Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Withdrawal Assessment

Încărcat de

George SiegDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Withdrawal Assessment

Încărcat de

George SiegDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Visionary Leadership for Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurses Around the World

I N T E R N A T I O N A L S O C I E T Y O F P S Y C H I A T R I C- ME N T A L H E A L T H N U R S E S

Position Paper, October 2000

Assessment and Identification Management of

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS) in the Acute Care Setting

Background

Alcoholism is a chronic, neurobiological disorder that leads to a variety of healthcare problems often

leading to acute care hospitalization. It is not surprising that alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), is a

common occurrence in acute care patients. AWS is a potentially life threatening condition, often coupled

with co-morbidities that can adversely affect the outcome of treatment. The focus of this position paper is

to address the acute care patient who is at risk for or has developed AWS. Therefore, the

recommendations are directed to the patient with alcohol withdrawal. However, many acute care patients

are suffering from polysubstance abuse and a strong denial system (patient and family) which often

produces either a complex or unexpected withdrawal syndrome presentation. Those patients require

immediate referral to addiction or psychiatric nurse/physician specialists in the medical center due to the

complex nature of their addiction and possible withdrawal state. The goals of this ISPN position

statement are to: promote nursing and medical care that is evidence-based, promote an environment that

addresses early identification and aggressive treatment of AWS that is effective and safe, and decrease the

use of automatic chemical or mechanical restraints in the treatment of patients with AWS.

Impact of Substance Abuse on Global and National Health

Alcoholism and alcohol abuse produce significant threats to health worldwide. It has been ranked as the

fourth leading cause of disability and healthcare burden in a global report (Murray & Lopez, 1996). In the

United States, alcoholism has a high lifetime prevalence rate of ten percent. (NIDA & NIAAA, 1998). At

least 15.4 million adults have alcohol-related problems (Miller, Gold, & Smith, 1997). Alcohol-related

costs adversely impact on the United States healthcare system and society at large. This healthcare

problem impacts on patients and affects many individuals while creating enormous social, physical, and

psychological problems. The Ninth Special Report to Congress indicates increasing costs, estimated at

$166.5 billion per year in direct and indirect healthcare and social costs (Ninth Report, 1997).

Alcohol has been identified as a factor in fifty percent of all motor vehicle crashes, burns, interpersonal

violence including homicides and increased crime (Rivara et al., 1993; NIAAA 1998; Ninth Special

Report, 1997). More years are lost to alcohol-related causes than to heart disease; a rate that is second

only to cancer (Miller, Gold, & Smith, 1997). Alcohol abuse is a serious problem for elderly adults

affecting as many as 17% (Blow, 1998;Caracci & Miller, 1991). Until recently, problem drinking in the

elderly has been ignored and minimized by both healthcare professionals and the general public. The

treatment of persons with coexisting mental and substance abuse disorders is a subject of growing

importance, which may involve 40 to 50% of the persons with a psychiatric diagnosis (Miller, Gold, &

Smith, 1997).

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 2

Healthcare providers encounter patients with alcohol related problems in all healthcare settings; however,

the patients' alcohol abuse is often not recognized, diagnosed or treated. Society's ambivalent views about

alcohol and other drug use may be reflected in the attitudes of many healthcare providers, including

nurses, who fail to accurately identify substance abuse problems, or harshly judge those patients (CASA,

2000). Nurses are in key positions to identify alcohol problems in patients and to facilitate their

access to appropriate and effective treatment. When substance abuse testing and assessment, especially

alcohol related, become routine, acute care settings can expect: improved patient management and followup, increased patient and family satisfaction and improved nursing morale. (Rostenberg, 1995).

Symptoms of Acute Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Alcohol withdrawal in the acute care patient is complex, underdiagnosed, and often under or mistreated

by utilizing monopharmacotherapy. Alcohol withdrawal can begin from 6 to 24 hours following cessation

of drinking or if a significant reduction in the usual alcohol consumption occurs (Giannis, 2000: Myrick

& Anton, 2000). Alcohol withdrawal delirium is typically experienced by the third day, and up to the

fifth day of abstinence. DePetrillo and McDonough (1999a) identify three symptom clusters that differ

physiologically, and the preferred treatment agents for each cluster. The three clusters provide a model

for pharmacologic intervention based on symptom presentation. Refer to Appendix 1Summary of Signs

and Symptoms by AWS Type.

