Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Quarterly, Focusing Specifically On Issues Published Between 1977 and 1979. I Chose These

Încărcat de

Shewit Sereke ZeraiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Quarterly, Focusing Specifically On Issues Published Between 1977 and 1979. I Chose These

Încărcat de

Shewit Sereke ZeraiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Shewit S.

Zerai

Journal Review

April 20th, 2015

I studied three journals, Korean Studies, The Journal of Japanese Studies and The China

Quarterly, focusing specifically on issues published between 1977 and 1979. I chose these

journals and this time period because I wanted a more diverse representation of East Asian

journals, but also some thread of commonality. While all the journals have a somewhat similar

format and writing style, each journal brought a unique presentation of historical analysis,

quantitative data and visibility of author bias. Korean Studies was the most strictly formatted of

the three, while also being the newest and shortest journal. Some of the articles contained header

formatting for each new section which helped the piece flow, and at the end of one article the

author included an appendix that included words that were specific to the authors discipline and

more detailed explanations of Korean words and phrases.1 A stylistic mechanism Korean Studies

used was taking large excerpts of primary source text and then contextualizing and analyzing the

text directly under the excerpt. The use of the quoted primary source as opposed to summary

allowed the reader to follow the specifics of the analysis as well as allowing the author to not

only present their analysis on the content of the text, but also the specific language and

construction.

The China Quarterly did an excellent job of relaying both history and theory to the reader in a

way that showed a clear connection between the contemporary theoretical framework and the

historical event that was being analyzed. Many of the articles in the journal used questions within

the article as a way to frame the argument and systematically work through the why? This

step-by-step method allowed the reader to follow the historical timeline clearly and ensured that

the author never made any leaps in timeline or logic. The China Quarterly used quantitative data,

1 Wayne Patterson, Upward Social Mobility of the Koreans in Hawaii, Korean

Studies, no. 3 (1979): 89-92.

Shewit S. Zerai

Journal Review

April 20th, 2015

such as graphs and charts, within the articles in order to support their arguments; however, the

data was used more vaguely to show magnitude of situation as opposed to representing exact

findings.2 In the discussion and analysis of data, several articles spent time exploring the

different ways this data could be and is flawed, which gave the reader a sense of flexibility in the

authors argument. The authors often used first-person pronouns and personal experience in

terms of discussing collecting data, which afforded the journal the feeling of author

accountability and transparency of bias opposed to presenting the articles as purely objective

academic work.

The Journal of Japanese Studies articles approached a lot of their subject matter through

comparison to the Western world, which can be partially attributed to many of the authors being

white, Western men. This journal is organized similarly to the previous journals in terms of the

section header format, however instead of explaining the history and then following up with

analysis, many of the authors choose to write their analysis into their telling of the history. This

has the effect of presenting the history as objective, when in fact it is incredibly biased by the

author. Upon closer reading, one can see clearly where historical fact meets the authors

interpretation of historical fact, but since both analysis and summary are often in the same

paragraph, it is harder to parse out. There is an emphasis within the pieces on defining

terminology and vocabulary, which is helpful when trying to understand the definitions within

context. Many of the articles in the journal also seem to focus on specific events or controversies

and extrapolate the history through the lens of these events as opposed to the previous journals,

which extrapolated the events from the larger historical context. The graphs and charts in the

2 Judith Banister, Mortality, Fertility and Contraceptive Use in Shanghai, The China

Quarterly, no. 70 (1977): 255.

Shewit S. Zerai

Journal Review

April 20th, 2015

journal have less disclaimers and analysis attached to them and seem to serve only their explicit

purpose, whereas the previous journal actively interrogated the circumstance of the data and how

it was collected.

The article I choose to closely analyze as a model is Ch'u Ch'iu-pai and the Chinese

Marxist Conception of Revolutionary Popular Literature and Art by Paul G. Pickowicz,

published in June 1977 in No. 70 of The China Quarterly. In this article, Pickowicz writes about

Chinese revolutionary popular literature and art through the lens of Chus criticism of the

literary elite and his celebration of the more colloquial products of art and literature in China.

