Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Josie and Cakes Overview Menstrual Cycle2

Încărcat de

robert543Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Josie and Cakes Overview Menstrual Cycle2

Încărcat de

robert543Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Josie and the Cakes

That Saturday, Josie was helping her mum in the kitchen baking cakes. Dad had

taken the others out to the park. Josie enjoyed those moments when she and her mum

were alone together. It made her feel more grown-up and she tried to behave like it.

“I’ll get the eggs out,” she said, and one promptly fell splat on the floor.

Her mother winced quickly, but only said: “Bad luck. Here’s some kitchen

towel.”

“Beth’s mother is having another baby,” remarked Josie. “I wish we could have

another one, too.”

Josie’s mother laughed. “You don’t think that this house is full enough as it is?

Actually, you already have inside you all the eggs you will ever have for your own

future babies. About half a million of them.”

“Half a million?” exclaimed Josie. “But they’d never fit in.”

“If they were as big as these eggs, certainly not. But there is a big difference

between hens and human beings. Birds’ eggs contain all the genetic material, that’s the

instructions to create a new bird, and …”

“The DNA?” interrupted Josie.

“You know a lot, don’t you?

Yes, the DNA. But the bulk of a

hen’s egg isn’t DNA; what we eat is

the food on which a new chick relies

until the moment it hatches. The hen

sits on the egg to keep the chick

warm, but it doesn’t give it more

food. With a human mother, the egg

contains only the mother’s genetic

material. That’s why it can be so

small, minute in fact. All the

nourishment for a new baby is

provided by the mother’s body,

inside her womb, or uterus. Give

Figure 1: Uterus with tubes and ovaries me that paper and I’ll draw you a

1 © Louise Kirk 2009

diagram of what happens each month inside a woman’s body. It will begin happening

to you in the next couple of years or so, probably when you are 12 or 13.”

Josie brought the paper and sat hunched up on a stool. The cake mixture by this

time had long been forgotten. Her mum drew a curious diagram which looked a bit like

a sheep’s head. This she labelled as she spoke.

“All of these organs are right down inside your lower tummy. First of all, you

have two ovaries, one on the left and one on the right. That is where the tiny eggs are

stored. Each month, a chemical messenger is sent by the brain to choose an egg, or two

if there are to be non-identical twins …”

“Or three?” chimed in Josie.

“Or three, but that’s very rare. Anyway, an egg is

chosen from either ovary in any one month, it doesn’t

matter which, and it grows very fast in a protective case

called a follicle. The follicle grows faster than anything

else in the body until it becomes the size of a walnut.”

Josie’s mum drew again to show the enlarged follicle

bursting open to release the egg out of an ovary. “The

follicle itself breaks up inside the ovary while the egg is

caught by the feathery fingers at the end of the fallopian

Figure 2: Fimbria pick up egg tube.” She pointed to what looked like a multi-fingered

hand poised over an ovary and attached to the end of a

long wiggly tube.

Her mum continued: “The egg can’t move anywhere by itself which is why it has

to be picked up by the fimbria. The fimbria introduce it into the top of the tube and

there within half a day or so it will die.

“But now I’m going to tell

you what happens when the egg

is fertilised.” She extended her

drawing to show the egg moving

along the tube and bedding down

in the wall of the utererus.

“How does the egg come

to be fertilised, Mum?” asked

Figure 3: Fertilised egg moves to uterus Josie, looking up at her.

2 © Louise Kirk 2009

“Well, when a man and a woman love each other very much they embrace in a

special way which releases sperm from the man into the woman. The sperm look a bit

like tadpoles, but they are so small you can’t see them except under a microscope. There

are lots and lots of them. Unlike eggs, they have tails and can swim fast up the woman’s

body, looking for a fresh egg. If they find one, lots of sperm crowd round it. One sperm

wins it and unites with it (it seems that the egg chooses that sperm …we don’t quite

know how … from all the ones surrounding it) and the life of a new baby begins.

That’s called fertilisation, or conception, and it happens here, up at the end of the tube

not far from the ovary.

“The fertilised egg is then squeezed along

inside the tube all the way down to the uterus,

where the new nest has been made ready. That

takes about 6 – 9 days. Then it nestles down

inside the wall of the uterus and attaches itself

very firmly. The baby grows and grows and

nine months later it is ready to be born.”

