Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Comparison of Affirm VPIII and Papanicolaou Tests

Încărcat de

Anonymous owTPhxMKDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Comparison of Affirm VPIII and Papanicolaou Tests

Încărcat de

Anonymous owTPhxMKDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Anatomic Pathology / Molecular Testing of Infectious Vaginitis

Comparison of Affirm VPIII and Papanicolaou Tests

in the Detection of Infectious Vaginitis

Angelique W. Levi, MD, Malini Harigopal, MD, Pei Hui, MD, PhD, Kevin Schofield, CT(ASCP),

and David C. Chhieng, MD, MBA, MSHI, MA (Hon)

Key Words: Molecular diagnostics; Cytopathology; Infectious disease; Candida species; Trichomonas vaginalis; Gardnerella vaginalis

CME/SAM

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

Upon completion of this activity you will be able to:

describe the Affirm VPIII test for infectious vaginitis.

list the preanalytic requirements for optimal performance of Affirm

VPIII testing for infectious vaginitis.

summarize the microbiology and pathology of infectious vaginitis.

Abstract

To compare the Affirm VPIII molecular test

(Becton Dickinson, Burlington, NC) with morphologic

identification used in routine Papanicolaou (Pap) test

screening in the detection and identification of Candida

species, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Gardnerella

vaginalis, we identified 431 cases with a concomitant

Pap test and Affirm VPIII assay performed from the

archives of a large academic institution. The study

population consisted of women ranging in age from 17

to 79 years (mean and median ages, 33 and 31 years,

respectively). With a routine Pap test, 60 patients

(13.9%) were found to have bacterial vaginosis, 60

(13.9%) candidiasis, and 3 (0.7%) Trichomonas

infection. With the Affirm VPIII assay, 183 (42.5%)

patients tested positive for G vaginalis, 70 (16.2%)

positive for Candida species, and 10 (2.3%) positive

for T vaginalis. The differences were statistically

significant. The results demonstrate that our patient

population had a high incidence of bacterial vaginosis/

Candida vaginitis; however, the Affirm VPIII was a

more sensitive diagnostic test for the detection and

identification of all 3 organisms compared with the Pap

test.

442

442

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

The ASCP is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing

Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The ASCP designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA

Category 1 Credit per article. This activity qualifies as an American Board

of Pathology Maintenance of Certification Part II Self-Assessment Module.

The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff

have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose.

Questions appear on p 479. Exam is located at www.ascp.org/ajcpcme.

Infectious vaginitis is one of the most common

womens health care problems in the United States.1 The

3 leading microbial agents that are responsible for 90%

of infectious vaginitis are the organisms causing bacterial

vaginosis (BV), Candida species, and Trichomonas vaginalis.2 Although BV is characterized by a mixed infection

of anaerobic bacteria, Gardnerella vaginalis is considered

one of the major bacteria causing this infection.3 Optimal

treatment relies on the correct identification of these

organisms.

Clinical diagnosis of infectious vaginitis relies on

physical examination and a number of tests, such as microscopic examination, pH testing of vaginal fluid, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) amine odor test, performed at the

point of care. However, such tests are often time-consuming

and somewhat subjective. The Papanicolaou (Pap) test has

become a routine procedure for women at their annual

gynecologic visit because of its success in the prevention

of cervical cancer and precursor lesions. In addition to its

primary benefit as a cancer screening test, other benefits of

the Pap test include the detection of cervicovaginal microorganisms. However, the use of Pap tests to diagnose infectious vaginitis remains controversial.4,5

Recently, a molecular test, Affirm VPIII assay (Becton

Dickinson, Burlington, NC) to detect and specifically identify Candida species, G vaginalis, and T vaginalis from

vaginal fluid specimens has become commercially available. Preliminary results are promising.6-9 The objective

of this study was to compare the Affirm VPIII molecular

test with morphologic identification used in routine Pap

test screening in the detection and identification of these

3 organisms.

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Anatomic Pathology / Original Article

Materials and Methods

Patients who had a Pap test and concomitant Affirm VPIII

molecular testing between August 2008 and March 2009 were

included in this institutional-approved study. Patients who had

Affirm VPIII molecular testing not accompanied by a Pap test

were excluded from the study. The specimens were submitted

by a dozen community-based gynecologists.

