Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

SALES Case Digests

Încărcat de

IvyGwynn2140 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

518 vizualizări22 paginiSALES Case Digests

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentSALES Case Digests

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

518 vizualizări22 paginiSALES Case Digests

Încărcat de

IvyGwynn214SALES Case Digests

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 22

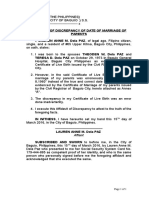

G.R. No.

170405

February 2, 2010

RAYMUNDO S. DE LEON, Petitioner,

vs.

BENITA T. ONG. Respondent.

ISSUE: Whether the parties entered into a contract

of sale or a contract to sell. // Void Sale Or Double

Sale?

On March 10, 1993, petitioner Raymundo S. de

Leon sold three parcels of land with improvements

situated in Antipolo, Rizal to respondent Benita T.

Ong. Respondent was a licensed real estate

broker. As these properties were mortgaged to Real

Savings and Loan Association, Incorporated

(RSLAI), petitioner and respondent executed a

notarized deed of absolute sale with assumption of

mortgage.

***consideration of the sum P1.1 million,

terms: 1. That upon full payment of [respondent] of

the amount of P415,000, [petitioner] shall execute

and sign a deed of assumption of mortgage in favor

of [respondent] without any further cost

whatsoever;

2. That [respondent] shall assume payment of the

outstanding loan of P684,500)with REAL SAVINGS

AND LOAN, Cainta, Rizal ***

Pursuant to this deed, respondent gave petitioner

P415,500 as partial payment. Petitioner, on the

other hand, handed the keys to the properties and

wrote a letter informing RSLAI of the sale and

authorizing it to accept payment from respondent

and release the certificates of title.

Thereafter, respondent made repairs and

improvements on the properties; informed RSLAI of

her agreement with petitioner for her to assume

petitioners outstanding loan. RSLAI required her to

undergo credit investigation.

Subsequently, respondent learned that petitioner

again sold the same properties to one Leona Viloria

after March 10, 1993 and changed the locks,

rendering the keys he gave her useless.

Respondent thus proceeded to RSLAI to inquire

about the credit investigation. However, she was

informed that petitioner had already paid the

amount due and had taken back the certificates of

title. Respondent persistently contacted petitioner

but her efforts proved futile.

Respondent filed a complaint for specific

performance, declaration of nullity of the second

sale and damages in RTC.

RESPONDENT: Since petitioner had previously

sold the properties to her on March 10, 1993, he no

longer had the right to sell the same to Viloria.

Thus, petitioner fraudulently deprived her of the

properties.

PETITIONER: He claimed that since the

transaction was subject to a condition (i.e., that

RSLAI approve the assumption of mortgage), they

only entered into a contract to sell. Inasmuch as

respondent did apply for a loan from RSLAI, the

condition did not arise. Consequently, the sale was

not perfected and he could freely dispose of the

properties.

RTC dismissed case for lack of cause of action.

The perfection of a contract of sale depended on

RSLAIs approval of the assumption of mortgage.

Since RSLAI did not allow respondent to assume

petitioners obligation, the RTC held that the sale

was never perfected.

Respondent appealed to the CA:

The March 10, 2003 contract executed by the

parties did not impose any condition on the sale

and held that the parties entered into a contract of

sale. The CA upheld the sale to respondent and

nullified the sale to Viloria. It likewise ordered

respondent to reimburse petitioner P715,250 (or

the amount he paid to RSLAI). Petitioner, on the

other hand, was ordered to deliver the certificates

of titles to respondent and pay her P50,000 moral

damages and P15,000 exemplary damages.

Petition to SC:

PETITIONER: insists that he entered into a contract

to sell since the validity of the transaction was

subject to a suspensive condition, that is, the

approval by RSLAI of respondents assumption of

mortgage. Because RSLAI did not allow

respondent to assume his (petitioners) obligation,

the condition never materialized. Consequently,

there was no sale.

RESPONDENT: asserts that they entered into a

contract of sale as petitioner already conveyed full

ownership of the subject properties upon the

execution of the deed.

The RTC ruled that it was a contract to sell while

the CA held that it was a contract of sale.

In a contract of sale, the seller conveys ownership

of the property to the buyer upon the perfection of

the contract. Should the buyer default in the

payment of the purchase price, the seller may

either sue for the collection thereof or have the

contract judicially resolved and set aside.

A contract to sell is subject to a positive suspensive

condition. The buyer does not acquire ownership of

the property until he fully pays the purchase price.

The deed executed by the parties (as previously

quoted) stated that petitioner sold the properties to

respondent "in a manner absolute and

irrevocable" for a sum of P1.1 million. With regard

to the manner of payment, it required respondent to

pay P415,500 in cash to petitioner upon the

execution of the deed, with the balance payable

directly to RSLAI (on behalf of petitioner) within a

reasonable time. Nothing in said instrument implied

that petitioner reserved ownership of the properties

until the full payment of the purchase price. On the

contrary, the terms and conditions of the deed only

affected the manner of payment, not the immediate

transfer of ownership (upon the execution of the

notarized contract) from petitioner as seller to

respondent as buyer. Otherwise stated, the said

terms and conditions pertained to the performance

of the contract, not the perfection thereof nor the

transfer of ownership.

In this instance, petitioner executed a notarized

deed of absolute sale in favor of respondent.

Moreover, not only did petitioner turn over the keys

to the properties to respondent, he also authorized

RSLAI to receive payment from respondent and

release his certificates of title to her. The totality of

petitioners acts clearly indicates that he had

unqualifiedly delivered and transferred ownership of

the properties to respondent. Clearly, it was a

contract of sale the parties entered into.

Void Sale Or Double Sale?

This case involves a double sale as the disputed

properties were sold validly on two separate

occasions by the same seller to the two different

buyers in good faith.

*Article 1544 of the Civil Code*

This provision clearly states that the rules on

double or multiple sales apply only to purchasers in

good faith. Needless to say, it disqualifies any

purchaser in bad faith.

Was respondent a purchaser in good faith? Yes.

Respondent purchased the properties, knowing

they were encumbered only by the mortgage to

RSLAI. According to her agreement with petitioner,

respondent had the obligation to assume the

balance of petitioners outstanding obligation to

RSLAI. Consequently, respondent informed RSLAI

of the sale and of her assumption of petitioners

obligation.

However,

because

petitioner

surreptitiously paid his outstanding obligation and

took back her certificates of title, petitioner himself

rendered respondents obligation to assume

petitioners indebtedness to RSLAI impossible to

perform.

Article 1266. The debtor in obligations to do shall

be released when the prestation become legally or

physically impossible without the fault of the obligor.

respondent must pay petitioner P684,500, the

amount stated in the deed. This is because the

provisions, terms and conditions of the contract

constitute the law between the parties. Moreover,

the deed itself provided that the assumption of

mortgage "was without any further cost

whatsoever." Petitioner, on the other hand, must

deliver the certificates of title to respondent. We

likewise affirm the award of damages.

WHEREFORE, the July 22, 2005 decision and

November 11, 2005 resolution of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 59748 are

hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION insofar as

respondent Benita T. Ong is ordered to pay

petitioner

Raymundo

de

Leon P684,500

representing the balance of the purchase price as

provided in their March 10, 1993 agreement.

G.R. No. 165168

July 9, 2010

SPS. NONILON (MANOY) and IRENE

MONTECALVO, Petitioners,

vs.

HEIRS (Substitutes) OF EUGENIA T. PRIMERO,

represented by their Attorney-in-Fact,

ALFREDO T. PRIMERO, JR., Respondents

ISSUE: Whether the said Agreement is a contract

of sale or a contract to sell.

