument32 paginiChapter Nine Descendants of Pinudjem IÉmän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- الفكر السياسي في العراق القديم 181Document4 paginiالفكر السياسي في العراق القديم 181Émän HâmzáÎncă nu există evaluări

- Litany For The Faithful DepartedDocument2 paginiLitany For The Faithful DepartedKiemer Terrence SechicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Roadside StandDocument5 paginiA Roadside Standkshitikaatri121813Încă nu există evaluări

- HZ01 User Manual v1.0Document33 paginiHZ01 User Manual v1.0Johnny DoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabia Expo Participants (ST Petersburg)Document2 paginiArabia Expo Participants (ST Petersburg)Samir SaadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ame1012r OthDocument152 paginiAme1012r OthraganandparappaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Jewish Background of The Battles of Jamal and Siffin PDFDocument27 paginiThe Jewish Background of The Battles of Jamal and Siffin PDFAMEEN AKBAR100% (1)

- IOE Entrance Result 2074 PDFDocument116 paginiIOE Entrance Result 2074 PDFBJ Puri25% (4)

- The Eternal Glory of ChristDocument7 paginiThe Eternal Glory of Christhilbert_garlando1112Încă nu există evaluări

- WWW - Apspsc.gov - in GROUP 4 RESULTS 2012 - Prakasam District Invalid ListDocument36 paginiWWW - Apspsc.gov - in GROUP 4 RESULTS 2012 - Prakasam District Invalid ListReviewKeys.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frank W. Walbank - A Historical Commentary On Polybius, Vol. 1 - Commentary On Books 1-6-Oxford University Press - Clarendon Press (1957) PDFDocument796 paginiFrank W. Walbank - A Historical Commentary On Polybius, Vol. 1 - Commentary On Books 1-6-Oxford University Press - Clarendon Press (1957) PDFGabriel de Carvalho100% (2)

- DBA 3.0 Army Lists Book 2 BetaDocument26 paginiDBA 3.0 Army Lists Book 2 Betababs45190100% (2)

- Hematic Anel CTS: Valuation of Hematic EvelopmentDocument7 paginiHematic Anel CTS: Valuation of Hematic EvelopmentCarlos G. Figueroa NievesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal's LoversDocument19 paginiRizal's LoversPaolo Bautista100% (1)

- Russian Separatism in Crimea and Nato-Elena MizrokhiDocument24 paginiRussian Separatism in Crimea and Nato-Elena MizrokhiNadina PanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brian Tracy - Daily Habits of Successful People - YouTube Video Transcript (Life-Changing-Insights Book 10)Document10 paginiBrian Tracy - Daily Habits of Successful People - YouTube Video Transcript (Life-Changing-Insights Book 10)gaetano confortoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aarav Follow Up SheetDocument170 paginiAarav Follow Up SheetMS InternationalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extra Grammar MaterialDocument1 paginăExtra Grammar MaterialNURÎncă nu există evaluări

- CompositionDocument136 paginiCompositionZlatko Vicković100% (2)

- British Literature (Poetry) - 24433171 - 2024 - 02 - 08 - 14 - 41Document124 paginiBritish Literature (Poetry) - 24433171 - 2024 - 02 - 08 - 14 - 41rajmoprÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book ReviewDocument4 paginiBook ReviewIekzkad RealvillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Literature During The Abbasid PeriodDocument2 paginiArabic Literature During The Abbasid Periodehtishamhaq50% (2)

- LP HMM Abril 2020 P.4Document156 paginiLP HMM Abril 2020 P.4Isaias RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biodata Peserta BTCLS 2019 Per KelasDocument9 paginiBiodata Peserta BTCLS 2019 Per KelasTiyopmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phil LitDocument1 paginăPhil LitJaryll Vhasti P LagumbayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fst-errachudia-Liste Admis Tawjihi Phase5 TawjihnetDocument39 paginiFst-errachudia-Liste Admis Tawjihi Phase5 TawjihnetBakissÎncă nu există evaluări

- S.No Customer Name Cust No Model Ca Name FeedbackDocument8 paginiS.No Customer Name Cust No Model Ca Name FeedbackCR student xerox AvadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cracco Ruggini - Rome in Late Antiquity - Clientship, Urban Topography, and ProsopographyDocument18 paginiCracco Ruggini - Rome in Late Antiquity - Clientship, Urban Topography, and ProsopographyddÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistan Affairs - Important Constitutional Development MCQsDocument7 paginiPakistan Affairs - Important Constitutional Development MCQsTouqeer MetloÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Short History of SaigonDocument5 paginiA Short History of SaigonMie TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mission Vision PDFDocument4 paginiMission Vision PDFJune VillanuevaÎncă nu există evaluări