Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Political Economy of Foreign Investment in Latin America

Încărcat de

Bill LevenDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Political Economy of Foreign Investment in Latin America

Încărcat de

Bill LevenDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Political Economy of Foreign

Investment in Latin America

Dependency Revisited

by

Andy Higginbottom

Examination of foreign investment inflows, stock, and outgoing profit flows from Latin

America in the neoliberal period shows that the basic tenet of the dependency thesis still

holds: there is a huge and underreported transfer of surplus value out of the continent.

European capital has overtaken U.S. capital as a source of investment, and within the

Andean region there are two distinct groups of countries with regard to investment

regime: the Andean nations of the Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra

Amrica (Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela), which have succeeded in increasing the proportion of surplus profits retained in their national economies against that part captured

by international capital, and their non-ALBA neighbors. A new dialectic of domination

and dependency is at work, with the focus on contesting bilateral free-trade agreements

and investment treaties.

Un anlisis de la inversin extranjera, las acciones y el flujo de beneficios externos

producidos en Amrica Latina durante el perodo neoliberal muestra que an se mantiene

el principio bsico de la tesis de la dependencia: hay una enorme transferencia de plusvala

fuera del continente, una buena parte de la cual no se reporta. El capital europeo ha

superado al capital estadounidense como fuente de inversin y, dentro de la regin andina,

hay dos grupos de pases con distintas estrategias en relacin al rgimen de inversiones:

en el primero estn los miembros de la Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra

Amrica (Bolivia, Ecuador y Venezuela), que han logrado aumentar la proporcin de

excedentes retenidos en sus economas nacionales en relacin a la parte capturada por el

capital internacional; en el segundo, sus vecinos que no pertenecen a ALBA. Aqu se est

desarrollando una nueva dialctica de dominacin y dependencia centrada en la disputa

alrededor de acuerdos bilaterales de libre comercio y tratados de inversin.

Keywords: Foreign direct investment, Dependency, Europe, Regime of accumulation

At the turn of the millennium it was fitting to present Latin America as a

continent poised at the crossroads, trying to decide the direction it would take.

At issue was whether countries would accept, reject, or accommodate the

United States grand plan, the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA).

The agreement was defeated, but the strategic threat behind it has taken on

new forms. While the specific indecision of that historical moment has passed,

Andy Higginbottom is principal lecturer of international politics and human rights at Kingston

University in the UK. He is also secretary of the Colombia Solidarity Campaign. He thanks

Rosalind Bresnahan and Steve Ellner for their probing comments.

LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES, Issue 190, Vol. 40 No. 3, May 2013 184-206

DOI: 10.1177/0094582X13479304

2013 Latin American Perspectives

184

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 185

the rift that it fostered has continued to grow as each government determines

its development strategy.

The international economic context has for the past decade been set by the

prolonged boom in commodity prices that fuels expanding production in

China and India. Global competition has shaped sectors in Latin American

countries depending on whether they are competing with or supplying materials for the new production platforms in Asia. Large parts of South America

have experienced an upsurge in export-oriented production, with the primary

sectors attracting large-scale foreign capital investments and, in Brazil, domestic capital as well. This has meant the return, especially in the smaller, less

industrialized countries, of a dependent extractive economy based on the

export of nonrenewable natural resources. The question is not simply how

Latin America has been reincorporated into the global economy but how global

capital has reinserted itself into Latin America, exploiting labor and land, in the

current conditions. Out-transfers of value are leaving the popular classes just

as impoverished as before, with the additional legacies of dispossession and

environmental destruction, except where national governments have taken

programmatic action to break the cycle of capitalist underdevelopment.

The Andean countries are a case in point. The political dynamics of the subregion have been marked by a polarization between Chile, Peru, and Colombia,

on the one hand, and Venezuela, Bolivia, and, more equivocally, Ecuador, on

the other. One point of difference between the groupings concerns the political

economy of foreign investment. This article uses quantitative data as evidence

of a distinction between the former group, which is openly collusive with foreign capital, and the latter, which seeks to regulate and contain the penetration

of global capital. Two political-economic models are rubbing against each other

in permanent friction, giving rise to a new level of indeterminacy and, as with

a geological fault line, a constantly threatening tension.

The 2008 financial crisis in the United States and Europe and ensuing austerity offensives amplify the resonance of any popular gains in Latin America,

adding to the sense that there are more definitive battles to comeevents that

will decide whether history repeats itself with yet another catastrophic defeat

for the left or whether it will be possible to consolidate a completely distinct

political economy that opens new possibilities beyond capitalism.

Modernization vs. Dependency Revisited

There is a commonality between the current cycle of capitalist development

and previous cycles. From the multidimensional and often confused discussion

of globalization themes, a contest has emerged that revisits the debates between

the modernization and dependency paradigms of the 1960s and 1970s. The

modernization school was represented by John F. Kennedys presidential

adviser W. W. Rostow (1990 [1960]), who argued that developing countries

would have to modernize their traditional social forms, behaviors, and institutions, following the same road as the rich, industrialized countries of the North,

as a precondition for the takeoff of their economies. The dependency school

emerged in clear opposition to this view, holding that exploitative relations

186LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

exist between the rich countries at the center of the world system and the poor

countries in the periphery. As a leading dependency writer put it, underdevelopment is a consequence and part of the process of the world expansion of

capitalism, with a transfer of resources from the most backward and dependent sectors to the most advanced and dominant ones (Santos, 1970: 231).

Modernization is the ideological self-expression of foreign capital that sees

itself as the positive subject bringing progress. The return of the modernization

paradigm and its fight for hegemony is theorized in recent work by writers of

the center-right (Edwards, 2009; 2010; Fukuyama, 2008; Reid, 2007). Presenting

itself as the challenger to a radical and romantic but essentially outmoded populist orthodoxy, the right has thrown down the gauntlet. According to Edwards

(2009: 31), The idea that Latin Americas long-term decline is the result of a

vast Northern, capitalistic, and Anglo Saxon conspiracy, simply, doesnt hold

any water. The causes of the regions mediocre economic performance have to

be looked for inside of Latin America. Michael Reid adds, Latin America has

moved on. . . . It is no longer the Latin America of Galeano, brilliant propagandist though he is, for a particular vision of history.1 The modernizers problematization of underdevelopment focuses on bad governance or, as Edwards

puts it, poor policies and weak institutions. It follows that, to succeed, Latin

American countries should adopt good governance and strong policies

and reform their institutions. Governments will deserve these positive adjectives only insofar as they open their markets and encourage foreign trade and

investment (Fukuyama, 2008: 282). Thus, although the role of foreign capital is

but one point in a development strategy, it is the pivot around which the entire

debate revolves.

The dependency paradigm generated a vast literature (see Chilcote, 2003).

In his classic article, Theotnio dos Santos (1970: 231) says that dependency is

a situation in which the economy of certain countries is conditioned by the

development and expansion of another economy to which the former is subjected. There was within the dependency paradigm a wide-ranging debate as

to the causes and mechanisms of the dependent condition. The Marxist wing

sought to ground dependency in a class analysis of exploitation, leading to a

reformulation of the concept even at its most general level. Thus, Enrique

Dussel (2001: 205) emphasizes that dependency is an international social relation and identifies the essence of the concept as the transfer of surplus value

out of the dependent region. According to dependency theory, the empirical

issue of value transfer is a crucial demarcation. Value transfer is an area in

which apparently simple quantitative differences can represent fundamentally

important categorical differences. The dependency school argues that systemic

value extraction generates underdevelopment or, at best, conditions a dependent development. Foreign investment specifically is reliant on a bipolar relation; investments that flow in do so only on the condition that profits are made

and flow back to the investing party. Rather than deny this, modernizers are

content to leave the issue of profit flows in the background.