Josie was amazed. “To think all this

happened to make me!”

“Yes” said her mum. “And you see why

you are so unique and so loved? You were made

from a piece of me (my egg, or ovum) and a

piece of Daddy (his sperm) and when you think

Figure 4: Unborn child at 16 weeks of the enormous choice of cells, both ova and

sperm, from which you happened to be made –

an infinite variety – you can see how incredibly unique you are, and your brother and

sister. And yet you all come from the two of us and our love for each other. Most

months, of course, the egg isn’t fertilised.”

“So what happens to all those eggs that don’t make it?” asked Josie.

“Well, most of those half million never actually mature at all. And the ones that

do die inside the tube within 12, or at most 24, hours after being released.”

“It’s amazing, isn’t it?” said Josie. “Those eggs live inside me all those years,

then a lucky one is picked out of the ovary, and it goes and dies twelve hours later.”

“I hadn’t thought of it like that,” her mother replied. “But yes, except for the

really lucky eggs which live to become babies, you are right. The woman’s body does

weep in a way at the death of each egg because, some 11–14 days afterwards, the womb

3 © Louise Kirk 2009

discards its nest, which comes away in the form of drops of blood. It comes away very

gently, a drip or sometimes a clot at a time, lasting about 4 or 7 days, though it varies

with each woman. The uterus is actually made of very strong muscle, and to make the

lining come away it squeezes itself.”

“Can you feel it?” asked Josie

“It can cause a dull ache, or even quite a strong pain in the first day or two. Each

woman is different, but it is nothing to be frightened of.”

“Where does the blood actually come out?” asked Josie.

“It drains down from the uterus

through the cervix, which is the opening

to the womb. It acts like a valve, only

letting in and out what it wants to so that

the womb is protected from germs. Then

it goes through the vagina, which is the

tube which connects the uterus to the

outside of the body. Your bottom

actually has three outlets: one for

spending pennies, one for spending

tuppence, and the third, which is between

them, is the opening of the vagina. That’s

where the blood comes out. It’s also

Figure 5: Lining of the uterus is shed during a period where the husband’s penis goes in during

intercourse, which is the very special

closeness I talked about.”

Josie looked a bit uncomfortable. “That is what they call ‘making love’, right?

Doesn’t that hurt, Mum?”

Her mother smiled at her. “No, because the body is very clever and is made for

this. When a man and woman love each other and have given themselves totally to each

other, intercourse is like a very special cuddle and each of their bodies gets ready for the

other. This is why it is important to be totally in love and committed to each other.

Because if a man forces himself on a woman, or she is afraid, then, yes it can hurt. That

is one reason why rape is a terrible crime. Your vagina and cervix will go on growing

and developing until you’re aged about 19, so before that a girl does not have the full

enjoyment of sex. Premature sex is not the same as the real thing.

4 © Louise Kirk 2009

“As I said when you bleed, or have a period as we call it, the blood drips out quite

slowly, though it can be heavier for some women. There are special pads you wear

inside your knickers and you just change them when you go to the toilet. They’re made

out of material a bit like disposable nappies and are very absorbent.”

At that minute, they were distracted by footsteps outside, and the sound of very

familiar voices.

“Quick, Josie! We haven’t put those cakes in the oven yet.”

“Never mind, Mummy. We have been discussing all sorts of things about eggs.

And there are doughnuts in the cupboard.”

Diagrams with amended captions taken from Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology for the Natural Family Planning

Practitioner, Thomas W. Hilgers, m.d. (Creighton University), 1981 with kind permission of the author.

