Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

CH 08

Încărcat de

savyasachinTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CH 08

Încărcat de

savyasachinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

8

The Larynx:

Advanced Stage Disease

JOHN F. CAREW, MD

Of the 295,000 cases of cancer of the head and neck

accrued by the National Cancer Data Base over a 10year period, larynx was the most common site

accounting for more than 20 percent of all head and

neck cancers.1 Squamous cell carcinoma which arises

from the mucosa lining the larynx accounted for over

90 percent of all cancers in this site.2 In one of the

larger studies of patients with larynx cancer, 40 percent of patients presented with advanced stage disease

(stage III or IV).2 Despite the use of aggressive multimodality treatment in patients with advanced stage

cancer of the larynx, overall survival for these patients

ranges from 42 to 77 percent.214 As mentioned in the

section on early stage disease, other neoplasms such

as lymphomas, minor salivary gland tumors, mucosal

melanomas and sarcomas may affect this site,

although large series evaluating these specific

pathologies at this site are lacking in the literature.

Unless otherwise specified, squamous cell carcinomas of the larynx will be the subject of this chapter.

The larynx performs several unique and vital

functions related to phonation, breathing and swallowing, and the treatment of patients with neoplasms

of this organ requires consideration of these critical

functions. Specifically, the impact of therapeutic

options on both the extent as well as the quality of

life needs to be taken into account. As this section

focuses on advanced cancer of the larynx, most

treatment options involve multimodality therapy in

the form of either chemotherapy and radiation therapy or surgery and radiation therapy. The critical

decision, which continues to evolve, is selecting the

appropriate treatment for each individual patient.

156

Additionally, the optimal treatment plan which combines chemotherapy and radiation therapy with

regards to timing (sequential vs. concomitant), radiation fractionation, chemotherapeutic agents and

adjuvants remains undefined. In this section, the

diagnosis, treatment and outcome of patients with

advanced cancer of the larynx will be presented.

ANATOMY

While the basic anatomy of the larynx already has

been described in the section on early larynx cancer,

this section will highlight the critical points relevant

to treating patients with advanced cancers of the larynx. The majority of larynx cancers are found in the

glottic region (56%) followed by the supraglottic

region (41%), while tumors of the subglottic region

are relatively infrequent (1 to 2%) (Figure 81).2,15 It

is important to realize that tumors in these different

regions of the larynx have different clinical behaviors. Supraglottic tumors, for example, have a much

higher rate of occult and bilateral metastasis than

glottic primaries.10,16 The regional lymph nodes of

the neck in patients with advanced stage supraglottic tumors and clinically negative necks must therefore be addressed in treatment planning.

The connective tissue barriers which lie between

the mucosa and cartilaginous skeleton of the larynx,

namely the conus elasticus and quadrangular membrane, are critical to the understanding of patterns of

spread and clinical behavior of advanced cancers of

the larynx (Figure 82). These membranes provide a

barrier to the spread of cancer but are often breached

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

Supraglottic

41%

Glottic

56%

Subglottic

3%

Figure 81.

Site distribution of larynx cancers.

by advanced tumors (Figure 83).17 Once a tumor

has broken through these boundaries, it can spread

into the soft tissues of the neck as well as vertically

within the larynx.

Two regions that are deep to the quadrangular

membrane and conus elasticus are the preepiglottic

and paraglottic space. Advanced tumors often enter

these spaces when they transgress these connective

tissue barriers within the larynx and thus enter a

compartment where further spread is less hindered.

The preepiglottic space is bounded by the thyrohyoid membrane anteriorly, the valleculae superiorly,

the epiglottis posteriorly and the hyoid inferiorly.

This space is commonly involved by local spread of

supraglottic tumors. Once this space is involved, a

supraglottic tumor is staged as a T3.18 Tumors

157

involving this area can then spread into the soft tissues of the neck via the foramen in the thyrohyoid

membrane or inferiorly via the paraglottic space. In

some patients, however, a connective tissue barrier

separates the preepiglottic and paraglottic space.19

The paraglottic space is the compartment which

is bounded by the thyroid lamina laterally, the

conus elasticus medially-inferiorly and the quadrangular membrane and preepiglottic space medially-superiorly. Loose connective tissue and adipose tissue lying between thyroid lamina and the

connective tissue membranes of the larynx occupy

this space. This area is most commonly involved by

advanced glottic tumors. Once this compartment is

entered, tumors can spread relatively freely in a

superior and inferior direction, as well as outside

the confines of the larynx via the cricothyroid

membrane or the preepiglottic space. Involvement

of this space frequently results in decreased vocal

fold movement.

Cancers of the larynx can be classified as

advanced (stage III or IV) either by virtue of an

advanced primary tumor or by the presence of

regional lymph node metastasis. When regional

lymph node metastases are present they are

described by their location, number and size. The

location of the lymph nodes is described by levels in

the neck as illustrated in the chapter on neck metastasis. Levels II, III and IV are at highest risk for

lymph node metastasis from cancers in the larynx.

Figure 82. A, Sagittal section of larynx demonstrating the preepiglottic and B, coronal section of larynx

demonstrating the paraglottic space.

158

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

Diagnosis

Patients with advanced glottic cancers will present

with symptoms similar to patients with early glottic

cancers. As listed earlier these include hoarseness or

a change in the quality of voice, odynophagia, halitosis or otalgia. Not suprisingly the more ominous

symptoms, such as hemoptysis, dysphagia, airway

compromise and neck mass are more common in

advanced stage disease. Additionally, the supraglottic

and subglottic lesions tend to be less symptomatic

and their insidious growth results in a high percent of

patients presenting with advanced stage disease.