All Pap tests were liquid-based preparations; 20% were

ThinPrep (Hologic, Marlboro, MA), and the remaining 80%

were SurePath (Becton Dickinson). The Pap tests were not

initially identified as part of a study because the cytotechnologists and cytopathologists were blinded to the results of the

molecular testing. A diagnosis of BV was made based on the

presence of the following 3 findings: a filmy background of

small coccobacilli, individual squamous cells coated with a

layer of coccobacilli along the cell membranes (so-called clue

cells), and conspicuous absence of lactobacilli10 Image 1. A

diagnosis of Candida infection was made by the identification

of yeast and pseudohyphae Image 2, whereas a diagnosis

of Trichomonas infection was made by the identification of

15- to 30-m, pear-shaped structures with a centrally located

nucleus Image 3.

The samples for the Affirm VPIII molecular test were

collected from the posterior fornix and side walls of the

vagina using a sterile swab. The swab was then placed into

an inactivation medium provided by the vendor (Becton

Dickinson). The medium is designed to preserve the nucleic

acid of microorganisms during specimen transport at room

temperature for up to 72 hours.

Image 1 Individual squamous cells coated with a layer of

coccobacilli along the cell membranes (so-called clue cells)

and conspicuous absence of lactobacilli characteristic of

bacterial vaginosis (Papanicolaou, 400).

The swabs were then tested using the Affirm VPIII

assay on the BD MicroProbe Processor (Becton Dickinson)

according to the manufacturers recommendations. The test

is based on the principle of nucleic acid hybridization in

which complementary nucleic acid strands align to form specific, double-stranded complexes called hybrids. The system

uses 2 distinct single-stranded probes that are complementary to unique genetic sequences of each target organism,

a capture probe, and a color-development probe. The capture probe is immobilized on a bead embedded in a Probe

Analysis Card (Becton Dickinson). The Probe Analysis

Card contains a separate bead for each target organism.

The color-development probes are contained in a multiwell

reagent cassette.

The assay consists of the following 3 steps: denaturing

of the samples to release each target organisms genetically unique nuclei acids, automated assay processing, and

recording of the results after 30 minutes. The assay includes

positive and negative controls on each Probe Analysis Card,

which are tested simultaneously with each patient sample.

After completion of molecular testing, the results of the

Affirm VPIII assay were visually observed and recorded

Image 4.

Pap tests with results that were discrepant from those of

the Affirm VPIII were manually rescreened by a cytotechnologist who was blinded to the results of the original Pap

test interpretation and the molecular test results. Statistical

analysis was performed by using the 2 test and Fisher exact

test. Statistical significance was set at a level of .05 or less.

Image 2 Pseudohyphae characteristic of Candida species

formed by elongated budding hyphae with constrictions along

their length (Papanicolaou, 400).

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

443

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

443

443

Levi et al / Molecular Testing of Infectious Vaginitis

Image 3 Trichomonas vaginalis (Papanicolaou, 400). Pearshaped, 15- to 30-m structures with a centrally located

nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules. Leptothrix

may be seen in association with Trichomonas.

Image 4 Affirm VPIII Probe Analysis Card for 2 patient

samples. The Probe Analysis Card on top is visually interpreted

as positive for Candida; the Probe Analysis Card on the bottom

is positive for Gardnerella. Each Probe Card includes positive

and negative controls for each patient sample.

We used the statistic to evaluate chance-corrected agreement between the Pap test and the Affirm VPIII assay. A

value of 0 indicates that the observed agreement is the same

as expected by chance, whereas a value of 1 indicates

perfect agreement. The values between 0 and 1 represent the

various extents of agreement as follows: a value of less than

0.2 indicates poor agreement; 0.21 to 0.6, fair to moderate

agreement; 0.61 to 0.8, good agreement; and 0.81 to 1.0,

excellent agreement.11

positive for Gardnerella and Trichomonas. One case was

positive for all 3 organisms with the Affirm VPIII assay.

Coinfection by 2 or more organisms was noted in only 5

cases based on Pap test evaluation. Of the 5 cases, 4 had

BV and candidiasis, and 1 had candidiasis and Trichomonas

infection. No cases were found to have all 3 organisms using

the Pap test.

