Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Breadth of Receptive Vocabulary Knowledge Among English Major University Students JONUS

Încărcat de

Mahani MohamadTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Breadth of Receptive Vocabulary Knowledge Among English Major University Students JONUS

Încărcat de

Mahani MohamadDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press)

ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

Journal of Nusantara

Studies (JONUS)

THE BREADTH OF RECEPTIVE VOCABULARY KNOWLEDGE AMONG

ENGLISH MAJOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS

*1

1,2

Kamariah Yunus, 2Mahani Mohamed, 3Bordin Waelateh

Centre of English Language Studies, Faculty of Languages and Communication, Universiti

Sultan Zainal Abidin, Gong Badak Campus, 21300 Kuala Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia

3

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Prince Songkla University, Pattani, Thailand

*Corresponding author: kamariah@unisza.edu.my

ABSTRACT

Vocabulary knowledge is a key component for literacy skills as well as the development of

communication deemed important for students to succeed in university. Gaining adequate receptive

vocabulary knowledge would enhance a university students comprehension of academic texts. This

descriptive study aims to investigate the receptive vocabulary knowledge among English major

university students in Malaysia and Thailand. The sample comprises 80 English major students from

Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Malaysia and 86 English major students from Prince

Songkla University (PSU), Thailand. A Vocabulary Size Test (VST) adopted from Nation and Beglar

was employed to gather the primary data from the respondents about their receptive vocabulary

knowledge. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 was used for data analysis.

Results showed that, on average, UniSZA students had a higher VST score (44.64%) compared to that

of PSU students (20.92%). The higher average score gained by UniSZA students was mainly due to

early exposure to formal English education in schools. This study recommends preparing students with

explicit academic vocabulary instruction, particularly in the beginning semester of an English

programme, to meet the academic and professional needs of English major students in future.

Keywords: Receptive vocabulary, productive vocabulary, Vocabulary Size Test (VST), breadth of

vocabulary knowledge, depth of vocabulary knowledge.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

In this globalised era, possessing a strong English vocabulary is very essential for successful

communication worldwide. Modern English communication requires both the receptive and

productive vocabulary to be acquired by non-native speakers because these two types of

vocabulary will enable them to write and communicate efficiently.

Vocabulary knowledge is fundamental to effective communication (Nation, 2001),

especially among university students. This is especially true when English as Second Language

Learners (ESL) are often required to read academic books written in English, and to express

themselves verbally in the language (e.g., giving presentation) or when writing (e.g.,

assignments). It is therefore important pedagogically to know the receptive and productive

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

knowledge of the students as a means of gauging the vocabulary threshold level needed for

academic survival in university.

2.0 LITERATURE REVIEW

Vocabulary knowledge involves knowing the many aspects of words. It involves knowing the

tokens (number of words, e.g., five in The man entertained the elephant.), types (number of

different words, e.g., four different words (underlined) in The man entertained the elephant. by

excluding one the), lemma (a headword and its most frequent inflection, e.g., entertains,

entertained, and entertaining are the lemma of the verb but not entertainment as it is a noun),

and word family (different words with various parts of speech, for example, entertain,

entertaining, and entertainers). Nation (2001) itemised nine different types of knowledge that

are required to know a word including; knowledge of the spoken form of a word, knowledge

of the written form of a word, knowledge of the parts in a word which has meaning, knowledge

of the link between a particular form and a meaning, knowledge of the concepts a word may

possess and the items it can refer to, knowledge of the vocabulary that is associated with a

word, knowledge of a word's grammatical functions, knowledge of a words collocations, and

lastly, knowledge of a word's register and frequency. In other words, vocabulary knowledge is

not a chaotic system but rather an organised system in which various types of knowledge are

learned until all aspects of knowledge are known for an item (Moghadam, Zainal, &

Ghaderpour, 2012, p. 557).

Nation (2001) also broke down each aspect of the word knowledge into receptive and

productive knowledge. Receptive (passive) vocabulary knowledge is defined as the knowledge

of the form (the ability to understand a word while listening or reading), while productive

(active) vocabulary knowledge is the use (the ability to use a word in speaking or writing).

