Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Globalization and Environmental Challenges - Reconceptualizing Security in The 21st Century - Hans Günter Brauch PDF

Încărcat de

Aleksandra RadosavljevićDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Globalization and Environmental Challenges - Reconceptualizing Security in The 21st Century - Hans Günter Brauch PDF

Încărcat de

Aleksandra RadosavljevićDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 27 Sonntag, 28.

Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges:

Reconceptualizing Security in the 21st Century

Hans Gnter Brauch

1.1

Introductory Remark

This book focuses on the reconceptualization of security in the 21st century that has gradually evolved since

the end of the East-West conflict (19891991) and that

has been significantly influenced by processes of globalization and global environmental change.

This global turn has resulted in the end of the

Cold War (19461989), which some historians have interpreted as a long peace (Gaddis 1987, 1997) with a

highly armed bipolar international order, the collapse

of the Soviet Union (1991) and of a competitive global

ideology, system of rule and military superpower.

These events brought about a fundamental and peaceful change in international order that made the reunification of Germany (1990) and of Europe with the

Eastern enlargement of the EU (2004, 2007) possible.

This turn has been portrayed either as a victory

of US superiority (Schweitzer 1994) or as an outcome

of a political learning (Grunberg/Risse-Kappen

1992) based on a new thinking (Perestroika) of Gorbachev that contributed to the first major peaceful

global change in modern history. This global turn

(19891991) has been the fourth major change since

the French Revolution that was instrumental for the

emergence of a new international order. Three previous turning points in modern history were the result

of revolutions (1789, 19111918) and of wars (1796

1815, 19141918, 19311949) resulting in a systemic

transformation.

This fourth peaceful turn triggered a peaceful

(Czechoslovakia) and violent disintegration of multiethnic states (USSR, Yugoslavia); it contributed to the

emergence of failing states (e.g. Somalia, Afghanistan) and to new wars (Kaldor/Vashee 1997; Kaldor

1999; Mnkler 2002, 2005). Besides the events in Europe during 1989, events in other parts of the world

had no similar impact on the new global (dis)order

during the 1990s, e.g. the death of Mao Zedong

(1976) and the economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping

in China (19781990); the end of the dictatorships

and the third wave of democratization in Latin America; and the many new wars in Africa due to weak,

failing or failed states where warlords took over control in parts of West (Liberia) and Eastern Africa (Somalia), as well as in Asia (Afghanistan).

This chapter aims at a mental mapping of the

complex interaction between this most recent global

structural change and conceptual innovation that have

occurred in academia, in international organizations

as well as in the declarations and statements of governments since 1990 up to spring 2007. It refers only

briefly to the term and concept of security (1.2, see for

details chapters 39 in this volume), to the contextual

context: events, structures, concepts and action (1.3),

to the theme of contextual change, conceptual innovation as tools for knowledge creation and action (1.4),

to the drivers and centres of conceptual innovation

(1.5), to four scientific disciplines: history, philosophy,

social sciences, and international law (1.6), to the

Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace and to the goal of the three related volumes (1.7), to the goals, structure, authors, and audience of this book (1.8) as well as to the expected

audience of this book (1.9).

1.2

Object: Term and Concept of

Security.

Security is a basic term and a key concept in the social

sciences that is used in intellectual traditions and

schools, conceptual frameworks, and approaches.

The term security is associated with many different

meanings that refer to frameworks and dimensions,

apply to individuals, issue areas, societal conventions,

and changing historical conditions and circumstances.

Thus, security as an individual or societal political value has no independent meaning and is always related

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 28 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

28

Table 1.1: Vertical Levels and Horizontal Dimensions of Security in North and South

Security dimension

Level of interaction

(referent objects)

Military

Political

Human

Environmental

Social

Social, energy, food , health, livelihood threats,

challenges and risks may pose a survival dilemma in

areas with high vulnerability

Village/Community/Society

National

Economic

Security dilemma of competing states

(National Security Concept)

International/Regional

Securing energy, food, health, livelihood etc.

(Human Security Concept) combining all levels of

analysis & interaction

Global/Planetary

to a context and a specific individual or societal value

system and its realization (see chap. 4 by Brauch).

Security is a societal value or symbol (Kaufmann

1970, 1973) that is used in relation to protection, lack

of risks, certainty, reliability, trust and confidence,

predictability in contrast with danger, risk, disorder

and fear. As a social science concept, security is ambiguous and elastic in its meaning (Art 1993: 821). Arnold Wolfers (1962: 150) pointed to two sides of the

security concept: Security, in an objective sense,

measures the absence of threats to acquired values, in

a subjective sense, the absence of fear that such values

will be attacked.

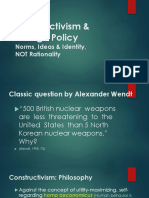

For the constructivists, security is intersubjective

referring to what actors make of it (Wendt 1992,

1999). Thus, security depends on a normative core

that can not simply be taken for granted. Political constructions of security have real world effects, because

they guide action of policymakers, thereby exerting

constitutive effects on political order (see chap. 4 by

Wver, 37 by Baylis, 51 by Hintermeier in this vol.).

The security concept has gradually widened since

the 1980s (Krell 1981; Jahn/Lemaitre/Wver 1987;

Wver/Lemaitre/Tromer 1989; Buzan/Wver/de

Wilde 1995, 1998; Wver/Buzan/de Wilde 2008; chap.

38 by Albrecht/Brauch). For Wver (1997, chap. 4 and

44) security is the result of a speech act (securitization), according to which an issue is treated as: an

existential threat to a valued referent object to allow

urgent and exceptional measures to deal with the

threat. Thus, the securitizing actor points to an

existential threat and thereby legitimizes extraordinary measures.

Security in an objective sense refers to specific security dangers, i.e. to threats, challenges, vulnerabilities and risks (Brauch 2003, 2005, 2005a) to specific

security dimensions (political, military, economic, so-

cietal, environmental) and referent objectives (international, national, human) as well as sectors (social, energy, food, water), while security in a subjective sense

refers to security concerns that are expressed by government officials, media representatives, scientists or

the people in a speech act or in written statements

(historical sources) by those who securitize dangers

as security concerns being existential for the survival

of the referent object and that require and legitimize

extraordinary measures and means to face and cope

with these concerns. Thus, security concepts have always been the product of orally articulated or written

statements by those who use them as tools to analyse,

interpret, and assess past actions or to request or legitimize present or future activities in meeting the specified security threats, challenges, vulnerabilities, and

risks.

The Copenhagen School (Buzan/Wver 1997;

Wver 1997; Buzan/Wver/de Wilde 1998; Wver/

Buzan/de Wilde 2008), distinguished among five dimensions (widening: military, political, economic, societal and environmental), and five referent objects

(whose security) or levels of interaction or analysis

(deepening: international, regional, national, domestic

groups, individual). They did not review the sectorialization of security from the perspective of national

(international, regional) and human security (Brauch

2003, 2005, 2005a; table 1.1).

Influenced by different worldviews, rival theories

and mindsets, security is a key concept of competing

schools of a) war, strategic or security studies from a

realist perspective, and b) peace and conflict research

from an idealist or pragmatic view (chap. 40 by

Albrecht/Brauch). Since 1990, interparadigm debates

emerged between traditional, critical, and constructivist approaches. Within the UN and NATO, different concepts coexist, a state-centred political and

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 29 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

29

Table 1.2: Expanded Concepts of Security (Mller 2001, 2003; Oswald 2001, 2007)

Concepts of security

Reference object

(security of whom?)

