Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Kysilka Understanding Integrated Curriculum (Recovered)

Încărcat de

Eka PrastiyantoDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Kysilka Understanding Integrated Curriculum (Recovered)

Încărcat de

Eka PrastiyantoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Vol. 9 No.

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Understanding integrated

curriculum

MARCELLA L. KYSILKA

University of Central Florida

ABSTRACT

Integrated curriculum is currently being advocated in the United States to 'solve'

many of the curriculum problems confronting education. Models of curriculum integration permeate the professional literature, yet there is little consensus as to exactly

what is meant by integrated curriculum and how to establish such curricula in the

publicly funded schools. The language of curriculum integration is confusing and

leads to uncertainty and concern about the potential of integrated curriculum to

impact positively on schools. Placing the models on a curriculum continuum will

reveal that they range from traditional discipline-based, objective-driven, teachercontrolled models to interest-based, student exploration. Although historically

research supports integrative curriculum, there is a paucity of current research which

would support arguments for restructuring the American curriculum in this fashion.

Additionally, there is a great deal of resistance to change both from within and outside

the educational community to massive curriculum restructuring.

KEYWORDS

curriculum; integrated curriculum; curriculum restructuring; interdisciplinary;

multidisciplinary; core curriculum.

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

As with many 'new' ideas in education, integrated curriculum has permeated

the professional literature with numerous articles advocating its adoption by

schools to 'solve' many of the curriculum problems confronting education.

Commercial publishers have quickly designed and promoted materials which

'integrate' the curriculum. A quick look at any professional organization's

The Curriculum Journal Vol 9 No 2 Summer 1998

British Curriculum Foundation 1998

197-209

ISSN 0958-5176

198

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

programme of events for their national and international meetings will reveal

an increasing number of presentations focusing on 'integrated' curriculum.

The attention to integration is growing exponentially and with such rapid

growth comes confusion, uncertainty and concern over exactly what is meant

by integration and how schools ought to go about implementing such ideas.

At the moment it seems that integration means whatever someone decides

it means, as long as there is a 'connection' between previously separated

content areas and/or skill areas. Before anv teachers or administrators can

successfully plan for integrated curriculum: a much clearer concept of what

is meant by integration needs to be understood. Most advocates of integrated

curriculum will base their arguments on some fundamental beliefs. Supported

by positions taken by Dewey (1916), Kilpatrick (1918), Oberholtzer (1937),

Squires (1972), Vars (1969, 1987), and Beane (1993 ), advocates indicate that

an integrated curriculum is precipitated by the following:

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Genuine learning takes place as students are engaged in meaningful, purposeful activity.

The most significant activities are those which are most directly related to

the students' interests and needs.

Knowledge in the real world is not applied in bits and pieces but in an integrative fashion.

Individuals need to know how to learn and how to think and should not

be receptacles for facts.

Subject matter is a means, not a goal.

Teachers and students need to work co-operatively in the educative process

to ensure successful learning.

Knowledge is growing exponentially and changing rapidly, it is no longer

static and conquerable.

Technology is changing access to information, defying lock-step, sequential, predetermined steps in the learning process.

These beliefs are obviously not new, nor are they necessarily confined to an

integrated approach to curriculum, nor must they be packaged as a whole.

However, if one examines them and believes that all of them are valid curriculum beliefs, then a means by which they can all be employed is through

curriculum integration.

In attempts to help teachers understand curriculum integration, various

authors have presented their models of 'integrated curriculum'. These models

were designed to explain the various stages of curriculum integration and to

'ease the concern' many educators have about how to 'blend' content and/or

create 'seamless' curricula.

Robin Fogarty, in her book, The Mindful School: How to Integrate the Curriculum (199la) has identified ten models of curriculum integration, ranging

from the fragmented disciplines (traditional) approach to a completely

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

networked approach to curriculum planning. Between the fragmented and

networked points of Fogarty's continuum, she identifies eight other models

of curriculum integration:

Connected: ideas within each content area are related to each other and

connections are made between prior knowledge and knowledge yet to be

learned.

2 Nested: the emphasis is on learning skills and organizational skills needed

within each discipline in order completely to understand the content of the

discipline. For example, in a mathematics lesson in third grade, a thinking

skill such as classifying is related to specific knowledge of geometric

shapes, tied together with charting or some other 'organizing' skill so that

students understand the characteristics of geometric shapes, enhance their

classification skills and develop organizational skills by which information

can be stored and used for further reference. In this model, the content area

still remains as the major focus of the lesson, but the skills of thinking and

organizing ideas are highlighted within the lessons.

3 Sequenced: topics within a discipline are rearranged to coincide with those

of another discipline. For example, a tenth grade mathematics teacher

might teach a unit on probability at the same time as the biology teacher

teaches a unit on genetics. The application of probability to genetics thus

becomes apparent to the students and helps them to better understand both

probability as a mathematical concept and the application of probability to

the understanding of genetics.