The property involved is a portion of a parcel of

land known as Lot No. 263 located at Sabayle

Street, Iligan City, which has an area of 860 square

meters covered by Original Certificate of Title

(OCT) No. 0-271 registered in the name of Eugenia

Primero (Eugenia), married to Alfredo Primero, Sr.

(Alfredo).

In the early 1980s, Eugenia leased the lot to

petitioner Irene Montecalvo (Irene) for a monthly

rental of P500.00. On January 13, 1985, Eugenia

entered into an un-notarized Agreement with Irene,

where the former offered to sell the property to the

latter for P1,000.00 per square meter. They agreed

that Irene would deposit the amount ofP40,000.00

which shall form part of the down payment

equivalent to 50% of the purchase price. They also

stipulated that during the term of negotiation of 30

to 45 days from receipt of said deposit, Irene would

pay the balance ofP410,000.00 on the down

payment. In case Irene defaulted in the payment of

the down payment, the deposit would be returned

within 10 days from the lapse of said negotiation

period and the Agreement deemed terminated.

However, if the negotiations pushed through, the

balance of the full value of P860,000.00 or the net

amount ofP410,000.00 would be paid in 10 equal

monthly installments from receipt of the down

payment, with interest at the prevailing rate.

Irene failed to pay the full down payment within the

stipulated

30-45-day

negotiation

period.

Nonetheless, she continued to stay on the disputed

property, and still made several payments with an

aggregate amount ofP293,000.00. On the other

hand, Eugenia did not return the P40,000.00

deposit to Irene, and refused to accept further

payments only in 1992.

Thereafter, Irene caused a survey of Lot No. 263

and the segregation of a portion equivalent to 293

square meters in her favor. However, Eugenia

opposed her claim and asked her to vacate the

property. Then on May 13, 1996, Eugenia and the

heirs of her deceased husband Alfredo filed a

complaint for unlawful detainer against Irene and

her husband, herein petitioner Nonilon Montecalvo

(Nonilon) before the Municipal Trial Court (MTC) of

Iligan City. During the preliminary conference, the

parties stipulated that the issue to be resolved was

whether their Agreement had been rescinded and

novated. Hence, the MTC dismissed the case for

lack of jurisdiction since the issue is not susceptible

of pecuniary estimation. The MTC's Decision

dismissing the ejectment case became final as

Eugenia and her children did not appeal therefrom.

On June 18, 1996, Irene and Nonilon retaliated by

instituting Civil Case No. II-3588 with the RTC of

Lanao del Norte for specific performance, to

compel Eugenia to convey the 293-square meter

portion of Lot No. 263.

RTC:

IRENE: testified that after their Agreement for the

purpose of negotiating the sale of Lot No. 263 failed

to materialize, she and Eugenia entered into an oral

contract of sale and agreed that the amount

of P40,000.00 she earlier paid shall be considered

as down payment. Irene claimed that she made

several payments amounting to P293,000.00 which

prompted Eugenia's daughters Corazon Calacat

(Corazon) and Sylvia Primero (Sylvia) to ask Engr.

Antonio Ravacio (Engr. Ravacio) to conduct a

segregation survey on the subject property.

Thereafter, Irene requested Eugenia to execute the

deed of sale, but the latter refused to do so

because her son, Atty. Alfredo Primero, Jr. (Atty.

Primero)- who became the representative because

Eugenia died, would not agree.

RESPONDENTS: At the time of the signing of the

Agreement on January 13, 1985, Eugenia's

husband, Alfredo, was already dead. Eugenia

merely managed or administered the subject

property and had no authority to dispose of the

same since it was a conjugal property. In addition,

respondents

asserted

that

the

deposit

of P40,000.00 was retained as rental for the subject

property.

RTC dismissed complaint and counterclaim;

ordered petitioners to pay respondents rentals due.

Petitioners appealed to the CA: affirmed RTC

decision; motion denied for lack of merit.

SC:

The Agreement dated January 13, 1985 is a

contract to sell. Hence, with petitioners' noncompliance with its terms and conditions, the

obligation of the respondents to deliver and execute

the corresponding deed of sale never arose.

In the Agreement, Eugenia, as owner, did not

convey her title to the disputed property to Irene

since the Agreement was made for the purpose of

negotiating the sale of the 860-square meter

property.

On this basis, we are more inclined to characterize

the agreement as a contract to sell rather than a

contract of sale. Although not by itself controlling,

the absence of a provision in the Agreement

transferring title from the owner to the buyer is

taken as a strong indication that the Agreement is a

contract to sell.

In a contract to sell, the prospective seller explicitly

reserves the transfer of title to the prospective

buyer, meaning, the prospective seller does not as

yet agree or consent to transfer ownership of the

property subject of the contract to sell until the

happening of an event, which for present purposes

we shall take as the full payment of the purchase

price. A contract to sell is commonly entered into in

order to protect the seller against a buyer who

intends to buy the property in installment by

withholding ownership over the property until the

buyer effects full payment therefor.

In this case, the Agreement expressly provided that

it was "entered into for the purpose of negotiating

the sale of the above referred property between the

same parties herein x x x." The term of the

negotiation shall be for a period of 30-45 days from

receipt of the P40,000.00 deposit and the buyer

has to pay the balance of the 50% down payment

amounting to P410,000.00 within the said period of

negotiation. Thereafter, an Agreement to Sell shall

be executed by the parties and the remainder of the

purchase price amounting to another P410,000.00

shall be paid in 10 equal monthly installments from

receipt of the down payment. The assumption of

both parties that the purpose of the Agreement was

for negotiating the sale of Lot No. 263, in its

entirety, for a definite price, with a specific period

for payment of a specified down payment, and the

execution of a subsequent contract for the sale of

the same on installment payments leads to no other

conclusion than that the predecessor-in-interest of

the herein respondents and the herein petitioner

Irene entered into a contract to sell.

It is a fundamental principle that for a contract of

sale to be valid, the following elements must be

present: (a) consent or meeting of the minds; (b)

determinate subject matter; and (3) price certain in

money or its equivalent. Until the contract of sale is

perfected, it cannot, as an independent source of

obligation, serve as a binding juridical relation

between the parties.

Section 1 of Rule 133 of the Rules of Court

provides that in civil cases, the party having the

burden of proof must establish his case by a

preponderance of evidence. However, the evidence

presented by the petitioners, as considered above,

fails to convince this Court that Eugenia gave her

consent to the purported oral deed of sale for the

293-square meter portion of her property. We are

hence in agreement with the finding of the CA that

there was no contract of sale between the parties.

As a consequence, petitioners cannot rightfully

compel the successors-in-interest of Eugenia to

execute a deed of absolute sale in their favor.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The

November 28, 2003 Decision of the Court of

Appeals affirming the October 22, 2001 Decision of

the Regional Trial Court of Lanao del Norte, Branch

2, is hereby AFFIRMED.

G.R. No. 169900

March 18, 2010

MARIO SIOCHI, Petitioner,

vs.

ALFREDO GOZON, WINIFRED GOZON, GIL

TABIJE, INTER-DIMENSIONAL REALTY, INC.,

and ELVIRA GOZON, Respondents.

G.R. No. 169977

INTER-DIMENSIONAL REALTY, INC., Petitioner,

vs.

MARIO SIOCHI, ELVIRA GOZON, ALFREDO

GOZON, and WINIFRED GOZON, Respondents.

ISSUE: Whether or not the Agreement to Buy and

Sell is valid without the consent of the other

spouse.

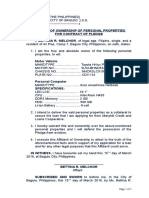

This case involves a 30,000 sq.m. parcel of land

(property) covered by TCT No. 5357 situated in

Malabon, Metro Manila and is registered in the

name of "Alfredo Gozon (Alfredo), married to Elvira

Gozon (Elvira)."

