Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Legislative Inquiry and Oversight Function

Încărcat de

Loren SanapoDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Legislative Inquiry and Oversight Function

Încărcat de

Loren SanapoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

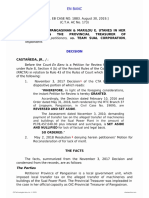

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

I.

BENGZON, JR. V. SENATE BLUE RIBBON COMMITTEE

KAPUNAN, J.:

The power of congress to conduct investigations in inherent in the legislative process.

That power is broad. it encompasses inquiries concerning the administration of existing

laws as well as proposed, or possibly needed statutes. It includes surveys of defects in

our social,economic, or political system for the purpose of enabling Congress to remedy

them. It comprehends probes into departments of the Federal Government to expose

corruption, inefficiency or waste. But broad asis this power ofinquiry, it is not unlimited.

There is no general authority to expose the private affairs ofindividuals without

justification in terms of the functions of congress.

Since congress may only investigate into those areas in which it may potentially

legislate or appropriate, it cannot inquire into matters which are within the exclusive

province of one of the other branches of the government. Lacking the judicial power

given to the Judiciary, it cannot inquire into mattes that are exclusively the concern of

the Judiciary. Neither can it suplant the Executive in what exclusively belongs to the

Executive.

FACTS:

In pursuance of a speech made by Senator Enrile during a priviledged hour asking the

Senate to look into the matter of the alleged acquisition of the Lopa Group of the properties of

Kokoy Romualdez which is a subject of sequestration by the PCG and citing probable violations

of Republic Act No. 3019 Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Section 5, petitioner Ricardo

Lopa and others were subpoenaed by the Committee to appear before it and testify on "what

they know" regarding the "sale of thirty-six (36) corporations belonging to Benjamin "Kokoy"

Romualdez."

, Ricardo Lopa declined to testify on the ground that his testimony may "unduly prejudice" the

defendants in Civil Case No. 0035 before the Sandiganbayan. Petitioner Jose F.S. Bengzon, Jr.

likewise refused to testify involing his constitutional right to due process, and averring that the

publicity generated by respondents Committee's inquiry could adversely affect his rights as well

as those of the other petitioners who are his co-defendants in Civil Case No. 0035 before the

Sandiganbayan.

Claiming that the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee is poised to subpoena them and required

their attendance and testimony in proceedings before the Committee, in excess of its jurisdiction

and legislative purpose, in clear and blatant disregard of their constitutional rights, and to their

grave and irreparable damager, prejudice and injury, and that there is no appeal nor any other

plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law, the petitioners filed the

present petition for prohibition with a prayer for temporary restraning order and/or injunctive

relief

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

In its comment, respondent Committee claims that this court cannot properly inquire into the

motives of the lawmakers in conducting legislative investigations, much less cna it enjoin the

Congress or any its regular and special commitees like what petitioners seek from making

inquiries in aid of legislation, under the doctrine of separation of powers, which obtaines in our

present system of government.

RULING:

The Supreme court granted the petition.

1. The Court has Jurisdiction

T he separation of powers is a fundamental principle in our system of government. It

obtains not hrough express provision but by actual division in our Constitution. Each

department of the government has exclusive cognizance of matters wihtin its

jurisdiction, and is supreme within its own sphere. But it does not follow from the fact

that the three powers are to be kept separate and distinct that the Constitution

intended them to be absolutely unrestrained and independent of each other. The

Constitution has provided for an elaborate system of checks and balances to secure

coordination in the workings of the various departments of the government...

But in the main, the Constitution has blocked out with deft strokes and in bold lines,

allotment of power to the executive, the legislative and the judicial departments of the

government. The ovelapping and interlacing of funcstions and duties between the

several deaprtments, however, sometimes makes it hard to say just where the

political excitement, the great landmarks of the Constitution are apt to be forgotten or

marred, if not entirely obliterated, in cases of conflict, the judicial departments is the

only constitutional organ which can be called upon to determine the proper allocation

of powers between the several departments and among the integral or constituent

units thereof.

The Constitution is a definition of the powers of government. Who is to determine

the nature, scope and extent of such powers? The Constitution itself has provided for

the instrumentality of the judiciary as the rational way. And when the judiciary

mediates to allocate constitutional boundaries; it does not assert any superiority over

the other departments; it does not inr eality nullify or invalidate an act of the

legislature, but only asserts the solemn and sacred obligation assigned to it by tyhe

Constitution to determine conflicting claims of authority under the Constitution and to

established for the parties in an actual controversy the rights which that instrument

secures and guarantess to them. This is in thruth all that is involved in what is termed

"judicial supremacy" which properly is the power of judicial review under the

Constitution. Even the, this power of judicial review is limited to actual cases and

controversies to be exercised after full opportunity of argument by the parties, and

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

limited further to the constitutional question raised or the very lis mota presented.

Any attempt at abstraction could only lead to dialectics and barren legal questions

and to sterile conclusions unrelated to actualities. Narrowed as its function is in this

manner, the judiciary does not pass upon questions of wisdom, justice or expediency

of legislation. More thatn that, courts accord the presumption of constitutionality to

legislative enactments, not only because the legislature is presumed to abide by the

Constitution but also becuase the judiciary in the determination of actual cases and

controversies must reflect the wisdom and justice of the people as expressed

through their representatives in the executive and legislative departments of the

government.

The Court is thus of the considered view that it has jurisdiction over the present

controversy for the purpose of determining the scope and extent of the power of the

Senate Blue Ribbon Committee to conduct inquiries into private affirs in purported

aid of legislation.

2. The Legislature has no power to inquire on the matter at issue.

A.

The committee investigation wanted by Senator Enrile is not in aid of a

legislation, The power to conduct formal inquiries or investigations in specifically

provided for in Sec. 1 of the Senate Rules of Procedure Governing Inquiries in

Aid of Legislation. Such inquiries may refer to the implementation or reexamination of any law or in connection with any proposed legislation or the

formulation of future legislation. They may also extend to any and all matters

vested by the Constitution in Congress and/or in the Seante alone.

the Senate may refer to any committee or committees any speech or resolution

filed by any Senator which in tis judgment requires an appropriate inquiry in aid of

legislation. In order therefore to ascertain the character or nature of an inquiry, resort

must be had to the speech or resolution under which such an inquiry is proposed to

be made.

Verily, the speech of Senator Enrile contained no suggestion of

contemplated legislation; he merely called upon the Senate to look into a possible

violation of Sec. 5 of RA No. 3019, otherwise known as "The Anti-Graft and

Corrupt Practices Act." I other words, the purpose of the inquiry to be conducted

by respondent Blue Ribbon commitee was to find out whether or not the relatives

of President Aquino, particularly Mr. ricardo Lopa, had violated the law in

connection with the alleged sale of the 36 or 39 corporations belonging to

Benjamin "Kokoy" Romualdez to the Lopaa Group. There appears to be,

therefore, no intended legislation involved.

The Court is also not impressed with the respondent Committee's

argument that the questioned inquiry is to be conducted pursuant to Senate

Resolution No. 212. The said resolution was introduced by Senator Jose D. Lina

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

in view of the representaions made by leaders of school youth, community groups

and youth of non-governmental organizations to the Senate Committee on Youth

and Sports Development, to look into the charges against the PCGG filed by three

(3) stockholders of Oriental petroleum, i.e., that it has adopted a "get-rich-quick

scheme" for its nominee-directors in a sequestered oil exploration firm.

the inquiry under Senate Resolution No. 212 is to look into the charges

against the PCGG filed by the three (3) stockholders of Oriental Petroleum in

connection with the implementation of Section 26, Article XVIII of the

Constitution.