4 Shared: disciplines are 'partnered' and units planned to focus on 'over-

lapping ideas or concepts', e.g. English and history are 'partnered' for a unit

on the Civil War. The English teacher selects specific American literature

relating to the Civil War which deals with patriotism, family, duty, loyalty,

commitment and honour, while at the same time the students are learning

about the battles, decisions and events which occurred during the war.

Thus students might gain a better understanding of what war meant to the

people as well as what the war meant to the stability and survival of the

country.

5 Webbed: themes form the base of the curriculum. Disciplines use the

themes to teach specific concepts, topics and ideas within the disciplines.

For example, the teachers may select ethics as a theme. Each teacher, then,

within his/her own discipline will address ethics as it is appropriate to the

subject matter. This could mean discussing plagiarism in English class as

the students prepare a research paper, analysing decisions made by politicians in a political science class, establishing rules of proper sportsmanlike behaviour in physical education classes, perhaps concentrating on

199

200

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

censorship of artistic work in fine arts classes, debating issues of genetic

engineering in science, and looking at the proper use of computer technology in a mathematics class. The disciplines remain intact, the content of

the disciplines is not changed, but the teachers make a special effort to

address the theme as they individually work with the students on the

content to be learned.

6 Threaded: a 'meta-curriculum' is designed around specific thinking, social

or study skills and the content becomes the vehicle for these skills to be

learned. At the same time, the classroom teacher infuses ideas about how

one learns (multiple intelligences) and aids to learning (technology) which

can help the students develop their metacognitive skills, i.e. they learn more

about how they learn. For example, in an elementary school, a grade level

team decides to focus their activities for two weeks on helping students to

learn how to draw inferences from available data. So in language arts, as they

are reading their stories, the teacher asks them to predict possible endings

to the stories, while in mathematics she might ask them to estimate an

answer to a problem, and in science establish a hypothesis for an experiment.

In social studies, the students might be asked to generalize from one set of

events to another. In all these cases, the teacher emphasizes that the students

are making reasonable decisions based upon sets of given data and they

would be encouraged to examine the 'credibility' of their inferences. Again,

the content is preserved while the emphasis is on the process of learning.

7 Integrated: teams of teachers work together in all disciplines to find over-

lapping concepts and ideas around which they can plan units of study and

implement them in common teaching time. This model is perhaps one that

is currently used in many middle school programmes whereby interdisciplinary teaching teams work together to build units in which they share

teaching responsibilities. Here, discipline lines begin to fade. Other

examples of an integrated model as defined by Fogarty would be whole

language in the elementary school and the humanities as taught in many

high schools, colleges and universities.

8 Immersed: a student becomes immersed in a field of study and filters information from content areas through his/her own lens. Integration becomes

the responsibility of the student. This 'model' of curriculum integration is

what is perceived to be the model of learning advocated by many doctoral

programmes. The learner is in control of the knowledge learned, the strategies used and the sharing of that knowledge with other students, the

faculty and the academic world.

At the end of her continuum is her concept of networked integration. Networked integration requires learners to reorganize relationships of ideas

within and between the separate disciplines as well as ideas and learning

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

strategies within and between Learners. At this level of integration, the learners should be pro-active in the learning process and initiate their own searches

for information, skills and concepts, relying on experts and other learners as

resources for their own learning. A good example of this would be a social

researcher scanning the electronic information highway to find and sort

through information which might be pertinent to the research in which

he/she is engaged. All sources are initially valid and the researcher determines

what information he/she wishes to pursue and the extent to which that information will be used in his/her research. This is a highly sophisticated level of

curriculum integration and one which might not become an integral part of

a K-12 curriculum. The degree to which it can be used is really dependent

upon the individual learner and his/her teacher.

The models presented by Fogarty raise the issue of what is meant by curriculum integration. If curriculum integration means the incorporation of

processing skills and metacognitive skills within the disciplines-based curriculum, then her models accommodate that concept. If curriculum integration means the dismantling of disciplines as we now know them for a more

comprehensive notion of curriculum, then only her integrated, immersed and

networked models are helpful in our rethinking of the curriculum.

One of the issues made evident through an examination of Fogarty's work

is the relationship between what we plan to teach and how we plan to teach

it. Although most of us would agree that the what and how of curriculum are

inextricably intertwined, we must also recognize that too often the 'how to'

takes precedent over the 'what'. Thus the what can get 'lost' in the decisionmaking process which often leads to superficiality of content. For example,

if our concerns for integrating thinking skills processes into the curriculum

take precedence over the subject matter the students are going to think about,

we may have students learning thinking skills and practising those skills on

irrelevant and unimportant content. The same may be said of 'partnershipping' of subject matter teachers. If teachers are working together to help

students make meaning out of the separate disciplines, then it behoves the

teachers to develop lessons which are both meaningful within the disciplines

as well as across the disciplines. Such planning takes a tremendous amount of

time and thought on the part of teachers.

Heidi Hayes Jacobs (1989) has also attempted to define curriculum options

for an integrated curriculum. She has established five options from disciplined-based to complete programme integration. Between the two ends of

her curriculum options are 'degrees' of integration.

Parallel disciplines: the disciplines maintain themselves as separate entities;

however, teachers attempt to sequence topics so that related ideas are

taught concurrently within the separate disciplines. (This is similar to

Fogarty's sequenced model.)

