Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hyperglycemia During Total Parenteral Nutrition

Încărcat de

JennyLapitanDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hyperglycemia During Total Parenteral Nutrition

Încărcat de

JennyLapitanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Clinical Care/Education/Nutrition/Psychosocial Research

B R I E F

R E P O R T

Hyperglycemia During Total Parenteral

Nutrition

An important marker of poor outcome and mortality in hospitalized

patients

FRANCISCO J. PASQUEL, MD1

RONNIE SPIEGELMAN, PHD1

MEGAN MCCAULEY, MD1

DAWN SMILEY, MD1

DENISE UMPIERREZ, BA1

RACHEL JOHNSON, BA1

MARY RHEE, MD1

CHELSEA GATCLIFFE, BA1

ERICA LIN, BA1

ERICA UMPIERREZ1

LIMIN PENG, PHD2

GUILLERMO E. UMPIERREZ, MD1

OBJECTIVE To determine the effect of total parenteral nutrition (TPN)-induced hyperglycemia on hospital outcome.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS The study determined whether blood glucose values before, within 24 h, and during days 210 of TPN are predictive of hospital complications and mortality.

RESULTS Subjects included a total of 276 patients receiving TPN for a mean duration of

15 24 days (SD). In multiple regression models adjusted for age, sex, and diabetes status,

mortality was independently predicted by pre-TPN blood glucose of 121150 mg/dl (odds ratio

[OR] 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 4.4, P 0.030), 151180 mg/dl (3.41, 1.3 8.7, P 0.01), and 180

mg/dl (2.2, 0.9 5.2, P 0.077) and by blood glucose within 24 h of 180 mg/dl (2.8, 1.2 6.8,

P 0.020). A blood glucose within 24 h of 180 mg/dl was associated with increased risk of

pneumonia (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.4 7.1) and acute renal failure (2.3, 1.15.0).

CONCLUSIONS Hyperglycemia is associated with increased hospital complications and

mortality in patients receiving TPN.

Diabetes Care 33:739741, 2010

he beneficial effect of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) in improving

the nutrition status of hospitalized

malnourished patients is well established

(1). Recent randomized trials and metaanalyses, however, have raised questions

about its safety and the increased rate of

TPN-associated complications and mortality in critically ill patients (2 4). The

increased risk of complications during

TPN therapy can be related, among other

factors, to the development of hyperglycemia, which occurs in 10 88% of hospitalized patients receiving TPN therapy

(4 6). Despite the high frequency of

TPN-induced hyperglycemia, it is not

known if the severity of hyperglycemia

and/or the timing of hyperglycemia before initiation or during TPN therapy lead

to hospital complications. Accordingly,

we determined 1) the impact of TPNinduced hyperglycemia on survival and 2)

whether blood glucose value before,

shortly after initiation (within 24 h),

and/or during TPN therapy can serve as

predictive markers of in-hospital complications and mortality.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND

METHODS This work involved retrospective study of medical and surgical

patients receiving TPN during the period

From the 1Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia; and the 2Rollins

School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Corresponding author: Guillermo Umpierrez, geumpie@emory.edu.

Received 18 September 2009 and accepted 21 December 2009. Published ahead of print at http://care.

diabetesjournals.org on 29 December 2009. DOI: 10.2337/dc09-1748.

2010 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby

marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

care.diabetesjournals.org

of 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2006

at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta,

Georgia. Patients were managed after the

hospital TPN nutrition protocol aimed to

provide 2535 kcal kg1 day1 and

12 g protein kg1 day1. We collected

information on demographics; blood glucose on admission, pre-TPN, within 24 h,

and during days 210 of TPN; Acute

Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score; length of hospital

stay; hospital complications; and

mortality.

Data analysis

For comparison of baseline demographics

and clinical characteristics between

groups, we used two-sample Wilcoxons

tests for continuous variables and 2 test

for categorical variables with Bonferronis

corrections when applicable. Multiple logistic regression and adjusted odds ratios

(ORs) were used to determine the influence of clinical characteristics on mortality and complications. A P value of 0.05

was considered significant.

RESULTS The study population included 276 consecutive medical (33%)

and surgical (65%) patients (mean age

51 18 years, BMI 26 7 kg/m2, known

diabetes 19.2%, intensive care unit admission 78.2%). TPN was started 12 12

days after admission and was given for a

mean duration of 15 24 days.

The mean blood glucose level on admission was 139 85 mg/dl. The mean

blood glucose level before TPN was

123.2 33 mg/dl and increased to a

mean blood glucose of 146 44 mg/dl

within 24 h of TPN and remained elevated (147 40 mg/dl) during days 210

of TPN infusion (P 0.01 from baseline).