As mentioned earlier, adequate examination of

the larynx by use of the laryngeal mirror or a rigid

telescope or fiberoptic flexible nasopharyngoscope

is essential to staging and treatment planning (Figure 84).20 Critical in this evaluation is assessment

of the epicenter of the tumor, vocal fold mobility,

extra-laryngeal involvement and regional lymph

nodes in the neck. Although early tumors are often

adequately assessed by history and physical exam

alone, appropriate evaluation of advanced lesions

usually requires radiographic imaging to ascertain

the depth of the tumor involvement, preepiglottic

space extension, paraglottic extension, cartilage

involvement and extra-laryngeal spread. High-resolution CT scans with thin cuts through the larynx

usually give adequate information regarding these

aspects (Figure 85).21 Additionally, in patients with

necks which are difficult to assess clinically, radiographic evaluation may add information in establishing the regional lymph node status.

The staging of patients with advanced cancers of

the larynx is outlined in Table 81.18 As with other

sites in the head and neck, the complex anatomy in

this region makes accurate staging challenging. At

times, the location of the lesion appears to carry

more weight than the tumor burden. For example, a

relatively small tumor on the posterior aspect of the

larynx which involves the post-cricoid area will be

stage T3, while a bulky tumor replacing the

aryepiglottic fold, epiglottis and spilling down the

medial wall of the pyriform sinus will be staged a T2

as long as the vocal cord remains mobile. While survival has been related to both T stage and N stage, it

B

Figure 83. Whole organ sections showing tumor involving the

preepiglottic and paraglottic space.

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

is most profoundly affected by the nodal status of the

patient.2,10,11 It has long been known that regional

lymph node involvement in head and neck cancer

patients decreases survival by approximately 50 percent.10,11 The present staging system of the American

Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) groups both

patients with locally advanced tumors (T3N0) and

patients with regional lymph node metastasis (T1-

159

3N1) together into stage III.18 This may arbitrarily

group 2 subsets of patients together who have vastly

different prognoses. Both the stage as well as the

nodal status must thus be considered when interpreting results from the treatment of larynx cancer.

Just as there are ominous symptoms in patients

with advanced cancer of the larynx, there are also

several physical findings that are harbingers of clin-

D

Figure 84. Endoscopic view and assessment of a laryngeal cancer using the A-0; B-30; C-70; D-120 telescopes.

160

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

A

Figure 85. A, Axial CT of advanced laryngeal primary tumor

demonstrating paraglottic involvement and cartilage destruction but

without extension into the soft tissues of the neck. B, Axial CT of

advanced laryngeal primary tumor demonstrating cartilage destruction and extension into the soft tissues of the neck.

ically aggressive behavior. Extensive spread into the

soft tissues of the neck, involvement of the overlying

skin, regional lymph node metastases which are

fixed or limited in vertical mobility, and bulky disease low in the neck all suggest a poor prognosis.

Treatment Goals and Treatment

AlternativesThe Role

of Multidisciplinary Treatment

In the last 2 decades, 5-year survival of patients with

laryngeal cancer has not changed dramatically.22

Maximizing survival, therefore, continues to be the

ultimate goal in treating patients with advanced

stage larynx cancer. Recently, however, due to the

lack of improvement in survival, significant efforts

have been made to improve the quality of life in

these patients. Paramount to this is preservation of a

functional larynx. Toward this goal, treatment

options have been formulated with the hopes of

increasing laryngeal preservation without sacrificing survival. Multimodality treatment paradigms, in

the form of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical

salvage, has emerged as a viable treatment option

allowing anatomical preservation of the larynx without decreasing survival.3 Now that a method of

laryngeal preservation has been established, future

goals in treatment are directed at increasing both the

rate of laryngeal preservation and survival.

Factors Affecting Choice of Treatment

Factors affecting choice of treatment can be divided

into patient factors and tumor factors. As demonstrated in multiple clinical trials, survival is statistically equivalent in selected patients with advanced

cancer of the larynx who are treated with either

chemotherapy and radiation therapy or surgery and

radiation therapy.3,6,7,9,2325 Given this, patients who

wish to utilize a treatment paradigm that may preserve their larynx, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, should be given this nonsurgical option.

Alternatively, there is a cohort of patients who are of

the mindset that they would rather have all cancer

removed and would prefer surgery and radiation therapy, understanding that their ability to communicate

will be significantly affected. Finally, any patient

who is considering chemotherapy and radiation therapy as a treatment option must be reliable and must

enroll a multidisciplinary team experienced in treating patients with advanced cancer of the larynx.

Many tumor factors also contribute to the decision process in determining the optimal treatment

for each patient. If a tumor or lymph node metasta-

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

sis shows ominous clinical signs suggesting unresectability, then certainly a surgical option should

not be contemplated and consideration given to

chemotherapy and radiation therapy.26,27 A clinical

situation which is interesting but infrequent arises

when a patient presents with an early stage primary

lesion and clinically apparent regional lymph node

metastasis. In this situation several treatment options

exist. If the primary lesion is best treated by radia-

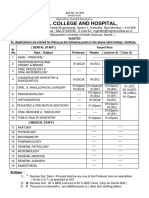

Table 8-1. AJCC STAGING OF CARCINOMA OF THE LARYNX

Supraglottis

T1: Tumor limited to one subsite of the supraglottis with normal

vocal cord mobility

T2: Tumor invades mucosa of more than one adjacent subsite

of the supraglottis or glottis or region outside the supraglottis (eg, mucosa of the base of tongue, valleculae, medial

wall of pyriform sinus) without fixation of the larynx

T3: Tumor limited to the larynx with vocal cord fixation and/or

invades any of the following: postcricoid area, preepiglottic

tissues

T4: Tumor invades through the thyroid cartilage, and/or extends

into the soft tissues of the neck, thyroid and/or esophagus

Glottis

T1: Tumor limited to the vocal cord(s) (may involve anterior or

posterior commissure) with normal vocal cord mobility

T1A: Tumor limited to one vocal cord

T1B: Tumor involves both vocal cords

T2: Tumor extends to the supraglottis and/or subglottis, and/or

with impaired vocal cord mobility

T3: Tumor limited to the larynx with vocal cord fixation

T4: Tumor invades through the thyroid cartilage and/or extends

to other tissues beyond the larynx (eg, trachea, soft tissues

of the neck, including thyroid, pharynx)