Most patients develop sensory hypersensitivity. Alcohol-related seizures are often associated with head

trauma(s), history of seizures, and electrolyte instability (untreated hypomagnesaemia, hypokalemia,

hyponatremia, and hypoglycemia. Electrolyte instability can produce a medical/psychiatric emergency.

Symptoms are generally more severe and complex with women, older age, poor general health, poor

nutritional status, amounts of alcohol consumed regularly, and a long duration of alcohol dependency

(DePetrillo et al., 1999b; Sache, 2000). It is essential and medically appropriate to screen, assess, and

identify patients with alcohol-related problems so that the necessary and appropriate medical and nursing

care is instituted in a timely manner. Refer to Appendix 1 Summary of Signs and Symptoms by AWS

Type.

Pharmacologic Management of AWS

ISPN believes that the major goal of pharmacologic treatment for AWS is to decrease mortality and

morbidity,since AWS can be life threatening. It is acknowledged that alcohol withdrawal severity varies

significantly, and the medications and amounts needed to effectively manage symptoms also vary

significantly from patient to patient and among patient-related episodes of AWS. Refer to Appendix 1

Summary of Signs and Symptoms by AWS Type for symptom focused pharmacologic interventions.

Management of Medical and Psychiatric Illness

Chronic alcohol consumption is associated with a number of medical complications that must be

addressed during the acute care stay. Also, chronic alcohol consumption may exacerbate pre-existing

psychiatric-mental health illnesses. The behavioral, depletion of neurotransmitters and social problems

associated with chronic alcohol consumption may lead to the secondary development of a psychiatric

illness, such as anxiety and/or depression and an increased rate of suicide. Alcohol related complications

are described in Appendix 2: Medical Conditions Related to Alcohol Abuse.

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 3

Recommendations

The quality and efficacy and outcomes of acute care services and treatment are

inhibited and compromised if patients' alcohol patterns and histories are not

known to the healthcare team planning and providing acute care services.

Therefore ISPN recommends that the following measures be instituted:

All healthcare providers should become knowledgeable about AWS symptom identification,

utilization of routine screening methods, AWS assessment/quantification tools, specific

pharmacologic intervention, and identification and utilization of acute care resources to facilitate

successful referral to the appropriate level of addiction treatment.

All healthcare providers should conduct routine screening for substance use in their practice and

identify patients at risk for abuse and dependency.

All nurses function as advocates to insure their patients receive appropriate screening and expedient

treatment for AWS in conjunction with appropriate referrals to maintain the patients functional and

cognitive status.

Screening for Alcohol Abuse or Dependence

All patients should be screened by their healthcare providers at the point of entry into the healthcare

system. They should be asked about alcohol use, and the presence of any alcohol-related problems.

All acute care patients should be screened using reliable and easy to use screening tool that can be

implemented in any acute and emergency care environment. The CAGE questionnaire, with its four

questions, is an example of such a tool (Ewing, 1984; Beresford, 1990)), refer to Appendix 3 for

information on the CAGE questionnaire.

All acute care patients who are at high risk, (particularly trauma patients), or any patient who scores

two positive answers on the CAGE screening tool should have blood alcohol concentration (BAC)

determinations as well as urine toxicology screens performed on admission.

Assessment and Quantification of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS)

All acute care patients with either a positive CAGE or BAC should be assessed for the possibility of

developing Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS).

Assessment should be done using an evidence-based clinically focused assessment tool such as the

AWS Type Indicator (DePetrillo & McDonough, 1999).