The modernizers bluster is especially marked when it comes to the role of

foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI is conventionally defined as ownership by

a foreign party of 10 percent or more of an enterprise, enough to give it a lasting interest (OECD, 2001). Modernizers deem FDI essential for development.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 187

Railing against what they consider to be the harmful residual influence of leftwing dependency thought, they claim that the facts are on their side. Reid

(2007: 39) portrays the dependency school as a theory in search of facts and

argues that dependency theorists employed ad hoc reasoning, such as the

notion that foreign investment decapitalized Latin America because the value

of repatriated profits over time might exceed the value of the original investment. This confused a stock and a flow. He is mistaken: dependency theory

does not claim that foreign investment has decapitalized Latin America.

Rather, it claims that foreign investment has exploited Latin Americathat

predatory capitalism has meant that a significant portion of the value produced

in the region is transferred out of it as profit. In short, dependency theory does

not confuse FDI stocks with FDI flows. Reids own error is, however, more

basic: he fails to distinguish qualitatively between FDI flowing in as capital

seeking profit and the realized dividends and other profits flowing out.

Ignoring outgoing profit flows is a crucial feature of the rights version. Reid

sees multinationals as positive agents, albeit with a few flaws; he denies the

extractive and exploitative character of the investment relationship. What he

ignores is the raison dtre for these investments: that they generate a return on

the capital invested. In fact, this is only partially measured by the profit revenues flowing out of Latin America.

This article argues for a restatement of the dependency thesis appropriately

adapted to the specific conditions of underdevelopment in the neoliberal

period. It disputes the modernizers central thesis that foreign investment is in

and of itself beneficial. A fuller challenge would require an evaluation of the

social and environmental effects of foreign investment that is beyond the scope

of one article. Here I concentrate on establishing the quantitative aspects of

financial flows as a point of departure in a wider debate.

The article actualizes Dussels general concept of dependency as value transfer. It asks how big the profits from FDI are and where they are going. It then

focuses on the sharp differentiation in the Andean region between two types of

investment regime. The argument rests on interpreting the economic indicators

on international transfers and falls into three parts. First, there has been a truly

dramatic upsurge in European Union (EU) direct investment in the region;

European capital has become a major beneficiary of value transfers out of Latin

America. Secondly, the splitting of the Andean countries into two camps is

demonstrable in the pattern of investment flows and especially of repatriated

profit flows. Thirdly, these measures are the leading edge of a free-trade

architecture designed to consolidate and deepen neoliberalism.

On the Particularity of Neoliberalism as a Phase

Adopting the insights of the dependency thesis does not entail assuming

that nothing has changed in the region. Indeed, the neoliberal project over the

past two decades has clearly been to open up new fields for capital accumulation in Latin America, especially through the programmatic commitment to

privatization. Echoing Harrisons (2010) description of the neoliberal project in

Africa as a form of social engineering, I suggest that neoliberalism in Latin

188LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

America tends toward political re-engineering, a common project of an ensemble of right-wing forces seeking to establish stable state regimes that will be

conducive to profitable capital accumulation over the next generation. These

new regimes of capital accumulation are not at all laissez-faire; if anything,

they tend toward a strand of neoconservatism in which the government goes

on the offensive against any opposition.

The project is quite traditional in its economics, entailing the subordination

of all policy objectives to investment-led, export-oriented growth. Its innovative elements are the transnational coordination of specific political mechanisms required by the new regime of accumulation in the form of free-trade

and investment agreements backed up by national and supranational institutions and intense ideological framing of the project that is intolerant of social

sectors that are not in line with it. With the more democratically representative

branches of the liberal state subordinated to the executive, sectors are marked

as illegitimate political actors and their political expression delegitimized, isolated, and criminalized while multinationals are guaranteed privileged access

and secure and high profits. Free-trade and investment agreements from the

United States and, increasingly, the EU are crucial mechanisms in the new

regime of accumulation (see Latimer, 2012).

The FTAA was thwarted by a combination of popular mobilization and progressive government action that reached its height in 2003 and 2004. Despite

President Bushs evident discomfort at the loss to U.S. prestige, his policy team

immediately moved to a plan B strategy of signing bilateral agreements with

friendly governments in the region. Building on the basis of the North American

Free Trade Agreement (the economic bloc between the United States, Mexico,

and Canada that has been in force since 1994), the United States has driven its

new bilateral strategy hard, implementing an agreement with Chile in 2004 and

then, with far more evident opposition, with five countries in Central America

and the Dominican Republic in 2006. Today, free-trade agreements and bilateral

investment treaties play a role analogous to the structural adjustment programs

of the 1980s or, in the case of Africa, the Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiative, which sought to lock in neoliberal fundamentals (Harrison, 2010: 43).

Choosing and Reading The Economic Indicators

At first sight the aggregate economic indicators suggest that Latin America

has done well in the new millennium, with aggregate growth of the gross

domestic product (GDP) averaging around 4 percent from 2002 to 2011 despite

the dip in 2009 (World Bank, 2012). The growth has been mostly led by exports

in primary and raw materials fueled by burgeoning demand from China and

by remittances from emigrants. As Prez Caldentey and Vernengo (2008: 1)

write, Latin America now exports commodities and people. They show that

oil-exporting countries have seen rising prices (as have mineral exporters)

while the textile-exporting countries of Central America have seen declining

ones. Overall, there has been a return to the orthodox model of export-oriented

growth. But does this constitute development? In order to understand the

debate about development and growth, we need to reexamine some of the

standard indicators.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 189

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC),

the UN development agency, provides data based on returns from national

governments. ECLAC analysts draw attention to the dependency concept of

net resource transfers defined as net capital inflows less net interest and

other investment income payments abroad (Brcena and Titelman, 2009: 9).

Notoriously, because of its onerous debt repayments, Latin America suffered

hugely negative net resource transfers in the 1980s; it paid out (many times

over) against its debt liabilities amounts of money far higher than any incoming

investment. By contrast, the neoliberal investment boom of the early 1990s

meant a positive net resource transfer, with much more capital flowing in

than going out (ECLAC, 2009: 161). From the early 2000s there is once again a

net transfer out of the region, with repatriated profits considerably exceeding

new investment; the net transfer of resources turned negative in 2002 and has

averaged US$ billion 72 annually for the period 20022008(Brcena and

Titelman, 2009: 9).

Net resource transfer is a blunt instrument that needs to be disaggregated to

grasp the underlying movements. We need to interrogate the data in more

detail to discover where the transfers are coming from and where are they

going. The sources used are ECLAC, the UN Conference on Trade and

Development (UNCTAD), the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA),

and the EUs Eurostat service. They are all compiled in terms of the IMF standard set of definitions for national accounts (IMF, 1993). Because the data from

the BEA and Eurostat show considerable change from the first year to the second year of reporting, using data from the second year avoids the worst fluctuations. This means, however, that data are included only up to 2010, even

though in 2011 there was a significant increase in FDI flows into Latin America

and the Caribbean, estimated at 27 percent (UNCTAD, 2012a: 3).