201

202

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

2 Multidisciplinary: related disciplines are brought together in a formal way

for analysis and study, e.g. humanities, fine arts, political history. This type

of integration supports the creation of a 'new' course to be offered by

finding relationships between existing disciplines.

3 Interdisciplinary: specific units or courses of study are constructed to bring

together all the disciplines within the school's curriculum. Units of study

are designed around themes, ideas or issues which emerge from the regular

curriculum. The units are taught for a specified period of time (two weeks,

a month, a semester) determined by the teachers. Specific blocks of time

are set aside in the daily or weekly schedule to accommodate the interdisciplinary units. However, the units do not supplant the existing disciplines, they are complementary to them.

4 Integrated day: a theme-based full-day programme focusing on student

interests and needs. Based upon the British Infant School movement of the

1960s, this model is frequently promoted as a viable alternative to curriculum structure in early childhood programmes.

5 Complete integration: students determine their curriculum out of their life

experiences, needs and interests. An example of this would be a school such

as Summerhill where students decide what they want or need to learn based

upon their interests. The programme at New College in Sarasota, Florida,

allows each student's curriculum to consist of 'courses' and activities

deemed most appropriate for the goals established by the students. At New

College there is not one established curriculum which all students must

take in order to complete their degrees. Specific activities, e.g. a wilderness

survival experience or a congressional internship, are built into their programmes to provide them with experiences important to their development

as a person, learner and scholar. Independent study and learning contracts

are very much a part of the curriculum. Students who function best in this

environment are self-motivated, independent, goal-oriented learners.

Jacobs has concentrated her definitions of integration on what happens

specifically with respect to the disciplines. Do the disciplines remain as separate entities, taught in regular time-frames, or are their boundaries broached

and new time-frames created to better explore learning possibilities? Her

options are focused on the organizational structure of the curriculum and are

less concerned with how the curriculum is taught, whereas many of Fogarty's

models were more focused on the how rather than the organizational structure of the curriculum.

Susan Drake (1993) uses the terms multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and

transdisciplinary to describe frameworks for planning integrated curriculum. In her schema, multidisciplinary means that the same topic or theme is

addressed by each of the separate disciplines, thus retaining the integrity of

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

each discipline. Interdisciplinary, on the other hand, is defined as identifying specific skills, processes or ideas which are common to all disciplines and

addressing those through the disciplines. Most of Drake's suggestions focus

on learning how to learn as the organizing factor for this approach to curriculum planning. Her final framework is transdisciplinary. Here the focus

of curriculum planning is a 'life-centered approach' (41). Knowledge is

examined as it exists in the real world. The content to be learned is determined by the theme and the expressed interests and needs of the students,

rather than predetermined by some curriculum framework or set of curriculum objectives.

In addition to the definitions presented by Fogarty, Jacobs and Drake,

other terminology is used to describe curriculum integration. Correlation,

fusion and core are used by Vars (1987), while Stevenson and Carr (1993)

prefer to use the term integrated studies, and Maurer (1994) defines interdisciplinary curriculum as co-related (re-sequencing content from different

disciplines to 'match'), multidisciplinary (creation of a new course which

blends content from different disciplines), interdisciplinary ( organizing

content around broad themes) and integrated day (an extensive restructuring

of the curriculum). Still another term has been used, cross-disciplinary,

usually in conjunction with teaching reading, writing and thinking skills

across the disciplines. So what does all this 'new language' mean? In the arena

of integration, how can we make sense out of all this terminology?

The 'new language' of curriculum is descriptive of ways to plan and organize the curriculum in order to bring meaning to the curriculum - a means of

making the curriculum more connected to what is happening in the real

world. For the curriculum to become more meaningful to learners, they need

to see a connection between what they are learning in school and what information, skills and knowledge they use in real life situations. Since in real life

content is not segregated into its respective pieces, 'integrationists' contend

that the way in which students should learn content in school is not in segregated, unrelated bits and pieces, but as a whole body of related information

which is then utilized appropriately in daily life activities. Thus integrationists are examining ways to bring meaning to the curriculum by rethinking how the curriculum can be planned, organized or restructured to provide

these opportunities for meaningful learning.

THE CURRICULUM CONTINUUM

An examination of the current use of the 'new language' of curriculum reveals

a continuum of thinking about the curriculum. Movement up or down the

continuum is dependent upon what role the disciplines (subject matter) play

in the organization of the curriculum, what role 'processes' play in thinking

203

204

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

about the curriculum, and what role the teachers and learners play in developing and carrying out the curriculum.

At one end of the continuum is the discipline or subject-centred approach

to learning, the current 'traditional' model. Here content is taught in its separate state and any integration that takes place is often haphazard and resides

solely within the learner. No purposeful attempt on the part of the teacher is

made to connect what is learned in one class to what is learned in another or

to what is needed outside the classroom. If students raise issues or concerns

about the relationship of what they are learning in their history class to what

they saw on television or what they read in their literature class, the teacher

may address the issue or concern, but the teacher is not perceived to be

responsible for seeking out opportunities to develop relationships for the

students.