It cannot, therefore, be said that the contemplated inquiry on the subject of

the privilege speech of Senator Juan Ponce Enrile, i.e., the alleged sale of the 36

(or 39) corporations belonging to Benjamin "Kokoy" Romualdez to the Lopa

Group is to be conducted pursuant to Senate Resolution No. 212 because, firstly,

Senator Enrile did not indict the PCGG, and, secondly, neither Mr. Ricardo Lopa

nor the herein petitioners are connected with the government but are private

citizens.

It appeals, therefore, that the contemplated inquiry by respondent

Committee is not really "in aid of legislation" becuase it is not related to a

purpose within the jurisdiction of Congress, since the aim of the investigation is to

find out whether or not the ralatives of the President or Mr. Ricardo Lopa had

violated Section 5 RA No. 3019, the "Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act", a

matter that appears more within the province of the courts rather than of the

legislature. Besides, the Court may take judicial notice that Mr. Ricardo Lopa died

during the pendency of this case

B.

It is violative of the separation of powers between the Senate or Congress and

that Judiciary. The pending civil case of the petitioners under Civil Case No. 0035

before the Sandiganbayan is where these issues by the Senate should be discussed.

It cannot be overlooked that when respondent Committee decide to conduct its

investigation of the petitioners, the complaint in Civil No. 0035 had already been filed

with the Sandiganbayan. A perusal of that complaint shows that one of its principal

causes of action against herein petitioners, as defendants therein, is the alleged sale

of the 36 (or 39) corporations belonging to Benjamin "Kokoy" Romualdez. Since the

issues in said complaint had long been joined by the filing of petitioner's respective

answers thereto, the issue sought to be investigated by the respondent Committee is

one over which jurisdiction had been acquired by the Sandiganbayan. In short, the

issue had been pre-empted by that court. To allow the respondent Committee to

conduct its own investigation of an issue already before the Sandiganbayan would not

only pose the possibility of conflicting judgments betweena legislative committee and

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

a judicial tribunal, but if the Committee's judgment were to be reached before that of

the Sandiganbayan, the possibility of its influence being made to bear on the ultimate

judgment of the Sandiganbayan can not be discounted.

In fine, for the rspondent Committee to probe and inquire into the same

justiciable controversy already before the Sandiganbayan, would be an

encroachment into the exclusive domain of judicial jurisdiction that had much earlier

set in.

II.

SENATE OF THE PHILIPINES V ERMITA

Executive privilege, whether asserted against Congress, the courts, or the public, is

recognized only in relation to certain types of information of a sensitive character. While

executive privilege is a constitutional concept, a claim thereof may be valid or not

depending on the ground invoked to justify it and the context in which it is made.

Noticeably absent is any recognition that executive officials are exempt from the duty to

disclose information by the mere fact of being executive officials. Indeed, the

extraordinary character of the exemptions indicates that the presumption inclines heavily

against executive secrecy and in favor of disclosure.

Facts:

This case is regarding the railway project of the North Luzon Railways

Corporation with the China National Machinery and Equipment Group as well as the

Wiretapping activity of the ISAFP, and the Fertilizer scam.

The Senate Committees sent invitations to various officials of the Executive Department

and AFP officials for them to appear before Senate on Sept. 29, 2005. Before said date

arrived, Executive Sec. Ermita sent a letter to Senate President Drilon, requesting for a

postponement of the hearing on Sept. 29 in order to afford said officials ample time and

opportunity to study and prepare for the various issues so that they may better enlighten

the Senate Committee on its investigation. Senate refused the request.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

On Sept. 28, 2005, the President issued EO 464, effective immediately, which, among

others, mandated that all heads of departments of the Executive Branch of the

government shall secure the consent of the President prior to appearing before either

House of Congress. Pursuant to this Order, Executive Sec. Ermita communicated to the

Senate that the executive and AFP officials would not be able to attend the meeting

since the President has not yet given her consent. Despite the lack of consent, Col.

Balutan and Brig. Gen. Gudani, among all the AFP officials invited, attended the

investigation. Both faced court marshal for such attendance.

petitioners, all claiming to have standing to file the suit because of the transcendental

importance of the issues they posed, pray, in their petition that E.O. 464 be declared null

and void for being unconstitutional; that respondent Executive Secretary Ermita, in his

capacity as Executive Secretary and alter-ego of President Arroyo, be prohibited from

imposing, and threatening to impose sanctions on officials who appear before Congress

due to congressional summons. Additionally, petitioners claim that E.O. 464 infringes on

their rights and impedes them from fulfilling their respective obligations.

Ruling:

To determine the constitutionality of E.O. 464, the Supreme Court discussed the two

different functions of the Legislature: The power to conduct inquiries in aid of legislation

and the power to conduct inquiry during question hour.

A. Question Hour:

The power to conduct inquiry during question hours is recognized in Article 6, Section 22

of the 1987 Constitution, which reads:

The heads of departments may, upon their own initiative, with the consent of the

President, or upon the request of either House, as the rules of each House shall provide,

appear before and be heard by such House on any matter pertaining to their

departments. Written questions shall be submitted to the President of the Senate or the

Speaker of the House of Representatives at least three days before their scheduled

appearance. Interpellations shall not be limited to written questions, but may cover

matters related thereto. When the security of the State or the public interest so requires

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

and the President so states in writing, the appearance shall be conducted in executive

session.

The objective of conducting a question hour is to obtain information in pursuit of

Congress oversight function. When Congress merely seeks to be informed on how

department heads are implementing the statutes which it had issued, the department

heads appearance is merely requested.

The Supreme Court construed Section 1 of E.O. 464 as those in relation to the

appearance of department heads during question hour as it explicitly referred to Section

22, Article 6 of the 1987 Constitution.

The requirement then to secure presidential consent under Section 1, limited as it is

only to appearances in the question hour, is valid on its face. For under Section 22,

Article VI of the Constitution, the appearance of department heads in the question hour

is discretionary on their part.

Section 1 cannot, however, be applied to appearances of department heads in inquiries

in aid of legislation. Congress is not bound in such instances to respect the refusal of the

department head to appear in such inquiry, unless a valid claim of privilege is

subsequently made, either by the President herself or by the Executive Secretary

B. In aid of Legislation:

The Legislatures power to conduct inquiry in aid of legislation is expressly recognized in

Article 6, section21 of the 1987 Constitution, which reads:

The Senate or the House of Representatives or any of its respective committees may

conduct inquiries in aid of legislation in accordance with its duly published rules of

procedure. The rights of persons appearing in, or affected by, such inquiries shall be

respected.

The power of inquiry in aid of legislation is inherent in the power to legislate. A legislative

body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the

conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change. And where the legislative

body does not itself possess the requisite information, recourse must be had to others

who do possess it.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

But even where the inquiry is in aid of legislation, there are still recognized exemptions

to the power of inquiry, which exemptions fall under the rubric of executive privilege.

This is the power of the government to withhold information from the public, the courts,

and the Congress. This is recognized only to certain types of information of a sensitive

character. When Congress exercise its power of inquiry, the only way for department

heads to exempt themselves therefrom is by a valid claim of privilege. They are not

exempt by the mere fact that they are department heads. Only one official may be

exempted from this power -- the President.

Section 2 & 3 of E.O. 464 requires that all the public officials enumerated in Section 2(b)

should secure the consent of the President prior to appearing before either house of

Congress. The enumeration is broad. In view thereof, whenever an official invokes

E.O.464 to justify the failure to be present, such invocation must be construed as a

declaration to Congress that the President, or a head of office authorized by the

President, has determined that the requested information is privileged.