The overall hospital mortality was

27.2%. Deceased patients were older,

were more likely to be in the intensive

care unit, and had higher admission

APACHE II scores versus nondeceased

patients (all, P 0.01). Deceased patients

had a higher pre-TPN blood glucose

(129 37 vs. 121 32 mg/dl, P 0.08),

a higher blood glucose within 24 h

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, NUMBER 4, APRIL 2010

739

TPN-induced hyperglycemia and mortality

(162 55 vs. 139 37 mg/dl, P

0.003), and a higher blood glucose during

days 210 of TPN (161 53 vs. 142 34

mg/dl, P 0.013) than nondeceased

patients.

In multiple regression models adjusted for age, sex, and history of diabetes,

the likelihood of death was independently predicted by elevated pre-TPN

blood glucose between 121 and 150

mg/dl (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 4.4, P

0.030), 151 and 180 mg/dl (3.41, 1.3

8.7, P 0.010), and 180 mg/dl (2.2,

0.9 5.2, P 0.077) or by the blood glucose within 24 h 180 mg/dl (2.8, 1.2

6.8, P 0.020) versus patients with a

mean blood glucose 120 mg/dl. In multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex,

and history of diabetes, the blood glucose

within 24 h of TPN 180 mg/dl was associated with increased risk of pneumonia (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.6 8.4) and acute

renal failure (2.2, 1.02 4.8 1) compared

with patients with blood glucose 120

mg/dl. Patients with higher blood glucose

levels during TPN had a longer hospital

(P 0.011) and intensive care unit (P

0.008) length of stay.

CONCLUSIONS Malnutrition is

reported in up to 40% of critically ill patients (1,7) and is associated with increased risk of hospital complications,

longer hospital stay, and mortality (8).

Despite improving the nutrition state and

immunologic competence (9), TPN therapy has been associated with increased

risk for infections and mortality (2,10

13). The increased risk of complications

appears to be related, among other factors, to the development of hyperglycemia (4,14). Observational studies have

reported a 33% mortality rate in TPN patients who developed hyperglycemia

(15), as well as an increased risk of cardiac

complications, infections, systemic sepsis, and acute renal failure (3,4,6). In

agreement with these reports, we found a

strong correlation between TPN-induced

hyperglycemia and poor clinical outcome. Of interest, we observed that values

before and within 24 h of initiation of

TPN are better predictors of hospital mortality and complications than blood glucose during the entire duration of TPN

(Fig. 1).

In multiple regression models adjusted for age, sex, and diabetes status,

mortality was independently predicted by

pre-TPN blood glucose values between

151 and 180 mg/dl (OR 3.41, 95% CI

1.3 8.7, P 0.01) and 180 mg/dl (2.2,

740

Figure 1Mean blood glucose (BG) levels and mortality rate. , blood glucose levels pre-TPN

(BG Pre-TPN), P 0.167. f, blood glucose levels within 24 hours of TPN (BG-24h TPN), P

0.004. , blood glucose levels during days 210 of TPN (BG D210 of TPN), P 0.060.

0.9 5.2, P 0.077), as well as by blood

glucose within 24 h of TPN 180 mg/dl

(2.8, 1.2 6.8, P 0.020) versus patients

without hyperglycemia. In addition,

blood glucose 180 mg/dl within 24 h of

initiation of TPN was associated with increased risk of pneumonia (3.1, 1.4 7.1)

and acute renal failure (2.3, 1.15.0).

The mechanisms underlying the detrimental effects of hyperglycemia relate to

alterations in immune functions and inflammatory response (16,17). Hyperglycemia impairs leukocyte function,

phagocytosis, and chemotaxis (18). Hyperglycemia also increases counterregulatory hormones, inflammatory cytokines,

and oxidative stress (16,17), which can

lead to endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular complications (17). In addition to hyperglycemia, the administration

of Intralipid in TPN solutions may worsen

clinical outcome. Intralipid infusion, a

soybean oil-based emulsion rich in n-6

polyunsaturated fatty acids (19), has been

associated with exaggerated inflammatory response, immunosuppression, insulin resistance, increased blood pressure,

endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative

stress (19).

In summary, TPN-induced hyperglycemia is associated with increased length

of hospital stay, increased risk of complications, and higher mortality in hospitalized patients. Our study indicates that

blood glucose values before and within

24 h of initiation of TPN are better predictors of hospital mortality and compli-

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, NUMBER 4, APRIL 2010

cations than the mean blood glucose

during the entire duration of TPN. These

results suggest that early and aggressive

intervention to prevent and correct hyperglycemia may improve clinical outcome in patients receiving TPN.

Acknowledgments We appreciate the support of the Medical Records Department staff

at Grady Memorial Hospital. G.E.U. is supported by research grants from the American

Diabetes Association (7-03-CR-35) and the

National Institutes of Health (M01

RR-00039).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to

this article were reported.