Pickowiczs article serves a dual importance, firstly by examining a significant Chinese figure

whose political and social beliefs can be used as a lens to examine the increasing influence of

Western Marxist thought at the time in China, as well as Chus influence on Maos ideas and

speeches. Secondly, Pickowiczs piece brings light to the importance of popular and colloquial

art and literature and carves out a space in academia for these cultural products. Many of the

sources Pickowicz uses are from Chus direct writings and speeches, which are taken from Ting

Ching-t'ang and Wen Ts'aos Ch'i Ch'iu-pai chu-i hsi-nien mu-lu (A Chronological Bibliography

of Ch'u Ch'iu-pai's Writings and Translations) and Chus May 4th, 1932 publication of his

collected literary writings, Ch'u Ch'iu-pai wen-chi, as well as citing other Western scholars

within the field.3 In the endnotes he gives references for further readings for tangential topics a

reader might be interested in, which allows the reader the opportunity to have a more nuanced

understanding of the historical context, if they choose to. He includes disclaimers and

explanations for his own language and translation of the Chinese terminology in the endnotes,

3 Paul Pickowicz, Chu Chiu-pai and the Chinese Marxist Conception of

Revolutionary Popular Literature and Art, The China Quarterly, no. 70 (1977): 297298.

Shewit S. Zerai

Journal Review

April 20th, 2015

which gives the reader better context for the language and creates an author bias transparency

that makes it clear it is his interpretation of the text and he offers alternative translations for the

reader as well.4

Structurally, Pickowicz organizes the paper by introducing the three main players in the article,

Chu Chiu-pai, the literary elite and the colloquial art and literature of the time period, and

contextualizing them within their own history and theory. He then goes on to use Chus critique

of the literary elite as a foundation from which he builds his own argument for the significance of

colloquial art and literature in the revolutionary movement. Pickowicz utilizes rhetorical

questions in order to structure the rest of his argument by initially asking vague questions about

the revolutionary art and literature movement and developing increasingly specific questions

about the intention and impact of the literary elite on the illiterate Chinese population.5 The piece

culminates in Pickowicz describing Chus large influence on Maos writing and his rejection of

European forms and techniques, which stood in stark contrast to the styles of the revolutionary

May Fourth writers.6 Pickowicz uses a lot of comparison and dichotomy of political and social

views, such as when he discusses the elite and lower Chinese classes, as well as the urban versus

the rural, and so forth; however, in order to keep his argument from becoming too simplified into

just opposites, Pickowicz also creates divisions within the dichotomies and provides a nuanced

perspective on all of the views that he describes.

4 Pickowicz, 300.

5 Pickowicz, 298.

6 Pickowicz, 313-314.

Shewit S. Zerai

Journal Review

April 20th, 2015

Pickowicz uses somewhat colloquial language throughout the piece and does not bog down his

descriptions of history and theory with large academic terms; however, when he does indulge in

specific terminology, he always provides immediate definitions of the words or phrases. He

consistently ties back every single piece of evidence to his main point about highlighting the

importance of popular art and literature, but does so in a way that is not repetitive or

summarizing, but rather strengthens his argument as it shows the reader that it is carefully

constructed. He builds a strong foundation for his argument in Chus writing, seamlessly tying

in the primary source with his own analysis so the reader doesnt feel as though they are jumping

between two separate arguments.

Throughout all of the journals, there are common things they do well, such as formatting,

clearly showing the author bias and steeping their arguments in their primary source; however,

Pickowicz article goes farther than the rest in that he delves more deeply into his specific topic.