In my computations of the source data to make the information more digestible, discrepancies or errors of interpretation may have been introduced with

regard to the originating countries and destination countries included, the

monetary unit of the indicators, and the definition of the indicator. The originating countries included are limited to the United States and the EU countries,

which between them source about three-quarters of the FDI in the period under

consideration. This is because the United States and the EU provide data indicating the rate of return on their investments. A complete analysis would need

to interrogate the national accounts of all originating countries. For the destination countries there is a major transparency issue. Flows through Caribbean

offshore financial centers (Anguilla, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the Virgin

Islands, and, arguably, Panama), where the identity of the originating and destination countries is kept opaque, have become huge since around 2005. For

example, some 27 percent of nonpetroleum foreign investment in Colombia

from 2006 to 2010 entered via the Antilles and Panama, but their ultimate origin

is not recorded (ProExport Colombia, 2012). Woodward (2001: 25) observes

that the growing incidence of offshore banking contributes to the apparent

statelessness of corporations. Corporations using offshore centers are, however, not so much stateless as tax-averse (Shaxson, 2011). This phenomenon

accelerated in the first decade of the twenty-first century. By 2008, U.S. flows

into Bermuda (US$7.8 billion) and the UKs Caribbean islands (US$25.9 billion)

190LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

were far greater than U.S. investment flows into the whole of Latin America

combined (US$19.9 billion) (BEA, 2012a). At the same time there has been a

change in the form of the investment vehicle, with investments made through

holding companies rising from 9 percent of outward investments in 1982 to 36

percent in 2008 (Ibarra and Koncz, 2009: 25). The Caribbean islands are for the

most part excluded from the aggregate data presented here, but the Bermuda

triangle money flows are now so enormous that the conclusions of any analysis that cannot identify ultimate sources and destinations are no more than

indicative.

There are differences in the countries included in the regional aggregations.

The EU and U.S. statistical services report Guyana and Surinam as part of

South America. ECLAC reports Guyana and Surinam as part of the Caribbean

and consequently does not include them in its aggregate figures for Latin

America. Guyane (French Guyana) does not appear in the data. ECLAC figures

report Haiti and Cuba separately, whereas the U.S. figures do not. The EU

includes Haiti as part of the Caribbean and Cuba as part of Latin America, and

so on. At the same time, the EU has grown in the period under consideration

from 15 to 27 affiliated states. EU figures are for all of the countries included in

the EU in any given year. Important though these differences are politically, it

is estimated that they cause only minor discrepancies in the data and certainly

much less than the offshoring of investment flows.

The monetary unit of the indicator is in most cases U.S. dollars. The EUs

statistics are in euros and are converted here into U.S. dollars at an exchange

rate appropriate to the specific itemat the end of the year for investment

stocks and an estimated average over the year for flows. The convention followed here is that a billion is a thousand million.

The definitions of the indicators are conceptually grounded in free-market

ideology. This does not invalidate their use, but critical qualifications are made

in the following presentation.

U.S. and EU Investments: Flows in, Stocks and Profits out

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the EU was the biggest source

of FDI to Latin America and the Caribbean, with about 40 percent of the total.

The United States and Canada invested 28 percent, and there was a small but

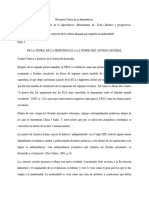

increasing share from Oceania and Asia (Table 1). Starting with investment

flows into Latin America, from 1997 to 2010 U.S.-based and EU-based multinationals directly invested between them a total of US$588.6 billion (Figure 1).

The overall pattern is an investment boom in the late 1990s, collapse of investments in the early 2000s (with a net disinvestment of U.S. capital from South

America in 2002) and a buildup again to 2007, a wobble as the financial crisis

began to hit at the end of 2008, and finally the beginnings of recovery.

It is clear that the EU overtook the United States as the main origin of FDI in

Latin America during the period. Starting from similar inward investment

flows in 1997, the investment flows from EU-based multinationals were greater

than flows from the United States each year. Over the five years 19982002

EU-based multinationals invested far more heavily. Within the EU, Spain

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 191

Table 1

Origins of Foreign Direct Investment (Percentages) in

Latin America and the Caribbean, 20002010

2000-2005

Latin

America

Brazil

Mexico

2006-2010

Latin

Latin

America

U.S.

America

U.S. and

and

Asia and

and

and

Asia and

Canada EU Caribbean Oceania Other Total Canada EU Caribbean Oceania Other Total

37.8

22.2

58.9

43.2

53.9

33.7

5.3

3.9

1.2

2.6

4.7

2.0

11.1 100.0

15.4 100.0

4.2 100.0

28.2

14.4

49.4

40.0

44.6

43.3

8.5

5.3

1.4

6.2

13.6

0.9

17.1 100.0

22.2 100.0

5.0 100.0

Source: ECLAC (2012a: 64).

Figure 1. FDI Flows into Latin America: U.S. vs. EU Origin, 19972010 (BEA, 2012a; Eurostat,

2012; and authors computation)

emerged as a major source of FDI to Latin America, surpassing the United

States in 1999 and 2000. Spanish investments declined over the next five years

but nonetheless still run at about a third of all EU investment. The reduced

inflow of FDI from the EU in 2008 is partly due to the behavior of what the

statisticians call Special Purpose Entities (SPEs). SPEs are often empty shells

or holding companies (Eurostat, 2010) that are not reported in EU national

data. According to Eurostat there was a large amount of disinvestment by

SPEs, mainly from the Netherlands, which is not explicitly shown in the tables

but in fact reduces the EU total (European Statistical Data Support, personal

communication, May 17, 2010). In other words, opaque investment flows

through financial centers operate increasingly inside the EU itself as well as

through physically offshore locations, and this presents a statistical challenge

(ECLAC, 2012a: 67).

192LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

Figure 2. FDI Stock (Investment Position) in Latin America: U.S. vs. EU, 19972010 (BEA,

2012b; Eurostat, 2012; and authors computation)

The year-on-year annual investment flows aggregate into assets held in a

country, becoming FDI stocks, with appropriate adjustments for capital gains,

retained profits, and other factors. FDI stock is also known as the foreign

investment position when viewed from the perspective of the source country.

The combined investment position of the United States and the EU in Latin

America, calculated on a historical cost basis, more than tripled, from US$191.8

billion to US$756.2 billion, between 1997 and 2010. Whereas U.S.-owned FDI

stocks in Latin America doubled in this period, EU-owned stocks increased

sixfold.

The investment surge from EU countries in the late 1990s meant that by the

turn of the millennium the EUs position in the region overtook that of the

United States and has continued to climb. At the beginning of the period U.S.based multinationals held two-thirds more assets than EU-based multinationals; by 2010 EU-based multinationals had nearly double the Latin American

direct investment stock of their U.S. counterparts (Figure 2). According to its

national accounts, Spains investment position in Latin America at the end of

2010 stood at stock assets valued at 125.1 billion euros (US$215.3 billion), making Spanish-based multinationals owners of 42 percent of all EU stock in Latin

America (Banco de Espaa, 2012: 140). The Netherlands is another significant

EU source of FDI; between 2005 and 2010 its investments in Argentina, Brazil,

and Mexico totaled US$51 billion (ECLAC, 2012a: 6465).

The crucial indicator ignored by Reid in his polemic against dependency

theory is the flow of investment income out of Latin America. The headline

figure is that U.S.-based and EU-based multinationals extracted a total of

US$477.6 billion in direct investment income out of Latin America between

1997 and 2010. For the period as a whole, U.S. investment income, at

US$250.8 billion, exceeds that of its EU counterparts, with US$226.8 billion.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 193

Figure 3. FDI Income from Latin America: U.S. vs. EU Destination, 19972010 (BEA, 2012c;

Eurostat, 2012; and authors computation)

Here again, however, the rise of EU-based multinationals is marked, starting

from only a third of U.S. investment income in 1997, when the EUs heavy

investments of the late 1990s began to generate revenue streams back to their

owners, and ending with profits similar to those of U.S. corporations from 2005

on (Figure 3).

