Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ludwig Van Beethoven: A Mason by Acts and Words

Încărcat de

Paul CanniffDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ludwig Van Beethoven: A Mason by Acts and Words

Încărcat de

Paul CanniffDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Final Text, April 5, 2002

Ludwig van Beethoven: A Mason by Acts and Words

Brethren,

My presentation this evening is drawn from a paper entitled Beethoven, Freemasonry,

and the Tagebuch of 1812-1818 by Maynard Solomon. The paper was originally

published in 2000 in an academic journal called the Beethoven Forum by the University

of Illinois Press. While that journal deals mainly in musicology, this article is a rare find

in its extremely detailed examination of Beethovens role in Freemasonry. You will find

that original paper available for download in PDF format from our intranet site. Tonight

I intend only to provide a survey of its forty-six pages and some analysis derived from it.

In the pursuit of those in history who may act as icons of our Craft, we are often

challenged by what appear to be contradictions or gaps in official history. To the casual

observer this marks the triteness of Masonic research. Even scholars who are well

disposed towards Freemasonry regard these problems with a gimlet eye. Alexander

Piatigorsky, author of Freemasonry: A Study of a Phenomenon, notes that no other

organization has been so perplexed in trying to examine itself and reveal unto itself its

origins.

On the question of Ludwig van Beethoven and his role in Masonry, we have to bear in

mind that he lived in a time in which the practice of the Craft was uncertain, even

dangerous. As Europe swung wildly between embracing and oppressing Freemasonry,

records were destroyed or scattered as lodges were dismantled; writings were suppressed

out of well-founded fear of persecution; and governments were not shy about sweeping

embarrassing moments under the carpet of secrecy.

In the 1770s Freemasonry benefited from the patronage of ruling monarchs in Germany

and Austria. Some like Emperor Joseph II of Austria actually saw Masonry as a useful

philosophy in promoting limited political and social reforms. But it was the American

and French Revolutions that changed all this. Monarchs and their ministers began to

distrust any secret society. The all-embracing approach of the Craft towards matters of

faith naturally encouraged membership from anti-clerical intellectuals. Consequently

German Freemasonry was effectively halted by 1788 and in Austria the Craft was

outlawed by December 1793. Only a handful of so-called patriotic lodges were permitted

by the state to exist in Austria. In Germany many Masons flocked to newly sprung

reading societies or Lesegesellschaft, which promoted enlightened thought and literature.

The society in Bonn actually commissioned several musical works from Beethoven, one

being a cantata to mark the death of Joseph II, who was indeed a Mason.

Against this backdrop we need to weigh two points. Maynard Solomon states that

Beethovens name cannot be located on the registers of any Masonic lodge or other

fraternal body. Yet in the same paragraph he quotes Karl Holz, a personal assistant to

Beethoven and authorized biographer who wrote:

Beethoven was a Freemason, but not active in later years

Page 1 of 4

Final Text, April 5, 2002

Though Holzs statement may not be supported by evidence like a dues card, it is

possible to conjecture that such evidence could have gone astray in those chaotic times.

So, we are forced to draw conclusions from other evidence. A good starting point would

be Beethovens devotion to the works of German poet and Mason Friedrich Schiller.

Consider these excerpts from the Ode to Joy, the text of the concluding chorale of

Beethovens Ninth Symphony:

Joy, fair spark of the gods,

Daughter of Elysium,

Drunk with fiery rapture, Goddess,

We approach thy shrine!

Thy magic reunites those

Whom stern custom has parted;

All men will become brothers

Under thy gentle wing.

Be embraced, Millions!

Take this kiss for all the world!

Brothers, surely a loving Father

Dwells above the canopy of stars.

Do you sink before him, Millions?

World, do you sense your Creator?

Seek him then beyond the stars!

He must dwell beyond the stars.

Some of the Masonic imagery within that text is strikingly self-evident. But such

imagery occurs a number of times within Beethovens compositions and his letters.

Beethovens opera Fidelio expresses his devotion to the sentiments of liberty, freedom

of conscience and republican ideals, as a wrongly imprisoned man is brought from the

dark of captivity to the light of freedom. Some musical scholars note similarities

between this opera and Mozarts The Magic Flute. According to Edward Dent, an expert

in Mozarts operas,

Florestan and Leonora [Beethovens hero and heroine] are Tamino and

Pamina grown up and facing the fire and water of our own world.

In a reversal from The Magic Flute, in Fidelio it is the heroine who must undergo trials in

order to be reunited with her persecuted lover.

The most telling point in this is that the first producer of Fidelio was Emmanuel

Schikaneder, a Mason and close collaborator with Mozart who wrote the libretto for The

Page 2 of 4

Final Text, April 5, 2002

Magic Flute. Schikaneder was part of the Mozart Circle that produced other esoteric

works with Masonic themes, such as The Philosophers Stone and The Beneficent

Dervish.