Value at risk

(security of what?)

Source(s) of threat

(security from whom/ what?)

National Security [political,

military dimension]

The state

Sovereignty,

territorial integrity

Other states, guerilla, terrorism

(substate actors)

Societal security [dimension]

Nations,

societal groups

National unity,

identity

(States) Nations, migrants,

alien cultures

Human security

Individuals,

humankind

Survival,

quality of life

State, globalization, GEC, nature,

terrorism

Environmental security

[dimension]

Ecosystem

Sustainability

Humankind

Gender security

Gender relations,

indigenous people,

minorities, children,

elders

Equality, equity,

identity, solidarity,

social representations

Patriarchy, totalitarian institutions

(governments, religions, elites,

culture), intolerance, violence

military concept, and an extended security concept

with economic, societal, and environmental dimensions. A widening and deepening of the security

concept prevailed in OECD countries, while other

countries adhered to a narrow military concept

Not only the scope of securitization (Wver

1997, 1997a) has changed, but also the referent object

from a national to a human-centred security concept, both within the UN system (UNDP 1994;

UNESCO 1997, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2003; UNU 2002;

UNU-EHS 2004), and in the academic security community.

In European security discourses, an extended security concept is used by governments and in scientific debates (Buzan/Wver/de Wilde 1998). Mller

(2001, 2003) distinguished a national and three expanded security concepts of societal, human, and

environmental security. Oswald (2001, 2007, 2008)

introduced a combined human, gender and environmental (HUGE) security concept (table 1.2).

While since the 19th century the key actor has

been the state, it has not necessarily been a major referent object of security which is often referred to as

the people or our people whose survival is at stake

(Brauch chap. 3; Albrecht/Brauch chap. 38). From

1947 to 1989 national and military security issues became a matter of means (armaments), instruments (intelligence) and strategies (deterrence). Wver (1995:

45) argued that environmental issues may pose threats

of violent conflicts and that they may also put the survival of the people at stake (e.g. by forced migration)

without a threat of war.

Whether a threat, challenge, vulnerability, and risk

(Brauch 2005a, 2006) becomes an objective security

danger or a subjective security concern also depends

on the political context. While in Europe climate

change has become a major security issue, in the US,

during the administration of George W. Bush this

problem was downgraded. Labelling climate change a

security issue implies different degrees of urgency and

means for coping with it.

The traditional understanding of security as the

absence of existential threats to the state emerging

from another state (Mller 2002: 369) has been challenged both with regard to the key subject (the state)

and carrier of security needs, and its exclusive focus

on the physical or political dimension of security

of territorial entities that are behind the suggestions

for a horizontal and vertical widening of the security

concept.

The meaning of security was also interpreted as a

reaction to globalization and to global environmental

change. In Europe, several critical approaches to security gradually evolved as the Aberystwyth (Booth,

Wyn Jones, William), Paris (Bigo, Badie) and Copenhagen (Wiberg, Wver, Mller) schools that led to

the development of a New European Security Theory

(NEST, e.g. Brger/Stritzel 2005) and a networked

manifesto (CASE 2006; chap. 38 by Albrecht/

Brauch).

1.3

Events Structures Concepts

Action

Political and scientific concepts, like security, are used

within a complex context (Koselleck 2006). These

concepts have a temporal and systematic structure,

they embody and reflect the time when they were

used and they are thus historical documents in the

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 30 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

30

persistent change in the history of short events (histoire des vnements) and long structures (Braudels

(1949, 1969, 1972) histoire de la longue dure). Concepts are influenced by manifold perceptions and

interpretations of events that only rarely change the

basic structures of international politics and of international relations (IR).

The political events of 1989, the rare coincidence

of a reform effort from the top and a yearning for

freedom and democracy from the bottom, as part of

a peaceful upheaval in East Central Europe toppled

the Communist governments in all East Central European countries within three months, and thus were instrumental for the collapse of the Soviet Union and

the dissolution of the Warsaw Treaty Organization

and the Comecon (1991).

The Cold War bipolar order of two rival highly

armed political systems with the capability to destroy

the globe with its weapons of mass destruction based

on nuclear deterrence doctrines became obsolete as

well as the traditional security legitimizations with the

arms of the other side. This structural change of the

international order influenced the security policy

agendas and provoked a global political and scientific

debate on the reconceptualization of security. This debate has been global, stimulated by many policy actors, scientists and intellectuals. The results of this

process are documented in the national security doctrines and strategies (e.g. in the US) and in defence

white papers of many countries (e.g. in Germany

1994, 2006). They have also been an object of analysis

of the scientific community that gradually emancipated itself from the US conceptual dominance

(Wver 2004; Wver/Buzan 2006). But these Northern discourses on security have been unaware and ignored the thinking of the philosophical traditions in

Asia, Africa, Latin America, and in the Arab world.

While Huntington in his clash of civilization

(1993, 1996) succeeded to securitize culture from the

vantage point of US national security interests and

strategies, the critical responses (Said; Chomsky;

Ajami) reflected the cultural and religious diversity of

the other five billion people that have been primarily

an object of security thinking and policy during and

after the Cold War.

This reconceptualization of security has impacts

on international agendas and thus on political action

on many different levels. UNDP (1994) introduced a

people-centred human security concept that was subsequently promoted by the Human Security Network

(as freedom from fear), and by the Human Security

Commission (as freedom from want), to which Kofi

Annan added as a third pillar: freedom to live in dignity and the United Nations University (UNU) as the

fourth pillar: freedom from hazard impact (Bogardi/

Brauch 2005; Brauch 2005, 2005a).

An effort of the only remaining superpower to regain control over the security discourse in its war on

terror by trying to politically adapt scientific evidence

on climate change and to constrain scientific freedom

has failed. Other efforts by a leading neo-conservative

think tank to pay scientists a fee for challenging the

fourth IPCC Report (2007) to downgrade and thus to

de-securitize these new dangers posed by anthropogenic climate change may also fail.1

The increasing perception of global environmental

change (GEC) as a threat to the survival of humankind and the domestic backlash in the US against the

narrow security concepts and policies of the Neocons has widely established a widened, deepened, and

sectorialized security concept that increasingly reflects

the existing cultural and religious diversity also in the

political debate on security as well as in scientific discourses. In this context, this volume has a dual function: a) to map this global conceptual change; and b)

to create a wide scientific and political awareness of

the new threats, challenges, vulnerabilities and risks

that often differ from the perception of the present

political elite in the only remaining superpower.

Thus, conceptualizing security concepts and defining the manifold security interests and preferences,

structures the public policy discourse and legitimates

the allocation of scarce financial resources to face

and cope with major security dangers and concerns

that threaten the survival of states, human beings or

humankind and thus require extraordinary political

action.

1.4

Contextual Change, Conceptual

Innovation as Tools for

Knowledge Creation and Action

A key analytical question to which all authors were invited to reflect is to which extent the structural

change in the global and regional international order

1

See: Ian Sample: Scientists offered cash to dispute climate study, in: The Guardian, 2 February 2007; Elisabeth Rosenthal; Andrew C. Revkin: Science Panel

Calls Global Warming Unequivocal, in: The New

York Times, 3 February 2007; Juliet Eilperin: Humans

Faulted For Global Warming International Panel Of Scientists Sounds Dire Alarm, in: Washington Post, 3 February 2007.