The letter sent by the Executive Secretary to Senator Drilon does not explicitly invoke

executive privilege or that the matter on which these officials are being requested to be

resource persons falls under the recognized grounds of the privilege to justify their

absence. Nor does it expressly state that in view of the lack of consent from the

President under E.O. 464, they cannot attend the hearing. The letter assumes that the

invited official possesses information that is covered by the executive privilege. Certainly,

Congress has the right to know why the executive considers the requested information

privileged. It does not suffice to merely declare that the President, or an authorized head

of office, has determined that it is so.

The claim of privilege under Section 3 of E.O. 464 in relation to Section 2(b) is thus

invalid per se. It is not asserted. It is merely implied. Instead of providing precise and

certain reasons for the claim, it merely invokes E.O. 464, coupled with an announcement

that the President has not given her consent.

When an official is being summoned by Congress on a matter which, in his own

judgment, might be covered by executive privilege, he must be afforded reasonable time

to inform the President or the Executive Secretary of the possible need for invoking the

privilege. This is necessary to provide the President or the Executive Secretary with fair

opportunity to consider whether the matter indeed calls for a claim of executive privilege.

If, after the lapse of that reasonable time, neither the President nor the Executive

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

Secretary invokes the privilege, Congress is no longer bound to respect the failure of the

official to appear before Congress and may then opt to avail of the necessary legal

means to compel his appearance.

Wherefore, the petitions are partly granted. Sections 2(b) and 3 of E.O. 464 are declared

void. Section 1(a) are however valid.

III.

GAUDANI V. SENGA

It cannot be gainsaid that certain liberties of persons in the military service, including the

freedom of speech, may be circumscribed by rules of military discipline. Thus, to a certain

degree, individual rights may be curtailed, because the effectiveness of the military in fulfilling its

duties under the law depends to a large extent on the maintenance of discipline within its ranks.

Hence, lawful orders must be followed without question and rules must be faithfully complied

with, irrespective of a soldier's personal views on the matter.

FACTS:

The Senate invited Gen. Gudani and Lt. Col. Balutan to clarify allegations of 2004 election fraud

and the surfacing of the Hello Garci tapes. PGMA issued EO 464 enjoining officials of the

executive department including the military establishment from appearing in any legislative

inquiry without her consent. AFP Chief of Staff Gen. Senga issued a Memorandum, prohibiting

Gen. Gudani, Col. Balutan et al from appearing before the Senate Committee without

Presidential approval. However, the two appeared before the Senate in spite the fact that a

directive has been given to them. As a result, the two were relieved of their assignments for

allegedly violating the Articles of War and the time honoured principle of the Chain of

Command. Gen. Senga ordered them to be subjected before the General Court

Martial proceedings for willfuly violating an order of a superior officer.

RULING:

1. President has constitutional authority to issue an orde to the members of the AFP preventing

them from testifying before a legislative inquiry.

The commander-in-chief provision in the Constitution is denominated as Section 18,

Article VII, which begins with the simple declaration that [t]he President shall be the

Commander-in-Chief of all armed forces of the Philippines Outside explicit constitutional

limitations, such as those found in Section 5, Article XVI, the commander-in-chief clause vests

on the President, as commander-in-chief, absolute authority over the persons and actions of the

members of the armed forces. Such authority includes the ability of the President to restrict the

travel, movement and speech of military officers, activities which may otherwise be sanctioned

under civilian law.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

, by virtue of her power as commander-in-chief, and that as a consequence a military officer

who defies such injunction is liable under military justice.

Critical to military discipline is obeisance to the military chain of command. Willful disobedience

of a superior officer is punishable by court-martial under Article 65 of the Articles of War. [45] An

individual soldier is not free to ignore the lawful orders or duties assigned by his immediate

superiors. For there would be an end of all discipline if the seaman and marines on board a ship

of war [or soldiers deployed in the field], on a distant service, were permitted to

act upon their own opinion of their rights [or their opinion of the

Presidents intent], and to throw off the authority of the commander whenever they supposed it

to be unlawfully exercised.[46]

Further traditional restrictions on members of the armed forces are those imposed on free

speech and mobility. Kapunan is ample precedent in justifying that a soldier may be restrained

by a superior officer from speaking out on certain matters. As a general rule, the discretion of a

military officer to restrain the speech of a soldier under his/her command will be accorded

deference, with minimal regard if at all to the reason for such restraint. It is integral to military

discipline that the soldiers speech be with the consent and approval of the military commander.

The necessity of upholding the ability to restrain speech becomes even more imperative if the

soldier desires to speak freely on political matters. The Constitution requires that [t]he armed

forces shall be insulated from partisan politics, and that [n]o member of the military shall engage

directly or indirectly in any partisan political activity, except to vote. [47] Certainly, no constitutional

provision or military indoctrination will eliminate a soldiers ability to form a personal political

opinion, yet it is vital that such opinions be kept out of the public eye. For one, political belief is a

potential source of discord among people, and a military torn by political strife is incapable of

fulfilling its constitutional function as protectors of the people and of the State. For another, it is

ruinous to military discipline to foment an atmosphere that promotes an active dislike of or

dissent against the President, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Soldiers are

constitutionally obliged to obey a President they may dislike or distrust. This fundamental

principle averts the country from going the way of banana republics.

of equal importance, is the principle that mobility of travel is another necessary restriction on

members of the military. A soldier cannot leave his/her post without the consent of the

commanding officer. The reasons are self-evident. The commanding officer has to be aware at

all times of the location of the troops under command, so as to be able to appropriately respond

to any exigencies. For the same reason, commanding officers have to be able to restrict the

movement or travel of their soldiers, if in their judgment, their presence at place of call of duty is

necessary. At times, this may lead to unsentimental, painful consequences, such as a soldier

being denied permission to witness the birth of his first-born, or to attend the funeral of a parent.

Yet again, military life calls for considerable personal sacrifices during the period of conscription,

wherein the higher duty is not to self but to country.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

It is clear that the basic position of petitioners impinges on these fundamental principles we

have discussed. They seek to be exempted from military justice for having traveled to the

Senate to testify before the Senate Committee against the express orders of Gen. Senga, the

AFP Chief of Staff. If petitioners position is affirmed, a considerable exception would be carved

from the unimpeachable right of military officers to restrict the speech and movement of their

juniors. The ruinous consequences to the chain of command and military discipline simply

cannot warrant the Courts imprimatur on petitioners position.

2.Any chamber of Congress which seeks the appearance before it of a military officer against

the consent of the President has adequate remedies under law to compel such attendance.

Any military official whom Congress summons to testify before it may be compelled to do so by

the President. If the President is not so inclined, the President may be commanded by judicial

order to compel the attendance of the military officer. Final judicial orders have the force of the

law of the land which the President has the duty to faithfully execute.

SC ruled in Senate v. Ermita that the President may not issue a blanket

requirement of prior consent on executive officials summoned by the

legislature to attend a congressional hearing.

In doing so, the Court recognized the considerable limitations on executive privilege,

and affirmed that the privilege must be formally invoked on specified grounds.

However, the ability of the President to prevent military officers from testifying before

Congress does not turn on executive privilege, but on the Chief Executives power as

commander-in-chief to control the actions and speech of members of the armed

forces. The Presidents prerogatives as commander-in-chief are not hampered by the

same limitations as in executive privilege.

At the same time, the refusal of the President to allow members of the military to

appear before Congress is still subject to judicial relief. The Constitution itself

recognizes as one of the legislatures functions is the conduct of inquiries in aid of

legislation. Inasmuch as it is ill-advised for Congress to interfere with the Presidents

power as commander-in-chief, it is similarly detrimental for the President to unduly

interfere with Congresss right to conduct legislative inquiries. The impasse did not

come to pass in this petition, since petitioners testified anyway despite the

presidential prohibition. Yet the Court is aware that with its pronouncement today that

the President has the right to require prior consent from members of the armed

forces, the clash may soon loom or actualize.