Subglottis

T1: Tumor limited to the subglottis

T2: Tumor extends to the vocal cord(s) with normal or impaired

mobility

T3: Tumor limited to the larynx with vocal cord fixation

T4: Tumor invades through the cricoid or thyroid cartilage

and/or extends to other tissues beyond the larynx (eg, trachea, soft tissues of the neck, including thyroid, esophagus)

Neck

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

N1: Ipsilateral lymph node metastasis 3 cm

N2: Lymph node metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node

> 3 cm and 6 cm, or in multiple lymph nodes none more

than 6 cm (including bilateral nodal metastasis)

N2A: Lymph node metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph

node > 3 cm and 6 cm

N2B: Lymph node metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph

nodes all 6 cm

N2C: Lymph node metastasis in bilateral or contralateral

lymph nodes all 6 cm

N3: Lymph node metastasis > 6 cm

161

tion therapy, one could consider a comprehensive

neck dissection followed by radiation therapy to the

primary site and the neck. Alternatively, if the primary lesion is best treated by a surgical approach,

one could consider a partial laryngectomy and neck

dissection with the addition of adjuvant radiation

therapy as indicated based on pathologic findings.

Of the most important factors in deciding the

optimal treatment are the characteristics of the primary tumor. Tumors which are endophytic, show

extensive cartilage invasion, involve the soft tissues

of the neck, or involve the airway to such an extent

that a tracheostomy is required, often demonstrate

aggressive clinical behavior and respond poorly to

treatment. Whether these patients fare better in a

surgical treatment arm as opposed to a nonsurgical

plan has yet to be substantiated in a randomized

prospective trial. The ideal treatment in these

patients, therefore, remains controversial. In such

patients, aggressive early surgical intervention will

improve the chances for locoregional control and

thus improve the quality of life that would otherwise

be significantly deteriorated with persistent or recurrent disease. Early aggressive surgical intervention

may not improve survival or risk of distant metastasis, but would certainly offer avoidance of airway

obstruction, asphyxiation or intractable pain.

Surgical Treatment

In the majority of patients with advanced primary

tumors of the larynx, the surgical treatment consists

of a total laryngectomy. It should be remembered,

however, that partial laryngectomy and conservational surgical procedures which preserve the function of the larynx may be options in selected

patients. As discussed in the section on early larynx

cancer, vertical partial, supraglottic partial and

supracricoid partial laryngectomies can be performed in carefully selected patients. In patients

with advanced lesions, however, the more extensive

partial laryngectomies are utilized more frequently

and even more selectively. These procedures,

although categorized in broad terms such as neartotal laryngectomy or supracricoid partial laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy, are usually individually

designed to adequately encompass each patients

162

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

particular tumor while sparing as much functional

tissue as oncologically feasible (Figure 86).2831

Appropriate management of the neck is critical

to maximizing survival in patients with advanced

cancer of the larynx. The treatment of the neck

depends in part on the treatment of the primary. If

the primary is to be treated by surgical means, then

an elective dissection of the lymph nodes at risk

should be planned in the clinically negative neck.

For a glottic lesion, the ipsilateral levels II to IV

should be cleared, while for a supraglottic lesion,

bilateral levels II to IV are at risk and should be dissected. If there is clinically apparent lymph node

metastasis in the neck and the primary is to be

treated by surgery, then a comprehensive neck dissection (levels I to V) should be performed.

B

Figure 86. Schematic diagram of two well-described voice-preserving, extended laryngeal procedures: A, supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidoepiglottopexy and B, supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy (dotted lines represent line of surgical excision).

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

Alternatively, if a patient with a clinically negative

neck is to be treated by chemotherapy and radiation

therapy to the primary lesion, the neck at risk should

also be treated electively by radiation therapy. A

somewhat more controversial situation exists if there

is a clinically positive neck and the primary is to be

treated by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The

options that exist include performing a comprehensive neck dissection prior to chemotherapy/radiation

therapy, performing a planned comprehensive or

selective neck dissection after chemotherapy/

radiation therapy or assessing response following

chemotherapy/radiation therapy and performing

appropriate neck dissection based on response. At

this time, data is lacking to substantiate an advantage

in any of these approaches and all are acceptable.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The appreciation of the psychosocial consequences

of total laryngectomy has been the impetus for the

development of treatment options which could preserve the larynx of patients with advanced stage larynx cancer. In the early 1990s, a prospective, randomized trial of patients treated at Veterans Affairs

Hospitals with stage III and stage IV squamous cell

carcinoma of the larynx, comparing conventional

treatment of surgery and postoperative radiotherapy,

with induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy was performed.3 In this study, patients in the

chemotherapy-radiation therapy (chemo/RT) arm

who did not display at least a 50 percent response to

induction chemotherapy, or who showed persistent

or recurrent disease following radiation, were salvaged with surgery. This landmark study demonstrated survivals which were not statistically different between treatment arms (68%), and allowed 64

percent of patients within chemo/RT arms to preserve their larynx.3 With the results of the Veterans

Affairs Larynx Cancer Study Group (VALCSG)

trial, the combination of induction chemotherapy

and radiation therapy has emerged as a treatment

option which allows preservation of the larynx in

nearly two-thirds of patients. Since this trial, many

other studies have been performed to confirm

chemo/RT as an effective treatment for patients with

advanced larynx cancer.6,7,9,2325,32

163

Sequelae, Complications and

their Management

Surgery and Radiotherapy

The complications associated with total laryngectomy can be divided into acute and chronic. The

acute complications include those related to surgery

and general anesthesia. These include bleeding,

infection, pneumonia and fistula. The most troublesome of these is the pharyngocutaneous fistula. The

fistula rate following total laryngectomy remains

relatively high, ranging from 8 to 22 percent.3335

Appropriate treatment of a pharyngocutaneous fistula requires early recognition and then wide opening of the wound with appropriate wound care. The

patient should stop all oral intake and an alternative

route of alimentation should be established. If significant carotid exposure is seen, then consideration

should be given to coverage with a regional flap to

afford carotid protection, especially in the setting of

previous radiation therapy. Often the fistula will

close spontaneously with aggressive wound care. In

those cases where it does not, local, regional and

even free flaps may be used to obtain closure.

