Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Crime Media Culture 2011 Jenks 229 36

Încărcat de

ites76Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Crime Media Culture 2011 Jenks 229 36

Încărcat de

ites76Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

417602

CMCXXX10.1177/1741659011417602JenksCrime Media Culture

Article

The context of an emergent and

enduring concept

Crime Media Culture

7(3) 229236

The Author(s) 2011

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1741659011417602

cmc.sagepub.com

Chris Jenks1

Abstract

This paper seeks to situate the concept of a moral panic within a set of historical and social changes

and thus to demonstrate that its impact and subsequent acceptability within the vocabulary

of sociology were in part due to the conditions of its emergence. Earlier and more positivistic

criminology was unduly committed to the essence of an act, whereas the breakthrough afforded

by Cohen and Youngs idea was to attend to the appearance of an act in an era when image

and representation were becoming primary phenomena within the social sciences. The work

concludes with an analysis of the social construction of transgression.

Keywords

appearance, moral panic, transgression

Let me begin by introducing the two major figures who provided us with our concept, moral

panics, Professor Stanley Cohen and Professor Jock Young. Stan was brought up in South Africa

and graduated from Witwatersrand University, after which he came to the UK to complete a PhD

at the LSE, then take a lectureship at Durham followed by a Chair at Essex. He then moved to

Israel and spent a considerable time as Director of the Institute of Criminology in Jerusalem. Finally

Stan returned to the LSE as Professor of Sociology where he now holds an Emeritus Chair.

Jock started out from a lectureship at Enfield College of Technology, which in the 1970s was

a real powerhouse of radical social theory. Enfield morphed into Middlesex where Jock held his

first Chair, he spent some time in the States where he still has a Chair at City University of New

York (CUNY) and he currently has an associate post at Kent University in the UK.

Both of these people are known to be major contributors to and innovators within modern

criminology and they both have considerable and distinguished lists of publication around the

issue of moral panics but ranging well beyond that now classic idea.

Interestingly and unfortunately, our paths have crossed very little over the years. I have encountered Stan across a public lecture and I met Jock a couple of times through some of my postgraduate

peers who were teaching at Enfield in the early 1970s I do remember that he had a rather

Brunel University, UK

Email: chris.jenks@brunel.ac.uk

1

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

230

CRIME MEDIA CULTURE 7(3)

handsome Pancho Villa moustache and a smart leather shoulder bag but, to be fair, that was

the era when we were all wearing high-heeled boots!

My supervisor, Basil Bernstein, who became known primarily through his socio-linguistic

codes, always said to me if you want to get famous get yourself a concept; by which he meant

that if someone mentions your idea it is as if you walk into the room and occupy some of their

space and time well, I never did, and see what happened to me. These two major theorists, Stan

and Jock, developed a stunning concept which we are still discussing 40 years on. I think it falls to

them to tell us whether this innovation has been an accelerator or a hindrance in their careers, and

its also up to them to tell us which of the two came up with the idea I suspect this is a zone of

some contention and I am not going to step into that water!

Before I start to discuss ideas I have one last question to ask and that is: how should a sociologist respond when the media which they are engaging in their critique take their concepts for

granted and assume them as part of their everyday vocabulary? I have even heard the hectoring

stentor John Humphries invoke moral panic, not in contempt but as a descriptive term the irony

was just staggering.

Now I want to engage with the rise of the moral panic concept and I shall do this by looking at

the social context within which it emerged and how the idea successfully picked up on certain key

elements of the zeitgeist and I mean this to be a laudatory, not a reductionist, exercise.

All sociological analysis takes place in a social and historical context; it is not completely bound

to that context but neither can it wholly liberate itself from that context. It is the bisection of history

and biography that makes for the uniqueness of any sociological act. Sociology is probably no more

than 60 years old in the United Kingdom and in its first decade its preoccupations were substantively around vertical stratification (that is, social class as opposed to race and gender which were

then seen, perversely, as horizontal forms of stratification). The dominant theoretical paradigms of

this earlier work were normative, holistic and, deriving largely from the United States, systemic.

