Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

45 People v. Mamaril Dabao

Încărcat de

Alexa0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări1 paginăSearch warrant is null and void and the search and seizure made at Mamaril's residence is illegal. Mamaril testified that he was at his parent's house that day because he and his live-in partner visited his mother. Under Art. III, Sec. 2 of the Constitution and Rule 126, Secs. 4 and 5 of the Rules of Court, the issuance of a search warrant is justified only upon a finding of probable cause.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentSearch warrant is null and void and the search and seizure made at Mamaril's residence is illegal. Mamaril testified that he was at his parent's house that day because he and his live-in partner visited his mother. Under Art. III, Sec. 2 of the Constitution and Rule 126, Secs. 4 and 5 of the Rules of Court, the issuance of a search warrant is justified only upon a finding of probable cause.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări1 pagină45 People v. Mamaril Dabao

Încărcat de

AlexaSearch warrant is null and void and the search and seizure made at Mamaril's residence is illegal. Mamaril testified that he was at his parent's house that day because he and his live-in partner visited his mother. Under Art. III, Sec. 2 of the Constitution and Rule 126, Secs. 4 and 5 of the Rules of Court, the issuance of a search warrant is justified only upon a finding of probable cause.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 1

DABAO, ALEXA

Article III. Section 2. Requisites of a valid warrant.

People v. Mamaril - 420 SCRA 662 [2004] (GR 147607)

FACTS:

SPO2 Chito Esmenda applied before the RTC of Lingayen for a search warrant authorizing the search for marijuana

at the family residence of accused Mamaril, and thereafter, it was subsequently issued. During the search operation,

the searching team confiscated sachets of suspected marijuana leaves. Police officers took pictures of the confiscated

items and prepared a receipt of the property seized and certified that the house was properly searched which was

signed by the Mamaril and the 2 barangay officials who witnessed the search.

After the search, the police officers brought Mamaril and the confiscated articles to the PNP station. After weighing

the specimens and testing the same, the PNP Crime Laboratory issued a report finding the specimens to be positive

for the presence of marijuana. Moreover, the person who conducted the examination on the urine sample of

Mamaril affirmed that he was positive for the same.

In his defense, Mamaril denied that he was residing at his parents house at Lingayen since he has been residing at a

rented house at Sta. Barbara and declared that it was his brother and the latters family who were residing with his

mother, but on said search operation, his brother and family were not in the house since they were at the fishpond.

He testified that he was at his parents house that day because he and his live-in partner visited his mother, that he

saw the Receipt of Property Seized for the first time while he was testifying in court and admitted that the signature

on the certification that the house was properly searched was his.

ISSUE:

W/N the search warrant is valid.

HELD: No. Search warrant is null and void and the search and seizure made at Mamarils residence is illegal.

Under Art. III, Sec. 2 of the Constitution and Rule 126, Secs. 4 & 5 of the Rules of Court, the issuance of a search

warrant is justified only upon a finding of probable cause. In determining the existence of probable cause, it is

required that: 1) the judge must examine the complaint and his witnesses personally; 2) the examination must be

under oath; 3) the examination must be reduced in writing in the form of searching questions and answers. In this

case, the records only show the existence of an application for a search warrant and the affidavits of the

complainants witnesses since the clerk of court could not produce the sworn statements of the complainant and his

witnesses showing that the judge examined them in the form of searching questions and answers. Thus, the

prosecution failed to prove that the judge who issued the warrant put into writing his examination of the applicant

and his witnesses in the form of searching questions and answers before issuance of the search warrant. Mere

affidavits of the complainant and his witnesses are not sufficient. Such written examination is necessary in order that

the judge may be able to properly determine the existence and non-existence of probable cause. Therefore, the SSC

holds that said search warrant is tainted with illegality by failure of the judge to conform with the essential requisites

of taking the examination in writing and attaching to the record, rendering the search warrant invalid.

Before his residence was searched, the police authorities presented a search warrant to Mamaril. However, at that

time they presented the warrant, Mamaril could not determine if it was issued in accordance with law. It was only

during the trial that Mamaril, through his counsel, had reason to believe that the search warrant was illegally issued.

The Court construes the silence of Mamaril when the police showed him the warrant as a demonstration of regard

for the supremacy of the law. Moreover, Mamaril seasonably objected on constitutional grounds to the admissibility

of the evidence seized pursuant to said warrant during the trial, after the prosecution formally offered its evidence.

Under the circumstances, no intent to waive his rights can reasonably be inferred from his conduct before or during

the trial.