The rule-of-thumb calculation conventionally used for the aggregate rate of

return on FDI is to divide the repatriated profits in one year by the FDI stock at

the end of the previous year, expressed as a percentage. The combined U.S. and

EU FDI stock in Latin America at the end of 2009 of US$661.8 billion generated

profit revenue of US$66.7 billion in 2010, an apparent overall rate of return of

10.1 percent on capital invested. It is striking that U.S. profits drawn out of

Latin America have stayed on a par with EU profits despite the relative diminution of U.S. investment stock.

The profit generated by a subsidiary includes the earnings reinvested in it as

well as the dividends that are repatriated to the foreign investor. Among Latin

American countries, only Brazil does not keep track of this figure (ECLAC,

2012b: 67). The proportion of reinvested earnings has grown considerably in

recent years, representing 45 percent of FDI flows to South American countries

other than Brazil in 20032011 (UNCTAD, 2012a: 53). To the degree that reinvested earnings have been growing, there is a diminishing proportion of

incoming FDI that is actually new investment. The reinvested earnings of U.S.

corporations in Latin America were 89.4 percent of all U.S. FDI from 2003 to

2010 (BEA, 2012d). A consequence of the reinvestment has been the pronounced

accumulation of foreign assets inside Latin America, building a permanent economic presence as a claim on future profits and political pressure that is accommodated to different degrees from one country to another.

194LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

Table 2

FDI Intensity (Incoming FDI Stocks as a Percentage

of GDP) by Latin American Country, 19902010

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Ecuador

Paraguay

Peru

Uruguay

Venezuela

South America

Mexico

1990

2000

2007

2008

2009

2010

5.5

21.1

8.5

48.1

7.3

14.5

8.5

4.5

8.0

8.2

9.6

8.5

23.8

61.8

19.0

60.8

11.9

39.8

18.7

20.7

10.4

30.3

23.4

16.7

25.7

41.8

23.2

60.7

27.2

23.2

18.5

25.0

26.2

18.6

26.2

25.3

23.5

36.0

17.8

58.2

27.7

20.7

14.2

25.0

25.7

14.1

21.6

27.3

25.9

37.0

25.2

79.5

32.0

22.4

18.7

26.5

40.0

12.6

27.7

31.6

23.6

35.0

32.3

76.0

28.7

20.1

17.4

27.3

36.8

10.3

30.8

32.0

Source: UNCTAD (2009; 2012b).

Investment Profiles of Latin American Countries

Next we look at the figures from the Latin America side of the investment

relation and ask where in Latin America the burgeoning FDI profits have come

from. To explore this question I introduce another standard indicator, FDI

intensity, which shows for each country the ratio of incoming FDI stock to

GDP and is conventionally taken as an indicator of how open an economy is

(Eurostat, 2010). Taken on its own this indicator is subject to various qualifications, especially concerning the use of GDP as a measure of value added in

production (Smith, 2010). Furthermore, open is of course an ideologically

weighted term suggesting positivity against the negative of closed. The differential incidence of the neoliberal model is well illustrated by a summary of

stocks of incoming FDI compared with GDP in different Latin American countries from 1990 to 2010 (Table 2). The overall pattern in the 1990s is of a rapid

opening up of South America to foreign investments; the regional ratio of FDI

stock to GDP increased by two and a half times, from 9.6 percent to 23.4 percent, in just 10 years. Chile stands out; by 1990 the Pinochet regime had invited

FDI penetration that was already an order of magnitude higher than its neighbors. The dictatorship in Bolivia also had atypically high FDI stock in proportion to GDP. Although in 2000 the most FDI-penetrated economies were still

Chile and Bolivia, during the 1990s the sharpest relative increases in FDI stock

were in Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay. Of the two largest Latin

American economies, that of Brazil has throughout been typical of the trend,

and while Mexico had lower than the average FDI intensity in the 1990s, it has

since 2000 continued to accumulate FDI liabilities at a greater rate than its GDP.

Whereas Chile has maintained its same high degree of FDI penetration over

the past decade, Bolivia has reduced its dependence on FDI, although it is still

at a high level. Venezuela markedly and, to a lesser degree, Ecuador have since

2000 reduced their FDI stock compared with GDP. By contrast, Colombia and

Uruguay, two countries that experienced slight increases in FDI stock in the

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 195

Table 3

Annual Average FDI Inflows to South America

(US$million) by Country, 19902000 and 20052010

19902000

20052010

US$m

% of Total

US$m

% of Total

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Ecuador

Peru

Paraguay

Uruguay

Venezuela

Other South America

South America

7,141

452

12,000

3,393

1,864

494

1,506

135

130

2,375

35

29,525

24.2

1.5

40.6

11.5

6.3

1.7

5.1

0.5

0.4

8.0

0.1

100.0

6,226

320

31,320

11,656

8,408

408

5,228

227

1,621

-179

372

65,607

9.5

0.5

47.7

17.8

12.8

0.6

8.0

0.3

2.5

-0.3

0.6

100.0

Source: UNCTAD (2010; 2012a) and authors computation.

1990s, have since 2000 rapidly opened up their economies to investment.

During the 2000s the greatest contrasts in movement of FDI stock relative to

GDP are found in the Andean subregion, with Bolivia, Venezuela, and Ecuador,

which reduced their FDI stock relative to their annual GDP, contrasting with

Peru and especially Colombia, which increased it from under 12 percent to 29

percent of GDP in 10 years. If Chile was the forerunner of the neoliberal model,

Colombia and Peru have since pushed hard in the same direction.

The governments of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela carried out limited

nationalizations in 2006 and 2007 and have increased their regulation of foreign

investment over the past decade (Rebossio, 2012; Tsolakis, 2011). In Bolivia these

measures were in direct response to the popular water wars and gas war that

brought Evo Morales to government. In Venezuela, Hugo Chvez has regained

control of the hydrocarbon sector from the domination of foreign capital. The

state oil corporation Petrleos de Venezuela acts as a vehicle for government

redistribution policy and is expected to enter into joint ventures with many different international partners (Stanley, 2008; Wallis and Paranga, 2012). The

degree to which Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela have been able to break from

the extractivist model and what this means for the project of twenty-firstcentury socialism are topics that need careful analysis (see Ellner in this issue).

What is clear is that they have sought less one-sided terms of engagement with

foreign investors. They have all withdrawn from the World Banks International

Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes. Evidence that foreign investors continue to see them as the least attractive destinations comes from Spanish

corporations, which cite political instability and juridical insecurity as the two

main reasons for not investing (IE Business School, 2012: 23); Chile, Colombia,

Peru, and Brazil are the main investment targets for these corporations (13).

The picture of divergent trends is corroborated by analysis of incoming FDI

flows by host country, comparing the annual average for the 1990s with the

annual average for 20052010 (Table 3). Argentina was a major target for FDI

196LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

investment in the 1990s, attracting 24.2 percent of all FDI coming into South

America. The big gainers in attracting FDI in the 2000 decade compared with

the 1990s were Chile, Peru, Uruguay, and Colombia. In 20052010 Chile took

17.8 percent and Colombia took 12.8 percent of all of South Americas FDI. By

contrast, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuelas incoming FDI declined in absolute

terms, and their aggregate relative share fell from 11.4 percent to just 0.8 percent of all FDI coming into South America. Again, these figures indicate the

existence of two distinct political-economic regimes for FDI in the Andean

subregion.

Brazil, the biggest country and economy in South America, increased its

incoming FDI from US$12 billion a year to over US$31 billion a year in this

period, and its share of all South Americas incoming FDI rose from 40.6 percent to 47.7 percent. While in Brazil too the export sector has been the main

driver of economic growth, in many cases, especially in food extraction and

minerals, national capital has also benefited and been able to accumulate rapidly. This is the basis of Brazils strong move to form national champions,

with the result that since 2003 its outgoing investments have increased rapidly

and account for some 67 percent of the outgoing direct investment from all

Latin American countries from 2000 to 2010. Nonetheless, FDI flows into Brazil

were four times the outgoing direct investments over this same period (ECLAC,

2012b). Analyzing this complex combination prompts a return to the theses of

superexploitation and subimperialism first developed by Ruy Mauro Marini.