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 31 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

was instrumental, triggered or contributed to this conceptual innovation and diversity in the global security

discourse since 1990 or to which extent other events

or regional or national structural changes have initiated a conceptual rethinking.

From the perspective of this author, major

changes in the international order for the past 500

years have been:

The Hispanic World Order: Expulsion of the

Arabs and conquest of the Americas (14921618)

by Spain and Portugal that resulted in a global

order dominated by the Christian civilized world

that perceived the South as primitive barbarians;

The peace of Mnster and Osnabrck (1648) after

the religious Thirty Years War (16181648), and the

emergence of the Westphalian European order

based on territorial states and an emerging international law;

The Utrecht Settlement and the century of war

and peace in the order of Christian princes (1715

1814).

After the independence of the United States (1776),

the French Revolution (1789), and the wars of liberation in Latin America (18091824) and the emergence

of many new independent states (18171839) in Europe four major international orders and major global

structural and contextual changes can be distinguished:

The Peace Settlement of Vienna (1815) and the

European order of a balance of power based on a

Concert of Europe (18151914) in an era of imperialism (Africa, Asia) and the post-colonial liberation in Latin America.

The Peace of Versailles (1919) with a collapse of

the European world order, a declining imperialism

and the emergence of two new power centres in

the US and in the USSR with competing political,

social, economic, and cultural designs and a new

global world order based on the security system of

the League of Nations (19191939).

The Political Settlement of Yalta (February 1945)

and the system of the United Nations discussed at

the Conferences in Dumbarton Oaks (1944),

Chapultepec (January/ February 1945), and adopted at San Francisco (April/June 1945).

With these turning points during the European dominance of world history, the thinking on security

changed. External and internal security became major

tasks of the modern dynastic state. With the French

Revolution and its intellectual and political conse-

31

quences the thinking on Rechtssicherheit (legal predictability guaranteed by a state based on laws) gradually evolved. With the Covenant of the League of

Nation collective security became a key concept in

international law and in international relations (IR).

Since 1945, this national security concept has become a major focus of the IR discipline that gradually

spread from iAberystwyth (1919) via the US after 1945

to the rest of the world. The Cold War (19461989)

was both a political, military, and economic struggle

and an ideological, social, and cultural competition

when the modern security concept emerged as a political and a scientific concept in the social sciences

that was intellectually dominated by the American

(Katzenstein 1996) and Soviet (Adomeit 1998) strategic culture. With the end of the Cold War, the systemic conflict between both superpowers and nuclear

deterrence became obsolete and its prevailing security

concepts had to be reconsidered and adjusted to the

new political conditions, security dangers, and concerns.

This process of rethinking or reconceptualization

of security concepts and redefinition of security interests that was triggered by the global turn of 1989

1991 and slightly modified by the events of 11 September 2001 (Der Derian 2004; Kupchan 2005; Risse

2005; Mller 2005; Guzzini 2005) and the subsequent

US-led war on terror has become a truly global process.

The intellectual dominance of the two Cold War

superpowers has been replaced by an intellectual pluralism representing the manifold intellectual traditions but also the cultural and religious diversity. In

this and the two subsequent volumes authors representing the five billion people outside the North Atlantic are given a scientific voice that is often ignored

in the inward oriented national security discourses

that may contribute little to an understanding of these

newly emerging intellectual debates after the end of

the Cold War.

According to Tierney and Maliniak (2005: 5864):

American scholars are a relatively insular group who

primarily assign American authors to their students.2

In an overview of three rival theories of realism, liberalism and idealism (constructivism), Snyder (2004:

5362) listed among the founders of realism (Morgenthau, Waltz) and idealism (Wendt, Ruggie) only

Americans but of liberalism two Europeans (Smith,

Kant). Among the thinkers in all three schools of realism (Mearsheimer, Walt), liberalism (Doyle, Keohane,

Ikenberry) and idealism (Barnett and the only two

women: Sikkink, Finnemore) again only Americans

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 32 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

32

qualified. This may reflect the prevailing image of the

us and they. But in a second survey Malinak, Oakes,

Peterson and Tierney (2007: 6268) concluded that:

89 per cent of scholars believe that the war [in Iraq] will

ultimately decrease US security. 87 per cent consider the

conflict unjust, and 85 per cent are pessimistic about the

chances of achieving a stable democracy in Iraq in the

next 10 15 years. 96 per cent view the United States

as less respected today than in the past (Malinak/

Oakes/Peterson/Tierney 2007: 63).

A large majority of US IR scholars opposed unilateral

US military intervention and called for a UN endorsement. Seventy per cent describe themselves as liberals

and only 13 per cent as conservative. Their three most

pressing foreign-policy issues during the next 10 years

reflect the official policy agenda: international terrorism (50 per cent), proliferation of weapons of mass

destruction (45 per cent), the rise of China (40 per

cent). Only a minority consider global warming (29

per cent), global poverty (19 per cent) and resource

scarcity (14 percent) as the most pressing issues.r

These snapshots refer to a certain parochialism

within the IR discipline which made the perception of

the global process of reconceptualization of security,

and of new centres of conceptual innovation on security more difficult. But the thinking of the writers outside the North Atlantic and their different concerns

matter in the 21st century when the centres of economic, political, and military power may shift to other

parts of the world (see part IX in this book).

1.5

Drivers and Centres of

Conceptual Innovation

The drivers of the theoretical discourse on security

and the intellectual centres of conceptual innovation

have moved away from both Russia (after 1989) but

gradually also from the United States. During the

1980s, the conceptual thinking on alternative se-

They claimed: The subject may be international relations, but the readings are overwhelmingly American.

Almost half of the scholars surveyed report that 10 per

cent or less of the material in their introductory courses

is written by non-Americans, with a full 10 per cent of

professors responding that they do not assign any

authors from outside the United States. Only 5 per cent

of instructors give non-Americans equal billing on their

syllabuses (Tierney/Malinak 2005: 63). While one third

in the US IR field are women, among the 25 most influential scholars are only men, among them many are considered leading security experts.

curity or defensive defence in Europe was looking

for political and military alternatives to the mainstream deterrence doctrines and nuclear policies

(Weizscker 1972; Afheldt 1976; SAS 1984, 1989;

Brauch/Kennedy 1990, 1992, 1993; Mller 1991, 1992,

1995). It was a major intellectual force behind the independent peace movement that called for both disarmament and human rights in both camps (e.g.

END, 19801989).

In 2007, the discourses on security are no longer a

primarily American social science (Crawford/Jarvis

2001; Hoffmann 2001; Nossal 2001; Zrn 2003). The

critiques of peace researchers and alternative security

experts in Europe during the 1970s and 1980s, but

also new national perspectives during the 1990s, e.g.

in France (Lacoste, Bigo, Badie), in the UK (Buzan,

Booth, Smith, Rogers), Canada (Porter 2001), Germany (Albrecht, Czempiel, Senghaas, Rittberger) challenged American conceptualizations of national security. Since the 1990s in Southern Europe a reemergence of geopolitics (France, Italy, Spain) could

be observed (Brauch, chap. 22). In other parts of the

world a critical or new geopolitics school emerged

(OTuahthail, Dalby) but also a spatialization of global

challenges (ecological geopolitics or political geo-ecology). In Germany there has been a focus on progressing debordering, or deterritorialization of political processes (Wolf, Zrn) primarily in the EU while

new barriers were directed against immigration from

the South in both the US (toward Mexico) and in Europe (in the Mediterranean).