Schikaneder proves to be only one of many Masonic friends of Beethoven. The court

organist Christian Gottlob Neefe, who was Beethovens main composition teacher and

his immediate superior in the court chapel, headed one lodge of Illuminati in Bonn in

1784. Many other court musicians who were early influences in Beethovens musical life

belonged to that lodge. The statutes of the lodge forbade students from membership, but

it is reasonable to conjecture of Beethovens exposure to Masonic principles through

those brethren.

Certainly later written evidence bears this out. In a mid-1790s letter to his close friend,

the Mason Franz Gerhard Wegeler, Beethoven wrote,

I guarantee that the new temple of sacred friendship which you will erect upon

these qualities, will stand firmly and forever, and that no misfortune, no temple

will be able to shake its foundations.

In 1810 he wrote to Wegeler,

I am told that in your Masonic Lodges you sing a song composed by me,

presumably in E flat major, which I myself do not possess. Do send it to me.

In other letters of the period we find him employing repeatedly the phrases beloved and

worthy brother and worthy brother.

The author Maynard Solomon reveals considerably more in his examination of the

Tagebuch, a daily journal kept by Beethoven from 1812 to 1818. At various points,

Beethoven explicitly uses the Masonic calendar system, Anno Lucis, in dating events. In

an early 1816 entry he writes that

Our world history has now lasted for 5816 years

In early 1818 he writes that

Our consciousness on our planet is now calculated as 5818 years.

It is not by accident that he uses the Masonic convention of commencing dates from 4000

B.C.

The explicitness of the Masonic symbolism in his writings varies. In an 1824 letter to a

music dealer he writes,

Page 3 of 4

Final Text, April 5, 2002

Give Herr Ries, the bearer of this not, some easy compositions for piano-forte

duet at a good price or even better free of charge Behave according to the

purified doctrine All good wishes

Now contrast this with a remark in the sketches for the Adagio of his Razumovsky

Quarter, op. 59, no. 1:

A weeping willow or acacia tree on my brothers grave.

Master Masons will certainly recognize the symbolism of the acacia tree, but the weeping

willow does confuse what would be seen as purely Masonic.

Half of the Solomon paper is in fact a detailed examination of the Tagebuch, which is rife

with references to Egyptian ritual, oriental philosophy, discussion of earlier poetical

works about the Knights Templar, and the initial rituals of the Order of the Illuminati.

Taken altogether, Solomon provides considerable evidence of how the symbolism of

Freemasonry lent to Beethoven a means of expressing himself in matters both esoteric

and practical. Beethoven was better informed of higher purposes through the arcane

imagery of the Craft, and his commitment to rational thinking and republican government

was strengthened through a purer understanding of fraternity.

I would submit that in contrast to the author, one with more intimate knowledge of the

Craft would be more forgiving of the murkiness surrounding Beethovens actual

membership in the Craft. That being said, I commend Maynard Solomons paper to your

attention.

Page 4 of 4

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mozart & His Masonic MusicDocument4 paginiMozart & His Masonic MusicJulio GuillénÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dunning. Mozart and SalieriDocument4 paginiDunning. Mozart and Salieristefanpopescu574804Încă nu există evaluări

- Josephine's Composer: The Life Times and Works of Gaspare Pacifico Luigi Spontini (1774-1851)De la EverandJosephine's Composer: The Life Times and Works of Gaspare Pacifico Luigi Spontini (1774-1851)Încă nu există evaluări

- Eighteenth Century Scandinavian Composers, Vol. XDe la EverandEighteenth Century Scandinavian Composers, Vol. XÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Freethinker: Elihu Palmer and the Struggle for Religious Freedom in the New NationDe la EverandAmerican Freethinker: Elihu Palmer and the Struggle for Religious Freedom in the New NationÎncă nu există evaluări

- MozartDocument8 paginiMozartcarloskohatsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bach and Baroque: European Source Materials from the Baroque and Early Classical Periods With Special Emphasis on the Music of J.S. BachDe la EverandBach and Baroque: European Source Materials from the Baroque and Early Classical Periods With Special Emphasis on the Music of J.S. BachÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mineralogy and Magic Flute by MozartDocument28 paginiMineralogy and Magic Flute by MozartTomaso Vialardi di Sandigliano100% (3)

- Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)De la EverandSoliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Parsifal A Mystical Drama By Richard Wagner Retold In The Spirit Of The Bayreuth InterpretationDe la EverandParsifal A Mystical Drama By Richard Wagner Retold In The Spirit Of The Bayreuth InterpretationEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Later Eighteenth Century French Composers, Vol. XVDe la EverandLater Eighteenth Century French Composers, Vol. XVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letters of Felix Mendelssohn to Ignaz and Charlotte MoschelesDe la EverandLetters of Felix Mendelssohn to Ignaz and Charlotte MoschelesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letters of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy from Italy and SwitzerlandDe la EverandLetters of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy from Italy and SwitzerlandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sacred Music, 110.3, Fall 1983 The Journal of The Church Music Association of AmericaDocument25 paginiSacred Music, 110.3, Fall 1983 The Journal of The Church Music Association of AmericaChurch Music Association of AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frank Sewall The CHRISTIAN HYMNAL Hymns With Tunes Philadelphia 1867Document249 paginiFrank Sewall The CHRISTIAN HYMNAL Hymns With Tunes Philadelphia 1867francis battÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secretaries of The Metropolitan CollegeDocument2 paginiSecretaries of The Metropolitan Collegealistair9100% (1)

- MOZART and MasonryDocument12 paginiMOZART and MasonryJesse GrossmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talks On Knights Templar MasonryDocument1 paginăTalks On Knights Templar MasonryGlenn FarrellÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1888 Speth Ars Quatuor Coronatorum v1Document280 pagini1888 Speth Ars Quatuor Coronatorum v1Paulo Sequeira Rebelo100% (2)

- Corbin - On The Meaning of Music in Persian MysticismDocument3 paginiCorbin - On The Meaning of Music in Persian MysticismKeith BroughÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eemasonry in SloveniaDocument17 paginiEemasonry in SloveniaJuanitoGuadalupe100% (1)

- Pe. William Francis Xavier Stadelman, C.S.sp. - Glories of The Holy GhostDocument608 paginiPe. William Francis Xavier Stadelman, C.S.sp. - Glories of The Holy GhostCarlosJesusÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Life and Works of Turlough O Carolan PDFDocument5 paginiThe Life and Works of Turlough O Carolan PDFClaudia AliottaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salome AnalysisDocument3 paginiSalome AnalysisJohn WilliamsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rake's ProgressDocument14 paginiThe Rake's ProgressAleÎncă nu există evaluări

- MoaazrtreDocument22 paginiMoaazrtreChrist KorÎncă nu există evaluări

- John XXII Docta Sanctorum Patrum PDFDocument2 paginiJohn XXII Docta Sanctorum Patrum PDFrichgr1123Încă nu există evaluări

- History of FreemasonryDocument18 paginiHistory of FreemasonrysdjfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Johann Mattheson GroveDocument8 paginiJohann Mattheson GroveSergio Miguel MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Borghi 64 CadenzasDocument24 paginiBorghi 64 Cadenzasalana100% (1)

- Catholic Music in The Diocese of Augsburg C. 1600: A Reconstructed Tricinium Anthology and Its Confessional ImplicationsDocument58 paginiCatholic Music in The Diocese of Augsburg C. 1600: A Reconstructed Tricinium Anthology and Its Confessional ImplicationspaulgfellerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards An Allegorical Interpretation of Buxtehude's Funerary CounterpointsDocument25 paginiTowards An Allegorical Interpretation of Buxtehude's Funerary CounterpointsCvrator HarmoniaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 100 Best Baroque (CD)Document13 pagini100 Best Baroque (CD)cisco012Încă nu există evaluări

- Works: 1761-1766: K K Composition Date PlaceDocument32 paginiWorks: 1761-1766: K K Composition Date PlacePepe PaezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prog 175818Document24 paginiProg 175818GanzamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Secret Subscribers To C. P. E. Bach's Oratorio Die Israeliten GreerDocument19 paginiThe Secret Subscribers To C. P. E. Bach's Oratorio Die Israeliten GreermordidacampestreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quant Je Voi Yver RetornerDocument1 paginăQuant Je Voi Yver RetornerKAWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Masons On StageDocument39 paginiMasons On StageIlluminhate100% (1)

- Apology Demanded From Spencer & CoDocument5 paginiApology Demanded From Spencer & Coalistair9Încă nu există evaluări

- Song and Dance Music in The Middle AgesDocument10 paginiSong and Dance Music in The Middle AgesmusicatworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pamela Jones Fitzwilliam Virginal BookDocument96 paginiPamela Jones Fitzwilliam Virginal BookRobert HillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Galilei, Michelangelo - Primo LibroDocument76 paginiGalilei, Michelangelo - Primo LibroLeandro MarquesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Persian Bayan of Mirza Ali Muhammad Shirazi BabDocument73 paginiThe Persian Bayan of Mirza Ali Muhammad Shirazi BabrcheraliteÎncă nu există evaluări