The duty falls on the shoulders of the President, as commander-in-chief, to authorize

the appearance of the military officers before Congress. Even if the President has

earlier disagreed with the notion of officers appearing before the legislature to

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

testify, the Chief Executive is nonetheless obliged to comply with the final orders of

the courts.

IV.

NERI V. SENATE COMMITTEE ON ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS

Executive privilege is not a personal privilege, but one that adheres to the Office of the

President. It exists to protect public interest, not to benefit a particular public official. Its purpose,

among others, is to assure that the nation will receive the benefit of candid, objective and

untrammeled communication and exchange of information between the President and his/her

advisers in the process of shaping or forming policies and arriving at decisions in the exercise of

the functions of the Presidency under the Constitution. The confidentiality of the Presidents

conversations and correspondence is not unique. It is akin to the confidentiality of judicial

deliberations. It possesses the same value as the right to privacy of all citizens and more,

because it is dictated by public interest and the constitutionally ordained separation of

governmental powers.

FACTS:

petitioner appeared before respondent Committees and testified for about eleven (11) hours on

matters concerning the National Broadband Project (the "NBN Project"), a project awarded by

the Department of Transportation and Communications ("DOTC") to Zhong Xing

Telecommunications Equipment ("ZTE"). Petitioner disclosed that then Commission on

Elections ("COMELEC") Chairman Benjamin Abalos offered him P200 Million in exchange for

his approval of the NBN Project. He further narrated that he informed President Gloria

Macapagal Arroyo ("President Arroyo") of the bribery attempt and that she instructed him not to

accept the bribe. However, when probed further on President Arroyo and petitioners

discussions relating to the NBN Project, petitioner refused to answer, invoking "executive

privilege." To be specific, petitioner refused to answer questions on: (a) whether or not President

Arroyo followed up the NBN Project,4 (b) whether or not she directed him to prioritize it,5 and (c)

whether or not she directed him to approve it.6

Respondent Committees persisted in knowing petitioners answers to these three questions by

requiring him to appear and testify once more on November 20, 2007. On November 15, 2007,

Executive Secretary Eduardo R. Ermita wrote to respondent Committees and requested them to

dispense with petitioners testimony on the ground of executive privilege.

petitioner did not appear before respondent Committees upon orders of the President invoking

executive privilege. On November 22, 2007, the respondent Committees issued the show-cause

letter requiring him to explain why he should not be cited in contempt. On November 29, 2007,

in petitioners reply to respondent Committees, he manifested that it was not his intention to

ignore the Senate hearing and that he thought the only remaining questions were those he

claimed to be covered by executive privilege.

RULING:

1.

YES. There is a presidential communications privilege.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

In Almonte v. Chavez, Chavez v. Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG),

and Chavez v. PEA, the Court articulated in these cases that "there are certain types of

information which the government may withhold from the public, " that there is a "governmental

privilege against public disclosure with respect to state secrets regarding military, diplomatic and

other national security matters"; and that "the right to information does not extend to matters

recognized as privileged information under the separation of powers, by which the Court meant

Presidential conversations, correspondences, and discussions in closed-door Cabinet

meetings."

In light of this highly exceptional nature of the privilege, the Court finds it essential to limit to the

President the power to invoke the privilege. She may of course authorize the Executive

Secretary to invoke the privilege on her behalf, in which case the Executive Secretary must

state that the authority is "By order of the President", which means that he personally consulted

with her. The privilege being an extraordinary power, it must be wielded only by the highest

official in the executive hierarchy. In other words, the President may not authorize her

subordinates to exercise such power. There is even less reason to uphold such authorization in

the instant case where the authorization is not explicit but by mere silence. Section 3, in relation

to Section 2(b), is further invalid on this score.

In this case, it was the President herself, through Executive Secretary Ermita, who invoked

executive privilege on a specific matter involving an executive agreement between the

Philippines and China, which was the subject of the three (3) questions propounded to petitioner

Neri in the course of the Senate Committees investigation. Thus, the factual setting of this case

markedly differs from that passed upon in Senate v. Ermita.

if what is involved is the presumptive privilege of presidential communications when invoked by

the President on a matter clearly within the domain of the Executive, the said presumption

dictates that the same be recognized and be given preference or priority, in the absence of proof

of a compelling or critical need for disclosure by the one assailing such presumption. Any

construction to the contrary will render meaningless the presumption accorded by settled

jurisprudence in favor of executive privilege.

2. YES. The three (3) questions are covered by executive privilege

A. Respondent Committees contend that the power to secure a foreign loan does not relate to a

"quintessential and non-delegable presidential power," because the Constitution does not vest it

in the President alone, but also in the Monetary Board which is required to give its prior

concurrence and to report to Congress.

This argument is unpersuasive.

The fact that a power is subject to the concurrence of another entity does not make such power

less executive. "Quintessential" is defined as the most perfect embodiment of something, the

concentrated essence of substance.24 On the other hand, "non-delegable" means that a power

or duty cannot be delegated to another or, even if delegated, the responsibility remains with the

obligor.25 The power to enter into an executive agreement is in essence an executive power.

This authority of the President to enter into executive agreements without the concurrence of

the Legislature has traditionally been recognized in Philippine jurisprudence

The "doctrine of operational proximity" was laid down precisely to limit the scope of the

presidential communications privilege but, in any case, it is not conclusive. In the case at bar,

the danger of expanding the privilege "to a large swath of the executive branch" (a fear

apparently entertained by respondents) is absent because the official involved here is a member

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

of the Cabinet, thus, properly within the term "advisor" of the President; in fact, her alter ego and

a member of her official family.

"operational proximity" was laid down in In re: Sealed Case27precisely to limit the scope of the

presidential communications privilege.

In that case it was stated that not every person who plays a role in the development of

presidential advice, no matter how remote and removed from the President, can qualify for the

privilege. In particular, the privilege should not extend to staff outside the White House in

executive branch agencies. Instead, the privilege should apply only to communications authored

or solicited and received by those members of an immediate White House advisors staff who

have broad and significant responsibility for investigation and formulating the advice to be given

the President on the particular matter to which the communications relate.

Claim of executive privilege is not merely founded on her generalized interest in confidentiality.

The Letter dated November 15, 2007 of Executive Secretary Ermita specified presidential

communications privilege in relation to diplomatic and economic relations with another

sovereign nation as the bases for the claim.

The context in which executive privilege is being invoked is that the information sought to be

disclosed might impair our diplomatic as well as economic relations with the Peoples Republic

of China. Given the confidential nature in which this information were conveyed to the President,

he cannot provide the Committee any further details of these conversations, without disclosing

the very thing the privilege is designed to protect.

In upholding executive privilege with respect to three (3) specific questions, it did not in any way

curb the publics right to information or diminish the importance of public accountability and

transparency.

This Court did not rule that the Senate has no power to investigate the NBN Project in aid of

legislation. There is nothing in the assailed Decision that prohibits respondent Committees from

inquiring into the NBN Project. They could continue the investigation and even call petitioner

Neri to testify again. He himself has repeatedly expressed his willingness to do so. Our Decision

merely excludes from the scope of respondents investigation the three (3) questions that elicit

answers covered by executive privilege and rules that petitioner cannot be compelled to appear

before respondents to answer the said questions. We have discussed the reasons why these

answers are covered by executive privilege. That there is a recognized public interest in the

confidentiality of such information is a recognized principle in other democratic States. To put it

simply, the right to information is not an absolute right.

3.

NO. The three (3) questions are not critical to the Legislatures function.

