Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A Companion To Crime Fiction - Agatha Christie - RESÚMEN

Încărcat de

Paulina EckartTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Companion To Crime Fiction - Agatha Christie - RESÚMEN

Încărcat de

Paulina EckartDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Agatha Christie (18901976)

For the greater length, Agatha Christie has been praised as an

ingenious puzzle-plotter. The golden age whodunit presents all

the clues needed to solve the murder, alongside a plethora of red

herrings to confuse the issue. Typically, it involves a closed

community of suspects (a train, a girls school, a village) most of

whom could be the murderer, as revealed through the process of

the detection. The pleasure of such a text is in trying to solve the

puzzle by analyzing all the information and arriving at the murderer

before the unmasking in the denouement.

And the narrative is inclusive with regards to the reader. Here

the reader is being addressed and invited to engage in the puzzle

by a supremely readerly narrative.

This combination of pleasurable activity in the reader and

ingenious plot-twists has proved phenomenally successful. For the

majority of the 20th century the critical consensus has been that

Christies plotting was her major claim to fame, since her texts

presented a cosy, conservative Englishness inhabited by stock

characters in a middle-class community, which is restored to order

by the elimination of the murderer.

F example, one of Christies narrative tropes is her manipulation

of cultural stereotypes: the major uttering imperialist views, the old

maid distrustful of young people, the nurturing nurse companion.

The texts deploy these stereotypes against the reader and the texts

investigator, invoking erroneous prejudices that blind them to the

more complex masked depths. Rather than invoke these stock

characters, Christie examines how her characters masquerade

within the conventional expectations, thereby reconfiguring the

instability and slipperiness of social identities.

York argues that while Christies texts are not postmodern, since

the novels close with the presentation of a truth, they do revel in

playing with the seductive power of the perspectives we take for

granted.

Christies use of the generic format is not formulaic either, but

similarly parodic and playful. Although Christie disobeyed the

rules of golden age fiction, she practiced a playful deconstruction

rather than wholesale destruction. Christies ability to critique selfreflexively the genres conventions points to a complex engagement

with the development of the golden age genre.

Christies murderers do not lurk out there in the unknown

urbanized world of crime but are ensconced within the circle of

friends and family. Surely this is more destabilizing to any concepts

of the known and safe?

Christies texts assume that anyone can be a murderer, no one is

exempt, no one totally to be trusted. The detective story is

something of a masquerade. Setting false trails for the reader and

presenting them with what is not as it might appear, [it] has at its

heart duplicity and performance. It is a duplicity that

determined to fool the reader as an effective whodunnit.

Christie portrayed, and in a sense foresaw a new kind of crime

that would lie beyond the detectives control

By the end of World War II, many of Christies cases are more

motiveless and less comforting in their denouement, for all that the

killer is apprehended or punished. Christies 68 novels have a

variety of detectives but she is most closely associated with three

enduring serial detectives. Poirot and Miss Marple, and Beresford

novels, which are usually categorized as thrillers rather than

detective novels. Christie herself differentiated between them,

seeing the former as more pleasurable and less rigorous to write,

but the Beresford series and the other thrillers in fact contain some

of Christies most interesting dissections of gender, cultural

change, and social instability.

Poirot

Hercule Poirot is the longest running of Christies detectives,

introduced in her first novel,

He is a parody of the male myth; his name implies his satirical

status: he is a shortened Hercules and a poirot a clown. He

is narcissistic, emotive, feline, apparently irrational, eccentric,

quixotic, obsessed with the domestic, and socially other in

that he is a Belgian. ... He is a feminine hero.

In creating the detective as foreigner in Styles - Christie initially

developed the stereotype of otherness. Poirots effete correctness

of attire is deliberately linked to an ordered thought-process that

metonymically also becomes inappropriate for English heroic

masculinity. Tidiness of dress and of domestic surroundings links

via its foreign otherness to femininity in Poirot. However, the

character does not long remain outlandish.

By the 1930s, Poirots behavior is less alien, as his tidiness is

linked to the clean lines of modernist interiors and his penchant

becomes both more familiar and more fashionable. This is a positive

attempt to think through the cultural possibilities for a new

masculinity after the horrors of World War I.

Rowland links this less heroic masculinity to the burgeoning

form of the golden age puzzle plot in Christie, associating the

absence of an autocratic characterization with the formal aspects of

a readerly text.