Groom and Mandaville (2001: 151) noted an increasingly influential European set of influences that

have historically, and more recently, informed the disciplinary concerns and character of IR that have

been stimulated by the writings of Foucault, Bourdieu,

Luhmann, Habermas, Beck and from peace research

by Galtung, Burton, Bouthoul, Albrecht, Czempiel,

Rittberger, Senghaas, Vyrynen. Since the 1980s, the

conceptual visions of African (Nkruma, Nyerere and

Kaunda) and Arab leaders (Nasser), as well as the

Southern concepts of self-reliance and Latin American

theories of dependencia of the 1960s and 1970s

(Furtado 1965; Marini 1973; Dos Santos 1978) had

only a minor impact on Western thinking in international relations and on security.

Since 1990 the new centres of conceptual innovation are no longer the US Department of Defense or

the US academic centres in security studies in the Ivy

League programmes. The effort by US neo-conservatives to reduce the global security agenda to weapons

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 33 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

of mass destruction and to the war on terror has also

failed, and many scholars share the scepticism.

However, most journals on security studies (e.g.

International Security) are produced in the US and

the North American market has remained the biggest

book market for the security related literature. Since

1990 new journals on IR and security problems have

evolved elsewhere, and since 1992 the triennial panEuropean Conferences on International Relations

(ECPR) in Heidelberg (1992), Paris (1995), Vienna

(1998), Canterbury (2001), The Hague (2004) and Turino (2007) have supplemented the Annual International Studies Association conferences in North

America where the intellectual debates on both security, peace, environment, and development are taking

place. In August 2005 ECPR and ISA with partners in

other parts of the world organized the first world conference on international relations in Istanbul.

In the political realm, the US as the only remaining superpower irrespective of its 48 per cent

contribution to global arms expenditures (SIPRI

2006) has lost its predominance to set and control

the international security agenda and US scholars no

longer set the theoretical, conceptual, and empirical

agenda of the scientific security discourse. In Europe

and elsewhere new centres of intellectual and conceptual innovation have emerged in the security realm:

In Europe, Aberystwyth, Paris, and Copenhagen

have been associated with three new critical

schools on security theory (Wver 2004).

The Copenhagen School combined peace research

with the Grotian tradition of the English School,

integrating inputs from Scandinavian, British, German, and French discourses (Buzan/Wver/de

Wilde 1997; Wver/Buzan/de Wilde 2008).

The human security concept was promoted by

Mahub ul Haq (Pakistan) with the UNDP report

of 1994 and then developed further with Japanese

support by the Human Security Commission

(2003) and promoted both by UNESCO and

UNU globally.

Civil society organizations in South Asia developed the concept of livelihood security.

International organizations introduced the sectoral concepts of energy (IEA, OECD), food (FAO,

WFP), water (UNEP) and health (WHO) security

(see Hexagon vol. IV).

In the US and Canada, and in Switzerland and

Norway the concept of environmental security as

33

security concerns emerged during the 1980s and

1990s.

Since 1990 the epistemic community of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

provoked a global scientific and policy debate on

climate change.

The Earth System Science Partnership (ESSP) and

its four programmes: IHDP (International

Human Dimensions Programme), IGBP (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme), WCRP

(World Climate Research Programme) and

Diversitas and its project GECHS (Global

Environmental Change and Human Security)

resulted in global scientific networks that address

new security dangers and concerns.

Trends in the reconceptulization of security that will

be mapped in the Hexagon Series are:

widening, deepening, and sectorialization of security concepts;

shift of referent object from the state to human

beings or humankind (human security);

perception of new security dangers (threats, challenges, vulnerabilities, and risks) and securitization of new security concerns due to an articulation by national and international organizations,

scientific epistemic communities, and an attentive

public with a progressing decentralization and diversity of information control through the internet;

search for new non-military strategies to face and

cope with these newly perceived security dangers

and concerns and new environmental dangers,

hazards, and disasters that pose no classical security dilemma (Herz 1950, 1959, 1962) for states but

a survival dilemma (Brauch 2004, chap. 40) for

people.

These new drivers and centres of conceptual innovation have fundamentally challenged the narrow statefocused security concept of the traditionalists and realists in the Cold War.

1.6

History, Social Sciences,

Philosophy, International Law

Events, structures, and concepts stand for three different historical approaches of:

a history of events (of states and government

elites) in diplomacy, conflicts, and wars focusing

on the activities of states during wars;

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 34 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

34

a history of structures (history of longue dure

and of conjunctural cycles) in the accounts on

social, societal, and economic history;

a history of ideas (Ideengeschichte) and concepts

(Begriffsgeschichte).

1.6.1

Contextual Change and Conceptual

History

The history of concepts was instrumental for a major

German editorial project on key historical concepts

(Brunner/Conze/Koselleck 19721997). Koselleck

(1979, 1989, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2002, 2006) addressed

the complex interlinkages between the temporal features of events, structures, and concepts in human

(societal) history but also the dualism between experience and concepts (chap. 3 by Brauch).

Conze (1984: 831862) reviewed the evolution of

the meaning of the German concepts security (Sicherheit) and protection (Schutz) that evolved based

on Roman and Medieval sources since the 17th century with the dynastic state and was closely linked to

the modern state. Since 1648 internal security was distinguished from external security which became a key

concept of foreign and military policy and of international law. During the 17th and 18th centuries internal

security was stressed by Hobbes and Pufendorf as the

main task of the sovereign for the people.

In the American constitution, safety is linked to

liberty. During the French Revolution the declaration

of citizens rights declared security as one of its four

basic human rights. For Wilhelm von Humboldt the

state became a major actor to guarantee internal and

external security while Fichte stressed the concept of

mutuality where the state as the granter of security

and the citizen interact. Influenced by Kant, Humboldt, and Fichte the concept of the Rechtsstaat (legally constituted state) and Rechtssicherheit (legal

predictability of the state) became key features of the

thinking on security in the early 19th century (Conze

1984).

The concept of social security gradually evolved

in the 19th and 20th centuries, especially during F.D.

Roosevelts New Deal as a key goal to advance the security of the citizens: the security of the home, the

security of the livelihood, and the security of the social insurance. This was addressed in the Atlantic

Charter of 1941 as securing, for all, improved labour

standards, economic advancement and social security. In 1948 social security became a key human right

in Art. 22 of the General Declaration of Human

Rights.

The national security concept in the US resulted

in the emergence of the American security system

(Czempiel 1966), or of a national security state (Yergin

1977). It was used to legitimate a major shift in the

mindset from the isolationism of the 1930s to the internationalism in the post-war years, i.e. from a fundamental criticism of military armaments to a legitimization of an unprecedented military and arms build-up

and militarization of the mindset of post-war foreign

policy elites.

The changes in the thinking on security and their

embodiment in security concepts are also a semantic

reflection of the fundamental changes as they have

been perceived in different parts of the world and

conceptually articulated in alternative or new and totally different security concepts. Competing securitization efforts of terrorism or climate change are behind

the transatlantic and global security policy debate and

the global scientific conceptual discourse.