Of all the dependency theoreticians, it was Marini who mostly firmly placed

the social relations of production and the experience of the working class at the

center of analysis. He demonstrated that under the conditions of mid-nineteenth-century free trade with Britain, the mechanism of unequal exchange

operated as a profit squeeze on Brazilian export capitalists, who responded by

increasing the exploitation of their workforces, which were exhausted, poorly

paid, and barely able to subsist (Marini, 1973; Sotelo Valencia, 2005). Marinis

innovative yet fundamentally materialist thesis was critiqued by Cardoso and

Serra, who preferred a more contingent explanation based on political institutions. Their exchange remains a vital entry point into serious study of underdevelopment as a singularity of the capitalist social relation (Kay, 1989).

Along with FDI stocks and flows, as we have seen, the third crucial element

is the repatriated profits that accrue from foreign investments. Modernization

theorists like Reid overlook this indicator completely. Moreover, the reformoriented, institutionalized opposition to neoliberalism known as neostructuralism (for a review of this literature see Kirby, 2009) has also

underplayed the significance of repatriated profits. The relevant summary was

not published in ECLACs annual reports until 2012, although it is available in

the detailed national figures. The nomenclature used here follows the standard

IMF categories in the balance of payments that national accounts are expected

to adhere to. The IMF divides income headings between compensation for

employees and investment income and subdivides investment income between

receipts and payments of income from direct investments, income from portfolio investments, and other investment income (including loan interest payments). These items appear under the Income heading of the current account

but should be more readily identified for what they really are: property incomerelated profit transfers.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 197

Figure 4. Andean Countries Income Balances, 19972010: Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela

(BEV) vs. Chile, Colombia, and Peru (CCP) (ECLAC, 2012b)

The outflow of investment income from Latin American countries in 2010

alone totaled US$139.4 billion; with an inflowing investment income of US$26.0

billion. The outgoing profit flow amounted to US$77.7 billion in direct investment profits, US$18.6 in portfolio investment profits, and US$30.4 billion profits from company loans and other investments. When these are offset against

incoming profits for Latin American multinationals investing abroad and

employees compensation transferred to Latin American countries, there still

remains a negative balance on income of US$113.4 billion (ECLAC, 2012b).

The net outflow of profits, or negative income balance, constitutes nearly

3 percent of the Latin Americas aggregate annual GDP and is firm evidence

that the dependency school contention of a transfer of value out of the continent remains valid. This figure understates the full extent of this value transfer;

a full estimate would need to include other value-transfer mechanisms such as

international prices below commodity values, loan interest payments, and the

emigration of socially prepared labor power.

The concept of the net outflow of profits helps to highlight differences in

political-economic regime in the Andean region. Comparing the aggregate

income balances between 1997 and 2010 of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela

with those of Chile, Colombia, and Peru (Figure 4), we observe that for the first

five years of the period outflowing revenues moved roughly in step. A point of

sharp divergence came around 2003, when the net outflow of revenues from

Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela began to decline; outflowing revenues from

Bolivia and Ecuador stayed fairly stable from 2003 to 2010, and the groups

aggregate figures reflect primarily the sea change in Venezuelas policy after

the 2003 failed coup attempt. These figures are crucial; they demonstrate that

Venezuela is not acting like a normally dependent Third World country, a

198LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

source of net profits for foreign investors. We see outlined in these figures the

effect of the Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra Amrica

(Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our AmericaALBA) in diminishing

dependency. By contrast, the returns to foreign direct investors in Chile,

Colombia, and Peru all accelerated sharply from 2002 on. In 2010 alone

Colombia returned US$12.1 billion in repatriated investment income, Chile

US$15.4 billion, and Peru US$10.0 billion (ECLAC, 2012b). The extractiveindustry investors in these three countries have reaped the profits of the commodities price boom that began to slow down only in 2008.

The Politics of European Capitals Expansionist Agenda

Por qu no te callas! The outburst of Juan Carlos, King of Spain, directed

at President Hugo Chvez during the Ibero-American Summit in Chile in

November 2007 has passed into legend. Chvez had been joined by Nicaraguan

president Daniel Ortega in a concerted rebuke of Spain. Juan Carloss exclamation became a hit with the populist right. What was it that drove the Venezuelan

and Nicaraguan leaders to break so sharply with the courtesies of international

protocol?

Chvez and Ortega had two good reasons to complain, and together they

illuminate the growing importance of European capital and its associated

forceful right-wing project in Latin America. Chvez brought into full view the

constant agitation by the supposedly democratic, constitutional Spanish elite

against progressive Latin American governments. Earlier on in the summit,

Jos Luis Zapatero had demanded respect for his predecessor, Jos Mara

Aznar, the leader of the conservative Partido Popular who had governed Spain

from 1996 to 2004. Noting that Aznar had openly backed the attempted coup

against his government in April 2002, Chvez insisted on registering his opinion of Aznar as a fascist, with some justification. Aznar spent a good deal of

2007 on tour in Latin America accusing Chvez of being an adversary of liberty. During the very week of the summit, Aznar was visiting Colombia to

preach his gospel of overthrow; presenting the report of a Spanish rightwing think tank (Corts, 2007), Aznar extolled an alliance between the right in

Colombia and the United States, urging the completion of Colombias freetrade agreement with the United States and censuring its critics as a risk to

democracy itself (Aznar, 2007). Similarly, five days after the summit, Evo

Morales denounced a plot against his government involving USAID, a

Colombian paramilitary group, and, once again, Aznars Partido Popular.

The underlying reason for the confrontation lay in the expanding role of

Spanish multinationals (the so-called new conquistadores, according to many

popular movements); the freedom agenda is really to assert the rights of

these and other European multinationals in the region, to guarantee the flow of

profits. Spanish investments surged from 1993 on, concentrated in the banking

sector, oil and gas exploration, telecommunications, and other privatized utilities, from which they were by 2008 drawing over US$10 billion in annual profits. Aznars agenda for freedom signals a concern with, in fact, the freedom

of the investor. His report condemned all forms of state expropriation as a

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 199

powerful disincentive factor for investors and advocated respect for the

rights of property and a capacity to ensure the legal security of investments

above all else (Corts, 2007: 56): Every citizen or corporation must have its

property rights guaranteed and contracts freely entered into fulfilled, appealing as necessary to independent tribunals. The States attack on property rights,

without making any distinction between citizens and national or foreign corporations, is ever present in the new populism that constitutes socialism of the

twenty-first century. The socially harmful consequences of privatization

were of course not addressed by Aznar. It was left to Ortega to give voice to the

groundswell of opposition in Nicaragua to the Spanish utility company Unin

Fenosa, which had been responsible for cutting off communities unable to pay

its exorbitant rates and demanding compensation from local authorities even

when it had not supplied any service to them (Tribunal Permanente de los

Pueblos, 2009). At odds, then, with the official image of Ibero-American harmony, there has been a growing battle over the terms of economic relations

between Spanish capital and Latin America.

