Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Persons and Family Relations Cases

Încărcat de

Maree Aiko Dawn LipatTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Persons and Family Relations Cases

Încărcat de

Maree Aiko Dawn LipatDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

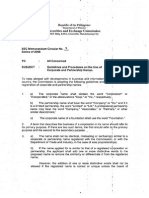

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No.

11 Page 1

G.R. No. 116668 July 28, 1997

ERLINDA A. AGAPAY, petitioner,

vs.

CARLINA (CORNELIA) V. PALANG and HERMINIA P. DELA

CRUZ, respondents.

Family Code; Husband and Wife; Cohabitation; Co-Ownership; Under Article 148

of the Family Code, only the properties acquired by both of the parties through their

actual joint contribution of money, property or industry shall be owned by them in

common in proportion to their respective contributions.The sale of the riceland on

May 17, 1973, was made in favor of Miguel and Erlinda. The provision of law

applicable here is Article 148 of the Family Code providing for cases of cohabitation

when a man and a woman who are not capacitated to marry each other live

exclusively with each other as husband and wife without the benefit of marriage or

under a void marriage. While Miguel and Erlinda contracted marriage on July 15,

1973, said union was patently void because the earlier marriage of Miguel and

Carlina was still subsisting and unaffected by the latters de facto separation. Under

Article 148, only the properties acquired by both of the parties through their actual

joint contribution of money, property or industry shall be owned by them in common

in proportion to their respective contributions. It must be stressed that actual

contribution is required by this provision, in contrast to Article 147 which states that

efforts in the care and maintenance of the family and household, are regarded as

contributions to the acquisition of common property by one who has no salary or

income or work or industry. If the actual contribution of the party is not proved, there

will be no co-ownership and no presumption of equal shares.

Same; Same; Same; Same; Considering the youthfulness of the woman, she being

only twenty years of age then, while the man she cohabited with was already sixtyfour and a pensioner of the U.S. Government, it is unrealistic to conclude that in

1973 she contributed P3,750.00 as her share in the purchase price of a parcel of land,

there being no proof of the same.In the case at bar, Erlinda tried to establish by her

testimony that she is engaged in the business of buy and sell and had a sari-sari store

but failed to persuade us that she actually contributed money to buy the subject

riceland. Worth noting is the fact that on the date of conveyance, May 17, 1973,

petitioner was only around twenty years of age and Miguel Palang was already sixtyfour and a pensioner of the U.S. Government. Considering her youthfulness, it is

unrealistic to conclude that in 1973 she contributed P3,750.00 as her share in the

purchase price of subject property, there being no proof of the same.

Same; Same; Same; Same; Where a woman who cohabited with a married man fails

to prove that she contributed money to the purchase price of a riceland, there is no

basis to justify her co-ownership over the samethe riceland should revert to the

conjugal partnership property of the man and his lawful wife.Since petitioner

failed to prove that she contributed money to the purchase price of the riceland in

Binalonan, Pangasinan, we find no basis to justify her co-ownership with Miguel

over the same. Consequently, the riceland should, as correctly held by the Court of

Appeals, revert to the conjugal partnership property of the deceased Miguel and

private respondent Carlina Palang.

Same; Same; Same; Separation of Property; Compromise Agreements; Separation of

property between spouses during the marriage shall not take place except by judicial

order or, without judicial conferment, when there is an express stipulation in the

marriage settlement; Where the judgment which resulted from the parties

compromise was not specifically and expressly for separation of property, the same

should not be so inferred as judicial confirmation of separation of property.

Furthermore, it is immaterial that Miguel and Carlina previously agreed to donate

their conjugal property in favor of their daughter Herminia in 1975. The trial court

erred in holding that the decision adopting their compromise agreement in effect

partakes the nature of judicial confirmation of the separation of property between

spouses and the termination of the conjugal partnership. Separation of property

between spouses during the marriage shall not take place except by judicial order or

without judicial conferment when there is an express stipulation in the marriage

settlements. The judgment which resulted from the parties compromise was not

specifically and expressly for separation of property and should not be so inferred.

Same; Same; Same; Donations; The prohibition against donations between spouses

applies to donations between persons living together as husband and wife without a

valid marriage.With respect to the house and lot, Erlinda allegedly bought the

same for P20,000.00 on September 23, 1975 when she was only 22 years old. The

testimony of the notary public who prepared the deed of conveyance for the property

reveals the falsehood of this claim. Atty. Constantino Sagun testified that Miguel

Palang provided the money for the purchase price and directed that Erlindas name

alone be placed as the vendee. The transaction was properly a donation made by

Miguel to Erlinda, but one which was clearly void and inexistent by express

provision of law because it was made between persons guilty of adultery or

concubinage at the time of the donation, under Article 739 of the Civil Code.

Moreover, Article 87 of the Family Code expressly provides that the prohibition

against donations between spouses now applies to donations between persons living

together as husband and wife without a valid marriage, for otherwise, the condition

of those who incurred guilt would turn out to be better than those in legal union.

Same; Same; Same; Parent and Child; Illegitimate Children; Filiation; Succession;

Probate Proceedings; Questions as to who are the heirs of the decedent, proof of

filiation of illegitimate children and the determination of the estate of the latter and

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 2

claims thereto should be ventilated in the proper probate court or in a special

proceeding instituted for the purpose and cannot be adjudicated in an ordinary civil

action for recovery of ownership and possession.The second issue concerning

Kristopher Palangs status and claim as an illegitimate son and heir to Miguels estate

is here resolved in favor of respondent courts correct assessment that the trial court

erred in making pronouncements regarding Kristophers heirship and filiation

inasmuch as questions as to who are the heirs of the decedent, proof of filiation of

illegitimate children and the determination of the estate of the latter and claims

thereto should be ventilated in the proper probate court or in a special proceeding

instituted for the purpose and cannot be adjudicated in the instant ordinary civil

action which is for recovery of ownership and possession.

Same; Same; Same; Same; Actions; Pleadings and Practice; Parties; Guardians; A

minor who has not been impleaded is not a party to the case and neither can his

mother be called guardian ad litem.As regards the third issue, petitioner contends

that Kristopher Palang should be considered as party-defendant in the case at bar

following the trial courts decision which expressly found that Kristopher had not

been impleaded as party defendant but theorized that he had submitted to the courts

jurisdiction through his mother/guardian ad litem. The trial court erred gravely.

Kristopher, not having been impleaded, was, therefore, not a party to the case at bar.

His mother, Erlinda, cannot be called his guardian ad litem for he was not involved

in the case at bar. Petitioner adds that there is no need for Kristopher to file another

action to prove that he is the illegitimate son of Miguel, in order to avoid multiplicity

of suits. Petitioners grave error has been discussed in the preceding paragraph where

the need for probate proceedings to resolve the settlement of Miguels estate and

Kristophers successional rights has been pointed out.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Simplicio M. Sevilleja for petitioner.

Ray L. Basbas and Fe Fernandez-Bautista for private respondents.

acquired during the cohabitation of petitioner and private respondent's legitimate

spouse.

Miguel Palang contracted his first marriage on July 16, 1949 when he took private

respondent Carlina (or Cornelia) Vallesterol as a wife at the Pozorrubio Roman

Catholic Church in Pangasinan. A few months after the wedding, in October 1949, he

left to work in Hawaii. Miguel and Carlina's only child, Herminia Palang, was born

on May 12, 1950.

Miguel returned in 1954 for a year. His next visit to the Philippines was in 1964 and

during the entire duration of his year-long sojourn he stayed in Zambales with his

brother, not in Pangasinan with his wife and child. The trial court found evidence that

as early as 1957, Miguel had attempted to divorce Carlina in Hawaii. 1 When he

returned for good in 1972, he refused to live with private respondents, but stayed

alone in a house in Pozorrubio, Pangasinan.