All patients with any of the following: positive blood alcohol concentrations (BAC), positive urine

toxicology screens, and positive CAGE scores- receive further assessment for proper diagnosis and

prompt intervention for substance abuse/dependency. Consultation and referral to psychiatric

consultaition liaison nurse, addiction consultation nurse or other experts available within healthcare

system for evaluation will aid in diagnosis of coexisting (co morbid) psychiatric disorders.

Pharmacologic Management of AWS

The determination of medication and dosage administered is based on the identification and

quantification of AWS symptomatology demonstrated on the AWS Type Indicator or other objective

quantification tool.

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 4

Specific treatment is instituted immediately following patient assessment with an objective

quantification tool. Particular attention should be focused on managing signs and symptoms related

to increasing circulating levels of epinephrine, since the conditions related to hyperadrenergic state

are most commonly associated with AWS mortality and morbidity.

Treatment of patients with AWS should be based on individualized and dynamic

psychopharmacologic interventions, so patients receive the appropriate medications in the correct

dosages and combinations to effectively treat their AWS symptomatology.

Individualized and dynamic treatment requires that each symptom cluster is assessed and quantified,

and then treatment is instituted with the appropriate medication for each symptom cluster where there

are symptoms present.

ISPN does not support fixed dosing medication regimens: a fixed, standardized dose for all patients

cannot effectively or adequately treat AWS. (Mayo-Smith, 1997).

ISPN does not support PRN dosing without any mean of quantifying symptoms; it is an equally

inadequate method of detoxification (Mayo-Smith, 1997).

ISPN does not recommend or support the use of ethyl alcohol (oral or intravenous) in the treatment of

AWS because of the lack of controlled studies regarding its effectiveness (evidence is only anecdotal

reports and case studies). Additionally, there is well-documented evidence of adverse effects of ethyl

alcohol as a pharmacologic agent (Mayo-Smith, 1997).

ISPN does not recommend the use of automatic restraints (chemical or mechanical) for agitated

behavior due to AWS without first attempting environmental manipulation, calming techniques and

pharmacotherapy. (ISPN Position Statement, 2000)

Management of Medical and Psychiatric Illness

Alcohol associated medical and psychiatric problems must be identified, and treated appropriately

and concurrently.

The patient must be taught to understand the link between chronic alcohol consumption and the

medical illnesses or complications present including effects on psychosocialial functioning (job loss,

DUI, interpersonal violence-especially domestic violence, impact on children- one in four children

are raised in families where alcoholism or alcohol abuse is present).

The patient must be advised to seek treatment for alcohol dependence as a necessary strategy in the

treatment of any medical illnesses or complications present that can be linked to alcohol consumption.

Healthcare providers, especially nurses in acute care settings, should request consultation with

psychiatric/addiction colleagues to determine the presence of any coexisting psychiatric illness and

the appropriate treatment. (The identification of psychiatric symptomatology may not be clearly

established if the patient develops alcohol withdrawal delirium, but can be detected after the delirium

has resolved or through collateral interviews).

Healthcare providers need to consider additional consultations to enhance the patient's general well

being, functional status and cognitive functioning in conjunction with AWS treatment. Examples of

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 5

additional consultations are nutritional, physical therapy and occupational therapy. It is important to

identify any deficits that may interfere with further addiction treatment

Referral for Addiction Focused Treatment

All acute care patients who have been treated for AWS need a focused addiction and readiness to

change assessment (Prochaska et al., 1992) to assist patients, family and treatment providers in

determining the level and focus of addiction and possible psychiatric treatment. Acute care alcohol

detoxification only is incomplete and ineffective treatment for alcohol dependence.

Recovery focused treatment should also be individualized and may include community based mutual

help groups, low intensity outpatient treatment programs, high intensity outpatient treatment

programs, family or relationship therapy, individual therapy with a cognitive/behavioral focus, and/or

residential treatment.

All patients should be offered and receive an individualized referral for addiction treatment and all

options available to the patient should be discussed completely with the patient prior to their acute

care discharge.

Family members (including children), or significant others should be provided with community based

referrals to address the impact of alcoholism on them.