By the early 1970s times were a-changing and criminology and the sociology of education

were two of the most dynamic and critical areas of study in the development of social theory. They

were both fundamentally questioning the normative order and demanding new forms of understanding and mobility. The values that delineated the good and the decent from the bad and

pathological were coming under question. The basic assumptions of positivist criminology were

being subjected to fierce interrogation. Given the overwhelming power of the central values and

the saturation of the socialization process in his social system, Parsons (1951) had difficulty in

accounting for crime at all. Crime had to be reconstructed after the fact as a distortion of or

through the warping of normal dispositions within marginal subcultures. Merton (1968) suggested that theft might be seen as striving for the appropriate ends but applying the inappropriate

means. Earlier, C. Wright Mills (1943) in his typically irreverent and acerbic fashion had argued

that normative criminologists all came from the same small towns, went to the same small universities, married into the same small coterie of faculty wives and consequently had small minds that

disposed them to judge decisively in relation to the morality and criminality of others. But still,

elective courses in Deviancy persisted in the academy in the USA and the UK, and this was not

deviancy in a statistical sense. The course in the Sociology of Deviance which I took in the late

1960s was a somewhat vicarious tour of naughty things done by wicked people; often one sickness a week. I recall being required to write an essay on why homosexuality was dysfunctional and

this was in post-Wolfenden London!

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

Jenks

231

It is said that if you can remember the 1960s then you werent there well, I can remember

the sixties, I seem to have spent most of them taking exams. But alongside this routine practice of

credentialism one was very much aware that there was a mounting tide of criticism in all spheres

of life. Parents were being questioned, politicians interrupted, professors were disagreed with,

war was out of favour, upward mobility was seen as a right, pleasure was integrated into life, living standards rose, more people were getting better educated, there was a greater emphasis on

merit, rights and democracy the standards of the past were no longer good enough, they could

not claim respect through simply being there. Increasingly, and particularly in the academy, nothing was sacred, nothing was to be taken for granted. Perhaps even criminals were people too and

the forces of law and order and indeed the law makers were not simply right, they operated from

positions of interest, but interests that were not articulated.

Whereas the problem of order had been the unproblematic basis of all sociological thinking,

there was now a noticeable shift to questions of control. We were rightly concerned with power

how are boundaries established around phenomena, how are those boundaries policed, and

what is the power hidden behind and protected by the boundaries? This disruptive issue can be

easily formulated in the apparently simple question: if someone tells you something is for your

own good then what is in it for them? even if its your MP, a policeman, your teacher, or even

your parents!

Dependency, symbiosis and reciprocity were ideas waning in their explanatory power, they

were being replaced by questions of fragmentation, conflict and choice. Thus dense, hegemonic

structures were having to concede to forms of agency and forms of identity politics, and this was

challenging stuff. The social order that we were all previously assumed to adhere to and its contracts or obligations that only criminals or deviants were assumed to challenge no longer held

sway. Power made for order, benign or repressive, and agency always threatened to bring that

down.

Finally, I suppose, quasi-ontological issues arose about how the social world comes into being;

is it through the artful day-to-day practices of social actors, through language, or through its positive relation with existing sociological categories? Yet again, all questions of power.

Despite the fact that there were noticeable factions and demarcations between sociologists,

the shared drive towards demystification and reclaiming of the social provided an interesting unified thrust and despite their perspectival differences Marxists, neo-Marxists, phenomenologists,

interactionists, ethnomethodologists and more found things to talk about and we were in the era

of the NEW new directions in sociological theory, new criminology, new sociology of education

and so on.

The new sociologies held a number of epistemological elements in common:

Primarily, that life is seen as project and humankind as the generator of meaning.

Secondly, that although Marxism necessarily retained the constraint that structures bestow,

a greater voluntarism had emerged and a swing away from macro analysis.

Third, an antagonism formed towards quantification (see Cicourel and Kitsuse [1963] and

also Hindess [1973] on official statistics) and even towards the scientific method as itself a

tool of power. Science isnt powerful because its true but true because its powerful

became the mantra. This suited me well because I was bad with numbers and I remember

being berated by John Goldthorpe for soft, sloppy, interpretive work.