1.6.2

Conceptual Mapping in the Social

Sciences

In the social sciences, the security concept has been

widely used in political science (chap. 37 by Baylis in

this vol.), and economics (chap. 36 by Mursheed and

43 Mesjasz) that focus on different actors: on the political realm (governments, parliaments, public, media,

citizens); on society (societal groups) and on the business community (firms, customers, economic and fiscal policies). In political science, the security concept

has been used in its threefold context: policy (field of

security policy), politics (process on security, military,

and arms issues), and polity (legal norms, laws, and

institutions on the national and international level).

The US National Security Act of 1947 (Czempiel 1966,

Brauch 1977) and its adjustments has created the legal

and institutional framework for the evolution of the

national security state, sometimes also referred to as

a military-industrial complex (Eisenhower 1972). This

evolution has been encapsulated in the US debate on

the concepts of national and since 2001 also homeland security.

1.6.3

Analysis of Concepts and their Linkages

in Philosophy

The evolution and systematic analysis of concepts has

been a major task of political philosophy and of the

history of ideas. In German several philosophical publications documented the contemporary philosophy

and its concepts in its interrelationship to their hi-

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 35 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

storical structure and the sciences.3 From a philosophical perspective after the end of the Cold War,

Makropoulos (1995: 745750) analysed the evolution

of the German concept Sicherheit from its Latin and

Greek origins and its evolution and transformation

during the medieval period, after the reformation as a

concept in theology, philosophy, politics and law,

with a special focus on Hobbes, Locke, Wolff, Rousseau, and Kant. In the 20th century he reviewed the

prevention and compensation of genuinely social and

technical insecurity as well as new social risks. While

this article briefly noted the concept of social security the key concept of national security or the more

recent concepts of human security were not mentioned.

1.6.4

Security Concepts in National Public

and International Law

Since the 18th century the security concept was widely

used in the context of constitutional or public law for

the legal system providing Rechtssicherheit for the

citizens in their engagement with the state. The concepts of international peace and security have been

repeatedly used in the Covenant and in the UN Charter where Art. 1,1 outlines its key purpose:

be limited in its impact. In addition he referred to

the defining characteristic of the concept of collective security [as] the protection of the members of the

system against a possible attack on the part of any

other member of the same system, and he noted that

the distinction drawn between the concepts of collective security and collective self-defence has been

blurred to some extent in practice, and it also has lost

relevance with respect to the United Nations because

due to the universal nature of the UN system any distinction based upon external or internal acts of aggression [have been rendered] meaningless.

1.6.5

a condition in which States consider that there is no

danger of military attack, political pressure or economic

coercion, so that they are able to pursue freely their own

development and progress. International security is thus

the result and the sum of the security of each and every

State member of the international community; accordingly, international security cannot be reached without

full international cooperation. However, security is a relative rather than an absolute term. National and international security need to be viewed as matters of degree

(UN 1986: 2).

Secretary-General Prez de Cullar noted that concepts of security are the different bases on which

States and the international community as a whole

rely for their security and he observed that the

4

3

See e.g. the historical dictionary of philosophy (Historisches Wrterbuch der Philosophie) published first in

1899 by Rudolf Eisler, and its fourth edition (1927

1930). A different approach was pursued in the new Historisches Wrterbuch der Philosophie, launched and

edited by Joachim Ritter and written by a team of more

than 1,500 scholars that has been published in twelve

volumes between 1971 and 2004. It includes four types

of contributions: a) terminological articles, b) key concepts with minor changes in history, c) combined concepts in their systematic context (e.g. in logic), and d)

historical method for more detailed articles that track

the continuity and change of concepts from Classical

Greek to contemporary philosophical treatments.

Debate on Security Concepts within the

United Nations

In a report of the Secretary-General on Concepts of

Security (UN 1986)4 that was prepared by government

experts from Algeria, Venezuela, Sweden (chair),

China, GDR, Romania, Uganda, USSR, Argentina,

Yugoslavia, Malaysia, India and Australia security was

defined as:

to maintain international peace and security, and to that

end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace 2. to develop

friendly relations among nations 3. to achieve international cooperation [and] 4. to be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations in the attainment of these

common ends.

Wolfrum (1994: 51) points to the subjective and objective elements of international security, the pursuit of

which implies a transformation of international relations so that every state is assured that peace will not

be broken, or at least that any breach of the peace will

35

The GA in Res. 37/99 of 13 December 1983 called for a

comprehensive study of concepts of security, in particular security policies which emphasize cooperative

efforts and mutual understanding between states, with a

view of developing proposals for policies aimed at preventing the arms race, building confidence in relations

between states, enhancing the possibility of reaching

agreements on arms limitation and disarmament and

promoting political and economic security (UN DOC

A/40/533). This resulted in several reports published

by the Secretary-General on the Relationship between

Disarmament and International Security (Disarmament

Study Series No. 8, 1982); on Concepts of Security

(Disarmament Study Series No. 14, 1986) and on Study

on Defensive Security Concepts and Policies (Disarmament Study Series No. 26, 1993).

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 36 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

36

group recognized the different security concepts

[that] have evolved in response to the need for national security and as a result of changing political,

military, economic and other circumstances. He

summarized the groups common understanding on

six elements of a security concept:

a) All nations have the right to security.

b) The use of military force for purposes other then

self-defence is no legitimate instrument of national

policy.

c) Security should be understood in comprehensive

terms, recognizing the growing interdependence

of political, military, economic, social, geographical and technological factors.

d) Security is the concern of all nations and in the

light of the threat of proliferating challenges to

global security all nations have the right and duty

to participate in the search for constructive solutions.

e) The worlds diversities with respect to ethnic origins, language, culture, history, customs, ideologies, political institutions, socio-economic systems and levels of development should not be

allowed to constitute obstacles to international

cooperation for peace and security.

f) Disarmament and arms limitationis an important approach to international peace and security

and it has thus become the most urgent task facing the entire international community (UN 1986:

v-vi).

Since 1990, Secretaries-General Boutros Ghali (1992,

1995) and Annan (2005) have conceptualized security

and human security that according to Annans report

In Longer Freedom is based on freedom from want,

freedom from fear and freedom to live in dignity.

For the post Cold War (19902006) years,

Michael Bothe (chap. 35) reviewed the changes in the

use of the concept of security in UNSC decisions on

activities that have been considered as threats to international peace and security or as breaches of

peace. Jrgen Dedring (chap. 46) reviewed the introduction of the human security concept in the deliberations of the Security Council as a result of the

activities of Canada on the protection of civilians in

armed conflicts while Fuentes (2002; 2008) analysed

the activities of the Human Security Network in the

promotion of a common human security agenda

within and outside of the UN system.

In the scientific disciplines reviewed in this volume, key changes could be noticed in the meaning of

the concept of security as well as in the five dimen-

sions of a wider security concept. This process of reconceptualizing security since 1990 could also be observed in statements of international organizations

(UN, OSCE, EU, OECD, NATO) and in the interfaces between security and development. Much evidence could be found for the working hypothesis that

the global turn has resulted in a reconceptualization

of security.