Passive vocabulary knowledge involves perceiving the form of a word while listening or

reading and retrieving its meaning (language input). Productive vocabulary knowledge, on the

other hand, expresses a meaning through speaking or writing, retrieving and producing the

appropriate spoken or written word form (language output). Thus, passive vocabulary

knowledge involves a process from form to meaning while productive vocabulary knowledge

involves a process from meaning to form. Receptive vocabulary is known as the breadth of

vocabulary size while productive vocabulary is the depth of vocabulary knowledge (Nation,

2001; Qian, 2002). Basically, receptive vocabulary is twice the size of productive vocabulary

(Cobb, 1997; Schmitt, 2008). The breadth of vocabulary knowledge is basically the number of

words for which a learner has at least the minimum knowledge of meaning (Qian, 1999; 2000).

The minimum knowledge of a words meaning is defined as a students ability to recognise its

most frequent meaning.

Receptive vocabulary plays a main role in increasing a learners vocabulary knowledge.

Receptive vocabulary is stored in our mental lexicon to be used when needed productively. It

is very essential since a learner who has larger receptive vocabulary is likely to know more

words productively than does a learner who has a smaller receptive vocabulary (Webb, 2008).

Besides, when vocabulary is taught in the classroom, learning is also likely to be receptive

(Webb, 2005). In other words, vocabulary learning tasks are more likely to be receptive than

productive.

Students who major in English must have extensive vocabulary knowledge for the

development of literacy skills and communication in the academic world. Researchers have

estimated that ESL learners need to know about 2,000 of the most frequently-used words to

successfully communicate in basic everyday life conversations and to prepare for more

8

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

advanced study (Schmitt, 2000, p. 142). Schmitt and Schmitt (2014) proposed to raise this

threshold to the 3,000 most frequent words in English in order to include additional words that

provide a significant coverage of the English lexicon. Meanwhile, Laufer (1997, p.114)

mentions that a text coverage of 95% can be reached with a 5,000-word English vocabulary

or 3,000 word families. However, Nation (2006) contends that in order for a university student

to understand a written text, he or she will need to acquire approximately 8,000 word families.

This constitutes reaching the threshold of 2,000-3,000 high-frequency words plus 570 word

families listed in the Coxheads (2002) Academic Word List (AWL).

Francis and Kucera (1982) claimed that having a large vocabulary size is very important

for university students since there is a strong relationship between the effect of vocabulary size

and text coverage. This indicates that the number of words stored in university students mental

lexicon may affect their comprehension of academic texts. The two researchers listed the

vocabulary size and equivalent written text coverage for easy reference in Table 1. The table

shows that if a student is familiar with the words at the highest frequency level (the first 1,000),

they will have 72 percent of text coverage. In addition, if a learner has a vocabulary size of

2,000 word families, the learner will have 80 percent of text coverage, which means that one

word in every five words (approximately two words in every line) are unknown (Nation &

Waring, 1997).

Table 1: Vocabulary size and text coverage in the Brown Corpus

Vocabulary Size

Written Text Coverage

1,000

72.0%

2,000

79.7%

3,000

84.0%

4,000

86.8%

5,000

88.7%

6,000

89.9%

8,000 and above

97.8%

Goulden, Nation, and Read (1990) have estimated the receptive vocabulary size of

university-educated native speakers of English. This figure must be achievable by universityeducated non-native speakers of English for successful academic textbook comprehension and

fulfilling all of academic tasks. The researchers claim that the receptive vocabulary size range

of university-educated native English speakers is between 13,200 to 20,700 base words with

an average of 17,200 base words. Based on this statistics, it is evident that university-educated

non-native English speakers should reach approximately 17,000 word families, and this is

equivalent to the range between 13,500 and 20,000 base words. Besides, if independent

comprehension is based on knowing 98% of the running words in a text, then L2 learners need

a range of 8000 to 9000 word-family vocabulary for comprehension of written text, such as

those in newspapers and novels, and a vocabulary range of 6,000 to 7,000 for spoken texts such

as lectures and movies (Nation 2006).