- She Descended On A Cloud From The Highes PDFDocument22 paginiShe Descended On A Cloud From The Highes PDFRoger BurmesterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strauss' Salome - Tasteless?Document7 paginiStrauss' Salome - Tasteless?Kai WikeleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Morley, A Plaine Thomas MorleyDocument7 paginiThomas Morley, A Plaine Thomas Morleypetrushka1234Încă nu există evaluări

- BWV1007 1012 RefDocument15 paginiBWV1007 1012 RefjojojoleeleeleeÎncă nu există evaluări

- PM 127 Rose Croix and ChristianityDocument10 paginiPM 127 Rose Croix and ChristianityJuLio LussariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ordo Virtutum: The of Hildegard o F BingenDocument152 paginiOrdo Virtutum: The of Hildegard o F BingenFulvidor Galté OñateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding The 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis: Lessons For Scholars of International Political EconomyDocument23 paginiUnderstanding The 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis: Lessons For Scholars of International Political EconomyLeyla SaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Laws On The Professionalization of Teaching PD 1006 Edited Oct 11 2019Document6 paginiBasic Laws On The Professionalization of Teaching PD 1006 Edited Oct 11 2019Renjie Azumi Lexus MillanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fraud Detection and Deterrence in Workers' CompensationDocument46 paginiFraud Detection and Deterrence in Workers' CompensationTanya ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AQA GCSE Citizenship Revision Guide - FINALDocument19 paginiAQA GCSE Citizenship Revision Guide - FINALJohn SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

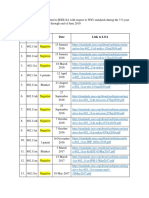

- WiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019Document3 paginiWiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019abdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promises During The Elections and InaugurationDocument3 paginiPromises During The Elections and InaugurationJessa QuitolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Term Financial Management 3rd Edition Maness Test BankDocument5 paginiShort Term Financial Management 3rd Edition Maness Test Bankjuanlucerofdqegwntai100% (16)

- 016 - Neda SecretariatDocument4 pagini016 - Neda Secretariatmale PampangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- United Capital Partners Sources $12MM Approval For High Growth Beverage CustomerDocument2 paginiUnited Capital Partners Sources $12MM Approval For High Growth Beverage CustomerPR.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consent To TreatmentDocument37 paginiConsent To TreatmentinriantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhammad Al-MahdiDocument13 paginiMuhammad Al-MahdiAjay BharadvajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis Condominium RulesDocument12 paginiAnalysis Condominium RulesMingalar JLSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eada Newsletter-May-2015 (Proof3)Document2 paginiEada Newsletter-May-2015 (Proof3)api-254556282Încă nu există evaluări

- KMPDU Private Practice CBA EldoretDocument57 paginiKMPDU Private Practice CBA Eldoretapi-175531574Încă nu există evaluări

- VergaraDocument13 paginiVergaraAurora Pelagio VallejosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Csec Physics Study ChecklistDocument10 paginiCsec Physics Study ChecklistBlitz Gaming654100% (1)

- Avengers - EndgameDocument3 paginiAvengers - EndgameAjayÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5.opulencia vs. CADocument13 pagini5.opulencia vs. CARozaiineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bdo Cash It Easy RefDocument2 paginiBdo Cash It Easy RefJC LampanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transmittal of Documents To TeachersDocument15 paginiTransmittal of Documents To TeachersPancake Binge&BiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moovo Press ReleaseDocument1 paginăMoovo Press ReleaseAditya PrakashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjusting Entries - Sample Problem With AnswerDocument19 paginiAdjusting Entries - Sample Problem With AnswerMaDine 19100% (3)

- HNC Counselling ApplicationFormDocument3 paginiHNC Counselling ApplicationFormLaura WalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1625718679.non Teaching Applicant ListDocument213 pagini1625718679.non Teaching Applicant ListMuhammad Farrukh HafeezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09-01-13 Samaan V Zernik (SC087400) "Non Party" Bank of America Moldawsky Extortionist Notice of Non Opposition SDocument14 pagini09-01-13 Samaan V Zernik (SC087400) "Non Party" Bank of America Moldawsky Extortionist Notice of Non Opposition SHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Încă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of SupportDocument3 paginiAffidavit of Supportprozoam21Încă nu există evaluări

- Welcome To HDFC Bank NetBankingDocument1 paginăWelcome To HDFC Bank NetBankingsadhubaba100Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Report On The Audit of Peace Corps Panama IG-18-01-ADocument32 paginiFinal Report On The Audit of Peace Corps Panama IG-18-01-AAccessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allied Banking Corporation V BPIDocument2 paginiAllied Banking Corporation V BPImenforever100% (3)

- Certificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsDocument9 paginiCertificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsMARLON TABACULDEÎncă nu există evaluări