In the case at bar, we are not confronted with a courts need for facts in order to adjudge liability

in a criminal case but rather with the Senates need for information in relation to its legislative

functions. This leads us to consider once again just how critical is the subject information in the

discharge of respondent Committees functions. The burden to show this is on the respondent

Committees, since they seek to intrude into the sphere of competence of the President in order

to gather information which, according to said respondents, would "aid" them in crafting

legislation.

Anent the function to curb graft and corruption, it must be stressed that respondent Committees

need for information in the exercise of this function is not as compelling as in instances when

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

the purpose of the inquiry is legislative in nature. This is because curbing graft and corruption is

merely an oversight function of Congress. And if this is the primary objective of respondent

Committees in asking the three (3) questions covered by privilege, it may even contradict their

claim that their purpose is legislative in nature and not oversight. In any event, whether or not

investigating graft and corruption is a legislative or oversight function of Congress, respondent

Committees investigation cannot transgress bounds set by the Constitution.

Congress is neither a law enforcement nor a trial agency. Moreover, it bears stressing that no

inquiry is an end in itself; it must be related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the

Congress, i.e. legislation. Investigations conducted solely to gather incriminatory evidence and

"punish" those investigated are indefensible. There is no Congressional power to expose for the

sake of exposure.

5.

YES. The Senate committed grave abuse of discretion in issuing the contempt order.

The deliberation of the respondent Committees that led to the issuance of the contempt order is

flawed. Instead of being submitted to a full debate by all the members of the respondent

Committees, the contempt order was prepared and thereafter presented to the other members

for signing. As a result, the contempt order which was issued on January 30, 2008 was not a

faithful representation of the proceedings that took place on said date. Records clearly show

that not all of those who signed the contempt order were present during the January 30, 2008

deliberation when the matter was taken up.

SEPARATE CONCURRING OPINION

BRION, J.

First Point: Constitutional Rights of Romulo Neri

The 1987 Constitution that expressly provides that The rights of persons appearing in or

affected by such inquiries shall be respected. Interestingly, this Section as a whole seeks to

strengthen the hand of the Legislature in the exercise of inquiries in aid of legislation. In so

doing, however, it makes the above reservation for the individual who may be at the receiving

end of legislative might. What these rights are the Section does not expressly say, but these

rights are recognized by jurisprudence and cannot be other than those provided under the Bill of

Rights the constitutional provisions that level the individuals playing field as against the

government and its inherent and express powers.

Thus, Neri cannot be deprived of his liberty without due process of law, as provided under

Article III Section 1 of the Bill of Rights. Short of actual denial of liberty, Neri should as a

matter of constitutional right likewise be protected from the humiliation that he so feared in a

congressional investigation.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

Neri did comply with the Senates orders to attend and testify; underwent hours of grilling before

the Senate Committees; did submit explanations for the times when he could not comply; and

committed to attend future hearings on matters that are not privileged. To further ensure that he

is properly guided, Neri sought judicial intervention by recourse to this Court through the present

petition.

In more ways than one, the rights of petitioner Neri the individual were grossly violated by

Senate action in contravention of the constitutional guarantee for respect of individual rights in

inquiries in aid of legislation.

Second Point: On Executive Privilege

It is not necessary for the conversation or correspondence to contain diplomatic, trade or

military secret as these matters are covered by their own reasons for confidential treatment.

What is material or critical is the fact of conversation or correspondence in the course of official

policy or decision making; privilege is recognized to afford the President and her executives the

widest latitude in terms of freedom from present and future embarrassment in their discussions

of policies and decisions.

Unless and until it can therefore be shown in the proper proceeding that the Presidential

conversation related to her involvement in, knowledge of or complicity in a crime, or where the

inquiry occurs in the setting of official law enforcement or prosecution, then the mantle of

privilege must remain so that disclosure cannot be compelled. This conclusion is dictated by

the requirement of order in the delineation of boundaries and allocation of governmental

responsibilities.

The proper proceeding is not necessarily in an inquiry in aid of legislation since the purpose of

bringing crime to light is served in proceedings before the proper police, prosecutory or judicial

body, not in the halls of congress in the course of investigating the effects of or the need for

current or future legislation.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

V.

GARCILLANO V HOUSE OF REP.

Section 21 of Article VI of the Constitution, requiring that the inquiry be in

accordance with the "duly published rules of procedure." We quote the OSGs

explanation:The phrase "duly published rules of procedure" requires the Senate

of every Congress to publish its rules of procedure governing inquiries in aid of

legislation because every Senate is distinct from the one before it or after it. Since

Senatorial elections are held every three (3) years for one-half of the Senates

membership, the composition of the Senate also changes by the end of each term.

Each Senate may thus enact a different set of rules as it may deem fit. Not having

published its Rules of Procedure, the subject hearings in aid of legislation

conducted by the 14th Senate, are therefore, procedurally infirm.

FACTS;

Case involves two Petition for Prohibition with Prayer for the Issuance of a Temporary

Restraining Order filed becore the court by petitioners (a) Garciliano and (b) Santiago

Ranada and Oswaldo Agcaoili, retired justices of the Court of Appeals.

Garcillano implores from the Court, as aforementioned, the issuance of an

injunctive writ to prohibit the respondent House Committees from playing the tape

recordings and from including the same in their committee report. He likewise prays that

the said tapes be stricken off the records of the House proceedings.While, petitioners

Santiago Ranada and Oswaldo Agcaoil They argued in the main that the intended

legislative inquiry violates R.A. No. 4200 and Section 3, Article III of the Constitution

since there is no proer publication.

RULING.

1. The court dismissed Garcilianos petition for being moot and academic

The Court notes that the recordings were already played in the House and heard

by its members.39 There is also the widely publicized fact that the committee reports

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

on the "Hello Garci" inquiry were completed and submitted to the House in plenary

by the respondent committees.40 Having been overtaken by these events, the

Garcillano petition has to be dismissed for being moot and academic. After all,

prohibition is a preventive remedy to restrain the doing of an act about to be done,

and not intended to provide a remedy for an act already accomplished.

2. The court ruled in favour of Ranada and Agcaoili.

.

Senate or the House of Representatives, or any of its respective committees may

conduct inquiries in aid of legislation in accordance with its duly published rules of procedure."

The requisite of publication of the rules is intended to satisfy the basic requirements of due

process.42 Publication is indeed imperative, for it will be the height of injustice to punish or

otherwise burden a citizen for the transgression of a law or rule of which he had no notice

whatsoever, not even a constructive one.43 What constitutes publication is set forth in Article 2 of

the Civil Code, which provides that "[l]aws shall take effect after 15 days following the

completion of their publication either in the Official Gazette, or in a newspaper of general

circulation in the Philippines."44

The respondents in G.R. No. 179275 admit in their pleadings and even on oral argument that

the Senate Rules of Procedure Governing Inquiries in Aid of Legislation had been published in

newspapers of general circulation only in 1995 and in 2006.45 With respect to the present

Senate of the 14th Congress, however, of which the term of half of its members commenced on

June 30, 2007, no effort was undertaken for the publication of these rules when they first

opened their session.

VI.

ROMERO II v ESTRADA

FACTS:

Petitioners Romero II and other members of the Board of Directors of R-II Builders, Inc.,

were invited on an investigation with regards to the investment of Overseas Workers Welfare

Administration (OWWA) funds in the Smokey Mountain project. The said investigation will aid

the Senate in determining possible amendments of Republic Act 8042 other known as the

Migrant Workers Act.