Whereas other articles in all the journals tackled much larger topics that required more

description than was given, Pickowicz picked a specific five-year time period, person and subject

matter which allowed him to delve deeply into all three without spreading any of the information

thin or depriving the reader of essential facts. The structure of Pickowiczs piece allows him to

give brief, but detailed, historical context without bogging down the reader with dates and events

and thus he is able to jump into the theory and critique more smoothly. By sticking with a

specific niche topic and using that as a lens to explore a larger historical event, Pickowicz was

able to give his reader a full understanding of the niche topic and the tools and base to explore

the larger historical event further.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese PastDe la EverandDiscovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese PastÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese History and Culture, volume 1: Sixth Century B.C.E. to Seventeenth CenturyDe la EverandChinese History and Culture, volume 1: Sixth Century B.C.E. to Seventeenth CenturyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- His To Rio Graphic EssayDocument3 paginiHis To Rio Graphic EssayJack JacintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is and How To Write A Historiographical EssayDocument2 paginiWhat Is and How To Write A Historiographical EssayElizabeth SwansonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russ Rev Historiog-Ryan ArticleDocument40 paginiRuss Rev Historiog-Ryan Articlemichael_babatunde100% (1)

- Notes On Literary CriticismDocument9 paginiNotes On Literary CriticismLucky AnnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical Biographical Approach 2014Document21 paginiHistorical Biographical Approach 2014Faina Rose Casimiro100% (1)

- Book Review SirajDocument3 paginiBook Review SirajFarzeen AsifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ideology and HistoryDocument21 paginiIdeology and HistorychankarunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding HistoryDocument11 paginiUnderstanding HistoryemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis of Afghan Culture in The Kite Runner by Khaled HosseiniDocument18 paginiAn Analysis of Afghan Culture in The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseinibintang alamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction Assessing Narrativism PDFDocument10 paginiIntroduction Assessing Narrativism PDFPhillipe ArthurÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Whrite HistoryDocument24 paginiHow To Whrite HistoryDouglas CamposÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annaila Syafa Azzahra - Biographical CriticismDocument2 paginiAnnaila Syafa Azzahra - Biographical CriticismannailaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Taiping Jing The Origin and Transmission of The Scripture On General WelfareDocument3 paginiThe Taiping Jing The Origin and Transmission of The Scripture On General Welfarealex_paez_28Încă nu există evaluări

- New Historicism - A Brief Write UpDocument6 paginiNew Historicism - A Brief Write UpSherrif Kakkuzhi-Maliakkal100% (2)

- Readings in Philippine HistoryDocument4 paginiReadings in Philippine HistoryDante EscuderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toward Restoration: The Growth of Political Consciousness in Tokugawa, JapanDe la EverandToward Restoration: The Growth of Political Consciousness in Tokugawa, JapanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese History and Culture, volume 2: Seventeenth Century Through Twentieth CenturyDe la EverandChinese History and Culture, volume 2: Seventeenth Century Through Twentieth CenturyÎncă nu există evaluări

- BG Writing HistoryDocument4 paginiBG Writing HistoryRakib SikderÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Uses of Literature: Life in the Socialist Chinese Literary SystemDe la EverandThe Uses of Literature: Life in the Socialist Chinese Literary SystemEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (3)

- Introduction To Literary Theories and Modern Criticism Schools of ThoughtDocument14 paginiIntroduction To Literary Theories and Modern Criticism Schools of ThoughtWindel LeoninÎncă nu există evaluări

- Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research JournalDocument7 paginiGalaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research JournalTimple KamanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical ApproachesDocument27 paginiCritical ApproachesRoman Alexander CabreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment4 FinalDocument1 paginăAssignment4 FinalBercel LakatosÎncă nu există evaluări

- History Group 2Document3 paginiHistory Group 2Sherlyn MamacÎncă nu există evaluări

- LRA 2 GuideDocument2 paginiLRA 2 GuideValeria AndradeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 书评Document3 pagini书评光木Încă nu există evaluări

- Historical Approach - Garlitos, Jochelle3ABELBDocument8 paginiHistorical Approach - Garlitos, Jochelle3ABELBRJEREEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 4 6Document10 paginiWeek 4 6Ma Clarissa AlarcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 10 Eng 16Document3 paginiModule 10 Eng 16Divine CardejonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2 - Frameworks of LiteratureDocument6 paginiModule 2 - Frameworks of LiteratureSter CustodioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing and Study Skills Services - Laurier Brantford Writing A Historiographical Essay What Is Historiography?Document2 paginiWriting and Study Skills Services - Laurier Brantford Writing A Historiographical Essay What Is Historiography?Joseyeri00Încă nu există evaluări

