Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Deathly Otherness in Pātañjala-Yoga by Yohanan Grinshpon PDF

Încărcat de

Cecco AngiolieriTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Deathly Otherness in Pātañjala-Yoga by Yohanan Grinshpon PDF

Încărcat de

Cecco AngiolieriDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Silence Unheard: Deathly Otherness in Ptajala-Yoga by Yohanan Grinshpon

Review by: Lola Williamson

The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Feb., 2004), pp. 226-227

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4133355 .

Accessed: 16/10/2014 05:29

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 151.100.161.185 on Thu, 16 Oct 2014 05:29:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

226

THE JOURNAL

OF ASIAN STUDIES

dismantle the unjust social order through struggle. Other strands emphasize

reconstruction, employing technologies appropriate to the context and times.

Problems with this book could arise from the proselytizing nature of its arguments

and the presentation of the material. The authors are clearly aiming to create a new

field, and they have succeeded in doing so in some measure. But from the numerous

case studies and examples which the authors cite, one also gets a feeling of being

bombarded with information. Oftentimes the authors pick up the thread of an

argument and then get sidetracked into a welter of details, which blunts the force of

the argument. Nevertheless, the authors' deep and sincere concern about environmental degradation in India and their clear, logical analysis and formidable crossdisciplinary armature make this book a fundamental advance in our understanding of

environmental issues and problems. This book will certainly be widely read and

discussed by all of those interested in developing a better understanding about the

environmental problems of India, in all of their dimensions.

ABDUL JAMIL URFI

Universityof Delhi

Silence Unheard: Deathly Otherness in Pataiijala-Yoga. By YOHANAN

GRINSHPON.

Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. xii, 156

$54.50

$17.95 (paper).

(cloth);

pp.

The Yogaszitrahas been interpreted in many ways by scholars, yoga practitioners,

and gurus over the course of the two millennia since it was first written. Yohanan

Grinshpon proposes that none of these interpreters ultimately deal with the text's

antisocial, antilife message, nor do they address the text's inclusion of supernormal

powers (siddhis)as being central to the yogin'sreality. In other words, most interpreters

gloss over the radical "otherness"of the yogin's world.

The book is written for readers who are familiar with the Yogasfztratext as well

as its various commentaries. Although Grinshpon explains some technical terms such

as samddhiand kaivalya, his overarching purpose is not to explicate the text itself, but

to make observations about others' expositions of the text. He classifies these

commentators into eight archetypal categories: complacent outsider, ultimate insider,

romantic seeker, universal philosopher, bodily practitioner, mere philologist, classical

scholar, and observers' observer.

By referring to his own interpretation of the text as a myth, Grinshpon highlights

the fact that it is impossible to know the true intent of Patafijali, the purported author

The myth that Grinshpon imagines is this: Patafijali, a socialized,

of the Yogasz7tra.

intellectual scholar of an Indian dualistic philosophy (sdnkhyayoga) encounters an

emaciated, silent yogin who has, through intense discipline, not only broken all

contact with normal reality but has also created a new world for himself in which

flying through the air, understanding the language of animals, and walking on water

are normal occurrences. The goal of the yogin, according to Grinshpon, is

disintegration and dissolution, "a complete completion, infinitely deeper and more

final than death" (p. 2). The world of the yogin is unapproachable by all normal,

socialized human beings, including Patafijali. Not only is the required discipline too

severe for all but a very few but also the goal of that discipline is undesirable for

normal people who "wish to live on and on" (p. 35).

According to Grinshpon, attempts to understand the yogin's universe result in a

mirroring of one's own disposition. This is because the yogin's world is too far from

This content downloaded from 151.100.161.185 on Thu, 16 Oct 2014 05:29:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BOOK REVIEWS-SOUTH

ASIA

227

the observer's world. Only once, and briefly, does he concede that perhaps there is

some similarity between the yogin and the ordinary person. As he attempts to

understand the attraction of the Yogasltra to so many seekers and scholars, Grinshpon

admits that they must be looking for more than "narcissisticreflection." He contends,

"[a) more likely hypothesis would be the essential identity of the yogin's otherness

with one's innermost being" (p. 35).

Grinshpon's insistence on the extreme otherness of the yogic experience makes

his contribution to the ongoing discourse over the meaning of the Yogasfztraunique.

