Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Aronite Thinking-"The Sarasvati Was More Sacred Than Ganga" Says Michel Danino The French Historian

Încărcat de

Aron Aronite0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

168 vizualizări11 paginiThe lost River of Sarasvathi, of the Vedic Rishis, should have been more sacred than the Ganges, for the Harrapan Hindu civilisation - says Michel Danino the French historian and 'lover all things Indian- especially her rich spirituality.

Titlu original

Aronite thinking-"The Sarasvati Was More Sacred Than Ganga" says Michel Danino the French historian

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThe lost River of Sarasvathi, of the Vedic Rishis, should have been more sacred than the Ganges, for the Harrapan Hindu civilisation - says Michel Danino the French historian and 'lover all things Indian- especially her rich spirituality.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

168 vizualizări11 paginiAronite Thinking-"The Sarasvati Was More Sacred Than Ganga" Says Michel Danino The French Historian

Încărcat de

Aron AroniteThe lost River of Sarasvathi, of the Vedic Rishis, should have been more sacred than the Ganges, for the Harrapan Hindu civilisation - says Michel Danino the French historian and 'lover all things Indian- especially her rich spirituality.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 11

'The Sarasvati was more sacred

than Ganga'

Declares Michel Danino- the French Scholar and

famous historian, in this interview to Vaihayasi Pande

Daniel, who loves all things India, especially her

Spirituality.

The Ganges and below- a detailed mapping of the now

lost Sarasvathi river.

At the edge of the Shola forest, at the foot of the

Ayyasamy Hills, in western Tamil Nadu, near

Coimbatore, lives a writer and scholar who traveled to

India [ Images ] from northern France [ Images ] over

three decades ago and never went home.

Michel Danino, who 'loves chapattis, sambar, yoga

and everything Indian', has devoted his life to studying

Indian culture/heritage and history, authoring several

books both in French and English on India.

Danino, who hails from a Jewish family who migrated

from Morocco to France, has had a life-long fascination

with India's ancient wisdom, marveling at the ageless

traditions that have kept its civilization alive and

relevant centuries later, like for instance the special

status accorded to nature… 'Since the start of the

Judeo-Christian tradition, the West broke away from

Nature and began regarding her as so much inanimate

matter to be exploited (a polite word for plunder). The

contrast with the ancient Indian attitude is as stark as

could be. Indian tradition regards the earth as a

goddess, Bhudevi', he says in Sri Aurobindo and Indian

Civilization.

His books examine key Indian historical issues or

wrestle with the cultural concerns present-day India

faces. The Invasion That Never Was (1996) looks at the

theories about the arrival/existence of the Aryans while

The Indian Mind Then and Now(2000), Is Indian Culture

Obsolete? are more sociological studies.

His latest book, The Lost River: On the Trail of the

Sarasvati (2010) focuses on the importance of this once

key river and its connection with Vedic culture and

Harappan civilizations. In addition to writing, teaching

and lecturing, Danino tellsVaihayasi Pande Daniel, he is

interested in conserving nature and was able to

jumpstart a movement to protect the Shola forest he

lives by the side of.

Why did you decide to live in India?

I was born and brought up in France. On the surface,

everything around me was fine: my family was a happy

one, my studies went well, and so on.

But I felt something essentially lacking in what life, as it

was organized there, had to offer, despite an

undeniably rich French culture. When I was 15 or so, I

stumbled on literature related to Indian spirituality, and

instantly felt that there was something that held

essential keys. I read several of the great masters,

something of India's ancient literature, and finally

decided that Sri Aurobindo's view of life and the world

was what I was looking for. It was not a passing craze

or a 'New Age' fad; it not only satisfied the intellect but

also touched the core of the being.

I came to India when I was just 21, after four years of

higher scientific studies. I stayed at Auroville for a few

years, then lived in the Nilgiris for over two decades,

and I have now been settled near Coimbatore for seven

years.

Throughout, my central purpose remained the same: to

study and practise the tools of self-discovery that India

has worked out over ages, and also to explore the roots

and beginnings of Indian civilization.

Tell us about your relationship with India. What are the

positives? And the negatives/disappointments? And

how do you describe India to folks back home?