On 23 December 1991, Elvira filed with the Cavite

RTC a petition for legal separation against her

husband Alfredo. On 2 January 1992, Elvira filed a

notice of lis pendens, which was then annotated on

TCT No. 5357.

On 31 August 1993, while the legal separation case

was still pending, Alfredo and Mario Siochi (Mario)

entered into an Agreement to Buy and

Sell (Agreement) involving the property for the price

of P18 million. Among the stipulations in the

Agreement were that Alfredo would: (1) secure an

Affidavit from Elvira that the property is Alfredos

exclusive property and to annotate the Agreement

at the back of TCT No. 5357; (2) secure the

approval of the Cavite RTC to exclude the property

from the legal separation case; and (3) secure the

removal of the notice of lis pendens pertaining to

the said case and annotated on TCT No. 5357.

However, despite repeated demands from Mario,

Alfredo failed to comply with these stipulations.

After paying the P5 million earnest money as partial

payment of the purchase price, Mario took

possession of the property in September 1993. On

6 September 1993, the Agreement was annotated

on TCT No. 5357.

On 29 June 1994, the Cavite RTC rendered a

judgment decreeing the legal separation.

Accordingly, petitioner Elvira Robles Gozon is

entitled to live separately from respondent Alfredo

Gozon without dissolution of their marriage bond.

The conjugal partnership of gains of the spouses is

hereby declared DISSOLVED and LIQUIDATED.

Being the offending spouse, respondent is deprived

of his share in the net profits and the same is

awarded to their child Winifred R. Gozon whose

custody is awarded to petitioner. The Cavite RTC

held that it is deemed conjugal property.

On 22 August 1994, Alfredo executed a Deed of

Donation over the property in favor of their

daughter, Winifred Gozon (Winifred). The Register

of Deeds of Malabon, Gil Tabije, cancelled TCT No.

5357 and issued TCT No. M-10508 in the name of

Winifred, without annotating the Agreement and the

notice of lis pendens on TCT No. M-10508.

On 26 October 1994, Alfredo, by virtue of a Special

Power of Attorney executed in his favor by Winifred,

sold the property to Inter-Dimensional Realty, Inc.

(IDRI) for P18 million. IDRI paid Alfredo P18 million,

representing

full

payment

for

the

property. Subsequently, the Register of Deeds of

Malabon cancelled TCT No. M-10508 and issued

TCT No. M-10976 to IDRI.

Mario then filed with the Malabon RTC a complaint

for Specific Performance and Damages, Annulment

of Donation and Sale, with Preliminary Mandatory

and Prohibitory Injunction and/or Temporary

Restraining Order.

On 3 April 2001, the Malabon RTC rendered a

decision: The Register of Deeds of Malabon, Metro

Manila is hereby ordered to cancel Certificate of

Title Nos. 10508 "in the name of Winifred Gozon"

and M-10976 "in the name of Inter-Dimensional

Realty, Inc.," and to restore Transfer Certificate of

Title No. 5357 "in the name of Alfredo Gozon,

married to Elvira Robles" with the Agreement to

Buy and Sell dated 31 August 1993 fully annotated

therein.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed the

Malabon RTCs decision with modification. The sale

of the subject land by defendant Alfredo Gozon to

plaintiff-appellant Siochi is declared null and void.

of the consent of one of the spouse renders the

entire sale void, including the portion of the

conjugal property pertaining to the spouse who

contracted the sale. Even if the other spouse

actively participated in negotiating for the sale of

the property, that other spouses written consent to

the sale is still required by law for its validity. The

Agreement entered into by Alfredo and Mario was

without the written consent of Elvira. Thus, the

Agreement is entirely void. As regards Marios

contention that the Agreement is a continuing offer

which may be perfected by Elviras acceptance

before the offer is withdrawn, the fact that the

property was subsequently donated by Alfredo to

Winifred and then sold to IDRI clearly indicates that

the offer was already withdrawn.

Mario and IDRI appealed the decision:

MARIO: alleges that the Agreement should be

treated as a continuing offer which may be

perfected by the acceptance of the other spouse

before the offer is withdrawn. Since Elviras conduct

signified her acquiescence to the sale, Mario prays

for the Court to direct Alfredo and Elvira to execute

a Deed of Absolute Sale over the property upon his

payment of P9 million to Elvira.

IDRI: Mario alleges that the Agreement should be

treated as a continuing offer which may be

perfected by the acceptance of the other spouse

before the offer is withdrawn. Since Elviras conduct

signified her acquiescence to the sale, Mario prays

for the Court to direct Alfredo and Elvira to execute

a Deed of Absolute Sale over the property upon his

payment of P9 million to Elvira.

This case involves the conjugal property of Alfredo

and Elvira. Since the disposition of the property

occurred after the effectivity of the Family Code, the

applicable law is the Family Code. Article 124.

In this case, Alfredo was the sole administrator of

the property because Elvira, with whom Alfredo was

separated in fact, was unable to participate in the

administration of the conjugal property. However,

as sole administrator of the property, Alfredo still

cannot sell the property without the written consent

of Elvira or the authority of the court. Without such

consent or authority, the sale is void. The absence

With regard to IDRI, we agree with the Court of

Appeals in holding that IDRI is not a buyer in good

faith. As found by the RTC Malabon and the Court

of Appeals, IDRI had actual knowledge of facts and

circumstances which should impel a reasonably

cautious person to make further inquiries about the

vendors title to the property. The representative of

IDRI testified that he knew about the existence of

the notice of lis pendens on TCT No. 5357 and the

legal separation case filed before the Cavite RTC.

Thus, IDRI could not feign ignorance of the Cavite

RTC decision declaring the property as conjugal.

Under Section 77 of Presidential Decree No.

1529,19 the notice of lis pendens may be cancelled

(a) upon order of the court, or (b) by the Register of

Deeds upon verified petition of the party who

caused the registration of the lis pendens. In this

case, the lis pendens was cancelled by the

Register of Deeds upon the request of Alfredo.

WHEREFORE,

we DENY the

petitions.

We AFFIRM the 7 July 2005 Decision of the Court

of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 74447 with the

following MODIFICATIONS:

(1) We DELETE the portions regarding the

forfeiture of Alfredo Gozons one-half

undivided share in favor of Winifred Gozon

and the grant of option to Winifred Gozon

whether or not to dispose of her undivided

share in the property; and

(2) We ORDER Alfredo Gozon and Winifred

Gozon to pay Inter-Dimensional Realty, Inc.

jointly and severally the Eighteen Million

Pesos (P18,000,000) which was the amount

paid by Inter-Dimensional Realty, Inc. for

the property, with legal interest computed

from the finality of this Decision.

On October 1, 1994, petitioner Hyatt Elevators and

Escalators Corporation entered into an "Agreement

to Service Elevators" (Service Agreement) with

respondent Cathedral Heights Building Complex

Association, Inc., where petitioner was contracted

to maintain four passenger elevators installed in

respondent's

building.

Under

the

Service

Agreement, the duties and obligations of petitioner

included monthly inspection, adjustment and

lubrication of machinery, motors, control parts and

accessory equipments, including switches and

electrical wirings. Section D (2) of the Service

Agreement provides that respondent shall pay for

the additional charges incurred in connection with

the repair and supply of parts.

Petitioner claims that during the period of April 1997

to July 1998 it had incurred expenses amounting to

Php 1,161,933.47 in the maintenance and repair of

the four elevators as itemized in a statement of

account. Petitioner demanded from respondent the

payment of the aforesaid amount allegedly through

a series of demand letters, the last one sent on July

18, 2000. Respondent, however, refused to pay the

amount.