As well, his assertion that the text be looked at holistically, particularly without

discrediting the centrality of the siddhis to yogic experience, is rare. In this assertion

he agrees with the recent critique made by Ian Whicher in The Integrityof the Yoga

Darsana (State University of New York Press, 1998), which also contends that the

text should be viewed as a unified aggregate. However, this may be the only point

on which the two authors agree. Whereas Whicher sees the text as expounding a

system for achieving integration, Grinshpon sees a system for achieving disintegration;

whereas Whicher sees a map for attaining worldly happiness, Grinshpon sees a map

for attaining world-denying asceticism; whereas Whicher sees light, Grinshpon sees

darkness. (Grinshpon's references to darkness are numerous: for example, "the inner

... is dubious and dark" [p. 11, "the light of subjectivity becomes black" [p. 4], and

"the sunless world of the emaciated yogin's innerness" [p. 201.)

Although Grinshpon does not refer to Whicher's recent commentary, he would

undoubtedly include the author under the rubric of romantic seeker, along with

Mircea Eliade, Heinrich Zimmer, Georg Feuerstein, and others. Grinshpon places

himself in the category of observers' observer, that is, one who comments on others'

interpretations. Of his eight categories, none--except observers' observer-are able

to grasp the unbreachable chasm between the silent yogin and the vocal observer of

that yogin. Even the ultimate insider such as ParamahansaYogananda, whose book

Autobiographyof a Yogi (Los Angeles: Self-Realization Fellowship, 1946) is full of

anecdotes about himself and others that reveal the viability of siddhis, has no

comprehension of this gap. This is because, according to Grinshpon, Yogananda "looks

upon yogic experiences as extensions of ordinary ones .. ." (p. 17). One might think

that Yogananda's example as a well-acknowledged modern-day yogin who was socially

well adjusted would cause Grinshpon to reexamine his thesis that the lonely,

emaciated yogin, and the normal, socialized person have nothing in common.

Grinshpon has a fascination with archetypes, which may engender absorbing

mythology but may also be weak on explanatory power. The silent, dying yogin who

cannot communicate with ordinary people probably existed in Patafijali's time, as in

the present. Likewise, the intellectual philosopher who cannot access inner silence

also exists, but that is not to say that possible combinations of these two types may

not exist as well. Grinshpon's exegesis would be more realistic if it did not insist on

such an extreme polarity between the yogin/yoginT with his or her "aberrantbehavior"

and others with their "well-adjusted perceptions" (p. 1).

LOLA WILLIAMSON

Universityof Wisconsin-Madison

Water in Nepal. By DIPAK GYAWALI. Lalitpur: Himal Books and Panos

South Asia, with Nepal Water Conservation Foundation, 2001. xiv, 280 pp.

$25.00 (cloth).

This content downloaded from 151.100.161.185 on Thu, 16 Oct 2014 05:29:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Process Model of Action-Intuition and Direct-Referent ( - Murasati - )Document9 paginiProcess Model of Action-Intuition and Direct-Referent ( - Murasati - )Fredrik Markgren100% (1)

- Ends and Means HR Approaches To Armed Groups ADocument90 paginiEnds and Means HR Approaches To Armed Groups AHichamRaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boyer, Functional Origins of Religious Concepts - Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds (Articolo)Document21 paginiBoyer, Functional Origins of Religious Concepts - Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds (Articolo)Viandante852Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Social PhenomenonDocument12 paginiUnderstanding Social Phenomenonmd ishtiyaque alamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hrdy, Sarah. Mother Nature, Ch. 8 Unimaginable VariationDocument10 paginiHrdy, Sarah. Mother Nature, Ch. 8 Unimaginable VariationChristopher TaylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Cup of Tea With VimalaDocument4 paginiA Cup of Tea With VimalaJuan OlanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New Approach To The Hard Problem of Consciousness: A Quasicrystalline Language of "Primitive Units of Consciousness" in Quantized SpacetimeDocument26 paginiA New Approach To The Hard Problem of Consciousness: A Quasicrystalline Language of "Primitive Units of Consciousness" in Quantized SpacetimeStephanie Nadanarajah100% (1)