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

232

CRIME MEDIA CULTURE 7(3)

Fourth, as already stated, there was a burgeoning mistrust of the taken-for-granted, the

underlying categories that made up the social order (see Bernstein, 1974).

A final element in this liberal stew was the ascendancy of subjectivity, a cult of the individual in theorizing which took many forms but was often dressed as reflexivity, a kind of

critical self-regard for a standpoint. A simpler version of this had been bequeathed by

Becker (1967) when he asked us whose side are you on? and almost universally the

answer came back the underdog this instanced a new, committed morality.

So here you have the receptive conditions for the high impact of moral panic theorizing, though

not exhaustively the spark for its creation. How clear, articulate and disinterested are the central

values that mark out crime? Where does middle-class adolescent high spirits drift into workingclass delinquency; how do we distinguish between pilfering from the factory stores and whitecollar crime; is crime against property different from crime against the person? Typification studies

revealed how categories of people were conflated with categories of action; labelling studies

showed how identity becomes shaped by formal designations; and social reaction studies enabled

us to see how responses to certain actions may be disproportionate but also defining. Dont the

criminalized deserve a chance or at least a voice?

We were no longer interested in the noumenal form of crime but in its phenomenal form; its

appearance, not its essence.

The moral panic thesis touched many of these elements in a sophisticated, critical and pioneering manner. But let us return to our origins once more and investigate the consensus convention in our study and its erosion.

The development of sociology confronted us with the problem of a new reality that is, society

as a thing to be studied, not just to take part in. Experientially, being in society is difficult enough,

but as an object of understanding it has always presented inscrutable difficulties. What then is this

thing called society?

Until the latter third of the last century sociologists were largely content to understand the

social through conceptual vehicles such as order, systems and shared norms and values. Now

these devices served well and enabled us to sustain a feeble idea of society as being rather like the

flat earth with a centre, a cohesive force and strict edges. We talked about normative conduct and

deviant conduct. Increasingly it dawned on us that our simple model was unsupported by life

itself. Society did not rest on an even base; there were folds and subterranean tendrils moving

from part to part. The parts no longer interrelated so easily, there was no obvious harmony or

agreement, but instead competition, difference and divergence.

We now had to resort to other devices such as solidarity, culture and community to express

pockets of agreement and to reaffirm our faith in the collective life. The discipline, having evolved

in part through a competition between theoretical perspectives, shifted through a series of metaparadigms which we regarded sequentially as the linguistic turn, the reflexive turn, the cultural

turn and the visual turn. This macro-conceptual evolution was not just one that was driven by

an individual sense of intellectual purpose. The society itself was moving more and more rapidly

and the zeitgeist was shifting (or adapting) with equal acceleration. The Thatcherism of the 1980s

pronounced the death of the social and cast human relations loose onto the vagaries of market

forces; at the same time the academy erupted into the era of the post-, with post-history, postfeminism, post-colonialism, post-nationalism and overarching them all the spectre of the

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

Jenks

233

postmodern. Tangible metaphors of the social no longer seemed viable and our languages of

order gave way to new geographies of social space, many of which appeared entirely cognitive.

What remained, however, was a lingering, and real, sense of limits. Though diffuse and ill-defined

the limits, the margins, now took on a most important role in describing and defining the centre.

Beyond the limits be they classificatory, theoretical or even moral there remained asociality or

chaos but ever more vivid and in greater proximity. Thus our new topic became the transgression

that transcends the limits or forces through the boundaries.

Apart from the more obvious economic, technological and political changes that had brought

our present circumstances into being, there were also two grand philosophical moments that had

predicted their moral consequences. First the Enlightenment with its insistence on the ultimate

perfectibility of humankind a goal that was to be achieved by privileging calculative reason. And

second, Nietzsches announcement that God is dead.