Petitioner filed with the Regional Trial Court (RTC),

Branch 100, Quezon City, a Complaint for sum of

money against respondent.

On March 5, 2003, the RTC rendered Judgment in

favor of the plaintiffs. The RTC held that based on

the sales invoices presented by petitioner, a

contract of sale of goods was entered into between

the parties. Since petitioner was able to fulfill its

obligation, the RTC ruled that it was incumbent on

respondent to pay for the services rendered.

G.R. No. 173881

December 1, 2010

HYATT ELEVATORS and ESCALATORS

CORPORATION, Petitioner,

vs.

CATHEDRAL HEIGHTS BUILDING COMPLEX

ASSOCIATION, INC., Respondent.

ISSUE: Whether there exists a perfected contract

of sale.

RTC

denied

Reconsideration.

respondents

Motion

for

CA rendered a Decision finding merit in

respondent's appeal. The CA ruled that respondent

did not give its consent to the purchase of the spare

parts allegedly installed in the defective elevators.

Aside from the absence of consent, the CA also

held that there was no perfected contract of sale

because there was no meeting of minds upon the

price. On this note, the CA ruled that the Service

Agreement did not give petitioner the unbridled

license to purchase and install any spare parts and

demand, after the lapse of a considerable length of

time, payment of these prices from respondent

according to its own dictated price.

RTC

denied

petitioners

Reconsideration., went to SC:

Motion

for

RESPONDENT: contends that petitioner had failed

to follow the SOP since no purchase orders from

respondent's Finance Manager, or Board of

Directors relating to the supposed parts used were

secured prior to the repairs. Consequently, since

the repairs were not authorized, respondent claims

that it has no way of verifying whether the parts

were actually delivered and installed as alleged by

petitioner.

A perusal of petitioner's petition and evidence in the

RTC shows that the main thrust of its case is

premised on the following claims: first, that the

nature and operations of a hospital necessarily

dictate that the elevators are in good running

condition at all times; and, second, that there was a

verbal agreement between petitioner's service

manager and respondent's building engineer that

the elevators should be running in good condition at

all times and breakdowns should only last one day.

This Court finds that the testimony of Sua alone is

insufficient to prove the existence of the verbal

agreement, especially in view of the fact that

respondent insists that the SOP should have been

followed. It is an age-old rule in civil cases that one

who alleges a fact has the burden of proving it and

a mere allegation is not evidence.

Based on the evidence presented in the RTC, it is

clear to this Court that petitioner had failed to

secure the necessary purchase orders from

respondent's Board of Directors, or Finance

Manager, to signify their assent to the price of the

parts to be used in the repair of the elevators.

The fixing of the price can never be left to the

decision of one of the contracting parties. But a

price fixed by one of the contracting parties, if

accepted by the other, gives rise to a perfected

sale

There would have been a perfected contract of sale

had respondent accepted the price dictated by

petitioner even if such assent was given after the

services were rendered. There is, however, no

proof of such acceptance on the part of respondent.

This Court shares the observation of the CA that

the signatures of receipt by the information clerk or

the guard on duty on the sales invoices and

delivery receipts merely pertain to the physical

receipt of the papers. It does not indicate that the

parts stated were actually delivered and installed.

Moreover, because petitioner failed to prove the

existence of the verbal agreement which allegedly

authorized the aforementioned individuals to sign in

respondents behalf, such signatures cannot be

tantamount to an approval or acceptance by

respondent of the parts allegedly used and the

price quoted by petitioner.

Withal, this Court rules that petitioner's claim must

fail for the following reasons: first, petitioner failed

to prove the existence of the verbal agreement that

would authorize non-observance of the SOP;

second, petitioner failed to prove that such

procedure was the practice since 1994; and, third,

there was no perfected contract of sale between

the parties as there was no meeting of minds upon

the price.

WHERFORE, premises considered, the petition

is DENIED. The April 20, 2006 Decision and July

31, 2006 Resolution of the Court of Appeals, in CAG.R. CV No. 80427, are AFFIRMED.

G.R. No. 161524

January 27, 2006

LAURA M. MARNELEGO, Petitioner,

vs.

BANCO FILIPINO SAVINGS AND MORTGAGE

BANK, Respondent

ISSUE: Whether there is a perfected contract of

sale between petitioner and respondent Banco

Filipino concerning the property in question.

In September 1980, Spouses Patrick and Beatrize

Price and petitioner Laura Marnelego executed a

Deed of Conditional Sale over a parcel of land

located at Houston Street, BF Homes, Paraaque,

Metro Manila and its improvements. The contract

showed that the property was mortgaged to

respondent Banco Filipino Savings and Mortgage

Bank (Banco Filipino) and BF Homes, and that

Spouses Price agreed to pay the amortizations for

the first six months beginning August 1980 to

January 1981 while petitioner would assume the

succeeding amortizations.

It appears, however, that when the parties faltered

on the amortizations, respondent bank foreclosed

the mortgage and acquired the property at public

auction. It later consolidated the title to the property

in its name after petitioner failed to redeem it. The

Regional Trial Court of Makati issued a writ of

possession in February 1984.

There were letters sent between the parties.

On November 22, 1995, after the bank resumed its

operations, it sent a letter to petitioner demanding

that they vacate the premises within five days from

receipt thereof.

Petitioner filed a complaint with the Regional Trial

Court of Paraaque for specific performance.

Invoking the letter dated September 20, 1984 of Mr.

Ricardo J. Gabriel, Assistant Manager, Real Estate

Department and Secretary of the Committee on

Disposal of Bank Properties, petitioner claimed that

the bank has approved her proposal for the

acquisition of the property. Petitioner prayed that

the court order the bank to execute the necessary

Deed of Sale of the property in question.

The trial court ruled in favor of petitioner. It held that

there was a perfected contract of sale between

petitioner and respondent; that the parties have

agreed on the purchase price of P362,000.00; and

that the terms set in the banks letter of September

20, 1984 are merely conditions in the performance

of the obligation and not a condition for the birth of

the contract.

The Court of Appeals reversed the decision of the

trial court. It found that there was no perfected

contract of sale between petitioner and respondent

bank. There was merely a series of offers and

counter-offers between the parties but they never

reached an agreement as to the purchase price.

petitioner that the bank has approved her request

to repurchase the property in the amount

ofP362,000.00 but subject to the following terms

and conditions: (1) cash payment of P310,000.00

upon approval of the request/proposal, and (2)

balance of P52,000.00 to be paid within one (1)

year at the rate of 35% interest per

annum. Petitioner, in her letter to the bank dated

October 9, 1984, made a counter-offer to pay a

down payment of P100,000.00 and to pay the

balance in 5 equal installments to be paid in 5

years with interest. Before the bank could act on

petitioners proposal, the Central Bank of the

Philippines ordered the closure of Banco Filipino

and placed it under liquidation. Thus on December

5, 1985, petitioner wrote to Mr. Alberto V. Reyes,

Deputy Liquidator of Banco Filipino, proposing to

purchase the property under the following terms

and conditions:

1. Purchase price to be determined by the

Liquidator

2. Purchase price to be payable as follows:

2.A. P120,000.00 to be deposited immediately

and to be lodged as A/P for the undersigned

Petition to SC: Petitioner argues:

1. The Court of Appeals gravely erred in finding

that there was no perfected contract between the

parties.

2. The Court of Appeals gravely erred in not

finding that the modified terms of payment

offered by petitioner was [sic] merely a condition

on the performance of an obligation, not a

condition imposed on the perfection of the

contract.