RULING :

NOT A SUB JUDICE

A. NO MORE ACTUAL CASE OR CONTROVERSY

The sub judice rule restricts comments and disclosures pertaining to judicial

proceedings to avoid prejudging the issue, influencing the court, or obstructing the

administration of justice. A violation of the sub judice rule may render one liable for

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

indirect contempt under Sec. 3(d), Rule 71 of the Rules of Court. [11] The rationale for

the rule adverted to is set out in Nestle Philippines v. Sanchez:

[I]t is a traditional conviction of civilized society everywhere that courts and

juries, in the decision of issues of fact and law should be immune from every

extraneous influence; that facts should be decided upon evidence produced

in court; and that the determination of such facts should be uninfluenced by

bias, prejudice or sympathies.[12]

Chavez, assuming for argument that it involves issues subject of the

respondent Committees assailed investigation, is no longer sub judice or

before a court or judge for consideration.[13] For by an en banc Resolution

dated July 1, 2008, the Court, in G.R. No. 164527, denied with finality the

motion of Chavez, as the petitioner in Chavez, for reconsideration of the

Decision of the Court dated August 15, 2007. In fine, it will not avail

petitioners any to invoke the sub judice effect of Chavez and resist, on that

ground, the assailed congressional invitations and subpoenas.

B. assuming hypothetically that Chavez is still pending final adjudication by

the Court, still, such circumstance would not bar the continuance of the

committee investigation.

in Sabio v. Gordon suggests as much:

The same directors and officers contend that the Senate is barred from

inquiring into the same issues being litigated before the Court of Appeals

and the Sandiganbayan. Suffice it to state that the Senate Rules of

Procedure Governing Inquiries in Aid of Legislation provide that the filing or

pendency of any prosecution or administrative action should not stop or

abate any inquiry to carry out a legislative purpose.[16]

A legislative investigation in aid of legislation and court proceedings has

different purposes. On one hand, courts conduct hearings or like

adjudicative procedures to settle, through the application of a law, actual

controversies arising between adverse litigants and involving demandable

rights. On the other hand, inquiries in aid of legislation are, inter alia,

undertaken as tools to enable the legislative body to gather information and,

thus, legislate wisely and effectively; [17] and to determine whether there is a

need to improve existing laws or enact new or remedial legislation, [18] albeit

the inquiry need not result in any potential legislation. On-going judicial

proceedings do not preclude congressional hearings in aid of legislation.

While Sabio and Standard Chartered Bank advert only to pending criminal and

administrative cases before lower courts as not posing a bar to the continuation of a legislative

inquiry, there is no rhyme or reason that these cases doctrinal pronouncement and their

rationale cannot be extended to appealed cases and special civil actions awaiting final

disposition before this Court.

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

C. Moot and Acaademic

all pending matters and proceedings, i.e., unpassed bills

and even legislative investigations, of the Senate of a particular

Congress are considered terminated upon the expiration of that

Congress and it is merely optional on the Senate of the succeeding

Congress to take up such unfinished matters, not in the same status,

but as if presented for the first time.

The denial of the instant recourse is still indicated for another compelling

reason. As may be noted, PS Resolution Nos. 537 and 543 were passed

in 2006 and the letter-invitations and subpoenas directing the petitioners

to appear and testify in connection with the twin resolutions were sent

out in the month of August 2006 or in the past Congress. On the

postulate that the Senate of each Congress acts separately and

independently of the Senate before and after it, the aforesaid invitations

and subpoenas are considered functos oficio and the related legislative

inquiry conducted is, for all intents and purposes, terminated.

VII.

GARCIA V MATA (Under Presidential Veto and Congressional Override)

Ewan ko asan yung veto ditto.

Eusebio Garcia was a reserve officer on active duty with the Armed

Forces of the Philippines until his reversion to inactive status on 15 November

1960, pursuant to the provisions of Republic Act No. 2332. At the time of

reversion, Petitioner held the rank of Captain. Petitioner's reversion to inactive

status was pursuant to the provisions of Republic Act 2334, and such reversion

was neither for cause, at his own request, nor after court-martial

proceedings;From 15 November 1960 up to the present, petitioner has been on

inactive status and as such, he has neither received any emoluments from the

Armed Forces of the Philippines, nor was he ever employed in the Government

in any capacity; As a consequence of his reversion to inactive status, petitioner

filed the necessary petitions with the offices of the AFP Chief of Staff, the

Secretary of National Defense, and the President, respectively, but received reply

only from the Chief of Staff through the AFP Adjutant General.

Thus,he brought an action for "Mandamus and Recovery of a Sum of Money" in

the court a quo to compel the respondents Secretary of National Defense and

Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines 2 to reinstate him in the

active commissioned service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, to readjust

his rank, and to pay all the emoluments and allowances due to him from the time

of his reversion to inactive status. The trial court dismissed the petition. The court

ruled that paragraph 11 of the "Special Provisions for the Armed Forces of the

Philippines" in Republic Act 1600 is "invalid, unconstitutional and inoperative."

POLITICAL LAW REVIEW 2016

a.LEGISLATIVE INQUIRY AND OVERSIGHT FUNCTION

HELD:

R. A 1660 is UNCONSTITUTIONAL: Case dismissed.

1. The insertion of a non-appropriation item in an appropriation

measure is unconstitutional.A perusal of the challenged provision of

R.A. 1600 fails to disclose its relevance or relation to any appropriation

item therein, or to the Appropriation Act as a whole. From the very first

clause of paragraph 11 itself, which reads, After the approval of this Act,

and when there is no emergency, no reserve officer of the Armed Forces

of the Philippines may be called to a tour of active duty for more than two

years during any period of five consecutive years: the incongruity and

irrelevancy are already evident. While R.A. 1600 appropriated money for

the operation of the Government for the fiscal year 1956-1957, the said

paragraph 11 refers to the fundamental governmental policy matters of

the calling to active duty and the .reversion to inactive status of reserve

officers in the AFP. The incongruity and irrelevancy continue throughout

the entire paragraph.

2. A provision in a statute which is not fairly included in the subject

expressed in the title thereof or is not germane to or properly connected

with the subject is unconstitutional and null and void.The subject of

R.A. 1600, as expressed in its title, is restricted to appropriating funds

for the operation of the government. Any provision contained in the body

of the act that is fairly included in this restricted subject or any matter

properly connected therewith is valid and operative. But, if a provision in

the body of the act is not fairly included in this restricted subject, like the

provision relating to the policy matters of calling to active duty and

reversion to inactive duty of reserve officers of the AFP, such provision is

inoperative and of no effect.

3. A void provision of an appropriation statute confers no right and

affords no protection.Upon the foregoing dissertation, we declare

Paragraph 11 of the SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR THE ARMED

FORCES OF THE PHILIPPINES as unconstitutional, invalid and

inoperative. Being unconstitutional, it confers no right and affords no

protection. In legal contemplation it is as though it has never been

passed.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- LSG ConstitutionDocument22 paginiLSG ConstitutionRailla PunoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tobias v. Abalos, 239 SCRA 106Document4 paginiTobias v. Abalos, 239 SCRA 106zatarra_12Încă nu există evaluări

- Debate Federalism (New 2)Document3 paginiDebate Federalism (New 2)PhantasiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- WRITTEN REPORT in Local Government and RegionalDocument5 paginiWRITTEN REPORT in Local Government and RegionalRONEL GALELAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz BeeDocument6 paginiQuiz BeeKersey BadocdocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4. Fiscal AutonomyDocument7 paginiChapter 4. Fiscal AutonomyElla TriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pesca vs. Pesca, G.R. No. 136921. April 17, 2001Document3 paginiPesca vs. Pesca, G.R. No. 136921. April 17, 2001Mark Rainer Yongis LozaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- 62 Tocao V CADocument2 pagini62 Tocao V CANichole LanuzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IR003 SAMAL 2 Midterm - 2 PDFDocument16 paginiIR003 SAMAL 2 Midterm - 2 PDFJocelyn Mae CabreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Local Government AdministrationDocument56 paginiLocal Government AdministrationAnirtsÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Prisoner's Dilemma?Document4 paginiWhat Is The Prisoner's Dilemma?Mihaela VădeanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic V LacapDocument16 paginiRepublic V LacapJennefer Angolluan100% (1)