- Cap 1 - The - Social - Psychology - of - PowerDocument27 paginiCap 1 - The - Social - Psychology - of - PowercaosdeayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit - 13 - JIDDU KRISHNAMURTI FREEDOMDocument13 paginiUnit - 13 - JIDDU KRISHNAMURTI FREEDOMheretostudyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jong2013 Collective Trauma ProcessingDocument18 paginiJong2013 Collective Trauma ProcessingLuana SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Called ThinkingDocument67 paginiWhat Is Called ThinkingjrewingheroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vimala Thakar - Awakening To Total Revolution - Enlightenment and The World CrisisDocument9 paginiVimala Thakar - Awakening To Total Revolution - Enlightenment and The World CrisisbfranckÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henk Oosterling Avoiding Nihilism by Affirming Nothing Hegel On Buddhism PDFDocument27 paginiHenk Oosterling Avoiding Nihilism by Affirming Nothing Hegel On Buddhism PDFJacqueCheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: The Definitive Guide to Awaken Your Hidden Potential and Purify Your Spirit – Extended EditionDe la EverandYoga Sutras of Patanjali: The Definitive Guide to Awaken Your Hidden Potential and Purify Your Spirit – Extended EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Contemporary World Issues) Clifford J. Sherry-Animal Rights - A Reference handbook-ABC-CLIO (2009) PDFDocument325 pagini(Contemporary World Issues) Clifford J. Sherry-Animal Rights - A Reference handbook-ABC-CLIO (2009) PDFRPÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dharmasastra and Modern LawDocument25 paginiThe Dharmasastra and Modern Lawsunil sondhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rational Believer: Choices and Decisions in the Madrasas of PakistanDe la EverandThe Rational Believer: Choices and Decisions in the Madrasas of PakistanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theology and SociologyDocument5 paginiTheology and SociologyVictor Breno Farias BarrozoÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Study For SuccessDocument119 paginiHow To Study For Successpanganaipardon2Încă nu există evaluări

- EssentialSantMat PDFDocument49 paginiEssentialSantMat PDFstrgates34Încă nu există evaluări

- Local Wisdom Teaching in Serat Sastra GendhingDocument11 paginiLocal Wisdom Teaching in Serat Sastra GendhingNanang NurcholisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dialectical Writing 1982Document8 paginiDialectical Writing 1982palzipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lachman - From Metaphysics To Art and Back (Sobre Suzanne K Langer)Document21 paginiLachman - From Metaphysics To Art and Back (Sobre Suzanne K Langer)Elliott SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- All Life Is Yoga: Constant Remembrance of the MotherDe la EverandAll Life Is Yoga: Constant Remembrance of the MotherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feminist Jurisprudence - Why Law Must Consider Womens PerspectiveDocument4 paginiFeminist Jurisprudence - Why Law Must Consider Womens PerspectivesmartjerkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foucault and FeminismDocument17 paginiFoucault and FeminismPedro Ribeiro da Silva100% (1)

- Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Dao: Ancient Chinese Thought in Modern American LifeDe la EverandLife, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Dao: Ancient Chinese Thought in Modern American LifeEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Introductory Concepts in Sociology: Compiled by Anacoreta P. Arciaga Faculty Member-Social Sciences DepartmentDocument21 paginiIntroductory Concepts in Sociology: Compiled by Anacoreta P. Arciaga Faculty Member-Social Sciences DepartmentPalos DoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12 1 PDFDocument6 pagini12 1 PDFdronregmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ue Philosophy BookDocument103 paginiUe Philosophy BookTitus Inkailwila WalambaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peace Quotes Updated/revised 10/9/2013Document121 paginiPeace Quotes Updated/revised 10/9/2013Steve FryburgÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Peace Psychology Book Series 25) Stella Sacipa-Rodriguez, Maritza Montero (Eds.) - Psychosocial Approaches To Peace-Building in Colombia-Springer International Publishing (2014)Document166 pagini(Peace Psychology Book Series 25) Stella Sacipa-Rodriguez, Maritza Montero (Eds.) - Psychosocial Approaches To Peace-Building in Colombia-Springer International Publishing (2014)Alex AgrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Systems and Emergence, Rationality and Imprecision, Free-Wheeling and Evidence, Science and Ideology. Social Science and Its Philosophy According To Van Den Berg. Mario BungeDocument20 paginiSystems and Emergence, Rationality and Imprecision, Free-Wheeling and Evidence, Science and Ideology. Social Science and Its Philosophy According To Van Den Berg. Mario BungeOctavio ChonÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Dimensions of Asian Spirituality) Doris R. Jakobsh - Sikhism-University of Hawai'i Press (2012)Document161 pagini(Dimensions of Asian Spirituality) Doris R. Jakobsh - Sikhism-University of Hawai'i Press (2012)Tatuka DolidzeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edited Volume Buddhist and Islamic OrderDocument233 paginiEdited Volume Buddhist and Islamic OrdergygyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prefigurative Politics and Anthropological Methodologies - Niki ThorneDocument7 paginiPrefigurative Politics and Anthropological Methodologies - Niki Thorneyorku_anthro_confÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Qualifies A Student For VedantaDocument6 paginiWhat Qualifies A Student For VedantaKoontee mohabeerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zen Christian ExperienceDocument7 paginiZen Christian ExperienceazrncicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atma Bodha: by Adi SankaracharyaDocument4 paginiAtma Bodha: by Adi SankaracharyaJadenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Panarchy HollingDocument16 paginiPanarchy HollingMaria Clara Betancur CastrillonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Core of Yoga: EnglishDocument39 paginiCore of Yoga: EnglishVivekananda KendraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 What Is PhilosophyDocument8 paginiLecture 1 What Is PhilosophyhellokittysaranghaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defining "Religion"Document19 paginiDefining "Religion"fwoobyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jean-Hampton - Political Phylosophie PDFDocument25 paginiJean-Hampton - Political Phylosophie PDFalvarito_alejandroÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ludulogue ManualDocument58 paginiThe Ludulogue Manualanon_435053143100% (1)