This work was presented in abstract form at

the 69th Scientific Sessions, American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, Louisiana, 59

June 2009.

References

1. Ziegler TR. Parenteral nutrition in the critically ill patient. N Engl J Med 2009;361:

1088 1097

2. Heyland DK, Montalvo M, MacDonald S,

Keefe L, Su XY, Drover JW. Total parenteral nutrition in the surgical patient: a

meta-analysis. Can J Surg 2001;44:102

111

3. Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in

surgical patients. The Veterans Affairs Total Parenteral Nutrition Cooperative

Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991;325:

525532

4. der Voort PH, Feenstra RA, Bakker AJ,

Heide L, Boerma EC, der Horst IC. Intravenous glucose intake independently recare.diabetesjournals.org

Pasquel and Associates

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

lated to intensive care unit and hospital

mortality: an argument for glucose toxicity in critically ill patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:141145

Schloerb PR. Glucose in parenteral nutrition: a survey of U.S. medical centers.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2004;28:

447 452

Cheung NW, Napier B, Zaccaria C,

Fletcher JP. Hyperglycemia is associated

with adverse outcomes in patients receiving total parenteral nutrition. Diabetes

Care 2005;28:23672371

Giner M, Laviano A, Meguid MM, Gleason

JR. In 1995 a correlation between malnutrition and poor outcome in critically ill

patients still exists. Nutrition 1996;12:

2329

Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of

malnutrition on morbidity, mortality,

length of hospital stay and costs evaluated

through a multivariate model analysis.

Clin Nutr 2003;22:235239

McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW,

McCarthy M, Roberts P, Taylor B, Ochoa

JB, Napolitano L, Cresci G, A.S.P.E.N.

Board of Directors, American College of

Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical

Care Medicine. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support

care.diabetesjournals.org

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient:

Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM)

and American Society for Parenteral and

Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J

Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009;33:277316

Anderson AD, Jain PK, MacFie J. Parenteral nutrition in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:2103

Bellantone R, Doglietto G, Bossola M,

Pacelli F, Negro F, Sofo L, Crucitti F. Preoperative parenteral nutrition of malnourished surgical patients. Acta Chir

Scand 1988;154:249 251

Klein S, Kinney J, Jeejeebhoy K, Alpers

D, Hellerstein M, Murray M, Twomey P.

Nutrition support in clinical practice:

review of published data and recommendations for future research directions: summary of a conference sponsored by the National Institutes of

Health, American Society for Parenteral

and Enteral Nutrition, and American

Society for Clinical Nutrition. Am J Clin

Nutr 1997;66:683706

Marik PE. Death by total parenteral nutrition: part deux. Crit Care Med 2006;34:

3062

Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N,

You X, Thaler LM, Kitabchi AE. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

hospital mortality in patients with

undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 2002;87:978 982

Valero MA, Alegre E, Gomis P, Moreno

JM, Miguelez S, Leon-Sanz M. Clinical

management of hyperglycaemic patients

receiving total parenteral nutrition. Clin

Nutr 1996;15:1115

Kitabchi AE, Freire AX, Umpierrez GE.

Evidence for strict inpatient blood glucose control: time to revise glycemic goals

in hospitalized patients. Metabolism 2008;

57:116 120

Umpierrez GE, Kitabchi AE. ICU care for

patients with diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol 2004;11:75 81

Turina M, Fry DE, Polk HC Jr. Acute hyperglycemia and the innate immune system: clinical, cellular, and molecular

aspects. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1624

1633

Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Robalino G,

Peng L, Kitabchi AE, Khan B, Le A,

Quyyumi A, Brown V, Phillips LS. Intravenous intralipid-induced blood pressure

elevation and endothelial dysfunction in

obese African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:

609 614

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 33, NUMBER 4, APRIL 2010

741

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Cardiovascular Disease: A Case Presentation ofDocument2 paginiCardiovascular Disease: A Case Presentation ofJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Pi GlucophageDocument35 paginiPi GlucophageJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