5 © Louise Kirk 2009

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Free Reading Comprehension Passage 4 Thgrade 3 Rdgrade 5 ThgradeDocument9 paginiFree Reading Comprehension Passage 4 Thgrade 3 Rdgrade 5 ThgradeChristian James JonsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life's Greatest MiracleDocument2 paginiLife's Greatest MiracleJessa Mae Cuenco50% (4)

- Reaction Paper-In The WombDocument3 paginiReaction Paper-In The WombKuya Ericson71% (7)

- Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal InstinctDe la EverandMom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal InstinctEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- Lesson Plan in Menstrual CycleDocument5 paginiLesson Plan in Menstrual CycleCheskaTelanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phases of The Menstrual CycleDocument6 paginiPhases of The Menstrual CycleJuliet C. Clemente100% (1)

- Prenatal DevelopmentDocument37 paginiPrenatal DevelopmentAbegail JanorasÎncă nu există evaluări

- CC8 - Unit 5.3 - CoursebookDocument3 paginiCC8 - Unit 5.3 - CoursebookHuong DoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPEAKING, How Babies Are MadeDocument1 paginăSPEAKING, How Babies Are MadeArdi KendariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 10 DLP - FertilizationDocument11 paginiGrade 10 DLP - FertilizationYvonne CuevasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life in The WombDocument27 paginiLife in The WombAreej ArshadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 8 Science: Reproduction in AnimalsDocument21 paginiClass 8 Science: Reproduction in AnimalsJ CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Mission 8 chp9 Reproduction in AnimalsDocument3 paginiScience Mission 8 chp9 Reproduction in Animalssidharthraj861Încă nu există evaluări

- Good Nights: The Happy Parents' Guide to the Family Bed (and a Peaceful Night's Sleep!)De la EverandGood Nights: The Happy Parents' Guide to the Family Bed (and a Peaceful Night's Sleep!)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (14)

- Uploads1222122210100bc9 Unit1 Topic1 3.PDF 5Document18 paginiUploads1222122210100bc9 Unit1 Topic1 3.PDF 5e33498138Încă nu există evaluări

- Gineco ENGLISHDocument198 paginiGineco ENGLISHVașadi Razvan CristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identify The Letter of The Choice That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionDocument5 paginiIdentify The Letter of The Choice That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionMara LabanderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- AbortionDocument77 paginiAbortionFev BanataoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science: Quarter 2 - Module 3: Modes of Reproduction in AnimalsDocument68 paginiScience: Quarter 2 - Module 3: Modes of Reproduction in AnimalsChester Allan EduriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Before BirthDocument5 paginiLife Before BirthSuelto CharlynÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 4 - Reproduction 1.2Document15 paginiCHAPTER 4 - Reproduction 1.2Halizah RamthanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prenataldevelopment PDFDocument14 paginiPrenataldevelopment PDFAmber TajwerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biology Y7 RevisionDocument9 paginiBiology Y7 RevisionPaleOfficialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary Chap.5 Par.6Document1 paginăSummary Chap.5 Par.6Anouar el OuakiliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructuonal MayerjalDocument5 paginiInstructuonal MayerjalKimberly Anne T. RinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Making of You: The Incredible Journey from Cell to HumanDe la EverandThe Making of You: The Incredible Journey from Cell to HumanÎncă nu există evaluări

- January-The God of ChosenDocument1 paginăJanuary-The God of ChosenJayricDepalobosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ejercicios ReproductionDocument4 paginiEjercicios ReproductioninesÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Happens To The Egg Cell - NotesDocument10 paginiWhat Happens To The Egg Cell - NotesKomalesh TheeranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lifebeforebirth: Consider This Observation by A New York DoctorDocument2 paginiLifebeforebirth: Consider This Observation by A New York DoctorAsida Maronsing DelionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 5 Science-Quarter 2 - Lesson 2 - The Female Reproductive SystemDocument19 paginiGrade 5 Science-Quarter 2 - Lesson 2 - The Female Reproductive SystemJudith MateoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting Started With The Cosmic EggDocument26 paginiGetting Started With The Cosmic EggRaíssa SanasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fetal Period: by DR - Abdallah GreeballahDocument55 paginiThe Fetal Period: by DR - Abdallah GreeballahrawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Lesson: With Teacher Aninda/Feny/Amal /lidaDocument9 paginiScience Lesson: With Teacher Aninda/Feny/Amal /lidaGIS Grade 5AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huma JoshDocument17 paginiHuma JoshBenny AgassiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproductive System QuizDocument3 paginiReproductive System QuizJONEL FONTILLASÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 Scientific SelfDocument15 paginiChapter 2 Scientific Selfbulcasejohn21Încă nu există evaluări