Summary

The early identification and clinically focused assessment of AWS in conjunction with individualized and

dynamic treatment results in increased patient comfort, decreased cost, decreased adverse consequences

related to the detoxification process, decreased percentage of patients leaving against medical advice

(AMA) and decreased the restraint incidences and length of time spent in restraints. Patient, family and

nursing satisfaction and with safety are all positively impacted with this approach to a potentially life

threatening syndrome.

Developed for ISPN by the ISPCLN AWS Task Force: Lynette Jack PhD. RN (Chairperson); Peggy Dulaney MSN,

RN , CS (Division Director-ISPCLN); Lenore Kurlowicz Ph,D, RN, CS; Susan Krupnick MSN, RN, CARN, CS; Susan

McCabe EdD, RN, CS; Leslie Nield-Anderson PhD, RN, Karen Ragaisis, MSN, APRN, CARN, CS. Reviewed by

Diane Snow, PhD, RN, CARN, CS, President, International Nurses Society on Addictions and Dr. Paolo DePetrillo

ISPN 2000

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 6

References

Beresford, T.P., Blow, K.C., Hill, e., et al. (1990). Clinical Practice: Comparison of CAGE questionnaire and computer

assisted laboratory profiles in screening for covert alcoholism. Lancet. 336, 482-485.

Blow, F. (1998). Substance abuse among older adults. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Treatment Improvement Protocol #26.

Caracci, G. & Miller, N. (1991). Epidemiology and diagnosis of alcoholism in the elderly-a review. International

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 6, 511-515.

CASA (2000). Missed Opportunity: National Survey of Primary Care Physicians and Patients on Substance Abuse.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Columbia University, New York, NY.

DePetrillo, P. & McDonough, M. (1999a). Alcohol withdrawal treatment manual. Glen Echo, MD: Focused Treatment

Systems.

DePetrillo, P., White, K.V., Ming, L., Hommer, D., & Goldman, D. (199b). Effects of Alcohol Use and Gender on the

Dynamics of EKG Time-Series Data. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 23,4(745-750.

Ewing, J. (1984). Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association, 252,

1905-1907.

Giannis A. (2000). An approach to drug abuse, intoxication, and withdrawal. American Family Physician. American

Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp.org, 5/1/00).

International Society of Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurses (2000). A Position Statement: On the Use of Restraint and

Seclusion. Philadelphia, PA: ISPN.

Mayo-Smith, M. (1997). Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal: A Meta-Analysis and Evidence Based

Practice Guideline. Journal of the American Medical Association. 278(2), 144-151.

Miller, N., Gold, M., & Smith, D. (1997). Manual of Therapeutics for Addictions. New York: Wiley-Liss.

Murray, J.L., & Lopez, A.D. (1996). The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and

Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Harvard School Public Health,

Harvard Press: Cambridge, MA .

Myrick, H. & Anton, R.F. (2000). Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal. CNS Spectrums. 5(2), 22-32.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). (1998).

The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States, 1992. Bethesdea, MD: National Institutes of

Health.

Ninth Report to the U.S.Congress on alcohol and health. (1997). Chapter 1: Epidemiology of alcohol use and alcoholrelated consequences. Washington,D.C.: Public Health Services.

Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C.,& Norcross, J.C. (1992). In search of how people change: applications to

addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 47(9), 1102-1114.

Rivara, F.P., Jurkovich, G.J., Gurney, J.G., Seguin, D., et al. (1993). The magnitude of acute and chronic alcohol

abuse in trauma patients. Archives of Surgery. 128:907-913.

Rostenberg, P. (1995). Alcohol and other drug screening of hospitalized trauma patients. Rockville, MD: Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Treatment Improvement

Protocol #16.

Sache, D. (2000). Delirium Tremens. American Journal of Nursing, 100, (5), 41-42.