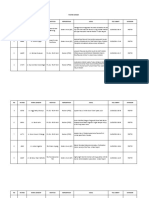

Of the 431 cases with Pap and Affirm VPIII test results,

154 had discrepant cytologic and molecular test results with

regard to the detection and identification of 1 or more of the

3 organisms. Among these 154 discrepant cases, 136 had a

positive molecular test result but a negative cytologic result.

Among the latter, the Affirm VPIII identified 127 cases of

Gardnerella infection, 25 of candidiasis, and 7 of trichomoniasis. On rescreening of the Pap slides, BV was identified in

41 cases, candidiasis in 8, and trichomoniasis in 3 that were

missed by initial cytologic screening.

There were 18 cases in which the Pap tests reported the

presence of organisms, including 13 cases of Candida, 4 of

BV, and 1 of Trichomonas, but the corresponding molecular test results were negative. On rescreening, 8 cases of

candidiasis and 2 of BV were confirmed on the Pap tests.

The case of trichomoniasis negative by molecular testing

was not confirmed by rescreening; the slide demonstrated

extensive cytolysis with many naked nuclei that could have

been misinterpreted as Trichomonas. The Pap tests that were

overinterpreted for BV demonstrated a filmy background

of cocci but lacked evidence of clue cells.

Results

The study included 431 cases. The age of the participants

ranged from 17 to 79 years with a mean of 33 years. With

the Pap test, 60 patients (13.9%) were found to have BV, 60

(13.9%) had candidiasis, and 3 (0.7%) had a Trichomonas

infection. With the Affirm VPIII assay, 183 (42.5%) cases

tested positive for G vaginalis, 70 (16.2%) were positive for

Candida species, and 10 (2.3%) were positive for T vaginalis. The differences were statistically significant.

The diagnosis of Candida infection by Pap test agreed

well with the result of the Affirm VPIII assay ( = 0.66).

There was poor agreement for the diagnosis of BV ( = 0.32)

and Trichomonas infection ( = 0.30).

Coinfection by 2 organisms was noted in 30 cases by

using the Affirm VPIII assay; 26 cases tested positive for

Gardnerella and Candida, and the remaining 4 cases were

444

444

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Anatomic Pathology / Original Article

Discussion

Infectious vaginitis is a common medical problem in

women.1 The organisms that cause BV, fungi (candidiasis),

and parasites (T vaginalis) are the 3 leading microbial agents

that are responsible for 90% of all infectious vaginitis. It has

been reported that three quarters of adult women will experience at least 1 episode of vaginal candidiasis during their

lifetimes and about half of the women will have 2 or more

episodes.12 Although the incidence of Trichomonas infection

has been declining for the past 20 years, more than 7.5 million

new cases of Trichomonas infection are reported each year in

the United States.13 BV occurs in up to 30% of the population

and is more common in African Americans than Caucasians

by a factor of 3.14 Although affected patients are often concerned by the troubling symptoms, there are also considerable

morbidities associated with infectious vaginitis. For example,

patients with BV have an enhanced risk of developing postoperative infection after pelvic surgery.14 BV and trichomoniasis

have been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such

as premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and

low birth weight.12

The error rate in diagnosing infectious vaginitis using

traditional methods is rather high. Based on clinical signs

and symptoms and bedside testing, including wet mount

microscopy, KOH amine odor test, and a pH test of vaginal

fluid, about two thirds of the cases of Candida and BV were

misdiagnosed by general practitioners and gynecologists in a

cohort of 220 women with vaginal complaints.7 The authors

attributed the error rate to the lack of microscopy-related skills

and the subjectivity of some of the diagnostic criteria. Other

factors that were noted to have contributed to a misdiagnosis included menstruation, douching, and self-medication.