Table 2: Vocabulary sizes needed to get 98% coverage or independent comprehension

(adapted from Nation, 2006)

Texts

98% coverage

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

Novels

9,000 word families

Newspapers

8,000 word families

Childrens movies

6,000 word families

Spoken English

Academic/ Specialised/Technical texts

in higher institutions

7,000 word families

8,000 to 20,000 word families

However, achieving adequate receptive vocabulary size has still become one of the

biggest obstacles faced by many ESL learners (Nation, 2006). Even though ESL or English as

a foreign language (EFL) learners were found to have spent years studying English, their

vocabulary size is much less than 5,000 word-families (Nation, 2006; Mokhtar, 2010; Alkhofi,

2015; Hajiyeva, 2015). This is considered far from reaching the threshold of vocabulary size

expected of a university student; that is, the 98% threshold of 8,000 word families as claimed

by Laufer and RavenhorstKalovski (2010) for text comprehension. The same phenomenon was

also observed in the ESL students who major in English in the Faculty of Languages and

Communication (FBK), UniSZA, Malaysia and the English major EFL learners in the Faculty

of Humanities and Social Sciences (HUSO), Prince Songkla University (PSU), Pattani,

Thailand. Many were observed to have insufficient receptive and productive vocabulary sizes

expected of them as evident in their average grades achieved in the reading comprehension and

writing tests.

Acquiring vocabulary and gaining sufficient vocabulary size has often become a

stumbling block to some students due to several discerning factors including learning disability,

lack of exposure to English, lack of self-confidence, and lack of knowledge about the right

vocabulary strategies. Even though many studies focused on investigating the receptive

vocabulary size of university students in all majors and academic degrees in many countries

including Malaysia and Thailand (see Sripetpun, 2000; Mokhtar, 2010; Zhang & Lu, 2013;

Nirattisai & Chiramanee, 2014), and comparing receptive vocabulary knowledge between

native and non-native speakers (Hajiyeva, 2015), or measuring the receptive vocabulary

knowledge of EFL learners from two different universities (Zhiying, Teo, & Laohawiriyanon,

2007), very little work has focused on comparing receptive vocabulary knowledge between

ESL freshmen and EFL freshmen in two different universities. It is the aim of this paper

therefore to compare the receptive vocabulary knowledge of the first year and first semester

English major students from the two English language faculties the freshmen (ESL learners)

from the Faculty of Languages and Communication (FBK) UniSZA, Malaysia and the

freshmen (EFL learners) from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HUSO), Prince

Songkla University (PSU), Pattani, Thailand.

3.0 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This section explains the methods and data analysis used in the study.

3.1 Research Design and Sample

This study is designed as a descriptive study. The study population was the English major

students from the Faculty of Languages and Communication (FBK), Universiti Sultan Zainal

Abidin (UniSZA), Malaysia and the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science (HUSO), Prince

Songkla University (PSU), Pattani, Thailand. The sample was purposively selected from 80

freshmen (first year and first semester students from FBK) and 89 freshmen (first year and first

semester students from HUSO). The age range of FBK students was from 20 to 21 and HUSO

from 19 to 20. In terms of gender, 15 male students from FBK and 19 male freshmen from

10

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

HUSO participated in this study, in contrast to 65 and 70 female freshmen from the faculties

consecutively. Meanwhile, in terms of schooling, FBK students had longer formal English

education (M=14.1) compared to the freshmen from HUSO (M=11.1). Table 3 below presents

demographic information of the participants.

Table 3: Demographic information about the participants at FBK and PSU

*Years Studying

Age

Gender

English

Mean (year)

Male

Female

Mean (year)

FBK students (n=80)

20.1

15

65

14.1

HUSO students (n=89)

19.6

19

70

11.1

*All students had been taught by English teachers from their own countries.

3.2 Research Instrument and Procedures

Nation (2001) and Webb (2009) argue that vocabulary size can be measured based on three

important criteria - tokens, types, and word family. Tokens are each running word, literally all

the words in a given text or sentence. On the other hand, types are all the different words in a

text. Unlike types, word family comprises the headword (e.g., care) and all its derived forms

(e.g., careful, cared, carefully) which seems more rational as compared to counting types or

tokens in assessing a learner vocabulary size (Nation & Webb, 2011). Nation and Webb (2011)

also maintain that counting all words in the same word family as one single word in order to

give an estimate of ones vocabulary size seems to be the most accurate method for this

purpose. There have been many vocabulary size tests designed to date to measure students

receptive and productive vocabulary sizes (see Meara, 1992; Laufer & Nation, 1999; Nation &

Beglar, 2007; Cobb, 2010). Different researchers recommend different vocabulary tests

depending on their view of vocabulary knowledge, their preference for a particular dimension

or modality of vocabulary knowledge, and their interest in either size, depth or strength

(Laufer & Goldstein, 2004).