On July 15, 1973, the then sixty-three-year-old Miguel contracted his second

marriage with nineteen-year-old Erlinda Agapay, herein petitioner. 2 Two months

earlier, on May 17, 1973, Miguel and Erlinda, as evidenced by the Deed of Sale,

jointly purchased a parcel of agricultural land located at San Felipe, Binalonan,

Pangasinan with an area of 10,080 square meters. Consequently, Transfer Certificate

of Title No. 101736 covering said rice land was issued in their names.

A house and lot in Binalonan, Pangasinan was likewise purchased on September 23,

1975, allegedly by Erlinda as the sole vendee. TCT No. 143120 covering said

property was later issued in her name.

On October 30, 1975, Miguel and Cornelia Palang executed a Deed of Donation as a

form of compromise agreement to settle and end a case filed by the latter. 3 The

parties therein agreed to donate their conjugal property consisting of six parcels of

land to their only child, Herminia Palang. 4

Miguel and Erlinda's cohabitation produced a son, Kristopher A. Palang, born on

December 6, 1977. In 1979, Miguel and Erlinda were convicted of Concubinage

upon Carlina's complaint. 5 Two years later, on February 15, 1981, Miguel died.

[Agapay vs. Palang, 276 SCRA 340, G.R. No. 116668 July 28, 1997]

ROMERO, J.:

Before us is a petition for review of the decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R.

CV No. 24199 entitled "Erlinda Agapay v. Carlina (Cornelia) Palang and Herminia P.

Dela Cruz" dated June 22, 1994 involving the ownership of two parcels of land

On July 11, 1981, Carlina Palang and her daughter Herminia Palang de la Cruz,

herein private respondents, instituted the case at bar, an action for recovery of

ownership and possession with damages against petitioner before the Regional Trial

Court in Urdaneta, Pangasinan (Civil Case No. U-4265). Private respondents sought

to get back the riceland and the house and lot both located at Binalonan, Pangasinan

allegedly purchased by Miguel during his cohabitation with petitioner.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 3

Petitioner, as defendant below, contended that while the riceland covered by TCT

No. 101736 is registered in their names (Miguel and Erlinda), she had already given

her half of the property to their son Kristopher Palang. She added that the house and

lot covered by TCT No. 143120 is her sole property, having bought the same with

her own money. Erlinda added that Carlina is precluded from claiming aforesaid

properties since the latter had already donated their conjugal estate to Herminia.

After trial on the merits, the lower court rendered its decision on June 30, 1989

dismissing the complaint after declaring that there was little evidence to prove that

the subject properties pertained to the conjugal property of Carlina and Miguel

Palang. The lower court went on to provide for the intestate shares of the parties,

particularly of Kristopher Palang, Miguel's illegitimate son. The dispositive portion

of the decision reads.

WHEREFORE,

rendered

premises

considered,

judgment

is

hereby

On appeal, respondent court reversed the trial court's decision. The Court of Appeals

rendered its decision on July 22, 1994 with the following dispositive portion;

WHEREFORE, PREMISES CONSIDERED, the appealed decision in

hereby REVERSED and another one entered:

1. Declaring plaintiffs-appellants the owners of the properties in question;

2. Ordering defendant-appellee to vacate and deliver the properties in

question to herein plaintiffs-appellants;

3. Ordering the Register of Deeds of Pangasinan to cancel Transfer

Certificate of Title Nos. 143120 and 101736 and to issue in lieu thereof

another certificate of title in the name of plaintiffs-appellants.

No pronouncement as to costs. 7

1) Dismissing the complaint, with costs against plaintiffs;

Hence, this petition.

2) Confirming the ownership of defendant Erlinda Agapay of the residential

lot located at Poblacion, Binalonan, Pangasinan, as evidenced by TCT No.

143120, Lot 290-B including the old house standing therein;

Petitioner claims that the Court of Appeals erred in not sustaining the validity of two

deeds of absolute sale covering the riceland and the house and lot, the first in favor

of Miguel Palang and Erlinda Agapay and the second, in favor of Erlinda Agapay

alone. Second, petitioner contends that respondent appellate court erred in not

declaring Kristopher A. Palang as Miguel Palang's illegitimate son and thus entitled

to inherit from Miguel's estate. Third, respondent court erred, according to petitioner,

"in not finding that there is sufficient pleading and evidence that Kristopher A.

Palang or Christopher A. Palang should be considered as party-defendant in Civil

Case No. U-4625 before the trial court and in CA-G.R. No. 24199. 8

3) Confirming the ownership of one-half (1/2) portion of that piece of

agricultural land situated at Balisa, San Felipe, Binalonan, Pangasinan,

consisting of 10,080 square meters and as evidenced by TCT No. 101736,

Lot 1123-A to Erlinda Agapay;

4. Adjudicating to Kristopher Palang as his inheritance from his deceased

father, Miguel Palang, the one-half (1/2) of the agricultural land situated at

Balisa, San Felipe, Binalonan, Pangasinan, under TCT No. 101736 in the

name of Miguel Palang, provided that the former (Kristopher) executes,

within 15 days after this decision becomes final and executory, a quit-claim

forever renouncing any claims to annul/reduce the donation to Herminia

Palang de la Cruz of all conjugal properties of her parents, Miguel Palang

and Carlina Vallesterol Palang, dated October 30, 1975, otherwise, the

estate of deceased Miguel Palang will have to be settled in another separate

action;

5) No pronouncement as to damages and attorney's fees.

SO ORDERED. 6

After studying the merits of the instant case, as well as the pertinent provisions of

law and jurisprudence, the Court denies the petition and affirms the questioned

decision of the Court of Appeals.

The first and principal issue is the ownership of the two pieces of property subject of

this action. Petitioner assails the validity of the deeds of conveyance over the same

parcels of land. There is no dispute that the transfer of ownership from the original

owners of the riceland and the house and lot, Corazon Ilomin and the spouses

Cespedes, respectively, were valid.

The sale of the riceland on May 17, 1973, was made in favor of Miguel and Erlinda.

The provision of law applicable here is Article 148 of the Family Code providing for

cases of cohabitation when a man and a woman who are not capacitated to marry

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 4

each other live exclusively with each other as husband and wife without the benefit

of marriage or under a void marriage. While Miguel and Erlinda contracted marriage

on July 15, 1973, said union was patently void because the earlier marriage of

Miguel and Carlina was still subsisting and unaffected by the latter's de

facto separation.

Under Article 148, only the properties acquired by both of the parties through

their actual joint contribution of money, property or industry shall be owned by them

in common in proportion to their respective contributions. It must be stressed that

actual contribution is required by this provision, in contrast to Article 147 which

states that efforts in the care and maintenance of the family and household, are

regarded as contributions to the acquisition of common property by one who has no

salary or income or work or industry. If the actual contribution of the party is not

proved, there will be no co-ownership and no presumption of equal shares. 9

In the case at bar, Erlinda tried to establish by her testimony that she is engaged in

the business of buy and sell and had a sari-sari store 10 but failed to persuade us that

she actually contributed money to buy the subject riceland. Worth noting is the fact

that on the date of conveyance, May 17, 1973, petitioner was only around twenty

years of age and Miguel Palang was already sixty-four and a pensioner of the U.S.

Government. Considering her youthfulness, it is unrealistic to conclude that in 1973

she contributed P3,750.00 as her share in the purchase price of subject

property, 11 there being no proof of the same.

Petitioner now claims that the riceland was bought two months before Miguel and

Erlinda actually cohabited. In the nature of an afterthought, said added assertion was

intended to exclude their case from the operation of Article 148 of the Family Code.