Now the Enlightenment ideal has meant three things: (1) that we have come to confuse change

with progress; (2) that we have experimented with human excellence through various flawed

political policies; and (3) that we have become intolerant if not incredulous towards excessive or

transgressive behaviour. Nietzsches obituary for the Almighty, on the other hand, has given rise

to three different but contributory processes: (1) it has removed certainty; (2) it has mainstreamed

the re-evaluation of values; and (3) it has released control over infinity (see Jenks, 2003).

Perhaps only 40 years ago we discussed society as a reality with confidence, as recently as

1990 we considered ideas like a common culture without caution. Today, in the wake of a series

of debates we cannot even pronounce such holisms without fear of intellectual reprisals on the

basis of epistemological imperialism. Identity politics has become a new currency with different,

and increasingly minority, groups claiming a right to speak and equivalence of significance.

Perpetually fresh questions are raised about the relationship between the core of social life and

the periphery; the centre and the margins; identity and difference, the normal and the deviant,

and the possible rules that could conceivably bind us into a collectivity. The fragility of the bond

exposed the need or perhaps propensity for groups to externalize clusters of otherness to provide

some passing stability for their own modes of conduct moral panic buttons always in easy reach!

Now these kinds of question have always been raised but in liminal zones within the culture

such as the avant garde, radical political movements (anarchism and situationism), and countercultural traditions in creative practice (surrealism). However, such questions have now moved

from the liminal zones into the centre. Berman (1983) after Marx announced all that which is

solid melts into air; we have all become aware that the centre cannot hold. An insecurity has

entered into our consciousness, an insecurity concerning our relationships with others and concerning the ownership of our own desires. We are no longer sure on what basis we belong to

another being.

Various forms of dependency or, to put the matter less provocatively, trust are fostered by

the reconstruction of day-to-day life via abstract systems. Some such systems, in their global

extensions, have created social influences which no one wholly controls and whose outcomes

are in some part specifically unpredictable. (Giddens, 1991: 176)

This present state of uncertainty and flux within our culture raises fundamental questions concerning the categories of the normal and the pathological when applied to action or social

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

234

CRIME MEDIA CULTURE 7(3)

institutions. Such periods of instability, as we are now experiencing, tend to test and force issues

of authority and tradition truth and surety are up for question. Clearly the 1960s provide another

recent example of such a febrile epoch. The difference in the experience of today with that of the

1960s is that now we cannot commit readily to change because there exists no collective faith in

an alternative to the existing cultural configuration note the almost unremarkable transition

from one government to another in the UK in 1997 and again into a coalition in 2010. It is hard

to be militant in a culture where there is no consolidated belief in any collective form of action or

collective identity; the political right appeals to outmoded ideas of nation (symbolized through

currency or big society) and the left targets minority groupings to create temporary clusterings

(note single-parent families or even students). It would seem that instability and uncertainty are

experienced today in peculiarly privatized forms that rarely extend beyond ourselves or our immediate circle. Far from a fear of freedom, we now appear to espouse a fear of collectivity; we have

become wary of seeking out commonality with others. The vociferous politics of our time are thus

identity politics, and the response to dominant conditions is often poetic. There is a pathos in

witnessing the temporary arousal of an aimless collective consciousness, and then only in the

wake of the sad and untimely death of a dilettante princess I refer to the extended public

mourning of Diana Princess of Wales in the UK in 1997. Perhaps a more constant mechanism to

countered decentredness is economic jingoism (the invading European workforce) and belief stigmatization (anti-semitism and islamophobia) both provide external parameters to buttress a

febrile internality and a floating signifier of moral righteousness the cue for a panic.