No matter how incriminating the articles taken from the appellant may be, their seizure cannot validate an invalid

warrant since nothing can justify the issuance of the search warrant but the fulfillment of the legal requisites. The

requirement mandated by law that the examination of the complaint and his witnesses must be under oath and

reduced to writing in the form of searching questions and answers was not complied with, rendering the search

warrant invalid. Consequently, the evidence seized pursuant to illegal search warrant cannot be used in evidence

against Mamaril in accordance with Section 3 (2) Article III of the Constitution (Exclusionary Rule).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Csm6 Ext1y11 BookDocument955 paginiCsm6 Ext1y11 BookJesse Davis100% (12)

- AONo 2018-090Document4 paginiAONo 2018-090AlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 May 2020 The Return-To-Work Checklist: Focus On Labor: Item Comment A Working Arrangements With EmployeesDocument8 pagini20 May 2020 The Return-To-Work Checklist: Focus On Labor: Item Comment A Working Arrangements With EmployeesAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongDocument7 paginiPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongJoanna EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant Defendant-Appellant Cohn, Fisher & Dewitt William C. Brandy Gabriel La O Crossfield & O'BrienDocument5 paginiPlaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant Defendant-Appellant Cohn, Fisher & Dewitt William C. Brandy Gabriel La O Crossfield & O'BrienAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supplemental Guidelines On Workplace Prevention and Control of COVID-19 - Philippines - ICLG - Com Online UpdatesDocument3 paginiSupplemental Guidelines On Workplace Prevention and Control of COVID-19 - Philippines - ICLG - Com Online UpdatesAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conciliation-Mediation - National Conciliation and Mediation BoardDocument19 paginiConciliation-Mediation - National Conciliation and Mediation BoardAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents Solicitor General Brillantes Navarro Jumamil Arcilla Escolin & Martinez Law O CesDocument12 paginiPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents Solicitor General Brillantes Navarro Jumamil Arcilla Escolin & Martinez Law O CesAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perez Vs CADocument8 paginiPerez Vs CADenise Jane DuenasÎncă nu există evaluări

- OG July 16 2020-Omnibus-Guidelines-On-The-Implementation-Of-Community-Quarantine-In-The-PhilippinesDocument27 paginiOG July 16 2020-Omnibus-Guidelines-On-The-Implementation-Of-Community-Quarantine-In-The-PhilippinesdonhillourdesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1694 Amendments To The Procedural Rules With EnclosureDocument10 pagini1694 Amendments To The Procedural Rules With EnclosureAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nonprofit Law in The Philippines: International Center For Not-for-Profit Law Lily LiuDocument15 paginiNonprofit Law in The Philippines: International Center For Not-for-Profit Law Lily LiuAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DOH Interim Guidelines On The Return-to-Work (dm2020-0220)Document5 paginiDOH Interim Guidelines On The Return-to-Work (dm2020-0220)SamJadeGadianeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongDocument7 paginiPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongJoanna EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant Defendant-Appellant Cohn, Fisher & Dewitt William C. Brandy Gabriel La O Crossfield & O'BrienDocument5 paginiPlaintiff-Appellant Vs Vs Defendant Defendant-Appellant Cohn, Fisher & Dewitt William C. Brandy Gabriel La O Crossfield & O'BrienAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2UCLJLJ40 - Good Faith PDFDocument24 pagini2UCLJLJ40 - Good Faith PDFGalib YuhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nagoya ProtocolDocument15 paginiNagoya ProtocolgcanalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A.C. No. L-1117Document1 paginăA.C. No. L-1117AlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongDocument7 paginiPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Napoleon J. Poblador Pinito W. Mercado and Pablo S. BadongJoanna EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perez Vs CADocument8 paginiPerez Vs CADenise Jane DuenasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Pay Gap Article PDFDocument128 paginiGender Pay Gap Article PDFAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vda. de Aranas v. AranasDocument3 paginiVda. de Aranas v. AranasAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13-89032 Ebook From DM 9-9-2014Document151 pagini13-89032 Ebook From DM 9-9-2014AlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaid vs. PPLDocument8 paginiGaid vs. PPLclandestine2684Încă nu există evaluări

- Miciano v. BrimoDocument2 paginiMiciano v. BrimoAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lw27na3Dec04Competition (XV1135)Document52 paginiLw27na3Dec04Competition (XV1135)ngtthuylinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaid vs. PPLDocument8 paginiGaid vs. PPLclandestine2684Încă nu există evaluări