The most common chronic complication of total

laryngectomy is stricture formation with dysphagia. It

is crucial to rule out recurrent tumor whenever a

patient develops new dysphagia or worsening dysphagia. This is usually best evaluated by endoscopy

with direct visualization of the mucosa of the

neopharynx. Preoperative esophagrams are often

helpful in defining the location and extent of stricture.

If a stricture is seen, it can usually be dilated, although

repeated treatments are often required. Ultimately, if

a stricture is unresponsive to these conservative measures, consideration can be given to free tissue transfer to reconstruct an adequate neopharynx.

The early sequelae of radiation therapy relate primarily to the acute tissue reactions with characteristic skin changes and mucositis. These are managed

symptomatically with oral hygiene and topical medications. The late sequelae of radiation therapy

include skin changes, xerostomia and, very rarely,

chondroradionecrosis of the laryngeal skeleton.

Xerostomia is treated symptomatically with oral

hygiene and humidification. In severe cases where

chondroradionecrosis profoundly impairs swallow-

164

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

ing and breathing, a total laryngectomy may need to

be performed to restore the ability to swallow.

Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy

Treatment protocols using chemo/RT to preserve

organ function have successfully demonstrated their

ability to anatomically preserve the larynx without

compromising survival. One aspect of these protocols that is often underappreciated is the functional

capacity of the retained organs. Few investigators

have clearly documented the functional sequelae of

chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Recently,

Lazarus retrospectively studied patients being

treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy and

found that 40 percent had swallowing difficulties.36

Clinical evidence of disorders in the pharyngeal

phase of swallowing has been demonstrated in

patients who have undergone chemotherapy and

radiation therapy for tumors of the upper aerodigestive tract. Specifically, reduced laryngeal closure,

reduced laryngeal elevation and reduced posterior

tongue base movement relative to age-matched controls has been documented.36 Certainly, patients who

successfully undergo chemo/RT treatments to preserve their larynx have a much improved quality of

life relative to patients requiring total laryngectomy.37 Nevertheless, it should be realized that

anatomic preservation does not always result in

functional preservation. Very rarely, total laryngectomy is performed in order to restore the ability to

swallow when a larynx is incompetent and nonfunctional but clinically free of cancer.

In addition to functional sequelae, chemotherapy

(specifically when given in combination with radiation therapy) has some definite toxicities. Toxicity

from induction chemotherapy has prevented 7 to 18

percent of patients from receiving a full course of

chemotherapy.3,4,6,8 Even mortality, as a result of

chemotherapy and radiation-related toxicity, has

been reported to range from 0.6 to 6 percent.3,59,25

Rehabilitation and Quality of Life

In the past, conventional treatment of advanced stage

laryngeal cancer consisted of surgery and postoperative external beam radiation. Surgical resection of the

majority of advanced stage laryngeal lesions con-

sisted of total laryngectomy with the resultant deleterious effects on deglutition, phonation and the creation of a permanent tracheostoma. The psychosocial

consequences of total laryngectomy have been well

studied.14,3739 Not suprisingly, quality of life measurements and psychosocial indicators are significantly affected by total laryngectomy. Although techniques for voice rehabilitation have improved, studies

have shown that the psychosocial effects of laryngectomy are as much related to loss of voice as they

are to other factors such as the necessity of a permanent tracheostoma.14,38,39 When the patients treated in

the Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group

were evaluated, an improved long-term quality of life

was seen in the cohort who were randomized to

chemotherapy and radiation therapy compared to

those treated by surgery and radiation therapy.37

Interestingly, this difference was primarily related to

freedom from pain, better emotional well-being and

lower levels of depression rather than the preservation of the ability to speak.

Nevertheless, several methods are available to

rehabilitate the ability of a patient to communicate

following total laryngectomy. Many patients are able

to acquire esophageal speech, in which air is swallowed and then used to create a voice. Approximately 2 decades ago a significant advance in the

rehabilitation of patients with laryngectomies took

place when the tracheoesophageal puncture was

developed.40 This is a relatively minor procedure

where a fistula is created between the trachea and

esophagus (Figure 87). A prosthesis with a oneway valve is placed into this fistula, which allows

the creation of a lung powered voice. In the motivated patient, this voice can be quite good.

Outcomes and Results of Treatment

Historically, surgery in the form of total laryngectomy

followed by adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy

has been the standard treatment for most patients with

advanced stage cancer of the larynx.1012,41,42 Additionally, selected patients with advanced stage larynx

cancer have been treated with definitive radiation

therapy alone.13,42,43 The results of these treatments

are summarized in Table 82 with 5-year survival

ranging from 54 to 91 percent.1013,4143

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

Figure 87.

Schematic diagram of tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP).

More recently, chemotherapy/radiation therapy

has evolved as an effective treatment for advanced

stage cancer of the larynx. A summary of results

from the various studies evaluating chemo/RT in the

treatment of patients with advanced stage laryngeal

cancer, with the goal of larynx preservation, are

listed in chronologic order in Table 83.39,25 In all

but one study, more than 90 percent of patients evaluated had stage III or IV disease. Most studies

included only those patients who would have

required a total laryngectomy if treated by conventional means with surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. Treatment results for patients treated with

chemo/RT in these studies are fairly consistent with

2-year survival ranging from 50 to 77 percent, lar-

Table 82. RESULTS OF CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

OF ADVANCED CARCINOMA OF THE LARYNX

Author

12

Kirchner

Harwood13

Harwood43

Yuen41

Year

No.