- The Functionalist Perspective On Education - ReviseSociologyDocument7 paginiThe Functionalist Perspective On Education - ReviseSociologyMohammad YounusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michel Foucault and ZenDocument3 paginiMichel Foucault and ZenarquipelagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- LBB JivanmuktiDocument22 paginiLBB JivanmuktiFranck Bernede100% (1)

- The Fallacy of CompositionDocument11 paginiThe Fallacy of CompositionEmier ZulhilmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- PatanjaliYogaSutraSwamiVivekanandaSanEng PDFDocument143 paginiPatanjaliYogaSutraSwamiVivekanandaSanEng PDFDeepak Rana100% (1)

- PanarchyDocument12 paginiPanarchyRominaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 852-Article Text-1222-1-10-20140703 PDFDocument7 pagini852-Article Text-1222-1-10-20140703 PDFArtur Ricardo De Aguiar WeidmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Methodologies in Peace Psychology - Peace Research by Peaceful MeansDocument464 paginiMethodologies in Peace Psychology - Peace Research by Peaceful MeansJaved100% (1)

- Decolonizing YogaDocument9 paginiDecolonizing YogaChristina GrammatikopoulouÎncă nu există evaluări

- BARRIA Global Manifesto 2024Document317 paginiBARRIA Global Manifesto 2024Annie PedretÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddhism and Physics Interdependence From Classical Causality To Quantum Entanglement Michel BitbolDocument15 paginiBuddhism and Physics Interdependence From Classical Causality To Quantum Entanglement Michel BitbolsaironweÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mālatīmādhava Ed. Coulson 1989Document343 paginiMālatīmādhava Ed. Coulson 1989Cecco Angiolieri100% (1)

- Pātañjalabhāṣyavārttika by VijñānabhikṣuDocument139 paginiPātañjalabhāṣyavārttika by VijñānabhikṣuCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pūrva Mīmā Sā From An Interdisciplinary Point of View - Pandurangi, K.T PDFDocument685 paginiPūrva Mīmā Sā From An Interdisciplinary Point of View - Pandurangi, K.T PDFCecco Angiolieri100% (1)

- Śār Gadharapaddhati 2Document5 paginiŚār Gadharapaddhati 2Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- KumbhakapaddhatiDocument11 paginiKumbhakapaddhatiCecco Angiolieri0% (1)

- Sarvadarśanasa Graha (Pātañjaladarśanam)Document12 paginiSarvadarśanasa Graha (Pātañjaladarśanam)Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anil Chandra Banerjee - Lectures On Rajput History (1962, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay) - Libgen - LiDocument204 paginiAnil Chandra Banerjee - Lectures On Rajput History (1962, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay) - Libgen - LiCecco Angiolieri100% (1)