It is only by having a strong sense of the together that we can begin to understand and

account for that which is outside, at the margins or, indeed, that which defies the consensus. The

contemporary rebel is left with neither utopianism nor nihilism, but rather loneliness. Time has

already outstripped Camus (1971) and his wholly cognitive rebel:

Metaphysical rebellion is the means by which a man protests against his condition and

against the whole of creation. It is metaphysical because it disputes the ends of man and

creation. The slave protests against the condition of his state of slavery; the metaphysical

rebel protests against the human condition in general. The rebel slave affirms that there is

something in him which will not tolerate the manner in which his master treats him; the

metaphysical rebel declares that he is frustrated by the universe. For both of them it is not

only a problem of pure and simple negation. In fact in both cases we find an assessment of

values in the name of which the rebel refuses to accept the condition in which he finds

himself. (Camus, 1971: 29)

And also the inspirations of the Marquis de Sade, the grand libertine, who saw God as the great

criminal and whose dedicated nihilism asserted that vice and virtue comingle in the grave like

everything else. The possibility of breaking free from moral constraint in contemporary culture

has become an intensely privatized project. As we recognize no bond we acknowledge fracture

only with difficulty how then do we become free-of or different-to? Such questioning provides

the perfect moment to theorize the transgressive conduct that stems from such positionings.

Transgression is that which exceeds boundaries or exceeds limits (see Jenks, 2003). However,

we need to affirm that human experience is the constant experience of limits, perhaps because of

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

Jenks

235

the absolute finitude of death; this is a point made forcefully by Bataille (1985). Constraint is a

constant experience in our action; it needs to be to render us social. Interestingly enough, however, the limits to our experience and the taboos that police them are never simply imposed from

the outside; rather, limits to behaviour are always personal responses to moral imperatives that

stem from the inside. This means that any limit on conduct carries with it an intense relationship

with the desire to transgress that limit. Simple societies expressed this clearly through mythology

and more recent societies have celebrated this magnetic antipathy between order and excess

through periodic carnival and the idea of the world turned upside down, as Bakhtin (1968)

demonstrates.

Let us say a few initial words about the complex nature of carnival laughter. It is, first of all, a

festive laughter. Therefore it is not an individual reaction to some isolated comic event. Carnival

laughter is the laughter of all the people. Second, it is universal in scope; it is directed at all and

everyone, including the carnivals participants. The entire world is seen in its droll aspect, in its

gay relativity. Third, this laughter is ambivalent; it is gay, triumphant, and at the same time

mocking, deriding. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives. Such is the laughter of the

carnival. (Bakhtin, 1968: 1112)

Transgressive behaviour therefore does not deny limits or boundaries; rather it exceeds them

and thus completes them. Every rule, limit, boundary or edge carries with it its own fracture, penetration or impulse to disobey. The transgression is a component of the rule. Seen in this way

excess is not an aberration nor a luxury; it is rather a dynamic force in cultural reproduction it

prevents stagnation by breaking the rule and it ensures stability by reaffirming the rule.

Transgression is not the same as disorder; it opens up chaos and reminds us of the necessity of

order. But the problem remains, we need to know the collective order, to recognize the edges in

order to transcend them. Moral panic devices are that which we employ to provide some temporary state of solidity in an uncertain world. The content of these devices may shift in time from

mods and rockers, to bankers, paedophiles and MPs expenses, but the form and purpose remains

constant. Such devices enable us to cling on to some piece of wreckage, as yet unsunk, to escape

the fluidity that threatens to engulf.

References

Bakhtin, M.M. (1968) Rabelais and His World. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Bataille, G. (1985) Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 19271939. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Becker, H.S. (1967) Whose side are we on? Social Problems 14(Winter): 239247.

Berman, M. (1983) All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. London: Verso.

Bernstein, B. (1974) Sociology and the sociology of education: A brief account. In: Rex, J (Ed.) Approaches to

Sociology. London: Routledge, 145159.

Camus, A. (1971) The Rebel. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Cicourel, A. and Kitsuse, J. (1963) A note on the use of official statistics. Social Problems 11(2): 131139.

Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Oxford: Polity.

Hindess, B. (1973) On the Use of Official Statistics in Sociology. London: Macmillan.

Jenks, C. (2003) Transgression. London: Routledge.

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

236

CRIME MEDIA CULTURE 7(3)

Merton, R. (1968) Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

Mills, C.W. (1943) The professional ideology of social pathologists. American Journal of Sociology 49(2):

165180.