- Competition Law in VietnamDocument126 paginiCompetition Law in VietnamAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- International School v. CADocument2 paginiInternational School v. CAAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 23 - Cebu Shipyard v. William LinesDocument2 pagini23 - Cebu Shipyard v. William LinesAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gashem v. CADocument3 paginiGashem v. CAAlexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Welcome To The Jfrog Artifactory User Guide!Document3 paginiWelcome To The Jfrog Artifactory User Guide!RaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ang Tibay Vs CADocument2 paginiAng Tibay Vs CAEarl LarroderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aìgas of Bhakti. at The End of The Last Chapter Uddhava Inquired AboutDocument28 paginiAìgas of Bhakti. at The End of The Last Chapter Uddhava Inquired AboutDāmodar DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Context: Lesson Author Date of DemonstrationDocument4 paginiContext: Lesson Author Date of DemonstrationAR ManÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donor S Tax Exam AnswersDocument6 paginiDonor S Tax Exam AnswersAngela Miles DizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 115 FinargDocument294 pagini115 FinargMelvin GrijalbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tool For The Assessment of Project Com PDFDocument9 paginiA Tool For The Assessment of Project Com PDFgskodikara2000Încă nu există evaluări

- Danculos - M1 - L3 - Activity TasksDocument2 paginiDanculos - M1 - L3 - Activity TasksAUDREY DANCULOSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading İzmir Culture Park Through Women S Experiences Matinee Practices in The 1970s Casino SpacesDocument222 paginiReading İzmir Culture Park Through Women S Experiences Matinee Practices in The 1970s Casino SpacesAta SagirogluÎncă nu există evaluări

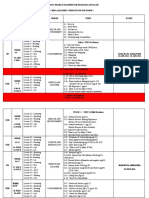

- RPT Form 2 2023Document7 paginiRPT Form 2 2023NOREEN BINTI DOASA KPM-GuruÎncă nu există evaluări

- MISKDocument134 paginiMISKmusyokaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9.2 Volumetric Analysis PDFDocument24 pagini9.2 Volumetric Analysis PDFJoaquinÎncă nu există evaluări

- AS 1 Pretest TOS S.Y. 2018-2019Document2 paginiAS 1 Pretest TOS S.Y. 2018-2019Whilmark Tican MucaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amtek Auto Analysis AnuragDocument4 paginiAmtek Auto Analysis AnuraganuragÎncă nu există evaluări

- Broshure JepanDocument6 paginiBroshure JepanIrwan Mohd YusofÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brochure 8 VT 8Document24 paginiBrochure 8 VT 8David GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bubble ColumnDocument34 paginiBubble ColumnihsanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bossa Nova Book PDFDocument5 paginiBossa Nova Book PDFschmimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All ChapterDocument67 paginiPractice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All Chaptereric.temple792100% (3)

- 7 - LESSON PLAN CULTURAL HERITAGE AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY - Lesson PlanDocument4 pagini7 - LESSON PLAN CULTURAL HERITAGE AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY - Lesson PlanRute SobralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Download Social Animal 14th Edition Aronson Test BankDocument35 paginiFull Download Social Animal 14th Edition Aronson Test Banknaeensiyev100% (32)

- Tugas, MO - REVIEW JURNAL JIT - Ikomang Aditya Prawira Nugraha (1902612010304)Document12 paginiTugas, MO - REVIEW JURNAL JIT - Ikomang Aditya Prawira Nugraha (1902612010304)MamanxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spouses Aggabao V. Parulan, Jr. and Parulan G.R. No. 165803, (September 1, 2010) Doctrine (S)Document9 paginiSpouses Aggabao V. Parulan, Jr. and Parulan G.R. No. 165803, (September 1, 2010) Doctrine (S)RJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oracle QuestDocument521 paginiOracle Questprasanna ghareÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Paper-2) 20th Century Indian Writing: Saadat Hasan Manto: Toba Tek SinghDocument18 pagini(Paper-2) 20th Century Indian Writing: Saadat Hasan Manto: Toba Tek SinghApexa Kerai67% (3)

- A Study of The Concept of Future-Proofing in Healtcare Building Asset Menagement and The Role of BIM in Its DeliveryDocument285 paginiA Study of The Concept of Future-Proofing in Healtcare Building Asset Menagement and The Role of BIM in Its DeliveryFausto FaviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- J of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2019 - Zhang - A Cream of Herbal Mixture To Improve MelasmaDocument8 paginiJ of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2019 - Zhang - A Cream of Herbal Mixture To Improve Melasmaemily emiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 50 p7 Kids AvikdeDocument2 pagini50 p7 Kids AvikdebankansÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Machine StopsDocument14 paginiThe Machine StopsMICHAEL HARRIS USITAÎncă nu există evaluări