- Prakaranapancika Benares FullDocument317 paginiPrakaranapancika Benares FullCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- George Garzone Concept Worksheet1Document7 paginiGeorge Garzone Concept Worksheet1crissol67100% (6)

- Songbook Pixinguinha PDFDocument124 paginiSongbook Pixinguinha PDFRoger Menezes100% (8)

- Cycles and Coltrane Changes Giant StepsDocument12 paginiCycles and Coltrane Changes Giant Stepsprocopio99Încă nu există evaluări

- Charlie Parker Tune Book PDFDocument84 paginiCharlie Parker Tune Book PDFFranklin Y. Guerrero100% (3)

- Chord-Scale Theory: II 7 (?9) Imi7Document2 paginiChord-Scale Theory: II 7 (?9) Imi7Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mīmā Sā Ślokavārttika and Kāśika I, II - Sambasiva, K.Document544 paginiMīmā Sā Ślokavārttika and Kāśika I, II - Sambasiva, K.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remarks On The Kāvyamāla-Edition of Jayadratha Haracaritacintamā I, Tsuchida, R. (1997)Document11 paginiRemarks On The Kāvyamāla-Edition of Jayadratha Haracaritacintamā I, Tsuchida, R. (1997)Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mīmā Sā Ślokavārttika and Kāśika III - Sombasiva, K.Document210 paginiMīmā Sā Ślokavārttika and Kāśika III - Sombasiva, K.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Essays On Pūrva Mīmā Sā - Pandurangi K.T.Document316 paginiCritical Essays On Pūrva Mīmā Sā - Pandurangi K.T.Cecco Angiolieri100% (1)

- B Hati of Prabhākara - Madras Edition pt1Document213 paginiB Hati of Prabhākara - Madras Edition pt1Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient India and South India History and Culture Vol II - Ayiangar, S.Document890 paginiAncient India and South India History and Culture Vol II - Ayiangar, S.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mīmā Sā Philosophy of Langauge - Jha, U.Document104 paginiMīmā Sā Philosophy of Langauge - Jha, U.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophy Volume 16 Philosophy of Pūrva Mīmā SāDocument341 paginiEncyclopedia of Indian Philosophy Volume 16 Philosophy of Pūrva Mīmā SāCecco Angiolieri83% (6)

- The Epigrams Attributed To Bhart Hari - Kosambi, D.D.Document349 paginiThe Epigrams Attributed To Bhart Hari - Kosambi, D.D.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- From The Panchatantra To La Fontaine: Migrations of Didactic Animal Illustration From India To The West - Simona Cohen and Housni Alkhateeb ShehadaDocument64 paginiFrom The Panchatantra To La Fontaine: Migrations of Didactic Animal Illustration From India To The West - Simona Cohen and Housni Alkhateeb ShehadaCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient India and South Indian History and Culture Vol I - Aiyangar, S.Document864 paginiAncient India and South Indian History and Culture Vol I - Aiyangar, S.Cecco Angiolieri100% (1)

- Bhart Hari On Spho A and Universals - Bronkhorst, J.Document17 paginiBhart Hari On Spho A and Universals - Bronkhorst, J.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Meaning in The Indian Philosophy of Language - Varma, S.Document15 paginiAnalysis of Meaning in The Indian Philosophy of Language - Varma, S.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To The Theory of Spho A - Bhattacharya, G.Document5 paginiIntroduction To The Theory of Spho A - Bhattacharya, G.Cecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moag 2002 PDFDocument557 paginiMoag 2002 PDFCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Theory of Propositions - Smith, N.J.J PDFDocument43 paginiA Theory of Propositions - Smith, N.J.J PDFCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study in The Dialectics of Spho A - Bhattacharya, G. N PDFDocument122 paginiA Study in The Dialectics of Spho A - Bhattacharya, G. N PDFCecco AngiolieriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Quotation EIA Study Mumbai MetroDocument12 paginiSocial Quotation EIA Study Mumbai MetroAyushi AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- School Form 10 SF10 Learner Permanent Academic Record JHS Data Elements DescriptionDocument3 paginiSchool Form 10 SF10 Learner Permanent Academic Record JHS Data Elements DescriptionJun Rey LincunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sermon Notes: "True Greatness" (Luke 9:46-50)Document3 paginiSermon Notes: "True Greatness" (Luke 9:46-50)NewCityChurchCalgary100% (1)