It has been ruled that a definite agreement on the

manner of payment of the purchase price is an

essential element in the formation of a binding and

enforceable contract of sale. The exchange of

letters between petitioner and respondent shows

that petitioner first offered to buy the property

for P310,000.00, considering the numerous repairs

that had to be done in the house. Respondent, in its

letter dated September 20, 1984, informed

2.B. Balance to be paid once the restraining

order/preliminary injunction is lifted by the officers

of Banco Filipino

On April 3, 1986, the Deputy Liquidator replied that

they can only consider the sale of the property after

the lifting of the Temporary Restraining Order

issued by the Supreme Court and said sale shall be

subject to the Central Bank rules and regulations.

Clearly, there was no agreement yet between the

parties as regards the purchase price and the

manner and schedule of its payment. Neither of

them had expressed acceptance of the other

partys offer and counter-offer.

Notable is petitioners letter to the banks Deputy

Liquidator, Mr. Alberto V. Reyes, which reveals that

she herself believed that no agreement has yet

been reached by the parties as regards the

purchase

price

after

the

exchange

of

communication between her and the bank. In said

letter, she made a totally new proposal for

consideration of the banks Liquidator that the

purchase price shall be determined by the

Liquidator; that she would deposit the amount

of P120,000.00 to be lodged in her accounts

payable; and that she would pay the balance after

the lifting of the temporary restraining order issued

by the Court on the banks transactions.

We find, therefore, that the Court of Appeals did not

err in reversing the decision of the trial court. As the

parties have not agreed on the purchase price for

the property, petitioners action for specific

performance against the bank must fail.

IN VIEW WHEREOF, the petition is DENIED.

G.R. No. 159373

November 16, 2006

JOSE R. MORENO, JR., Petitioner,

vs.

Private Management Office (formerly, ASSET

PRIVATIZATION TRUST), Respondent.

ISSUE: Whether or not there was a perfected

contract of sale over the subject floors at the price

ofP21,000,000.00.

The subject-matter of this complaint is the J.

Moreno Building (formerly known as the North

Davao Mining Building) or more specifically, the

2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th floors of the building.

Plaintiff is the owner of the Ground Floor, the 7th

Floor and the Penthouse of the J. Moreno Building

and the lot on which it stands.

Defendant is the owner of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and

6th floors of the building, the subject-matter of this

suit.

On February 13, 1993, the defendant called for a

conference for the purpose of discussing plaintiffs

right of first refusal over the floors of the building

owned by defendant. At said meeting, defendant

informed plaintiff that the proposed purchase price

for said floors was P21,000,000.00;

On February 22, 1993, defendant, in a letter signed

by its Trustee, Juan W. Moran, informed plaintiff

thru Atty. Jose Feria, Jr., that the Board of Trustees

(BOT) of APT "is in agreement that Mr. Jose

Moreno, Jr. has the right of first refusal" and

requested plaintiff to deposit 10% of the "suggested

indicative price" ofP21.0 million on or before

February 26, 1993 ;

Plaintiff paid the P2.1 million on February 26, 1993.

Then on March 12, 1993, defendant wrote plaintiff

that its Legal Department has questioned the basis

for the computation of the indicative price for the

said floors.

On April 2, 1993, defendant wrote plaintiff that the

APT BOT has "tentatively agreed on a settlement

price of P42,274,702.17" for the said floors;

On August 10, 1994, the trial court ruled in favor of

petitioner Moreno, viz.:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in

favor of plaintiff and against defendant, ordering

defendant to sell the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th

floors of the J. Moreno Building to plaintiff at the

price

of

TWENTY[-]ONE

MILLION

(P21,000,000.00) PESOS; and ordering defendant

to endorse the transaction to the Committee on

Privatization, without costs.

Respondent filed a Motion for Reconsideration. On

November 16, 1994, the trial court denied the

motion for lack of merit.

Respondent appealed with the Court of Appeals.

(dismissed: no perfected contract of sale) Motion

for Reconsideration was denied. Respondent then

filed a Petition for Review on Certiorari.

Contract formation undergoes three distinct stages

preparation or negotiation, perfection or birth, and

consummation. This situation does not obtain in

the case at bar.

The letter of February 22, 1993 and the

surrounding circumstances clearly show that the

parties are not past the stage of negotiation, hence

there could not have been a perfected contract of

sale.

The letter is clear evidence that respondent did not

intend to sell the subject floors at the price certain

ofP21,000,000.00,

The letter clearly states that P21,000,000.00 is

merely a "suggested indicative price" of the subject

floors as it was yet to be approved by the Board of

Trustees. Before the Board could confirm the

suggested indicative price, the Committee on

Privatization must first approve the terms of the

sale or disposition.

Petitioner further argues that the "suggested

indicative price" of P21,000,000.00 is not a

proposed price, but the selling price indicative of

the value at which respondent was willing to

sell. Petitioner posits that under Section 14, Rule

130 of the Revised Rules of Court, the term should

be taken in its ordinary and usual acceptation and

should be taken to mean as a price which is

"indicated" or "specified" which, if accepted, gives

rise to a meeting of minds. We do not agree.

It appears in the case at bar that petitioners

construction of the letter of February 22, 1993

that his assent to the "suggested indicative price"

of P21,000,000.00 converted it as the price certain,

thus giving rise to a perfected contract of sale is

petitioners own subjective understanding. As such,

it is not shared by respondent. Under American

jurisprudence, mutual assent is judged by

an objective standard, looking to the express

words the parties used in the contract. Under the

objective theory of contract, understandings and

beliefs are effective only if shared. Based on the

objective manifestations of the parties in the case

at bar, there was no meeting of the minds. That the

letter constituted a definite, complete and certain

offer is the subjective belief of petitioner alone. The

letter in question is a mere evidence of a

memorialization of inconclusive negotiations, or a

mere agreement to agree, in which material term is

left for future negotiations. It is a mere evidence of

the parties preliminary transactions which did not

crystallize into a perfected contract. Preliminary

negotiations or an agreement still involving future

negotiations is not the functional equivalent of a

valid, subsisting agreement. For a valid contract to

have been created, the parties must have

progressed beyond this stage of imperfect

negotiation. But as the records would show, the

parties are yet undergoing the preliminary steps

towards the formation of a valid contract. Having

thus established that there is no perfected contract

of sale in the case at bar, the issue on estoppel is

now moot and academic.

Decision affirmed.

G. R. No. 158149 February 9, 2006

BOSTON BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES, (formerly

BANK OF COMMERCE), Petitioner,

vs.

PERLA P. MANALO and CARLOS MANALO, JR.,

Respondents.

ISSUE: whether petitioner or its predecessors-in-interest,

the XEI or the OBM, as seller, and the respondents, as

buyers, forged a perfect contract to sell over the

property.

1. Xavierville Estate, Inc. (XEI) sold to The Overseas

Bank of Manila (OBM)some residential lots in

Xavierville

subdivision.

Nevertheless,

XEI

continuedselling the residential lots in the subdivision as

agent of OBM.

2. Carlos Manalo, Jr. proposed to XEI, through its

President Emerito Ramos(Ramos), that he will purchase

two lots in the Xavierville subdivision andoffered as part

of the downpayment the P34,887.66 Ramos owed him.

XEI,through Ramos, agreed.

3. In a letter dated August 22, 1972 to Perla Manalo

(Carlos wife), Ramosconfirmed the reservation of the

lots. In the letter he also pegged the price of the lots at

P348,060 with a 20% down payment of the purchase

priceamounting to P69,612.00 (less the P34,887.66

owing from Ramos), payableas soon as XEI resumes its

selling operations; the corresponding Contract of

Conditional Sale would then be signed on or before the

same date. PerlaManalo conformed to the letter

agreement.

4. Thereafter, the spouses constructed a house on the

property. The spouses were notified of XEIs resumption

of selling operations. However,they did not pay the

balance of the downpayment because XEI failed

toprepare a contract of conditional sale and transmit the

same to them. XEIalso billed them for unpaid interests

which they also refused to pay. XEIturned over its

selling operations to OBM.