Proof of the precise date when they commenced their adulterous cohabitation not

having been adduced, we cannot state definitively that the riceland was purchased

even before they started living together. In any case, even assuming that the subject

property was bought before cohabitation, the rules of co-ownership would still apply

and proof of actual contribution would still be essential.

Since petitioner failed to prove that she contributed money to the purchase price of

the riceland in Binalonan, Pangasinan, we find no basis to justify her co-ownership

with Miguel over the same. Consequently, the riceland should, as correctly held by

the Court of Appeals, revert to the conjugal partnership property of the deceased

Miguel and private respondent Carlina Palang.

Furthermore, it is immaterial that Miguel and Carlina previously agreed to donate

their conjugal property in favor of their daughter Herminia in 1975. The trial court

erred in holding that the decision adopting their compromise agreement "in effect

partakes the nature of judicial confirmation of the separation of property between

spouses and the termination of the conjugal partnership." 12 Separation of property

between spouses during the marriage shall not take place except by judicial order or

without judicial conferment when there is an express stipulation in the marriage

settlements. 13 The judgment which resulted from the parties' compromise was not

specifically and expressly for separation of property and should not be so inferred.

With respect to the house and lot, Erlinda allegedly bought the same for P20,000.00

on September 23, 1975 when she was only 22 years old. The testimony of the notary

public who prepared the deed of conveyance for the property reveals the falsehood of

this claim. Atty. Constantino Sagun testified that Miguel Palang provided the money

for the purchase price and directed that Erlinda's name alone be placed as the

vendee. 14

The transaction was properly a donation made by Miguel to Erlinda, but one which

was clearly void and inexistent by express provision of law because it was made

between persons guilty of adultery or concubinage at the time of the donation, under

Article 739 of the Civil Code. Moreover, Article 87 of the Family Code expressly

provides that the prohibition against donations between spouses now applies to

donations between persons living together as husband and wife without a valid

marriage, 15 for otherwise, the condition of those who incurred guilt would turn out to

be better than those in legal union. 16

The second issue concerning Kristopher Palang's status and claim as an illegitimate

son and heir to Miguel's estate is here resolved in favor of respondent court's correct

assessment that the trial court erred in making pronouncements regarding

Kristopher's heirship and filiation "inasmuch as questions as to who are the heirs of

the decedent, proof of filiation of illegitimate children and the determination of the

estate of the latter and claims thereto should be ventilated in the proper probate court

or in a special proceeding instituted for the purpose and cannot be adjudicated in the

instant ordinary civil action which is for recovery of ownership and possession." 17

As regards the third issue, petitioner contends that Kristopher Palang should be

considered as party-defendant in the case at bar following the trial court's decision

which expressly found that Kristopher had not been impleaded as party defendant but

theorized that he had submitted to the court's jurisdiction through his

mother/guardian ad litem. 18 The trial court erred gravely. Kristopher, not having been

impleaded, was, therefore, not a party to the case at bar. His mother, Erlinda cannot

be called his guardian ad litem for he was not involved in the case at bar. Petitioner

adds that there is no need for Kristopher to file another action to prove that he is

illegitimate son of Miguel, in order to avoid multiplicity of suits. 19 Petitioner's grave

error has been discussed in the preceding paragraph where the need for probate

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 5

proceedings to resolve the settlement of Miguel's estate and Kristopher's successional

rights has been pointed out.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is hereby DENIED. The questioned decision of

the Court of Appeals is AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

way of giving such child of tender age full protection.In a habeas corpus

proceeding involving the welfare and custody of a child of tender age, the paramount

concern is to resolve immediately the issue of who has legal custody of the child.

Technicalities should not stand in the way of giving such child of tender age full

protection. This rule has sound statutory basis in Article 213 of the Family Code,

which states, No child under seven years of age shall be separated from the mother

unless the court finds compelling reasons to order otherwise.

PETITION for review on certiorari of the resolutions of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Agripino C. Baybay III for petitioner.

Bridie O. Castronuevo for respondent.

[Tribiana vs. Tribiana, 438 SCRA 216, G.R. No. 137359 September 13, 2004]

DECISION

G.R. No. 137359

September 13, 2004

EDWIN N. TRIBIANA, petitioner,

vs.

LOURDES M. TRIBIANA, respondent

Remedial Law; Dismissal of Actions; A dismissal under Section 1(j) of Rule 16 is

warranted only if there is a failure to comply with a condition precedent. Given that

the alleged defect is a mere failure to allege compliance with a condition precedent,

the proper solution is not an outright dismissal of the action, but an amendment

under Section 1 of Rule 10 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure.A dismissal under

Section 1(j) of Rule 16 is warranted only if there is a failure to comply with a

condition precedent. Given that the alleged defect is a mere failure to allege

compliance with a condition precedent, the proper solution is not an outright

dismissal of the action, but an amendment under Section 1 of Rule 10 of the 1997

Rules of Civil Procedure. It would have been a different matter if Edwin had asserted

that no efforts to arrive at a compromise have been made at all.

Same; Habeas Corpus; In a habeas corpus proceeding involving the welfare and

custody of a child of tender age, the paramount concern is to resolve immediately the

issue of who has the legal custody of the child. Technicalities should not stand in the

CARPIO, J.:

The Case

This petition for review on certiorari 1 seeks to reverse the Court of Appeals

Resolutions2 dated 2 July 1998 and 18 January 1999 in CA-G.R. SP No. 48049. The

Court of Appeals affirmed the Order3 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 19, Bacoor,

Cavite ("RTC"), denying petitioner Edwin N. Tribianas ("Edwin") motion to dismiss

the petition for habeas corpus filed against him by respondent Lourdes Tribiana

("Lourdes").

Antecedent Facts

Edwin and Lourdes are husband and wife who have lived together since 1996 but

formalized their union only on 28 October 1997. On 30 April 1998, Lourdes filed a

petition for habeas corpus before the RTC claiming that Edwin left their conjugal

home with their daughter, Khriza Mae Tribiana ("Khriza"). Edwin has since deprived

Lourdes of lawful custody of Khriza who was then only one (1) year and four (4)

months of age. Later, it turned out that Khriza was being held by Edwins mother,

Rosalina Tribiana ("Rosalina"). Edwin moved to dismiss Lourdes petition on the

ground that the petition failed to allege that earnest efforts at a compromise were

made before its filing as required by Article 151 of the Family Code.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 6

On 20 May 1998, Lourdes filed her opposition to Edwins motion to dismiss

claiming that there were prior efforts at a compromise, which failed. Lourdes

attached to her opposition a copy of the Certification to File Action from their

Barangay dated 1 May 1998.

On 18 May 1998, the RTC denied Edwins motion to dismiss and reiterated a

previous order requiring Edwin and his mother, Rosalina to bring Khriza before the

RTC. Upon denial of his motion for reconsideration, Edwin filed with the Court of

Appeals a petition for prohibition and certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Civil

Procedure. The appellate court denied Edwins petition on 2 July 1998. The appellate

court also denied Edwins motion for reconsideration.

Hence, this petition.

The Rulings of the RTC and the Court of Appeals

The RTC denied Edwins motion to dismiss on the ground that the Certification to

File Action attached by Lourdes to her opposition clearly indicates that the parties

attempted to reach a compromise but failed.

The Court of Appeals upheld the ruling of the RTC and added that under Section 412

(b) (2) of the Local Government Code, conciliation proceedings before the barangay

are not required in petitions for habeas corpus.

The Issue

Edwin seeks a reversal and raises the following issue for resolution:

WHETHER THE TRIAL AND APPELLATE COURTS SHOULD HAVE

DISMISSED THE PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS ON THE

GROUND OF FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THE CONDITION

PRECEDENT UNDER ARTICLE 151 OF THE FAMILY CODE.