Well, 'home' is India… and I gave up trying to describe

it long ago! Western societies, in comparison, seem to

me paper-thin. Here, the endless layering and

complexity are mind-boggling. I have always lived in

rural parts of south India, not in the cities — which I find

maddening — and everyday get reminded that this is

not a "nation" in the modern sense of the term — many

Western nations are recent and artificial creations —

but a civilization with millennial roots.

The 'positives' are obvious to me: A great degree of

cultural integration, clearly the result of a centuries-old

process, an unrivalled respect for cultural difference

and spiritual freedom, a sense of the divine presence in

the creation, all of which results in a generally fine

human substance.

As for the 'negatives', I am afraid they are all too

conspicuous: almost every Indian I meet knows that the

country's progress is hampered by an antediluvian

political class and administration that lack vision and

competence and promote a culture of spinelessness

and mediocrity; by a stinking, all-pervasive corruption

which the average Indian is reluctant or unable to fight;

by a lack of civic conscience and by a debilitating

educational system that takes pride in producing

brainless machines. Some of these millstones around

India's neck have a colonial legacy, but there is no

point blaming the British when we have had six

decades to rebuild the nation.

What is the Indian archaeology scene like? Is there

good work happening? Is good work getting enough

support?

A lot of good work is taking place in Indian archaeology,

most of it silently. You will get to know about it only if

you attend conferences or read specialized journals and

books. From Palaeolithic to medieval or even colonial

times, hundreds of sites are explored across the

country at any given time.

Yet there is undeniably a huge scope for improvement:

state-of-the-art methods are rarely available, some

artefacts or bone remains are misplaced or forgotten,

dating methods are applied scantily, reports are often

written late or not at all, few sites are adequately

protected after excavation, good museums are rare,

funds are inadequate, etc — in a word, a lot of precious

data is wasted or lost.

The field is crying for modernization, including a closer

collaboration with India's leading scientific institutions.

This is urgent, because unexcavated sites are

disappearing every day: in the Gangetic plains, for

instance, agriculture, exploding cities and

'development' are permanently blocking access to

more and more potentially rich sites. Much of our

ancient history is getting erased even before we get to

know it. We need far more effective heritage policies.

How did you get interested in the course of the

Sarasvati?

Studying India's roots soon takes you to the Indus or

Harappan civilization. As I explained in my book, from

1941 onward, Harappan sites were discovered -- by

Marc Aurel Stein to begin with -- along the dry bed of a

river locally called Ghaggar-Hakra. It so happens that

since the mid-nineteenth century, this river had been

identified with the Vedic Sarasvati: matching the Rig-

Veda's descriptions, it is located between the Yamuna

and the Sutlej, could be traced 'from the mountain to

the sea', and a small 'Sarsuti' or Sarasvati still exists in

its upper reaches (in Haryana).

Then comes the big question: If the Ghaggar-Hakra was

indeed the Sarasvati river — and the scholarly

consensus says it was — where do we find traces of a

Vedic culture in its basin? Paradoxically, the Harappan

culture, which is conventionally regarded as 'pre-Vedic',

is the dominant culture of the region while the

Sarasvati was flowing. These are some of the questions

I have tried to explore, of course building on the work

of many scholars.

Your interest in the Sarasvati as a foreigner must have

opened a lot of doors in India given its mythological

importance.

Technically, I am not a 'foreigner': I adopted Indian

citizenship some years ago. But you are right that

many Indians are often intrigued by my interest in the

Indus civilization, the lost Sarasvatî, and the origins of

Indian culture. They often react by saying that I am

'more Indian than Indians', which is rather flattering…

But after a while, the skin's colour makes no difference.

In the course of my many lectures — especially in

institutions of higher learning, such as IITs, universities,

etc —

I have found a considerable level of interest in these

questions. Naturally enough: they are intimately linked

to questions of origin and identity that resonate deeply

in many Indians. Yet, with a few brilliant exceptions,

there is a great dearth of material accessible to the

layman, who is often confused by not-so-genuine

literature; I thought I would try and help bridge the gap.

Any reason why Sarasvati is not considered as sacred

as Ganga?

As long as it flowed, the Sarasvati was more sacred

than Ganga, not less. In the Rig-Veda, Ganga is

mentioned twice in passing and given no importance

whatsoever, while of all the rivers mentioned, Sarasvati

alone is deified.

