Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Dumitriu, Anton. History of Logic 370-371

Încărcat de

stefanpopescu574804Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dumitriu, Anton. History of Logic 370-371

Încărcat de

stefanpopescu574804Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

History of Logic by Anton Dumitriu

The Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Jun., 1980), pp. 370-371

Published by: Association for Symbolic Logic

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2273199 .

Accessed: 04/08/2013 15:39

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Symbolic Logic is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Symbolic Logic.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.49.23.145 on Sun, 4 Aug 2013 15:39:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

370

REVIEWS

rather a viewing of clippings from the original reels. The result is, as one would expect, that he

has produced a report rather than a history; it is often full of welcome and little-known details of

history of logic, but interpretation is bland or even non-existent. The cast of the net has also been

rather too wide. For example, the chapters on the application of logic to twentieth-century problems embrace quantum mechanics, relativity, dialectics, linguistic philosophy, induction, and the

logic of scientific discovery; fifty sections have only pages 62-132 of Volume III to make their

points, so that each section is too brief to state satisfactorily either the logic involved or the application being made. The same criticism applies to Dumitriu's rapid presentation of the postRomantic logicians (Vol. III, pp. 235-259) and their psychologistic contemporaries (Vol. III, pp.

311-352).

Dumitriu's historiography is put to a severe test in the last volume, for the history of mathematical logic has been fraught with controversies over the nature of logic and its relationship with

set theory and mathematics in general, and handicapped by the slow recognition of metalogic as

separate from logic. How would a film director cope with this? The chapter on algebraic logic

(pp. 39-50) is exceedingly disappointing; the usual things (but nothing else) are said about Boole,

Peirce receives just over a page, Schroder thirteen lines. Among the later developments, those on

many-valued logics (including modal logics, pp. 145-181) and formalism and proof theory (pp.

182-223) include some longer takes, though the text usually reads like a script (A did this, B did

that, and so on). And regrettably, some developments that have aroused great interest are either

ignored or given only the briefest exposure: for example, the substitutional interpretation of

quantification (indeed, little is said about quantification anywhere), free logic, natural deduction

(five lines on p. 143, with Popper's contributions overlooked), and Quine's logical systems (eight

lines on p. 141). No points of substance are made anywhere about Cantor or Lesniewski, despite

the variety of their influences on logic; the absence of Lesniewski from the chapter on the paradoxes

and their solutions (pp. 113-117) is particularly painful.

In the more substantial chapters, only the familiar scenes are shown. The Frege chapter (pp.

51-63) is devoted largely to the elementary parts of his symbolism; there is not even an indication

of how his logicist thesis is articulated. The Peano chapter (pp. 64-86) similarly runs over the

logical, set-theoretical, and arithmetical notions, though there is also a useful passage on Peano's

attention to definitions (pp. 77-80). The chapter on Principia mathematics

(pp. 87-112) involves a

basic mistake for any history of logic: The prehistory of the work in Russell and Whitehead's

earlier writings is overlooked, with the result that the motivations to its principal ideas are lacking.

Judgements, when made at all, are tendentious. For example, on pages 88-89 the need to axiomatise logic is ascribed to Hilbert's influence, whereas Russell was so removed from Hilbert's views

that he did not even assess the consistency and independence of his axiom system. Again, the

critical comments on Russell's admittedly curious remarks on definitions (p. 111) overlook the

important use made in Principia mathematics of contextual definition.

The above assessment is presented with a keen sense of my own ingratitude. I have done enough

historical study to know how much hard work it involves, and the labour required here from

author, translators, and publisher to put nearly thirteen hundred pages on the market must have

been immense. Yet the result is disappointing, chiefly because of Dumitriu's conception of his

task, with his "open book" view that the texts alone, or condensed versions of them, will constitute

a history of logic. He quotes with approval Aristotle's comment that "he who does not philosophize, philosophizes" (Vol. I, p. x), but he himself exemplifies the rider that such inexplicit philosophy can be the least valuable of all.

If I were to compare this history with its predecessors, then I would describe it as "Bocheiiski

writ large." Those familiar with Bochefiski's History of formal logic (cf. XXV 57) will recall the

cinematographic style used there-brief extracts strung together, newsreel-style, as sequences of

short takes. Dumitriu summarises more than he quotes, but the effect is the same. Bochefiski's

readers are also grateful for his extensive bibliographies and indexes, and by and large they are

well served by Dumitriu also. Neither author, however, allows himself to go beyond these limitswhich is a pity, for beyond film-watching is creative film-writing, where history becomes interesting

and important.

I. GRATTAN-GUINNESS

ANTON

DUMITRIU.