- Historiography - An Introductory GuideDocument251 paginiHistoriography - An Introductory GuideIoproprioio100% (2)

- Xiaoxun - wp2Document6 paginiXiaoxun - wp2api-490246818Încă nu există evaluări

- The Soviet Scholar-Bureaucrat: M. N. Pokrovskii and the Society of Marxist HistoriansDe la EverandThe Soviet Scholar-Bureaucrat: M. N. Pokrovskii and the Society of Marxist HistoriansÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Ebook PDF) How To Interpret Literature: Critical Theory For Literary and Cultural Studies 4Th EditionDocument36 pagini(Ebook PDF) How To Interpret Literature: Critical Theory For Literary and Cultural Studies 4Th Editionfrancis.lomboy214100% (25)

- Cathy N. Davidson Revolution and The Word The Rise of The Novel in America 1988Document477 paginiCathy N. Davidson Revolution and The Word The Rise of The Novel in America 1988Matt Harrington100% (1)

- Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the PresentDe la EverandEmpires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the PresentEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (46)

- Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary ChangeDe la EverandDistant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary ChangeEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (4)

- The Art of Chinese Philosophy: Eight Classical Texts and How to Read ThemDe la EverandThe Art of Chinese Philosophy: Eight Classical Texts and How to Read ThemEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Statistical Bibliography or BibliometricsDocument3 paginiStatistical Bibliography or Bibliometricsalessanpl50% (2)

- Exploring American Histories Volume 2 A Survey With Sources 3rd Edition Ebook PDFDocument48 paginiExploring American Histories Volume 2 A Survey With Sources 3rd Edition Ebook PDFmichelle.harper966100% (32)

- Chinese LiteratureDocument42 paginiChinese LiteratureAdriane0Încă nu există evaluări

- HS 211Document7 paginiHS 211Thomas SamsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Criticism - A Concise Political Hi - Joseph North PDFDocument270 paginiLiterary Criticism - A Concise Political Hi - Joseph North PDFSebastián Silva100% (1)

- Critical Approaches To Interpretation of Literature - A ReviewDocument54 paginiCritical Approaches To Interpretation of Literature - A ReviewUrdu Literature Book BankÎncă nu există evaluări

- Primary Source Paper.2022BB1 2Document9 paginiPrimary Source Paper.2022BB1 2ashish shuklaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary AnalysisDocument19 paginiLiterary Analysisrafid idkÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Shape-Shifting Body of HistoriographyDocument20 paginiThe Shape-Shifting Body of HistoriographyAlicja BembenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 5Document15 paginiModule 5Aleli Ann SecretarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mind of Empire: China's History and Modern Foreign RelationsDe la EverandThe Mind of Empire: China's History and Modern Foreign RelationsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- The Natureand Scopeof Literary ResearchDocument11 paginiThe Natureand Scopeof Literary ResearchJomar MacapagalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 07 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument79 pagini07 - Chapter 1 PDFMarkJosephÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theda Skocpol Vision and Meth Unknown PDFDocument1.336 paginiTheda Skocpol Vision and Meth Unknown PDFOlga VereliÎncă nu există evaluări

- HISTORYDocument13 paginiHISTORYJohn Carlo Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Criticism: A Concise Political HistoryDocument270 paginiLiterary Criticism: A Concise Political Historydug100% (1)

- Elizabeth S. Anker - Rita Felski - Critique and Postcritique-Duke University Press Books (2017)Document337 paginiElizabeth S. Anker - Rita Felski - Critique and Postcritique-Duke University Press Books (2017)Alexandre BrasilÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Formation of The Chinese Communist Party - Ishikawa YoshihiroDocument24 paginiThe Formation of The Chinese Communist Party - Ishikawa YoshihiroColumbia University PressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases:-: Mohori Bibee V/s Dharmodas GhoseDocument20 paginiCases:-: Mohori Bibee V/s Dharmodas GhoseNikhil KhandveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Europeanization of GreeceDocument20 paginiEuropeanization of GreecePhanes DanoukopoulosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Document15 paginiWorkweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Lenna Paguio100% (1)