- Postponement of Barangay and SK ElectionsDocument3 paginiPostponement of Barangay and SK ElectionsRonaldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engendering Development:: An Overview of The Philippine ExperienceDocument26 paginiEngendering Development:: An Overview of The Philippine ExperienceYieMaghirang100% (1)

- Mactan Cebu International Airport Authority Vs MarcosDocument17 paginiMactan Cebu International Airport Authority Vs MarcosMp CasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alfredo Long, Joseph Lim, Liu Yek See v. Lydia Basa, Anthony Sayheeliam and Yao ChekDocument1 paginăAlfredo Long, Joseph Lim, Liu Yek See v. Lydia Basa, Anthony Sayheeliam and Yao ChekAbi ContinuadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti Case Digest (Fundamental Powers of The State)Document28 paginiConsti Case Digest (Fundamental Powers of The State)Vhe CostanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critical Review of Public Participation Legal Framework Initiatives at National and County Level 19.07.2021Document26 paginiA Critical Review of Public Participation Legal Framework Initiatives at National and County Level 19.07.2021Brian MutieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surigao Electric Co., Inc. vs. Municipality of Surigao, 24 SCRA 898Document4 paginiSurigao Electric Co., Inc. vs. Municipality of Surigao, 24 SCRA 898Marchini Sandro Cañizares KongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Police Power DigestsDocument12 paginiPolice Power Digestsgem_mataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Separation of Powers Case DigestDocument13 paginiSeparation of Powers Case DigestAna EstacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problems in Bureaucratic SupplyDocument4 paginiProblems in Bureaucratic Supplyatt_doz86100% (1)

- Gender Equality Policy GuidelinesDocument27 paginiGender Equality Policy GuidelinesRAHUL LALJIBHAI PANCHOLI-IBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legislative Concurrence On TreatiesDocument19 paginiLegislative Concurrence On TreatiesCristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation 1Document32 paginiPresentation 1Hiei TriggerÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-63915Document10 paginiG.R. No. L-63915Julian DubaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charter Change: Unitary To Federalism: in Partial Fulfilment For The Requirement in Legal ResearchDocument17 paginiCharter Change: Unitary To Federalism: in Partial Fulfilment For The Requirement in Legal ResearchJacel Anne DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magtajas v. Pryce PropertiesDocument25 paginiMagtajas v. Pryce Propertieskeith alanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- L. Acebedo Optical Vs CA. GR No. 100152. (March 31, 2000)Document4 paginiL. Acebedo Optical Vs CA. GR No. 100152. (March 31, 2000)Hechelle S. DE LA CRUZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mpa 609 Reaction PapersDocument16 paginiMpa 609 Reaction PapersClemen John TualaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boracay Foundation v. AklanDocument55 paginiBoracay Foundation v. AklanElwell MarianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PA 200 Public Value SystemDocument26 paginiPA 200 Public Value SystemAbbie Garcia Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Loc Goc Comp2Document31 paginiLoc Goc Comp2Fernando BayadÎncă nu există evaluări

- CREATION and DISSOLUTION OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONSDocument62 paginiCREATION and DISSOLUTION OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONSNica PineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tondo Medical Center Employees Association v. Court of Appeals PDFDocument35 paginiTondo Medical Center Employees Association v. Court of Appeals PDFSamanthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. Ragay PDFDocument10 paginiPeople vs. Ragay PDFFatzie MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tañada VS CuencoDocument1 paginăTañada VS CuencoRochedale ColasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Local Government in GhanaDocument10 paginiLocal Government in Ghanaelliot_sarpong6483Încă nu există evaluări

- Local Autonomy Cases FullDocument65 paginiLocal Autonomy Cases FullJamiah Obillo HulipasÎncă nu există evaluări

- COA DoctrineDocument4 paginiCOA DoctrineCzarPaguioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Television ViolenceDocument8 paginiImpact of Television Violenceombudslady100% (1)

- Final Legal ResearchDocument22 paginiFinal Legal ResearchIyleÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 6735 - The Initiative and Referendum ActDocument8 paginiRA 6735 - The Initiative and Referendum ActRocky MarcianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay On The Management TheoryDocument12 paginiEssay On The Management Theorycmn88100% (1)

- Ceniza vs. ComelecDocument3 paginiCeniza vs. ComelecRaymondÎncă nu există evaluări

- Villar vs. Tech Institute 135 Scra 706Document11 paginiVillar vs. Tech Institute 135 Scra 706Juris SyebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mallion vs. AlcantaraDocument1 paginăMallion vs. AlcantaraJ Rachelle PaezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Facts: Erap Is Under Prosecution Under RA 7080 (Plunder Law) As Amended by RA 7659. He Denies The Constitutionality ofDocument6 paginiFacts: Erap Is Under Prosecution Under RA 7080 (Plunder Law) As Amended by RA 7659. He Denies The Constitutionality ofJohn CheekyÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEC Vs Interport Resources CorpDocument16 paginiSEC Vs Interport Resources CorpDee WhyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Galing Pook Awards 2018 Application FormDocument5 paginiGaling Pook Awards 2018 Application FormEnrico_LariosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art X Local GovernmentDocument3 paginiArt X Local GovernmentJoseEdgarNolascoLucesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Features of Local Governments Finish ProductDocument19 paginiFeatures of Local Governments Finish Productcarlos MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exit EssayDocument3 paginiExit Essayapi-249961689Încă nu există evaluări

- Article XIII Social Justice and Human Rights PDFDocument23 paginiArticle XIII Social Justice and Human Rights PDFApple Jean Dominguez ArcillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paid Menstrual LeaveDocument1 paginăPaid Menstrual LeaveIshpreet KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charter Change ArticleDocument12 paginiCharter Change ArticleAj GuanzonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Executive Order No. 47Document6 paginiExecutive Order No. 47Iris Rivera-PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maria Carolina P. Araullo Et. AlDocument3 paginiMaria Carolina P. Araullo Et. AlClaire SilvestreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Term Paper-Foundation of EducDocument11 paginiTerm Paper-Foundation of EducRonald Abrasaldo SatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art 6. Bengzon Vs Blue Ribbon Case DigestDocument3 paginiArt 6. Bengzon Vs Blue Ribbon Case DigestCharlotte Jennifer AspacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIR RULING NO. 171-81: Sycip, Gorres, Velayo & Co. MR B V Abela Tax DivisionDocument4 paginiBIR RULING NO. 171-81: Sycip, Gorres, Velayo & Co. MR B V Abela Tax DivisionLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lists of Requirements From Taxpayers For20220713-12-Xaao9tDocument8 paginiLists of Requirements From Taxpayers For20220713-12-Xaao9tLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Separation GuidelinesDocument25 paginiBusiness Separation GuidelinesLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- HB 02014Document12 paginiHB 02014Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dof Opinion: CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021Document2 paginiDof Opinion: CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 218880-2018-Revenue Office Tax Exemption Manual TESLite20221008-12-1h3k0fuDocument71 pagini218880-2018-Revenue Office Tax Exemption Manual TESLite20221008-12-1h3k0fuLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- For+Posting+Notice+0948 2022+ORDER+ +ERC+Case+No.+2019 081+RC+ (Consolidated+With+DO) + (HVB+SGD)Document56 paginiFor+Posting+Notice+0948 2022+ORDER+ +ERC+Case+No.+2019 081+RC+ (Consolidated+With+DO) + (HVB+SGD)Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 259697-2019-Power Sector Assets Liabilities Management20220413-11-1j9trrDocument4 pagini259697-2019-Power Sector Assets Liabilities Management20220413-11-1j9trrLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- C.T.a. EB Case No. 1883 (C.T.a. AC No. 173) - Province of Pangasinan v. Team Sual Corp. - 236817-2019-Province - of - Pangasinan - v. - Team - Sual - Corp.Document15 paginiC.T.a. EB Case No. 1883 (C.T.a. AC No. 173) - Province of Pangasinan v. Team Sual Corp. - 236817-2019-Province - of - Pangasinan - v. - Team - Sual - Corp.Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 51106-2015-Makati v. Trans-Asia Power Generation Corp.20210505-12-14orvnrDocument3 pagini51106-2015-Makati v. Trans-Asia Power Generation Corp.20210505-12-14orvnrLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 141115-1972-Davao Light Power Co. Inc. v. Commissioner20210505-11-146967nDocument6 pagini141115-1972-Davao Light Power Co. Inc. v. Commissioner20210505-11-146967nLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extrajudicial Settlement of Estate TemplateDocument4 paginiExtrajudicial Settlement of Estate Templateblue13_fairy100% (1)