Type of

Therapy

1977

1979

1983

1984

308

353

410

192

50

100

65

116

65

S/RT

RT

RT

S

S/RT

RT

SRT

S/RT

SRT

Mendenhall42 1992

Nguyen11

Myers10

1996

1996

165

5 yr

Stage

Survival

III/IV (%)

(%)

100

54

66

100

100

100

100

100

100

5456*

70

57

77

91

74

63

68

62

Survival rates refer to disease-free survival when available, otherwise they

refer to overall survival.

* study included both laryngeal and non-laryngeal sites.

S = Surgery; RT = Radiation therapy; 2-year survival.

ynx preservation rates ranging from 64 to 79 percent, locoregional failure rates ranging from 20 to

33 percent and distant failure rates ranging from 8 to

21 percent.39,25 It should be noted, however, that

only one of these studies was limited only to patients

with laryngeal primaries,3 while the remainder of

the studies included patients with hypopharynx,

oropharynx, oral cavity and even paranasal sinuses

as sites of primary tumors.49,25 The majority of

these studies that included non-laryngeal sites did so

because surgical treatment of the primary would

have required total laryngectomy. The data presented

Table 83. RESULTS OF TREATMENT OF ADVANCED

CARCINOMA OF THE LARYNX UTILIZING

CHEMOTHERAPY AND RADIATION THERAPY

2 yr.

Type of

Stage

Survival

Therapy III/IV (%)

(%)

Author

Year

No.

Jacobs4

Demard5

1987

1990

30

50

C/RT

C/RT

100

64

Veterans Affairs

Larynx Group3

Pfister6

Karp7

Urba8

Clayman9

(includes data

from Shirinian)25

1991

166

166

13

14

8

26

52

C/RT

S/RT

C/RT

C/RT

C/RT

C/RT

S/RT

100

100

98

92

93

96

96

1991

1991

1994

1995

52*

74*

(Response

rate)

68

68*

77*

50*

75*

68*

81*

Survival rates refer to disease-free survival when available, otherwise they

refer to overall survival.

* Study included both laryngeal and non-laryngeal sites. C = chemotheapy;

S = surgery; RT = radiation therapy.

166

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

in this table refers, whenever possible, to the subset

of patients with laryngeal primaries, although this

information was not always available.

In several of these aforementioned studies, single

modality therapy in the form of definitive radiotherapy was utilized and yielded disease-specific survivals similar to those seen with the combination of

induction chemotherapy and radiation therapy.39,13,25,42,43 Although the selected cohort of

patients who received radiation therapy alone had

less stage IV and node-positive patients, the contribution of chemotherapy to these larynx preservation

protocols remains undetermined. While previous

randomized prospective trials have not included a

radiation therapy-only arm, an ongoing prospective

randomized trial has included a radiation therapyonly arm, to address this question. This phase III trial

has 3 treatment arms including: (1) radiotherapy

alone, (2) sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy

and (3) concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Data from this study will help to further define the

optimal treatment for patients with advanced larynx

cancer. Additionally, 2 studies have recently been

published which compared radiotherapy alone to

concurrent chemotherapy (cisplatin/5-fluorouracil)

and radiotherapy in patients with locoregionallyadvanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and

neck.44,45 In these studies, between 36 and 56 percent

of patients had either laryngeal or hypopharyngeal

primaries. In both studies, a statistically significant

increase in 3-year relapse-free survival was seen in

the concurrent chemo/RT arm as compared to the

RT-alone arm (p < 0.00444 and p < 0.0345).

The debate also continues regarding the optimal

fractionation of radiation therapy, chemotherapeutic

agents, and optimal timing of chemotherapy and

radiation therapy (sequential vs. concomitant). Protocols with accelerated fractionation of radiotherapy

and plans using concomitant chemotherapy and

radiotherapy have been investigated. It has been postulated that part of the cause of increased locoregional failures seen with chemo/RT protocols result

from an accelerated tumor cell repopulation during

the prolonged course of treatment.46,47 Clinical and

experimental evidence suggest that tumor cell populations, after a lag period of several weeks, will

decrease their doubling time and increase their rate

of regrowth after the commencement of cytotoxic

treatment, regardless of whether it is chemotherapy

or radiation therapy.46,47 A longer treatment time will

therefore result in high rates of failure.48

In order to minimize these problems, investigators

have evaluated accelerated radiotherapy regimens and

concomitant chemo/RT protocols. In the past, accelerated (twice a day) courses of radiation therapy have

improved 3-year local control of advanced laryngeal

tumors (T3-4) from 26 to 59 percent (p < 0.0001).48,49

These gains in local control are not accomplished

without cost with regards to treatment related morbidity. In this study, although the larynx was anatomically preserved, its function was profoundly impaired

in a subset of patients, and significant long-term treatment related morbidity was seen in one-quarter of

patients. Additionally, all patients in this series undergoing salvage surgery after radiotherapy experienced

major wound complications.50 Ultimately a benefit in

local or regional control or survival was not seen,

although the power of this study was limited.

Another method of shortening treatment time,

decreasing the effects of accelerated tumor cell

repopulation and improving results involves the use

of concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Prior studies using concomitant chemotherapy and

radiation in advanced stage head and neck cancer

have shown promising results with regard to locoregional control, organ preservation and survival.51,52

Prospective randomized trials assessing the benefit

of concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy

as it applies to advanced stage laryngeal cancer,

however, are limited. As mentioned earlier, a randomized prospective trial comparing sequential to

concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy is

currently underway.

Additionally, randomized prospective studies

comparing sequential chemotherapy and radiation

therapy to concomitant chemo/RT in patients with

unresectable tumors of the head and neck have been

reported.27,53 While an improvement in locoregional

control was seen in the concomitant arm in the larger

study,53 neither study showed a difference in overall

survival.27,53 At this time, neither accelerated fraction

radiation therapy nor concomitant chemo/RT have

conclusively demonstrated a benefit in treating

advanced stage laryngeal cancer relative to induc-

The Larynx:Advanced Stage Disease

tion chemotherapy followed by conventional fraction radiation therapy. For this reason, along with the

potential for treatment related morbidity, it remains

investigational at this time.