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 7

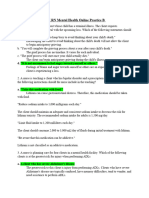

Appendix 1: Summary of Signs and Symptoms By The AWS Type

AWS TYPE

TYPE A

(CNS Excitation)

Physiologic Basis for

Symptom Manifestation

Deficiency in GABA

activity, with effect on

serotonin,

norepinephrine and

dopamine along with an

overactivity of certain

subtypes of NMDA

receptors.

Uneasiness, sense of

foreboding,

apprehension, motor

hyperactivity, enhanced

sensitivity and reaction

to abrupt sensory

stimuli, mood lability,

dysphoria, anxiety,

insomnia

Benzodiazepines

(lorazepam-Ativan,

diazepam-Valium,

chlordiazepoxideLibrium)

Signs and Symptoms

Recommended

Pharmacotherapy

(listed based on level of

effectiveness- highly

effective to some effect)

Carbamazepine

(Tegretol)

Valproic Acid

(Depakote)

TYPE B

(Adrenergic

Hyperactivity)

TYPE C

(AWS Delirium)

Increase in CNS

epinephrine and an

increase in circulating

levels of epinephrine

Postulated that the

glutamate-related

NMDA receptor

hypersensitivity plays a

role in AWS delirium

Chills, diaphoresis,

fever, hypermetabolic

state, hypertension,

muscle tremors,

mydriasis, nausea and

vomiting, palpitations,

piloerection, tachycardia

Attentional deficit,

disorientation, hyperalertness, impairment of

short-term memory,

impaired reasoning,

psychomotor agitation,

visual and auditory,

tactile hallucinations

Clonidine (Catapres)

Neuroleptics

(haloperidol-Haldol,

risperidone-Risperdal,

fluphenazine, Stelazine,

droperidol-Inapsine)

Beta Blockers

(propranolol-Inderal,

atenolol-Tenormin,

labetalol, Normodyne)

Valproic Acid

(Depakote)

Carbamazepine

(Tegretol)

Clonidine (Catapres)

Benzodiazepines

Adapted and used with permission from DePetrillo, P. & McDonough, M. (1999). Alcohol Withdrawal Treatment

Manual. Glen Echo, MD: Focused Treatment Systems.

Resource: For additional information and discussions with an addictionologist studying AWS use

http://www.sagetalk.com

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 8

Appendix 2: Medical Conditions Related to Alcohol Abuse

Cardiovascular

alcoholic cardiomyopathy

increased systolic and pulse pressure

tissue damage, weakened heart muscle, and heart failure

Gastrointestinal

abdominal distention, pain, belching, and hematemesis

acute and chronic pancreatitis

alcoholic hepatitis leading to cirrhosis

cancer of the esophagus, liver, or pancreas

esophageal varicies, hemorrhoids, and ascites

gastritis, colitis, and enteritis

gastric or duodenal ulcers

gastrointestinal malabsorption

hepatorenal syndrome

swollen, enlarged fatty liver

Genitourinary

hypogonadism, hypoandrogenization, hyperestrogenization in men

increased urinary excretion of potassium and magnesium (results in hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia)

infertility, decreased menstruation

prostate gland enlargement, leading to prostatitis and interference

with urination

prostate cancer

sexual dysfunction: decreased libido, sexual performance decreased,

impotency

Metabolic

hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia

ketoacidosis

osteoporosis

Hematologic

abnormal red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

anemia and increased risk of infection

bleeding tendencies, increased bruising, and decreased clotting time

mineral and vitamin deficiencies (folate, iron, phosphate, thiamine)

Neurologic

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, Marchiafava-Bignami disease, cerebellar degeneration

peripheral neuropathy, polyneuropathy

seizures

sleep disturbances

stroke (increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke)

Respiratory

cancer of the oropharynx

impaired diffusion, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, infection, and tuberculosis

respiratory depression causing decreased respiratory rate and cough reflex and increased susceptibility to

infection and trauma

Trauma related

burns, smoke inhalation injuries

injuries from motor vehicle crashes and falls

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

ISPN Position Paper, October 2000: AWS in the Acute Care Setting, p. 9

Appendix 3: Cage Questionnaire

The CAGE is a very brief questionnaire for detection of alcoholism. Item responses on the CAGE are

score 0 for NO and 1 for YES, with a higher score an indication of alcohol problems. A total score of 2

or more is considered clinically significant and requires a more focused and detailed assessment. The

following are the four questions that comprise the CAGE questionnaire.

1. Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

YES

NO

2. Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

YES

NO

3. Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?

YES

NO

4. Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to

YES

NO

steady your nerves to get rid of a hangover? (Eyeopener)

Source: Ewing, J.A. (1984). Detecting Alcoholism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 252, 1905-1907.

Additional Readings:

Burge, S. & Schneider, F. (1999). Alcohol-related problems: Recognition and Intervention. American Family

Physician. American Academy of Family Physicians Home Page (www.aafp.org, 1/15/99).

Davis, M. (2000). Alcohol and Drug Addiction. Medical Library (www.medical-library.org, 9/30/00).

Wesson, D. (1995). Detoxification from Alcohol and Other Drugs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Treatment Improvement Protocol # 19.

Additional Resources:

National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information, P.O. Box 2345, Rockville, MD 20847-2345,1-800-729-6686

National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, Inc., 12 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010,

1-800-NCA-CALL

800.826.2950

ISPN 1211 Locust St. Philadelphia PA 19107

215.545.8107 (f)

ispn@rmpinc.com (e)

www.ispn-psych .org

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Rejectingreality WestworldDocument9 paginiRejectingreality WestworldGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Redactiesecretaris, 10 TutersDocument8 paginiRedactiesecretaris, 10 TutersGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- litWinesEucharist Updated112711Document5 paginilitWinesEucharist Updated112711George SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10.1515 - Apeiron 2015 0054Document20 pagini10.1515 - Apeiron 2015 0054George SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Griffin Heroic DoublingDocument14 paginiGriffin Heroic DoublingGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tribal Philosophical Thoughts of The Higaunon of Iligan City, PhilippinesDocument8 paginiThe Tribal Philosophical Thoughts of The Higaunon of Iligan City, PhilippinesGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cebu A Not Rad HealingDocument9 paginiCebu A Not Rad HealingGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly: To Cite This Article: Betty Garcia PHD (2005) : Chapter 6: Incarcerated Latinas andDocument22 paginiAlcoholism Treatment Quarterly: To Cite This Article: Betty Garcia PHD (2005) : Chapter 6: Incarcerated Latinas andGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fasc Article p259 - 8Document3 paginiFasc Article p259 - 8George SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faith Healing in The Philippines Zeus SalazarDocument15 paginiFaith Healing in The Philippines Zeus SalazarGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- State of Hate 2020 Final PDFDocument140 paginiState of Hate 2020 Final PDFGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foucault Technologies Self Vermont PDFDocument15 paginiFoucault Technologies Self Vermont PDFGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boorse-A Second Rebuttal On HealthDocument42 paginiBoorse-A Second Rebuttal On HealthGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jinha Arif 2010 Article 50 MillionDocument10 paginiJinha Arif 2010 Article 50 MillionGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiological Responses in Sons of Alcoholics: Peter R. Finn, PH.D., and Alicia JustusDocument5 paginiPhysiological Responses in Sons of Alcoholics: Peter R. Finn, PH.D., and Alicia JustusGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- 63A799 GlobepatternDocument5 pagini63A799 GlobepatternnightclownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Roots of Italian WitchcraftDocument4 paginiAncient Roots of Italian WitchcraftWald PereiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15c Mens Italian GarmentsDocument12 pagini15c Mens Italian GarmentsGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk in Sons of AlcoholicsDocument5 paginiRisk in Sons of AlcoholicsGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tambiah, S Magic Science Religion and The Scope of RationalityDocument100 paginiTambiah, S Magic Science Religion and The Scope of Rationalityidunnolol100% (1)

