Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

OBESITY AND PREGNANCY OUTCOMES

Încărcat de

Achmad Deza FaristaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

OBESITY AND PREGNANCY OUTCOMES

Încărcat de

Achmad Deza FaristaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 2011; Early Online, 15

2011 Informa UK, Ltd.

ISSN 1476-7058 print/ISSN 1476-4954 online

DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2011.575905

Abnormal maternal body mass index and obstetric and neonatal outcome

N MANZANARES GALA

N, A

NGEL SANTALLA HERNA

NDEZ,

SEBASTIA

NS, &

IRENE VICO ZUNIGA, M. SETEFILLA LOPEZ CRIADO, ALICIA PINEDA LLORE

LUIS GALLO VALLEJO

JOSE

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 217.216.58.115 on 05/26/11

For personal use only.

Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital, Fuerzas Armadas Av 2, 18014, Granada, Spain

Abstract

Objective. The objective of this study is to examine the effects of abnormal maternal body mass index (BMI), either underweight

or severe or morbid obesity (BMI 435), on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes.

Methods. A three-year period (2.0072.009) observational retrospective study was carried out in Granada (Spain). Women were

categorized by first ten weeks of pregnancy BMI, according to World Health Organization (WHO) into three groups: underweight

(518.5), normal (2024.9), and severe or morbid obese (435). Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes were evaluated using normal

group as reference after suitable adjustments for confounding factors.

Results. 3.016 patients out of 12.781 single births were included. Maternal BMI classified 168 women (5.5 %) as

underweight, 2.597 (86.1%) as normal, and 251 (8.3%) as severe or morbidly obese. As compared to normal women,

underweight women were younger, and class II or III obese showed higher parity and higher incidence of hypertension

disorders and Diabetes Mellitus. After controlling for these confounders, underweight women showed increased adjusted risk

of oligohydramnios and low birth weight babies, and severe or morbidly obese women had an increased adjusted risk of

Streptococcus Group B colonization, induction of labour, elective and emergency cesarean section, fetal macrosomia, fetal

acidosis at birth, and perinatal mortality.

Conclusions. Severe or morbid obesity were associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcome and mortality and

should be managed as high-risk pregnancies.

Keywords: Obesity, underweight, pregnancy, perinatal outcome, pregnancy complications, perinatal mortality

Introduction

Obesity, defined as abnormal fat accumulation that leads to

excessive body weight, is commonly classified based on the

body mass index (BMI) values, defined as the weight in

kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/

m2) [1]. World Health Organization defines overweight as a

BMI equal to or more than 25 and obesity as a BMI 30.

Obesity can be further characterized by BMI as class I or

moderate (BMI 3034.9), class II or severe (BMI 3539.9),

and class III or morbid obesity (BMI equal to or more than

40). Underweight is also defined as a BMI below 18.5 [2].

Obesitys increasing prevalence has reached epidemic

proportions in all developed countries and has become an

important health concern. In Spain, nearly 40% of adult

population is overweight, and more than 15% is obese [3].

During pregnancy, obesity has been related to several

obstetric and fetal complications, such as hypertensive

disorders, gestational diabetes mellitus, preterm delivery, fetal

macrosomia, and unexplained stillbirths [48]. On the other

hand, few data are available about the relationship between

underweight and perinatal complications.

The aim of this study was to examine pregnancy outcomes

in women with abnormal early pregnancy weight by studying

a large number of singleton pregnancies from an unselected

population in Granada (Spain), in order to examine whether

low or extremely high maternal BMI is associated with poorer

pregnancy outcomes compared with women with normal BMI

and to quantify such risk after adjustment for conceivable

confounders, in order to provide accurate data for counseling

and prenatal surveillance.

Methods

A casecontrol study was conducted involving all women with

singleton pregnancies attended at Virgen de las Nieves

University Hospital (Granada, Spain) between 2007 and

2009, for whom BMI was available. Maternal BMI was

determined at the first prenatal visit, provided that this

happened before 10th week of pregnancy.

Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes were compared according to the maternal BMI in the three groups: underweight

(BMI 518.5), normal weight (BMI between 18.5 and 25),

and class II or III obesity (BMI 435). The maternal weight

and height information were recorded by the general

practitioner at the time of confirming pregnancy by urine test.

Primary outcome was the overall perinatal mortality from

20 weeks of gestation to 28 days of postnatal life. Secondary

outcomes included gestational age at delivery (days), preterm

(Received 30 December 2010; revised 20 March 2011; accepted 23 March 2011)

Correspondence: Dr. Sebastian Manzanares, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital, Fuerzas Armadas Av 2,

18014, Granada, Spain. Tel: +34-958020334. Fax: +34-958020089. E-mail: smanzanares@sego.es

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 217.216.58.115 on 05/26/11

For personal use only.

S. Manzanares Galan et al.

delivery rate (below 37 and 33 weeks), and postdate rate

(4290 days); other pregnancy conditions such as the

occurrence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (birth

weight 510th percentile) during pregnancy, low birth weight

(52500 g), macrosomia (4400 g) at birth, oligohydramnios

(amniotic fluid (AF) index below 5th percentile), and Group

B Streptococcus (GBS) rectovaginal colonization status; labor

and delivery data such as onset of labor (labor induction

procedures and elective cesarean section (CS)), instrumental

vaginal delivery, emergency CS for dystocia and for nonreassuring fetal status (NRFS), episiotomy, and meconiumstained AF rates; and neonatal outcomes such as fetal acidosis

(umbilical artery (UA) pH 57.10, low Apgar score (55 at

1or 57 at 5) and admissions to neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU). All data were collected from personal clinical

records.