Finally, novel treatment strategies continue to

evolve which intend to further improve the survival

and functional outcome in patients with advanced

cancer of the larynx. One such unique strategy utilizes the high-dose intra-arterial cisplatin with a systemic neutralizing agent along with conventional

radiation therapy.54 In this study, where the majority

of patients had stage IV disease (86%) and clinically

involved regional lymph nodes (79%), a major

response rate was seen in 95 percent of patients. Nine

of 10 patients retained their larynx and 2-year disease-specific survival was 76 percent. It should be

noted that 3 of the 42 patients experienced central

nervous system complications as a result of catheritization of the carotid system. Nevertheless, this

remains a promising option and a novel approach in

the treatment of advanced laryngeal cancer.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

CONCLUSION

The treatment of patients with advanced cancers of

the larynx has changed dramatically over the last 2

decades. While anatomic preservation of the larynx

can now be achieved in a large fraction of patients,

overall survival remains unchanged. The continued

optimization of multimodality treatment paradigms

along with the incorporation of biological markers,

novel treatment approaches, novel chemotherapeutic

agents and innovative biologic and gene transfer

techniques will hopefully further increase our ability

to improve survival in these patients.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

REFERENCES

17.

1. Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Funk GF, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124(9):95162.

2. Shah JP, Karnell LH, Hoffman HT, et al. Patterns of care for

cancer of the larynx in the United States. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123(5):47583.

3. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with

surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal

cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal

Cancer Study Group [see comments]. N Engl J Med

1991;324(24):168590.

4. Jacobs C, Goffinet DR, Goffinet L, et al. Chemotherapy as a

18.

19.

20.

21.

167

substitute for surgery in the treatment of advanced

resectable head and neck cancer. A report from the Northern California Oncology Group. Cancer 1987;60(6):

117883.

Demard F, Chauvel P, Santini J, et al. Response to

chemotherapy as justification for modification of the

therapeutic strategy for pharyngolaryngeal carcinomas.

Head Neck 1990;12(3):22531.

Pfister DG, Strong E, Harrison L, et al. Larynx preservation

with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy in

advanced but resectable head and neck cancer. J Clin

Oncol 1991;9(5):8509.

Karp DD, Vaughan CW, Carter R, et al. Larynx preservation

using induction chemotherapy plus radiation therapy as

an alternative to laryngectomy in advanced head and neck

cancer. A long-term follow-up report. Am J Clin Oncol

1991;14(4):2739.

Urba SG, Forastiere AA, Wolf GT, et al. Intensive induction

chemotherapy and radiation for organ preservation in

patients with advanced resectable head and neck carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1994;12(5):94653.

Clayman GL, Weber RS, Guillamondegui O, et al. Laryngeal

preservation for advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal

cancers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121(2):

21923.

Myers EN, Alvi A. Management of carcinoma of the supraglottic larynx: evolution, current concepts, and future

trends. Laryngoscope 1996;106(5 Pt 1):55967.

Nguyen TD, Malissard L, Theobald S, et al. Advanced carcinoma of the larynx: results of surgery and radiotherapy

without induction chemotherapy (19801985): a multivariate analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996;36(5):

10138.

Kirchner JA, Owen JR. Five hundred cancers of the larynx

and pyriform sinus. Results of treatment by radiation and

surgery. Laryngoscope 1977;87(8):1288303.

Harwood AR, Hawkins NV, Beale FA, et al. Management of

advanced glottic cancer. A 10-year review of the Toronto

experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1979;5(6):

899904.

Harwood AR, Rawlinson E. The quality of life of patients following treatment for laryngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys 1983;9(3):3358.

Dahm JD, Sessions DG, Paniello RC, Harvey J. Primary subglottic cancer. Laryngoscope 1998;108(5):7416.

Levendag P, Sessions R, Vikram B, et al. The problem of neck

relapse in early stage supraglottic larynx cancer. Cancer

1989;63(2):3458.

Meyer-Breiting E, Burkhardt A. Tumours of the larynx:

Histopathology and clinical inferences. New York (NY):

Springer-Verlag; 1988.

Oliver H. Beahrs OH. Manual for staging of cancer/ American Joint Commission on Cancer. Philadelphia (PA): JB

Lippincott Co; 1997.

Reidenbach MM. The paraglottic space and transglottic cancer:

anatomical considerations. Clin Anat 1996;9(4):24451.

Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, et al. Otolaryngologyhead & neck surgery: St. Louis (MO): MosbyYear Book, Inc.; 1998.

Som PM, Curtin HD. Head and neck imaging. St. Louis

(MO): Mosby-Year Book, Inc.; 1996.

168

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics,

1999 [see comments]. CA Cancer J Clin 1999;49(1):

831, 1.

Pfister D, Armstrong J, Strong E, et al. A matched pair analysis of cisplatin/5-fluorouracil versus other cisplatin based

regimens as induction chemotherapy for larynx preservation treatment. Proceedings of the American Society of

Clinical Oncology 1993;12:280.

Pfister D, Harrison L, Kraus D, et al. Larynx preservation:

does induction cisplatin based chemotherapy compromise

the delivery of concomitant chemotherapy with radiation

therapy. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical

Oncology 1994;13:292.

Shirinian MH, Weber RS, Lippman SM, et al. Laryngeal

preservation by induction chemotherapy plus radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: the M. D.

Anderson Cancer Center experience. Head Neck 1994;

16(1):3944.

Harrison LB, Raben A, Pfister DG, et al. A prospective phase

II trial of concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy with

delayed accelerated fractionation in unresectable tumors of

the head and neck. Head Neck 1998;20(6):497503.

Pinnaro P, Cercato MC, Giannarelli D, et al. A randomized

phase II study comparing sequential versus simultaneous

chemo-radiotherapy in patients with unresectable locally

advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Ann

Oncol 1994;5(6):5139.

Laccourreye H, Laccourreye O, Weinstein G, et al.

Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy: a partial

laryngeal procedure for selected supraglottic and transglottic carcinomas. Laryngoscope 1990;100(7):73541.