1.6.6

Reconceptualization of Regional

Security

New security concepts have been adopted with the

Declaration of the Organization of American States

in October 2003 in Mexico (chap. 69 by Rojas), with

the European Security Strategy of 2003 (chap. 51 by

Hintermeier) by the European Union, by the United

Nations in 2005 (chap. 47 by Einsiedel/Nitschke), as

well as by NATO (chap. 55 by Dunay; chap. 56 by Bin)

but also new collective security tasks have been taken

up by the UN Security Council.

However, this retrospective analysis is not sufficient. With the ongoing globalization process, new

transnational non-state actors (from transnational corporations, to terrorist and crime networks) have directly affected objective security dangers and subjective concerns. It is not only international terrorism

that has become a major new security danger and

thus the major object of securitization in many US national security policy statements and in numerous UN

and other resolutions by IGOs, threats to human security in other parts of the world are also posed by

the impact of global climate change via an increase in

the number and intensity of natural hazards and disasters (storms, cyclones, hurricanes but also drought)

that are caused by anthropogenic activities that are

partly responsible for the misery of those affected

most by extreme weather events (e.g. by cyclones in

Bangladesh or by drought in the Sahel zone). These

events have contributed to internal displacement and

migration and have thus reached the North as new

soft security problems (Brauch 2002; Oswald 2007).

All these developments caused by global environmental change have contributed to the emergence of

a new phase in earth history, the anthropocene

(Crutzen 2002; Crutzen/Stoermer 2000; Clark/Crutzen/Schellnhuber; Oswald/Brauch/Dalby 2008) that

poses new security dangers and concerns, and for

many people in the South and for some of the most

vulnerable and affected also a survival dilemma

(Brauch 2004, and chap. 42).

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 37 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

Thus, besides the global turn of 1990, several regional and national structural changes, the impacts of

globalization, and with global environmental change a

new set of dangers and concerns for the security and

survival of humankind are evolving. The perception of

or the securitization of these new security dangers as

threats for international, regional, national, and human security have all contributed to a reconceptualization of security.

1.7

Three Volumes on

Reconceptualizing Security

This book is the first of three volumes that address

different aspects of an intellectual mapping of the

ongoing process of reconceptualizing security. The

two related volumes address:

Facing Global Environmental Change: Environmental, Human, Energy, Food, Health and Water

Security Concepts;

Coping with Global Environmental Change, Disasters and Security Threats, Challenges, Vulnerabilities and Risks.

These three books in the Hexagon Series on Human

and Environmental Security and Peace (HESP) aim

to achieve these scientific goals: a) a global NorthSouth scientific debate on reconceptualizing security;

b) a multidisciplinary debate and learning; and c) a

dialogue between academia and policymakers in international organizations, national governments and

between academia and nongovernmental actors in

civil society and in social movements on security concepts. These three volumes focus on the conceptual

thinking on a wide notion of security in all parts of

the world that is used to legitimate the allocation of

public and private resources and to justify the use of

force both to protect and to kill people in the realization of major values.

The hexagon represents six key factors contributing to global environmental change three nature-induced or supply factors: soil, water and air (atmosphere and climate), and three human-induced or

demand factors: population change (growth and decline), urban systems (industry, habitat, pollution) and

rural systems (agriculture, food, nature protection).

Throughout the history of the earth and of the homo

sapiens these six factors have interacted. The supply

factors have created the preconditions for life while

human behaviour and economic consumption patterns have contributed to its challenges (increase in

37

extreme weather events) and fatal outcomes for human beings and society. The Hexagon series will

cover the complex interactions among these six factors and their extreme and in some cases even fatal

outcomes (hazards/disasters, internal displacements

and forced migration, crises, and conflicts), as well as

crucial social science concepts relevant for their analysis.

Issues in three research fields on environment, security, and peace, especially in the environmental security realm and from a human security perspective,

will be addressed with the goal to contribute to a

fourth phase of research on environmental security

from a normative peace research and/or human security perspective (Brauch 2003; Dalby/Brauch/Oswald

2008). This book series offers a platform for scientific

communities dealing with global environmental and

climate change, disaster reduction, environmental security, peace and conflict research, as well as for the

humanitarian aid and the policy community in governments and international organizations.

1.8

Goals, Structure, Authors and

Audience of this Book

The basic research questions this global reference

book addresses are threefold:

Did these manifold structural changes in the political order trigger a rethinking or reconceptualization of the key security concept globally, nationally, and locally?

To which extent were two other global processes

instrumental for this new thinking on security: a)

the process of economic, political, and cultural

globalization and b) the evolving perception of

the impact of global environmental change (GEC)

due to climate change, soil erosion, and desertification as well as water scarcity and deterioration?

Or were the changes in the thinking on security

the result of a scientific revolution (Kuhn 1962)

resulting in a major paradigm shift?

1.8.1

Theoretical Contexts for Security

Reconceptualizations

The first two chapters introduce into the international

debate on reconceptualizing security since 1989.

Czeslaw Mesjasz approaches the reconceptualizing of

security from the vantage point of systems theory as

attributes of social systems.

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 38 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

38

1.8.2

Security, Peace, Development and

Environment

Hans Gnter Brauch (chap. 3) introduces a conceptual quartet consisting of Security, Peace, Environment and Development that are addressed by four

specialized research programmes of peace research,

security, development, and environmental studies. After an analysis of six linkages between these key concepts, four linkage concepts will be discussed: a) the

security dilemma (for the peace-security linkage); b)

the concept of sustainable development (for the development-environment linkage); c) sustainable peace

(peace-development-environment linkage) and the

new concept of a d) survival dilemma (security-environment-development linkage). Six experts review the

debates on efforts to reconceptualize these six dyadic

linkages: 1: peace and security (chap. 4 by Ole

Wver); 2: peace and development (chap. 5 by Indra

de Soysa.); 3: peace and environment (chap. 6 by rsula Oswald Spring); 4: development and security

(chap. 7 by Peter Uvin); 5: development and environment (chap. 8 by Casey Brown); and 6: security and

environment (chap. 9 by Simon Dalby).

While since the French Revolution (1789) many

political concepts (including peace and security) were

reconceptualized, the political concepts of development and environment have gradually evolved since

the 1950s and 1970s on national and international

political agendas. The authors of chapters 4 to 9 were

invited to consider these questions:

a) Has the peace and security agenda in the UN

Charter been adapted to a global contextual

change with the disappearance of bipolarity and

the emergence of a single superpower? Has the

understanding of the classic concepts affecting

peace and security: sovereignty, non-use of force

(Art. 2,4) and non-intervention (Art. II,7 of UN

Charter) changed with the increase of humanitarian interventions and peacekeeping operations?

b) Which impact did the increase in violence in Europe since 1991, the emergence of new asymmetric, ethno-religious, internal conflicts, and the

challenge by non-state actors in a rapidly globalizing world have on the theoretical debates on the

six dyadic linkages?

c) Which impact did the change in the peace-security

dyad have on environment and development concepts? Did environment and development policies

benefit from the global turn? Was it instrumental

for the increase in failing states (Somalia, Afghanistan)?

d) Have the summits in Rio de Janeiro (UNCED,

1992) and in Johannesburg (UNSSD, 2002), and

the formulation of the Millennium Development

Goals benefited from the turn?

e) Has the attack of 11 September 2001 on the US

changed the priorities of security and development policies, nationally, regionally and globally?