The next stage on the continuum still views the disciplines as the major

focus of the curriculum; however, deliberate efforts are made on the part of

the teachers to connect the learning to real life situations and/or other curricular areas. Common skill areas between the subjects may be identified and

reinforced by having the teachers in the various content areas teach the same

skills at the same time within their specific curriculum. Natural connections

between content areas are sought and teachers rely on one another to make

the natural connections obvious to their students. At this stage, the subject

matter remains intact and at the centre of the classroom learning. Time

periods for content instruction are still adhered to. Curriculum frameworks

describing specific skills and information to be learned at designated grade

levels and within content areas are followed. What might change is the

sequence of content in order to make connections, or some time set aside for

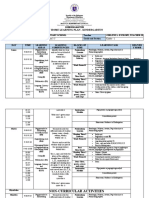

'---v---"

I+

Multifaceted lens

Sequenced

Broad themes

Correlated ideas

Process themes

Focused content

Student interests

themes

New courses

Multiple lenses

Modified courses

Content

Separate

subjects

Time

Distinct

Distinct

units/periods

units/periods

Teachers

Separate

Students

Receivers

Total integration

Interdisciplinary

Disciplined-based

Separate

disciplines

s;

v'

Student needs/interests

Cross disciplines

Integrated day

Apprenticeships

Experiences

Blocked

Varied

Separate

Paired/teamed

Teamed/facilitators

Receivers/doers

Doers/decisionmakers

Creators

Decision-makers

Creators

Independent

investigators

Figure 1 Integrated curriculum continuum

.J

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

'practical applications' of content through activities, use of guest speakers,

etc. Importantly, at this stage of the continuum, the teacher assumes responsibility for developing meaningful experiences and connections for the

students. There is a deliberate effort to find relationships between the various

content areas and between the content areas and real life situations which

enhance the learning of the students.

The next stage of the continuum requires a breaking down of the rigid

content area boundaries. The focus at this stage is not the disciplines per se,

but rather the set of skills, concepts, themes, ideas and applications of content

that is deemed important to be learned. From these identified areas the curriculum is structured, so 'traditional' content may be altered or even abandoned in favour of more appropriate curriculum content. Efforts are made to

blend content both within and between disciplines to enhance the understanding of a particular theme, organizing concept or skill. For example,

suppose an organizing theme for a tenth grade unit becomes 'celebrating cultural diversity'. The teachers decide that they want to specifically address the

time period from 1700-1900. The science, mathematics and social studies

teachers might develop lessons related to the contributions of various cultures to the science knowledge base and the concomitant persecution of

scientists as their ideas challenged the religious beliefs and political structures

of the times. The language arts teachers might co-ordinate their efforts with

the art and music teachers to examine how literature, art and music from the

various cultures reflected the thoughts of peoples of the time and became a

means of documenting the social/political atmosphere of communities. Even

the physical education teachers could examine the important role of 'sports'

in the development of mind, body and spirit. Thus the traditional content of

biology, algebra or geometry, world history and literature, art or music

appreciation and physical education becomes less obvious and is replaced by

a much broader, richer and connected set of lessons which try to emphasize

how all these areas were affected by and contributed to the diversity of people

who lived within the existing world of the time.

The integrated lessons designed by the teachers could occur within existing time slots of the curriculum. However, in order for students to see how

the teachers make connections between content areas, provision must be

made for teachers to share common teaching time. Double periods, a half day

once a week or other block-time structures can be created to provide the

teachers with common teaching time. When students see how their teachers

transverse the 'artificial', but to the students 'real', lines of content thev

,

might find it easier to model their behaviour on that of their teachers.'

At the furthest end of the continuum is that of an integrated curriculum.

Ar this stage, all specificity to disciplines disappears. Topics of study are

chosen by the students in conjunction with the teachers because the topics

are deemed important in the development of the intellectual, psychological,

205

206

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

emotional and/or social abilities of the students. Once a topic or theme is

identified, teachers and students establish the activities, strategies and knowledge needed to help students examine the topic or theme. Teachers provide

opportunities for students to explore on their own. Little attention is given

to specific curriculum frameworks or established content objectives. Rather,

the assumption is made that students will learn what is essential as thev

pursue the topic or theme under study. The important decision in this

approach to curriculum organization is the establishment of the themes and

topics around which the curriculum is organized. If the themes and topics are

appropriately established by the teachers and their students, then opportunities will exist to explore appropriate disciplines. No content will be

neglected; it will be used as needed within the curriculum. Time might be set

aside during the unit to study specific content needed to continue the investigation started by the students. In this approach, all content areas play an

important role in the curriculum. Students and teachers have the opportunity

to explore subject matter as well as choose appropriate strategies to use for

the exploration and the sharing of the information with their colleagues. At

this stage, much more responsibility is placed on the students to find and synthesize relationships between content areas, and teachers assume the role of

facilitators in the learning process.