The Ruling of the Court

The petition lacks merit.

Edwin argues that Lourdes failure to indicate in her petition for habeas corpus that

the parties exerted prior efforts to reach a compromise and that such efforts failed is a

ground for the petitions dismissal under Section 1(j), Rule 16 of the 1997 Rules of

Civil Procedure.4 Edwin maintains that under Article 151 of the Family Code, an

earnest effort to reach a compromise is an indispensable condition precedent. Article

151 provides:

No suit between members of the same family shall prosper unless it should

appear from the verified complaint or petition that earnest efforts toward a

compromise have been made, but that the same have failed. If it is shown

that no such efforts were in fact made, the case must be dismissed.

This rule shall not apply to cases which may not be the subject of compromise under

the Civil Code.

Edwins arguments do not persuade us.

It is true that the petition for habeas corpus filed by Lourdes failed to allege that she

resorted to compromise proceedings before filing the petition. However, in her

opposition to Edwins motion to dismiss, Lourdes attached a Barangay Certification

to File Action dated 1 May 1998. Edwin does not dispute the authenticity of the

Barangay Certification and its contents. This effectively established that the parties

tried to compromise but were unsuccessful in their efforts. However, Edwin would

have the petition dismissed despite the existence of the Barangay Certification,

which he does not even dispute.

Evidently, Lourdes has complied with the condition precedent under Article 151 of

the Family Code. A dismissal under Section 1(j) of Rule 16 is warranted only if there

is a failure to comply with a condition precedent. Given that the alleged defect is a

mere failure to allege compliance with a condition precedent, the proper solution is

not an outright dismissal of the action, but an amendment under Section 1 of Rule 10

of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. 5 It would have been a different matter if Edwin

had asserted that no efforts to arrive at a compromise have been made at all.

In addition, the failure of a party to comply with a condition precedent is not a

jurisdictional defect.6 Such defect does not place the controversy beyond the courts

power to resolve. If a party fails to raise such defect in a motion to dismiss, such

defect is deemed waived.7 Such defect is curable by amendment as a matter of right

without leave of court, if made before the filing of a responsive pleading. 8 A motion

to dismiss is not a responsive pleading. 9 More importantly, an amendment alleging

compliance with a condition precedent is not a jurisdictional matter. Neither does it

alter the cause of action of a petition for habeas corpus. We have held that in cases

where the defect consists of the failure to state compliance with a condition

precedent, the trial court should order the amendment of the complaint. 10 Courts

should be liberal in allowing amendments to pleadings to avoid multiplicity of suits

and to present the real controversies between the parties.11

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 7

Moreover, in a habeas corpus proceeding involving the welfare and custody of a

child of tender age, the paramount concern is to resolve immediately the issue of

who has legal custody of the child. Technicalities should not stand in the way of

giving such child of tender age full protection.12 This rule has sound statutory basis in

Article 213 of the Family Code, which states, "No child under seven years of age

shall be separated from the mother unless the court finds compelling reasons to order

otherwise." In this case, the child (Khriza) was only one year and four months when

taken away from the mother.

The Court of Appeals dismissed Edwins contentions by citing as an additional

ground the exception in Section 412 (b) (2) of the Local Government Code ("LGC")

on barangay conciliation, which states:

(b) Where the parties may go directly to court. the parties may go directly

to court in the following instances:

xxx

2) Where a person has otherwise been deprived of personal liberty

calling for habeas corpusproceedings;

xxx.

Under Rule 102 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, a party may resort to

a habeas corpus proceeding in two instances. The first is when any person

is deprived of liberty either through illegal confinement or through

detention. The second instance is when custody of any person is withheld

from the person entitled to such custody. The most common case falling

under the second instance involves children who are taken away from a

parent by another parent or by a relative. The case filed by Lourdes falls

under this category.

The barangay conciliation requirement in Section 412 of the LGC does not apply

to habeas corpus proceedings where a person is "deprived of personal liberty." In

such a case, Section 412 expressly authorizes the parties "to go directly to court"

without need of any conciliation proceedings. There is deprivation of personal liberty

warranting a petition for habeas corpus where the "rightful custody of any person is

withheld from the person entitled thereto."13 Thus, the Court of Appeals did not err

when it dismissed Edwins contentions on the additional ground that Section 412

exempts petitions for habeas corpus from the barangay conciliation requirement.

The petition for certiorari filed by Edwin questioning the RTCs denial of his motion

to dismiss merely states a blanket allegation of "grave abuse of discretion." An order

denying a motion to dismiss is interlocutory and is not a proper subject of a petition

for certiorari.14 Even in the face of an error of judgment on the part of a judge

denying the motion to dismiss, certiorari will not lie. Certiorari is not a remedy to

correct errors of procedure.15 The proper remedy against an order denying a motion

to dismiss is to file an answer and interpose as affirmative defenses the objections

raised in the motion to dismiss. It is only in the presence of extraordinary

circumstances evincing a patent disregard of justice and fair play where resort to a

petition for certiorari is proper.16

The litigation of substantive issues must not rest on a prolonged contest on

technicalities. This is precisely what has happened in this case. The circumstances

are devoid of any hint of the slightest abuse of discretion by the RTC or the Court of

Appeals. A party must not be allowed to delay litigation by the sheer expediency of

filing a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 based on scant allegations of grave

abuse. More importantly, any matter involving the custody of a child of tender age

deserves immediate resolution to protect the childs welfare.

WHEREFORE, we DISMISS the instant petition for lack of merit.

We AFFIRM the Resolutions of the Court of Appeals dated 2 July 1998 and 18

January 1999 in CA-G.R. SP No. 48049. The Regional Trial Court, Branch 19,

Bacoor, Cavite is ordered to act with dispatch in resolving the petition for habeas

corpus pending before it. This decision is IMMEDIATELY EXECUTORY.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., Quisumbing, Ynares-Santiago, and Azcuna, JJ., concur.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 8

vs.

HON. COURT OF APPEALS, HON. REGIONAL TRIAL COURT OF

MANILA (BRANCH 35), PURITA S. JAYME, MILAGROS M. TERRE,

BELEN M. ORILLANO, ROSALINA M. ACUIN, ROMEO S. MANALO,

ROBERTO S. MANALO, AMALIA MANALO and IMELDA

MANALO, respondents.

Pleadings and Practice; Estate Proceedings; Probate Courts; It is a fundamental rule

that, in the determination of the nature of an action or proceeding, the averments and

the character of the relief sought in the complaint, or petition, shall be controlling;

The fact of death of the decedent and of his residence within the country are

foundation facts upon which all the subsequent proceedings in the administration of

the estate rest.It is a fundamental rule that, in the determination of the nature of an

action or proceeding, the averments and the character of the relief sought in the

complaint, or petition, as in the case at bar, shall be controlling. A careful scrutiny of

the Petition for Issuance of Letters of Administration, Settlement and Distribution of

Estate in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 belies herein petitioners claim that the same is in

the nature of an ordinary civil action. The said petition contains sufficient

jurisdictional facts required in a petition for the settlement of estate of a deceased

person such as the fact of death of the late Troadio Manalo on February 14, 1992, as

well as his residence in the City of Manila at the time of his said death. The fact of

death of the decedent and of his residence within the country are foundation facts

upon which all the subsequent proceedings in the administration of the estate rest.

The petition in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 also contains an enumeration of the names

of his legal heirs including a tentative list of the properties left by the deceased which

are sought to be settled in the probate proceedings. In addition, the reliefs prayed for

in the said petition leave no room for doubt as regard the intention of the petitioners

therein (private respondents herein) to seek judicial settlement of the estate of their

deceased father, Troadio Manalo.

G.R. NO. 129242

January 16, 2001

PILAR S. VDA. DE MANALO, ANTONIO S. MANALO, ORLANDO S.