Alongside Spains expansionist role, it is worth drawing attention to the

exceptionally high profitability of UK-held direct investments. In 2008 these

generated US$3.2 billion profits from their 2007 year-end investment position

of US$15.3 billion, a remarkable rate of return averaging 20.8 percent, considerably higher than the EU average (my calculation based on Eurostat, 2012). To

put it differently, holding just 5.9 percent of the EUs capital directly invested

in Latin America, UK companies nonetheless achieved 14.9 percent of the

annual profit. The primary reason for this exceptional profitability of

UK-sourced investments is their concentration in extractive industries that

have benefited from the price boom for minerals and oil driven by the demand

from China especially. Quite simply, the surplus profits from mining and

hydrocarbons have flowed back to London (and a handful of other financial

hubs) rather than being used for the benefit of the peoples of Chile, Colombia,

and Peru. The surplus profits from oil and mining are correctly identified by

Grinberg (2010) as a form of rent, akin to the ground rent of landowners on

agricultural lands, that can be transferred through taxation from the primary

sector to the rest of society, but what Grinberg strikingly avoids is the appropriation of ground rent by the multinational corporations. The conversion of

rent into corporate superprofits is, as I argue elsewhere (Higginbottom, 2011),

a defining characteristic of imperialism.

The current policy implications in terms of international relations have

become increasingly evident in the European Commissions concerted advocacy of free-trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties in the interests

of EU-based corporations. The unfolding of the EU strategy and the way it has

affected the division between the Andean countries is detailed by Latimer

(2012). Latimer shows that many investment treaties are already in place and

that, its pretensions to a more developmental ethos notwithstanding, the EUs

agenda has in practice proceeded in lockstep with a U.S. strategy for recovering from the setback of losing the FTAA and is directed to isolating efforts at

regional integration on Bolivarian terms. Once in place, these agreements will

provide a regime of accumulation that institutionalizes guarantees for sustained external transfers of surplus value.

200LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

Capitalist investment is not simply ownership of physical stock but a value

relation in which the investing party has a claim on future profits. When the

investment relation is international, the investments value is counted in the

national financial accounts of the originating country as an asset and in those

of the host country as a liability, a claim on future income (IMF, 1993: Chap. 23).

The aggregated individual investments of private property represent the international investment position of a nation. The financial account is important for

state monetary authorities not least because it indicates demand for the national

currency, as capital flows require currency exchange between the host and the

originating nation. In reality as well as in formal accounting terms, there has

been a huge increase in Latin American countries liabilities to foreign investors

expecting to draw future revenue from their investments. The conversion of

potential revenue to actual revenue is exactly what happened in the wake of

the 20082009 crisis.

Stagnation and crisis in their home markets have caused Spanish and

Portuguese banks and corporations to cash in some of the capital assets they

have built up in Latin America since the 1990s. Rathbone and Johnson (2012,

citing IE Business School, 2012: 22) report that, using mechanisms that they call

capital extraction, many European corporations have been releasing their

accumulated capital assets, either by sell-offs or by listing the subsidiary on the

host countrys stock exchange. Even after the sell-offs, the astonishing degree

to which Spanish capital in particular continues to benefit from its ongoing

extraction of surplus value is revealed in a corporate survey that found that by

2015, most of the 30 largest Spanish companies with operations in Latin America

expect revenues from the region to exceed those from home.

Interim Conclusions, Further Investigation, and Debate

This article has explored foreign investment stocks and flows as one of the

outward signs of dependency in the neoliberal phase of imperialism. The big

picture is that U.S. and European capital today own three times more of Latin

America than they did just 15 years ago. From the evidence presented it is reasonable to conclude that the basic tenet of the dependency thesis still holds:

Galeanos veins of Latin America are indeed still open. The new modernizers, pro-market writers like Reid, Edwards, and Fukuyama, talk up the positive

effects of FDI but obscure the profit motive that is its driving force. Despite the

claimed benefits of neoliberal globalization, Latin America remains not so

much a developing continent as one that is being actively underdeveloped by

the world capitalist system.

The data on income balance confirm that two very different FDI regimes

have crystallized in the Andean subregion. The analysis here, admittedly oversimplifying a complex picture, contrasts the Andean ALBA nations (Bolivia,

Ecuador, and Venezuela) with their non-ALBA neighbors (Chile, Colombia,

and Peru). The crux of the difference is that the ALBA countries have succeeded in increasing the proportion of surplus profits retained in their national

economies against that part captured by international capital. This marks a

shift in recovering sovereignty over natural resources and, while it is not yet

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 201

socialism, speaks at least to government commitment to social welfare and a

developmental state.

Notwithstanding the fact that further investigation of the effects of the offshore financial centers is required, the above analysis indicates that during the

neoliberal phase EU corporations are at least on a par with their U.S. counterparts as profiting from direct investments in Latin America. Contemporary

imperialism in Latin America is not just about U.S. domination; it is also about

that of Spain, the UK, and the rest of Europe. As Latimer (2012) has pointed

out with special reference to Colombia and the Andean region, the United

States, Canada, and Europe are in the main working in harness as they aggressively pursue investment treaties and free-trade agreements. Their corporations are in a real commercial competition, but at the same time they cooperate

within a neoliberal institution-forming and agenda-setting framework that

works for them.

There are several directions in which these conclusions could be deepened,

refined, and modified. First, the emphasis on quantitative aspects has meant no

qualitative analysis of the social and environmental effects of foreign investment. Secondly, the overview needs to be filled in with a picture of investment

strategies and targeted sectors and any differentiation in strategy between the

United States and Europe. Reports by UNCTAD (2012a) and ECLAC (2012a)

address this issue, but there remains a gap between quantitative macro studies

and more qualitative sectoral or micro case studies.

The third and fourth directions are really challenges to my main conclusions,

for they concern ways in which FDI is changing that have not been addressed

here, notably the rise of Latin American transnational corporations and the

arrival of China as an investment source. The rise of the trans-Latins and

Chinas interest have a common characteristic, participation in the superprofits

possible in the extractive sector while the commodities boom continues. In the

space of one article it is not possible to do a full, multilayered analysis, and in

particular no analytical detail is offered of investment trends in the two biggest

economies, Brazil and Mexico, both homes to the new generation of transLatin corporations. The transfers from the two largest Latin American economies are present in the aggregate data because of their proportionate weight,

and in that respect at least they are part of the general pattern of investment

and profit flows. The emergence of China as a significant investor has already

generated much commentary, including the notion of the dragon in the room

(Gallagher and Porzecanski, 2010), and its role is a major development that

needs to be analyzed. These caveats notwithstanding, this article specifically

addresses a real gap in the contemporary literature. In this last section I start to

draw out the political consequences of the economic trends that have been

described with the aim of generating a broader discussion.

It is not only the U.S. eagle overhead and the Asian dragon at the door but

the European elephant in the room that we should be concerned about. The

idea that imperialism in Latin America is almost entirely about the United

States still pervades radical analysis (see, e.g., Dominguez, Lievesley, and

Ludlam, 2011), but there is no evidence that for Latin Americans on the ground

European investment is preferable to U.S. investment.

202LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

There is a separate reason for identifying the stake of corporate Europe in

Latin America from the point of view of class alliances and international solidarity with working-class, poor peasant, and indigenous social movements

confronting the foreign companies that dominate their lives and the domestic

governments dependent on them. Their embrace of dependency on FDI at all

costs orients states strategically against citizens who are opposed to the investment projects. Let down and criminalized by their own entreguista regimes,

Latin American social movements have been fighting the takeover of European

multinationals across all sectors but especially against the community dispossession and environmental destruction generated by extractive industries and

the unaffordable consequences of the privatization of public utilities. Social

movements have purposefully linked up with solidarity groups to project their

social resistance into the corporations home countries (for analysis see

Higginbottom, 2008; 2010, and for examples visit the web sites of Ecologistas

en Accin in Spain, the Colombia Solidarity Campaign in the UK, and the

bicontinental network Enlazando Alternativas).2

Another area to evaluate is any qualitative difference between European and

U.S. imperialism at the military-strategic level. Defending the strategic interests of European capital in Latin America is far from needing an independent

military presence in the region, whether or not the EU has the capacity to act in

such a united way. First, despite the social-movement campaigns and even

when Argentinas Repsol YPF nationalization is taken into account alongside

the nationalizations of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, the opposition does

not amount to a generalized regional offensive against the multinationals. On

the contrary, most governments, including the pink giant Brazil, still see FDI as

a cornerstone of their development strategy. Secondly, European capital is, like

U.S. capital, enjoying the benefit of the International Center for the Settlement

of Investment Disputes, which is already policing its interests quite effectively.