The continuum for curricular organization, then, moves the selection of

what and how something is taught from predetermined objectives and

content-specific textbooks, to teacher-generated connections between the

different disciplines, to processing and theme-based ideas for curriculum

organization, to teachers and students co-operatively determining what they

should learn and how they should learn it to best meet the needs and interests of students. The control of the curriculum moves from textbook publishers and subject matter 'experts' to teacher-facilitated student choice.

As the curriculum continuum is examined, it must be noted that there is

no one best organizational structure for curriculum integration. The success

of any curriculum lies within the teachers' acceptance of that particular curriculum. Some teachers are not going to be comfortable working in a truly

integrated curriculum, with no apparent structure, no predetermined goals to

achieve and no specific content to be mastered. Other teachers may find this

approach challenging and exciting, providing them with the opportunity and

freedom to create and explore a variety of learning adventures with their

students. Some teachers might want to venture into curriculum reorganization cautiously, perhaps trying to co-ordinate a lesson with another teacher

to see how making connections might work best for them. Some teachers may

never want to move away from the 'safety' of their disciplinary approach to

learning and would, perhaps, not be effective in delivering any other type of

curriculum.

The continuum should not be viewed as a means of forcing teachers to

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

reorganize their curriculum but, more importantly, as a vehicle to help them

rethink what they are currently doing and provide some guidance in determining how they might do things differently. Hopefully, teachers and

administrators can find a stage on the continuum with which they can become

comfortable as a team and produce a curriculum which becomes more

meaningful to and connected with the real life experiences of their students.

The integrated curriculum movement in the United States is currently

more rhetoric than activity. There are examples of teachers working together

on units of instruction and some schools making efforts at 'integrating' the

curriculum; however, the impact of these ideas on what is actually happening in schools is limited. Reasons for the reluctance of teachers and schools

to become more aggressive in changing the way the curriculum is constructed

and delivered to the students have a great deal to do with the assessment

activities within the states. As long as students are expected to demonstrate

specific levels of achievement on standardized tests which measure factual

information, teachers - who are held responsible for student performance are wary of engaging in curriculum restructuring. What if, in attempts at

helping students make meaning out of the curriculum through a more integrated approach to learning, students 'fail to achieve' on the standardized

tests? The 'test-driven' mentality of legislatures throughout the United States

who pass laws requiring testing at specified grade levels and in specific subject

areas hampers the development of more integrated curriculum efforts. If

students 'fail to achieve', the teachers are held accountable. In some states,

students' failure to achieve on statewide assessment tests can mean the dismissal of teachers. Working in such an environment, teachers are hesitant to

try ideas which may or may not improve students' achievement on required

assessment tests, even if ultimately the students' ability to apply their knowledge to real world activities improves.

Another reason teachers are reluctant to engage in curriculum restructuring is that of time. In order for teachers to plan properly and develop integrated curriculum at whatever level they feel comfortable with, they must

have adequate planning time. They need time to develop themes and ideas,

they need time to gather necessary information to plan, they need time to

work collaboratively. Most teachers do not have the time and most administrators will not provide the time for the teachers to work together. Unless an

entire school staff is committed to changing the curriculum, and deliberately

works to ensure that the change will occur, there is little hope that curriculum integration will become the 'norm' in the public schools. Individual

teachers are very limited in what they can accomplish. They can help students

to see relationships, they can find ways to apply information to real world

activities, but the overall impact they may have on helping students see the

connections between what they learn in school and what thev need to survive

,

in society is slight.

207

208

THE CURRICULUM JOURNAL

Vol. 9 No. 2

Parents also influence what may or may not happen in the public schools.

Parents are very resistant to change. They want their children to achieve and most parents' notions of achievement are to duplicate what they did

when they were at school. Unfortunately, times have changed, students have

changed, the quantity of knowledge has changed. What has adequately served

us in the past in our schools is simply not working today for the majority of

our students. Yet talk of changing the curriculum better to meet the needs of

today's society is met with scepticism from the parents, or at least from those

parents who care enough to be actively engaged in school issues.

A final reason which prevents major curriculum reform from being inclusive of curriculum integration is the knowledge base of the teachers. In the

United States secondary teachers are educated in very narrow disciplines,

while elementary teachers have little specific discipline training. Thus

teachers who are expected to work together to provide an integrated

approach to learning may find their own lack of information the greatest

impediment of all. If, as a mathematics teacher, I have no knowledge of how

mathematics is used in other areas, or as a history major I have never explored

literature, or art, or music, I may find it difficult to share my 'ignorance' with

my fellow teachers. Likewise, as an elementary teacher, if I have but a superficial knowledge of subject matter content, I may find it difficult to build sensible theme-based curriculum units. If teachers are going to be expected to

'blend' content areas, then they need to be more broadly and deeply educated. They also need to be taught by professors who can demonstrate the

interconnectedness of content and the students should be expected to demonstrate their abilities to see relationships between ideas and events. The entire

teacher education process needs to be restructured if we are to have teachers

who can operate within a different model of the school curriculum.