Paradoxically, the goddess seems to grow in stature as

the river dried up in stages; that is what the later

literature reflects. At the same time, many of

Sarasvati's attributes were transferred to Ganga, so

that in classical times, Ganga had gained in

prominence — naturally enough, since it was also the

lifeline of the new civilization.

Today, ironically, we cannot rule out a Sarasvati-like

end to the Gangetic rivers. The difference is that if it

happens, it will be a man-made tragedy.

You have spoken/written earlier about the

value/importance of Hindu wisdom especially in

connection with nature.

The old Indian attitude towards nature — not just Hindu

but also Buddhist, Jain, and of course tribal — is to

regard her as sacred: the creation, Bhudevi, is divine,

without any dichotomy with the creator: 'Heaven is my

father; my mother is this vast earth,' says the Rig-Veda.

The universe is compared to a thousand-branched tree

or sometimes to a cow (hence, for instance, the

symbolism of Krishna and the cows).

This attitude found itself reflected in rituals associated

with trees, wells or tanks: planting a tree or digging a

well or a pond were activities regarded as highly

meritorious even on the religious level, as many

inscriptions confirm. Historically, we findAshoka's edicts

prohibiting hunting and cruelty to animals, or Kautilya

prescribing the maintenance of wildlife sanctuaries.

Indians also excelled at water harvesting, right from

Harappan times — see Dholavira's colossal reservoirs

and network of drains.

But while some communities — take the Bishnois of

Rajasthan [ Images ] or the Todas of Tamil Nadu — are

famous for their spiritual bond with nature, the average

Hindu has lost it. He may worship a tree at a temple,

but will not mind deforestation at his doorstep; he will

travel to a distant pilgrimage spot but will litter it with

plastic bags and other garbage, and he will be

generally unaware of the all-round environmental

degradation his children are bound to inherit from him.

I also have found many 'educated' Indians scared at the

very thought of entering a forest. It is hard to account

for this deep disconnect in the Hindu psyche.

Do you feel India is losing touch with her epics even as

the rest of the world is very slowly realizing their value?

I don't feel that India is losing touch with the Ramayana

[ Images ] or the Mahabharata [ Images ]. See how

popular the television serials were a few years ago: the

country virtually ground to a halt during their

broadcast.

What is neglected is the epics' educational potential:

for centuries, in the simplest but the most effective

way, they taught Indians the nuances of dharma.

Today, with the mistaken belief that dharma means

religion, we have excluded it from our uninspiring

education, and of course from public life, while it was,

in many ways, the one ideal placed in front of all

sections of the society.

If you follow dharma, as a ruler you will work for lasting

improvements, especially for the weaker sections of the

society, rather than distribute sops to people while

robbing them; as a citizen, you will put up a fight

against injustice or corruption; as a teacher you will try

to enlighten the minds of your students rather than

stultify them. And so forth.

I do not wish to oversimplify things and romantically

suggest that all will be tiptop if we read and preach the

epics; I only mean that every country and society needs

some cultural values as guides. The values projected in

the epics are certainly time-tested, and they are more

profound than our superficial and rootless

'humanitarian' values.

Didn't the British do a better job of tracking India's

history, tradition and culture than Indians are doing

today? The best work on India is probably still authored

by Westerners.

I don't think so. There is much excellent work produced

in India, but it doesn't always receive the exposure it

deserves.

True, some Western archaeologists scholars have

contributed a lot of great value, especially those who

have had a genuine interest in India. Others have been

swayed by biases or the colonial baggage of

stereotypes. The British, as you say, did produce much

valuable material, but also implanted into the minds,

including Indian minds, a lot of disparaging notions that

still litter our textbooks. And even today, we find a few

rare but vociferous scholars indulging in outright

demonization of Indian culture.

I have been strongly opposed to the hollow kind of

glorification of ancient India that is too often seen in

India. It is historically untenable and does not help

towards an intelligent understanding of those times. No

society can be perfect and we should allow the

evidence to speak for itself as objectively as possible.

Ironically, today's Indology is founded on the unstated

diktat that you can be an Indologist only if you are an

outsider. This leads to many absurd and often abusive

misinterpretations and misrepresentations.

I am convinced that whatever your erudition may be,

you can study ancient India profitably only if you have

some empathy with the fundamentals of Indian culture.