Maternal age, parity, number of prenatal visits, preexisting

or gestational hypertension, and diabetes were thought to be

potential confounding factors, so they were analyzed earlier,

and those variables that showed differences between groups

were included as covariates in the adjusted analyses.

Data were processed with SPSS 15.0 statistical processor

software, and a descriptive analysis of the main variables was

made calculating the central tendency and dispersion measurements for quantitative variables and the absolute and

relative frequencies for qualitative variables. Groups were

compared using the analysis of variance test for quantitative

variables, and Chi-square test for qualitative variables. The

risk of perinatal complications was presented as adjusted

Odds Ratios (OR) relative to the normal BMI obtained for

other BMI categories (underweight and severe or morbidly

obese), together with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) to

summarize the effects of class II or III obesity and underweight. Level of significance of 0.05 was considered in all

analyses.

Results

Maternal BMI data were available and recorded before the

10th week of gestation for 3016 patients of 12,781 births

(23.5%). Of these, 168 (5.5%) were underweight, 2597

(86.1%) had normal BMI, and 251 (8.3%) were class II or III

obese. Maternal age and parity were significantly lower in

underweight group, and parity was significantly higher in class

II and III obese group. On the other hand, class II or III obese

mothers were much more likely to present or develop

hypertension or diabetes mellitus. All women recruited in

this study attended similar number of prenatal visits (Table I).

So adjustments were made for maternal age, parity, hypertension, and diabetes.

Table II presents the risk of obstetric conditions in the

abnormal BMI categories in comparison with the normal

group. Underweight women had a higher risk of oligohydramnios (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.144.63), and severe or

morbidly obese women had a higher risk of rectovaginal

GBS colonization (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.152.13). The

incidence of preterm delivery or postdates was not significantly different in the three BMI categories.

Labor and delivery outcomes are listed in Table III. The

adjusted risks of induction of labor and elective CS as the

way of onset of labor were higher in severe or morbidly obese

women. Emergency CS were more common in the severe or

morbidly obese group, so for dystocia and for NRFS. On the

other hand, underweight women seemed to be protective

against emergency CS. There was no association between

BMI and instrumental vaginal delivery. Severe or morbid

obesity seemed to be protective against episiotomy in

delivery, but adjusted risk showed no differences. In

the same way, the incidence of meconium-stained AF was

higher in obese, but adjusted analysis did not show

significant risk.

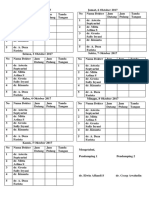

Table I. Demographic and pregnancy characteristics.

Underweight (n 168)

Normal weight (n 2597)

Class II or III obesity (n 251)

p value

17.6 + 0.7

26.9 + 6.8

78 (46.4)

9.14 + 2.6

5 (3%)

7 (4.2%)

21.9 + 1.7

30.4 + 5.7

1132 (43.5)

9.61 + 3.8

47 (1.8%)

169 (6.5%)

40 + 4.6

29.7 + 2.84

90 (35.8)

9.84 + 2.57

40 (15.9%)

63 (25.1%)

50.001

50.001

50.005

ns

50.001

50.001

Maternal early pregnancy BMI*

Maternal age (years)*

Parity (% nulliparous){

Prenatal visits*

Hypertension{

Diabetes mellitus

ns, no signification.

*Expressed in mean + standard deviation.

{

Expressed in number (%).

Table II. Obstetric outcomes I: pregnancy.

Normal weight (n 2597)

n (%)

Preterm birth 537 weeks

Preterm birth 533 weeks

Postdate 4290 days

IUGR

Oligohydramnios

GBS carrier

256

64

174

171

114

332

(9.9)

(2.5)

(6.7)

(6.6)

(4.4)

(14.3)

Underweight (n 168)

n (%)

21

5

12

16

14

19

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

(12.5)

(3)

(7.1)

(9.5)

(8.3){

(12.1)

*Adjustments were made for maternal age, parity, hypertension, and diabetes.

{

p 5 0.05.

1.35

0.99

0.81

1.65

2.3

0.72

(0.762.39)

(0.303.28)

(0.351.91)

(0.853.19)

(1.144.63)

(0.381.39)

Class II or III obesity (n 251)

n (%)

25

10

10

11

9

48

(10)

(4)

(4)

(4.4)

(3.6)

(22.2){

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

1.08

1.49

0.72

0.79

0.56

1.57

(0.701.67)

(0.623.55)

(0.341.55)

(0.361.69)

(0.191.62)

(1.152.13)

Obesity, underweight, and perinatal outcome

Table III. Obstetric outcomes II: labor and delivery.