Not all authors have responded to these questions,

rather they discussed questions they considered the

most relevant from their respective scientific and

research perspective. They have widened and deepened the concepts from disciplines and have introduced southern perspectives to the security discourse.

1.8.3

Philosophical, Ethical, and Religious

Contexts for Reconceptualizing Security

During the Cold War national and international security was a key policy concept for allocating financial

resources and legitimating policies on the use of

force. During this period the thinking on security of

American and Soviet scholars dominated the paradigms and conceptual debates in the West and East,

but also in the divided South. With the end of the

Cold War this conceptual dichotomy was overcome.

In the post Cold War era, prior to and after 11 September 2001, theoreticians have reconceptualized security in different directions.

Samuel P. Huntingtons (1996) simplification of a

new Islamic-Confucian threat used cultural notions

to legitimate military postures to stabilize the Western

dominance and US leadership. Huntington provoked

many critical replies by scholars from different regions, cultures and religions. Instead of reducing culture to an object for the legitimization of the military

power of one country, the authors in part III have

been asked to review the thinking on security in their

own culture or religion as it has evolved over centuries

and has and may still influence implicitly the thinking

and action of policymakers in their region.

Introducing part III, rsula Oswald Spring (Mexico, chap. 10) compares the thinking on peace in the

East, West, and South. Eight chapters were written by

authors representing different cultures and religions:

Eun-Jeung Lee (Korea, chap. 13 on: Security in Confucianism and in Korean philosophy and ethics); Mitsuo

and Tamayo Okamoto (Japan, chap. 14 on: Security

in Japanese philosophy and ethics); Naresh Dadhich

(India, chap. 15 on: Thinking on security in Hinduism

and in contemporary political philosophy and ethics

in India); Robert Eisen (USA, chap. 16 on security in

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 39 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

Jewish philosophy and ethics); Frederik Arends (Netherlands, chap. 17: security in Western philosophy and

ethics); Hassan Hanafi (Egypt, chap. 18: security in

Arab and Muslim philosophy and ethics); Jacob Emmanuel Mabe (Cameroon/Germany, chap. 19: Security in African philosophy, ethics and history of ideas);

Georgina Snchez (Mexico, chap. 20: Security in Mesoamerican philosophy, ethics and history of ideas);

Domcio Proena Jnior and Eugenio Diniz (Brazil,

chap. 21: The Brazilian view on the conceptualization

of security: philosophical, ethical and cultural contexts and issues); while Michael von Brck (Germany,

chap. 11: security in Buddhism and Hinduism), and

Kurt W. Radtke (Germany/Netherlands, chap. 12: Security in Chinese, Korean and Japanese philosophy

and ethics) compare the thinking on security in two

eastern religions and the thinking in Chinese, Korean,

and Japanese philosophy and ethics. The authors

were invited to discuss these questions:

a) Which security concepts have been used in the

respective philosophy, ethics, and religion?

b) How have these concepts evolved in different philosophical, ethical, and religious debates?

c) What are the referents of the thinking on security:

a) humankind, b) the nation state, c) society, or d)

the individual human being?

d) How are these concepts being used today and do

these religious and philosophical traditions still

influence the thinking of decision-makers on security in the early 21st century?

e) Did the global contextual change of 1990 as well

as the events of 11 September 2001 have an impact

on the religious, philosophical, and ethical debates

related to security?

The goal of this part is to sensitize the readers not to

perceive the world only through the narrow conceptual lenses prevailing primarily in the Western or

North Atlantic debates on security concepts and policies. Rather, the cultural, philosophical and religious

diversity that influence the thinking on and related

policies may sensitize policymakers.

1.8.4

Spatial Context and Referents of

Security Concepts

During the Cold War the narrow national security

concept has prevailed (table 1.2). Since 1990 two parallel debates have taken place among analysts of globalization (in OECD countries) focusing on processes

of de-territorialization and de-borderization as well as

proponents of new spatial approaches to internatio-

39

nal relations (geo-strategy, geopolitics, geo-economics). There was no significant controversy between

both schools. Both approaches may contribute to an

understanding of the co-existence of pre-modern,

modern and post-modern thinking on sovereignty and

its relationship to security. The major dividing line between both perspectives, often pursued in the tradition of realism or pragmatism, is the role of space in

international affairs (see chap. 22 by Brauch).

In the Westphalian system sovereign states may be

defined in terms of a) territory, b) people, and c) government (system of rule). Thus, the territorial category of space has been a constituent of modern international politics. No state exits without a clearly

defined territory. Spatiality is the term used to describe the dynamic and interdependent relationship

between a societys construction of space on society

(Soja 1985). This concept applies not only to the social

level, but also to the individual, for it draws attention

to the fact that this relationship takes place through

individual human actions, and also constrains and enables these actions (Giddens 1984). During the 1960s

and 1970s, spatial science was widely used in geography and it attracted practitioners interested in spatial

order and in related policies (Schmidt 1995: 798

799). However, the micro level analyses in human geography are of no relevance for international relations

where the concept of territoriality is often used as:

a strategy which uses bounded spaces in the exercise of

power and influence. Most social scientists focus

on the efficiency of territoriality as a strategy, in a large

variety of circumstances, involving the exercise of

power, influence and domination. The efficiency of

territoriality is exemplified by the large number of containers into which the earths surface is divided. By far

the best example of its benefits to those wishing to exercise power is the state, which is necessarily a territorial

body. Within its territory, the state apparatus assumes

sovereign power: all residents are required to obey the

laws of the land in order for the state to undertake its

central roles within society; boundaries are policed to

control people and things entering and leaving. Some

argue that territoriality is a necessary strategy for the

modern state, which could not operate successfully

without it (Johnston 1996: 871; Mann 1984).

This very notion of the territoriality of the state has

been challenged by international relations specialists.

Herz (1959) argued that the territorial state could easily be penetrated by intercontinental missiles armed

with nuclear weapons. In the 1970s, some globalists

announced the death of the state as the key actor of

international politics, and during the recent debate

some analysts of globalization proclaimed the end of

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 40 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

40

the nation state and a progressing deborderization

and deterritorialization have become key issues of

analysis from the two opposite and competing perspectives of globalization and geopolitique but also

from critical geopolitics. For the deborderized territories a new form of raison dtat may be needed.

The authors of part IV have been invited to

address the following questions:

a) Has the debate on security been influenced by the

two schools focusing on globalization and geopolitics as well as by pre-modern, modern, and postmodern thinking on space?

b) To which extent have there been changes in the

spatial referents of security, with regard to global

environmental change, globalization, regionalization, the nation state, as well as sub-national actors, such as societal, ethnic and religious groups,

terrorist networks, or transnational criminal

groups active in narco-trafficking?

The authors of the twelve chapters address two competing approaches of globalization vs. critical geopolitics or ecological geopolitics vs. political geo-ecology

(chap. 22 by Hans Gnter Brauch); on astructural setting for global environmental politics in a hierarchic

international system from a geopolitical view (chap.

23 by Vilho Harle and Sami Moisio); the role and contributions of the Global Environmental Change and

Human Security (GECHS) project within IHDP

(Chap. 24 by Jon Barnett, Karen OBrien and Richard

Matthew); globalization and security: the US Imperial Presidency: global impacts in Iraq and Mexico

(chap. 25 by John Saxe-Fernndez); and on: Globalization from below: The World Social Forum: A platform for reconceptualizing security? (chap. 26: by rsula Oswald Spring).