In the end, however, I am not personally keen on an

opposition Western vs India. Some Westerners have

been perfectly at home with things Indian, while some

Indians look like perfect aliens. Let us refrain from cut-

and-dried formulas. If India still has something to offer

to the world, its culture will live.

Interview courtesy

-Vaihayasi Pande Daniel

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Remembering My Indic Heritage: Personal RecollectionsDe la EverandRemembering My Indic Heritage: Personal RecollectionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recent Findings On Indian Civilization - Michel DaninoDocument18 paginiRecent Findings On Indian Civilization - Michel DaninoMichel Danino100% (2)

- The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the GangesDe la EverandThe Twice-Born: Life and Death on the GangesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (6)

- None but India (Bharat) the Cradle of Aryans, Sanskrit, Vedas, & Swastika: Aryan Invasion of India’ and ‘Ie Family of Languages’Re-Examined and RebuttedDe la EverandNone but India (Bharat) the Cradle of Aryans, Sanskrit, Vedas, & Swastika: Aryan Invasion of India’ and ‘Ie Family of Languages’Re-Examined and RebuttedÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Indus to Independence: A Trek Through Indian History (Vol III The Disintegration of Empires)De la EverandFrom Indus to Independence: A Trek Through Indian History (Vol III The Disintegration of Empires)Încă nu există evaluări

- History of India from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century B.C.De la EverandHistory of India from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century B.C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Dhyansky 1987 Indus Origin YogaDocument21 paginiDhyansky 1987 Indus Origin Yogaalastier100% (1)

- Sanskrit Literature and The Scientific Development in IndiaDocument13 paginiSanskrit Literature and The Scientific Development in IndiaPramothThangarajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dhyanksy IndusValleyOriginYogaPractice PDFDocument21 paginiDhyanksy IndusValleyOriginYogaPractice PDFkellybrandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Allotropy: A Study Through Some Indian English NovelsDe la EverandCultural Allotropy: A Study Through Some Indian English NovelsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015.187993.the Dravidian Element in Indian Culture - Text PDFDocument189 pagini2015.187993.the Dravidian Element in Indian Culture - Text PDFsamsivam1955Încă nu există evaluări

- Revisiting History of IndiaDocument20 paginiRevisiting History of Indiaအသွ်င္ ေကသရÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASIABOOK Asian Quote Guide Book with 1000 useful proverbs, quotations and thoughtful insightsDe la EverandASIABOOK Asian Quote Guide Book with 1000 useful proverbs, quotations and thoughtful insightsEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- Syllabus - Indian Traditions, Cultural and Society (Knc-502/602)Document8 paginiSyllabus - Indian Traditions, Cultural and Society (Knc-502/602)CricTalkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Papers On Indian CultureDocument5 paginiResearch Papers On Indian Culturegvzexnzh100% (1)

- Indian Cultural Diplomacy: Celebrating Pluralism in a Globalised WorldDe la EverandIndian Cultural Diplomacy: Celebrating Pluralism in a Globalised WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review - Michel Danino. - I - The Lost River - On The Trail of THDocument8 paginiBook Review - Michel Danino. - I - The Lost River - On The Trail of THPadmaja BhogadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medieval Mysticism of IndiaDocument208 paginiMedieval Mysticism of IndiaPremanathan SambandamÎncă nu există evaluări

- India's Self Denial - by Francois Gautier - Archaeology OnlineDocument12 paginiIndia's Self Denial - by Francois Gautier - Archaeology Onlineravi0001Încă nu există evaluări

- Rabindranath TagoreDocument4 paginiRabindranath Tagoresree_431696931Încă nu există evaluări

- India'S Self Denial PrologueDocument21 paginiIndia'S Self Denial Prologueram_krishna70Încă nu există evaluări