- 2021 Suwa - Shipyard - Machineries - Corp.20211108 12 MkhgioDocument4 pagini2021 Suwa - Shipyard - Machineries - Corp.20211108 12 MkhgioLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40581-2015-National Power Corp. v. Tenorio20210505-13-3tjqjhDocument17 pagini40581-2015-National Power Corp. v. Tenorio20210505-13-3tjqjhLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sec-Ogc Opinion No. 14-10: Sebastian Liganor Galinato & AlamisDocument4 paginiSec-Ogc Opinion No. 14-10: Sebastian Liganor Galinato & AlamisFrances EsteronÎncă nu există evaluări

- dc2021 09 0029Document65 paginidc2021 09 0029Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jao No 2008 1Document28 paginiJao No 2008 1Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIR Ruling No. 001-89 - Proposed Donations of The Shares of Stock - 4916-1989-Proposed - Donations - of - The - Shares - of - Stock20210505-12-LmqzzrDocument2 paginiBIR Ruling No. 001-89 - Proposed Donations of The Shares of Stock - 4916-1989-Proposed - Donations - of - The - Shares - of - Stock20210505-12-LmqzzrLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEC Opinion - Mr. Fernando C. Santico - 178279-1991-Mr. - Fernando - C. - Santico20210623-11-9s3w53Document2 paginiSEC Opinion - Mr. Fernando C. Santico - 178279-1991-Mr. - Fernando - C. - Santico20210623-11-9s3w53Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 136222-1984-Manila Wine Merchants Inc. v. CommissionerDocument12 pagini136222-1984-Manila Wine Merchants Inc. v. CommissionerAstina85Încă nu există evaluări

- Trans-Philippines Investment CorporationDocument2 paginiTrans-Philippines Investment CorporationLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asedillo Ramos AssociatesDocument2 paginiAsedillo Ramos AssociatesLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sycip Salazar Hernandez GatmaitanDocument3 paginiSycip Salazar Hernandez GatmaitanLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reacquiring Shares of Stocks Transferred To BIR - 50164-1992-Reacquiring - Shares - of - Stocks - Transferred - To20210505-11-Nd5agqDocument3 paginiReacquiring Shares of Stocks Transferred To BIR - 50164-1992-Reacquiring - Shares - of - Stocks - Transferred - To20210505-11-Nd5agqLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Philippine Acetylene Co.: BIR RULING NO. 159-59Document1 paginăThe Philippine Acetylene Co.: BIR RULING NO. 159-59Loren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updated Wuhan Coronavirus Infographic 270120 Eng PDFDocument1 paginăUpdated Wuhan Coronavirus Infographic 270120 Eng PDFvicki 99Încă nu există evaluări

- RR 18 2012Document5 paginiRR 18 2012JA LogsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exit Interview TemplateDocument3 paginiExit Interview TemplateNiharikaYadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advisory On Masks Infographic Final 250120 Eng PDFDocument1 paginăAdvisory On Masks Infographic Final 250120 Eng PDFLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spa - LorenDocument3 paginiSpa - LorenLoren SanapoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kemper B52453 2017 07 25Document157 paginiKemper B52453 2017 07 25Laura StylesÎncă nu există evaluări

- President EngDocument88 paginiPresident Engapi-3734665Încă nu există evaluări

- Grade 11 Entreprenuership Module 1Document24 paginiGrade 11 Entreprenuership Module 1raymart fajiculayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamic Finance On BNPL - The Opportunity AheadDocument14 paginiIslamic Finance On BNPL - The Opportunity AheadFaiz ArchitectsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Docket - Larson v. Perry (Dorland) ("Bad Art Friend")Document20 paginiCivil Docket - Larson v. Perry (Dorland) ("Bad Art Friend")x2478Încă nu există evaluări

- Green v. Speedy InterrogatoriesDocument5 paginiGreen v. Speedy Interrogatoriessamijiries100% (2)

- Kant 9 ThesisDocument6 paginiKant 9 ThesisMary Montoya100% (1)

- Basis of Institutional Capacity Building of Rural-Local Government in Bangladesh: A Brief DiscussionDocument9 paginiBasis of Institutional Capacity Building of Rural-Local Government in Bangladesh: A Brief DiscussionA R ShuvoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiotherapy License Exams Preparatory CDDocument1 paginăPhysiotherapy License Exams Preparatory CDeins_mpt33% (3)

- تاريخ بيروت واخبار الامراء البحتريين من الغرب PDFDocument341 paginiتاريخ بيروت واخبار الامراء البحتريين من الغرب PDFmjd1988111100% (1)

- Republic Vs OrtigasDocument2 paginiRepublic Vs OrtigasJan Kristelle BarlaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- China Banking Corporation Vs CIRDocument3 paginiChina Banking Corporation Vs CIRMiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review - An Undocumented Wonder - The Great Indian ElectionsDocument18 paginiBook Review - An Undocumented Wonder - The Great Indian Electionsvanshika.22bap9539Încă nu există evaluări

- Ethics of Ethical HackingDocument3 paginiEthics of Ethical HackingnellutlaramyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discover Aes MsdsDocument17 paginiDiscover Aes MsdsAkbar WildanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilbert Eugene Proffitt v. United States Parole Commission, 846 F.2d 73, 4th Cir. (1988)Document1 paginăWilbert Eugene Proffitt v. United States Parole Commission, 846 F.2d 73, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Paper G.K.Document20 paginiSample Paper G.K.9sz9rbdhzhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extending Criminal LiabilityDocument14 paginiExtending Criminal LiabilitymaustroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal English Vocabulary (English-German)Document6 paginiLegal English Vocabulary (English-German)MMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tremblay v. OpenAIDocument17 paginiTremblay v. OpenAITHRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aurbach VS Sanitary Wares CorpDocument3 paginiAurbach VS Sanitary Wares CorpDoll AlontoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writ HK NarulaDocument24 paginiWrit HK NarulasagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is A Forward Contract?Document3 paginiWhat Is A Forward Contract?Prateek SehgalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Cases 2nd AssignmentDocument141 paginiLabor Cases 2nd AssignmentMaria Janina100% (1)

- Kumari Bank Internship ReportDocument54 paginiKumari Bank Internship ReportBhatta GAutam69% (16)

- Constitution of India - SyllabusDocument1 paginăConstitution of India - SyllabusDavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peoria County Inmates 12/20/12Document6 paginiPeoria County Inmates 12/20/12Journal Star police documentsÎncă nu există evaluări