Mustafa Aydin and Sinem Acikmese (chap. 27)

discuss identity-based security threats in a globalized

world with a focus on Islam, while Bjrn Hettne

(chap. 28): in world regions as referents reviews concepts of regionalism and regionalization of security.

Bharat Karnad (chap. 29) addresses the nation state

as the key referent with a focus on concepts of national security, while Varun Sahni (chap. 30) provides

a critical analysis of the role of sub-national actors (society, ethnic, religious groups) as referents. Gunhild

Hoogensen (chap. 31) focuses on terrorist networks

and Arlene B. Tickner and Ann C. Mason (chap. 32)

on criminal narco-traffic groups as non-state actors as

referents and finally Jacek Kugler (chap. 33) offers his

ideas on reconceptualizing of security research by integrating individual level data.

1.8.5

Reconceptualization of Security in

Scientific Disciplines

The security concept is used in many scientific disciplines and programmes. In this part Jean Marc

Coicaud (chap. 34) contemplates on security as a philosophical construct, Michael Bothe (chap. 35) offers

an empirical review of the changing security concept

as reflected in resolutions of the UN Security Council,

while S. Mansoob Murshed (chap. 36) discusses the

changing use of security in economics, John Baylis

(chap. 37) reviews the changing use of the security

concept in international relations, and Ulrich Albrecht

and Hans Gnter Brauch (chap. 38) reconstruct the

changes in the security concept in security studies and

peace research. The authors were invited to discuss

these questions:

a) Did a reconceptualization of security occur in

these scientific disciplines and programmes?

b) Did the global turn of 1990 and the events of 11

September 2001 have an influence or major impact on a reconceptualization of security or have

other developments (e.g. globalization or demography) or events been more instrumental?

c) Which other factors were instrumental for a reconceptualization, e.g. of risk, risk society and modernity, that directly influence the scientific debate on

security?

1.8.6

Reconceptualizing Dimensions of

Security since 1990

Laura Shepherd and Jutta Weldes (chap. 39) introduce

into the sixth part by discussing security as the state

(of) being free from danger, and Hans Gnter Brauch

(chap. 40) contrasts the state-centred security dilemma (Herz 1959) with a people-centred survival

dilemma. Barry Buzan, Ole Wver and Jaap de Wilde

(1998) distinguished among five sectors or dimensions

of security of which they analyse in this book the military (Buzan, chap. 41), societal (Wver, chap. 44),

and environmental (de Wilde, chap. 45) security

dimensions while the political one is discussed by

Thomaz Guedes da Costa (chap. 42) and economic

one by Czesaw Mesjasz (chap. 43). They were invited

to reflect on these questions:

a) To which extent have new theoretical paradigms,

approaches, and concepts in different parts of the

world influenced the reconceptualization of security dimensions?

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 41 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Introduction: Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security

b) To which extent have different worldviews, cognitive lenses, and mindsets framed the securitization

of the five key sectors or dimensions of security?

c) To which extent has the conceptualization of the

five sectors or dimensions of security been influenced by the global turn of 1989 and by the events

of 11 September 2001?

d) Has there been a fundamental difference in the

perception of the impact of both events in

Europe, in the USA, and in other parts of the

world for the five security dimensions?

e) Has the policy relevance of different security dimensions contributed to competing security agendas, and were they instrumental for the clash

among conflicting views of security in the UN Security Council since 2002, prior to and after the

war in Iraq?

1.8.7

Institutional Security Concepts Revisited

for the 21st Century

With the end of the Cold War, the bipolar system that

relied primarily on systems of collective self-defence

(Art. 51 of UN Charter) has been overcome with the

dissolution of the Warsaw Treaty Organization in

1991. In a brief interlude from 19911994, the systems

of global and regional collective security were on the

rise, and even NATO, the only remaining system of

collective self-defence, was ready to act under a mandate of the CSCE, or since 1994 of the OSCE. However, with the failure of the UN and OSCE to cope

with the conflicts in the post Yugoslav space, since

1994 NATOs relevance grew again, and with its gradual enlargement from 16 to 27 countries, NATO has

again become the major security institution for hard

security issues while the role of the UN system and of

its regional collective security organizations expanded

also into the soft human security areas.

Since 1994, when UNDP first introduced the human security concept, this concept has been debated

by the UN Security Council (see chap. 46 by Jrgen

Dedring), in reports by the UN Secretary-General

(chap. 47 by Sebastian Einsiedel, Heiko Nitzschke and

Tarun Chhabra) and has been used by UNDP as well

as by UNESCO and other UN organizations such as

UNU (Bogardi/Brauch 2005, 2005a). The reconceptualization of security in the CSCE and OSCE since

1990 is documented by Monika Wohlfeld (chap. 49).

Four chapters review the complex reconceptualization of security by and within the European Union,

from the perspective of the chair of the EUs Military

Committee (Chap. 50 by General Rolando Mosca

41

Moschini) who presents its comprehensive security

concept, while Stefan Hintermeier (chap. 51) focuses

on the reconceptualization of the EUs foreign and security policy since 1990 and Andreas Maurer and Roderick Parkes (chap. 52) deal with the EUs justice and

home affairs policy and democracy from the Amsterdam to The Hague Programme and finally Magnus

Ekengren (chap. 53) focuses on the EUs functional security by moving from intergovernmental to community-based security concepts and policies.

Two chapters focus on the reconceptualization of

security in NATO since 1990 (Pl Dunay, chap. 55)

and on NATOs role in the Mediterranean and the

Middle East after the Istanbul Summit (Alberto Bin,

chap. 56). The security and development nexus is introduced by Peter Uvin (chap. 8), the coordination issues within the UN system is addressed by Ole Jacob

Sending (chap. 48) and the harmonization of the

three goals of peace, security, and development for

the EU by Louka T. Katseli (chap. 54). From the perspective of Germany Stephan Klingebiel and Katja

Roehder (chap. 58) carry the considerations further by

discussing the manifold new interfaces between development and security, while Ortwin Hennig and Reinhold Elges (chap. 57) review the German Action Plan

for civilian crisis prevention, conflict resolution, and

peace consolidation as a practical experience with the

reconceptualization of security and its implementation in a new diplomatic instrument. The authors of

part VII were asked to consider these questions:

a) Which concepts of security have been used by the

respective international organizations in their charter and basic policy documents? To which extent

has the understanding of security changed in the

declaratory as well as in the operational policy of

this security institution? To which extent was the

global turn of 1989 instrumental for a reconceptualization of security by the UN, its independent global and regional organizations and programmes?

b) Has there been a shrinking of the prevailing post

Cold War security concept since 11 September

2001, both in declaratory and operational terms?

To which extent has there been a widening, a

deepening or a sectorialization of security since

1990 in OSCE, EU and NATO, and to which

extent has this been reflected in NATOs role in

the Mediterranean and in the Middle East? And to

which extent did the security institutions adopt

the concepts of environmental and human security

in their policy declarations and in their operative

policy activities?

00_GEC_Hex3.book Seite 42 Sonntag, 28. Oktober 2007 1:18 13

Hans Gnter Brauch

42

1.8.8

Reconceptualizing Regional Security for

the 21st Century