The theory of curriculum integration has great potential for making a

difference in schools. Historically we have evidence that curriculum integration works (Kilpatrick, 1918; Collings, 1923; Oberholtzer, 1937; Cremin,

1961; Squires, 1972). However, the environment in which publicly funded

schools are operating today is very different from the environment that

existed when the early studies on curriculum integration were completed.The

reality of making curriculum integration happen in schools today is another

story. The resistance is strong: it comes from parents, teachers, students,

administrators and legislators. The current advocates of curriculum integration have written much about how to do it and they have developed

various models with which to begin, but they do not have enough hard data

collected on the implementation and success of integrated curriculum projects to offset the concerns. The research base which might influence

decision-makers simply does not exist.

Is curriculum integration just another fad? ls it no more than rhetoric? Is

ir another grasp at finding something that will revitalize education and make

UNDERSTANDING INTEGRATED CURRICULUM

it 'work'? Perhaps. Jerome Bruner (1997) has indicated that the purpose of

education is the making of meaning, and that can only occur if the culture of

education is so designed to make that happen. Culture is an attitude, not a

curriculum design. Maybe we need to worry more about attitude. With the

right attitude, the curriculum design may be irrelevant.

REFERENCES

Beane, J. (1993) 'Problems and possibilities for an integrative curriculum'. Middle

School journal 1: 18-23.

Bruner, J. (1997) The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Collings, E. ( 1923) An Experiment with a Project Curriculum. New York: Macmillan.

Cremin, L. (1961) The Transformation of the Schools. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Dewey, J. (1916) Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan.

Drake, S. (1993) Planning Integrated Curriculum: The Call to Adventure. Alexandria,

VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Fogarty, R. (1991a) The Mindful School: How to Integrate the Curriculum. Pallantine, IL: Skylight Publishing.

Fogarty, R. (1991 b) 'Ten ways to integrate curriculum'. Educational Leadership 47(2):

61-5.

Jacobs, H. (ed.) (1989) Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and Implementation.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kilpatrick, W (1918) 'The project method'. Teachers College Record 19(1): 318-34.

Maurer, R. (1994) Designing Interdisciplinary Curriculum in Middle, junior High,

and High Schools. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Neill, A. S. (1982) Summerhill. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Oberholtzer, E. (1937) An Integrated Curriculum in Practice. Bulletin No. 364. New

York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Squires, J. (ed.) (1972) A New Look at Progressive Education. Washington. DC:

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Stevenson, C. and Carr, J. (eds) (1993) Integrated Studies in the Middle School:

Dancing Through \Valls. New York: Teachers College Press.

Vars, G. (ed.) (1969) Common Learnings: Core and Interdisciplinary Team

Approaches. Scranton, PA: Intext.

Vars, G. (1987) Interdisciplinary Teaching in the Middle Grades. Columbus, OH:

National Middle School Association.

209

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Connected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeDe la EverandConnected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeTricia A. FerrettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Curriculum - Jacobs 2003Document103 paginiIntegrating Curriculum - Jacobs 2003Rolando Flores Amaralis CaroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Studies As Integrated CurriculumDocument4 paginiSocial Studies As Integrated CurriculumMaria Angelica Mae BalmedinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 CLIL As A Theoretical ConceptDocument6 pagini3 CLIL As A Theoretical ConceptCarolina garcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interdisciplinary CurriculumDocument18 paginiInterdisciplinary CurriculumAndi Ulfa Tenri Pada100% (1)

- Lesson 2Document6 paginiLesson 2Zeineana OxfordÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selection and Organization of Curriculum ContentDocument4 paginiSelection and Organization of Curriculum ContentJulie Rose CastanedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trabajo CurriculumDocument6 paginiTrabajo CurriculumPamela Rodriguez RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Models of CR IntegrationDocument9 paginiModels of CR IntegrationAdrian0Încă nu există evaluări

- Cus 3701 Ass 2Document8 paginiCus 3701 Ass 2Henko HeslingaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History For AllDocument9 paginiHistory For AllBen RogaczewskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tyler & Wheeler Curriculum ModelDocument8 paginiTyler & Wheeler Curriculum Modelliliyayanono100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines Commission On Higher Education Region VDocument9 paginiRepublic of The Philippines Commission On Higher Education Region VshielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2 Lesson 2Document8 paginiModule 2 Lesson 2Mary Joy PaldezÎncă nu există evaluări

- CurruculumDocument11 paginiCurruculumbernadette embienÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research On Curriculum DevelopmentDocument16 paginiResearch On Curriculum Developmentmariejo100% (8)

- Untitled DocumentDocument9 paginiUntitled DocumentIsidora TamayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Trends in EducationDocument65 paginiCurrent Trends in EducationAlish ReviÎncă nu există evaluări