This study aims to investigate students receptive vocabulary knowledge. Nation and

Beglars (2007) Receptive Vocabulary Size Test (14,000 version) was employed to measure

the freshmens level of receptive vocabulary. The original test comprises 140 multiple choice

items. However, only 100 items were included in this study, in which the items from 10,000 to

14,000 word level were not accounted for. The test was designed to measure the participants

written receptive vocabulary size in English. There are 10 items from each 1,000 word family

level. The VLT provides a vocabulary learning profile by utilizing knowledge at five levels the 2,000, 3,000, 5,000 and 10,000 frequency levels, as well as a section on academic

vocabulary, based on the Academic Word List (Schmitt, Schmitt, & Clapham, 2001). The

vocabulary knowledge is tested by a selection of representative words (nouns, verbs and

adjectives) from each of the five levels, where the test-takers are asked to match words to the

correct descriptions.

In terms of procedure, the same test was carried out in two different locations (FBK,

UniSZA, Malaysia and HUSO, PSU, Thailand), at a different time, and by different authorities.

The test was administered to 80 FBK freshmen a month after they registered as students at

11

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

UniSZA, Malaysia (in October, 2015). The students took the test during a class taught by one

of the studys researchers. They were given one and a half hours to complete the test. The

researcher from HUSO conducted the test separately with the 89 participants in midSeptember, 2015 in Thailand. The duration of the test, however, was held constant. A brief

introduction of the research was given to the participants before the test was started. In order

to maintain the validity and reliability of the test, the participants were not allowed to share

information with one another. After the test items were collected, data were run separately by

the two sets of researchers using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 21.0. Data

were analysed in percentages and mean. In order to find the participants total vocabulary size,

the total score was multiplied by 100.

4.0 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study aims to compare the receptive vocabulary knowledge of the first year and first

semester English major students from two English language faculties the Faculty of

Languages and Communication (FBK) UniSZA, Malaysia and the Faculty of Humanities and

Social Science (HUSO), Prince Songkla University (PSU), Pattani, Thailand. Table 4 presents

the Vocabulary Size Range (VST) scores of the freshmen from the two faculties. The results

indicate that out of 100 items, the lowest VST range obtained by the FBK freshmen was 26, in

contrast to seven VST range obtained by the freshmen of HUSO, PSU. The table also showed

that the highest VST score (68) was obtained by the FBK freshmen compared to 52 VST score

achieved by their HUSO counterparts. On average, the FBK freshmen achieved raw VST score

of 44.6 compared to 20.9 by the HUSO freshmen.

Table 4: VST range (raw score per 100)

Score

FBK, UniSZA

HUSO, PSU

Lowest

26

Highest

68

52

Average

44.6

20.9

The fact that the FBK freshmen performed better than the HUSO freshmen in the VST

can be explained in terms of the emphasis given by the Malaysian government to improve the

level of English language proficiency among Malaysians, and the status given to English as a

second language in Malaysia. English is regarded as the second important language to be

acquired by Malaysian students after Bahasa Melayu (the national language). It is a language

frequently spoken by many Malaysians working in employment sectors such as the courts,

higher learning institutions, and business. Even though its status is secondary to Bahasa

Melayu, the role that English plays as a globalised and commercial language is immense. The

need to improve English language competence among Malaysian university students is

therefore urgent. The Ministry of Education of Malaysia (KPM) has placed a greater emphasis

on English listening and speaking components in the English language syllabus of the primary

and secondary schools in Malaysia.

Another explanation to the higher VST score gained by the FBK freshmen is the daily

exposure to English conversations in the Malaysian environment. English is a language spoken

in almost every Malaysian household, especially those on the west coast of the country. It is

language that many Malaysians use every day to communicate with their spouse, relatives,

neighbours as well as with colleagues at the workplace.

12

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

In terms of education, the FBK freshmen had spent more than 12 years learning English

in school. This formal English schooling and also a high English entry qualification for

admission into FBK (a Malaysian University English Test (MUET) Band Four) are the reasons

for the higher VST score achieved by the FBK freshmen. For many decades, KPM has made it

compulsory for all Malaysian citizens at pre, primary, and secondary school levels to be given

formal English language education. The long exposure is adequate for providing opportunities

for Malaysian freshmen students to practice English, and this has resulted in an increased size

of receptive vocabulary knowledge (Mokhtar, 2010; Mokhtar, Rawian, Yahaya, Abdullah, &

Mohamed, 2008).