5. Subsequently, Commercial Bank of Manila (CBM)

acquired the XaviervilleEstate from OBM. CBM

requested Perla Manalo to stop any on-goingconstruction

on the property since it (CBM) was the owner of the lot

and shehad no permission for such construction. Perla

informed them that her husband had a contract with

OBM, through XEI, to purchase the property.She

promised to send CBM the documents. However, she

failed to do so.Thus, CBM filed a complaint for

unlawful detainer against the spouses. Butlater on, CBM

moved to withdraw its complaint because of the issues

raised.In the meantime, CBM was renamed the Boston

Bank of the Philippines.

6. Then, the spouses filed a complaint for specific

performance and damagesagainst the bank before the

RTC. The spouses alleged that they had alwaysbeen

ready and willing to pay the installments on the lots sold

to them but nocontract was forthcoming. The spouses

further alleged that upon their partialpayment of the

downpayment, they were entitled to the execution

anddelivery of a Deed of Absolute Sale covering the

subject lots. During the trial,the spouses adduced in

evidence the separate Contracts of Conditional

Saleexecuted between XEI and 3 other buyers to prove

that XEI continued sellingresidential lots in the

subdivision as agent of OBM after the latter hadacquired

the said lots.

RTC : The trial court ordered the petitioner (Boston

Bank) to execute a Deed of Absolute Sale in favor of the

spouses upon the payment of the spouses of the balance

of the purchase price. It ruled that under the August 22,

1972letter agreement of XEI and the spouses, the parties

had a "completecontract to sell" over the lots, and that

they had already partiallyconsummated the same.

CA: The Court of Appeals sustained the ruling of the

RTC, but declared that thebalance of the purchase price

of the property was payable in fixed amountson a

monthly basis for 120 months, based on the deeds of

conditional saleexecuted by XEI in favor of other lot

buyers.Boston Bank filed a Motion for the

Reconsideration of the decision allegingthat there was

no perfected contract to sell the two lots, as there was

noagreement between XEI and the respondents on the

manner of payment aswell as the other terms and

conditions of the sale. Boston Bank also assertsthat there

is no factual basis for the CA ruling that the terms and

conditionsrelating to the payment of the balance of the

purchase price of the property(as agreed upon by XEI

and other lot buyers in the same subdivision) werealso

applicable to the contract entered into between the

petitioner and therespondents. CA denied the MR.

Based on these two letters, the determination of the

terms of payment of the P278,448.00 had yet to be

agreed upon on or before December 31, 1972, or even

afterwards, when the parties sign the corresponding

contract of conditional sale.

Boston Bank, now petitioner, filed the instant petition for

review on certiorari assailing the CA rulings.

Jurisprudence is that if a material element of a

contemplated contract is left for future negotiations, the

same is too indefinite to be enforceable. And when an

essential element of a contract is reserved for future

agreement of the parties, no legal obligation arises until

such future agreement is concluded

SC:Petitioner posits that, even on the assumption that

there was a perfected contract to sell between the parties,

nevertheless, it cannot be compelled to convey the

property to the respondents because the latter failed to

pay the balance of the downpayment of the property, as

well as the balance of 80% of the purchase price, thus

resulting in the extinction of its obligation to convey title

to the lots to the Respondents.

Respondents further posit that the terms and conditions

to be incorporated in the "corresponding contract of

conditional sale" to be executed by the parties would be

the same as those contained in the contracts of

conditional sale executed by lot buyers in the

subdivision. After all, they maintain, the contents of the

corresponding contract of conditional sale referred to in

the August 22, 1972 letter agreement envisaged those

contained in the contracts of conditional sale that XEI

and other lot buyers executed.

A definite agreement as to the price is an essential

element of a binding agreement to sell personal or real

property because it seriously affects the rights and

obligations of the parties. Price is an essential element in

the formation of a binding and enforceable contract of

sale. The fixing of the price can never be left to the

decision of one of the contracting parties. But a price

fixed by one of the contracting parties, if accepted by the

other, gives rise to a perfected sale.

In a contract to sell property by installments, it is not

enough that the parties agree on the price as well as the

amount of downpayment. The parties must, likewise,

agree on the manner of payment of the balance of the

purchase price and on the other terms and conditions

relative to the sale. Even if the buyer makes a

downpayment or portion thereof, such payment cannot

be considered as sufficient proof of the perfection of any

purchase and sale between the parties.

It bears stressing that the respondents failed and refused

to pay the balance of the downpayment and of the

purchase price of the property amounting to P278,448.00

despite notice to them of the resumption by XEI of its

selling operations. The respondents enjoyed possession

of the property without paying a centavo. On the other

hand, XEI and OBM failed and refused to transmit a

contract of conditional sale to the Respondents. The

respondents could have at least consigned the balance of

the downpayment after notice of the resumption of the

selling operations of XEI and filed an action to compel

XEI or OBM to transmit to them the said contract;

however, they failed to do so.

As a consequence, respondents and XEI (or OBM for

that matter) failed to forge a perfected contract to sell the

two lots; hence, respondents have no cause of action for

specific performance against petitioner. Republic Act

No. 6552 "Realty Installment Buyer Act." applies only to

a perfected contract to sell and not to a contract with no

binding and enforceable effect.

The petition is granted. The decision of CA is reversed

and set aside.

he will stop paying rentals for the said unit after

September 30

c.

In case Platinum Plans has an outstanding loan of

less than P2 million with the bank as of December 1993,

Cucueco shall assume the same and pay the difference

from the remaining P2 million

Cucueco likewise claimed that Platinum Plans accepted

his offerby encashing the checks he issued. However,

he was surprised to learn that Platinum Plans had

changed the due date of the installment payment to

September 30, 1993.

Respondent argued that there was a perfected sale

between him and Platinum plans and as such, he may

validly demand from the petitioner to execute the

necessary deed of sale transferring ownership and title

over the property in his favor

Platinum Plans denied Cucuecos allegations and

asserted that Cucuecos initial down payment was

forfeited based on the following terms and conditions:

a.

The terms of payment only includes two

installments (August 1993 and September 1993)

PLATINUM PLANS PHILS INC V. CUCUECO 488

SCRA 156 (2006)

b.

In case of non-compliance on the part of the

vendee, all installments made shall be forfeited in favor

of the vendor Platinum Plans

ISSUE: ISSUE: whether or not the contract is a

perfected contract of sale

c.

Ownership over the property shall not pass until

payment of the full purchase price

FACTS: Respondent Cucueco filed a case for specific

performance with damages against petitioner Platinum

Plans pursuant to an alleged contract of sale executed by

them for the purchase of a condominium unit.

Petitioners anchor their argument on the claim that there

was no meeting of the minds between the two parties, as

evidenced by their letter of non-acceptance.

According to the respondent: sometime in July 1993, he

offered to buy from petitioner Platinum Plans Phils a

condominium unit he was leasing from the latter for P 4

million payable in 2 installments of P2 million with the

following terms and conditions:

The trial court ruled in favor of Platinum, citing that

since the element of consent was absent there was no

perfected contract. The trial court ordered Platinum

Plans to return the P2 million they had received from

Cucueco, and for Cucueco to pay Platinum Plans rentals

in arrears for the use of the unit.

a.

Cucueco will issue a check for P100,00 as earnest

money

b.

He will issue a post-dated check for P1.9 million to

be encashed on September 30, 1993 on the condition that

Upon appeal, CA held that there was a perfected

contract despite the fact that both parties never agreed on

the date of payment of the remaining balance. CA

ordered Cucueco to pay the remaining balance of the

purchase price and for Platinum Plans, to execute a deed

of sale over the property

HELD: it is a contract to sell.