Istoria logical. Editura Didacticg ?i Pedagogici, Bucharest 1969, 1049

pp.

This content downloaded from 129.49.23.145 on Sun, 4 Aug 2013 15:39:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS

371

ANTON DUMITRIU. Istoria logicii. Second, revised and enlarged, edition of the preceding and

Roumanian original of History of logic. Editura Didacticd ?i Pedagogicd, Bucharest 1975, 1212

PP.

Librairie

ROBERT BLANCHE. La Logique et son histoire: d'Aristote a' Russell. Collection U.

Armand Colin, Paris 1970, 366 p.

Il n'existait jusqu'ici aucune histoire de la logique un peu developpee due a un auteur de langue

franqaise. L'ouvrage de Robert Blanche comble cette lacune pour une periode qui va de la logique

grecque a la naissance de la logique contemporaine. L'ouvrage clairement redige, ecrit dans une

bonne langue, se lit avec plaisir.

Mais il faut bien constater que, en depit du sous-titre, I'auteur a consacre proportionnellement

beaucoup plus de place a la logique classique et aux premieres tentatives de mathematisation de la

logique qu'aux oeuvres de pionniers comme Frege et Russell. Pour tout ce qui concerne la logique

classique l'information est abondante et a jour si l'on tient compte de la date de parution de

l'ouvrage et de son dMlaid'elaboration. L'expose ne neglige ni les commentaires traditionnels ni

les recherches entreprises a la lumiere de la logique mathematique contemporaine. L'auteur s'efforce

de degager une vue synthetique faisant place sans parti pris aux differents apports et il y parvient

souvent avec bonheur. Les chapitres consacres a Aristote, aux megariques, aux stoiciens illustrent

bien sa maniere. De meme la logique medievale, les apports de la Renaissance et Leibniz sont

traits egalement d'agreable faqon.

La situation change quand on aborde la logique posterieure a 1850. La quality de la presentation

demeure. Mais, surtout en ce qui concerne les tres grands noms, l'information semble moins solide.

On peut comprendre qu'a propos de Boole l'auteur n'ait pas voulu entrer dans des details techniques. Il est regrettable que l'amateur de details soit renvoye en tout et pour tout a l'ouvrage de

Liard (1878), Les logiciens anglais contemporains (413), et au Treatise de Jorgensen (4241). De

meme, en ce qui concerne Frege et Russell, l'expose est a la fois acceptable en ce sens, qu'il ne

contient pas d'affirmation erronee, et insuffisant en ce qu'il manque de relief et ignore tout ce que,

depuis bien des annees, les recherches sur Frege et Russell ont apporte.

Des references bien choisies auraient pu aider le lecteur; en fait, au fur et a mesure que l'on

avance vers la fin de l'ouvrage, elles sont de moins en moins nombreuses et de plus en plus arbitrairement choisies.

Malgre ce desequilibre, ce livre rendra de grands services aux etudiants depourvus de culture

mathematique, interesses surtout par la logique ancienne et classique. Pour ce qui concerne les

cent dernieres annees, ils trouveront une esquisse qui ne saurait les dispenser de recourir a des

ROGER MARTIN

etudes plus etoffees.

ALEX ORENSTEIN. Willard Van Orman Quine. Twayne's world leaders series, no. 65.

Twayne Publishers, Boston 1977, 180 pp.

Rather bravely, Orenstein sets out to furnish the uninitiated reader with an integrated view

of Quine's philosophical thought in less than sixty thousand words. The treatment is sympathetic,

the book mainly uncritical. "To a certain extent, the present work is ordered to reflect Quine's

intellectual development." The principal topics are ontological commitment, meaning and reference, logical truth, analyticity, holism, indeterminacy of translation, and behaviorism; there is

little on technical logic.

Presuppositions are meagre; even truth-functions and quantifiers are presented as if they might

be new to the reader. To place Quine's philosophy in perspective, Orenstein supplies the needed

sketches of doctrine from Frege, Russell, Carnap, Tarski, and others. He quotes very liberally

from Quine's own writings. Indeed the reviewer finds that the most successful portions of the book

are those that are thickest with quotation. For it is difficult to improve on Quine through paraphrase, given the lucidity and elegance of his prose.