This indicates an international institutional regime that works for the benefit of

invested capital in general, most of which still comes from the global North.

Thirdly, the U.S. military presence has also directly benefited European-based

extractive corporations. The flow of outgoing profits has been so large that

Europe has in the main had no need to challenge the United States and transform commercial competition into state-led rivalries, the so-called banana wars

notwithstanding. Mainstream politics in Europe has followed Washington on

the major calls, considering Colombia a democracy despite two generations

of state-inspired dirty war, accepting the constitutional coups in Honduras and

Paraguay, attempting to divide and isolate ALBA, and so on. Fourthly, and

with less stigma than the United States after the defeat of its grandiose FTAA

project in 2005, Europe has been able to present corporate economic interests

in the guise of bilateral cooperative development. Finally, one should not rule

out a possible role for military intervention from certain expeditionaryequipped European states, including special operations should the need arise,

as the UK has done in the Falklands/Malvinas war and in Colombia. Overall,

though, European capital has for two decades been able to pursue its interests

without resorting to such methods, primarily through the programmatic insistence on free trade and investment.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 203

In the view of Robinson (2008), it no longer makes sense to conceive of

European capital or national capital as general categories. He argues that

globalization marks the transition to an entirely new epoch in the capitalist

mode of production in which the transnationalization of capital, the state, and

the dominant class are all substantive characteristics. Robinson overextrapolates from certain real tendencies in neoliberal globalization and understates

the significant continuities with earlier phases of imperialism. He poses a number of theoretical challenges, but his dismissal of both Lenins (1964 [1917]) and

Hilferdings (1981 [1910]) framing of imperialism and the dependency thesis as

concerned exclusively with external rather than internal class relations is quite

inaccurate. It fails to appreciate the systems-analytical depth of Marini and

other scholars who understand dependency as constructed through specific

capitalist class relations. Robinson misses an essential side of Lenins analysis

that the monopoly capitals (multinationals) of the great powers were in competition for superprofits extracted from colonial and semicolonial territories,

lands, and peoples. Lenin theorized what today would be termed the NorthSouth divide as systemically reproduced by and constitutive of capitalism as

imperialism. The hostile brothers of capitalism only become really hostile to the

point of war when in a crisis one or another no longer has access to the superprofits drawn from the global South, but, as we have seen, both the United

States (Canada also) and the EU have been able to enjoy stupendous profits

from Latin America through its opening up during the neoliberal period.

Again, the entry of China into the picture could change it significantly in the

direction of increased geostrategic rivalry, although how that will work out is

as yet unclear.

There are many new dimensions in the dialectic of domination and dependency at work in Latin America. What this article specifically brings out is that

a strategy to defend and advance progressive change has to contend with

European capital as well as U.S. capital. The specter of twenty-first-century

socialism haunts Europe as well as the United States in that it is a challenge to

the global capitalist systemimperialismitself.

Notes

1. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPSwwmB_oOY.

2. See, respectively, http://www.ecologistasenaccion.org/, http://www.colombiasolidarity.

org.uk?, and http://www.enlazandoalernativas.org.

References

Aznar, Jos Mara

2007 Discurso ntegro de Jos Mara Aznar en Bogot, 14 November 2007. http://www.

libertaddigital.com/nacional/discurso-integro-de-jose-maria-aznar-en-bogota-1276317477/

(accessed September 19, 2012).

Banco de Espaa

2012 Balanza de pagos y posicin de inversin internacional de Espaa, 2011. http://www.

bde.es/bde/es/secciones/informes/Publicaciones_an/Balanza_de_Pagos/anoactual/

(accessed September 19, 2012).

Brcena, Alicia and Daniel Titelman

2009 ECLACs contribution to analysis on the economic and financial crisis. http://www.

un.org/regionalcommissions/crisis/eclaccon.pdf (accessed September 19, 2012).

204LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis)

2012a U.S. direct investment abroad: country and industry detail for financial outflows.

http://www.bea.gov/international/xls/fin_10.xls (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012b U.S. direct investment position abroad on a historical-cost basis. http://www.bea.

gov/international/xls/usdiapos10.xlsx (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012c U.S. direct investment abroad: income without current-cost adjustment. http://www.

bea.gov/international/xls/inc_10.xls (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012d U.S. direct investment abroad: reinvested earnings without current-cost adjustment.

http://www.bea.gov/international/xls/re_10.xls (accessed September 19, 2012).

Chilcote, Ronald H. (ed.).

2003 Development in Theory and Practice: Latin American Perspectives. Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield.

Corts, Miguel ngel

2007 Amrica Latina: una agenda de libertad. Fundacin FAES, Madrid. http://www.

fundacionfaes.org/ (accessed April 30, 2010).

Dominguez, Francisco, Geraldine Lievesley, and Steve Ludlam (eds.).

2011 Right-Wing Politics in the New Latin America: Reaction and Revolt. London: Zed Press.

Dussel, Enrique

2001 Towards an Unknown Marx: A Commentary on the Manuscripts of 186163. London and New

York: Routledge.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean)

2009 Anuario estadstico de Amrica Latina y el Caribe, 2009. http://websie.eclac.cl/

anuario_estadistico/anuario_2009/eng/default.asp (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012a Foreign direct investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2011. http://www.

cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/2/46572/LIE2011-Chapter2.pdf (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012b Estadsticas e indicadores. http://websie.eclac.cl/infest/ajax/cepalstat.asp?carpeta=

estadisticas (accessed September 21, 2012).

Edwards, Sebastien

2009 Latin Americas decline: a long historical view. NBER Working Paper Series 15171.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w15171 (accessed April 3, 2010).

2010 Left Behind: Latin America and the False Promise of Populism. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Eurostat

2010 European Union direct investments: Eurostat Metada. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.

eu/cache/ITY_SDDS/en/bop_fdi_esms.htm (accessed September 19, 2012).

2012 European Union direct investments: main indicators. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa

.eu/(accessed September 19, 2012).

Fukuyama, Francis (ed.).

2008 Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap between Latin America and the United States.

Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Gallagher, Kevin and Roberto Porzecanski

2010 The Dragon in the Room: China and the Future of Latin American Industrialization. Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press.

Grinberg, Nicolas

2010 Where is Latin America going?: FTAA or twenty-first-century socialism? Latin

American Perspectives 37 (1): 185202.

Harrison, Graham

2010 Neoliberal Africa: The Impact of Global Social Engineering. London and New York: Zed Press.

Higginbottom, Andy

2008 Solidarity research as methodology: the crimes of the powerful in Colombia. Latin

American Perspectives 35 (5): 158170.

2010 Popular tribunals and international strategy, pp. 182-205 in Mario Novelli and Anibel

Ferus-Comelo (eds.),Globalisation, Knowledge, and Labour. London: Routledge.

2011 Gold mining in South Africa reconsidered: new mode of exploitation, theories of imperialism, and Capital. conomies et Socits 45: 261288.

Hilferding, Rudolf

1981 (1910) Finance Capital: A Study of the Latest Phase of Capitalist Development. London: Routledge

and Kegan Paul.