In contrary to the heavy emphasis given by the Malaysian government to increase the

use of English in Malaysia, the language is, unfortunately, viewed as foreign in Thailand.

English is not a language spoken frequently by the Thai people at the workplace or households.

In Thailand, limited knowledge of English vocabulary is one of the major problems for students

learning English at the tertiary level, and this inhibits their success in the academic programmes

(Rattanavich, 2013). Historically, Thailand was never colonialized by any foreign power, and

this is the reason why the country is predominantly monolingual. English is not a lingua franca

used in any activity in the country especially in schools and higher learning institutions

(Rattanavich, 2013). At the same time, a lower English entry qualification requirement into the

Bachelor of Arts (English) programme at HUSO is also a factor for the lower VST score.

Table 5 present the VST scores of both sets of freshmen based on the VST level (1,000

to 10,000 word families). It can be observed that FBK freshmen outperformed HUSO

freshmen in terms of vocabulary size. The VS of FBK freshmen ranged from 3,000 (lowest) to

8,000 (highest), in contrast to a range of 1,000 (lowest) to 7,000 (highest) scored by PSU

freshmen.

Table 5: A comparison of VST scores of the FBK and PSU freshmen

FBK, UniSZA

HUSO, PSU

Score

Number of Students (%)

Number of Students (%)

1000 to 2000

8 (8.9%)

2000 to 3000

38 (42.7%)

3000 to 4000

1 (1.25%)

32 (35.9%)

4000 to 5000

29 (36.3%)

4 (4.5%)

5000 to 6000

31 (38.8%)

5 (5.6%)

6000 to 7000

16 (20%)

2 (2.24%)

7000 to 8000

3 (3.75%)

8000 to 10000

10000 to 14000

not tested

not tested

Table 5 shows that FBK freshmen possessed more receptive word knowledge than

HUSO freshmen. Many had a lexical threshold level of 5,000 to 6,000 word level (31 or

38.8%). A lexical threshold level of 5,000 to 6,000 indicates the text coverage of 95% (Nation

& Beglar, 2007), which potentially means that the FBK freshmen had acquired more than

adequate lexical threshold for text comprehension. On the other hand, the results showed that

a majority of the HUSO freshmen had a lexical threshold level ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 (38

or 42.7 %). Only 2 (2.24%) of the HUSO freshmen had the receptive vocabulary knowledge of

13

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

6,000 to 7,000 word families. The 2,000 to 3,000 word level and 3,000 to 4,000 word level are

considered as barely adequate for academic text comprehension because they only indicate a

text coverage of 80% (Hu & Nation, 2000); Nation, 2006; Saigh & Schmitt, 2012; Laufer,

2013; Schmitt & Schmitt, 2014). This threshold level only indicates text comprehension of

simplified texts but not the unabridged ones (Hirsh & Nation, 1992; Schmitt, 2011). A

freshman must be equipped with a 5,000 word level in order to comprehend unsimplified texts

for reading for pleasure (e.g. novels). This threshold level is far from the optimal level

necessary for meeting the academic needs of the freshmen in HUSO, i.e., 8,000 to 20,000 word

level, including the level which has included the 570 academic word list (Coxhead, 2002), and

for comprehending academic texts without assistance. This study, therefore, concludes that the

HUSO freshmen possessed insufficient receptive vocabulary knowledge crucial for survival in

an academic world, particularly in undertaking English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses

in the beginning semesters.

Even though the results showed that FBK freshmen were superior to the HUSO

freshmen in the VST scores, it was also evident that they had also not yet achieved the optimal

threshold level (8,000 to 10,000 words), which is the threshold essential for successful

comprehension in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses (Laufer, 2013). Even though

possessing a 5,000 word level has been claimed as being sufficient for adequate comprehension

of all types of texts as it provides the reader with 95% text coverage (see Nation, 2006), the

level is still considered far from reaching full comprehension of academic and technical texts

(Laufer & Ravenhorst-Kalovski, 2010) used by college and university students. The optimal

threshold for EAP is set at 8,000 word families, which can be defined as can read academic

material independently and functional independence in reading (p. 25). Only three out of

the 80 FBK freshmen were in the 8,000 word level, with none from HUSO reaching that mark.

Several conclusions can be made to the reasons why freshmen from both FBK and

HUSO have not yet reached the optimal threshold level. One explanation is that both sets of

freshmen were first year first year and first semester students, thus were very new at their

respective faculties. The courses that they were taking when this study was conducted were

mainly elementary English courses, and this explains their lack of exposure to academic and

technical vocabulary.