Poirot, in the prolific interwar years, predominates as Christies

chosen detective. The detectives investigation forms the major part

of the narrative, sifting through all the relevant clues with

periodical recapitulations of the more important details.

Simultaneously the detective relies on his knowledge of psychology

in relation to the type of killing involved. While he assumes

everyone is capable of murder, Poirot is determined that no one

could commit a murder outside of their character, and dismisses

false confessions on this very ground.

It is true that the Poirot of the later novels evidences a less

confident grasp of the British 1960s and his out-of-datedness may

have influenced Christies choice to deploy him less often.

Poirot s overweening pride in his success, his concern for his

immaculate appearance, are important parts of his characterization

and though they are modulated through the 50 years from alien to

familiar, they always remain because they are a necessity of his

characterization.

These human fallibilities, seen through others amused eyes,

inject an important element of humor into the Poirot texts that is

often absent from the Miss Marple novels.

Miss Marple

Where Poirot is the foreign outsider, Miss Marple is the village

insider, conversant with all the community. The literary antecedent

to Miss Marple, the character of the nosy old spinster with nothing

better to do than spy on her neighbors. However, then Christie

initially creates the elderly spinster, the sister of the narrator who

enjoys amateur detective, subsequently recognizing the characters

potential as a series detective.

Miss Marple is a bourgeois character, living frugally on an annuity,

though still able to employ a maid and then, as the social mores

change, a daily help and, finally, as her health deteriorates, a livein companion. Where Poirot uses his foreignness to his own

advantage, subtly exaggerating it to misguide English characters

into dismissing his acumen, Miss Marple manipulates the sexist and

ageist prejudices about old ladies being worthless to society,

lacking in intellectual ability and outmoded in their assumptions

and expectations, adopting the persona society expects as effective

camouflage.

Marple is transformed from a rather waspish introduction to a

gentler, mellower figure with pink cheeks and twinkling blue eyes,

and then to a more vengeful detective in the final novels, taking

pleasure in the fact that the culprit will be punished Poirot tends to

engage in detection to show off his abilities and because he

disagrees with murder, while Miss Marple sees a more personal

affront in the killings.

The Marple plots stress mystification rather than deduction This

closed, less playful, invitation to engage in the narrative game

perhaps helps to create the more serious tone of her series. Marple

stories do not offer the reader such overt clues.

Cultural prejudices are dismantled to demonstrate how, behind

the fluffy, frail exterior and the rather meandering, inconsequential

talk, is an astute, shrewd, and knowledgeable woman whose

expertise places her in the center of social occurrences, rather than

at the excluded margins. Her characterization quietly challenges

and rewrites the expectations of women of a certain age who are

unmarried and live alone.

Miss Marples main process of detection has some similarities to

Poirots use of psychology, although, since she classifies

characters into types, it is more rigid.

Thrillers

Christies thrillers were less rigorous novels to write, although they

also have similarities in their quest to unearth the villain veiled

behind the array of acquaintances and suspects. In both, Tommy

and Tuppence Beresford, Christies examination of the social

expectations of femininity and the array of available cultural

formations becomes even more overt than in the Poirot and Marple

series.

Christie often included romance plots in her detective fiction,

allowing Poirot and Marple to preside over denouements that not

only involve apprehending the culprit but also bring together the

young lovers in a dual - facetted happy ending. In the thrillers,

romance becomes more central and often proves the driving

impetus for the action

The real interest of these novels, is in the exploratory destabilizing of gendered expectations in the characterization.

Christie created a new genre of thriller in the comedyadventure.

A major part of the revisioning of Christie- fiction has come from

critics interested in gender. The earlier view of Christies

characters as stock stereotypes ignores the whole range of

unexpected persons, from sympathetic unmarried mothers and

mistresses to lesbian couples. Christie wrote over a period of 50

years and during this period her writing reflects on and explores

the cultural changes occurring between the 1920s and the 1970s.