Normal weight (n 2597)

Underweight (n 168)

n (%)

Induced labor

Instrumental vaginal delivery

Episiotomy{

Meconium-stained AF

Elective CS

Emergency CS

Emergency CS for dystocia

Emergency CS for NRFS

818

526

1262

393

176

301

175

127

n (%)

(31.5)

(20.3)

(59.5)

(15.1)

(6.8)

(11.6)

(6.7)

(4.9)

52

41

91

19

9

9

6

3

Class II or III obesity (n 251)

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

(31)

(24.4)

(60.7)

(10.7)

(5.4)

(5.4){

(3.6)

(1.8)

1.06

1.17

1.05

0.53

0.87

0.32

0.40

0.21

(0.691.62)

(0.701.96)

(0.671.66)

(0.271.04)

(0.372.06)

(0.110.88)

(0.121.29)

(0.031.58)

n (%)

104

38

73

50

35

59

34

25

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

{

(41.4)

(15.1)

(46.5)

(19.9)

(13.9){

(23.5){

(13.5){

(10){

1.68

0.83

0.70

1.40

2.01

2.19

1.87

2.32

(1.222.33)

(0.511.33)

(0.321.54)

(0.942.09)

(1.253.25)

(1.443.34)

(1.123.14)

(1.244.34)

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 217.216.58.115 on 05/26/11

For personal use only.

*Adjustments were made for maternal age, parity, hypertension, and diabetes.

{

p 5 0.05.

{

Percentage of vaginal deliveries.

Table IV. Neonatal outcome.

Normal weight (n 2597)

n (%)

BW 4 4000 g

BW 5 2500 g

UA pH 5 7.10

Low Apgar score

Admission in NICU

Perinatal mortality

81

300

84

20

51

69

(3.1)

(11.6)

(3.8)

(0.8)

(2)

(2.7)

Underweight (n 168)

n (%)

4

28

5

1

1

5

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

(2.4)

(16.7){

(3.3)

(0.6)

(0.6)

(3)

1.09

1.73

0.30

1.08

0.39

1.37

(0.383.11)

(1.042.89)

(0.042.22)

(0.138.55)

(0.052.95)

(0.483.91)

Class II or III obesity (n 251)

n (%)

24

25

15

5

8

11

Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

{

(9.6)

(10)

(6.9){

(2)

(3.2)

(4.4){

2.32

0.83

2.15

2.01

0.77

2.52

(1.294.17)

(0.481.42)

(1.054.38)

(0.508.05)

(0.242.44)

(1.215.22)

*Adjustments were made for maternal age, parity, hypertension, and diabetes.

{

p 5 0.05.

Neonatal outcomes are listed in Table IV. Newborns from

severe or morbidly obese women were fatter, and the adjusted

risk of macrosomia was 2.3 times higher in this group

compared to normal BMI group. On the contrary, underweight seemed to be a risk factor for low birth weight. Severe

or morbidly obese women showed two times risk of having

fetal acidosis, although no differences were observed in Apgar

test scores or NICU admissions. The risk of perinatal death

was significantly higher in class II and class III obese.

Discussion

BMI is highly correlated with body composition and has

become a standard measure for clinicians to classify patients

as underweight, overweight, or obese [1]. The complications

of maternal obesity in pregnancy, in general, are related to

pregravid weight rather than gestational weight gain or weight

at delivery [9]. In our study, we have taken into account height

and weight recorded in early pregnancy, before any real

impact of gestational weight gain or loss at all, as we consider

like other authors that is representative of pre-pregnancy

maternal weight [10].

The BMI classification used for this study has previously

been used to examine the relationship between body fat and

pregnancy outcome [8], although we found in literature, a

variety of groups and definitions, and this made comparison of

studies somehow difficult. Particular to this study is the

inclusion of class II and class III obese mothers next to

underweight category in the data analysis.

The prevalence of obesity has increased among women in

many countries in recent decades. In this study, 8.3% of

women were severe or morbidly obese. Horno et al. [11] in a

Spanish population found the same percentage for extreme

obesity (BMI criteria not communicated), and Doherty et

al. [12] found a 5% of obese pregnant women (BMI 430).

Most studies in European countries find that significant

maternal obesity is present in up to 610% of all pregnancies

[9,13].

On the other hand, in our population, 5.5% of women were

underweight. Sebire et al. [14] described a 17.7% of underweight (BMI 520), and Doherty et al. [12] a 11% (BMI

518.5) in an Australian population. These different results

may be influenced by differences in social and dietary habits,

besides a different cut-off in BMI values.

Although it has been reported that increasing age is an

added risk factor for obesity [13], the mean age of severe or

morbidly obese women did not significantly differ from the

normal BMI group in this study. We found that maternal age

was significantly lower in underweight mothers. As in other

studies [12], compared to women with a normal prepregnancy BMI, fewer of the obese women were nulliparous.

Along with hyperinsulinemia, maternal obesity is associated with hyperlipidemia, which reduces prostacyclin secretion and enhances peroxidase production, resulting in

vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation, which increases

the risk of hypertension. Thus, previous studies have shown

that obesity is strongly related to a higher incidence of

hypertension in pregnancy [5,8,15]. In this study, severe

or morbidly obese women (435 BMI) showed an eight

times higher incidence of any hypertension disorder than

normal BMI women. If we take into account that we included

gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, the risk found here

may be similar to the findings of Bhattacharya et al. [10], who

found three times higher risk of preeclampsia in obese (BMI

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 217.216.58.115 on 05/26/11

For personal use only.

S. Manzanares Galan et al.

3039.9) and a seven times higher risk in morbidly obese

(BMI 4 40) primigravid women compared to normal BMI

women.

These authors [10] also found a significantly lower risk of

preeclampsia in underweight women (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.5

0.7), as well as Sebire et al. [14] (OR 0.76, CI 0.620.92).

However, we did not find any difference in our data.