- LECTURE 4 Blended Teaching NotesDocument10 paginiLECTURE 4 Blended Teaching Notesmuhiastephen005Încă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum NotesDocument21 paginiCurriculum Notescacious mwewaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selection and Organization of Curriculum PDFDocument4 paginiSelection and Organization of Curriculum PDFDawn Bungalso GallegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Models of Curriculum IntegrationDocument9 paginiModels of Curriculum IntegrationMahmoud DibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samar Colleges Inc. Catbalogan City, Samar: School Curriculum ApproachesDocument8 paginiSamar Colleges Inc. Catbalogan City, Samar: School Curriculum ApproachesLemuel AyingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 2 Report GodfreyDocument56 paginiGroup 2 Report GodfreyTabor, Trisia C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Module 4Document14 paginiModule 4ROSE ANN MAULANAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 4 John Renier AlmodienDocument15 paginiModule 4 John Renier AlmodienEfigenia Macadaan Fontillas75% (4)

- Midterm - Act 1.Document5 paginiMidterm - Act 1.Lynnah SibongaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prelim Activity - 001-ReyArroyoDocument8 paginiPrelim Activity - 001-ReyArroyoNon SyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stenhouse 1968 Humanities Curriculum Project JournalDocument5 paginiStenhouse 1968 Humanities Curriculum Project JournalAntero GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secondary School Curriculum and InstructionDocument80 paginiSecondary School Curriculum and Instructionguta lamessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Act Mod 4Document5 paginiAct Mod 4MARK VIDALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thematic Teaching in Social StudiesDocument5 paginiThematic Teaching in Social Studieszanderhero30Încă nu există evaluări

- Designing An Integrated Curriculum For Preschool: Greg Tabios Pawilen, Jaeson P. Arre, Eloida F. LindoDocument20 paginiDesigning An Integrated Curriculum For Preschool: Greg Tabios Pawilen, Jaeson P. Arre, Eloida F. Lindohoomesh waranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of Thematic CurriculaDocument18 paginiTheory of Thematic CurriculaDwight AckermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- MODULE II Crafting The CurriculumDocument6 paginiMODULE II Crafting The CurriculumJamillah Ar GaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ued 496 Isabella Szczur Student Teaching Rationale and Reflection Paper 3Document7 paginiUed 496 Isabella Szczur Student Teaching Rationale and Reflection Paper 3api-445773759Încă nu există evaluări

- 97 Toward A Theory of Thematic CurriculaDocument25 pagini97 Toward A Theory of Thematic CurriculacekicelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maevelle Joy Ug-WPS OfficeDocument4 paginiMaevelle Joy Ug-WPS Officejohnmauro alapagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2 EuDocument37 paginiModule 2 EuRhea Tamayo CasuncadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Out - Joh ICTDocument15 paginiOut - Joh ICTAshrafÎncă nu există evaluări

- CGS03025026 Take Home Examination CDDocument11 paginiCGS03025026 Take Home Examination CDAzizol YusofÎncă nu există evaluări

- BENLAC Module 4 Integrating New Literacies in The CurriculumDocument8 paginiBENLAC Module 4 Integrating New Literacies in The CurriculumJustine Vistavilla PagodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum TheoryDocument20 paginiCurriculum Theoryrandy_hendricks100% (1)

- Report - Curriculum Design and OrganizationDocument43 paginiReport - Curriculum Design and OrganizationJanet Bela - Lapiz100% (6)

- Integrated Interdisciplinary CurriculumDocument15 paginiIntegrated Interdisciplinary Curriculumapi-357354808Încă nu există evaluări

- Inclusive Education Literature ReviewDocument6 paginiInclusive Education Literature Reviewafmzrxbdfadmdq100% (1)

- Ten General Axioms of Curriculum DevelopmentDocument4 paginiTen General Axioms of Curriculum Developmentrichel maeÎncă nu există evaluări

- FS IntegrationDocument30 paginiFS IntegrationJoesery Padasas Tuma-obÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10.4324 9780367198459-REPRW180-1 WebpdfDocument7 pagini10.4324 9780367198459-REPRW180-1 WebpdfRefinÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Every Teacher Should Know: Reflections On "Educating The Developing Mind"Document6 paginiWhat Every Teacher Should Know: Reflections On "Educating The Developing Mind"Fitra Mencari SurgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Designs and Oliva's 10 AxiomsDocument8 paginiCurriculum Designs and Oliva's 10 AxiomsLiza SalvaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ma'am LoveDocument13 paginiMa'am LoveRoj MoranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2003 Curriculum IntegrationDocument15 pagini2003 Curriculum IntegrationMary Grace Peralta ParagasÎncă nu există evaluări

- U1 3-GeneralSubjectDidactics (GDiazMaggioli)Document4 paginiU1 3-GeneralSubjectDidactics (GDiazMaggioli)AdrianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jacobs - Interdisciplinary CurriculumDocument9 paginiJacobs - Interdisciplinary CurriculumAdrian0Încă nu există evaluări

- Models For Teaching ThinkingDocument5 paginiModels For Teaching Thinkingbelford11Încă nu există evaluări