In a contract of sale, the vendor cannot recover

ownership of the thing sold until and unless the contract

itself is resolved and set aside. Art 1592 provides:

In the sale of immovable property, even though it may

have been stipulated that upon failure to pay the price at

the time agreed upon, the rescission of the contract shall

of right take place, the vendee may pay, even after the

expiration of the period, as long as no demand for

rescission of the contract has been upon him either

judicially or by a notarial act. After the demand, the

court may not grant him a new term.

Based on the above provision, a party who fails to

invoke judicially or by notarial act would be prevented

from blocking the consummation of the same in light of

the precept that mere failure to fulfill the contract does

not by itself have the effect of rescission.

On the other hand, a contract to sell is bilateral contract

whereby the prospective seller, while expressly reserving

the ownership of the subject property despite its delivery

to the prospective buyer, commits to sell the property

exclusively to the prospective buyer upon fulfillment of

the condition agreed upon, i.e., full payment of the

purchase price. Full payment here is considered as a

positive suspensive condition.

As a result if the party contracting to sell, because of

non-compliance with the suspensive condition, seeks to

eject the prospective buyer from, the land, the seller is

enforcing the contract and is not resolving it. The failure

to pay is not a breach of contract but an event which

prevent the obligation to convey title from materializing.

Furthermore, the reservation of the title in the name of

Platinum Plans clearly indicates an intention of the

parties to enter into a contract to sell. Where the seller

promises to execute a deed of absolute sale upon

completion of the payment of purchase price, the

agreement is a contract to sell.

The court cannot, in this case, step in to cure the

deficiency by fixing the period pursuant to:

1.The relief sought by Cucueco was for specific

performance to compel Platinum Plans to receive the

balance of the purchase price.

2.The relief provide in Art 1592 only applies to contracts

of sale

3. Because of the differing dates set by both parties, the

court would have no basis for granting Cucueco an

extension of time within which to pay the outstanding

balance

SELLER CANNOT TREAT THE CONTRACT AS

CANCELLED WITHOUT SERVING NOTICE

The act of a party in treating the contract as cancelled

should be made known to the other party because this act

is subject to scrutiny and review by the courts in cased

the alleged defaulter brings the matter for judicial

determination as explained in UP v. De los Angeles. In

the case at bar, there were repeated written notices sent

by Platinum Plans to Cucueco that failure to pay the

balance would result in the cancellation of the contract

and forfeiture of the down payment already made. Under

these circumstance, the cancellation made by Platinum

Plans is valid and reasonable (except for the forfeiture of

the down payment because Cucueco never agreed to the

same)

EFFECTS OF CONTRACT TO SELL

In the present case, neither side was able to produce any

written evidence documenting the actual terms of their

agreement. The trial court was correct in finding that

there was no meeting of minds in this case considering

that the acceptance of the offer was not absolute and

uncondition. In earlier cases, the SC held that before a

valid and binding contract of sale can exist, the manner

of payment of the purchase price must first be

established.

A contract to sell would be rendered ineffective and

without force and effect by the non-fulfillment of the

buyers obligation to pay since this is a suspensive

condition to the obligation of the seller to sell and

deliver the title of the property. As an effect, the parties

stand as if the conditional obligation had never existed.

There can be no rescission of an obligation that is still

non-existent as the suspensive condition has not yet

occurred.

CAS RELIANCE ON LEVY

GERVACIO IS MISPLACED

HERMANOS

V.

It was unnecessary for CA to distinguish whether the

transaction between the parties was an installment sale

or a straight sale. In the first place, there is no valid and

enforceable contract to speak of.

REYNALDO VILLANUEVA, petitioner,

vs.

PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK

(PNB), respondent.

ISSUE: Whether a perfected contract of sale exists

between petitioner and respondent PNB

The Special Assets Management Department

(SAMD) of the Philippine National Bank (PNB)

issued an advertisement for the sale thru bidding of

certain PNB properties in Calumpang, General

Santos City, including Lot No. 17, covered by TCT

No. T-15042, consisting of 22,780 square meters,

with an advertised floor price ofP1,409,000.00, and

Lot No. 19, covered by TCT No. T-15036,

consisting of 41,190 square meters, with an

advertised floor price of P2,268,000.00. Bidding

was subject to the following conditions: 1) that cash

bids be submitted not later than April 27, 1989; 2)

that said bids be accompanied by a 10% deposit in

managers or cashiers check; and 3) that all

acceptable bids be subject to approval by PNB

authorities.

The defendant through Vice-President Guevara

negotiated with the plaintiff in connection with the

offer of the plaintiff to buy Lots 17 & 19. The offer of

plaintiff to buy, however, was accepted by the

defendant only insofar as Lot 19 is concerned as

exemplified by its letter dated July 6, 1990 where

the plaintiff signified his concurrence after

conferring with the defendants vice-president. The

conformity of the plaintiff was typewritten by the

defendants own people where the plaintiff

accepted the price of P2,883,300.00. The

defendant also issued a receipt to the plaintiff on

the same day when the plaintiff paid the amount

ofP200,000.00 to complete the downpayment

of P600,000.00. With this development, the plaintiff

was also given the go signal by the defendant to

improve Lot 19 because it was already in effect

sold to him and because of that the defendant

fenced the lot and completed his two houses on the

property.

G.R. No. 154493

December 6, 2006

On October 11, 1990, however, Guevara wrote

Villanueva that, upon orders of the PNB Board of

Directors to conduct another appraisal and public

bidding of Lot No. 19, SAMD is deferring

negotiations with him over said property and

returning his deposit of P580,000.00. Undaunted,

Villanueva attempted to deliver postdated checks

covering the balance of the purchase price but PNB

refused the same.

Villanueva filed with the RTC a Complaint

RTC: judgment is rendered in favor of the plaintiff.

The RTC anchored its judgment on the finding that

there existed a perfected contract of sale between

PNB and Villanueva. The RTC also pointed out that

Villanuevas P580,000.00

downpayment

was

actually in the nature of earnest money acceptance

of which by PNB signified that there was already a

sale.

PNB appealed to the CA: decision is reversed.

According to the CA, there was no perfected

contract of sale because the July 6, 1990 letter of

Guevara constituted a qualified acceptance of the

June 28, 1990 offer of Villanueva, and to which

Villanueva replied on July 11, 1990 with a modified

offer.

In the case at bench, consent, in respect to the

price and manner of its payment, is lacking. The

record shows that appellant, thru Guevaras July 6,

1990 letter, made a qualified acceptance of

appellees letter-offer dated June 28, 1990 by

imposing an asking price of P2,883,300.00 in cash

for Lot 19. The letter dated July 6, 1990 constituted

a counter-offer (Art. 1319, Civil Code), to which

appellee made a new proposal, i.e., to pay the

amount of P2,883,300.00 in staggered amounts,

that is, P600,000.00 as downpayment and the

balance within two years in quarterly amortizations.

Appellees new proposal, which constitutes a

counter-offer, was not accepted by appellant, its

board having decided to have Lot 19 reappraised

and sold thru public bidding.

Villanuevas motion for reconsideration is CA is

denied. Hence, petition to SC:

Court sustains CA on both issues.

Contracts of sale are perfected by mutual consent

whereby the seller obligates himself, for a price

certain, to deliver and transfer ownership of a

specified thing or right to the buyer over which the

latter agrees. Mutual consent being a state of mind,

its existence may only be inferred from the

confluence of two acts of the parties: an offer

certain as to the object of the contract and its

consideration, and an acceptance of the offer which

is absolute in that it refers to the exact object and

consideration embodied in said offer. While it is

impossible to expect the acceptance to echo every

nuance of the offer, it is imperative that it assents to

those points in the offer which, under the operative

facts of each contract, are not only material but

motivating as well. Anything short of that level of

mutuality produces not a contract but a mere

counter-offer

awaiting

acceptance. More

particularly on the matter of the consideration of the

contract, the offer and its acceptance must be

unanimous both on the rate of the payment and on

its term. An acceptance of an offer which agrees to

the rate but varies the term is ineffective.