Overweight is a risk factor for impairment of carbohydrate

tolerance. As in other studies [8,1618], a higher incidence of

diabetes mellitus has also been found in this study in severe or

morbidly obese mothers. Underweight mothers showed

similar incidence to that in normal women. These data are

contrary to Sebire et als findings [14], who found that the

odds of gestational diabetes mellitus was significantly lower in

the underweight women (0.58, CI 0.480.70).

After controlling for these confounders (maternal age,

parity, hypertension, and diabetes), we found in this study, an

increased risk of GBS colonization in severe and morbidly

obese women. Colonization of the human rectovaginal tract

with GBS is a risk factor associated with chorioamnionitis and

transmission of the infection to the infant. This risk was also

pointed out by Stapleton et al. [19] (OR 1.201.45 for BMI

430). Furthermore, Hakansson et al. [20] found that

maternal obesity is a risk factor associated with increased risk

of neonatal early onset GBS disease.

The adjusted risk of preterm delivery, either 537 or 533

weeks, was similar in all groups in this study, in contrast to the

results of the meta-analysis of Torloni et al. [6]. Our data

confirm those from Cnattingius et al. [15] and Bhattacharya

et al. [10], who also failed to show any differences in the risk of

preterm delivery (delivery before 37 completed weeks) in the

different BMI categories. A decreased risk of preterm birth

without preterm rupture of membranes in obese women has

also been published [21].

On the other hand, Sebire et al. [14] found that delivery

before 32 weeks was significantly less likely among underweight women; meanwhile, Salihu et al. [22] found that lean

mothers were more likely to experience a preterm delivery.

This study found no significant effect of maternal underweight

on preterm delivery.

We found that severe or morbid obesity does not modify

the risk of IUGR. A previous study by Cnattingius et al. [15]

showed that higher maternal weight before pregnancy protects

against the delivery of a small-for-gestational age (SGA)

infant, and Kliegman et al. [18] concluded that the incidence

of neonates small for date is one half that observed in lean

mothers. However, other studies suggest that IUGR is not

influenced by BMI [17,23], and even Perlow et al. [24]

described and increased risk (OR 9.3).

In the underweight group, the incidence of IUGR was

higher, but the adjusted risk was also similar. The authors

think this may be due to type II statistical error (small sample

size). Thus, Rodriguez et al [25] and Doherty et al. [12] found

a higher incidence in underweight pregnant women, though

this has not been confirmed by other investigators [26].

Otherwise, in this study, underweight mothers showed an

increased risk of oligohydramnios not associated with any

other fetal condition. This finding has not been described in

any paper in the literature, yet.

Although an increased risk of postdates has not been

demonstrated in this article and previously [16], these women

do appear to require induction of labor more frequently

(adjusted OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.222.33) [10,27]. This has been

explained previously in other medical conditions such as

diabetes or preeclampsia, but an adjusted risk after controlling

for diabetes and hypertension, as in this article, led us to

consider inductions for other indications.

Our results agree with earlier reports that have shown an

association between increasing BMI and cesarean delivery

[10,27] and confirm that this increase in adjusted risk is twofold, either for elective or emergency CS, and for any

indications, though the risk of CS for NRFS is higher. The

incidence of meconium-stained AF was significantly higher in

class II and class III obese group, but after controlling for

diabetes and hypertension, the adjusted risk was not higher.

As Sevier et al. [28], we did not find any increased risk of

instrumental delivery, whereas Weiss et al. [17] did find an

increased risk of this mode of delivery (OR 1.7).

Underweight women had a lower risk of emergency CS,

with the same incidence of labor induction and operative

vaginal delivery. Sebire et al. [14] also reported a decrease in

risk of CS, although they also found a lower incidence of

inductions and operative vaginal delivery.

In addition to the increased fetal morbidity associated with

obstetric complications in the obese woman, fetal overgrowth

is also a major concern. While the risk of low birth weight

(birth weight less than 2500 g) was higher in underweight

women, as in other studies [25,26,29], the adjusted risk of

macrosomia (birth weight more than 400 g) was 2.3 times

higher in the severe or morbidly obese group. These data

confirm and outstrip other groups findings [10,23,24] that

have concluded that obese women have an OR ranging

between 1.5 and 2.2 of delivering large for date infants, even

after controlling for maternal diabetes. Two theories have

been proposed for this linear relationship between maternal

BMI and fetal birth weight: A surplus amount of fuels

provided to the fetus of the obese mother or genetic and

constitutional factors in mothers inherited by their infants

[18].

Increased risks of factors leading to perinatal morbidity,

such as admission to special care unit, have been reported in

only a few studies [24,30]. Risk factors and fetal conditions

evaluated in this study did not lead to an increase in

admissions to NICU, either in neonates from underweight

mothers or in neonates from severe or morbidly obese

mothers. We did not find any differences in Apgar score, as

found by Perlow et al. [24] (OR 3.0), but we did find an

increased risk of low UA pH at birth.

Several investigations [7,15,16,27] have suggested an

increased risk of intrauterine fetal demise of the fetus in obese

pregnant women and that this increase seems to be influenced

by the degree of obesity. The pathophysiology proposed for

this fact is a conjunction of maternal hyperinsulinemia and

placental insufficiency and a decreased ability to perceive a

reduction in fetal movement. In this study, we also confirmed

a higher adjusted risk of perinatal mortality in class II and class

III obese mothers.