MANALO, and ISABELITA MANALO ,petitioners,

Same; Same; Same; A party may not be allowed to defeat the purpose of an

essentially valid petition for the settlement of the estate of a decedent by raising

matters that are irrelevant and immaterial to the said petition; A trial court, sitting as

a probate court, has limited and special jurisdiction and cannot hear and dispose of

collateral matters and issues which may be properly threshed out only in an ordinary

civil action.It is our view that herein petitioners may not be allowed to defeat the

purpose of the essentially valid petition for the settlement of the estate of the late

Troadio Manalo by raising matters that are irrelevant and immaterial to the said

petition. It must be emphasized that the trial court, sitting as a probate court, has

limited and special jurisdiction and cannot hear and dispose of collateral matters and

issues which may be properly threshed out only in an ordinary civil action. In

addition, the rule has always been to the effect that the jurisdiction of a court, as well

as the concomitant nature of an action, is determined by the averments in the

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 9

complaint and not by the defenses contained in the answer. If it were otherwise, it

would not be too difficult to have a case either thrown out of court or its proceedings

unduly delayed by simple strategem. So it should be in the instant petition for

settlement of estate.

Same; Same; Same; Motion to Dismiss; A party may not take refuge under the

provisions of Rule 1, Section 2, of the Rules of Court to justify an invocation of

Article 222 of the Civil Code for the dismissal of a petition for settlement of estate.

The argument is misplaced. Herein petitioners may not validly take refuge under

the provisions of Rule 1, Section 2, of the Rules of Court to justify the invocation of

Article 222 of the Civil Code of the Philippines for the dismissal of the petition for

settlement of the estate of the deceased Troadio Manalo inasmuch as the latter

provision is clear enough, to wit: Art. 222. No suit shall be filed or maintained

between members of the same family unless it should appear that earnest efforts

toward a compromise have been made, but that the same have failed, subject to the

limitations in Article 2035.

Same; Same; Article 222 of the Civil Code applies only to civil actions which are

essentially adversarial and involve members of the same family.The above-quoted

provision of the law is applicable only to ordinary civil actions. This is clear from the

term suit that it refers to an action by one person or persons against another or

others in a court of justice in which the plaintiff pursues the remedy which the law

affords him for the redress of an injury or the enforcement of a right, whether at law

or in equity. A civil action is thus an action filed in a court of justice, whereby a party

sues another for the enforcement of a right, or the prevention or redress of a wrong.

Besides, an excerpt from the Report of the Code Commission unmistakably reveals

the intention of the Code Commission to make that legal provision applicable only to

civil actions which are essentially adversarial and involve members of the same

family, thus: It is difficult to imagine a sadder and more tragic spectacle than a

litigation between members of the same family. It is necessary that every effort

should be made toward a compromise before a litigation is allowed to breed hate and

passion in the family. It is known that lawsuit between close relatives generates

deeper bitterness than strangers.

Same; Same; Special Proceedings; A petition for issuance of letters of administration,

settlement and distribution of estate is a special proceeding and, as such, it is a

remedy whereby the petitioner therein seek to establish a status, a right, or a

particular fact.It must be emphasized that the oppositors (herein petitioners) are

not being sued in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 for any cause of action as in fact no

defendant was impleaded therein. The Petition for Issuance of Letters of

Administration, Settlement and Distribution of Estate in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 is

a special proceeding and, as such, it is a remedy whereby the petitioners therein seek

to establish a status, a right, or a particular fact. The petitioners therein (private

respondents herein) merely seek to establish the fact of death of their father and

subsequently to be duly recognized as among the heirs of the said deceased so that

they can validly exercise their right to participate in the settlement and liquidation of

the estate of the decedent consistent with the limited and special jurisdiction of the

probate court.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Caneba, Flores, Ranee, Acuesta and Masigla Law Firm for petitioners.

Ricardo E. Aragones for respondents.

[Vda. de Manalo vs. Court of Appeals, 349 SCRA 135, G.R. No. 129242 January

16, 2001]

DE LEON, JR., J.:

This is a petition for review on certiorari filed by petitioners Pilar S. Vda De Manalo,

et. Al., seeking to annul the Resolution 1 of the Court of Appeals 2 affirming the

Orders 3 of the Regional Trial Court and the Resolution 4which denied petitioner'

motion for reconsideration.

The antecedent facts 5 are as follows:

Troadio Manalo, a resident of 1996 Maria Clara Street, Sampaloc, Manila died

intestate on February 14, 1992. He was survived by his wife, Pilar S. Manalo, and his

eleven (11) children, namely: Purita M. Jayme, Antonio Manalo, Milagros M. Terre,

Belen M. Orillano, Isabelita Manalo, Rosalina M. Acuin, Romeo Manalo, Roberto

Manalo, Amalia Manalo, Orlando Manalo and Imelda Manalo, who are all of legal

age.1wphi1.nt

At the time of his death on February 14, 1992, Troadio Manalo left several real

properties located in Manila and in the province of Tarlac including a business under

the name and style Manalo's Machine Shop with offices at No. 19 Calavite Street, La

Loma, Quezon City and at NO. 45 General Tinio Street, Arty Subdivision,

Valenzuela, Metro Manila.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 10

On November 26, 1992, herein respondents, who are eight (8) of the surviving

children of the late Troadio Manalo, namely; Purita, Milagros, Belen Rocalina,

Romeo, Roberto, Amalia, and Imelda filed a petition 6 with the respondent Regional

Trial Court of Manila 7 of the judicial settlement of the estate of their late father,

Troadio Manalo, and for the appointment of their brother, Romeo Manalo, as

administrator thereof.

D. To deny the motion of the oppositors for the inhibition of this Presiding

Judge;

On December 15, 1992, the trial court issued an order setting the said petition for

hearing on February 11, 1993 and directing the publication of the order for three (3)

consecutive weeks in a newspaper of general circulation in Metro Manila, and

further directing service by registered mail of the said order upon the heirs named in

the petition at their respective addresses mentioned therein.

Herein petitioners filed a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court

with the Court of Appeals, docketed as CA-G.R. SP. No. 39851, after the trial court

in its Order 10 dated September 15, 1993. In their petition for improperly laid in SP.

PROC. No. 92-63626; (2) the trial court did not acquire jurisdiction over their

persons; (3) the share of the surviving spouse was included in the intestate

proceedings; (4) there was absence of earnest efforts toward compromise among

members of the same family; and (5) no certification of non-forum shopping was

attached to the petition.

On February 11, 1993, the date set for hearing of the petition, the trial court issued an

order 'declaring the whole world in default, except the government," and set the

reception of evidence of the petitioners therein on March 16, 1993. However, the trial

court upon motion of set this order of general default aside herein petitioners

(oppositors therein) namely: Pilar S. Vda. De Manalo, Antonio, Isabelita and Orlando

who were granted then (10) days within which to file their opposition to the petition.

E. To set the application of Romeo Manalo for appointment as regular

administrator in the intestate estate of the deceased Troadio Manalo for

hearing on September 9, 1993 at 2:00 o'clock in the afternoon.

Finding the contentions untenable, the Court of Appeals dismissed the petition for

certiorari in its Resolution11promulgated on September 30, 1996. On May 6, 1997 the

motion for reconsideration of the said resolution was likewise dismissed.12

Several pleadings were subsequently filed by herein petitioners, through counsel,

culminating in the filling of an Omnibus Motion 8 on July 23, 1993 seeking; (1) to

seat aside and reconsider the Order of the trial court dated July 9, 1993 which denied

the motion for additional extension of time file opposition; (2) to set for preliminary

hearing their affirmative defenses as grounds for dismissal of the case; (3) to declare

that the trial court did not acquire jurisdiction over the persons of the oppositors; and

(4) for the immediate inhibition of the presiding judge.

