Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part41

Încărcat de

MukeshChhawari0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

159 vizualizări1 paginăgg

Titlu original

The Penguin History of Early India, From the Origins to AD 1300 - Romila Thapar_Part41

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentgg

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

159 vizualizări1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part41

Încărcat de

MukeshChhawarigg

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 1

EARLY I N D I A

and commentators, and were therefore biased in favour of those in authority,

generally adhering to brahmanical theories of society irrespective of whether

or not they had widespread historical applicability. For example, caste

as described in texts such as the Dharma-shastras referred to varna distinctions, a hierarchy of ritual status creating a closed stratification of society,

apparently imposed from an early period and thereafter preserved almost

intact for many centuries. The lower castes were seen from the perspective

of the upper-caste brahman authors of the texts. Yet the actual working of

caste in Indian society permitted of variation, in accordance with local

conditions, which the authors of the Dharma-shastras were reluctant to

admit.

It is curious that there were only a few attempts to integrate the texts

studied by Indologists with the data collected by ethnographers. Both constituted substantial but diverse information on Indian society. Presumably

the bifurcation was influenced by the distinction between 'civilized' and

'primitive' peoples, the latter being said to have no literature. Those who

studied oral traditions were regarded as scholars but of another category.

Such traditions were seen as limited to bards, to lower castes and the tribal

and forest peoples, and as such not reliable when compared to the texts of

the higher castes and the elite. Had the two been seen as aspects of the same

society, the functioning of caste would have been viewed as rather different

from the theories of the Dharma-shastras.

The use of evidence from a variety of different sources that were later to

become dominant was a challenge to certain aspects of textual evidence, but

a corroboration of others, thus providing a more accurate and less one-sided

picture of the past. Evidence from contemporary inscriptions, for example,

became increasingly important. A small interest developed in genealogies

and local chronicles. James Tod gathered information from bards and local

chronicles for a history of various Rajput clans, but this did not lead to

greater interest in collecting bardic evidence or assessing the role of bards

as authors of local history. Tod tended to filter the data through his own

preconceptions of medieval European society, and was among those who

drew parallels with European feudalism, albeit of a superficial kind. He

popularized the notion that the Rajputs were the traditional aristocracy and

resisted Muslim rule, disregarding their political alliances and marriage

relations with Muslim rulers. L. P. Tessitori made collections of genealogies

and attempted to analyse them, but these never found their way into conventional histories. He too consulted local bards in Rajasthan and collected

their records.

Those interested in studying the Indian past and present through its

z

10

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner AsiaDe la EverandThe Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner AsiaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Rhetoric and Ritual in Colonial India: The Shaping of a Public Culture in Surat City, 1852-1928De la EverandRhetoric and Ritual in Colonial India: The Shaping of a Public Culture in Surat City, 1852-1928Încă nu există evaluări

- Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial IndiaDe la EverandContentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial IndiaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (5)

- Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in IndiaDe la EverandColonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in IndiaEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Romila Thapar LectureDocument4 paginiRomila Thapar LectureemasumiyatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democracy in Ancient IndiaDocument24 paginiDemocracy in Ancient IndiaVageesh VaidvanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnography After Antiquity: Foreign Lands and Peoples in Byzantine LiteratureDe la EverandEthnography After Antiquity: Foreign Lands and Peoples in Byzantine LiteratureEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Transitive Cultures: Anglophone Literature of the TranspacificDe la EverandTransitive Cultures: Anglophone Literature of the TranspacificÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Kammas Andhra Japan PDFDocument28 paginiCase Study Kammas Andhra Japan PDFbluedevil2790Încă nu există evaluări

- The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of TruthDe la EverandThe Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of TruthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender and Jewish Difference from Paul to ShakespeareDe la EverandGender and Jewish Difference from Paul to ShakespeareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Indian Notions of HistoryDocument5 paginiEarly Indian Notions of HistorytheartsylenspÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Medieval PeriodDocument7 paginiEarly Medieval PeriodDrYounis ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- JSS 066 2b Mabbett KingshipInAngkorDocument58 paginiJSS 066 2b Mabbett KingshipInAngkorUday DokrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ideology & D Interpretation of Early Indian HistoryDocument5 paginiIdeology & D Interpretation of Early Indian HistoryAnonymous aheaSNÎncă nu există evaluări

- Separated by Their Sex: Women in Public and Private in the Colonial Atlantic WorldDe la EverandSeparated by Their Sex: Women in Public and Private in the Colonial Atlantic WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Case Study of Kammas in AndhraDocument28 paginiA Case Study of Kammas in AndhrasuvromallickÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Book SummariesDocument8 paginiHistory Book SummariesrockerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social TheoryDe la EverandCulture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social TheoryEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- How Nationalist Historians Responded To Imperialist HistoriansDocument4 paginiHow Nationalist Historians Responded To Imperialist HistoriansShruti JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Reviews: (Kulturstufen)Document3 paginiBook Reviews: (Kulturstufen)YAEL JUAREZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bateille, Srinivas, Damle and Shahani - Caste - A Trend Report and BibliographyDocument17 paginiBateille, Srinivas, Damle and Shahani - Caste - A Trend Report and BibliographySiddharth JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Sexuality Floated Free of HistoriesDocument19 paginiWhen Sexuality Floated Free of HistoriesparamideÎncă nu există evaluări