In summary, this study found a higher incidence of

hypertension and diabetes in class II and class III obese

mothers and, after controlling for these conditions, maternal

age, and parity, points out an association between severe or

morbid maternal obesity and a number of threatening

complications for pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal status,

such as GBS colonization, induction of labor, CS, fetal

macrosomia, acidosis at birth, and over all, an increased

perinatal mortality. At the far end, underweight showed also

an increased risk of oligohydramnios and SGA fetuses and a

decreased risk of emergency CS.

J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 217.216.58.115 on 05/26/11

For personal use only.

Obesity, underweight, and perinatal outcome

A limitation of our study was that maternal early pregnancy

weight data were only available for 24% of all deliveries. This

is a general objection to many studies [12,15], and the lack of

information is attributed to the prenatal record not always

complete for weight and height data, as we excluded pregnant

women who attended their first visit in pregnancy after the

10th week. While this seemed to be universal throughout the

BMI categories, we cannot exclude the possibility of a

selection bias from being present in our results.

In conclusion, our results suggest that in a universal healthcare system, severe or morbidly obese mothers carry an

increased risk of adverse perinatal outcome and mortality.

These findings provide further justification for the need of

pre-pregnancy advice and counseling to young women and

could be a convincing argument for weight amendment and,

as pregnancy is a life event in which women are inclined to

behavioral changes, the development of effective strategies to

reverse the trends toward increasing.

This study clearly demonstrates the increased risk associated with embarking upon a pregnancy when severe or

morbid obesity and somehow also underweight are present,

and shows that this group of women need to be regarded as

high risk when counseling and risk assessment is done in the

prenatal clinic. For this, all pregnant women should have their

weight and height measured using appropriate equipments,

and their BMI calculated at the first prenatal booking visit. It

has also been recommended that midwives, general practitioners, and doctors should inform mothers about how to

recognize early warning signs of complications, especially

when they are obese.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of

interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and

writing of the paper.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global database on body mass index.

Available from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage

intro_3.html

2. World Health Organization. Overweight and obesity. Factsheet

no.311. Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/

fs311/en/index.html

3. Aranceta-Bartrinaa J, Serra-Majemb LL, Foz-Salac M, MorenoEsteband B, Grupo Colaborativo SEEDO. Prevalencia de

obesidad en Espana. Med Clin 2005;125: 460466.

4. Madan J, Chen M, Goodman E, Davis J, Allan W, Dammann O.

Maternal obesity, gestational hypertension, and preterm delivery.

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:8288.

5. Callaway LK, OCallaghan M, McIntyre HD. Obesity and the

hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy

2009;4:121.

6. Torloni MR, Betran AP, Daher S, Widmer M, Dolan SM,

Menon R, Bergel E, Allen T, Merialdi M. Maternal BMI and

preterm birth: a systematic review of the literature with metaanalysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:957970.

7. Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, Schmid SH, Dietz MC, Callaghan WM,

Curtis KM. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:223228.

8. Abenhaim HA, Kinch RA, Morin L, Benjamin A, Usher R. Effect

of prepregnancy body mass index categories on obstetrical and

neonatal outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;275:3943.

9. Catalano P, Ehrenberg H. The short- and long-term implications

of maternal obesity on the mother and her offspring. BJOG

2006;113:11261133.

10. Bhattacharya S, Campbell DM, Liston WA, Bhattacharya S.

Effect of body mass index on pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous

women delivering singleton babies. BMC Public Health 2007;7:

168176.

11. Horno M, Gacias JM, Rodriguez P, Ramon Y, Cajal J, Gonzalez

de Aguero R. La obesidad como factor de riesgo en el embarazo y

parto. Acta Gin 1985;42:361366.

12. Doherty DA, Magann EF, Francis J, Morrison JC, Newnham JP.

Pre-pregnancy body mass index and pregnancy outcomes. Int J

Gynaecol Obstet 2006;95:242247.

13. Gross T, Sokol RJ, King KC. Obesity in pregnancy: risks and

outcome. Obstet Gynecol 1980;56:446450.

14. Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris J, Regan L, Robinson S. Is maternal

underweight really a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome? A

population-based study in London. BJOG 2001;108:6166.

15. Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Krammer MS.

Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

N Engl J Med 1998;338:147152.

16. Denison F, Price J, Graham C, Wild S, Liston W. Maternal

obesity, length of gestation, risk of postdates pregnancy and

spontaneous onset of labour at term. BJOG 2008;115:720725.

17. Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock

CH, Saade G, Eddleman K, Carter SM, Craigo SD, et al.

Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate.

A population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2004;190:10911097.

18. Kliegman R, Gross T, Morton S, Dunnington R. Intrauterine

growth and postnatal fasting metabolism in infants of obese

mothers. J Pediatr 1984;104:601607.

19. Stapleton RD, Kahn JM, Evans LE, Critchlow CW, Gardella

CM. Risk factors for group B streptococcal genitourinary tract

colonization in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:

12461252.

20. Hakansson S, Kallen K. High maternal body mass index increases

the risk of neonatal early onset group B streptococcal disease.

Acta Paediatrica 2008;97:13861389.

21. Zhong Y, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Zhu F, Odibo AO. The

association between prepregnancy maternal body mass index and

preterm delivery. Am J Perinatol 2010;27:293298.

22. Salihu HM, Mbah AK, Alio AP, Clayton HB, Lynch O. Low prepregnancy body mass index and risk of medically indicated versus

spontaneous preterm singleton birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol 2009;144:119123.