Detective fiction, proves an ideal process for a quiet exploration of

how these changes impact on character and cultural expectation.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- How Agatha Christie Takes Our Attention Away From Roger As The Potential MurdererDocument3 paginiHow Agatha Christie Takes Our Attention Away From Roger As The Potential MurdererAnushka Euphony100% (1)

- Custody of The Pumpkin NotesDocument3 paginiCustody of The Pumpkin NotesRaniaKaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Christie - B.A. - ThesisDocument43 paginiA. Christie - B.A. - ThesisDonato PaglionicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 Agatha Christie Festival - LowresDocument20 pagini2013 Agatha Christie Festival - LowresliteratureworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agatha Christie: Five Little PigsDocument13 paginiAgatha Christie: Five Little PigsAnnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Adventure of The Clapham Cook - Agatha ChristieDocument3 paginiThe Adventure of The Clapham Cook - Agatha ChristieVerónica QuartucciÎncă nu există evaluări

- Murder On The Orient ExpressDocument1 paginăMurder On The Orient ExpressYamila AsisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Death On The Nile Characters Listed With DescriptionsDocument2 paginiDeath On The Nile Characters Listed With DescriptionsSmit100% (1)

- 4.50 From Paddington - WikipediaDocument15 pagini4.50 From Paddington - WikipediaNichu's VLOGÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tale of Two Cities Historical ApproachDocument13 paginiA Tale of Two Cities Historical ApproachAnonymous nMSPrgHdtOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sherlock Holmes-The Mystery of The Boscombe Pool - BilingueDocument37 paginiSherlock Holmes-The Mystery of The Boscombe Pool - BilingueСергей Фисенко100% (1)

- Murder On The Orient Express Study Guide Part IDocument6 paginiMurder On The Orient Express Study Guide Part Iapi-239423136Încă nu există evaluări

- Agatha ChristieDocument2 paginiAgatha Christienicolas100% (1)

- Unit-2 - Agatha ChirstieDocument26 paginiUnit-2 - Agatha ChirstieDevinder100% (1)

- Agatha Christie Dementia Study PDFDocument5 paginiAgatha Christie Dementia Study PDFKeith userÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar Introduction Power PointDocument12 paginiJulius Caesar Introduction Power PointShraddha Maheshwari100% (1)

- Agatha Christie The Murder of Roger Ackroyd PDFDocument20 paginiAgatha Christie The Murder of Roger Ackroyd PDFNooreen zenifa RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Time For Murder: Didactic ProjectDocument24 paginiTime For Murder: Didactic ProjectcarmonafjÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Murder On The Orient ExpressDocument15 paginiThe Murder On The Orient ExpressMuhAshabulKahfiArafahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detective Fiction Assignment The Historiography of Detective FictionDocument5 paginiDetective Fiction Assignment The Historiography of Detective FictionShivangi DubeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Detectives in Agatha Christie's NovelsDocument4 paginiThe Detectives in Agatha Christie's NovelsmikaelaarianneÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Science of Agatha Christie: The Truth Behind Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, and More Iconic Characters from the Queen of CrimeDe la EverandThe Science of Agatha Christie: The Truth Behind Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, and More Iconic Characters from the Queen of CrimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curious Incident and Detective Fiction ArticleDocument4 paginiCurious Incident and Detective Fiction Articleapi-331074548Încă nu există evaluări

- Murder of Roger Ackroyd Discussion QuestionsDocument2 paginiMurder of Roger Ackroyd Discussion QuestionsSneha Pradhan75% (4)

- English Question AnswersDocument7 paginiEnglish Question AnswersMansi rajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seeds of An Evolution - Crime FictionDocument3 paginiSeeds of An Evolution - Crime FictionbleakfamineÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Moment on the Edge: 100 Years of Crime Stories by WomenDe la EverandA Moment on the Edge: 100 Years of Crime Stories by WomenEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (45)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Mystery and Detective Fiction: Agatha ChristieDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Mystery and Detective Fiction: Agatha ChristieÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Agatha Christie Revolutionized MurderDocument4 paginiHow Agatha Christie Revolutionized MurderbenefryÎncă nu există evaluări

- How to Write Killer Historical Mysteries 2022 EditionDe la EverandHow to Write Killer Historical Mysteries 2022 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghosts from the Library: Lost Tales of Terror and the SupernaturalDe la EverandGhosts from the Library: Lost Tales of Terror and the SupernaturalEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- The A.B.C. Murders by Agatha ChristieDocument4 paginiThe A.B.C. Murders by Agatha ChristieajaydeepuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Popular Literature Kashish AnswerDocument4 paginiPopular Literature Kashish AnswerAnanya 2096Încă nu există evaluări

- And There Were NoneDocument4 paginiAnd There Were Nonedilawar sajjadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit & ObsessionDe la EverandUnspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit & ObsessionEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (49)

- Agatha Christie Collection - 3 Novels And 25 Short StoriesDe la EverandAgatha Christie Collection - 3 Novels And 25 Short StoriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women of Mystery: The Lives and Works of Notable Women Crime NovelistsDe la EverandWomen of Mystery: The Lives and Works of Notable Women Crime NovelistsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