Orenstein is a responsible expositor of Quine's philosophy. Some of his summaries are sharp

and crisp (as of Duhemian holism and of Quine's clash with Chomsky's innateness hypothesis),

others somewhat cloudy (on observation sentences and on views of '2 plus 2 equals 4'). He is skilled

at keeping his account simple without great sacrifice of accuracy. The book is thoughtfully organized, though there is occasional flitting from topic to topic. As is inevitable in so short a treatment

of so broad a subject, there is some lack of depth. On balance, Orenstein may be seen as moderately

This content downloaded from 129.49.23.145 on Sun, 4 Aug 2013 15:39:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Art Photography Now - Susan BrightDocument231 paginiArt Photography Now - Susan BrightFrancesca Farrah92% (12)

- Wittgenstein's Remarks On The Foundation of MathematicsDocument25 paginiWittgenstein's Remarks On The Foundation of Mathematicsgravitastic100% (1)

- A Companion To Modern British and Irish DramaDocument604 paginiA Companion To Modern British and Irish DramaNikoletta K Olvaso100% (4)

- FROM SHAME TO SIN-The Christian Sexual Morality - (2013) PDFDocument318 paginiFROM SHAME TO SIN-The Christian Sexual Morality - (2013) PDFRonnie Rengiffo100% (4)

- Gadamer y FocaultDocument44 paginiGadamer y FocaultJuan Carlos Sánchez-AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1994 Vlastos G. - Socratic StudiesDocument166 pagini1994 Vlastos G. - Socratic StudiesVildana SelimovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextDocument19 paginiLodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextHumano Ser0% (1)

- TAYLOR, W. 1948. Archaeology - History or AnthropologyDocument11 paginiTAYLOR, W. 1948. Archaeology - History or AnthropologyBiancaOliveira100% (1)

- 100 Ideas That Changed The WorldDocument3 pagini100 Ideas That Changed The WorldЯнаÎncă nu există evaluări

- Man en SILProd 001 OperatorDocument116 paginiMan en SILProd 001 OperatorAhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- John McCarthy - Artificial Intelligence and PhilosophyDocument6 paginiJohn McCarthy - Artificial Intelligence and Philosophykrillin.crillinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Friedman, Michael. Re-Evaluation Logical PositivismDocument16 paginiFriedman, Michael. Re-Evaluation Logical PositivismNelida GentileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derrida Negotiating The LegacyDocument203 paginiDerrida Negotiating The LegacyfadwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revista Transilvania 11-12 2013 BT PDFDocument152 paginiRevista Transilvania 11-12 2013 BT PDFRadu RadutoiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moulines - Suppes. A Profile PDFDocument10 paginiMoulines - Suppes. A Profile PDFBrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arthur 2Document18 paginiArthur 2朝崎 あーさーÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hintikka - Kant On The Mathematical MethodDocument25 paginiHintikka - Kant On The Mathematical MethodNicolás AldunateÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Music OntologyDocument5 paginiWhat Is The Music OntologyNegruta DumitruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salamucha1993 Article ComparisonsBetweenScholasticLo PDFDocument10 paginiSalamucha1993 Article ComparisonsBetweenScholasticLo PDFjohn galtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structure and Functions of The Title in LiteratureDocument29 paginiStructure and Functions of The Title in LiteratureMatheus MullerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Günther Patzig Aristotle's Theory of The Syllogism A Logico-Philological Study of Book A of The Prior Analytics Springer Netherlands (1968)Document231 paginiGünther Patzig Aristotle's Theory of The Syllogism A Logico-Philological Study of Book A of The Prior Analytics Springer Netherlands (1968)dobizoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ciencia de MoultonDocument2 paginiCiencia de MoultonGia OrionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Destiny & Control in Human SystemsDocument230 paginiDestiny & Control in Human SystemsgrandgazeboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review of Paolo Trovatos EverythingDocument11 paginiBook Review of Paolo Trovatos EverythingGyalten JigdrelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Unguru FowlerDocument11 paginiReview Unguru FowlerHumberto ClímacoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barker 1978 A Note On Republic 531C1-4. ArtDocument7 paginiBarker 1978 A Note On Republic 531C1-4. ArtSantiago Javier BUZZIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Humorous Texts A Semantic and PragmaticDocument6 paginiHumorous Texts A Semantic and PragmaticNatalia SzułowiczÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Johns Hopkins University Press New Literary HistoryDocument17 paginiThe Johns Hopkins University Press New Literary HistoryfrankÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gruner - The Concept of Speculative Philosophy of HistoryDocument19 paginiGruner - The Concept of Speculative Philosophy of HistoryIgnacio del PinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Did Plato Write Socratic DialoguesDocument17 paginiDid Plato Write Socratic DialoguesRod RigoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laird - Handbook of Literary RhetoricDocument3 paginiLaird - Handbook of Literary Rhetorica1765Încă nu există evaluări