Furthermore, infectious vaginitis can be asymptomatic in as

high as 50% of cases.15 In another study by Lowe et al,16

the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of BV, Candida vaginitis, and T vaginalis was compared with the Affirm VPIII

DNA probe molecular test for G vaginalis, T vaginalis, and

Candida species. Lowe et al16 found that compared with the

DNA probe standard using the Affirm VPIII, clinical diagnosis is 81% to 85% sensitive and 70% to 99% specific for BV,

Candida vaginitis, and trichomoniasis. While using traditional

standardized clinical diagnostic protocols even under the best

of circumstances, the diagnosis and treatment of these common vaginal problems remains challenging.16

Some authors advocate the use of Gram stain in the diagnosis of BV.3 However, Gram stain diagnosis ranged from

60% to 90% compared with the clinical diagnosis of BV.17-19

Microbial culture is another technique that can be useful in the

diagnosis of vaginitis and vaginosis. Culture for Trichomonas

is highly effective and relatively inexpensive.19,20 However, it

lacks clinical usefulness because it requires a special medium

(Diamond), which is not uniformly available, and an extended

turnaround time of up to 5 days. Cultures for Gardnerella and

Candida species are not recommended because both organisms can be part of the normal vaginal flora without causing

any infection.15,17,19

Because of the success of reducing the incidence and

mortality of cervical squamous carcinoma, Pap tests have

been widely adopted in the United States and other developed

countries. One of the secondary benefits is the detection of

microorganisms. As a result, many clinicians have come to

rely on the identification of microorganisms by the routine

Pap test as part of their patient management.5 The sensitivity

of Pap tests for diagnosing BV varies from 90% to as low

as 43%; the wide range of results reflects the use of different morphologic criteria and whether the specimens were

obtained from the cervix or the vagina.5,21-25 Similarly, the

Pap test lacks sensitivity as a screening test for Trichomonas.

Moreover, in low-prevalence populations, Trichomonas found

by cytomorphologic review and reported by routine Pap testing frequently represented a false-positive result.3

There has been an increase in the use of imaging systems

for primary screening of Pap tests. For a small portion of

scanned slides, no manual review would be performed (if no

abnormalities were noted in the fields selected by the system)

or only a limited number of fields would be examined (if the

system ranks the slides with a low probability of containing

abnormalities) depending on the type of imaging system being

used. This may result in underdetection of infections. One

study observed that the detection rates of Candida (68% vs

77%), Trichomonas (80% vs 85%), and shift in bacterial flora

(63% vs 65%) were lower with the AutoPap imaging system

(Becton Dickinson) compared with manual screening.26

To address these difficulties, a rapid and sensitive tool

is needed. The Affirm VPIII assay allows the simultaneous detection of the presence of clinically significant levels

of Trichomonas, Gardnerella, and Candida from vaginal

specimens. The results of our study show that the Affirm

VPIII assay demonstrated significantly higher detection rates

for all 3 organisms compared with Pap tests. The difference

in the detection rate of Gardnerella between the Affirm VPIII

assay and the Pap test was the most pronounced. One plausible

explanation is that the Pap test is essentially a cervical specimen, while BV is essentially a vaginal condition. Therefore,

BV is more likely to be better represented by vaginal samples

used in the Affirm VPIII assay.27 We also observed poor

agreement between the Affirm VPIII assay and the Pap test

when identifying Trichomonas. As mentioned earlier, in

populations like ours with a low prevalence of Trichomonas, a

higher incidence of false-negatives and false-positives may be

noted in the reporting of Trichomonas by gynecologic cytology staff.3 Therefore, our findings suggest that the Affirm

VPIII assay is more sensitive than the Pap test as a diagnostic

tool for the detection and identification of infectious vaginitis.

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

445

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

445

445

Levi et al / Molecular Testing of Infectious Vaginitis

This argument supported the results of rescreening of the Pap

slides with discrepant cytologic and molecular test results.

Organisms were identified on rescreening in about one third of

the cytologic specimens that were initially reported to be negative for organisms but had positive molecular test results.