The second reason is due to an absence of explicit academic or specialised vocabulary

instruction set up for actively teaching the words in the beginning semester of the Bachelor of

English with Communication programme offered by FBK, UniSZA, Malaysia and Bachelor of

Arts (English) programme offered by HUSO, PSU, Thailand. Even though some of the

English-related courses were included in both English programmes, the focus was mainly on

teaching advanced English skills (reading and writing) and subject-related courses with little

attention given to improving students receptive academic vocabulary knowledge, particularly

on exercising the 8,000 to 14,000 word level vocabulary.

5.0 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, reaching the optimal threshold level is deemed important and urgent for

university students as this receptive vocabulary knowledge may determine their success in the

academic world. Reading for university students involves comprehending specialised

terminologies and contents of subject-related books and research articles, whereby they must

perform these tasks unassisted at all time (Baumann, Kameenui, & Ash, 2003). Academic

success is closely related to the ability to read, and this relationship is logical because, in order

to understand what they have read, the students must have also a huge vocabulary. Students

14

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

who do not have large vocabularies often struggle to achieve comprehension. If this happens,

they will become frustrated and this feeling can continue throughout their studies. The ability

to comprehend academic texts proficiently and critically is a skill that all university students

must master in order to graduate, pursue post-graduate learning opportunities, and secure future

employment (Huddle, 2014). This study recommends the inclusion of an academic or

specialised vocabulary course in the English programmes in the two faculties as well as

equipping English lecturers with advanced vocabulary instructional methods for future

advancement of the programme and their learners academic progress.

REFERENCES

Alkhofi, A. (2015). Comparing the receptive vocabulary knowledge of intermediate-level

students of different native languages in an intensive English program (Unpublished

masters thesis), University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida.

Baumann J., Kame'enui, E., & Ash, G. (2003). Research on vocabulary instruction: Voltaire

redux. In Flood J., Lapp D., Squire J., Jensen J. (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching

the English language arts (2nd ed., pp. 752785). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cobb, T. (1997). Is there any measurable learning from hands-on concordancing? System,

25(3), 301-315.

Cobb, T. (2010). Learning about language and learners from computer programs. Reading in a

Foreign Language, 22(1), 181200.

Coxhead, A. (2002). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 213238.

Francis, W. N., & Kucera, H. (19820. Frequency analysis of English usage. New York:

Houghton Mifflin.

Hajiyeva, K. (2015). Exploring the relationship between receptive and productive vocabulary

sizes and their increased use by Azerbaijani English majors. English Language Teaching,

8 (8), 31-45.

Goulden, R., Nation, I.S.P., & Read, J. (1990). How large can a receptive vocabulary be?

Applied Linguistics, 11(4), 341-363.

Hirsh, D., & Nation, P. (1992). What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for

pleasure? Reading in a Foreign Language, 8, 689 - 696.

Hu, M., & Nation, I. S. P. (2000). Vocabulary density and reading comprehension. Reading in

a Foreign Language, 23, 403 - 430.

Huddle, S. M. (2014). The impact of fluency and vocabulary instruction on the reading

achievement of adolescent English language learners with reading disabilities. (Doctoral

thesis, University of Iowa). Retrieved from http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/4650

Laufer, B. & Goldstein, Z. (2004). Testing vocabulary knowledge: size, strength, and computer

adaptiveness. Language Learning, 53(3), 399-436.

Laufer, B., & Nation, P. (1999). A vocabulary-size test of controlled productive ability.

Language Testing, 16, 33 - 51.

15

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

Laufer, B., & Ravenhorst-Kalovski, G.C. (2010) Lexical threshold revisited: Lexical text

coverage, learners vocabulary size and reading comprehension. Reading in a Foreign

Language, 22(1), 15-30.

Laufer, B. (2013). Lexical thresholds for reading comprehension: What they are and how they

can be used for teaching purposes, Tesol Quarterly, 47(4), 867-872.

Meara, P. (1992). EFL vocabulary tests (1st ed.). Swansea: Centre for Applied Language

Studies, University College Swansea.

Moghadam, S. H., Zainal, Z. & Ghaderpour, M. (2012). A review on the important role of

vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension performance, Procedia Social and

Behavioural Sciences, 66, 555-563.