- Echidnas (/ɪ Kɪdnəz/), Sometimes Known As Spiny Anteaters. The FourDocument7 paginiEchidnas (/ɪ Kɪdnəz/), Sometimes Known As Spiny Anteaters. The FourHONLETH ROMBLONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bio CH 4-Repdoduction NewDocument70 paginiBio CH 4-Repdoduction NewAzwan MohammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- S 2 Unit 5 Course Book, Work Book Ques and KeysDocument12 paginiS 2 Unit 5 Course Book, Work Book Ques and KeysHein Aung ZinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproduction in AnimalsDocument3 paginiReproduction in Animalsbinu_praveenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Miracle of LifeDocument6 paginiThe Miracle of LifeKiseKunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reproduccion SexualDocument3 paginiReproduccion SexualLUIS GARCIAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fertilization: Deblina Roy M.Sc. Nursing 1 Year Student K.G.M.U Institute of NursingDocument20 paginiFertilization: Deblina Roy M.Sc. Nursing 1 Year Student K.G.M.U Institute of NursingAngelica SolomonÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Vitro FertilizationDocument30 paginiIn Vitro FertilizationDianna RoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Science 8 & 9 FinalDocument84 paginiIntegrated Science 8 & 9 FinalFrancis ShiliwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Form Biology Tasksheet Topic: Fertilization Week 1: Engage: "KWL"Document2 pagini3 Form Biology Tasksheet Topic: Fertilization Week 1: Engage: "KWL"ZaijahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 PresentationDocument6 paginiChapter 4 PresentationLhekha RaviendranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsDocument4 paginiQuiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsThemis ArtemisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsDocument4 paginiQuiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsHashim OmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsDocument4 paginiQuiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation Graphsrafiqah nasutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsDocument4 paginiQuiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsCamille FrancoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsDocument4 paginiQuiz 9 Human Reproduction Pregnancy Menstruation GraphsHashim OmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal ReproductionDocument3 paginiAnimal ReproductionMysticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science 5 DLP 2 - FetilizationDocument8 paginiScience 5 DLP 2 - FetilizationAldrin PaguiriganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science and Health: FertilizationDocument8 paginiScience and Health: FertilizationPauline Leon-Francisco LeongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catholic Union Event 10 Jan 14Document1 paginăCatholic Union Event 10 Jan 14robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Prayer ProcessionDocument1 paginăPrayer Processionrobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Catholic Ism PosterDocument1 paginăCatholic Ism Posterrobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- March For LifeDocument1 paginăMarch For Liferobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Pri b7b Full PageDocument1 paginăPri b7b Full Pagerobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Prayers For Vigil 2011Document11 paginiPrayers For Vigil 2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Closing Party 2011Document1 paginăClosing Party 2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Instructions For The Prayer VigilaDocument4 paginiInstructions For The Prayer Vigilarobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Halfway Event October 2011Document1 paginăHalfway Event October 2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Human Formation Seminars - Pornography Conflicts 2Document53 paginiHuman Formation Seminars - Pornography Conflicts 2robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Peter ColosiDocument6 paginiPeter Colosirobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Threats To Life at The Earliest Stages (Email Version)Document30 paginiThreats To Life at The Earliest Stages (Email Version)Robert ColquhounÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bulletin Pulpit Sept2011Document1 paginăBulletin Pulpit Sept2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

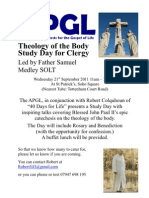

- Theology of The Body Clergy Study DayDocument1 paginăTheology of The Body Clergy Study Dayrobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Letter To Clergy-Autumn2011Document1 paginăLetter To Clergy-Autumn2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- William NewtonDocument4 paginiWilliam Newtonrobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- 40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and RemembranceDocument48 pagini40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and Remembrancerobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Madrid Party 2011Document1 paginăMadrid Party 2011robert543Încă nu există evaluări

- 40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and RemembranceDocument48 pagini40 Days of Prayer For 40 Years of Abortion: A Daily Prayer Guide For Healing, Hope and Remembrancerobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Matthew PintoDocument7 paginiMatthew Pintorobert543Încă nu există evaluări

- Michael WaldsteinDocument6 paginiMichael Waldsteinrobert543100% (1)