- Multiculturalism and Identity Politics: A Study of Three Parsee Diasporic Writers Sidhwa, Mistry and DesaiDe la EverandMulticulturalism and Identity Politics: A Study of Three Parsee Diasporic Writers Sidhwa, Mistry and DesaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 3 - Ancient India (160 KB) ComDocument26 paginiLesson 3 - Ancient India (160 KB) ComTarun SrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indentity of SanthalsDocument16 paginiIndentity of SanthalsDebanand TuduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faults and Improvements in Vedic CultureDocument10 paginiFaults and Improvements in Vedic CultureRahul Vikram PathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Search of Paradise: A Saga of Courage, Resilience and ResistanceDe la EverandIn Search of Paradise: A Saga of Courage, Resilience and ResistanceÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Research Paper Topics in IndiaDocument12 paginiHistory Research Paper Topics in Indiatug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Discovery of Ancient India: Course Code: 313 Btech Final Year Course Instructor: Dr. A. Suneetha RajeshamDocument10 paginiDiscovery of Ancient India: Course Code: 313 Btech Final Year Course Instructor: Dr. A. Suneetha RajeshamSONY DEEKSHITHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Indian Literature 1994-Jul-Aug Vol. 37 Iss. 4 (162) ) Ramanujan - WHO NEEDS FOLKLORE - Ramanujan On FolkloreDocument15 pagini(Indian Literature 1994-Jul-Aug Vol. 37 Iss. 4 (162) ) Ramanujan - WHO NEEDS FOLKLORE - Ramanujan On FolkloreBernadett SmidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Culture Term PaperDocument7 paginiIndian Culture Term Paperafmzywxfelvqoj100% (1)

- Ganesha Goes to Lunch: Classics From Mystic IndiaDe la EverandGanesha Goes to Lunch: Classics From Mystic IndiaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (6)

- The Notion of Indianness: An Elucidation: Ashok VohraDocument10 paginiThe Notion of Indianness: An Elucidation: Ashok VohraSadman Shaid SaadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medieval Mysticism of India PDFDocument208 paginiMedieval Mysticism of India PDFRupa AbdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vytautas Narvilas Distant Yet Very Close Mintis Publisher 1989Document204 paginiVytautas Narvilas Distant Yet Very Close Mintis Publisher 1989mariusnarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Culture and TraditionsDocument10 paginiIndian Culture and TraditionsGanesh50% (2)

- Ashish NandyDocument6 paginiAshish NandysherwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memory Braids and Sari Texts: Weaving Migration JourneysDe la EverandMemory Braids and Sari Texts: Weaving Migration JourneysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aryavarta - Original Habitat of AryasDocument113 paginiAryavarta - Original Habitat of AryasKeshava Arya100% (1)

- Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five ContinentsDe la EverandLeaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five ContinentsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (9)

- Medieval Mystic IsDocument248 paginiMedieval Mystic Isadext50% (2)

- A Survey of Veerashaiva Religion and LiteratureDe la EverandA Survey of Veerashaiva Religion and LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDFDocument136 paginiPDFOnlineGatha The Endless TaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Holy Himalaya - The Religion Traditions and Scenery of A Himalayan Province Kumaon and Garhwal by ES Oakley (1905) PDFDocument356 paginiHoly Himalaya - The Religion Traditions and Scenery of A Himalayan Province Kumaon and Garhwal by ES Oakley (1905) PDFmorefaya2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Dhyanksy IndusValleyOriginYogaPracticeDocument21 paginiDhyanksy IndusValleyOriginYogaPracticeCharlie Higgins100% (1)