The only issue raised by herein petitioners in the instant petition for review is

whether or not the respondent Court of Appeals erred in upholding the questioned

orders of the respondent trial court which denied their motion for the outright

dismissal of the petition for judicial settlement of estate despite the failure of the

petitioners therein to aver that earnest efforts toward a compromise involving

members of the same family have been made prior to the filling of the petition but

that the same have failed.

On July 30, 1993, the trial court issued an order9 which resolved, thus:

Herein petitioners claim that the petition in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 is actually an

ordinary civil action involving members of the same family. They point out that it

contains certain averments, which, according to them, are indicative of its adversarial

nature, to wit:

A. To admit the so-called Opposition filed by counsel for the oppositors on

July 20, 1993, only for the purpose of considering the merits thereof;

B. To deny the prayer of the oppositors for a preliminary hearing of their

affirmative defenses as ground for the dismissal of this proceeding, said

affirmative defenses being irrelevant and immaterial to the purpose and

issue of the present proceeding;

C. To declare that this court has acquired jurisdiction over the persons of the

oppositors;

Par. 7. One of the surviving sons, ANTONIO MANALO, since the death of

his father, TROADIO MANALO, had not made any settlement, judicial or

extra-judicial of the properties of the deceased father TROADIO

MANALO.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 11

Par. 8. xxx the said surviving son continued to manage and control the

properties aforementioned, without proper accounting, to his own benefit

and advantage xxx.

X

the probate proceedings. In addition, the relief's prayed for in the said petition leave

no room for doubt as regard the intention of the petitioners therein (private

respondents herein) to seek judicial settlement of the estate of their deceased father,

Troadio Manalo, to wit;

X

PRAYER

Par. 12. That said ANTONIO MANALO is managing and controlling the

estate of the deceased TROADIO MANALO to his own advantage and to

the damage and prejudice of the herein petitioners and their co-heirs xxx.

X

Par. 14. For the protection of their rights and interests, petitioners were

compelled to bring this suit and were forced to litigate and incur expenses

and will continue to incur expenses of not less than, P250,000.00 and

engaged the services of herein counsel committing to pay P200,000.00 as

and attorney's fees plus honorarium of P2,500.00 per appearance in court

xxx.13

Consequently, according to herein petitioners, the same should be dismissed under

Rule 16, Section 1(j) of the Revised Rules of Court which provides that a motion to

dismiss a complaint may be filed on the ground that a condition precedent for filling

the claim has not been complied with, that is, that the petitioners therein failed to

aver in the petition in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626, that earnest efforts toward a

compromise have been made involving members of the same family prior to the

filling of the petition pursuant to Article 222 14 of the Civil Code of the Philippines.

The instant petition is not impressed with merit.

It is a fundamental rule that in the determination of the nature of an action or

proceeding, the averments15 and the character of the relief sought 16 in the complaint,

or petition, as in the case at bar, shall be controlling. A careful srutiny of the Petition

for Issuance of Letters of Administration, Settlement and Distribution of Estatein SP.

PROC. No. 92-63626 belies herein petitioners' claim that the same is in the nature of

an ordinary civil action. The said petition contains sufficient jurisdictional facts

required in a petition for the settlement of estate of a deceased person such as the fat

of death of the late Troadio Manalo on February 14, 1992, as well as his residence in

the City of Manila at the time of his said death. The fact of death of the decedent and

of his residence within he country are foundation facts upon which all the subsequent

proceedings in the administration of the estate rest. 17The petition is SP.PROC No. 9263626 also contains an enumeration of the names of his legal heirs including a

tentative list of the properties left by the deceased which are sought to be settled in

WHEREFORE, premises considered, it is respectfully prayed for of this Honorable

Court:

a. That after due hearing, letters of administration be issued to petitioner

ROMEO MANALO for the administration of the estate of the deceased

TROADIO MANALO upon the giving of a bond in such reasonable sum

that this Honorable Court may fix.

b. That after all the properties of the deceased TROADIO MANALO have

been inventoried and expenses and just debts, if any, have been paid and the

legal heirs of the deceased fully determined, that the said estate of

TROADIO MANALO be settled and distributed among the legal heirs all in

accordance with law.

c. That the litigation expenses of these proceedings in the amount of

P250,000.00 and attorney's fees in the amount of P300,000.00 plus

honorarium of P2,500.00 per appearance in court in the hearing and trial of

this case and costs of suit be taxed solely against ANTONIO MANALO. 18

Concededly, the petition in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 contains certain averments

which may be typical of an ordinary civil action. Herein petitioners, as oppositors

therein, took advantage of the said defect in the petition and filed their so-called

Opposition thereto which, as observed by the trial court, is actually an Answer

containing admissions and denials, special and affirmative defenses and compulsory

counterclaims for actual, moral and exemplary damages, plus attorney's fees and

costs 19 in an apparent effort to make out a case of an ordinary civil action and

ultimately seek its dismissal under Rule 16, Section 1(j) of the Rules of Court vis-vis, Article 222 of civil of the Civil Code.

It is our view that herein petitioners may not be allowed to defeat the purpose of the

essentially valid petition for the settlement of the estate of the late Troadio Manalo

by raising matters that as irrelevant and immaterial to the said petition. It must be

emphasized that the trial court, siting as a probate court, has limited and special

jurisdiction 20 and cannot hear and dispose of collateral matters and issues which may

be properly threshed out only in an ordinary civil action. In addition, the rule has

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 12

always been to the effect that the jurisdiction of a court, as well as the concomitant

nature of an action, is determined by the averments in the complaint and not by the

defenses contained in the answer. If it were otherwise, it would not be too difficult to

have a case either thrown out of court or its proceedings unduly delayed by simple

strategem.21 So it should be in the instant petition for settlement of estate.

Herein petitioners argue that even if the petition in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 were to

be considered as a special proceeding for the settlement of estate of a deceased

person, Rule 16, Section 1(j) of the Rules of Court vis--visArticle 222 of the Civil

Code of the Philippines would nevertheless apply as a ground for the dismissal of the

same by virtue of ule 1, Section 2 of the Rules of Court which provides that the 'rules

shall be liberally construed in order to promote their object and to assist the parties in

obtaining just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every action and

proceedings.' Petitioners contend that the term "proceeding" is so broad that it must

necessarily include special proceedings.

The argument is misplaced. Herein petitioners may not validly take refuge under the

provisions of Rule 1, Section 2, of the Rules of Court to justify the invocation of

Article 222 of the Civil Code of the Philippines for the dismissal of the petition for

settlement of the estate of the deceased Troadio Manalo inasmuch as the latter

provision is clear enough. To wit:

hate and passion in the family. It is know that lawsuit between close

relatives generates deeper bitterness than stranger.25

It must be emphasized that the oppositors (herein petitioners) are not being sued in

SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 for any cause of action as in fact no defendant was

imploded therein. The Petition for issuance of letters of Administration, Settlement

and Distribution of Estate in SP. PROC. No. 92-63626 is a special proceeding and, as

such, it is a remedy whereby the petitioners therein seek to establish a status, a right,

or a particular fact. 26 the petitioners therein (private respondents herein) merely seek

to establish the fat of death of their father and subsequently to be duly recognized as

among the heirs of the said deceased so that they can validly exercise their right to

participate in the settlement and liquidation of the estate of the decedent consistent

with the limited and special jurisdiction of the probate court.1wphi1.nt

WHEREFORE, the petition in the above-entitled case, is DENIED for lack of merit,

Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

Art. 222. No suit shall be filed or maintained between members of the same family

unless it should appear that earnest efforts toward a compromise have been made, but

that the same have failed, subject to the limitations in Article 2035(underscoring

supplied).22

The above-quoted provision of the law is applicable only to ordinary civil actions.