Mokhtar, A.A. (2010). Achieving native-like english lexical knowledge: The non-native story,

Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 1(4), 343-352.

Mokhtar, A. A., Rawian, R. M., Yahaya, M. F., Abdullah, A., & Mohamed, A. R. (2008).

Vocabulary learning strategies of adult ESL learners. The English Teacher XXXVIII,

133-145.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Nation, I.S.P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? Canadian

Modern Language Review, 63, 1, 59-82.

Nation, I.S.P., & Beglar, D. (2007). A vocabulary size test, The Language Teacher, 31(7), 913.

Nation, I.S.P., & Waring, R. (1997). Vocabulary size, text coverage, and word lists. In N.

Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp.

6-19). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I.S.P., & Webb, S. (2011). Researching and analyzing vocabulary. Boston, MA:

Heinle.

Nirattisai, S., & Chiramanee, T. (2014). Vocabulary learning strategies of Thai university

students and its relationship to vocabulary size, International Journal of English

Language Education, 2(1), 273-287.

Qian, D. (1999). Assessing the roles of depth and breadth of vocabulary knowledge in reading

comprehension. Canadian Modern Language Review , 56(2), 282308.

Qian, D. (2002). Investigating the relationship between vocabulary and academic reading

performance: An assessment perspective. Language Learning, 52, 513-536.

Rattanavich, S. (2013). Comparison of effects of teaching English to Thai undergraduate

teacher-students through cross-curricular thematic instruction program based on multiple

intelligence theory and conventional instruction. English Language Teaching, 6(9), 1-18.

Saigh, K. & Schmitt, N. (2012). Difficulties with vocabulary form: The case of Arabic ESL

learners. System, 40, 24-36.

16

Journal of Nusantara Studies 2016, Vol 1(1) 7-17

ISSN 0127-9319 (Press) ISSN 0127-9386 (Online)

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching

Research, 12, 329 363.

Schmitt, N., Schmitt, D., & Clapham, C. (2001). Developing and exploring the behaviour of

two new versions of the Vocabulary Levels Test. Language Testing, 18(1), 55-88.

Schmitt, N. & Schmitt, D. (2014). A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2

vocabulary teaching. Language Teaching, 47(4), 484-503.

Sripetpun, W. (2000). The influence of vocabulary size on vocabulary learning strategies and

vocabulary learning strategies. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. Victoria: La Trobe

University, Australia.

Webb, S. (2005). Receptive and productive vocabulary learning: The effects of reading and

writing on word knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(1), 33-52.

Webb, S. (2008). Receptive and productive vocabulary sizes of L2 learners. Studies in Second

Language Acquisition, 30(1), 79-95.

Webb, S. (2009). The effects of receptive and productive learning of word pairs on vocabulary

knowledge. RELC Journal, 40(3), 360-376.

Zhang, X., & Xiaofei, L. (2013). A longitudinal study of receptive vocabulary breadth

knowledge growth and vocabulary fluency development. Applied Linguistics, 1-23. doi:

10.1093/applin/amt014

Zhiying, Z., Teo, A., & Laohawiriyanon, C. (2007). A comparative study of passive and active

vocabulary knowledge of Prince of Songkla University and South China Agricultural

University EFL learners. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 3(1), 2550.

17

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Aman Multimedia LessonDocument20 paginiAman Multimedia LessonMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reverse Diabetes with Diet DNDDocument1 paginăReverse Diabetes with Diet DNDMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of QuestionDocument5 paginiTypes of QuestionMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Simulation Program - ESP Phase II ContinuationDocument67 paginiEnglish Simulation Program - ESP Phase II ContinuationMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reverse Diabetes with Diet DNDDocument1 paginăReverse Diabetes with Diet DNDMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- FBK Theme Book BM Cover - PNGDocument2 paginiFBK Theme Book BM Cover - PNGMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Simulation Program - ESP Phase II ContinuationDocument67 paginiEnglish Simulation Program - ESP Phase II ContinuationMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creative Commons Flickr Photos for PresentationsDocument8 paginiCreative Commons Flickr Photos for PresentationsMahani MohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Criminal Evidence Course OutlineDocument3 paginiCriminal Evidence Course OutlineChivas Gocela Dulguime100% (1)