- A Study of Five Detective Novels by Dorothy L. SayersDocument80 paginiA Study of Five Detective Novels by Dorothy L. Sayersvanveen1967Încă nu există evaluări

- Paul Auster City of GlassDocument7 paginiPaul Auster City of GlassAndrea Gyülvészi100% (1)

- After the Funeral: A Hercule Poirot Mystery: The Official Authorized EditionDe la EverandAfter the Funeral: A Hercule Poirot Mystery: The Official Authorized EditionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (38)

- Ghosts of A Brutal Past: Jane Smiley The GuardianDocument3 paginiGhosts of A Brutal Past: Jane Smiley The GuardianasdaasdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles P. Mitchell - Complete H.P. Lovecraft FilmographyDocument433 paginiCharles P. Mitchell - Complete H.P. Lovecraft FilmographyAndrew Clark100% (3)

- No Description AnswerDocument5 paginiNo Description AnswerAriola ErwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhoplex Ec-1791 QsDocument7 paginiRhoplex Ec-1791 QsA MahmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaDocument20 paginiDe Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaKateryna SorokaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speech For English CarnivalDocument5 paginiSpeech For English CarnivalshammalabsreetharanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cruise Ship Song List (2021)Document7 paginiCruise Ship Song List (2021)EntonyKarapetyan100% (4)

- Drinking PDFDocument32 paginiDrinking PDFPencils of PromiseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emily - EnglishDocument7 paginiEmily - Englishpetalouda1980Încă nu există evaluări

- ENGLISHDocument2 paginiENGLISHblack stalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plywood ScooterDocument7 paginiPlywood ScooterJim100% (4)

- T.V. & Video ConnectorsDocument7 paginiT.V. & Video ConnectorsEldie TappaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 898 Product Tech Data SheetDocument1 pagină898 Product Tech Data SheetPowerGuardSealersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ear Training EssentialsDocument85 paginiEar Training EssentialsJuan Ramiro Pacheco Aguilar100% (1)

- Partimento-Fugue - The Neapolitan Angle PDFDocument43 paginiPartimento-Fugue - The Neapolitan Angle PDFPaul100% (1)

- DVP 505A User GuideDocument22 paginiDVP 505A User GuideMillsElectricÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hermitage HotelDocument10 paginiHermitage HotelBharata Hidayah AryasetaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1984 Powerplay QuotesDocument16 pagini1984 Powerplay QuotesGa YaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coalhurst Elementary Kindness Program by Sareena Lakhu and Katelyn ArikDocument13 paginiCoalhurst Elementary Kindness Program by Sareena Lakhu and Katelyn Arikapi-539510253Încă nu există evaluări

- Section A-A Detail of Rubble Paving at Wing Wall: 60Mm Thk. Wearing CourseDocument1 paginăSection A-A Detail of Rubble Paving at Wing Wall: 60Mm Thk. Wearing CoursesathiyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 Fashion CentersDocument48 paginiChapter 4 Fashion CentersJaswant Singh100% (1)

- British Women TranslatorsDocument14 paginiBritish Women Translatorscatrinel_049330Încă nu există evaluări

- 201434662Document88 pagini201434662The Myanmar TimesÎncă nu există evaluări

- PREPARE 3 Grammar Plus Unit 01Document2 paginiPREPARE 3 Grammar Plus Unit 01Narine HovhannisyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- GP Welcome Tune List 2015Document2 paginiGP Welcome Tune List 2015AlexÎncă nu există evaluări

- CJLyes ColosseumDocument9 paginiCJLyes ColosseumAtu MsiskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barbeau, Maurius. Totem Poles (Vol. 2)Document25 paginiBarbeau, Maurius. Totem Poles (Vol. 2)IrvinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thoughts & Life of A LegendDocument213 paginiThoughts & Life of A LegendDrDaniel Victory100% (2)

- MIL - L10 - People in The MediaDocument3 paginiMIL - L10 - People in The Mediaclain100% (1)

- The Judge's HouseDocument31 paginiThe Judge's HousekuroinachtÎncă nu există evaluări

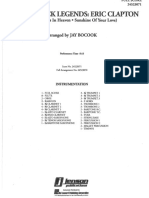

- Pop and Rock Legends Eric Clapton by Jay BocookDocument89 paginiPop and Rock Legends Eric Clapton by Jay Bocooklouish9175841100% (2)