Parsons, T. (1951) The Social System. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com at DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY on December 21, 2014

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Compassionate Temperament: Care and Cruelty in Modern SocietyDe la EverandThe Compassionate Temperament: Care and Cruelty in Modern SocietyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rhetoric of Fallenness in Victorian CultureDe la EverandTainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rhetoric of Fallenness in Victorian CultureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engaging Violence: Civility and the Reach of LiteratureDe la EverandEngaging Violence: Civility and the Reach of LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms EverybodyDe la EverandCynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms EverybodyEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (94)

- Anthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryDe la EverandAnthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsDe la EverandDemocracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- Better Left Unsaid: Victorian Novels, Hays Code Films, and the Benefits of CensorshipDe la EverandBetter Left Unsaid: Victorian Novels, Hays Code Films, and the Benefits of CensorshipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tough Choices: Structured Paternalism and the Landscape of ChoiceDe la EverandTough Choices: Structured Paternalism and the Landscape of ChoiceEvaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (2)

- A Time for the Humanities: Futurity and the Limits of AutonomyDe la EverandA Time for the Humanities: Futurity and the Limits of AutonomyEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (1)

- Bread and Circuses: Theories of Mass Culture As Social DecayDe la EverandBread and Circuses: Theories of Mass Culture As Social DecayEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (5)

- Narrative Criminology: Understanding Stories of CrimeDe la EverandNarrative Criminology: Understanding Stories of CrimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Empire of Conspiracy: The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar AmericaDe la EverandEmpire of Conspiracy: The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond Biofatalism: Human Nature for an Evolving WorldDe la EverandBeyond Biofatalism: Human Nature for an Evolving WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Humanist Science: Values and Ideals in Social InquiryDe la EverandA Humanist Science: Values and Ideals in Social InquiryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and PoliticsDe la EverandMoral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and PoliticsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (47)

- Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsDe la EverandFolkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Crime Media Culture 2011 Young 245 58Document14 paginiCrime Media Culture 2011 Young 245 58ites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free MarketsDe la EverandCapitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free MarketsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Violence in Roman Egypt: A Study in Legal InterpretationDe la EverandViolence in Roman Egypt: A Study in Legal InterpretationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group Works: Art, Politics, and Collective AmbivalenceDe la EverandGroup Works: Art, Politics, and Collective AmbivalenceÎncă nu există evaluări

- After Queer Theory: The Limits of Sexual PoliticsDe la EverandAfter Queer Theory: The Limits of Sexual PoliticsEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (3)

- Engaging Evil: A Moral AnthropologyDe la EverandEngaging Evil: A Moral AnthropologyWilliam C. OlsenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Even When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationDe la EverandEven When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Happened to Civility: The Promise and Failure of Montaigne’s Modern ProjectDe la EverandWhat Happened to Civility: The Promise and Failure of Montaigne’s Modern ProjectÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reconstructing Individualism: A Pragmatic Tradition from Emerson to EllisonDe la EverandReconstructing Individualism: A Pragmatic Tradition from Emerson to EllisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Geometry of Genocide: A Study in Pure SociologyDe la EverandThe Geometry of Genocide: A Study in Pure SociologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cornell '69: Liberalism and the Crisis of the American UniversityDe la EverandCornell '69: Liberalism and the Crisis of the American UniversityÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Multivoiced Body: Society and Communication in the Age of DiversityDe la EverandThe Multivoiced Body: Society and Communication in the Age of DiversityÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Social Imaginary?: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESDe la EverandWhat Is Social Imaginary?: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- Political Peoplehood: The Roles of Values, Interests, and IdentitiesDe la EverandPolitical Peoplehood: The Roles of Values, Interests, and IdentitiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narrating Evil: A Postmetaphysical Theory of Reflective JudgmentDe la EverandNarrating Evil: A Postmetaphysical Theory of Reflective JudgmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Human Difference: Animals, Computers, and the Necessity of Social ScienceDe la EverandThe Human Difference: Animals, Computers, and the Necessity of Social ScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- YOUNG, Jock. Moral Panics and The Transgressive OtherDocument14 paginiYOUNG, Jock. Moral Panics and The Transgressive OtherCarol ColombaroliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marsh Melville Moral Panics and The British Media March 2011Document21 paginiMarsh Melville Moral Panics and The British Media March 2011Saša PerovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subcultural Studies in UK & USDocument22 paginiSubcultural Studies in UK & USTheo CassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociological Explanations of Crime & DevianceDocument18 paginiSociological Explanations of Crime & DevianceJLaaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Officer'S Academy (Noa) SOCIOLOGY, Lecture No. 1 Course Outline As Per FPSCDocument13 paginiNational Officer'S Academy (Noa) SOCIOLOGY, Lecture No. 1 Course Outline As Per FPSCTuba Abrar100% (1)

- Epstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'Document16 paginiEpstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'_Verstehen_Încă nu există evaluări

- Cultures and SubculturesDocument22 paginiCultures and SubculturesTheo CassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contribution To The Development of AnthropologyDocument7 paginiContribution To The Development of AnthropologyRubelyn PatiñoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cine Tracts 1Document69 paginiCine Tracts 1Mauricio FreyreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moral Panic DissertationDocument4 paginiMoral Panic DissertationWriteMyPaperOnlinePasadena100% (1)

- Cultures and Chicago SchoolDocument22 paginiCultures and Chicago SchoolTheo CassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spitzer Horowitz - CritiqueDocument3 paginiSpitzer Horowitz - Critiqueites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Whitewashing Race - Scapegoating CultureDocument38 paginiWhitewashing Race - Scapegoating Cultureites76Încă nu există evaluări

- The Teddy Boy As ScapegoatDocument29 paginiThe Teddy Boy As ScapegoatHambali RamleeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Crucible ProjectDocument5 paginiThe Crucible Projectites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Spitzer Reply - To.horowitzDocument4 paginiSpitzer Reply - To.horowitzites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Victor Moral PanicDocument26 paginiVictor Moral Panicites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Scapegoating in A Time of CrisisDocument7 paginiScapegoating in A Time of Crisisites76Încă nu există evaluări

- ScapegoatingDocument2 paginiScapegoatingites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Spitzer DevianceDocument15 paginiSpitzer Devianceites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Scapegoating - How and Why Scapegoating OccursDocument5 paginiScapegoating - How and Why Scapegoating Occursites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Hunt Moral Panic MediaDocument21 paginiHunt Moral Panic Mediaites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Sociology 2011 Rohloff 634 49Document18 paginiSociology 2011 Rohloff 634 49ites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Scapegoating SkateboardersDocument2 paginiScapegoating Skateboardersites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Moral - Panic.decivilising RohloffDocument12 paginiMoral - Panic.decivilising Rohloffites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Enemies Everywhere: Terrorism, Moral Panic, and Us Civil SocietyDocument24 paginiEnemies Everywhere: Terrorism, Moral Panic, and Us Civil SocietyidownloadbooksforstuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scapegoating and Leader BehaviorDocument9 paginiScapegoating and Leader Behaviorites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Rethinking Moral PanicDocument17 paginiRethinking Moral Panicites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Moral - Panic.decivilising RohloffDocument12 paginiMoral - Panic.decivilising Rohloffites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Luce Moral - Panics JournalismDocument17 paginiLuce Moral - Panics Journalismites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Lafferty Devils AdvocateDocument22 paginiLafferty Devils Advocateites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Husbands Crises - National Id - NewmoralpanicsDocument18 paginiHusbands Crises - National Id - Newmoralpanicsites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Rohloff Extending Moral PanicsDocument18 paginiRohloff Extending Moral Panicsites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Moral Panic Social Theory RohloffDocument18 paginiMoral Panic Social Theory Rohloffites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Hawdon Rhetoric and Moral PanicsDocument27 paginiHawdon Rhetoric and Moral Panicsites76100% (1)