This is clear from the term 'suit' that it refers to an action by one person or persons

against another or other in a court of justice in which the plaintiff pursues the remedy

which the law affords him for the redress of an injury or the enforcement of a right,

whether at law or in equity. 23 A civil action is thus an action filed in a court of

justice, whereby a party sues another for the enforcement of a right, or the prevention

or redress of a wrong.24 Besides, an excerpt form the Report of the Code Commission

unmistakably reveals the intention of the Code Commission to make that legal

provision applicable only to civil actions which are essentially adversarial and

involve members of the same family, thus:

It is difficult to imagine a sadder and more tragic spectacle than a litigation

between members of the same family. It is necessary that every effort

should be made toward a compromise before litigation is allowed to breed

G.R. No. L-28394 November 26, 1970

PEDRO GAYON, plaintiff-appellant,

vs.

SILVESTRE GAYON and GENOVEVA DE GAYON, defendants-appellees.

German M. Lopez for plaintiff-appellant.

Pedro R. Davila for defendants-appellees.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 13

Civil Law; Succession; Acquisition of Ownership; Legitime; Widow's Interest.As

a widow, she is one of her deceased husband's compulsory heirs [Art. 887(3), Civil

Code] and has, accordingly, an interest in the property in question.

Same; Same; Suit against heirs.Inasmuch as succession takes place by operation of

law, "from the moment of the death of the decedent" (Arts. 774 and 777, Civil Code)

and "the inheritance includes all the property, rights and obligations of a person

which are not extinguished by his death," (Art. 776, Civil Code) it follows that if his

heirs were included as defendants, they would be sued, not as "representatives" of the

decedent, but as owners of an aliquot interest in the property in question, even if the

precise extent of their interest may still be undetermined and they have derived it

from the decedent. Hence, they may be sued without a previous declaration of

heirship, provided there is no pending special proceeding for the settlement of the

estate of the decedent.

Same; Same; Family Relations; Suit between members of the same family, defined.

It is noteworthy that the impediment arising from the provision of Art. 222 of the

Civil Code applies to suits "filed or maintained between members of the same

family." This phrase, "members of the same family," should, however, be construed

in the light of Article 217 of the same Code.

Same; Same; Same; Suit against sister-in-law, nephews and nieces.Inasmuch as a

sister-in-law, nephew or niece is not included in the enumeration contained in Article

217, Civil Code, which should be construed strictly, it being an exception to the

general rule, it follows that the same does not come within the purview of Art. 222,

and plaintiff's failure to seek a compromise before filing the complaint does not bar

the same.

APPEAL from an order of the Court of First Instance of Iloilo. Rovira, J.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

[Gayon vs. Gayon, 36 SCRA 104, No. L-28394 November 26, 1970]

CONCEPCION, C.J.:

Appeal, taken by plaintiff Pedro Gayon, from an order of the Court of First Instance

of Iloilo dismissing his complaint in Civil Case No. 7334 thereof.

The records show that on July 31, 1967, Pedro Gayon filed said complaint against

the spouses Silvestre Gayon and Genoveva de Gayon, alleging substantially that, on

October 1, 1952, said spouses executed a deed copy of which was attached to the

complaint, as Annex "A" whereby they sold to Pedro Gelera, for the sum of

P500.00, a parcel of unregistered land therein described, and located in the barrio of

Cabubugan, municipality of Guimbal, province of Iloilo, including the improvements

thereon, subject to redemption within five (5) years or not later than October 1, 1957;

that said right of redemption had not been exercised by Silvestre Gayon, Genoveva

de Gayon, or any of their heirs or successors, despite the expiration of the period

therefor; that said Pedro Gelera and his wife Estelita Damaso had, by virtue of a deed

of sale copy of which was attached to the complaint, as Annex "B" dated

March 21, 1961, sold the aforementioned land to plaintiff Pedro Gayon for the sum

of P614.00; that plaintiff had, since 1961, introduced thereon improvements worth

P1,000; that he had, moreover, fully paid the taxes on said property up to 1967; and

that Articles 1606 and 1616 of our Civil Code require a judicial decree for the

consolidation of the title in and to a land acquired through a conditional sale, and,

accordingly, praying that an order be issued in plaintiff's favor for the consolidation

of ownership in and to the aforementioned property.

In her answer to the complaint, Mrs. Gayon alleged that her husband, Silvestre

Gayon, died on January 6, 1954, long before the institution of this case; that Annex

"A" to the complaint is fictitious, for the signature thereon purporting to be her

signature is not hers; that neither she nor her deceased husband had ever executed

"any document of whatever nature in plaintiff's favor"; that the complaint is

malicious and had embarrassed her and her children; that the heirs of Silvestre

Gayon had to "employ the services of counsel for a fee of P500.00 and incurred

expenses of at least P200.00"; and that being a brother of the deceased Silvestre

Gayon, plaintiff "did not exert efforts for the amicable settlement of the case" before

filing his complaint. She prayed, therefore, that the same be dismissed and that

plaintiff be sentenced to pay damages.

Soon later, she filed a motion to dismiss, reproducing substantially the averments

made in her answer and stressing that, in view of the death of Silvestre Gayon, there

is a "necessity of amending the complaint to suit the genuine facts on record."

Presently, or on September 16, 1967, the lower court issued the order appealed from,

reading:

Considering the motion to dismiss and it appearing from Exhibit

"A" annexed to the complaint that Silvestre Gayon is the absolute

owner of the land in question, and considering the fact that

Silvestre Gayon is now dead and his wife Genoveva de Gayon has

nothing to do with the land subject of plaintiff's complaint, as

prayed for, this case is hereby dismissed, without pronouncement

as to costs.1

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 14

A reconsideration of this order having been denied, plaintiff interposed the present

appeal, which is well taken.

Said order is manifestly erroneous and must be set aside. To begin with, it is not true

that Mrs. Gayon "has nothing to do with the land subject of plaintiff's complaint." As

the widow of Silvestre Gayon, she is one of his compulsory heirs 2and has,

accordingly, an interest in the property in question. Moreover, her own motion to

dismiss indicated merely "a necessity of amending the complaint," to the end that the

other successors in interest of Silvestre Gayon, instead of the latter, be made parties

in this case. In her opposition to the aforesaid motion for reconsideration of the

plaintiff, Mrs. Gayon alleged, inter alia, that the "heirs cannot represent the dead

defendant, unless there is a declaration of heirship." Inasmuch, however, as

succession takes place, by operation of law, "from the moment of the death of the

decedent" 3and "(t)he inheritance includes all the property, rights and obligations of a

person which are not extinguished by his death," 4it follows that if his heirs were

included as defendants in this case, they would be sued, not as "representatives" of

the decedent, but as owners of an aliquot interest in the property in question, even if

the precise extent of their interest may still be undetermined and they have derived it

from the decent. Hence, they may be sued without a previous declaration of heirship,

provided there is no pending special proceeding for the settlement of the estate of the

decedent. 5

As regards plaintiff's failure to seek a compromise, as an alleged obstacle to the

present case, Art. 222 of our Civil Code provides:

No suit shall be filed or maintained between members of the same

family unless it should appear that earnest efforts toward a

compromise have been made, but that the same have failed, subject

to the limitations in article 2035.

It is noteworthy that the impediment arising from this provision applies to suits "filed

or maintained between members of the same family." This phrase, "members of the

same family," should, however, be construed in the light of Art. 217 of the same

Code, pursuant to which:

Family relations shall include those:

(1) Between husband and wife;

(2) Between parent and child;

(3) Among other ascendants and their descendants;

(4) Among brothers and sisters.