Our observation is comparable to findings from studies

that compared the Affirm VPIII assay with other methods

of detection of these 3 organisms.6-9,28,29 Based on a cohort

of 425 women, Brown et al6 demonstrated that the Affirm

VPIII assay was significantly more sensitive than wet mount

in identifying Candida (11% vs 7%) and Gardnerella (45%

vs 14%). The Affirm VPIII assay also detected more cases

of Trichomonas infection compared with wet mount (7% vs

5%), but the difference was not statistically significant.6 It has

also been reported that the Affirm VPIII assay correlated well

with the Gram stain in diagnosing BV and candidiasis.9,28,29

Because Gardnerella and Candida species can exist as

normal flora in 50% of women, a too sensitive molecular

diagnostic test may yield false-positive results, resulting in

unnecessary treatment.3,30 To minimize the possibility of

false-positive cases due to microbial colonization, the detection thresholds of the Affirm VPIII assay for each organism

are set above the levels of normal flora, thus ensuring that

only clinically relevant cases are detected. According to

the manufacturer, the detection thresholds for Gardnerella,

Candida, and Trichomonas species are 2 105 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, 1 104 CFU/mL, and 5 103 CFU/mL,

respectively.31 This may explain some of our false-negative

molecular test results despite a positive cytologic result.

Based on personal communications with clinicians, our clients as a whole use the Affirm VPIII molecular test when

there is a clinical symptom that is reported by the patient and/

or a clinical sign noted during the gynecologic examination.

Depending on the provider, in some cases, before ordering

the molecular test, other diagnostic tools for vaginosis and

vaginitis, such as a wet mount, may be prepared in the office,

although much less commonly given the time constraints of

office practice and diminishing skill sets. If the bedside pointof-care tests are interpreted as negative, then the Affirm VPIII

test is ordered. As a general treatment protocol practiced by

our clients, patients with a clinical symptom and/or sign of

vaginitis or vaginosis in the setting of a positive result for a

given organism(s) (including the Affirm VPIII molecular test

result, a wet mount microscopic examination result, and/or

a positive Pap test result) are offered treatment for the given

organism(s) detected. Using the results of the Affirm VPIII

molecular test in addition to the routine Pap test in cases in

which there is a clinical suspicion of vaginitis or vaginosis

may decrease the likelihood of potential false-positive results

and unnecessary treatment.

About 14% of patients with infectious vaginitis have a

mixed infection.32 In our study, the Affirm VPIII assay identified

446

446

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

30 patients (7.0%) with coinfection by 2 or more microorganisms, whereas the Pap test identified only 5 patients (1.2%)

with coinfection by 2 microorganisms. The difference was

statistically significant (Fisher exact test). In addition, cytologic

rescreening detected only 1 additional case of coinfection by 2

pathogens in the positive for Trichomonas and Gardnerella

category. Our findings suggest that the Affirm VPIII assay is

superior to the Pap test in detecting multiple pathogens.

There are other advantages of the Affirm VPIII assay

over the Pap test, including the objectivity of the assay, the

elimination of the need for special microscopy skills, and the

quick turnaround time of less than 2 hours. Also, there is no

interference with the assay by over-the-counter medications,

lubricants, douching, or menstruation. The specimen transport

medium preserves the specimens up to 72 hours from collection at room temperature, thereby facilitating transportation

from the physician office to the laboratory.6

One of the limitations of our study is that we were not

able to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of the Affirm

VPIII assay and Pap tests because we did not compare our

results with the gold standards such as microbial cultures

or Gram stain. Other studies reported that the sensitivity

and specificity of the Affirm VPIII assay in identifying G

vaginalis ranged from 88% to 90% and from 96% to 97%,

respectively.28,29 For diagnosing Candida species using the

Affirm VPIII assay, Petrikkos et al9 reported a sensitivity of

82% and specificity of 100% when compared with examination using 10% KOH.

We demonstrated that the Affirm VPIII assay using a

DNA hybridization technique was more sensitive in identifying G vaginalis, Candida species, and T vaginalis than the Pap

test. In addition, mixed infection is more readily diagnosed by

the Affirm VPIII assay than the Pap test.

From the Department of Pathology, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Address reprint requests to Dr Levi: 430 Congress Ave, New

Haven, CT 06519.

References

1. Kent HL. Epidemiology of vaginitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1991;165(4 pt 2):1168-1176.

2. Fleury FJ. Adult vaginitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol.

1981;24:407-438.

3. Sobel JD, Schmitt C, Meriwether C. A new slide latex

agglutination test for the diagnosis of acute Candida vaginitis.

Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:323-325.

4. Giacomini G, Calcinai A, Moretti D, et al. Accuracy

of cervical/vaginal cytology in the diagnosis of bacterial

vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:24-27.