- Luxury and the Ruling Elite in Socialist Hungary: Villas, Hunts, and Soccer GamesDe la EverandLuxury and the Ruling Elite in Socialist Hungary: Villas, Hunts, and Soccer GamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approaches To The Study of Early Indian HistoryDocument3 paginiApproaches To The Study of Early Indian Historykanak singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in IndiaDe la EverandThe Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why History Is Important To PoliticsDocument12 paginiWhy History Is Important To Politicspg382Încă nu există evaluări

- Guha-The Small Voice of HistoryDocument8 paginiGuha-The Small Voice of HistoryCuerpos Insanos100% (1)

- Kin Clan Raja and Rule: State-Hinterland Relations in Preindustrial IndiaDe la EverandKin Clan Raja and Rule: State-Hinterland Relations in Preindustrial IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Social Space of Language VernacularDocument4 paginiThe Social Space of Language VernacularMadhurima GuhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inventing the New Negro: Narrative, Culture, and EthnographyDe la EverandInventing the New Negro: Narrative, Culture, and EthnographyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Casteinpractice ShailMayaramDocument27 paginiCasteinpractice ShailMayaramSafwan AmirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pollock The Death of Sanskrit 2001Document35 paginiPollock The Death of Sanskrit 2001Phil CipollaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shades of Colour: The Tribal In Indian FictionDe la EverandShades of Colour: The Tribal In Indian FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Concept of Tribe André BeteilleDocument4 paginiOn The Concept of Tribe André Beteillehimanshu mahatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sexuality of History: Modernity and the Sapphic, 1565–1830De la EverandThe Sexuality of History: Modernity and the Sapphic, 1565–1830Încă nu există evaluări

- Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference - New EditionDe la EverandProvincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference - New EditionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (30)

- Order and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileDe la EverandOrder and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descent Into Discourse: The Reification of Language and the Writing of Social HistoryDe la EverandDescent Into Discourse: The Reification of Language and the Writing of Social HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Culture of Sex in Ancient ChinaDocument241 paginiThe Culture of Sex in Ancient Chinadurapacz100% (2)

- Debate On Indian FeudalismDocument19 paginiDebate On Indian FeudalismGourav Shaw50% (2)

- The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and IdentityDe la EverandThe Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and IdentityEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (151)

- HIST2450 Take HomeDocument6 paginiHIST2450 Take Homezcolli01Încă nu există evaluări

- Marxism and Indian Academics (Shankar Sharan)Document16 paginiMarxism and Indian Academics (Shankar Sharan)RajeshkumarGambhavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Death of Sanskrit Sheldon PollockDocument35 paginiDeath of Sanskrit Sheldon PollockMatsyendranatha100% (1)

- Colonial Constructions of The 'Tribe'Document32 paginiColonial Constructions of The 'Tribe'Michelle Sanya TirkeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Religion of Numa and other essays on the Religion of Ancient RomeDe la EverandThe Religion of Numa and other essays on the Religion of Ancient RomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sex in Ancient China PDFDocument241 paginiSex in Ancient China PDFsynupps100% (3)

- The Impact of Cultural and Historical Context On Literary InterpretationDocument2 paginiThe Impact of Cultural and Historical Context On Literary Interpretationdidy43Încă nu există evaluări

- History: (For Under Graduate Student)Document15 paginiHistory: (For Under Graduate Student)zeba abbasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lectures on Philosophy: The Philosophy of History, The History of Philosophy, The Proofs of the Existence of GodDe la EverandLectures on Philosophy: The Philosophy of History, The History of Philosophy, The Proofs of the Existence of GodÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Scientific Theory of Culture and Other EssaysDe la EverandA Scientific Theory of Culture and Other EssaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oschema 2006Document27 paginiOschema 2006ColoVoltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hinduism World: The LvfodernDocument11 paginiHinduism World: The LvfodernDavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imperial Encounters: Religion and Modernity in India and BritainDe la EverandImperial Encounters: Religion and Modernity in India and BritainEvaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (3)

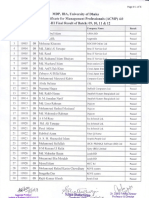

- MD HR 7Document1 paginăMD HR 7MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- As Proff SyllabusDocument10 paginiAs Proff SyllabusMukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 1Document15 paginiCH 1mca_javaÎncă nu există evaluări

- © Ncert Not To Be RepublishedDocument10 pagini© Ncert Not To Be RepublishedMukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 1Document15 paginiCH 1mca_javaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HHSC 1 PsDocument12 paginiHHSC 1 PsMukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part43Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part43MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- UN System Chart 2015 Rev.4 ENG 11x17colourDocument1 paginăUN System Chart 2015 Rev.4 ENG 11x17colourdanialme089Încă nu există evaluări