- Akhil Katyal - Three StoriesDocument10 paginiAkhil Katyal - Three StorieshikariisetsuyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jihad Storm and Fire From Afghanistan Coming To Kashmir and Sweep India - AronDocument11 paginiJihad Storm and Fire From Afghanistan Coming To Kashmir and Sweep India - AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partition of Iraq - AronDocument11 paginiPartition of Iraq - AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angela Merkelism - RULE OF DHIMMITUDE AND ISLAMIST ALLIANCE AS GOVERNMENTDocument10 paginiAngela Merkelism - RULE OF DHIMMITUDE AND ISLAMIST ALLIANCE AS GOVERNMENTAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reigious Extremism and Liberal Political FanaticismDocument18 paginiReigious Extremism and Liberal Political FanaticismAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPM-A TERRORIST ORGANISATION WITH A FAÇADE OF DEMOCRATIC PARTY AronDocument7 paginiCPM-A TERRORIST ORGANISATION WITH A FAÇADE OF DEMOCRATIC PARTY AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defeating Londonisation of India-AronDocument12 paginiDefeating Londonisation of India-AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Double Speak On ConversionsDocument9 paginiThe Double Speak On ConversionsAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Comparison of Netanyahu and Narender Modi United Nations SpeechDocument13 paginiCritical Comparison of Netanyahu and Narender Modi United Nations SpeechAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenyan Mall Attack and The Genius of Joseph Goebbels - AronDocument36 paginiKenyan Mall Attack and The Genius of Joseph Goebbels - AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Temptations of Messiah Modi by The Secular Devil in The Desert - AronDocument18 paginiTemptations of Messiah Modi by The Secular Devil in The Desert - AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHASING CHIMERAS - The Dangerous Mime of Tamil Separatist Rhetoric AronDocument15 paginiCHASING CHIMERAS - The Dangerous Mime of Tamil Separatist Rhetoric AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frédéric Bastiat - A HOMAGE TO " ..THE TRUTH "Document40 paginiFrédéric Bastiat - A HOMAGE TO " ..THE TRUTH "Aron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Keys of Anubis - AronDocument7 paginiThe Keys of Anubis - AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Progress Has Stalled ? DR Babu SuseelanDocument5 paginiWhy Progress Has Stalled ? DR Babu SuseelanAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- குழந்தைப் படுகொலைகள் Liberation Propoganda of LTTE and Some questions all failed to askDocument17 paginiகுழந்தைப் படுகொலைகள் Liberation Propoganda of LTTE and Some questions all failed to askAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaddafi's Guru - How LSE Became Libyan School of Economics For Socialist New World OrderDocument24 paginiGaddafi's Guru - How LSE Became Libyan School of Economics For Socialist New World OrderAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark Side of The Moon - The Game Behind Alleged Lankan War Crimes-Part 2Document11 paginiDark Side of The Moon - The Game Behind Alleged Lankan War Crimes-Part 2Aron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Great Vedic Women in Recent Times by Stephen KnappDocument13 paginiGreat Vedic Women in Recent Times by Stephen KnappAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Behind The Vandals of Osmania Jungle UniversityDocument4 paginiWhat Is Behind The Vandals of Osmania Jungle UniversityAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark Side of The Moon-The Game Behind Alleged Lankan War Crimes 1Document10 paginiDark Side of The Moon-The Game Behind Alleged Lankan War Crimes 1Aron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why All Religions Are Not The SameDocument6 paginiWhy All Religions Are Not The SameAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stone Walling The Wal-Marts - Subversion of Hindu Economic IdealsDocument15 paginiStone Walling The Wal-Marts - Subversion of Hindu Economic IdealsAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Storm Clouds From Pseudo Secularists DR Babu Suseelan and AronDocument15 paginiStorm Clouds From Pseudo Secularists DR Babu Suseelan and AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hunger Games (Film Review) The Fitna of The Free Markets AronDocument3 paginiHunger Games (Film Review) The Fitna of The Free Markets AronAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- GETTING INDIA RIGHT - DR Babu Suseelan's Speech To Indian American Intellectual ForumDocument4 paginiGETTING INDIA RIGHT - DR Babu Suseelan's Speech To Indian American Intellectual ForumAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindu RashtraDocument6 paginiHindu RashtraAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lal Bahadhur Shastri - A Leader Par Excellence by Brigadier Chit Ranjan Sawant VSMDocument10 paginiLal Bahadhur Shastri - A Leader Par Excellence by Brigadier Chit Ranjan Sawant VSMAron Aronite100% (1)

- Putting Hinduism On The American Cultural MapDocument13 paginiPutting Hinduism On The American Cultural MapAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gandhi-The Fetish of Sadomasochist Death Cult of Non-ViolenceDocument16 paginiGandhi-The Fetish of Sadomasochist Death Cult of Non-ViolenceAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Looking Back at Ultra Leftist Trail of TerrorDocument7 paginiLooking Back at Ultra Leftist Trail of TerrorAron AroniteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dekker V Weida Amicus Brief by 17 AGsDocument35 paginiDekker V Weida Amicus Brief by 17 AGsSarah WeaverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matrix CPP CombineDocument14 paginiMatrix CPP CombineAbhinav PipalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence Based Practice in Nursing Healthcare A Guide To Best Practice 3rd Edition Ebook PDFDocument62 paginiEvidence Based Practice in Nursing Healthcare A Guide To Best Practice 3rd Edition Ebook PDFwilliam.tavares69198% (50)