5. Platz-Christensen JJ, Larsson PG, Sundstrom E, et al.

Detection of bacterial vaginosis in wet mount, Papanicolaou

stained vaginal smears and in Gram stained smears. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:67-70.

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Anatomic Pathology / Original Article

6. Brown HL, Fuller DD, Jasper LT, et al. Clinical evaluation

of Affirm VPIII in the detection and identification of

Trichomonas vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Candida

species in vaginitis/vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol.

2004;12:17-21.

7. Schwiertz A, Taras D, Rusch K, et al. Throwing the dice

for the diagnosis of vaginal complaints? Ann Clin Microbiol

Antimicrob. 2006;5:4. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-5-4.

8. Pappas S, Makrilakis K, Anyfantis I, et al. Clinical evaluation

of Affirm VP III in the detection and identification of

bacterial vaginosis [letter]. J Chemother. 2008;20:764-765.

9. Petrikkos G, Makrilakis K, Pappas S. Affirm VP III in the

detection and identification of Candida species in vaginitis.

Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96:39-40.

10. Young NA, Bibbo M, Buckner S, et al. Non-neoplastic

findings. In: Solomon D, Nayar R, eds. The Bethesda System

for Reporting Cervical Cytology. 2nd ed. New York, NY:

Springer; 2004:21-56.

11. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing

agreement between two methods of clinical measurement.

Lancet. 1986;1:307-310.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted

diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep.

2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trichomoniasis:

CDC Fact Sheet. 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/

STDFact-Trichomoniasis.htm#Common. Accessed January

21, 2011.

14. Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: an overview for 2009.

Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:28-37.

15. Carr PL, Felsenstein D, Friedman RH. Evaluation and

management of vaginitis. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:335-346.

16. Lowe NK, Neal JL, Ryan-Wenger NA. Accuracy of the

clinical diagnosis of vaginitis compared to a DNA probe

laboratory standard. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:89-95.

17. Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Comparison of

methods for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis among pregnant

women. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1266-1271.

18. Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, et al. Diagnosis and

clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 1988;158:819-828.

19. Spiegel CA, Amsel R, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of bacterial

vaginosis by direct Gram stain of vaginal fluid. J Clin

Microbiol. 1983;18:170-177.

20. Fouts AC, Kraus SJ. Trichomonas vaginalis: reevaluation of its

clinical presentation and laboratory diagnosis. J Infect Dis.

1980;141:137-143.

21. Schnadig VJ, Davie KD, Shafer SK, et al. The cytologist and

bacterioses of the vaginal-ectocervical area: clues, commas

and confusion. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:287-297.

22. Davis JD, Connor EE, Clark P, et al. Correlation between

cervical cytologic results and Gram stain as diagnostic

tests for bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1997;177:532-535.

23. Hillier SL. Diagnostic microbiology of bacterial vaginosis.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(2 pt 2):455-459.

24. Tokyol C, Aktepe OC, Cevrioglu AS, et al. Bacterial

vaginosis: comparison of Pap smear and microbiological test

results. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:857-860.

25. Eriksson K, Forsum U, Bjornerem A, et al. Validation of the

use of Pap-stained vaginal smears for diagnosis of bacterial

vaginosis. APMIS. 2007;115:809-813.

26. Wilbur DC, Prey MU, Miller WM, et al. AutoPap system

detection of infections and benign cellular changes: results

from primary screener clinical trials. Diagn Cytopathol.

1999;21:355-358.

27. Karani A, De Vuyst H, Luchters S, et al. The Pap smear

for detection of bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet.

2007;98:20-23.

28. Witt A, Petricevic L, Kaufmann U, et al. DNA hybridization

test: rapid diagnostic tool for excluding bacterial vaginosis in

pregnant women with symptoms suggestive of infection.

J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3057-3059.

29. Gazi H, Degerli K, Kurt O, et al. Use of DNA hybridization

test for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis in women with

symptoms suggestive of infection. APMIS. 2006;114:784-787.

30. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing

bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of

Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

31. Affirm VP III Assay [package insert]. Burlington, NC: Becton

Dickinson; 2009.

32. Ferris DG, Hendrich J, Payne PM, et al. Office laboratory

diagnosis of vaginitis: clinician-performed tests compared

with a rapid nucleic acid hybridization test. J Fam Pract.