- MD HR 11Document1 paginăMD HR 11MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part45Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part45MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part47Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part47MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part31Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part31MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- JDocument1 paginăJMukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part44Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part44MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part40Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part40MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part34Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part34MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part33Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part33MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part38Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part38MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part37Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part37MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part36Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part36MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part42Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part42MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part32Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part32MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part39Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part39MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part36Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part36MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part29Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part29MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part28Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part28MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part27Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part27MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part28Document1 paginăThe Penguin History of Early India, From The Origins To AD 1300 - Romila Thapar - Part28MukeshChhawariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baruch Spinoza I. BiographyDocument7 paginiBaruch Spinoza I. BiographyMark BinghayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harvest Thanksgiving Eucharist ST Marys 2020Document12 paginiHarvest Thanksgiving Eucharist ST Marys 2020Niall James SloaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daftar Anggota Komunitas MGMP SMK Teknik Otomotif Teknik Kendaraan Ringan TKRDocument18 paginiDaftar Anggota Komunitas MGMP SMK Teknik Otomotif Teknik Kendaraan Ringan TKRWahyono YonoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conscience Subjtv NormDocument13 paginiConscience Subjtv NormRiza Mae MerryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samson and DelilahDocument5 paginiSamson and DelilahZarah RoveroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gilas Summary SampleDocument8 paginiGilas Summary SampleRey AllanÎncă nu există evaluări

- It's The Most Wonderful Time of The YearDocument2 paginiIt's The Most Wonderful Time of The YearHarryÎncă nu există evaluări

- ATTA Tribe AloDocument8 paginiATTA Tribe AloMarlyn MandaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor Who Christmas 2013 - The Night Before ChristmasDocument11 paginiDoctor Who Christmas 2013 - The Night Before Christmasapi-243383892Încă nu există evaluări

- Muslim Girl Names - Girl Names From The Quran - 2175 Muslim Names - Page 3Document5 paginiMuslim Girl Names - Girl Names From The Quran - 2175 Muslim Names - Page 3Nadir IqbalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Download Test Bank For Financial Algebra Advanced Algebra With Financial Applications 2nd Edition PDF FreeDocument32 paginiFull Download Test Bank For Financial Algebra Advanced Algebra With Financial Applications 2nd Edition PDF FreeKevin Jackson100% (6)

- Contributions To The World by GreeceDocument4 paginiContributions To The World by GreeceEmma WatsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Medicine DaysDocument407 paginiHistory of Medicine Dayssujithsnair100% (10)

- Buddhist Tenet System by Rigpa WikiDocument3 paginiBuddhist Tenet System by Rigpa WikiAadarsh LamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 19-08-11 Luke 19 - 1-10 Jesus Our Seeker and SaviorDocument7 pagini19-08-11 Luke 19 - 1-10 Jesus Our Seeker and SaviorFrederick Paulo TomacderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddhist Councils Everything You Need To KnowDocument4 paginiBuddhist Councils Everything You Need To KnowNITHIN SINDHEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eva Luna Isabel Allende ResumenDocument5 paginiEva Luna Isabel Allende Resumenphewzeajd100% (2)

- Donald F. Lach - The Sinophilism of Christian Wolff (1679-1754)Document15 paginiDonald F. Lach - The Sinophilism of Christian Wolff (1679-1754)Cesar Jeanpierre Castillo GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jisscor Union v. TorresDocument2 paginiJisscor Union v. TorresAngelo TiglaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poets of The Tang Dynasty: Li PoDocument52 paginiPoets of The Tang Dynasty: Li PothinorangelineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towns, Traders and CraftspersonsDocument16 paginiTowns, Traders and CraftspersonsLakshaya SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gangges MahamudraDocument7 paginiGangges MahamudraNyurma Palmo100% (1)

- Reference Material For Study Training Course With Mr. Morinaka - 15 & 16 Oct 2016Document68 paginiReference Material For Study Training Course With Mr. Morinaka - 15 & 16 Oct 2016Sinjini Chanda100% (1)

- Four Prominent Imams of Ahle Sunnah Wal Jamaat and Their DifferencesDocument1 paginăFour Prominent Imams of Ahle Sunnah Wal Jamaat and Their DifferencesMohammed Irfan ShaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Sculpture PDFDocument2 paginiIndian Sculpture PDFMarathi CalligraphyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AyurvedaDocument26 paginiAyurvedabhattshÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultDocument6 paginiACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultasmreazÎncă nu există evaluări

- James Boswell "On War"Document6 paginiJames Boswell "On War"Melissa LÎncă nu există evaluări

- Al GhazaliDocument4 paginiAl GhazaliIsmail BarakzaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- LM and CatastropheDocument19 paginiLM and CatastropheCharlie KeelingÎncă nu există evaluări