- Herman ClosureDocument13 paginiHerman Closureites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Erich GoodeDocument9 paginiErich Goodeites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Fearessay-20070404 Frank FurediDocument11 paginiFearessay-20070404 Frank FurediOlkan SenemoğluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erikson - Sociology of DevianceDocument8 paginiErikson - Sociology of Devianceites76Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Additional Mathematics SPM PapersDocument2 paginiAnalysis of Additional Mathematics SPM PapersJeremy LingÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05 Preprocessing and Sklearn - SlidesDocument81 pagini05 Preprocessing and Sklearn - SlidesRatneswar SaikiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zhe Agency (SG) Pte LTD: Catherene (Ref: ZA290)Document3 paginiZhe Agency (SG) Pte LTD: Catherene (Ref: ZA290)diandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iex BeginnerDocument22 paginiIex BeginnerNeringa ArlauskienėÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education (IJE)Document2 paginiInternational Journal of Education (IJE)journalijeÎncă nu există evaluări

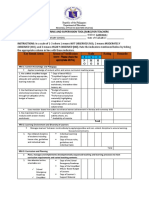

- Monitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersDocument3 paginiMonitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersJhanice Deniega EnconadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Line Officer Accessions BOT HandbookDocument88 paginiLine Officer Accessions BOT HandbookamlamarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes by Pavneet SinghDocument9 paginiNotes by Pavneet Singhdevesh maluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matching Cause and Effect: 1. A. B. C. DDocument2 paginiMatching Cause and Effect: 1. A. B. C. DGLENN SUAREZÎncă nu există evaluări

- SIP Annex 11 - SRC Summary of InformationDocument7 paginiSIP Annex 11 - SRC Summary of InformationShane Favia Lasconia-MacerenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prepare 2 Test 1 Semester 4Document3 paginiPrepare 2 Test 1 Semester 4Ira KorolyovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cae/Cpe Report Blueprint: Step by Step GuideDocument3 paginiCae/Cpe Report Blueprint: Step by Step GuideEvgeniya FilÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Succeed in NQESHDocument4 paginiHow To Succeed in NQESHGe Lo100% (3)

- Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning StudiesDocument93 paginiEvaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studiesmario100% (3)

- Learning Experience Plan SummarizingDocument3 paginiLearning Experience Plan Summarizingapi-341062759Încă nu există evaluări

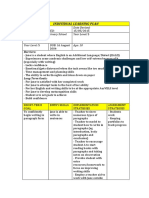

- Individual Learning PlanDocument2 paginiIndividual Learning Planjn004625100% (3)

- PDF Edited Chapter 1-5Document46 paginiPDF Edited Chapter 1-5Revtech RevalbosÎncă nu există evaluări

- LESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomDocument2 paginiLESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomCherie NedrudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short CV: Prof. Dr. Zulkardi, M.I.Komp., MSCDocument39 paginiShort CV: Prof. Dr. Zulkardi, M.I.Komp., MSCDika Dani SeptiatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddha's BrainDocument84 paginiBuddha's Brainbhanuprakash08306100% (7)

- Postoperative Psychological AssistanceDocument14 paginiPostoperative Psychological AssistanceAndréia MinskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pollio EvaluationDocument7 paginiPollio EvaluationDebbie HarbsmeierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hepp Katz Lazarfeld 4Document5 paginiHepp Katz Lazarfeld 4linhgtran010305Încă nu există evaluări

- 337TO 003 World's Largest FLNG PreludeDocument9 pagini337TO 003 World's Largest FLNG PreludeRamÎncă nu există evaluări

- ch05 Leadership AbcDocument40 paginich05 Leadership AbcFaran KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership StylesDocument16 paginiLeadership StylesAmol VazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math LessonDocument5 paginiMath Lessonapi-531960429Încă nu există evaluări

- Adgas Abu DhabiDocument7 paginiAdgas Abu Dhabikaran patelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan ForgeryDocument1 paginăLesson Plan Forgeryapi-316826697Încă nu există evaluări

- FLP10037 Japan SakuraaDocument3 paginiFLP10037 Japan SakuraatazzorroÎncă nu există evaluări