- Bangalore & Karnataka Zones Teachers' Summer Vacation & Workshop Schedule 2022Document1 paginăBangalore & Karnataka Zones Teachers' Summer Vacation & Workshop Schedule 2022EshwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisDocument13 pagini4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisAnabel Marinda TulihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group Session-Week 2 - Aldi Case StudyDocument8 paginiGroup Session-Week 2 - Aldi Case StudyJay DMÎncă nu există evaluări

- India's Foreign PolicyDocument21 paginiIndia's Foreign PolicyManjari DwivediÎncă nu există evaluări

- G12 Pol Sci Syllabus FinalDocument8 paginiG12 Pol Sci Syllabus FinalChrisjohn MatchaconÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Biggest LiesDocument12 pagini10 Biggest LiesJose RenteriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harvard Case Whole Foods Market The Deutsche Bank ReportDocument13 paginiHarvard Case Whole Foods Market The Deutsche Bank ReportRoger Sebastian Rosas AlzamoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- OPEN For Business Magazine June/July 2017Document24 paginiOPEN For Business Magazine June/July 2017Eugene Area Chamber of Commerce CommunicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endole - Globe Services LTD - Comprehensive ReportDocument20 paginiEndole - Globe Services LTD - Comprehensive ReportMoamed EliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pattaya Today Volume 8 Issue 24 PDFDocument52 paginiPattaya Today Volume 8 Issue 24 PDFpetereadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial and Management Accounting Sample Exam Questions: MBA ProgrammeDocument16 paginiFinancial and Management Accounting Sample Exam Questions: MBA ProgrammeFidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- EBO 2 - Worldwide Energy Scenario - FINALDocument15 paginiEBO 2 - Worldwide Energy Scenario - FINALmodesto66Încă nu există evaluări

- Sample Motion To Strike For Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) in CaliforniaDocument5 paginiSample Motion To Strike For Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) in CaliforniaStan Burman91% (11)

- Mahabharata of KrishnaDocument4 paginiMahabharata of KrishnanoonskieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pietro Mascagni and His Operas (Review)Document7 paginiPietro Mascagni and His Operas (Review)Sonia DragosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sport in The Eastern Sudan - 1912Document308 paginiSport in The Eastern Sudan - 1912nevada desert ratÎncă nu există evaluări

- MSME - Pratham Heat TreatmentDocument2 paginiMSME - Pratham Heat TreatmentprathamheattreatmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cost-Effective Sustainable Design & ConstructionDocument6 paginiCost-Effective Sustainable Design & ConstructionKeith Parker100% (2)

- Deped Format of A Project Proposal For Innovation in SchoolsDocument6 paginiDeped Format of A Project Proposal For Innovation in SchoolsDan Joven BriñasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Why The Working Class?: Education For SocialistsDocument32 pagini1 Why The Working Class?: Education For SocialistsDrew PoveyÎncă nu există evaluări

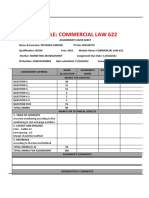

- Claw 622 2022Document24 paginiClaw 622 2022Priyanka GirdariÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRPC MergedDocument121 paginiCRPC MergedNishal KiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pointers For FinalsDocument28 paginiPointers For FinalsReyan RohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bilal Islamic Secondary School-Bwaise.: Rules Governing PrepsDocument2 paginiBilal Islamic Secondary School-Bwaise.: Rules Governing Prepskakembo hakimÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV - Mai Trieu QuangDocument10 paginiCV - Mai Trieu QuangMai Triệu QuangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educ 60 ReviewerDocument6 paginiEduc 60 ReviewerJean GuyuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dayalbagh Educational Institute: Application Number Application FeesDocument2 paginiDayalbagh Educational Institute: Application Number Application FeesLuckyÎncă nu există evaluări