Laccourreye H, Menard M, Fabre A, et al. [Partial supracricoid

laryngectomy. Techniques, indications and results]. Ann

Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 1987;104(3):16373.

Laccourreye O, Salzer SJ, Brasnu D, et al. Glottic carcinoma

with a fixed true vocal cord: outcomes after neoadjuvant

chemotherapy and supracricoid partial laryngectomy with

cricohyoidoepiglottopexy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

1996;114(3):4006.

Pearson BW. Subtotal laryngectomy. Laryngoscope 1981;

91(11):190412.

Clark JR, Busse PM, Norris CM Jr, et al. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, and high-dose leucovorin

for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: longterm results. J Clin Oncol 1997;15(9):310010.

Soylu L, Kiroglu M, Aydogan B, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula following laryngectomy. Head Neck 1998;20(1):225.

Shemen LJ, Spiro RH. Complications following laryngectomy. Head Neck Surg 1986;8(3):18591.

Parikh SR, Irish JC, Curran AJ, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistulae in laryngectomy patients: the Toronto Hospital experience. J Otolaryngol 1998;27(3):13640.

Lazarus CL, Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, et al. Swallowing

disorders in head and neck cancer patients treated with

radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. Laryngoscope

1996;106(9 Pt 1):115766.

Terrell JE, Fisher SG, Wolf GT. Long-term quality of life

after treatment of laryngeal cancer. The Veterans Affairs

Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Arch Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 1998;124(9):96471.

Maas A. A model for quality of life after laryngectomy. Soc

Sci Med 1991;33(12):13737.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

DeSanto LW, Olsen KD, Perry WC, et al. Quality of life after

surgical treatment of cancer of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995;104(10 Pt 1):7639.

Singer MI. Blom ED. Tracheoesophageal puncture: A surgical prosthetic method for post laryngectomy speech

restoration. Third International Symposium on Plastic

Reconstructive Surgery of the Head and Neck, 1979.

Yuen A, Medina JE, Goepfert H, Fletcher G. Management of

stage T3 and T4 glottic carcinomas. Am J Surg 1984;

148(4):46772.

Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Stringer SP, et al. Stage T3

squamous cell carcinoma of the glottic larynx: a comparison of laryngectomy and irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys 1992;23(4):72532.

Harwood AR, Beale FA, Cummings BJ, et al. Supraglottic

laryngeal carcinoma: an analysis of dose-time-volume

factors in 410 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys

1983;9(3):3119.

Wendt TG, Grabenbauer GG, Rodel CM, et al. Simultaneous

radiochemotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in

advanced head and neck cancer: a randomized multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 1998;16(4):131824.

Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Lavertu P, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing concurrent chemotherapy and

radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in resectable stage

III and IV squamous cell head and neck cancer: preliminary results. Head Neck 1997;19(7):56775.

Withers HR, Taylor JM, Maciejewski B. The hazard of accelerated tumor clonogen repopulation during radiotherapy.

Acta Oncol 1988;27(2):13146.

Bourhis J, Wilson G, Wibault P, et al. Rapid tumor cell proliferation after induction chemotherapy in oropharyngeal

cancer. Laryngoscope 1994;104(4):46872.

Fowler JF, Lindstrom MJ. Loss of local control with prolongation in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys

1992;23(2):45767.

Wang CC, Blitzer PH, Suit HD. Twice-a-day radiation therapy for cancer of the head and neck. Cancer 1985;55(9

Suppl):21004.

Eisbruch A, Thornton AF, Urba S, et al. Chemotherapy followed by accelerated fractionated radiation for larynx

preservation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. J

Clin Oncol 1996;14(8):232230.

Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Van Kirk MA, et al. Continuous

course radiation therapy and concurrent combination

chemotherapy for squamous cell head and neck cancer.

Am J Clin Oncol 1994;17(5):36973.

Glicksman AS, Wanebo HJ, Slotman G, et al. Concurrent

platinum-based chemotherapy and hyperfractionated

radiotherapy with late intensification in advanced head

and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys

1997;39(3):7219.

Taylor SG, Murthy AK, Vannetzel JM, et al. Randomized

comparison of neoadjuvant cisplatin and fluorouracil

infusion followed by radiation versus concomitant treatment in advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol

1994;12(2):38595.

Robbins KT, Fontanesi J, Wong FS, et al. A novel organ

preservation protocol for advanced carcinoma of the larynx and pharynx. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

1996;122(8):8537.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Radiotherapy in Penile Carcinoma: Dr. Ayush GargDocument32 paginiRadiotherapy in Penile Carcinoma: Dr. Ayush GargMohammad Mahfujur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saints and Mahatmas of IndiaDocument290 paginiSaints and Mahatmas of IndiaRajeswari Ranganathan100% (2)

- TNM Classification 8th Edition 2017Document8 paginiTNM Classification 8th Edition 2017Mohammed Mustafa Shaat100% (1)

- Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Staging of Colorectal Cancer - UpToDate PDFDocument41 paginiClinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Staging of Colorectal Cancer - UpToDate PDFVali MocanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sant TukArAm English BiographyDocument16 paginiSant TukArAm English BiographyGanesh RahaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part II Color Oral Pathology Picture Booklet (2007-2008) PDFDocument14 paginiPart II Color Oral Pathology Picture Booklet (2007-2008) PDFaerowongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale - Life, Mission, and MartyrdomDocument62 paginiSant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale - Life, Mission, and MartyrdomAmandeep Singh AujlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TMP 2243-Instructions For Candidates-1462031165Document7 paginiTMP 2243-Instructions For Candidates-1462031165savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- VitaminDocument8 paginiVitamindrusmansaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Sources of CalciumDocument4 paginiFood Sources of CalciumsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fluorine NMRDocument35 paginiFluorine NMRDrHamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uch 015741Document2 paginiUch 015741savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TMP - 2243-Inst. Advt. No. 02 of 2016 - 12 Posts281220077Document51 paginiTMP - 2243-Inst. Advt. No. 02 of 2016 - 12 Posts281220077savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TheoreticalExamWithAnswers 2012 PDFDocument50 paginiTheoreticalExamWithAnswers 2012 PDFiugulescu laurentiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relevance To Public Health: 2.1 Background and Environmental Exposures To Boron in The United StatesDocument13 paginiRelevance To Public Health: 2.1 Background and Environmental Exposures To Boron in The United StatesKhayrunnisa BMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Mineral Calcium and Its Role in Bone HealthDocument14 paginiEssential Mineral Calcium and Its Role in Bone HealthHabsah Omar MasrunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ReadMe PDFDocument1 paginăReadMe PDFsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutfluoride PDFDocument12 paginiNutfluoride PDFsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dragon NaturallySpeaking 11Document71 paginiDragon NaturallySpeaking 11savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ppssastri Adiparva Part1Document1.005 paginiPpssastri Adiparva Part1savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nut FluorideDocument4 paginiNut FluoridesavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGM Dental Coll Navi Mumbai 130214Document2 paginiMGM Dental Coll Navi Mumbai 130214savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dragon Naturally Speaking 10Document1 paginăDragon Naturally Speaking 10Norazaliza LizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ReadMe PDFDocument1 paginăReadMe PDFsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fellowship Revision by Government of IndiaDocument3 paginiFellowship Revision by Government of Indiaatul_saraf001Încă nu există evaluări

- Prospectus Jan2017Document59 paginiProspectus Jan2017savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIIMS PG July 2016 ProspectusDocument56 paginiAIIMS PG July 2016 ProspectussavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- ApplicationForm PDFDocument1 paginăApplicationForm PDFsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

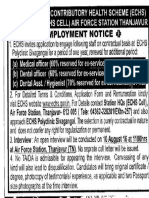

- Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (Echs) Jamnagar & Rajkot Employment NoticeDocument1 paginăEx-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (Echs) Jamnagar & Rajkot Employment NoticesavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adv PcscoimDocument1 paginăAdv PcscoimsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prospectus Jan2017Document59 paginiProspectus Jan2017savyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (Echs) Jamnagar & Rajkot Employment NoticeDocument1 paginăEx-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (Echs) Jamnagar & Rajkot Employment NoticesavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- JRADEDocument2 paginiJRADEsavyasachinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TesticularDocument79 paginiTesticularAndryanto リクア SutantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCLCDocument80 paginiSCLCraj patelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02.TNM 8 - 2017 PDFDocument26 pagini02.TNM 8 - 2017 PDFThiago TinôcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- IVMS Cell Biology and Pathology Flash Facts IDocument4.999 paginiIVMS Cell Biology and Pathology Flash Facts IMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.0% (2)

- CI-01 - Cancer (Kanser)Document2 paginiCI-01 - Cancer (Kanser)jijiqÎncă nu există evaluări

- 681 FullDocument6 pagini681 FullKurnia AnharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathology Outlines - StagingDocument1 paginăPathology Outlines - StagingHarshit ChoudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integumentary System: Anatomy, Functions, and Skin CancerDocument12 paginiIntegumentary System: Anatomy, Functions, and Skin CancerCaereel LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Axillary ClearenceDocument9 paginiAxillary ClearencelakanthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mid QuestionsDocument4 paginiMid QuestionsMAMA LALAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Satisfaction of Ruqyah On Cancer PatientsDocument5 paginiThe Satisfaction of Ruqyah On Cancer PatientsNinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification and Treatment of Bone TumorsDocument6 paginiClassification and Treatment of Bone TumorsRonald TejoprayitnoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anees Ahmed Corrected Thesis - RecentDocument135 paginiAnees Ahmed Corrected Thesis - RecentAbdul MunimÎncă nu există evaluări

- NEW AJCC/UICC STAGING SYSTEM FOR HPV-RELATED CANCERSDocument36 paginiNEW AJCC/UICC STAGING SYSTEM FOR HPV-RELATED CANCERSGalgalo GarbichaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rectal CancerDocument20 paginiRectal CancerSantosh BabuÎncă nu există evaluări

- WJRV 4 I 8Document59 paginiWJRV 4 I 8Wenny EudensiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esophageal Cancer - A Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Staging Workup and Treatment Modalities PDFDocument10 paginiEsophageal Cancer - A Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Staging Workup and Treatment Modalities PDFLUCIANAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protocol Update Dec 2019Document13 paginiProtocol Update Dec 2019Aarzu ChoudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children With Cancer PDFDocument92 paginiChildren With Cancer PDFThalani NarasiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Practice Guidelines: Biliary Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-UpDocument10 paginiClinical Practice Guidelines: Biliary Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-UpPutri MauraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinico-Radiological Co-Relation of Carcinoma Larynx and Hypopharynx: A Prospective StudyDocument7 paginiClinico-Radiological Co-Relation of Carcinoma Larynx and Hypopharynx: A Prospective StudyDede MarizalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iota AdnexDocument10 paginiIota Adnexlinh hoàngÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Horizons in The Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Review ArticleDocument11 paginiNew Horizons in The Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Review ArticleRucelia Michiko PiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Value of Pre-Operative Serum CA125 Level For Prediction of Prognosis in Patients With Endometrial CancerDocument7 paginiValue of Pre-Operative Serum CA125 Level For Prediction of Prognosis in Patients With Endometrial CancerFerdina NidyasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Au 2003Document7 paginiAu 2003Didi Nurhadi IllianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enneking Stadializare OS MSKDocument15 paginiEnneking Stadializare OS MSKVlad RakoczyÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCM 119 - Rle (Prelim) Week 1: Immune Response Immunity: Natural and Acquired Immunity - Ma'am VAB Immune ResponseDocument13 paginiNCM 119 - Rle (Prelim) Week 1: Immune Response Immunity: Natural and Acquired Immunity - Ma'am VAB Immune ResponseJamaica Leslie Noveno100% (1)