- Republic V Tanyag-San JoseDocument14 paginiRepublic V Tanyag-San Joseyannie11Încă nu există evaluări

- Dream Job RequirementsDocument4 paginiDream Job RequirementsOmar AbdulAzizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wohnt Der Teufel in Haus 2 ? Amigo Affäre V Sicherheeeit ! Der Mecksit Vor Gericht Und Auf Hoher See..Document30 paginiWohnt Der Teufel in Haus 2 ? Amigo Affäre V Sicherheeeit ! Der Mecksit Vor Gericht Und Auf Hoher See..Simon Graf von BrühlÎncă nu există evaluări

- District MeetDocument2 paginiDistrict MeetAllan Ragen WadiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Rajasthan Admit CardDocument2 paginiUniversity of Rajasthan Admit CardKishan SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental ProfessionalsDocument8 paginiEndodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental Professionalsbobs_fisioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bilingual TRF 1771 PDFDocument18 paginiBilingual TRF 1771 PDFviviÎncă nu există evaluări

- BUBBIO, Paolo. - Hegel, Heidegger, and The IDocument19 paginiBUBBIO, Paolo. - Hegel, Heidegger, and The I0 01Încă nu există evaluări

- Ucsp Week 7Document10 paginiUcsp Week 7EikaSoriano100% (1)

- Crim Set1 Case18.19.20Document6 paginiCrim Set1 Case18.19.20leo.rosarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laffitte 2nd Retrial Motion DeniedDocument6 paginiLaffitte 2nd Retrial Motion DeniedJoseph Erickson100% (1)

- Unit 10 Observation Method: StructureDocument14 paginiUnit 10 Observation Method: StructuregeofetcherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internet Marketing Ch.3Document20 paginiInternet Marketing Ch.3Hafiz RashidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 Summary: Cultural Influence On Consumer BehaviourDocument1 paginăChapter 11 Summary: Cultural Influence On Consumer BehaviourdebojyotiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Đề thi thử no.14 GDDT NAM DINH 2018-2019Document4 paginiĐề thi thử no.14 GDDT NAM DINH 2018-2019Dao Minh ChauÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Macabre Motifs in MacbethDocument4 paginiThe Macabre Motifs in MacbethJIA QIAOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estimating Land ValuesDocument30 paginiEstimating Land ValuesMa Cecile Candida Yabao-Rueda100% (1)

- (ThichTiengAnh - Com) 100 Cau Dong Nghia - Trai Nghia (HOANG XUAN Hocmai - VN) - Part 3 KEY PDFDocument19 pagini(ThichTiengAnh - Com) 100 Cau Dong Nghia - Trai Nghia (HOANG XUAN Hocmai - VN) - Part 3 KEY PDFTrinh Trần DiệuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Determinants of Formal and Informal Sector Employment in The Urban Areas of Turkey (#276083) - 257277Document15 paginiDeterminants of Formal and Informal Sector Employment in The Urban Areas of Turkey (#276083) - 257277Irfan KurniawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Urbanization of An Idea Imagining Nature Through Urban Growth Boundary Policy in Portland OregonDocument28 paginiThe Urbanization of An Idea Imagining Nature Through Urban Growth Boundary Policy in Portland OregoninaonlineordersÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Purple JarDocument4 paginiThe Purple JarAndrada Matei0% (1)

- Sales Agency and Credit Transactions 1Document144 paginiSales Agency and Credit Transactions 1Shaneen AdorableÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homework 4題目Document2 paginiHomework 4題目劉百祥Încă nu există evaluări

- Helena Monolouge From A Midsummer Night's DreamDocument2 paginiHelena Monolouge From A Midsummer Night's DreamKayla Grimm100% (1)

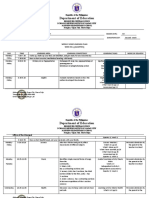

- Workweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Document15 paginiWorkweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Lenna Paguio100% (1)

- Data-Modelling-Exam by NaikDocument20 paginiData-Modelling-Exam by NaikManjunatha Sai UppuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abm 12 Marketing q1 Clas2 Relationship Marketing v1 - Rhea Ann NavillaDocument13 paginiAbm 12 Marketing q1 Clas2 Relationship Marketing v1 - Rhea Ann NavillaKim Yessamin MadarcosÎncă nu există evaluări