23. Bianco AT, Smilen SW, Davis Y, Lopez S, Lapinski R,

Lockwood CJ. Pregnancy outcome and weight gain recommendations for the morbidly obese woman. Obstet Gynecol

1998;91:97102.

24. Perlow JH, Morgan MA, Montogomery D, Towers CV, Porto M.

Perinatal outcome in pregnancy complicated by massive obesity.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;167:958962.

25. Rodriguez P, Gonzalez R, Horno M, Ramon J. Peso materno

pregestacional y proceso reproductivo. Acta Ginecologica 1987;

44:4549.

26. Edwards LE, Alton IR, Barrada MI, Hakanson EY. Pregnancy in

the underweight woman. Course, outcome and growth patterns

of the infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1979;135:297302.

27. Cedergren MI. Maternal morbid obesity and the risk of adverse

pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:219224.

28. Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW,

Regan L, Robinson S. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome:

a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 2001;25:11751182.

29. Salihu HM, Lynch O, Alio AP, Mbah AK, Kornosky JL, Marty

PJ. Extreme maternal underweight and feto-infant morbidity

outcomes: a population-based study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal

Med 2009;22:428434.

30. Kalk P, Guthmann F, Krause K, Relle K, Godes M, Gossing G,

Halle H, Wauer R, Hocher B. Impact of maternal body mass

index on neonatal outcome. Eur J Med Res 2009;14:216222.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsDe la EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bmi PregnancyDocument11 paginiBmi PregnancyLilik AnggrainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 08 AimukhametovaDocument10 pagini08 AimukhametovahendraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Informe 10Document8 paginiInforme 10karen paredes rojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetic MaternlaDocument4 paginiDiabetic MaternlaAde Gustina SiahaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Pregnancy Weight Gain and The Risk of Placental AbruptionDocument9 paginiMaternal Pregnancy Weight Gain and The Risk of Placental AbruptionMuhammad Aulia KurniawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors for Macrosomia and Labor OutcomesDocument8 paginiRisk Factors for Macrosomia and Labor OutcomesKhuriyatun NadhifahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jur DingDocument8 paginiJur DingDeyaSeisoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pregnant Women With Morbid Obesity: Pregnancy and Perinatal OutcomesDocument6 paginiPregnant Women With Morbid Obesity: Pregnancy and Perinatal OutcomesVince Daniel VillalbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asuhan MaternalDocument4 paginiAsuhan Maternaljust FlowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleDocument5 paginiMaternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleKristine Joy DivinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Implications of Early Pregnancy Obesity On Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal Health PDFDocument7 paginiImplications of Early Pregnancy Obesity On Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal Health PDFAndhika Dimas AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research ArticleDocument8 paginiResearch Articlemohamad safiiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prematurity Maltese IslandsDocument12 paginiPrematurity Maltese IslandsIgor KnyazevÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obesity in Pregnancy - UPTO DATEComplications and Maternal Management - UpToDateDocument43 paginiObesity in Pregnancy - UPTO DATEComplications and Maternal Management - UpToDateCristinaCaprosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Obesity, Length of Gestation, Risk of Postdates Pregnancy and Spontaneous Onset of Labour at TermDocument6 paginiMaternal Obesity, Length of Gestation, Risk of Postdates Pregnancy and Spontaneous Onset of Labour at TermEdita Janet Yupanqui FlorianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurding (Autosaved)Document12 paginiJurding (Autosaved)Clara Elitha PaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Write UpDocument5 paginiCase Write UpAisyah Hamdan100% (1)

- Maternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019Document1 paginăMaternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019heidi leeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal ViolenceDocument6 paginiJurnal ViolenceIris BerlianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Maternal Weight Gain On Birth Weight: A Gestational Diabetes CohortDocument9 paginiInfluence of Maternal Weight Gain On Birth Weight: A Gestational Diabetes Cohortمالك مناصرةÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Obesity, Gestational Hypertension, and Preterm DeliveryDocument8 paginiMaternal Obesity, Gestational Hypertension, and Preterm DeliveryGheavita Chandra DewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2001 - Rev Saude PublDocument6 pagini2001 - Rev Saude PubllbnucciÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vol. 9 No. 2 Desember 2018Document13 paginiVol. 9 No. 2 Desember 2018AnissaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obesidad en El EmbarazoDocument17 paginiObesidad en El Embarazodianaarias1703Încă nu există evaluări

- Obesidad y EmbarazoDocument5 paginiObesidad y EmbarazolandabureÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Implications of Obesity On Pregnancy Outcome 2015 Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproductive MedicineDocument4 paginiThe Implications of Obesity On Pregnancy Outcome 2015 Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproductive MedicineNora100% (1)

- ACOG Committee Opinion On Weight Gain in PregnancyDocument0 paginiACOG Committee Opinion On Weight Gain in PregnancyKevin MulyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Obesity On Pregnancy and Its Outcome in The Population of Oman, Seeb ProvinceDocument12 paginiThe Effect of Obesity On Pregnancy and Its Outcome in The Population of Oman, Seeb ProvinceHazley ZeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Screening and Outcomes: Original Investigation 25Document5 paginiGestational Diabetes Mellitus Screening and Outcomes: Original Investigation 25Eduardo SasintuñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BMI in PregnancyDocument4 paginiBMI in PregnancyCitra KristiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Obesity Class I-III Gestational Weight GaDocument8 paginiMaternal Obesity Class I-III Gestational Weight GaAbdirahman Yusuf AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Parity in The Mode of DeliveryDocument11 paginiThe Role of Parity in The Mode of DeliveryKanuyasa GekzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weight: Maternal Body and Pregnancy Outcomel'2Document1 paginăWeight: Maternal Body and Pregnancy Outcomel'2Sary ArisazÎncă nu există evaluări