- Additional History of LogicDocument18 paginiAdditional History of LogicStef C G Sia-ConÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filosofia CientificaDocument195 paginiFilosofia CientificaPwaqoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richard Hope Aristotle's Metaphysics Newly Translated As A Postscript To Natural Science Rees, D. A.Document1 paginăRichard Hope Aristotle's Metaphysics Newly Translated As A Postscript To Natural Science Rees, D. A.Cy PercutioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allee Rev Tubach Index Exemplorum JAF 1972Document4 paginiAllee Rev Tubach Index Exemplorum JAF 1972Elvis PreslieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Holger Thesleff - Platonic ChronologyDocument27 paginiHolger Thesleff - Platonic ChronologyM MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook of Mathematical Logic Ed. BarwDocument9 paginiHandbook of Mathematical Logic Ed. BarwlisserstroiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auerbach Curtius MLNDocument5 paginiAuerbach Curtius MLNbeltopoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Real AnalysisDocument459 paginiEssential Real AnalysisPranay Goswami100% (2)

- Selected Topics in Three-Dimensional Synthetic Projective Geometry-Introduction, References, and IndexDocument18 paginiSelected Topics in Three-Dimensional Synthetic Projective Geometry-Introduction, References, and IndexjohndimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green L. D., Aristotelean Rhetoric, Dialectic, and The Traditions of Antistrofos, Rhetorica" 8.1 (1990), S. 5-27.Document25 paginiGreen L. D., Aristotelean Rhetoric, Dialectic, and The Traditions of Antistrofos, Rhetorica" 8.1 (1990), S. 5-27.White201Încă nu există evaluări

- Lachterman - Klein's TrilogyDocument8 paginiLachterman - Klein's TrilogyDan Nad100% (1)

- Mirco A. Mannucci and Rose M. Cherubin - Model Theory of Ultrafinitism I: Fuzzy Initial Segments of ArithmeticDocument30 paginiMirco A. Mannucci and Rose M. Cherubin - Model Theory of Ultrafinitism I: Fuzzy Initial Segments of ArithmeticNine000Încă nu există evaluări

- Torstendahl R (2003) - Fact Truth and TextDocument28 paginiTorstendahl R (2003) - Fact Truth and TextAlexandra BejaranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Introduction A. J. GreimasDocument17 pagini3 Introduction A. J. GreimaschristinemzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Titusland,+25818 57123 1 CEDocument13 paginiTitusland,+25818 57123 1 CEAdelfo Manawataw Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Harris - Rhetoric of ScienceDocument27 paginiHarris - Rhetoric of ScienceNisa RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structure and Functions of The Title in Literature - GenetteDocument30 paginiStructure and Functions of The Title in Literature - GenetteRiddhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- How The Laws of Physics LieDocument3 paginiHow The Laws of Physics LieArlinda HendersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Treatise On ANALYTICAL DYNAMICS L. A. PARSDocument661 paginiA Treatise On ANALYTICAL DYNAMICS L. A. PARSWilliam VenegasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soames Book SymposiumDocument6 paginiSoames Book SymposiumSubhay kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plato's Forms, Pythagorean Mathematics, and StichometryDocument32 paginiPlato's Forms, Pythagorean Mathematics, and Stichometrytweakin100% (2)

- Cambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyDocument4 paginiCambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyCy PercutioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein, Plato, and The Historical SocratesDocument42 paginiWittgenstein, Plato, and The Historical SocratesAngela Marcela López RendónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barnes On GluckerDocument3 paginiBarnes On GluckerbrysonruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tkrause PDFDocument169 paginiTkrause PDFFrancisco Salto AlemanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematical Association of America The American Mathematical MonthlyDocument18 paginiMathematical Association of America The American Mathematical MonthlyNishant PandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tate Plato's Political PhilosophyDocument2 paginiTate Plato's Political PhilosophyCy PercutioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ueberweg, System of LogicDocument626 paginiUeberweg, System of LogicMerrim43100% (2)