- Alcohol Use InventoryDocument5 paginiAlcohol Use InventoryGeorge SiegÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oto Anorha 33 Free FileDocument86 paginiOto Anorha 33 Free FileGeorge Sieg100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Pastoral CycleDocument8 paginiPastoral CycleWesley Angelo CalayagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based GuideDocument44 paginiPrinciples of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based GuideKrishna RathodÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is AlcoholismDocument5 paginiWhat Is AlcoholismSapna KapoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shrishuddhinashamuktikendrabhopal Business SiteDocument20 paginiShrishuddhinashamuktikendrabhopal Business SiteComputer TricksÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Guidance Program - FinalDocument4 paginiSchool Guidance Program - FinalLoreto C. Morales82% (11)

- Rapport PortugalDocument157 paginiRapport PortugalLudovic ClerimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efraim Diveroli: 1-10-11 Sealed Sentencing Hearing DiveroliDocument15 paginiEfraim Diveroli: 1-10-11 Sealed Sentencing Hearing DiveroliInvestigative JournalistÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSYCH 505 Case Study Core FunctionsDocument8 paginiPSYCH 505 Case Study Core FunctionsHugsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Justice Society V Dangerous Drugs Board GR 157870 PDFDocument22 paginiSocial Justice Society V Dangerous Drugs Board GR 157870 PDFTheodore BallesterosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original PDF Orientation To The Counseling Profession 3rd Edition PDFDocument41 paginiOriginal PDF Orientation To The Counseling Profession 3rd Edition PDFkatharine.boyd46995% (38)

- June 2019 ExaminationDocument8 paginiJune 2019 ExaminationSmangele ShabalalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ATI RN Mental Health Online Practice BDocument38 paginiATI RN Mental Health Online Practice Bseansdrew2Încă nu există evaluări

- The Deadly Genius of Drug Cartels - Rodrigo CanalesDocument30 paginiThe Deadly Genius of Drug Cartels - Rodrigo CanalesBANJO BALANAÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3rd WK JULYDocument5 pagini3rd WK JULYMALOU ELEVERAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drugs and Alcohol in TeenagersDocument3 paginiDrugs and Alcohol in TeenagersDavid UrestiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addiction AssignmentDocument4 paginiAddiction AssignmentUmm ZainabÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of The CordillerasDocument6 paginiUniversity of The CordillerasGesler Pilvan SainÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 9165 Section 40-65Document52 paginiRA 9165 Section 40-65Lady Ann M. LegaspiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 Food Addiction Treatment Background PW FINAL 10-19-14Document90 pagini01 Food Addiction Treatment Background PW FINAL 10-19-14mariaaga100% (4)

- Pendekatan Kaunseling Dalam Rawatan & Pemulihan Penagihan DadahDocument23 paginiPendekatan Kaunseling Dalam Rawatan & Pemulihan Penagihan Dadahadib emirÎncă nu există evaluări

- SkyPointe Project PP - SwsDocument42 paginiSkyPointe Project PP - SwsPatricia MielcarekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise Addiction A Literature ReviewDocument7 paginiExercise Addiction A Literature Reviewc5sq1b48100% (1)

- RA 9165 Comprehensive Dangerous Drug BoardDocument46 paginiRA 9165 Comprehensive Dangerous Drug BoardLary BagsÎncă nu există evaluări

- WatDocument75 paginiWatPauloSchulteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Argument EssayDocument7 paginiArgument Essayapi-317136815Încă nu există evaluări

- Badac Activity Report 2022Document23 paginiBadac Activity Report 2022Blgu LucogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug Court Services For Female Offenders, 1996-1999 Evaluation of The Brooklyn Treatment CourtDocument55 paginiDrug Court Services For Female Offenders, 1996-1999 Evaluation of The Brooklyn Treatment CourtFrancisco EstradaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antipolo City Masa MasidDocument20 paginiAntipolo City Masa MasidMurphy Red100% (1)

- AxidityDocument13 paginiAxiditypokeman693Încă nu există evaluări

- 60 Group Therapy ActivitiesDocument9 pagini60 Group Therapy ActivitiesNavarro CaroÎncă nu există evaluări