Mrs. Gayon is plaintiff's sister-in-law, whereas her children are his nephews and/or

nieces. Inasmuch as none of them is included in the enumeration contained in said

Art. 217 which should be construed strictly, it being an exception to the general

rule and Silvestre Gayon must necessarily be excluded as party in the case at bar,

it follows that the same does not come within the purview of Art. 222, and plaintiff's

failure to seek a compromise before filing the complaint does not bar the same.

WHEREFORE, the order appealed from is hereby set aside and the case remanded to

the lower court for the inclusion, as defendant or defendants therein, of the

administrator or executor of the estate of Silvestre Gayon, if any, in lieu of the

decedent, or, in the absence of such administrator or executor, of the heirs of the

deceased Silvestre Gayon, and for further proceedings, not inconsistent with this

decision, with the costs of this instance against defendant-appellee, Genoveva de

Gayon. It is so ordered.

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 15

G.R. No. 97898 August 11, 1997

FLORANTE F. MANACOP, petitioner,

vs.

COURT OF APPEALS and E & L MERCANTILE, INC., respondents.

Family Code; Family Home; A final and executory decision promulgated and a writ

of execution issued before the effectivity of the Family Code can be executed on a

house and lot constituted as a family home under the provisions of the said Code.

Petitioner contends that the trial court erred in holding that his residence was not

exempt from execution in view of his failure to show that the property involved has

been duly constituted as a family home in accordance with law. He asserts that the

Family Code and Modequillo require simply the occupancy of the property by the

petitioner, without need for its judicial or extrajudicial constitution as a family home.

Petitioner is only partly correct. True, under the Family Code which took effect on

August 3, 1988, the subject property became his family home under the simplified

process embodied in Article 153 of said Code. However, Modequillo explicitly ruled

that said provision of the Family Code does not have retroactive effect. In other

words, prior to August 3, 1988, the procedure mandated by the Civil Code had to be

followed for a family home to be constituted as such. There being absolutely no

proof that the subject property was judicially or extrajudicially constituted as a

family home, it follows that the laws protective mantle cannot be availed of by

petitioner. Since the debt involved herein was incurred and the assailed orders of the

trial court issued prior to August 3, 1988, the petitioner cannot be shielded by the

benevolent provisions of the Family Code.

Same; Same; Words and Phrases; The occupancy of the family home either by the

owner thereof or by any of its beneficiaries must be actual, and that which is

actual is something real, or actually existing, as opposed to something merely

possible, or to something which is presumptive or constructive.In view of the

foregoing discussion, there is no reason to address the other arguments of petitioner

other than to correct his misconception of the law. Petitioner contends that he should

be deemed residing in the family home because his stay in the United States is

merely temporary. He asserts that the person staying in the house is his overseer and

that whenever his wife visited this country, she stayed in the family home. This

contention lacks merit. The law explicitly provides that occupancy of the family

home either by the owner thereof or by any of its beneficiaries must be actual. That

which is actual is something real, or actually existing, as opposed to something

merely possible, or to something which is presumptive or constructive.

Same; Same; Same; Beneficiaries, Explained; Maids and overseers are not the

beneficiaries contemplated by Art. 154 of the Family Codeoccu pancy of a family

home by an overseer is insufficient compliance with the law.Actual occupancy,

however, need not be by the owner of the house specifically. Rather, the property

may be occupied by the beneficiaries enumerated by Article 154 of the Family

Code. Art. 154. The beneficiaries of a family home are: (1) The husband and wife,

or an unmarried person who is the head of the family; and (2) Their parents,

ascendants, descendants, brothers and sisters, whether the relationship be legitimate

or illegitimate, who are living in the family home and who depend upon the head of

the family for lead support. This enumeration may include the in-laws where the

family home is constituted jointly by the husband and wife. But the law definitely

excludes maids and overseers. They are not the beneficiaries contemplated by the

Code. Consequently, occupancy of a family home by an overseer like Carmencita V.

Abat in this case is insufficient compliance with the law.

PETITION for review on certiorari of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Jose F. Manacop for petitioner.

Cesar D. Turiano for private respondent.

[Manacop vs. Court of Appeals, 277 SCRA 57, G.R. No. 97898 August 11, 1997]

PANGANIBAN, J.:

May a writ of execution of a final and executory judgment issued before the

effectivity of the Family Code be executed on a house and lot constituted as a family

home under the provision of said Code?

State of the Case

This is the principal question posed by petitioner in assailing the Decision

of Respondent Court of Appeals 1in CA-G.R. SP No. 18906 promulgated on

February 21, 1990 and its Resolution promulgated on March 21, 1991,

affirming the orders issued by the trial court commanding the issuance of

various writs of execution to enforce the latter's decision in Civil Case No.

53271.

The Facts

PERSONS REVIEW ASSIGNMENT No. 11 Page 16

Petitioner Florante F. Manacop 2 and his wife Eulaceli purchased on March

10, 1972 a 446-square-meter residential lot with a bungalow, in

consideration of P75,000.00. 3 The property, located in Commonwealth

Village, Commonwealth Avenue, Quezon City, is covered by Transfer

Certificate of Title No. 174180.

On March 17, 1986, Private Respondent E & L Merchantile, Inc. filed a

complaint against petitioner and F.F. Manacop Construction Co., Inc. before

the Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Metro Manila to collect an indebtedness

of P3,359,218.45. Instead of filing an answer, petitioner and his company

entered into a compromise agreement with private respondent, the salient

portion of which provides:

c. That defendants will undertake to pay the amount of

P2,000,000.00 as and when their means permit, but expeditiously

as possible as their collectibles will be collected. (sic)

On April 20, 1986, the trial court rendered judgment approving the

aforementioned compromise agreement. It enjoined the parties to comply

with the agreement in good faith. On July 15, 1986, private respondent filed

a motion for execution which the lower court granted on September 23,

1986. However, execution of the judgment was delayed. Eventually, the

sheriff levied on several vehicles and other personal properties of petitioner.

In partial satisfaction of the judgment debt, these chattels were sold at

public auction for which certificates of sale were correspondingly issued by

the sheriff.

On August 1, 1989, petitioner and his company filed a motion to quash the

alias writs of execution and to stop the sheriff from continuing to enforce

them on the ground that the judgment was not yet executory. They alleged

that the compromise agreement had not yet matured as there was no

showing that they had the means to pay the indebtedness or that their

receivables had in fact been collected. They buttressed their motion with

supplements and other pleadings.

On August 11, 1989, private respondent opposed the motion on the

following grounds: (a) it was too late to question the September 23, 1986

Order considering that more than two years had elapsed; (b) the second alias

writ of execution had been partially implemented; and (c) petitioner and his

company were in bad faith in refusing to pay their indebtedness

notwithstanding that from February 1984 to January 5, 1989, they had

collected the total amount of P41,664,895.56. On September 21, 1989,

private respondent filed an opposition to petitioner and his company's

addendum to the motion to quash the writ of execution. It alleged that the

property covered by TCT No. 174180 could not be considered a family

home on the grounds that petitioner was already living abroad and that the

property,

having

been

acquired

in

1972,

should

have

been judicially constituted as a family home to exempt it from execution.

On September 26, 1989, the lower court denied the motion to quash the writ

of execution and the prayers in the subsequent pleadings filed by petitioner

and his company. Finding that petitioner and his company had not paid their

indebtedness even though they collected receivables amounting to

P57,224,319.75, the lower court held that the case had become final and

executory. It also ruled that petitioner's residence was not exempt from

execution as it was not duly constituted as a family home, pursuant to the

Civil Code.

Hence, petitioner and his company filed with the Court of Appeals a petition

for certiorari assailing the lower court's Orders of September 23,

1986 and September 26, 1989. On February 21, 1990, Respondent Court of