1995;41:575-581.

American Society for Clinical Pathology

Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:442-447

447

DOI: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU

447

447

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Formulation and Evaluation of Ibuprofen Topical GEL: Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, KarnatakaDocument12 paginiFormulation and Evaluation of Ibuprofen Topical GEL: Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore, Karnatakagina inÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kelompok 10Document24 paginiKelompok 10Nining FauziahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Expert Systems - MYCINDocument8 paginiIntroduction To Expert Systems - MYCINVictoria OffomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HYDRALAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE - (Apresoline)Document1 paginăHYDRALAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE - (Apresoline)wen_pilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abnormal Psych Question 1Document10 paginiAbnormal Psych Question 1Ronald Jacob Picorro100% (1)

- Liverpool SDL IABPDocument26 paginiLiverpool SDL IABPSathya Swaroop PatnaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 5 Levels of Healing - A Guide To Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument1 paginăThe 5 Levels of Healing - A Guide To Diagnosis and TreatmentJAYAKUMAR100% (1)

- Enoxaparin FDADocument40 paginiEnoxaparin FDAImam Nur Alif Khusnudin100% (2)

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing 2nd EditionDocument550 paginiPsychiatric Mental Health Nursing 2nd Editiondaria100% (7)

- 5 Day Bodybuilding Workout ScheduleDocument4 pagini5 Day Bodybuilding Workout ScheduleNazri Yusoff100% (1)

- Common Cancers in WomenDocument27 paginiCommon Cancers in Womensuha damagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Issues & Trends in Older: Persons Chronic CareDocument12 paginiCurrent Issues & Trends in Older: Persons Chronic CareKeepItSecretÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Talk - Diet in AnemiaDocument17 paginiHealth Talk - Diet in Anemiameghana88% (8)

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)Document14 paginiDisruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)David PÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRCPass Notes For MRCP 1 - HEMATOLOGYDocument9 paginiMRCPass Notes For MRCP 1 - HEMATOLOGYsabdali100% (1)

- Vitamin B12 DeficiencyDocument2 paginiVitamin B12 DeficiencyFarina AcostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgery Report & RatingsDocument25 paginiSurgery Report & RatingsWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Use BNF With ScenariosDocument6 paginiHow To Use BNF With ScenariosLuxs23Încă nu există evaluări

- Cystic Fibrosis Patient PamphletDocument2 paginiCystic Fibrosis Patient PamphletfloapaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electric Field Distribution in Biological Tissues For Various Electrode Configurations - A FEMLAB StudyDocument5 paginiElectric Field Distribution in Biological Tissues For Various Electrode Configurations - A FEMLAB StudyxlippyfingersÎncă nu există evaluări

- S1 Hippocratic Oath Seminar and Reading NotesDocument7 paginiS1 Hippocratic Oath Seminar and Reading NotesTaraSubba1995Încă nu există evaluări

- Elizabeth L. Samonte BSN Iv Responsibilities of The Nurse To The PatientsDocument7 paginiElizabeth L. Samonte BSN Iv Responsibilities of The Nurse To The PatientsRein VillanuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Konker AbstractDocument39 paginiKonker AbstractWigunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Through PlayDocument2 paginiLearning Through PlayThe American Occupational Therapy Association100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan For Osteomyelitis: Nursing Diagnosis For Osteomyelitis and Nursing Interventions For OsteomyelitisDocument43 paginiNursing Care Plan For Osteomyelitis: Nursing Diagnosis For Osteomyelitis and Nursing Interventions For Osteomyelitisabe abdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are Mucous CystsDocument10 paginiWhat Are Mucous CystsNena TamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diabetes and Its Permanent Cure With Homeopathic Medicines - DRDocument28 paginiDiabetes and Its Permanent Cure With Homeopathic Medicines - DRkrishna kumar67% (3)

- RanbaxyDocument5 paginiRanbaxy26449659Încă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Surgery NotesDocument214 paginiClinical Surgery Notessarahsarahsarahsarah100% (6)

- Prescription of Exercise For Health and FitnessDocument27 paginiPrescription of Exercise For Health and FitnessedelinÎncă nu există evaluări