Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

T 203

Încărcat de

oradev-1Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

T 203

Încărcat de

oradev-1Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

luxuries, fell.

English working people now ate wheat bread, rather than rye

bread, and could afford and obtain small self-indulgences such as ribbons,

laces, mirrors, toys, combs, and the like: a skilled worker in eighteenthcentury

London had the financial means to buy not only cheap print ballads and chapbooks - but even substantial novels selling at six shillings

a copy. Thanks to the growth of Britain's sea-borne trade, exotic luxuries

such as fruit, coffee, tea, sugar, fabrics, and tobacco were arriving from the

East and from the plantations of the New World. The stocks of provincial

shopkeepers are testimony to the spread of gracious living, sophistication,

and luxury to the country towns of Augustan England.

In what Peter Borsay dubs an "urban renaissance" the towns of England

and Wales changed their style, ambience, even their functions, in this

period. In short they became centers for leisure, civility, and consumption.

Instead of being simply markets or industrial centers, towns became

meeting places for the gentry and those who aspired to that status, for

professionals, and for those who had made their money and now wished to

enjoy it. Some of these towns such as Bath or Tunbridge Wells, made a

speciality of leisure and became resorts, while others amalgamated functions.

Whether the measure is the number of coffee-houses, daily and

provincial newspapers, libraries or horse-race meetings, there is no denying

the explosion of places to go and things to do and see in Augustan England.

Towns became centers of polite living because there existed a leisured class,

a majority of whom were female, who had the time to devote to teadrinking,

dancing, and cards, and the wealth to invest in the various

purpose-built Assembly rooms and concert halls, parks, and civic amenities.

And this leisured class deliberately chose to devote itself to civility as a

means of creating a tolerant and tolerable, civilized and stable society.

A civil society

Civility is not just a product of superfluous wealth and leisure; it is created

and sustained by cultural means, by practices which we might label as

discursive or ideological. This is apparent, for instance, in the way in which

Augustan England constructed notions of human nature. In this selfconscious

"age of reason," human psychology was read against its irrational

antithesis, "fanaticism" or "enthusiasm." Several different contemporary

discourses - medical, scientific, religious, cultural, literary, and

political - converged, and "in stressing the connection between enthusiasm,

passions and melancholy, a clear psychological norm was offered as the

basis for the social order: the sober, reasonable and self-controlled

person."34 Such human beings deserved freedom of intellectual inquiry and

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- BN Mutto v. TK NandiDocument11 paginiBN Mutto v. TK NandiAastha JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Old Man and The SeaDocument4 paginiThe Old Man and The Seaapi-295870217100% (2)

- Book Upload 2 Units 2.1-2.10Document21 paginiBook Upload 2 Units 2.1-2.10Jaieir RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustained Silent ReadingDocument3 paginiSustained Silent ReadingFakhriyah SaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Automatic Pistol Neuhausen SP 47-8 (Sig P210) ManualDocument13 paginiAutomatic Pistol Neuhausen SP 47-8 (Sig P210) Manualfalcom2Încă nu există evaluări

- Whey Protein Nitrogen Index A21aDocument6 paginiWhey Protein Nitrogen Index A21aDinesh Kumar BansalÎncă nu există evaluări

- South African Art Times July 2013Document32 paginiSouth African Art Times July 2013Godblessus99Încă nu există evaluări

- Why We Listen To What "They" SayDocument14 paginiWhy We Listen To What "They" Sayfuwad84Încă nu există evaluări

- F Nd-NdeDocument20 paginiF Nd-Nde17011 AKANKSHA MATHURÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Jon Krakauer's Credibility Problem" (Ver. 2.4.6) April 24, 2011 Last Updated 3-20-14Document177 pagini"Jon Krakauer's Credibility Problem" (Ver. 2.4.6) April 24, 2011 Last Updated 3-20-14Guy Montag0% (6)

- IEEE Referencing For Word 2007 + 2010 - MikemurkoDocument12 paginiIEEE Referencing For Word 2007 + 2010 - MikemurkoAntony Ferrer41% (22)

- Build A BaddieDocument9 paginiBuild A BaddieemilmhpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tendering and Bidding ProcessDocument19 paginiTendering and Bidding ProcessSujan SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pet Sample Test Reading 2020Document11 paginiPet Sample Test Reading 2020Pedagógico CNA Campina GrandeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bout Author Ahida INA: Diary in Rasrang, Sunday Magazine of India's Largest Read Hindi Newspaper DainikDocument3 paginiBout Author Ahida INA: Diary in Rasrang, Sunday Magazine of India's Largest Read Hindi Newspaper DainikSandeep GummallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Bibliography FinalDocument25 paginiAnnotated Bibliography Finalapi-302337325Încă nu există evaluări

- Ago14 PreviewsDocument592 paginiAgo14 PreviewsDiego DelgadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abrsm Beethoven PDFDocument18 paginiAbrsm Beethoven PDFGiusy Esposto80% (15)

- Shelter Island Classifieds and Homeowners' NetworkDocument3 paginiShelter Island Classifieds and Homeowners' NetworkTimesreviewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson - Magazine ArticlesDocument3 paginiLesson - Magazine Articlesapi-545873065Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis Trumpet SwanDocument57 paginiAnalysis Trumpet SwanEJ100% (2)

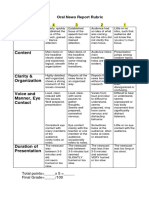

- News Report RubricDocument1 paginăNews Report RubricJobell Aguvida70% (10)

- Sherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Document12 paginiSherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Fernanda SerralÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7.18.19 Thermopolis Independent RecordDocument18 pagini7.18.19 Thermopolis Independent RecordLara LoveÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Broadcasting History of Malaysia Progress and SHDocument9 paginiA Broadcasting History of Malaysia Progress and SHMarliza Abdul MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Posting Journal Entries To The LedgerDocument14 paginiPosting Journal Entries To The LedgerJeanlyn Vallejos DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gatsbyprojects IdeasDocument1 paginăGatsbyprojects Ideasapi-315693371Încă nu există evaluări

- Bo 70 de Thi Vao Lop 10 THPTDocument169 paginiBo 70 de Thi Vao Lop 10 THPTHaoTran199667% (3)

- Analysis of A Semi-Rigid Connection For Precast ConcreteDocument11 paginiAnalysis of A Semi-Rigid Connection For Precast Concretepavan2deepuakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Textbook Ebook The Foiled Plan War of Sins Book 2 Veronica Lancet All Chapter PDFDocument43 paginiTextbook Ebook The Foiled Plan War of Sins Book 2 Veronica Lancet All Chapter PDFguy.jennings945100% (10)