- Application of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisDocument21 paginiApplication of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisAdrian NavarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexDocument3 paginiAssignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexNauman MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Ulangan Harian Smester 1 Kelas 8 SMP BAHASA INGGRISDocument59 paginiSoal Ulangan Harian Smester 1 Kelas 8 SMP BAHASA INGGRISsdn6waykhilauÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHP - 3 DatabaseDocument5 paginiCHP - 3 DatabaseNway Nway Wint AungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chrome Settings For CameraDocument6 paginiChrome Settings For CameraDeep BhanushaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rescue FindingsDocument8 paginiThe Rescue FindingsBini Tugma Bini Tugma100% (1)

- Remnan TIIDocument68 paginiRemnan TIIJOSE MIGUEL SARABIAÎncă nu există evaluări

- It - Unit 14 - Assignment 2 1Document8 paginiIt - Unit 14 - Assignment 2 1api-669143014Încă nu există evaluări

- Modification of Core Beliefs in Cognitive TherapyDocument19 paginiModification of Core Beliefs in Cognitive TherapysalalepeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performance Requirements For Organic Coatings Applied To Under Hood and Chassis ComponentsDocument31 paginiPerformance Requirements For Organic Coatings Applied To Under Hood and Chassis ComponentsIBR100% (2)

- Ds B2B Data Trans 7027Document4 paginiDs B2B Data Trans 7027Shipra SriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evoe Spring Spa Targeting Climbers with Affordable WellnessDocument7 paginiEvoe Spring Spa Targeting Climbers with Affordable WellnessKenny AlphaÎncă nu există evaluări

- First State of The Nation Address of ArroyoDocument9 paginiFirst State of The Nation Address of ArroyoJennifer Sisperez Buraga-Waña LptÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOG 5 Topics With SOPDocument2 paginiSOG 5 Topics With SOPMae Ann VillasÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Empirical Study of Car Selection Factors - A Qualitative & Systematic Review of LiteratureDocument15 paginiAn Empirical Study of Car Selection Factors - A Qualitative & Systematic Review of LiteratureadhbawaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boeing 7E7 - UV6426-XLS-ENGDocument85 paginiBoeing 7E7 - UV6426-XLS-ENGjk kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSP, Modern Technologies and Large Scale PDFDocument11 paginiPSP, Modern Technologies and Large Scale PDFDeepak GehlotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limiting and Excess Reactants Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiLimiting and Excess Reactants Lesson Planapi-316338270100% (3)

- Mendoza CasesDocument66 paginiMendoza Casespoiuytrewq9115Încă nu există evaluări

- Madagascar's Unique Wildlife in DangerDocument2 paginiMadagascar's Unique Wildlife in DangerfranciscogarridoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding key abdominal anatomy termsDocument125 paginiUnderstanding key abdominal anatomy termscassandroskomplexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Junior Instructor (Computer Operator & Programming Assistant) - Kerala PSC Blog - PSC Exam Questions and AnswersDocument13 paginiJunior Instructor (Computer Operator & Programming Assistant) - Kerala PSC Blog - PSC Exam Questions and AnswersDrAjay Singh100% (1)

- Certificate of Compliance ATF F 5330 20Document2 paginiCertificate of Compliance ATF F 5330 20Jojo Aboyme CorcillesÎncă nu există evaluări

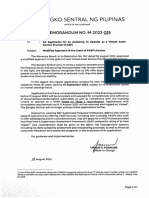

- BSP Memorandum No. M-2022-035Document1 paginăBSP Memorandum No. M-2022-035Gleim Brean EranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Conflict With Slavery and Others, Complete, Volume VII, The Works of Whittier: The Conflict With Slavery, Politicsand Reform, The Inner Life and Criticism by Whittier, John Greenleaf, 1807-1892Document180 paginiThe Conflict With Slavery and Others, Complete, Volume VII, The Works of Whittier: The Conflict With Slavery, Politicsand Reform, The Inner Life and Criticism by Whittier, John Greenleaf, 1807-1892Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- EDU101 Solution FileDocument2 paginiEDU101 Solution FileTahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metabolic Pathway of Carbohydrate and GlycolysisDocument22 paginiMetabolic Pathway of Carbohydrate and GlycolysisDarshansinh MahidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors of Cloud ComputingDocument19 paginiFactors of Cloud ComputingAdarsh TiwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Notes - Sedimentation TankDocument45 paginiLecture Notes - Sedimentation TankJomer Levi PortuguezÎncă nu există evaluări