- (Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)Document192 pagini(Biophysical Techniques Series) Iain D. Campbell, Raymond A. Dwek-Biological Spectroscopy - Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company (1984)BrunoRamosdeLima100% (1)

- Water Flow Meter TypesDocument2 paginiWater Flow Meter TypesMohamad AsrulÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Wicked Game by Kate BatemanDocument239 paginiA Wicked Game by Kate BatemanNevena Nikolic100% (1)

- Xbox One S Retimer - TI SN65DP159 March 2020 RevisionDocument67 paginiXbox One S Retimer - TI SN65DP159 March 2020 RevisionJun Reymon ReyÎncă nu există evaluări

- D&D 3.5 Edition - Fiendish Codex I - Hordes of The Abyss PDFDocument191 paginiD&D 3.5 Edition - Fiendish Codex I - Hordes of The Abyss PDFIgnacio Peralta93% (15)

- Know Your TcsDocument8 paginiKnow Your TcsRocky SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Document32 pagini3-CHAPTER-1 - Edited v1Michael Jaye RiblezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA 2nd Sem SyllabusDocument6 paginiMBA 2nd Sem SyllabusMohammad Ameen Ul HaqÎncă nu există evaluări

- MGT403 Slide All ChaptersDocument511 paginiMGT403 Slide All Chaptersfarah aqeelÎncă nu există evaluări

- ETSI EG 202 057-4 Speech Processing - Transmission and Quality Aspects (STQ) - Umbrales de CalidaDocument34 paginiETSI EG 202 057-4 Speech Processing - Transmission and Quality Aspects (STQ) - Umbrales de Calidat3rdacÎncă nu există evaluări

- CA Level 2Document50 paginiCA Level 2Cikya ComelÎncă nu există evaluări

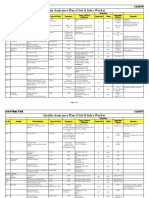

- Quality Assurance Plan - CivilDocument11 paginiQuality Assurance Plan - CivilDeviPrasadNathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Northern Lights - 7 Best Places To See The Aurora Borealis in 2022Document15 paginiNorthern Lights - 7 Best Places To See The Aurora Borealis in 2022labendetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nodal Analysis Collection 2Document21 paginiNodal Analysis Collection 2Manoj ManmathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSS 2 (7th&8th) May2018Document2 paginiDSS 2 (7th&8th) May2018Piara SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- La La Mei Seaside Resto BAR: Final PlateDocument4 paginiLa La Mei Seaside Resto BAR: Final PlateMichael Ken FurioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Signatures: Homework 6Document10 paginiDigital Signatures: Homework 6leishÎncă nu există evaluări

- ICON Finals Casebook 2021-22Document149 paginiICON Finals Casebook 2021-22Ishan ShuklaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Video ObservationDocument8 paginiVideo Observationapi-532202065Încă nu există evaluări

- Invenio Flyer enDocument2 paginiInvenio Flyer enErcx Hijo de AlgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 3 Presenta Tion: Prepared By: Queen Cayell Soyenn Gulo Roilan Jade RosasDocument12 paginiGroup 3 Presenta Tion: Prepared By: Queen Cayell Soyenn Gulo Roilan Jade RosasSeyell DumpÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Grade 4 English HL Test MemoDocument5 pagini2015 Grade 4 English HL Test MemorosinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender and Patriarchy: Crisis, Negotiation and Development of Identity in Mahesh Dattani'S Selected PlaysDocument6 paginiGender and Patriarchy: Crisis, Negotiation and Development of Identity in Mahesh Dattani'S Selected Playsতন্ময়Încă nu există evaluări

- SeaTrust HullScan UserGuide Consolidated Rev01Document203 paginiSeaTrust HullScan UserGuide Consolidated Rev01bong2rmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Photoshoot Plan SheetDocument1 paginăPhotoshoot Plan Sheetapi-265375120Încă nu există evaluări

- Angeles City National Trade SchoolDocument7 paginiAngeles City National Trade Schooljoyceline sarmientoÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Do I Predict Event Timing Saturn Nakshatra PDFDocument5 paginiHow Do I Predict Event Timing Saturn Nakshatra PDFpiyushÎncă nu există evaluări