- All Levels of The Government Have The Responsibility To Ensure That Adolescent and Youth Populations Enjoy The Highest Attainable Standard of Health and Access To Quality Health Services Including SRHDocument6 paginiAll Levels of The Government Have The Responsibility To Ensure That Adolescent and Youth Populations Enjoy The Highest Attainable Standard of Health and Access To Quality Health Services Including SRHJhon dave SurbanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrative Review of Factors and Interventions That in Uence Early Father - Infant BondingDocument8 paginiIntegrative Review of Factors and Interventions That in Uence Early Father - Infant BondingKhalid AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Youth Sexuality and Pre Mariltal Relationships WebinarDocument8 paginiYouth Sexuality and Pre Mariltal Relationships WebinarNYC VisayasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mode of Delivery and Persistence of Pelvic Girdle Syndrome 6 Months PostpartumDocument20 paginiMode of Delivery and Persistence of Pelvic Girdle Syndrome 6 Months PostpartumDanil ArmandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 21: Gonadal Function: by Marissa GrotzkeDocument21 paginiChapter 21: Gonadal Function: by Marissa GrotzkeJanielle FajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obgyn History Taking and Write UpDocument5 paginiObgyn History Taking and Write UpSarah HamidÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21 Birth Plan Template No Tool Just TemplateDocument8 pagini21 Birth Plan Template No Tool Just TemplateAnn Mekha ShajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extension Folder No-49 PDFDocument2 paginiExtension Folder No-49 PDFRadhika NaiduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Costa Masturbation PDFDocument2 paginiCosta Masturbation PDFBruno Faria CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan - Spontaneous AbortionDocument2 paginiNursing Care Plan - Spontaneous Abortionderic100% (2)

- Data Pending Rs Citra Arafiq 25112018Document20 paginiData Pending Rs Citra Arafiq 25112018Zahirman HamzahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fetal Alcohol SyndromeDocument16 paginiFetal Alcohol Syndromexdaniellecutiex100% (1)

- Kaylee MyersDocument5 paginiKaylee Myersapi-410354384Încă nu există evaluări

- Nama: Nadia Fitra RahmaDocument2 paginiNama: Nadia Fitra RahmaNadya Fitra RahmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mola Hidatidosa JESDocument24 paginiMola Hidatidosa JESmember12dÎncă nu există evaluări

- FCT Family Planning Costed Implementation PlanDocument140 paginiFCT Family Planning Costed Implementation PlanJoachim ChijideÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEX EDU in MalaysiaDocument6 paginiSEX EDU in MalaysiaRashekkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is It Okay To Be Gay?Document6 paginiIs It Okay To Be Gay?A.J. MacDonald, Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Sex TipsDocument85 paginiSex TipsWaleed50% (6)

- Animal Development - : EmbryogenesisDocument45 paginiAnimal Development - : EmbryogenesisRoland Garcia CadavonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bangalore Escorts - Escorts in Bangalore - Bangalore Call GirlsDocument8 paginiBangalore Escorts - Escorts in Bangalore - Bangalore Call GirlsjaanvikohliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex Gender SexualityDocument20 paginiSex Gender SexualityErwin AlemaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Primeras Experiencias Sexuales en Adolescentes Inhaladores de Solventes, de La Genitalidad Al ErotismoDocument14 paginiPrimeras Experiencias Sexuales en Adolescentes Inhaladores de Solventes, de La Genitalidad Al ErotismoIván SaucedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomi Reproduksi WanitaDocument23 paginiAnatomi Reproduksi WanitaocepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Concepts, Development & Classification of TheoryDocument40 paginiBasic Concepts, Development & Classification of TheoryReshmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abruptio Placentae Nursing Quiz: Start StartDocument6 paginiAbruptio Placentae Nursing Quiz: Start StartLot Rosit100% (1)

- IUD Complications: Management Strategies: Learning ObjectivesDocument9 paginiIUD Complications: Management Strategies: Learning ObjectivesIndah Putri permatasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCHN OutlineDocument15 paginiMCHN OutlineAngel Strauss KmpsnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q1 Grade-8-Health-Dll-Week-1Document10 paginiQ1 Grade-8-Health-Dll-Week-1Abby Erero-Escarpe100% (2)