From beginning to end, respondent denied that a

contract of sale with petitioner was ever perfected.

Its defense was broad enough to encompass every

issue relating to the concurrence of the elements of

contract, specifically on whether it consented to the

object of the sale and its consideration.

Acceptance of petitioners payments did not

amount to an implied acceptance of his last

counter-offer.

Moreover, petitioners payment of P200,000.00 was

with the clear understanding that his July 11, 1990

counter-offer was still subject to approval by

respondent. This is borne out by respondent, which

petitioner never controverted, where it appears on

the dorsal portion of O.R. No. 16997 that petitioner

acceded that the amount he paid was a mere "x x x

deposit made to show the sincerity of [his]

purchase offer with the understanding that it shall

be returned without interest if [his] offer is not

favorably considered x x x." This was a clear

acknowledgment on his part that there was yet no

perfected contract with respondent and that even

with the payments he had advanced, his July 11,

1990 counter-offer was still subject to consideration

by respondent.

In sum, the amounts paid by petitioner were not in

the nature of downpayment or earnest money but

were mere deposits or proof of his interest in the

purchase of Lot No. 19. Acceptance of said

amounts by respondent does not presuppose

perfection of any contract.

It must be noted that petitioner has expressly

admitted that he had withdrawn the entire amount

of P580,000.00 deposit from PNB-General Santos

Branch.

The petition is denied. The of the Court of Appeals

are AFFIRMED.

G.R. No. 166862 December 20, 2006

MANILA METAL CONTAINER CORPORATION,

petitioner,

REYNALDO C. TOLENTINO, intervenor,

vs.

PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, respondent,

DMCI-PROJECT DEVELOPERS, INC., intervenor.

ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner and respondent

PNB had entered into a perfected contract for

petitioner to repurchase the property from

respondent.

Petitioner was the owner of 8,015 square

meters of parcel of land located in Mandaluyong

City, Metro Manila. To secure a P900,000.00 loan it

had obtained from respondent Philippine National

Bank, petitioner executed a real estate mortgage

over the lot. Respondent PNB later granted

petitioner a new credit accommodation. On August

5, 1982, respondent PNB filed a petition for

extrajudicial foreclosure of the real estate mortgage

and sought to have the property sold at public

auction. After due notice and publication, the

property was sold at public action where

respondent PNB was declared the winning bidder.

Petitioner sent a letter to PNB, requesting it to be

granted an extension of time to redeem/repurchase

the property. Some PNB personnel informed that as

a matter of policy, the bank does not accept partial

redemption. Since petitioner failed to redeem the

property, the Register of Deeds cancelled TCT No.

32098 and issued a new title in favor of PNB.

Meanwhile, the Special Asset Management

Department (SAMD) had prepared a statement of

account of petitioners obligation. It also

recommended the management of PNB to allow

petitioner to repurchase the property for

P1,574,560.oo. PNB rejected the offer and

recommendation of SAMD. It instead suggested to

petitioner

to

purchase

the

property

for

P2,660,000.00, in its minimum market value.

Petitioner declared that it had already agreed to

SAMDs offer to purchase for P1,574,560.47 and

deposited a P725,000.00.

Petitioner, however, did not agree to

respondent PNB's proposal. PNB again informed

petitioner that it would return the deposit should

petitioner desire to withdraw its offer to purchase

the property. On June 4, 1985, respondent PNB

informed petitioner that the PNB Board of Directors

had accepted petitioner's offer to purchase the

property, but for P1,931,389.53 in cash less the

P725,000.00 already deposited with it.

PETITIONER: Petitioner rejected respondent's

proposal in a letter dated July 14, 1988. It

maintained that respondent PNB had agreed to sell

the property for P1,574,560.47, and that since its

P725,000.00 downpayment had been accepted,

respondent PNB was proscribed from increasing

the purchase price of the property.

RESPONDENT: it had acquired ownership over

the property after the period to redeem had

elapsed. It claimed that no contract of sale was

perfected between it and petitioner after the period

to redeem the property had expired.

RTC dismissed the complaint. It ordered

respondent PNB to refund the P725,000.00 deposit

petitioner had made. The trial court ruled that there

was no perfected contract of sale between the

parties; hence, petitioner had no cause of action for

specific performance against respondent. The trial

court declared that respondent had rejected

petitioner's offer to repurchase the property.

Petitioner, in turn, rejected the terms and conditions

contained in the June 4, 1985 letter of the SAMD.

While petitioner had offered to repurchase the

property per its letter of July 14, 1988, the amount

of P643,422.34 was way below the P1,206,389.53

which respondent PNB had demanded. It further

declared that the P725,000.00 remitted by

petitioner to respondent PNB on June 4, 1985 was

a "deposit," and not a downpayment or earnest

money.

Petitioner appealed in CA. CA affirmed the decision

of RTC. It declared that petitioner obviously never

agreed to the selling price proposed by respondent

PNB (P1,931,389.53) since petitioner had kept on

insisting that the selling price should be lowered to

P1,574,560.47. Clearly therefore, there was no

meeting of the minds between the parties as to the

price or consideration of the sale.

The CA ratiocinated that petitioner's original offer to

purchase the subject property had not been

accepted by respondent PNB. In fact, it made a

counter-offer through its June 4, 1985 letter

specifically on the selling price; petitioner did not

agree to the counter-offer; and the negotiations did

not prosper. Moreover, petitioner did not pay the

balance of the purchase price within the sixty-day

period set in the June 4, 1985 letter of respondent

PNB. Consequently, there was no perfected

contract of sale, and as such, there was no contract

to rescind.

Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration, which the

CA likewise denied.

Thus, petitioner filed the instant petition for review on

certiorari.

PETITIONER: Petitioner posits that respondent was

proscribed from increasing the interest rate after it had

accepted respondent's offer to sell the property for

P1,574,560.00. Consequently, respondent could no

longer validly make a counter-offer of P1,931,789.88 for

the purchase of the property. It likewise maintains that,

although the P725,000.00 was considered as "deposit for

the repurchase of the property" in the receipt issued by

the SAMD, the amount constitutes earnest money.

RESPONDENT: respondent contends that the parties

never graduated from the "negotiation stage" as they

could not agree on the amount of the repurchase price of

the property. the Statement of Account prepared by

SAMD as of June 25, 1984 cannot be classified as a

counter-offer; it is simply a recital of its total monetary

claims against petitioner.

Ruling:

The SC affirmed the ruling of the appellate

court that there was no perfected contact of sale

between the parties.

A contract is meeting of minds between two

persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to

the other, to give something or to render some

service. Under 1818 of the Civil Code, there is no

contract unless the following requisites concur:

Contract is perfected by mere consent which is

manifested by the meeting of the offer and the

acceptance upon the thing and causes which are to

constitute the contract. Once perfected, the bind

between other contracting parties and the

obligations arising therefrom have the form of law

between the parties and should be complied in

good faith. The absence of any essential element

will negate the existence of a perfected contract of

sale.

The court ruled in Boston Bank of the

Philippines vs Manalo:

A definite agreement as to the price is an

essential element of a binding agreement to sell

personal or real property because it seriously

affects the rights and obligations of the parties.

Price is an essential element in the formation of a

binding and enforceable contract of sale. The fixing

of the price can never be left to the decision of one

of the contracting parties. But a price fixed by one