- The Science Curriculum Framework: An Enrichment Activity: #What'Sexpectedofyou?Document6 paginiThe Science Curriculum Framework: An Enrichment Activity: #What'Sexpectedofyou?Justine Jerk BadanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project - (U) - 3 - Bewket Aschale (Effective Pedagogy in Sc. or Math)Document7 paginiProject - (U) - 3 - Bewket Aschale (Effective Pedagogy in Sc. or Math)bewket.aschaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 4 Integrating New Literacies in The CurriculumDocument12 paginiModule 4 Integrating New Literacies in The CurriculumJaymark RebosquilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- DataDocument2 paginiDataEka PrastiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Didactic Reduction: Literature Art Ancient Greek EducationDocument3 paginiDidactic Reduction: Literature Art Ancient Greek EducationEka PrastiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soil Exam QuestionsDocument13 paginiSoil Exam QuestionsEka Prastiyanto100% (1)

- Process Skills DefinedDocument3 paginiProcess Skills DefinedEka PrastiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Newly Designed Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis Device To Fabricate YBCO TapesDocument4 paginiA Newly Designed Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis Device To Fabricate YBCO TapesEka PrastiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Diffusion, Activation and Microstructure Evolution of Phosphorus Implanted Into PolysiliconDocument1 paginăThe Diffusion, Activation and Microstructure Evolution of Phosphorus Implanted Into PolysiliconEka PrastiyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter To Clawson SchoolsDocument1 paginăLetter To Clawson SchoolsWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barefoot Leadership - Alvin Ung PDFDocument2 paginiBarefoot Leadership - Alvin Ung PDFTan ByongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Description of Class Teaching Unit Recent Work Type of Lesson Sources Aims and Objectives Short Term Long TermDocument4 paginiDescription of Class Teaching Unit Recent Work Type of Lesson Sources Aims and Objectives Short Term Long TermJasmin IbrahimovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept Note UnhcrDocument6 paginiConcept Note Unhcrkassahun Mamo100% (1)

- Endorsement (ESIP)Document2 paginiEndorsement (ESIP)Farhen BlasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5e Shoe Lab Lesson PlanDocument3 pagini5e Shoe Lab Lesson Planapi-250608665Încă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Home Learning Plan - KindergartenDocument4 paginiWeekly Home Learning Plan - KindergartenGirlene Lobaton EstropeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Trained Dentists To US - FullDocument8 paginiForeign Trained Dentists To US - Fullh20pologt100% (1)

- Gate Pass - StudentsDocument1 paginăGate Pass - Studentsryan baile100% (1)

- The Official Study Guide For All SAT Subject TestsDocument1.051 paginiThe Official Study Guide For All SAT Subject TestsAUSTRAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Purposes of Classroom AssessmentDocument27 paginiPurposes of Classroom AssessmentPRINCESS JOY BUSTILLOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accessibility To The PHD and Professoriate For First-Generation College Graduates: Review and Implications For Students, Faculty, and Campus PoliciesDocument32 paginiAccessibility To The PHD and Professoriate For First-Generation College Graduates: Review and Implications For Students, Faculty, and Campus Policiesapi-26010865Încă nu există evaluări

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form SampleDocument6 paginiIndividual Performance Commitment and Review Form Samplecojilene71% (7)

- PGDTE Fee InfoDocument3 paginiPGDTE Fee Infosollu786_889163149Încă nu există evaluări

- Pagalguy Bschool RankingsDocument22 paginiPagalguy Bschool RankingsSunny GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Portfolio ResumeDocument3 paginiPortfolio Resumeapi-460126105Încă nu există evaluări

- Gifted and TalantedDocument48 paginiGifted and Talantedasadahmedonline0% (1)

- University of Wolverhampton PresentationDocument20 paginiUniversity of Wolverhampton PresentationttrbÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Week 2018Document2 paginiEnglish Week 2018suhaini abidinÎncă nu există evaluări

- MB Teaching ResumeDocument1 paginăMB Teaching Resumeapi-542517914Încă nu există evaluări

- Reference ListDocument7 paginiReference ListXin Yee WongÎncă nu există evaluări

- SET City and Guilds Courses Application Form Updated 4th December 2009Document4 paginiSET City and Guilds Courses Application Form Updated 4th December 2009gingernut337Încă nu există evaluări

- Pup Completion Form ADocument1 paginăPup Completion Form AJaynie Ahashine0% (1)

- Jacqueline Villeda ResumeDocument2 paginiJacqueline Villeda Resumeapi-438621255Încă nu există evaluări

- Edu-480 Week 4 Communication Skills NewsletterDocument3 paginiEdu-480 Week 4 Communication Skills Newsletterapi-458213504100% (3)

- ACSCU-Accrediting Agency 2011Document35 paginiACSCU-Accrediting Agency 2011Em TyÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Entrepreneurs Madam C. J Walker and The Studebaker Brothers Have Contributed To and Influenced Indiana and Our Local CommunityDocument17 paginiHow Entrepreneurs Madam C. J Walker and The Studebaker Brothers Have Contributed To and Influenced Indiana and Our Local Communityapi-220065957Încă nu există evaluări

- 6-8 Sa1 Date SheetDocument3 pagini6-8 Sa1 Date SheetRKS708Încă nu există evaluări

- Rioux ResumeDocument1 paginăRioux Resumeapi-320413952Încă nu există evaluări

- Reccomendation LetterDocument1 paginăReccomendation Letterapi-501250762Încă nu există evaluări