- BMJ 333 7579 Prac 01159Document4 paginiBMJ 333 7579 Prac 01159Neky KuntjoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Denison2008 PDFDocument6 paginiDenison2008 PDFKarolus KetarenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nej Mo A 1509819Document10 paginiNej Mo A 1509819Fhirastika AnnishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandaniDocument23 paginiTugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandanianisFitrihandani anisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes y Embarazo Tipo2 PDFDocument3 paginiDiabetes y Embarazo Tipo2 PDFFRM2012Încă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Birth Weight On Adverse Obstetric.20 PDFDocument6 paginiEffect of Birth Weight On Adverse Obstetric.20 PDFTriponiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Associated With Fetal Macrosomia: ObjectiveDocument10 paginiFactors Associated With Fetal Macrosomia: ObjectiveAdib FraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Embarazo MultipleDocument15 paginiEmbarazo MultipleLina E. ArangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lactancia CancerDocument7 paginiLactancia Cancerronaldito15Încă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes Mellitus and Pregnancy: Chapter OutlineDocument21 paginiDiabetes Mellitus and Pregnancy: Chapter OutlineqalbiÎncă nu există evaluări

- D'Souza-2019-Maternal Body Mass Index and PregDocument17 paginiD'Souza-2019-Maternal Body Mass Index and PregMARIATUL QIFTIYAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes During Pregnancy: The Effect of Body Mass Index on Composite MorbidityDocument8 paginiDiabetes During Pregnancy: The Effect of Body Mass Index on Composite MorbidityLinda Sekar ArumÎncă nu există evaluări

- First-Trimester Prediction of Gestational Hypertension Through The Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis of The Body CompositionDocument6 paginiFirst-Trimester Prediction of Gestational Hypertension Through The Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis of The Body Compositionppdsobginunsrijan23Încă nu există evaluări

- Fetal Macrosomia UptodateDocument22 paginiFetal Macrosomia UptodateWinny Roman AybarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity atDocument6 paginiMaternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity attaufik perdanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contribution of Maternal Overweight and Obesity To The Occurrence of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesDocument8 paginiContribution of Maternal Overweight and Obesity To The Occurrence of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesMichael ThomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Large For Gestational Age Newborn - UpToDateDocument17 paginiLarge For Gestational Age Newborn - UpToDateFernando Kamilo Ruiz ArévaloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Threatened Abortions On Pregnancy OutcomesDocument6 paginiThe Effects of Threatened Abortions On Pregnancy OutcomesfrankyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malformaciones Por Diabetes y ObesidadDocument8 paginiMalformaciones Por Diabetes y ObesidadKaren LeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of inadequate weight gain in overweight and obese pregnant womenDocument3 paginiEffect of inadequate weight gain in overweight and obese pregnant womenainindyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal Waist To Hip Ratio Is A Risk Factor For Macrosomia: EpidemiologyDocument7 paginiMaternal Waist To Hip Ratio Is A Risk Factor For Macrosomia: EpidemiologyKhuriyatun NadhifahÎncă nu există evaluări

- J of Obstet and Gynaecol - 2022 - La Verde - Incidence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Before and After The Covid 19Document6 paginiJ of Obstet and Gynaecol - 2022 - La Verde - Incidence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Before and After The Covid 19the OGs. 96Încă nu există evaluări

- Pattern of Glucose Intolerance Among Pregnant Women With Unexplained IUFDDocument5 paginiPattern of Glucose Intolerance Among Pregnant Women With Unexplained IUFDTri UtomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gestiational DMDocument6 paginiGestiational DMTiara AnggianisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Body Mass Index On The Incidence of Preterm LabourDocument6 paginiInfluence of Body Mass Index On The Incidence of Preterm LabourRizky MuharramÎncă nu există evaluări

- V14n3ao5 PDFDocument6 paginiV14n3ao5 PDFDANIELA STEFANIA MERA CORALÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Day Destination KeteranganDocument2 paginiNo Day Destination KeteranganAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maurice Nicoll The Mark PDFDocument4 paginiMaurice Nicoll The Mark PDFErwin KroonÎncă nu există evaluări