- Introduction to Mathematical Thinking: The Formation of Concepts in Modern MathematicsDe la EverandIntroduction to Mathematical Thinking: The Formation of Concepts in Modern MathematicsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Genera Dicendi - Hendrickson, G. L. (1905)Document44 paginiGenera Dicendi - Hendrickson, G. L. (1905)glorydaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Semiotic VSrhetoricDocument23 paginiSemiotic VSrhetoriczagohuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asa Isuse - Asa As Vrea HBDDocument5 paginiAsa Isuse - Asa As Vrea HBDstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-North Carolina PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-North Carolina PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Benson, Ragnar - Breath of The DragonDocument15 paginiBenson, Ragnar - Breath of The DragonRap SrkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Rhode Island PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Rhode Island PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Ohio PDFDocument11 paginiBush Record-Ohio PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Pennsylvania PDFDocument11 paginiBush Record-Pennsylvania PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-South Carolina PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-South Carolina PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Oregon PDFDocument12 paginiBush Record-Oregon PDFAdeel AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-New Hampshire PDFDocument14 paginiBush Record-New Hampshire PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-North Dakota PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-North Dakota PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-New Mexico PDFDocument12 paginiBush Record-New Mexico PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Oklahoma PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Oklahoma PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-New Jersey PDFDocument6 paginiBush Record-New Jersey PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-New York PDFDocument6 paginiBush Record-New York PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Mississippi PDFDocument6 paginiBush Record-Mississippi PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Montana PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Montana PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Missouri PDFDocument12 paginiBush Record-Missouri PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Nevada PDFDocument11 paginiBush Record-Nevada PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Minnesota PDFDocument11 paginiBush Record-Minnesota PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Nebraska PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Nebraska PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Massachusetts PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Massachusetts PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Maryland PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Maryland PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Michigan PDFDocument12 paginiBush Record-Michigan PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Kentucky PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Kentucky PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Kansas PDFDocument6 paginiBush Record-Kansas PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Maine PDFDocument15 paginiBush Record-Maine PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Iowa PDFDocument15 paginiBush Record-Iowa PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Louisiana PDFDocument11 paginiBush Record-Louisiana PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Illinois PDFDocument6 paginiBush Record-Illinois PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Bush Record-Indiana PDFDocument5 paginiBush Record-Indiana PDFstefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- 2006 America's First Cold War ArmyDocument224 pagini2006 America's First Cold War ArmyBrendan MatsuyamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steven Paul Scher Music and Text Critical Inquiries 1992Document345 paginiSteven Paul Scher Music and Text Critical Inquiries 1992Marcia KaiserÎncă nu există evaluări

- GreeceDocument50 paginiGreeceAnonymous 28JsiJFa100% (1)

- F. R IN Phil History Mod 1 Week 3 and 4 - 2020-2021 PDFDocument5 paginiF. R IN Phil History Mod 1 Week 3 and 4 - 2020-2021 PDFShinTaxErrorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antelpe Wife EnotesDocument14 paginiAntelpe Wife EnotesNicoleta NicoletaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesDocument3 paginiExercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesNurhikma AristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- U.S. Marines in Vietnam Fighting The North Vietnamese 1967Document351 paginiU.S. Marines in Vietnam Fighting The North Vietnamese 1967Bob Andrepont100% (11)

- Islas de Los PintadosDocument8 paginiIslas de Los PintadosMaricel Alota Algo100% (1)

- Concepts of History: Petrus Jethro C. Leopoldo B6-3Document2 paginiConcepts of History: Petrus Jethro C. Leopoldo B6-3PETRUS JETHRO LEOPOLDOÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Per) Forming Archival ResearchDocument25 pagini(Per) Forming Archival ResearchMarwah Tiffani SyahriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University History Project WorkDocument13 paginiDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University History Project WorkALOK RAOÎncă nu există evaluări

- El Colapso de Copan Cameron McneilDocument6 paginiEl Colapso de Copan Cameron McneilB'alam DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

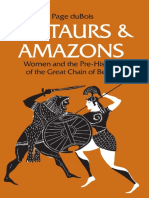

- (Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFDocument184 pagini(Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFMamutfenyo100% (4)

- The Youth Is The Hope of Our Future.: Lesson 1: Republic Act 1425Document24 paginiThe Youth Is The Hope of Our Future.: Lesson 1: Republic Act 1425Chris john MacatangayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading in The Phil. History 1st ChapterDocument16 paginiReading in The Phil. History 1st ChapterNicole Bongon FloranzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Controversies in Philippine HistoryDocument51 paginiControversies in Philippine HistoryJEVIN MAE PE�ARANDA100% (1)

- Mukharji - VishalyakaraniDocument24 paginiMukharji - Vishalyakarani\Încă nu există evaluări

- Buck-Morss, "Revolutionary Time"Document16 paginiBuck-Morss, "Revolutionary Time"nnc2109Încă nu există evaluări

- Hawk & Moor Trilogy - The Unoff - Kent David KellyDocument414 paginiHawk & Moor Trilogy - The Unoff - Kent David KellyMax KlostermannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gec 2Document1 paginăGec 2NorfaisahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome PDocument167 paginiBooks and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome PLance KirbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donald M StadtnerDocument24 paginiDonald M StadtnerhongnyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Town Planning-Module 1Document21 paginiTown Planning-Module 1shaheeda vk100% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To HistoryDocument5 paginiChapter 1 - Introduction To HistoryUmm SamiÎncă nu există evaluări