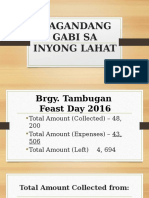

- Magandang Gabi Sa Inyong LahatDocument7 paginiMagandang Gabi Sa Inyong LahatJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Staffing? Definition and MeaningDocument4 paginiWhat Is Staffing? Definition and MeaningJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Discharge PlanDocument4 paginiDischarge PlanJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Nursing Care Plan (Peptic Ulcer)Document4 paginiNursing Care Plan (Peptic Ulcer)JennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Nine Principles For Improved Nurse Staffing by Bob DentDocument6 paginiNine Principles For Improved Nurse Staffing by Bob DentJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Nozinan Drug StudyDocument2 paginiNozinan Drug StudyJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Planning CharacteristicsDocument1 paginăPlanning CharacteristicsJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Primigravida : Obstetrical Outcome With Engaged Versus Unengaged Fetal Head With Spontaneous Onset of Labour at TermDocument6 paginiPrimigravida : Obstetrical Outcome With Engaged Versus Unengaged Fetal Head With Spontaneous Onset of Labour at TermJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- 5 Drug StudyDocument14 pagini5 Drug StudyJennyLapitan100% (2)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Lithium Carbonate Drug StudyDocument3 paginiLithium Carbonate Drug StudyJennyLapitan80% (5)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Generic Name:: Name of The Drug Mechanism of Action Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing ResponsibilitiesDocument8 paginiGeneric Name:: Name of The Drug Mechanism of Action Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing ResponsibilitiesJennyLapitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Health Implication and Complication of Herbal MedicineDocument26 paginiHealth Implication and Complication of Herbal Medicineigweonyia gabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community DentistryDocument3 paginiCommunity DentistryEkta Singh0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Acute Limb IschemicDocument14 paginiAcute Limb IschemicLuke FloydÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fecal Calprotectin in IBDDocument34 paginiFecal Calprotectin in IBDNathania Nadia Budiman100% (1)

- Cottenden - Wagg - Supplementary - 23551 ASW Edited Again PDFDocument74 paginiCottenden - Wagg - Supplementary - 23551 ASW Edited Again PDFrohiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Nursing BulletsDocument65 paginiNursing BulletsMark Anthony Esmundo RN100% (1)

- Episiotomía Desgarro PerinealDocument9 paginiEpisiotomía Desgarro PerinealjigagomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- KumarDocument5 paginiKumarMeris JugadorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Affirmation Surgery For The Treatment of Gender DysphoriaDocument4 paginiGender Affirmation Surgery For The Treatment of Gender DysphoriaJess Aloe100% (1)

- World Class Technology.: Results That Make A DifferenceDocument2 paginiWorld Class Technology.: Results That Make A DifferenceAndre ZeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perforasi Pada Penderita Apendisitis Di RSUD DR.H.Abdul Moeloek LampungDocument7 paginiPerforasi Pada Penderita Apendisitis Di RSUD DR.H.Abdul Moeloek LampungKikiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- UCSD Internal Medicine Handbook 2011Document142 paginiUCSD Internal Medicine Handbook 2011ak100007100% (5)

- AV Shunt-Brescia Cimino - EditDocument53 paginiAV Shunt-Brescia Cimino - EditYufriadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kathryn Vercillo - Internet AddictionDocument249 paginiKathryn Vercillo - Internet AddictionMarco MaiguaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6.2 Health Declaration Form - EmployeeDocument1 pagină6.2 Health Declaration Form - EmployeeyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Document 85Document51 paginiDocument 85Shameena AnwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knox ComplaintDocument16 paginiKnox ComplaintDan LehrÎncă nu există evaluări

- NUR 450 Medical Surgical Nursing II SyllabusDocument23 paginiNUR 450 Medical Surgical Nursing II SyllabusMohammad Malik0% (2)

- CPG Management of Diabetic Foot (2nd Ed)Document76 paginiCPG Management of Diabetic Foot (2nd Ed)Nokoline Hu100% (1)

- Surgical ICU Exam Content OutlineDocument6 paginiSurgical ICU Exam Content OutlineDarren DawkinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment of Dengue Joe de LiveraDocument11 paginiTreatment of Dengue Joe de Liverakrishna2205100% (1)

- Kode Nama Barang Stok Selling Price Disc: KemasanDocument9 paginiKode Nama Barang Stok Selling Price Disc: KemasanEny EndarwatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idiopathic Hypersomnia Its All in Their HeadDocument2 paginiIdiopathic Hypersomnia Its All in Their HeadSambo Pembasmi LemakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmaceutical Biotechnology-QBDocument8 paginiPharmaceutical Biotechnology-QBprateekshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 4 Bio Lab 7/28/2012Document2 paginiWeek 4 Bio Lab 7/28/2012KT100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Shadowing JournalDocument5 paginiShadowing Journalapi-542121685Încă nu există evaluări

- Multiple MyelomaDocument2 paginiMultiple MyelomaKolin JandocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Assessment Form - BHERTDocument2 paginiHealth Assessment Form - BHERTPoblacion 04 San LuisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 3 - Internet Addiction: Activity 1 - Pre-Learn VocabularyDocument8 paginiLesson 3 - Internet Addiction: Activity 1 - Pre-Learn VocabularyLyon WooÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2022 Intensive Course. MM - Viral Hepatitis & HIV - AP Datin DR Noor ZettiDocument65 pagini2022 Intensive Course. MM - Viral Hepatitis & HIV - AP Datin DR Noor ZettiRaja RuzannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookDe la EverandInstant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)