Higginbottom / Foreign Investment in Latin America 205

Ibarra, Marilyn and Jennifer Koncz

2009 Direct investment positions for 2008: country and industry detail, pp. 2033 in Survey

of Current Business July 2009. Washington, DC: BEA. http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2009/07%20

July/0709_dip.pdf (accessed September 19, 2012).

IE Business School

2012 2012: panorama de inversin espaola en Latinoamrica. IE Business School, V Informe,

Madrid, February. http://www.infolatam.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Informe-ie-2012.

pdf (accessed November 19, 2012).

IMF (International Monetary Fund)

1993 Balance of payments manual: Fifth edition. http://www.imf.org/external/np/sta/

bop/bopman.pdf (accessed September 19, 2012).

Kay, Cristobal

1989 Latin American Theories of Development and Underdevelopment. London and New York:

Routledge.

Kirby, Peadar

2009 Neo-structuralism and reforming the Latin American state: lessons from the Irish case.

Economy and Society 38 (1): 132153.

Latimer, Amanda

2012 States of sovereignty and regional integration in the Andes. Latin American Perspectives

39 (1): 7895.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich

1964 (1917) Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism: a popular outline, pp. 185304 in

Collected Works, Vol. 22. Moscow and London: Progress/Lawrence and Wishart.

Marini, Ruy Mauro

1973 Dialectica de la dependencia. Mexico City, Ediciones Era.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)

2001 Glossary of statistical terms. http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1028

(accessed September 19, 2012).

Prez Caldentey, Esteban and Matas Vernengo

2008 Back to the Future: Latin Americas Current Development Strategy. Santiago, Chile: ECLAC.

ProExport Colombia

2012 Colombian economy: FDI key statistics. http://www.investincolombia.com.co/colombiaeconomy (accessed September 19, 2012).

Rathbone, John Paul and Miles Johnson

2012 Latin America a gold mine for Europeans. Financial Times, November 11.

Rebossio, Alejandro

2012 Cmo impactan las nacionalizaciones en la inversin extranjera? El Pais, April 19.

Reid, Michael

2007 Forgotten Continent: The Battle for Latin Americas Soul. New Haven and London: Yale

University Press.

Robinson, William I.

2008 Latin America and Global Capitalism: A Critical Globalization Perspective. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Rostow, Walt Whitman

1990 (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. 3d edition. Cambridge

and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Santos, Theotnio dos

1970 The structure of dependence. American Economic Review 60: 231236.

Shaxson, Nicholas

2011 Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World. London: Bodley Head.

Smith, John C.

2010 Imperialism and the globalization of production. Ph.D. diss., University of Sheffield.

Sotelo Valencia, Adran

2005 Amrica Latina, de crisis y paradigmas: La teora de la dependencia en el siglo XXI. Mexico City:

Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico.

Stanley, Leonardo

2008 Natural Resources and Foreign Investors: A Tale of Three Andean Countries. Medford, MA:

Tufts University Working Group on Development and Environment in the Americas. http://

ase.tufts.edu/gdae/Pubs/rp/DP16StanleyApr08.pdf (accessed November 19, 2012).

206LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES

Tribunal Permanente de los Pueblos

2009 Audiencia centroamericana sobre la deuda ecolgica, histrica, social, econmica de

pases europeos con Centro Amrica: dictamen del jurado. http://www.ecoportal.net/Temas

_Especiales/Derechos_Humanos/la_deuda_ecologica_social_y_economica_de_europa_con

_centroamerica (accessed September 19, 2012).

Tsolakis, Andreas

2011 Multilateral lines of conflict in contemporary Bolivia, pp. 130147 in Francisco

Dominguez, Geraldine Lievesley, and Steve Ludlam (eds.), Right-Wing Politics in the New Latin

America: Reaction and Revolt. London: Zed Press.

UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development)

2009 Country fact sheets. http://www.unctad.org/ (accessed April 3, 2010).

2010 World Investment Report 2009: Transnational Corporations, Agricultural Production, and

Development. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

2012a World Investment Report 2012: Towards a New Generation of Policies. New York and Geneva:

United Nations.

2012b Country fact sheets. http://www.unctad.org/ (accessed September 19, 2012).

Wallis, Daniel and Mariela Paranga

2012 Analysis: Chavez win keeps Venezuela oil policy intact. http://www.reuters.com/

article/2012/10/08/us-venezuela-election-oil-idUSBRE8970UR20121008 (accessed December

17, 2012).

Woodward, David

2001 The Next Crisis? Direct and Equity Investment in Developing Countries. London and New York:

Zed Books.

World Bank

2012 Data: GDP growth (annual %). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.

KD.ZG/countries/ (accessed September 19, 2012).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Cómo Copiar Un Texto de Una Página Web ProtegidaDocument4 paginiCómo Copiar Un Texto de Una Página Web ProtegidaBrendiiz Antonio Santiago40% (10)

- Una teoría sobre el capitalismo global: Producción, clase y Estado en un mundo transnacionalDe la EverandUna teoría sobre el capitalismo global: Producción, clase y Estado en un mundo transnacionalEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Examen Parcial Gerencia de Desarrollo Sostenible 1Document25 paginiExamen Parcial Gerencia de Desarrollo Sostenible 1PauDanyNicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ciencia y Tecnología en El PeruDocument41 paginiCiencia y Tecnología en El Perumirev25100% (1)

- Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional ActualizadoDocument216 paginiPlan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional ActualizadoTino Carrasco GalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Evolución Sostenible (II)Document124 paginiLa Evolución Sostenible (II)allartean1232100% (1)

- Resumen de America Latina, Política y Sociedad TouraineDocument10 paginiResumen de America Latina, Política y Sociedad TouraineDanytza González CeballosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midiendo El Valor CompartidoDocument28 paginiMidiendo El Valor CompartidoDiego A. GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Actualidad Economica y Politica Del MundoDocument7 paginiLa Actualidad Economica y Politica Del MundoLauraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enumere Algunos Ganadores y Algunos Perdedores de La Globalización en Su Entorno InmediatoDocument1 paginăEnumere Algunos Ganadores y Algunos Perdedores de La Globalización en Su Entorno InmediatoBryan VeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 286 Nueva SociedadDocument140 pagini286 Nueva SociedaddanielemiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tema 66. Intedependencias y Desequilibrios en El Mundo Actual. Desarrollo y Subdesarrollo. Desarrollo SostenibleDocument7 paginiTema 66. Intedependencias y Desequilibrios en El Mundo Actual. Desarrollo y Subdesarrollo. Desarrollo SostenibleAlbaPalaciosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adrián Lajous Martínez. Desarrollo, deuda y comercio: un testimonio histórico sobre la crisis económica mexicana y el ajuste, 1983-1993De la EverandAdrián Lajous Martínez. Desarrollo, deuda y comercio: un testimonio histórico sobre la crisis económica mexicana y el ajuste, 1983-1993Încă nu există evaluări

- Los 100 Días de Milei: Una Política Exterior Al Servicio de Las CorporacionesDocument16 paginiLos 100 Días de Milei: Una Política Exterior Al Servicio de Las CorporacionesEnOrsaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proyecto de Tesis - Administración - Inversión Pública y Desarrollo Económico - Maestría - JHONNY LAZO - UNCP - Enero 2018Document66 paginiProyecto de Tesis - Administración - Inversión Pública y Desarrollo Económico - Maestría - JHONNY LAZO - UNCP - Enero 2018Luis Alberto Lazo GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Globalizacin Sus Efectos y BondadesDocument13 paginiLa Globalizacin Sus Efectos y Bondadesapi-178097299100% (1)