- ITINDocument3 paginiITINAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Reading 1 A. Deza FaristaDocument9 paginiJournal Reading 1 A. Deza FaristaAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Day Destination KeteranganDocument2 paginiNo Day Destination KeteranganAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Absensi SeminarDocument9 paginiAbsensi SeminarAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ITENERARYDocument2 paginiITENERARYAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schengen Visa Application January2017Document3 paginiSchengen Visa Application January2017Meiliana AnggeliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Absens IDocument16 paginiAbsens IAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ContentServer 52Document7 paginiContentServer 52Achmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FishboneDocument1 paginăFishboneAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asma LuluDocument25 paginiAsma LuluBrenda KarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Referat Gna DezaDocument37 paginiReferat Gna DezaAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orbital Lymphoma Diagnostic TreatmentDocument7 paginiOrbital Lymphoma Diagnostic TreatmentAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Azithromycin Pulse Therapy Effective in Acne TreatmentDocument3 paginiAzithromycin Pulse Therapy Effective in Acne TreatmentreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- ContentServer 51Document6 paginiContentServer 51Achmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topical Corticosteroid Vs Oral Zinc-Topical Corticosteroid in Patients With VitiligoDocument5 paginiTopical Corticosteroid Vs Oral Zinc-Topical Corticosteroid in Patients With VitiligoAan AnharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypertension 2013 Li 873 9aaaaaDocument8 paginiHypertension 2013 Li 873 9aaaaaAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lim FomaDocument7 paginiLim FomaAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seminar Pre-Eclamsi PDFDocument14 paginiSeminar Pre-Eclamsi PDFLydia Fe SphÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maat 09 I 1 P 10Document3 paginiMaat 09 I 1 P 10Achmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal BMI's impact on pre-eclampsia phenotypeDocument7 paginiMaternal BMI's impact on pre-eclampsia phenotypeAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weight Gain Recommendations in PregnancyDocument4 paginiWeight Gain Recommendations in PregnancyEirna Syam Fitri IIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Publication 519Document7 paginiPublication 519Achmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ContentServer 37.ASPaaaaaDocument6 paginiContentServer 37.ASPaaaaaAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Screen para Hie Doppler y MarcadoresDocument8 paginiScreen para Hie Doppler y MarcadoresAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutritional Status Among Women With Pre-Eclampsia and Healthy Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women in A Latin American CountryDocument7 paginiNutritional Status Among Women With Pre-Eclampsia and Healthy Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women in A Latin American CountryAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yclnu1789 PDFDocument14 paginiYclnu1789 PDFAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PreeDocument6 paginiPreeAchmad Deza FaristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re - SkinDocument371 paginiRe - SkinCharles LancasterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Placenta PreviaDocument24 paginiManagement Placenta PreviaMuhammad RifaldiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Attitudes to Abortion in America from 1800-1973Document16 paginiAttitudes to Abortion in America from 1800-1973ittoiram setagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dwnload Full Introducing Comparative Politics Concepts and Cases in Context 4th Edition Orvis Test Bank PDFDocument35 paginiDwnload Full Introducing Comparative Politics Concepts and Cases in Context 4th Edition Orvis Test Bank PDFdopemorpheanwlzyv100% (12)

- Complications in PregnancyDocument81 paginiComplications in PregnancyTia TahniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antepartum CareDocument20 paginiAntepartum Careapril jholynna garroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acknowledgement Maternity Benefit With ATDDocument2 paginiAcknowledgement Maternity Benefit With ATDAnthony Carl PS Hortilano100% (2)

- Challenges To The Implimentation of Reproductive Health Services in NigeriaDocument66 paginiChallenges To The Implimentation of Reproductive Health Services in NigeriaTeslim Raji0% (1)

- Biochemical Methods ObgDocument25 paginiBiochemical Methods ObgRupali AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocument22 paginiAmniotic Fluid EmbolismJay Marie GonzagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doh Programs Related To Family Health 2Document19 paginiDoh Programs Related To Family Health 2AnonymousTarget100% (1)

- Health Education For Record BookDocument24 paginiHealth Education For Record BookRoselineTiggaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Municipal Ordinance No. 04-2012Document6 paginiMunicipal Ordinance No. 04-2012JayPardinianNuyda100% (1)

- Ebewe Ebetrex PatientenbroschüreDocument11 paginiEbewe Ebetrex PatientenbroschüreferianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCN QUIZ With Rationale 60ptsDocument16 paginiMCN QUIZ With Rationale 60ptsKyla CapituloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intrauterine Growth RestrictionDocument4 paginiIntrauterine Growth RestrictionFate ZephyrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obs ClerkingDocument3 paginiObs ClerkingEbrahim Adel Ali AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 First Trimester UltrasonographyDocument17 pagini1 First Trimester UltrasonographyClaudia Paola Salazar SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neral Information II. HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS: Patient ExperiencedDocument10 paginiNeral Information II. HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS: Patient ExperiencedBianca Watanabe - RatillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fendo 13 967102Document9 paginiFendo 13 967102Vilma Gladis Rios HilarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paediatric NP FormDocument2 paginiPaediatric NP FormBOWEN TLCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marmot Wilkonson - The Solid FactsDocument31 paginiMarmot Wilkonson - The Solid FactsLavinia BaleaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preterm Labor: Prevention and Nursing Management,: 3rd EditionDocument59 paginiPreterm Labor: Prevention and Nursing Management,: 3rd Editionshaynie07Încă nu există evaluări

- Handbook For ASHA FacilitatorsDocument72 paginiHandbook For ASHA FacilitatorsachintbtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hematologic DisordersDocument30 paginiHematologic DisordersUday Kumar100% (1)

- Changes in Central Corneal Thickness in Healthy Pregnant Women-A Clinical StudyDocument3 paginiChanges in Central Corneal Thickness in Healthy Pregnant Women-A Clinical StudyIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- PROM Management and OutcomesDocument6 paginiPROM Management and OutcomesRayhan AlatasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ifa Didaa OgbeDocument1.256 paginiIfa Didaa Ogbemarco91% (54)

- Guideline ACOG Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy PDFDocument7 paginiGuideline ACOG Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy PDFyosua simarmataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pregnancy in ALSDocument9 paginiPregnancy in ALSAnonymous gSASKFÎncă nu există evaluări